“Ha-ha-ha-HA-ha! Ha-ha-ha-HA-ha! That’s the Woody Woodpecker Song…”

In 1947, musicians George Tibbles and Ramey Idriss played Walter Lantz their new song about his famous manic woodpecker over the phone. Tibbles and Idriss wanted it published, and Lantz agreed. In October of that year, James Caesar Petrillo, union leader and head of the American Federation of Musicians, outraged that jukebox companies and disc jockeys made more money than the musicians in his union, announced a nationwide strike by all musicians in the country. It would be effective at the stroke of midnight, January 1st, 1948. This gave the record companies three months to stockpile recorded songs. Petrillo had paralyzed the record industry with a prior ban that lasted from August 1942 to late 1944.

In 1947, musicians George Tibbles and Ramey Idriss played Walter Lantz their new song about his famous manic woodpecker over the phone. Tibbles and Idriss wanted it published, and Lantz agreed. In October of that year, James Caesar Petrillo, union leader and head of the American Federation of Musicians, outraged that jukebox companies and disc jockeys made more money than the musicians in his union, announced a nationwide strike by all musicians in the country. It would be effective at the stroke of midnight, January 1st, 1948. This gave the record companies three months to stockpile recorded songs. Petrillo had paralyzed the record industry with a prior ban that lasted from August 1942 to late 1944.

On New Year’s Eve, Tibbles and Idriss approached popular bandleader Kay Kyser, in the midst of an immense recording session, and wanted their Woody Woodpecker song recorded before midnight. Kyser agreed, but his other songs would need recording first. At ten minutes to midnight, Kyser recorded the song. Gloria Wood sang the lyrics and Harry Babbitt performed the woodpecker’s trademark laugh. While the strike ended only a few weeks later, The Woody Woodpecker Song became a magnificent hit in June 1948, selling over 250,000 records within ten days, with 155,000 sales of sheet music.

Lantz stated to The San Diego Daily Journal (June 29, 1948) that Woody’s laugh hadn’t been imitated so incessantly before the public’s exposure to the song. He heard it everywhere – at the market, the drug store, in telephone calls, and at the barbershop. It even decreased his golf scores, but he couldn’t argue with its popularity. To ensure further success, he rushed the song to the soundtrack of Dick Lundy’s Wet Blanket Policy.

Lundy was part of a new group of animators that emerged at Disney’s in 1929. He started as an in-betweener and cel washer and became assistant to esteemed animator Norm Ferguson. As a full animator, Lundy was adept at dancing sequences (i.e. Piper and Fiddler Pig in Three Little Pigs and Mickey’s Astaire number in Thru the Mirror) but his animation of Donald Duck for the character’s second appearance, Orphan’s Benefit, proved he was just as competent with personality animation. It was Lundy who developed Donald’s belligerent tantrums, as he hopped around with one arm stretched out.

Lundy was part of a new group of animators that emerged at Disney’s in 1929. He started as an in-betweener and cel washer and became assistant to esteemed animator Norm Ferguson. As a full animator, Lundy was adept at dancing sequences (i.e. Piper and Fiddler Pig in Three Little Pigs and Mickey’s Astaire number in Thru the Mirror) but his animation of Donald Duck for the character’s second appearance, Orphan’s Benefit, proved he was just as competent with personality animation. It was Lundy who developed Donald’s belligerent tantrums, as he hopped around with one arm stretched out.

When Lundy was promoted to director, he mainly made Donald Duck cartoons, along with Navy training films during World War II. Around October 1943, Lundy found himself without any animator/directorial assignments, even after coming up to Disney’s office to discuss his status. He was terminated and felt betrayed, since he helped organize the burgeoning studio. To make matters worse, he hadn’t received a bonus for his work on Snow White when it finished. He migrated to the Lantz studio the following month.

As he arrived at the studio, Lundy animated on Culhane’s Lantz cartoons until he started directing on March 23, 1944. Culhane and Lundy’s cartoons at Lantz are night and day, particularly when it comes to story and characterization. Culhane was often able to improve writer Ben Hardaway’s meager contributions, but Lundy was not as conscientious. Woody Woodpecker is relegated to a “fall guy” figure, in the Jack Hannah Donald Duck vein, in Lundy’s cartoons. The Coo-Coo Bird, Solid Ivory and The Mad Hatter are big examples of this, but Lundy’s efforts were more helpful in other aspects.

Culhane’s departure in October 1945 left Lundy as the sole director. He brought a new visual flair to the Lantz cartoons. The rough-and-tumble, formally innovative cartoons of his predecessor were now smoothed down to a slick, graceful quality. Other changes proceeded under Lundy’s watch. The Swing Symphonies were now replaced with the short-lived “Musical Miniatures” (The Poet and Peasant, Musical Moments from Chopin, The Overture to William Tell, The Bandmaster, Kiddie Concert and Pixie Panic), profiling classical melodies as well as Lundy’s brilliant musical timing. Adjustments aside, Lantz was not keen on Lundy’s Disney influence, knowing he didn’t share Culhane’s quick humor. As well, his shorts cost more to make, due to their more elaborate animation. The Musical Miniatures were Lantz’s most expensive series, costing over $30,000 to produce. After a dispute with Universal, Lantz signed a distribution contract with United Artists on February 12, 1947.

Culhane’s departure in October 1945 left Lundy as the sole director. He brought a new visual flair to the Lantz cartoons. The rough-and-tumble, formally innovative cartoons of his predecessor were now smoothed down to a slick, graceful quality. Other changes proceeded under Lundy’s watch. The Swing Symphonies were now replaced with the short-lived “Musical Miniatures” (The Poet and Peasant, Musical Moments from Chopin, The Overture to William Tell, The Bandmaster, Kiddie Concert and Pixie Panic), profiling classical melodies as well as Lundy’s brilliant musical timing. Adjustments aside, Lantz was not keen on Lundy’s Disney influence, knowing he didn’t share Culhane’s quick humor. As well, his shorts cost more to make, due to their more elaborate animation. The Musical Miniatures were Lantz’s most expensive series, costing over $30,000 to produce. After a dispute with Universal, Lantz signed a distribution contract with United Artists on February 12, 1947.

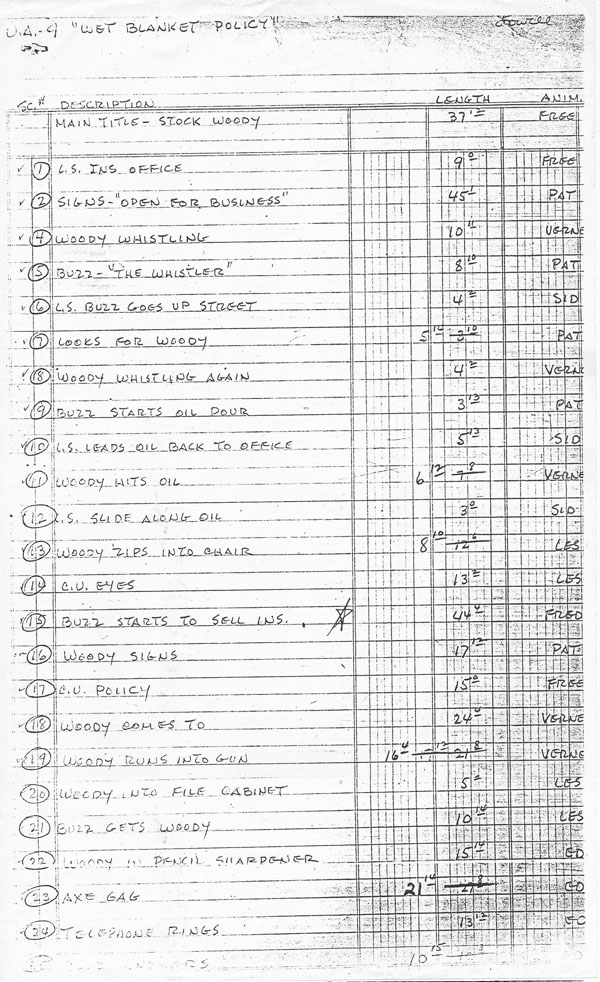

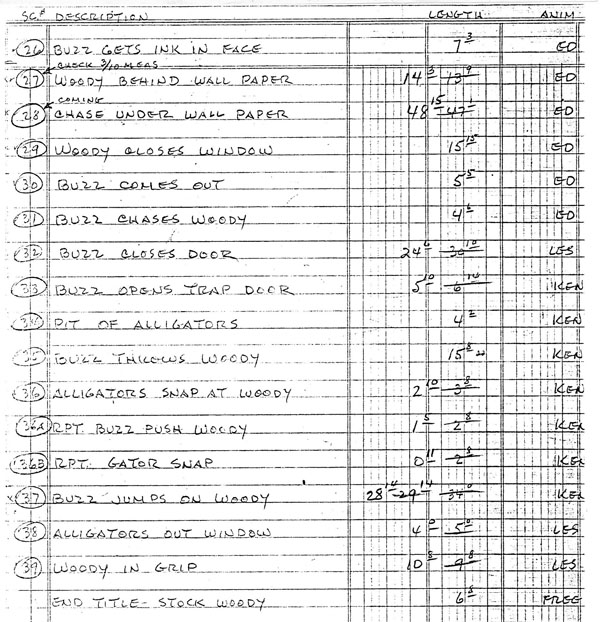

Wet Blanket Policy (released August 27th, 1948) not only boosted The Woody Woodpecker Song to an Academy Award nomination (the only animated short with this distinction), but introduced Buzz Buzzard, a stronger adversary for Woody. Lionel Stander’s gravelly voice for Buzz provided the perfect mixture for animated villainy. Due to the afterthought of adding the song, the music doesn’t match with the first minute and half of the cartoon, and it obscures Buzz’s first line of dialogue (his first audible line “The Whistler!” is a reference to the 1940s radio mystery drama/film adaptation of the same name). The character/plot is a reprise of Dick Lundy’s last Donald cartoon, Flying Jalopy, where both main characters sign off crooked life insurance policies, and escape murder as soon as the ink is dry.

Ed Love and Fred Moore’s presence added to the visual sheen of Lundy’s cartoons. The alcoholic Moore had been fired from Disney’s in August 1946. He at first freelanced at Lantz, but was later on staff. Moore was given the opportunity to redesign Woody into a sleeker character. His only credit in the draft ─ of Buzz shilling his phony insurance ─ has great posing and flexibility. Ed Love has almost two minutes of animation in the cartoon, still carrying his sharp timing/drawing from Avery’s MGM cartoons. Pat Matthews also does some phenomenal work here, especially Buzz’s reaction to Woody’s nearby whistling.

Lantz’s cartoons were at the pinnacle of 1940s animation, but their producer was stricken with financial troubles with the Bank of America and distribution difficulties with UA. Lantz was forced lay off his artists. Each department grew empty by the week, with one last cartoon on the pipeline, Drooler’s Delight. Solely animated by Ed Love, it was Lundy’s last cartoon for the studio (it was also the last entry where Lionel Stander voiced Buzz Buzzard). Lundy’s polish and Stander’s voice vanished in one fell swoop when the studio closed (Stander had been blacklisted from films by the HUAC.) The studio re-opened a year later, but the slashed budgets guaranteed less vibrant animation, and Buzz was replaced by Dal McKennon, a talented voice actor that played him as more of a buffoon than a lout, as Stander had.

Here’s this week’s breakdown video (and keep your eyes peeled, there’s an ad for Lantz’s New Funnies comics somewhere!)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Thanks Devon, there is some great information here. I had a Castle Films 8mm print of this and i always laughed at the wallpaper chase. Keep up the great writing.

A historical aside re: The Woody Woodpecker Song. The other two hit versions of it were by Mel Blanc and the Sportsmen (Capitol), and Danny Kaye and the Andrews Sisters (Decca). Neither used union musicians: Mel Blanc and the Sportsmen were accompanied by a ukulele and ocarina, while Danny Kaye and the Andrews Sisters got a harmonica band. Ukuleles, ocarinas, harmonicas and kazoos were the major categories of instruments that weren’t represented by the AFofM at the time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJp7m7amMrU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9k4wo4Jzf8

Mel Blanc’s version sounds a lot like Gracie Lantz’s earliest Woody voice.

As good as the song itself was, for me – as already stated – it really threw off the timing for the first few scenes of this short. Had Lantz more time or money to produce a proper cartoon centred on / around the song, then it might have been different.

But thank you for revealing the one mystery that has been bugging me for years: what Buzz’s first words would have been in his debut. All I could ever make out via lip-sync was; “Open for business – mine! Confidentially (?) “. ‘The Whistler’ line helped to fill the gap after so long =)

While the strike ended only a few weeks later

Minor point, but the 1948 musician’s strike lasted nearly a year, not ending until December 14, 1948.

One person not amused by “The Woody Woodpecker Song,” despite recording it for Capitol, was Mel Blanc, who sued Leeds Music (the song’s publisher) and Walter Lantz for $250,000, arguing that the use of his Woody Woodpecker laugh was unauthorized and a violation of copyright laws. Blanc lost, the judge ruling that Blanc had never copyrighted the laugh, and so was not afforded any common law rights or protection. If Blanc had copyrighted the laugh before performing it on film for Lantz, it would have been his, but once the first film containing the Woody laugh had been released, it became Lantz’s property and Blanc no longer had any rights to it.

When Harry Babbitt died around ten years ago, a lot of confused obituaries reported (without qualification) that he was the guy who did Woody Woodpecker’s laugh. To my great annoyance.

“Mr. Duck Gets His Wings” was an odd duck among the Ducks. By this time, it seems that Disney’s main stars were unshakably identified as human (Goofy) or animal (Pluto) outside of the occasional random gag (Donald reacting to a duck recipe in a magazine; Horace catching himself whinnying). The Silly Symphonies could still offer farmyard societies and insect nightclubs, but the Disney stars took a pretty strict line on species identity. Ben Buzzard, with a foot (or talon) in both human and animal worlds (he can fly; Donald can’t), was a very rare bird in a non-Silly Symphony.

He’d be a common enough type at other studios. Woody, Bugs and Daffy could be either woodland creatures or urban humans; Sylvester and Tom could be housecats or homeowners. Mighty Mouse had to deal with cats who looked on mouse heroines as both appetizers and objects of lust. But at Disney, a dog in a suit was 100% human and a naked dog was 100% dog (even in “Man’s Best Friend”, where Goofy acquires a black dog who looks disturbingly like a nake Pete).

I think a better terminology would be sentient (Goofy, Donald) and non-sentient (Pluto), if you had to go there. It is something I’m sure many had in their minds while watching, but really, we shouldn’t be thinking that hard about it.

I think it was Wil Wheaton’s character in “Stand by Me” that posed the question of “if Pluto is a dog, what is Goofy?”

Devon, in the list of “Musical Miniatures” you mention “Pixie Panic”. Shouldn’t that be “Pixie PICNIC”? Perhaps you

got it confused with “Pantry Panic”.

The framing device of an insurance policy is similar to “The Flying Jalopy”, but most of the action is much more generic… Buzz may as well be hungry for roast woodpecker! 🙂

The hastily-inserted song over the opening scenes also makes it difficult to read the writing on Buzz’s office window.