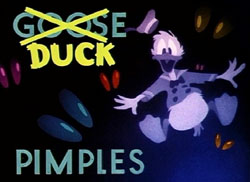

I have been anxious to write about this title since the launch of this series on Cartoon Research and now, in the spirit of the spooky Halloween season, it’s finally here!

I have been anxious to write about this title since the launch of this series on Cartoon Research and now, in the spirit of the spooky Halloween season, it’s finally here!

During the 1940s, the Second World War caused a profound apprehension in American society—a bleak perspective that seeped into popular media—cinema, suspense radio programs and pulp literature. Three different radio programs dominated the airwaves, inciting these fears in intrigued listeners, Inner Sanctum Mystery which debuted in 1941, and Suspense, originating as a solo episode a year earlier but aired regularly from 1942. That same year, the growing trend in thriller radio programs launched a revival of Lights Out, a program first aired in 1934 but cancelled five years later.

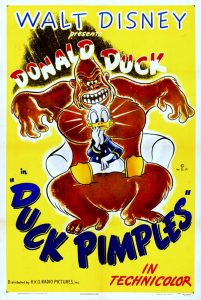

The subgenre of gangster movies in live-action Hollywood films evolved into a proliferation of crime dramas characterized by a bitter cynicism and stark chiaroscuro lighting, later called film noir. The horror genre also thrived with Disney’s distributor RKO Radio Pictures’ string of psychological thrillers, under the supervision of producer Val Lewton, presenting elements of atmospheric terror that differentiated from the monster films released by Universal.

The subgenre of gangster movies in live-action Hollywood films evolved into a proliferation of crime dramas characterized by a bitter cynicism and stark chiaroscuro lighting, later called film noir. The horror genre also thrived with Disney’s distributor RKO Radio Pictures’ string of psychological thrillers, under the supervision of producer Val Lewton, presenting elements of atmospheric terror that differentiated from the monster films released by Universal.

The peculiar narrative of Duck Pimples seems attributable to its two credited story men, Virgil “Vip” Partch and Dick Shaw. Shaw, a freelance cartoonist who wanted to get into the animation field, met Partch at a bar near the Burbank studio. Partch worked as an assistant animator in the early 1940s and wanted to pursue magazine cartooning, but hesitated to send his artwork to publishers. Shaw sent Partch’s sketches in secrecy to Gurney Williams, the humor editor of Collier’s, and they were accepted. In March 1941, Shaw received a job at the studio as an errand boy, but quickly rose through the ranks and became an in-betweener. Shortly after, his gag cartoons gained notice and he was shifted to the story department. Partch was laid off during the 1941 strike, but Shaw continued to work in the studio on double-duty as a story/gag-man on the theatrical productions and by the end of 1942, in Floyd Gotfreddson’s comic strip department on gag strips and continuities (as seen here.) However, the two cartoonists remained close friends—Shaw often invited Partch (and other Disney staffers) on his tugboat and at his home on Balboa Island.

Without clear and accessible records, it is hard to determine when the story of Duck Pimples was written and storyboarded. Like their features, many Disney shorts underwent sporadic gestation periods. Projects would be shelved then revived and rearranged. (For instance, Trombone Trouble, released February 1944, started as early as August 1941.) Showmen’s Trade Reviews reported Duck Pimples was in production, along with other Disney shorts in the pipeline, by June 3, 1944.

Without clear and accessible records, it is hard to determine when the story of Duck Pimples was written and storyboarded. Like their features, many Disney shorts underwent sporadic gestation periods. Projects would be shelved then revived and rearranged. (For instance, Trombone Trouble, released February 1944, started as early as August 1941.) Showmen’s Trade Reviews reported Duck Pimples was in production, along with other Disney shorts in the pipeline, by June 3, 1944.

As JB Kaufman and David Gerstein’s research has shown, Jack Kinney was originally slated to direct Donald’s Crime before it was reassigned to Jack King. In both pictures, Donald is immersed into foreboding territories, tormented by his own imagination; in Duck Pimples, he suffers such an otherworldly anguish in his own home! Excelling in fast action and comedy at Disney’s, Kinney’s sensibilities as a director were appropriate for this story. In addition to the influences harvested from thriller radio programs and film noir, the frenetic MGM cartoons directed by Tex Avery proved highly significant: Oliver Wallace’s music score accompanied by the Novachord—modeled after Inner Sanctum Mystery— has similarities to the organ music that accompanied Who Killed Who (1943), and the redheaded curvaceous dame bears a slight resemblance to Red Hot Riding Hood. (With the success of the “How-To” Goofy cartoons, Kinney was offered a job at MGM at a much higher salary in the mid-forties, and Disney offered a raise matching the same amount, so Kinney stayed.)

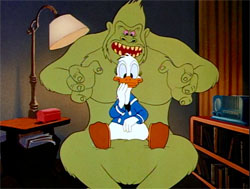

Hal King animates the opening scenes of Donald listening to a radio thriller, but a womanly scream startles him and he turns the dial to another station. However, each broadcast is more terrifying than the last. “Doodles” Weaver, a film/radio character actor who voiced in several Disney cartoons, doubles as the host that sets the mood for the evening and in a separate program, an elderly man’s last words before a watery demise. When Donald switches to a program involving an encounter with a killer ape—with radio actor Jack Mather shouting the warning—Donald’s chair transforms into the shape of a large gorilla, ready to grasp the frightened duck, before he shuts off the radio and zips away without noticing the menace behind him.

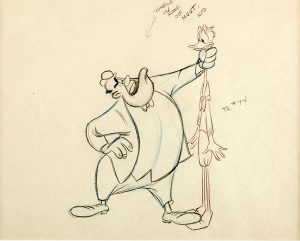

The angular drawing style seen in Virgil Partch’s later magazine cartoons is translated through the intimidating large figure (voiced by Jack Mather) wearing a raincoat, whose large frame nearly fills the doorway and ominously stares down at Donald. The contents inside his raincoat reveal the purpose of his visit—he is a traveling book salesman peddling subscriptions of pulp horror/mystery novels to win a bicycle. As animated by John Sibley, the salesman becomes a giddy child, pedaling an invisible bike in Donald’s living room. After a crash landing, his wares are strewn about the room and the salesman rides away with a bent wheel, vanishing in thin air.

The angular drawing style seen in Virgil Partch’s later magazine cartoons is translated through the intimidating large figure (voiced by Jack Mather) wearing a raincoat, whose large frame nearly fills the doorway and ominously stares down at Donald. The contents inside his raincoat reveal the purpose of his visit—he is a traveling book salesman peddling subscriptions of pulp horror/mystery novels to win a bicycle. As animated by John Sibley, the salesman becomes a giddy child, pedaling an invisible bike in Donald’s living room. After a crash landing, his wares are strewn about the room and the salesman rides away with a bent wheel, vanishing in thin air.

In the aftermath, Donald chooses a mystery novel detailing a case of stolen pearls. Unbeknownst to Donald, captivated by the whodunit novel, a pair of black hairy hands emerges from the book, nearly strangling him. In the original storyboards, more disturbing imagery appeared out of the book as the duck continues reading—Donald’s cuckoo clock has first a cuckoo pop out, then a shrieking woman who is then choked by the ape-like hands from within the clock behind her. As the tension mounts in the story, Donald’s living room changes to a darkly lit cityscape when a gangster known as Dopey Davis (Jack Mather) grabs the duck and begs to be free from the consequences of his crime. As one of the main animators that specialized on Donald Duck, Hal King usually gave his characters a wide emotional range; he animates Dopey Davis nervously twitching after hearing the sharp screech of a police car parked in place, and Donald’s nail-biting unease when the gangster is questioned by an accusatory voice (Billy Bletcher) inside the book.

Pointed out as the culprit, a plainclothes police detective is quick to accuse the duck of stealing the pearls. Donald’s room is converted into the realm of crime fiction, with warped backgrounds that represent incrimination for his theft— a courtroom stand and a police line-up appear when the detective stretches the duck’s body to its tallest height. Next, a shapely feminine arm ascends from the book in a snake-like motion belonging to the shapely woman who has lost her pearls. An uncredited Fred Moore animates the first scenes of the sultry dame slinking out of the book. Milt Kahl is credited for the remaining scenes of the “little woman” (voiced by Mary Lenihan) searching for her pearls, as she climbs inside the detective’s coat. Moore handles the scenes of the detective interrogating Donald before they both think she has been kidnapped. One of the scenes omitted during production involved a gag where the dame pops out of the detective’s jacket, wearing Groucho Marx’s trademark glasses and mustache!

Pointed out as the culprit, a plainclothes police detective is quick to accuse the duck of stealing the pearls. Donald’s room is converted into the realm of crime fiction, with warped backgrounds that represent incrimination for his theft— a courtroom stand and a police line-up appear when the detective stretches the duck’s body to its tallest height. Next, a shapely feminine arm ascends from the book in a snake-like motion belonging to the shapely woman who has lost her pearls. An uncredited Fred Moore animates the first scenes of the sultry dame slinking out of the book. Milt Kahl is credited for the remaining scenes of the “little woman” (voiced by Mary Lenihan) searching for her pearls, as she climbs inside the detective’s coat. Moore handles the scenes of the detective interrogating Donald before they both think she has been kidnapped. One of the scenes omitted during production involved a gag where the dame pops out of the detective’s jacket, wearing Groucho Marx’s trademark glasses and mustache!

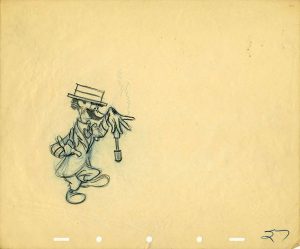

The dame now missing, the detective tries to get Donald to confess in an extended sequence animated by Milt Kahl. The detective calls to the motor-mouthed Leslie J. Clark (voiced by Harry Lang), another salesman character who specializes in hot irons. The character is a dual studio in-joke— a caricature of and named after animator Leslie James Clark, the first of the “Nine Old Men.” The interiors change from courtroom to torture chamber, with the gruesome instruments of punishment and execution displayed; a guillotine is seen while Donald races to dispose of the hot irons in his hands (credited to Al Bertino). The detective presses Donald again to return the young woman, and meanwhile, she continues her search by speaking with her friend Mabel over the telephone while inside his jacket. In Fred Moore’s animation of the girl, she is depicted as an absentminded ditz, accentuated by the usual softness of his draftsmanship. Compared to an earlier gag animated by Milt Kahl, she is drawn/animated as a more mature woman unaffected by the hot iron when she curls her hair.

The dame now missing, the detective tries to get Donald to confess in an extended sequence animated by Milt Kahl. The detective calls to the motor-mouthed Leslie J. Clark (voiced by Harry Lang), another salesman character who specializes in hot irons. The character is a dual studio in-joke— a caricature of and named after animator Leslie James Clark, the first of the “Nine Old Men.” The interiors change from courtroom to torture chamber, with the gruesome instruments of punishment and execution displayed; a guillotine is seen while Donald races to dispose of the hot irons in his hands (credited to Al Bertino). The detective presses Donald again to return the young woman, and meanwhile, she continues her search by speaking with her friend Mabel over the telephone while inside his jacket. In Fred Moore’s animation of the girl, she is depicted as an absentminded ditz, accentuated by the usual softness of his draftsmanship. Compared to an earlier gag animated by Milt Kahl, she is drawn/animated as a more mature woman unaffected by the hot iron when she curls her hair.

Marc Davis animates much of the denouement in the picture, with some scenes assigned to John Sibley. Wanted posters of the duck pinned on a corkboard and a padlocked jail cell surround the three characters as the action comes to a climax; Donald has a long, protruding switchblade pressed against his throat and the dame stands behind the detective brandishing a large axe, ready to strike.

Suddenly, the author of the novel J. Harold King (Jack Mather) steps out of the book to exonerate the duck. The name is a takeoff on James Patton King, otherwise known as Jack King, the principal director of the Donald Duck series during the 1940s.

The thief is revealed to be H. U. Hennessy, yet another studio in-joke named after layout artist Hugh Hennessy. (The original name given was Morgan, but was changed to Hennessy, in keeping with the trope of tough Irish policemen.) Sibley animates a small section where the thief is identified by name, and Davis takes over when Hennessy makes his escape, shooting Donald in the process with a toy gun. Sibley animates the final scenes of the film, starting with J. Harold King and the dame diving back into the book and Donald safe in his living room. He’s assured by a voice of conscience (Jack Mather) that the events stemmed from his imagination. Donald is left stupefied and convulsing by this notion as the missing pearls materialize around his neck at the iris out. The original ending had the gorilla from the start of the film slowly appearing out of the book, which Donald doesn’t notice.

The thief is revealed to be H. U. Hennessy, yet another studio in-joke named after layout artist Hugh Hennessy. (The original name given was Morgan, but was changed to Hennessy, in keeping with the trope of tough Irish policemen.) Sibley animates a small section where the thief is identified by name, and Davis takes over when Hennessy makes his escape, shooting Donald in the process with a toy gun. Sibley animates the final scenes of the film, starting with J. Harold King and the dame diving back into the book and Donald safe in his living room. He’s assured by a voice of conscience (Jack Mather) that the events stemmed from his imagination. Donald is left stupefied and convulsing by this notion as the missing pearls materialize around his neck at the iris out. The original ending had the gorilla from the start of the film slowly appearing out of the book, which Donald doesn’t notice.

In interviews about his career, animator Marc Davis mentioned an overall dissatisfaction with Duck Pimples. As he mentioned to historian Don Peri, “It was pretty bad…it was one of those tongue-in-cheek things. Walt was never tongue-in-cheek, and I think our own development didn’t permit it.” The film was released August 10th, 1945 — by that time, the two writers on the film “Vip” Partch and Dick Shaw were enlisted in military service, with Partch in the Army and Shaw in the Merchant Marines. Motion Picture Daily reported Duck Pimples was still running in theaters by March 11th, 1946, where it played at the State Lake Theater in Chicago, billed with Alfred Hitchcock’s psychoanalytical thriller Spellbound.

Enjoy the video and have a great October!

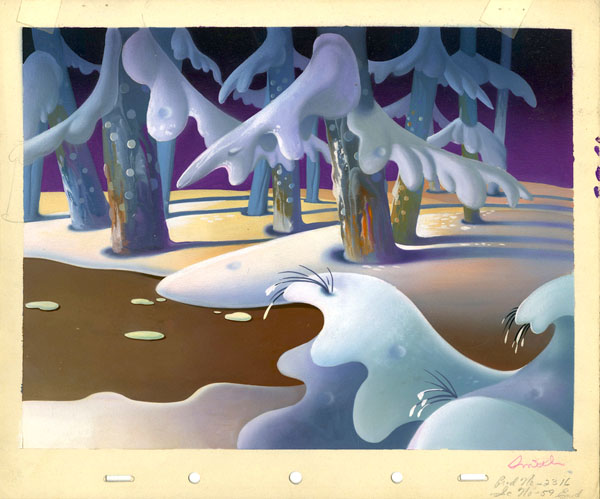

Production background for “Duck Pimples” by Nino Carbe

(Thanks to JB Kaufman, David Gerstein, Didier Ghez, Joe Campana, and Keith Scott for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Given the characters based on Hennessy, Clark and King, could “Dopey Davis” have been a caricature of Marc? If so, that might be another reason why he didn’t care for the cartoon.

Since Dopey Davis addresses Hennessy as “copper”, it seems as though Hennessy is a plainclothes police detective rather than a private eye. So “Duck Pimples” may be the first cartoon to show a policeman gobbling donuts!

The hardboiled detective genre in fiction came into its own in the 1920s, paralleling the rise of organised crime during Prohibition. Even H. L. Mencken published a pulp detective magazine, Black Mask, to subsidise his sophisticated literary journal The Smart Set, which had run at a loss since its founding. I’m not sure why the genre took so long to have an impact on film, but I suspect it has to do with the relaxing of some strictures of the Hollywood Code during the war. In these stories, as in “Duck Pimples”, police and other authority figures are typically portrayed as corrupt and/or incompetent; this was expressly forbidden by the Code.

And finally, the trope of the killer ape goes all the way back to the very first modern detective story, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”. Sorry, I guess maybe I should have said “Spoiler alert”….

Not only does the woman bear a resemblance to Avery’s Red Hot Riding Hood character, she also resembles the later character of Jessica from “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” Surely this was one of the inspirations.

There is an expanded version of this short embedded in “The Mad Hermit of Chimney Butte,” a compilation of Donald Duck cartoons made for the Disneyland/Walt Disney Presents TV show. A little bit of new animation is added showing the characters entering the book out of Donald’s sight before he opens the book and is tormented by these visions. Witch Hazel from the “Trick or Treat” film makes a return appearance as well. Walt Disney introduces and concludes the installment, in which the mysterious “Mad Hermit” is revealed to be none other than Donald himself.

The Nostalgia Critic does a very good take on this in his series DARK TOONS .. as the one and onl;y Doug Walker could do that.Even gives director Kinney a nod! Harry Lang did Donald voices….at WB, MGM, Lantz/Univ. and mopre..(he did a Donald like voice for an otherwise mute duckling in 1947’s WB short THE FOXY DUCKLING, if I;m right!)

Very “Tex” like Disney short, before ROGER RABBIT!

Doodles Weaver’s niece would end up co-starring in her own comedy/horror effort 40 years later, when Sigourney played the female lead in “Ghostbusters” (which had a little animation of the ghosts, monsters and Sta-Puft Marshmallow man….)

The attached video link is not working.

“Unable to play this video at this time. The number of allowed playbacks has been exceeded. Please try again later.”

Two interesting tidbits of trivia: 1) Jack Mather, and Harry Lang starred as the Cisco kid in a radio show of the same name (in the ’50’s) , and 2) Jack Hannah directed his first Donald Duck Short in the mid forties “Donald’s Off Day”.

Not to my surprise, John Sibley animated my favorite scene in this…. the finale with Donald doing that WTF?! take while the dame’s pearls materialize on his neck…. which always stayed with me ever since I first got into this short proving what an effect Sibley’s animation has always had on me.

But, seriously, all the animators on this are great. I mean any cartoon with Milt Kahl equals great animation and his animation of “the dame” and of Leslie J. Clark is more than solid stuff. And Hal King’s stuff was the animation that stayed with me the most after Sibley’s when I first “got into” this cartoon back in 1999; the Donald animation was what I really noticed and King was the “go-to” Donald guy for many years so he got a good chance to excel in this one. King and Sibley do a great job making Donald look really “crazed” in this cartoon.

J. Harold King might also be a reference to Hal King?

“Hmm. Sounds like ‘Inner Sanctum'” -Bugs Bunny

I had this one on VHS when I was young, so it’s among the first classic Disney shorts I ever saw. I certainly owe a lot of my long-running love of classic animation to repeat viewings of that tape. Those beautiful, eerie backgrounds stood out to me even then, especially that cavernous room that Donald runs through with the hot irons. One of Disney’s all-time best.

My favorite classic Disney cartoon

Leslie J. Kline might be a reference to Lantz animator Lester Kilne

An excellent overview of one of my absolute favorite Disney shorts–and yes, this is probably as close to Tex Avery as the studio ever got. I wish it were better known.

Hey Devon, I’m Aiden or @3GoldBalls on Twitter. I’m hosting a reanimated collab on both What’s Opera Doc and Big House Blues. Can you please show me a scene breakdown?

Big House Blues is The Pilot of Ren and Stimpy

No one mentions that the girl, while the under the coat, acts like a second pair of arms.