We’re back to animator breakdowns this month! This week, we follow little Ambrose in the Disney Silly Symphony, The Robber Kitten…

While many presume The Robber Kitten to be an original story born at Disney, the short is based on a 19th century children’s story purportedly authored by Robert Michael Ballantyne under the pseudonym “Comus.” In the original story, the unnamed kitten protagonist reveals his decision to become a thief in front of his mother before departing to find his intended victims. Upon his first outing as a criminal, the kitten beheads a rooster by gunshot, and then takes his body with him for dinner. Failing to rob a female cat of her purse—she has none—the kitten shoots at her and misses. After an initially chummy visit with an untrustworthy canine highwayman, who ends up turning on him in a violent assault, the kitten is implored by a friendly owl to surrender his nefarious plans and return home. Returning to his mother in tears, he decides to have his sword and pistol thrown into the fire as an act of reform.

The story outline for Disney’s version of The Robber Kitten circulated around the studio by September 1934. A surviving early script for the film, presumably by story director Bill Cottrell, indicates that the studio’s original name for the title character was Ferdinand. No doubt a more embarrassing name for the disgruntled young kitten, its use here predated the publication of Munro Leaf’s The Story of Ferdinand and the subsequent Disney film. Perhaps the original intended name was borrowed from one of the studio’s concept artists, Ferdinand Horvath. In the film, the kitten is named Ambrose but changes his name to “Butch” after his mother interrupts his highwayman play-acting by calling him down for his bath.

The story outline for Disney’s version of The Robber Kitten circulated around the studio by September 1934. A surviving early script for the film, presumably by story director Bill Cottrell, indicates that the studio’s original name for the title character was Ferdinand. No doubt a more embarrassing name for the disgruntled young kitten, its use here predated the publication of Munro Leaf’s The Story of Ferdinand and the subsequent Disney film. Perhaps the original intended name was borrowed from one of the studio’s concept artists, Ferdinand Horvath. In the film, the kitten is named Ambrose but changes his name to “Butch” after his mother interrupts his highwayman play-acting by calling him down for his bath.

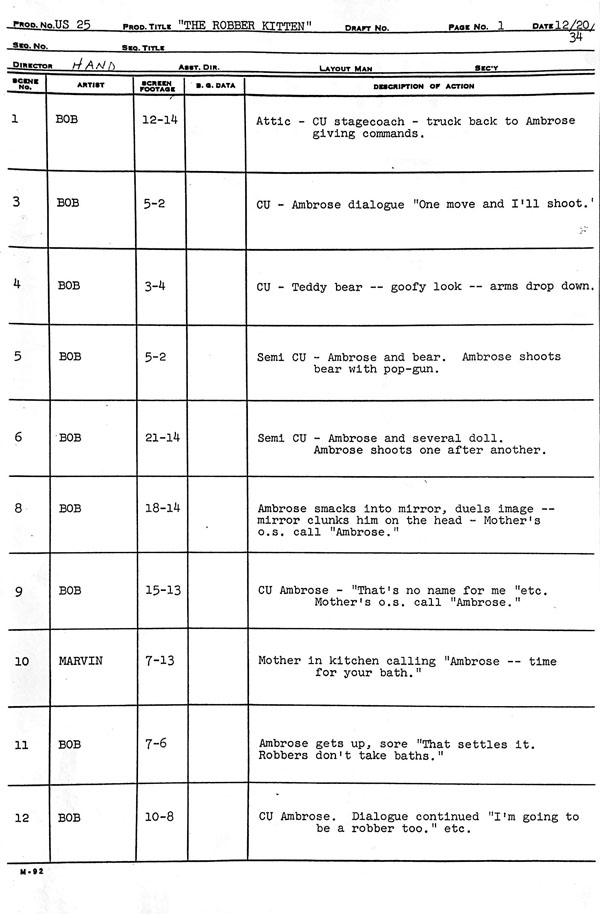

Animation on The Robber Kitten began in early October. As with several of director Dave Hand’s Silly Symphonies, a small number of animators contributed to the film, mainly cast by sequence. This film has five principal artists—Bob Wickersham, Hardie Gramatky, Marvin Woodward, Ham Luske and Bill Roberts.

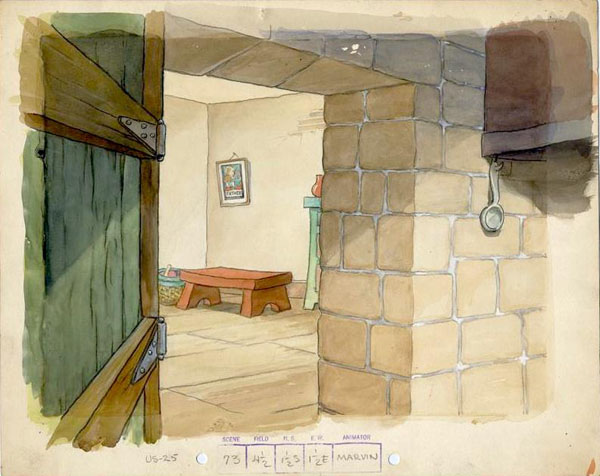

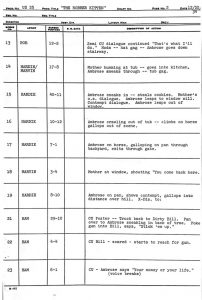

Wickersham animates the introductory sequences of Ambrose (voiced by Shirley Reed), from his playing stagecoach robber with his toys up until his determination to run away from home as he sneaks downstairs. Hardie Gramatky handles the sequence when Ambrose avoids his bath and pilfers a jar of cookies, pouring them into his satchel. After a boastful declaration (“No more baths for me!”), the novice thief makes his exit out the window but lands into a rain barrel full of water. Gramatky continues the sequence when Ambrose rides along on his hobbyhorse, but is called by his mother raising a brush. The stubborn kitten quickly brings his head up in defiance and turns away from her into the forest for adventure.

Wickersham animates the introductory sequences of Ambrose (voiced by Shirley Reed), from his playing stagecoach robber with his toys up until his determination to run away from home as he sneaks downstairs. Hardie Gramatky handles the sequence when Ambrose avoids his bath and pilfers a jar of cookies, pouring them into his satchel. After a boastful declaration (“No more baths for me!”), the novice thief makes his exit out the window but lands into a rain barrel full of water. Gramatky continues the sequence when Ambrose rides along on his hobbyhorse, but is called by his mother raising a brush. The stubborn kitten quickly brings his head up in defiance and turns away from her into the forest for adventure.

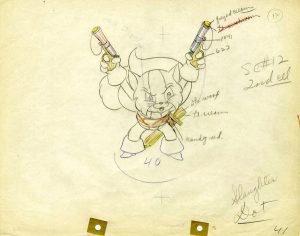

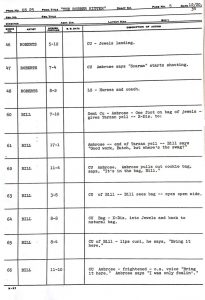

Ham Luske animates a large portion of The Robber Kitten—nearly three minutes of footage—when Ambrose encounters Dirty Bill (voiced by Billy Bletcher), a genuine criminal wanted for robbery. (An original storyboard drawing, which can be seen in the book Mickey and the Gang, lists additional charges besides robbery: murder, theft, arson, burglary, homicide, matricide, patricide, regicide, infanticide [!], and a scribbled addition below, insecticide.) With this sequence, Ambrose and Dirty Bill speak their dialogue in a natural fashion, rather than with rhyming couplets as in subsequent Silly Symphonies, which are still utilized for the kitten’s first couple lines of dialogue.

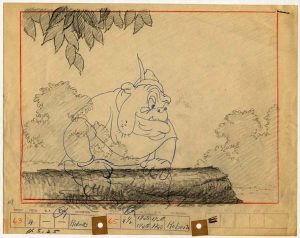

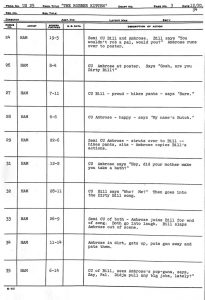

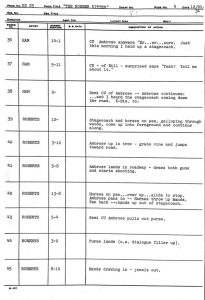

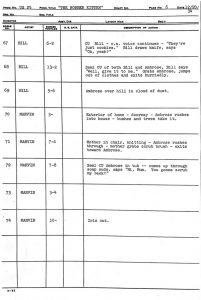

In Luske’s sequence, Ambrose pokes one of his popguns behind Dirty Bill, who reaches for his nearest weapon before the little kitten’s voice cracks in the midst of his threat. After they introduce themselves, Dirty Bill invites Ambrose to sit down with him on a log. To make an impression on his new friend, the little kitten mimics his every movement, including a moment where he fails to eject spit at a far distance. The sequence also includes the brief song “Dirty Bill (from Cootie Hill),” written by Frank Churchill, which deepens their friendship—and itself seems based on “Railroad Bill,” a 19th century standard. But then Dirty Bill asks Ambrose if he managed any burglaries. The little kitten recounts the stagecoach robbery seen earlier in the film, recounting it as an actual robbery, staged in a fantasy sequence animated by Bill Roberts. With all the faux-bravado Ambrose gives himself with his story, it ends on an absurd conclusion as he puffs and beats on his chest, emitting a loud Tarzan yell (provided by Clarence Nash).

In Luske’s sequence, Ambrose pokes one of his popguns behind Dirty Bill, who reaches for his nearest weapon before the little kitten’s voice cracks in the midst of his threat. After they introduce themselves, Dirty Bill invites Ambrose to sit down with him on a log. To make an impression on his new friend, the little kitten mimics his every movement, including a moment where he fails to eject spit at a far distance. The sequence also includes the brief song “Dirty Bill (from Cootie Hill),” written by Frank Churchill, which deepens their friendship—and itself seems based on “Railroad Bill,” a 19th century standard. But then Dirty Bill asks Ambrose if he managed any burglaries. The little kitten recounts the stagecoach robbery seen earlier in the film, recounting it as an actual robbery, staged in a fantasy sequence animated by Bill Roberts. With all the faux-bravado Ambrose gives himself with his story, it ends on an absurd conclusion as he puffs and beats on his chest, emitting a loud Tarzan yell (provided by Clarence Nash).

Roberts’ animation continues when Ambrose shows Dirty Bill his “swag” bag—containing pilfered cookies, though Bill cannot see inside. Believing the small bag is filled with riches, Bill is overcome with snarling, drooling avarice. In a nervous chuckle, Ambrose tells the truth about his meager bounty but Dirty Bill bears down on him, brandishing a knife. (Roberts had earlier animated the district attorney cat in Pluto’s Judgment Day, a vicious, fanged character whose motions foreshadow Roberts’ animation of Dirty Bill in these scenes.) Trembling for his life, Ambrose jumps out of his clothes and makes a fast dash for home, again animated by Roberts. Following Ham Luske’s animation in The Tortoise and the Hare, Roberts was another animator that excelled in speed lines augmented by dry-brush work (i.e. the district attorney parrot in Who Killed Cock Robin). Marvin Woodward animates the ending scenes of Ambrose jumping into his bath, with his mother glaring at him with her brush in hand, no doubt intended for disciplinary means.

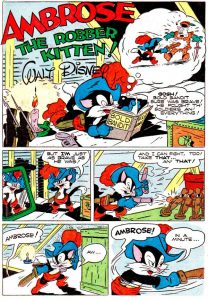

The animation for The Robber Kitten was completed by February 19th, 1935. A few days later, a newsprint adaptation of the film was published on the Silly Symphonies Sunday color pages, written by Ted Osborne and drawn by Al Taliaferro. The comic strip adaptation itself improves the narrative of its screen counterpart in several ways. Ambrose decides to become a robber upon seeing Dirty Bill’s wanted poster outside on a tree after he is ordered to retrieve milk and bread by his mother. When Ambrose encounters Dirty Bill at his hideout, the criminal bulldog turns him away instead of befriending him based on common ground. To prove his mettle, Ambrose steals a few gold coins from his mother’s teapot, but Bill demands the rest. Meanwhile, Ambrose’s mother summons the king’s troops and they locate her son, along with Dirty Bill. When Bill is arrested, he implores Ambrose not to follow in his unlawful path. Ambrose runs home to his mother and returns her gold coins. In the debut issue of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories (October 1940), which consisted mainly of reprinted material, The Robber Kitten was reprised as a text story, except the kitten is named “Fearless Frank.” A redrawn version of the story appeared in the second issue of Walt Disney’s Christmas Parade, published in November 1950.

The animation for The Robber Kitten was completed by February 19th, 1935. A few days later, a newsprint adaptation of the film was published on the Silly Symphonies Sunday color pages, written by Ted Osborne and drawn by Al Taliaferro. The comic strip adaptation itself improves the narrative of its screen counterpart in several ways. Ambrose decides to become a robber upon seeing Dirty Bill’s wanted poster outside on a tree after he is ordered to retrieve milk and bread by his mother. When Ambrose encounters Dirty Bill at his hideout, the criminal bulldog turns him away instead of befriending him based on common ground. To prove his mettle, Ambrose steals a few gold coins from his mother’s teapot, but Bill demands the rest. Meanwhile, Ambrose’s mother summons the king’s troops and they locate her son, along with Dirty Bill. When Bill is arrested, he implores Ambrose not to follow in his unlawful path. Ambrose runs home to his mother and returns her gold coins. In the debut issue of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories (October 1940), which consisted mainly of reprinted material, The Robber Kitten was reprised as a text story, except the kitten is named “Fearless Frank.” A redrawn version of the story appeared in the second issue of Walt Disney’s Christmas Parade, published in November 1950.

Technicolor photography on the Disney cartoon occurred in March 1935, as the Robber Kitten comic continuity ran in weekly installments in the Sunday newspapers. The film first opened in New York theaters on April 18, while the Sunday comic ended just three days later. A month after its release, Motion Picture Daily reported the Pennsylvania censor board withheld the film on the ground that “it would have an unwholesome influence on children because it showed kittens as robbers, stickups and gangsters.” In August, special scenes for the Italian version were photographed—one can assume that Dirty Bill’s English-language wanted poster was one of the significant changes.

After the film’s release in August 1935, The Robber Kitten underwent a critique in its story and characterization by various staffers, including director Dave Hand. In the case of Ambrose, George Drake (supervisor of the in-betweeners) commented: “I think his character could have been much more successfully displayed as a little kitten boy who was basically good and wanted to do right, but whom temptations got the better of. The contrast that would have been established by such a demonstration of his make-up would have made him a lot more human.” As for the villain, Bill Shull (an assistant animator) lent a valid statement, especially considering the character’s more complex role in the Silly Symphonies comic adaptation: “Dirty Bill is a good character, but he simply had nothing to do in Robber Kitten.” On the other hand, story artist Otto Englander stated, “Dirty Bill in Robber Kitten was one of the best villains I ever saw. I wish we could use him again somewhere.” In fact, Dirty Bill made appearances in the early Donald Duck comic book adventures drawn in England during the late 1930s, as Eli Squinch’s hired muscle.

Enjoy! Maybe your opinion on the film is different from its own creators…

Click to enlarge each draft page:

(Thanks to JB Kaufman and Dave Gerstein for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Hardaway and Dalton seemingly worked this story five years later in Fagin’s Freshman (1939), even having their kitten named Ambrose (” ….but the kids call me ‘Blackie'”).

Another great breakdown! Love these posts. This reminds me of a Warner Brothers cartoon whose title escapes me at this moment; the little cat character also identified himself as Ambrose (“Ambrose Wilber Scats, but the kids all call me Blackie!”) and he falls in with a band of petty thieves who are led through a chorus of “We’re Workin’ Our Way Through College” with altered lyrics. The cartoon begins with Mama Cat leading her kitties in the old standard “Three Little Kittens” Rhyme before Ambrose angrily stomps out of the room to turn on the radio to a radio crime drama. Mama shuts off the radio, scolding Ambrose for distracting the little sing-along (or, more accurately, recite-along), sending Ambrose to his room. Ambrose somehow escapes from the house and finds out about these band of gangsters and wants to join up…until he realizes that the “play” includes real guns and bullets and the men are being trained to commit serious crimes.

I am curious about other voices in “ROBBER KITTEN” just as I’m curious about the voices throughout the Warner Brothers remake. I know that Walter Tetley did the voices of some small characters at Warner Brothers, as he did in the later cartoon, “THE HAUNTED MOUSE”, but how many other voices did he do before becoming widely known as the voice of Sherman in Jay Ward’s “MR. PEABODY’S IMPROBABLE HISTORY”? There are so many childlike voices heard in 1930’s cartoons, including the voice of Felix the Cat in the three Van Buren cartoons, but I guess that actual records on such things are very difficult to find…and other versions of this scenario were created at other studios. One might say that “SMALL FRY”, from the Fleischer Studios, might have been slightly influenced by this particular SILLY SYMPHONIES title.

Walter Tetley was also the voice of ANDY PANDA for Walter Lantz in the mid 1940s. As the the influence on the Fleischer cartoon, SMALL FRY, I don’t see any connection. That cartoon was something of a sequel to their Color Classic, THE EDUCATED FISH (1937) It is my belief that this sequel may have begun at the time of the Strike and was picked up for completion a year later once the studio had moved to Miami.

Disney seemed to like doing cartoons with disabled characters, whether they be blind, missing limbs or growing bat wings.

I wouldn’t go so far as to “accuse” Disney of deliberately making cartoons about “disabled” characters, as they were only a part of classic stories, which recognized the existence of such figures. Regardless of the “motivation,” perhaps he was ahead of his time by portraying them, and doing in in a way that did not ridicule them but give them sympathy.

Dirty Bill appears briefly in “Toby Tortoise Returns”. He’s one of the audience at the boxing match, sitting next to the Big Bad Wolf with Goofy, Donald Duck and others nearby. The gag is they’re all on first name basis with Jenny Wren, who sashays in ala Mae West.

Prominently featured on the side of the stage coach is a sign saying “Body By Fisher”. Fisher Body started in 1904, and originally made bodies for stagecoaches and horse drawn wagons, their trademark was a stagecoach body. They were sold to General Motors in 1919. Could this be an early example of product placement in movies, and could General Motors have put money in to Disney Productions, including “The Robber Kitten”? Or was this just a gag using the familiar Fisher Body trademark just for the fun of it?

The use of “Fisher Body” was more of a cultural/awareness joke than a deliberate “product placement.” I do not believe that General Motors had any investment in Walt Disney Productions since they had more influence at Jam Handy, which was three blocks down the street.

A powerful cartoon. The opposing elements of horseplay and REAL danger are effectively presented. I thought the golden Star of David was a cute touch in the stagecoach robbery scene. Thanks for a fascinating breakdown!

Thank you, Jonathan Wilson, for clearing my addled brain; yes, “FAGIN’S FRESHMEN” was indeed the cartoon from Warner Brothers that I was trying to think of, and again, it still remains a mystery as to who did the voices throughout that one.

Love Ham Luske’s animation of Dirty Bill, especially the treatment of his jowls, with a convincing sense of weight and loose flesh. I believe Ward Kimball was his assistant at the time, so there might be some of his drawings mixed in there.

Devon,

Your thorough account of the production is fantastic. This raises the question of exactly HOW Animation Directors at Disney functioned at this time. The role of Animation Director seemed to vary from studio to studio. So it would be most interesting to see an explanation of this particularly since most people do not know what an Animation Director does or “did.”

I think it is a great cartoon. I have forgotten that the kitten in “Fagin’s Freshman” was named Ambrose too. By comparing the two shorts I think The Robber Kitten is the funnier cartoon overall, but Fagin’s has way more funny gags near the end.

Oddly for a WB cartoon, “Fagin’s…” feels more preachy that its Disney counterpart, it seems as Hardaway at Warners was trying to make a weird point that liking crime stories over sappy songs somehow makes you a delinquent. I can imagine adults (and most children) in the theater audience rolling their eyes at the beggining of that cartoon.

The Robber Kitten in the other hand acknowledge the fun of mischief, and Ambrose is more of an active protagonist. In the later cartoon, the kitty almost disappeers of the story as soon as the police dogs arrive. The gags that followed that scene are some of the best for a 30s cartoon, though. I theorize the writers came with those gags first, and later add the kitty`s storyline to have a plot.

I don’t remember any character with disabilities in the Disney short, so I don’t get that criticism.