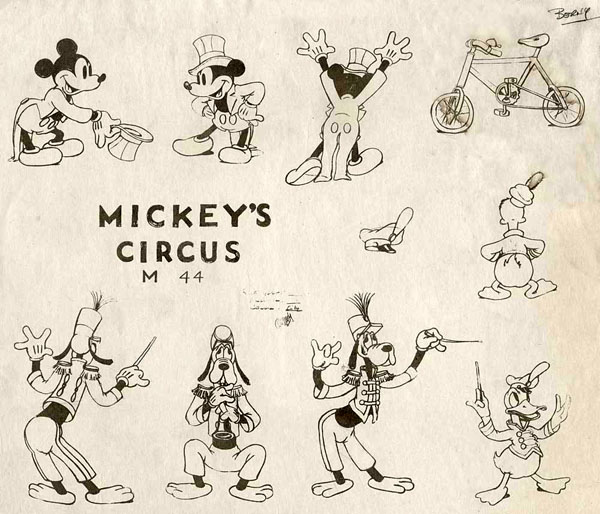

On September 18, 1935, a story outline for Mickey’s Circus described a production that would provide “a continuous flow of gags…everything to create the spirit of a circus.” As written, Mickey introduces his first attraction: the great equestrian act, with Mademoiselle Clarabelle Cow and her “Wonder Horse.” The outline suggested depicting a “good burlesque” with this act: “When she puts him through his dancing tricks, his actions are almost human. Also, his reactions to Clarabelle’s treatment, such as scolding or kissing.” The original story also proposed that Goofy could be included in the act as a ringmaster or a property man. The circus audience was comprised of the rambunctious little mice orphans, used in a few Mickey cartoons. They atypically behave themselves during the equestrian act.

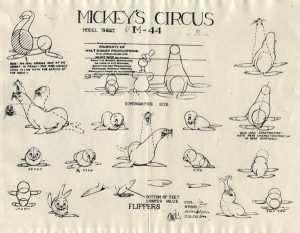

After Clarabelle finishes, Mickey introduces the second act: Captain Donald Duck and his trained seals. Proudly entering the arena, Donald’s temper is flared by a little seal that continuously interrupts his performance. The outline dictated that the orphans would incite further disruption during this second act, presumably taunting Donald at any given moment, reminiscent of their interactions in Orphans’ Benefit. Mickey tries to silence the children, but several orphans run towards a large cannon intended for the human cannonball act, and Mickey rushes to save them.

Without a ringmaster to maintain order, the throng of orphans run loose and overrun the entire show. Amidst the mayhem, the children now assume the roles of the performers, while Clarabelle, Goofy, and Donald are either locked in cages or made to perform. One possible gag in the outline involved Clarabelle riding Goofy around the ring, with her educated horse acting as the ringmaster. The outline concluded that a “blackout finish” was needed, and emphasized “the most successful comedy gags will be the ones in which the character of the animal or performer is brought out, not necessarily the wild action gag.” Gag submissions from the staff were to be delivered to Harry Reeves by October 2.

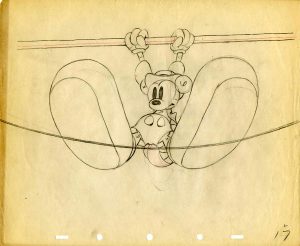

Two consecutive story conferences were conducted October 20 and 26. Walt Disney, Ted Sears, Otto Englander, and Jack Kinney discussed the scenes of Captain Donald Duck with his trained seals in the latter meeting. Between the September outline and the October meetings, a new continuity involving Mickey and Donald precariously balancing on a high wire was put through development. Al Eugster, an animator on Mickey’s Circus, noted in his diary another story meeting that occurred on December 9. Animation commenced the following month. Eugster started work on his scenes of Mickey and Donald in the climactic high wire sequence on January 16, 1936. A “sweatbox” session—a scrutinizing of his rough pencil tests—followed on February 10.

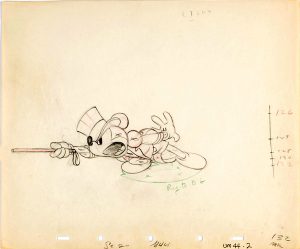

The great equestrian act with Clarabelle Cow and Goofy was ultimately omitted from the cartoon, which aimed its focus on Donald Duck. By the time Mickey’s Circus entered story development, the petulant Duck had risen to stardom with audiences. It was intended in the original September outline for Donald to play a practical joke on the seals: each seal would receive a fish after their juggling routine, but the fish would be attached to a rubber band, and retracted back to their master. Ted Sears remarked in the October 26 meeting, this would be used “just once…not running gag…little fellow doesn’t deserve one again,” referring to the little seal that acts as a nuisance throughout the show. This mean prank was excised, instead allowing the sequence to be carried by Donald’s combustible temper. During its animation, Mickey’s Circus became a milestone for the younger artists that endured extensive training at Disney’s in the early thirties. Milt Kahl is credited for the animation of ringmaster Mickey at the start of the film—his first significant assignment. When director Ben Sharpsteen handed out the scenes, he insisted Kahl make a series of pose drawings to “show him what I was going to do with it.” After Kahl finished the scene and brought his work to Sharpsteen, he flipped through the drawings, then sat staring out a window for a long period of time, which made Kahl apprehensive. Finally, Sharpsteen said, “All right, that looks pretty good.” Frank Thomas was given his first solo effort in Circus, animating many of the scenes of Donald’s seals begging and scrambling over each other for a fish. In later years, Thomas recalled flipping his drawings for Hollywood celebrities Douglas Fairbanks and his wife Lady Sylvia Ashley during their tour of the studio.

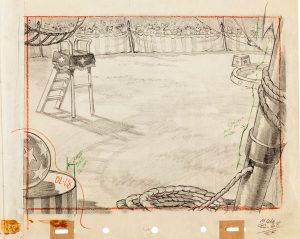

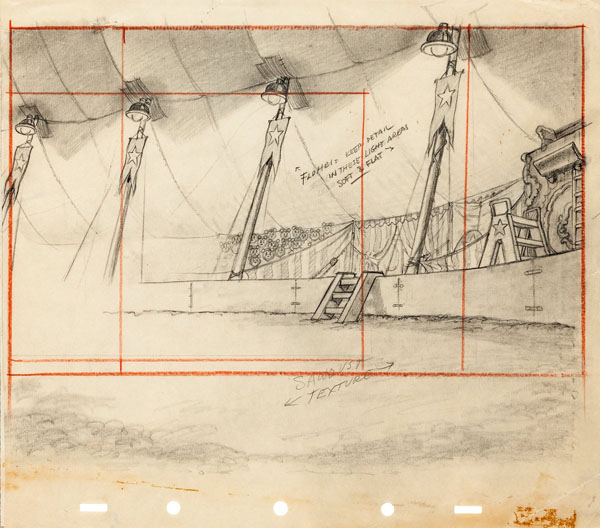

A background layout drawing with written notes addressed to “Carlos,” an indicator that Carlos Manriquez was one of the background painters on this film. Click to enlarge.

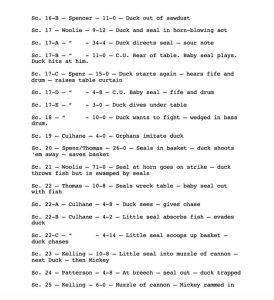

Two noteworthy animators are credited for the scenes of Donald Duck’s circus act: Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman and Fred Spencer. Reitherman animated Donald’s introduction, with his seals following him, his first altercation with the baby seal, and their juggling tricks. Spencer’s animation takes over when Donald throws two fish to each of his large seals, only for the third to be swiped by the baby seal. Reitherman’s work resumes with Donald commanding one seal to blow musical horns to the tune of “Comin’ ‘Thro the Rye,” which the little seal interrupts with a rendition of “Yankee Doodle.” Bearing a resemblance to Donald’s disruptive flute-playing of “Turkey in the Straw,” as a substitute for Rossini’s “William Tell Overture” in The Band Concert, the roles of tormentor and tormented are now reversed.

Next, Spencer animated the baby seal’s second rendition of “Yankee Doodle,” playing a fife and drum underneath the table, Donald diving into the table, his body stuck in the bass drum, and firing his gun to dispel the hungry seals from the fish basket. Reitherman concludes the sequence when Donald plants both feet on the basket lids, but the seal refuses to play music until he is assured a fishy reward. Once Donald presents him with a fish, the seal plays a rapid succession of horn blasts.

By the time Mickey’s Circus entered its animation stages, Spencer had become a proficient animator with his work on Donald. He animated many scenes of the Duck throughout Orphans’ Picnic, in which he redesigned Donald from the goose-like appearance of his earlier roles. Later, in Moving Day, Spencer handled an extended sequence of Donald’s complications with a plunger and a fishbowl. Reitherman had animated moderate scenes in several Mickey Mouse shorts and Silly Symphonies, but in Circus, he was entrusted with key sequences developing the Duck’s character, further advancing his position as a top animator. Throughout the cartoon, Donald gives disgruntled side glances to the camera—for instance, when the orphans applaud after the little seal’s rendition of “Yankee Doodle”—that are reminiscent of Oliver Hardy’s indignant looks to the audience in the Laurel and Hardy films. (In a more obvious reference to contemporary cinema, another of the performing seals assumes the role of Charlie Chaplin during the introduction of Donald Duck’s act.)

In a true “all hands on deck” approach, Ben Sharpsteen assigned any possible animator to a scene, with some artists credited for less than five small bits of footage in the frantic events that follow. This resulted in a total of nineteen artists credited in the production draft. While each of the three seals fight over their prize, they destroy the musical horns and the baby seal emerges out of the swarm, narrowly absconding with the fish until Donald shouts at him. The orphans rescue the little seal, stuffing Donald and ringmaster Mickey inside a cannon and firing upwards, landing them on a high wire. Scene 32, credited to Jack Hannah, showcases depth and volume effectively as Mickey wobbles on the tightrope; his body turns and flips with his shoes close to the foreground.

The production draft lists a few scenes that were ultimately cut from the final film, presumably to enliven its fast action. Scenes 33 to 36 reveal the circus band imitating the actions of Mickey’s somersault on the high wire, then cuts to Mickey spinning fast in a whirling action, and the band mimic the same action, ending in a fanfare. Mickey is tangled up in the tightrope, and is laughed at by Donald. As seen in the cartoon, the action of Mickey’s high wire act in scene 32 cuts to Donald laughing in scene 37.

Later, one of the orphans flips a high voltage switch to 110 volts, electrocuting Mickey and Donald. In the film, three different switches are shown on the circuit board, but only two are activated, with the other set to 4,000 volts. The draft indicates that all three switches were triggered, causing a powerful electrical current that also affects the circus band. However, the action cuts from scene 64 of the orphan turning the switch to its highest setting to scene 67, when the high wire snaps in half, causing the two performers to descend into a seal tank filled with water.

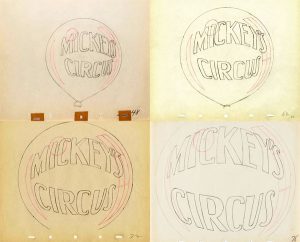

The film elements of the original main title sequence have yet to surface, but many sequential animation drawings have survived. The version commonly circulating has the usual “burlap titles.”

The original September story outline proposed “the title music will be a loud fanfare, including all the well-known circus noises, barkers, animals…” While there are no barkers or other circus animals besides sea lions in the film, the cartoon opens with a rousing, fast-tempo version of John N. Klohr’s “Billboard March.” Musical composer Paul J. Smith (1906-1985) encapsulated the spirit of a circus, as the story outline encouraged, in his score throughout the cartoon. (Smith is not to be confused with the Lantz animation director Paul J. Smith, born the same year. To further complicate matters, the middle name of both Paul Smiths was Joseph.)

Other compositions Smith incorporated are a brisk rendition of Kerry Mills’ “At A Georgia Camp Meeting” when Donald and his seals are introduced; Juventino Rosas’ “Over the Waves (Sobre las olsas),” a Latin American waltz that became synonymous with stage performances, especially circuses. Jacques Offenbach’s most notable composition, “Galop Infernal” from his opera Orphee aux Enfers, is played in a hurried tempo to emphasize the chaotic tension of Mickey and Donald’s perilous tightrope act. (In the October 26 story meeting, Walt Disney originally requested that the circus band perform “Sailing, Sailing (Over the Bounding Main)” during this sequence.)

Mickey’s Circus was previewed on June 19, 1936, as noted in an entry in Al Eugster’s journal. That same month, Good Housekeeping magazine published their monthly Disney adaptation of the cartoon. This version of Circus had its story modified slightly, with a few alterations from its screen counterpart. While the magazine feature retained the central theme of Mickey managing a circus (and Donald’s performing seals), the story implied an amateur circus in the vein of an Our Gang comedy, with costumed house pets billed as wild animals. In addition, both Mickey and Donald are both depicted as capable entertainers performing their own tight rope acts.

On August 1, Mickey’s Circus was officially released to theaters. A few months later, the short had its New York opening at Radio City Music Hall during the weeks of November 19 to December 2. The engagement during this run presented a fully prismatic event: the Technicolor cartoon was on the bill with The Garden of Allah, produced by David O. Selznick, starring Charles Boyer and Marlene Dietrich, and noteworthy as the third live-action feature filmed in three-strip Technicolor.

In the October 1935 story meeting for Mickey’s Circus, Walt Disney had broached many different pieces of comic business for the troublesome baby seal. Otto Englander suggested in that conference, “How about dressing up [the] little seal with [a] clown hat and collar?” to which Walt replied, “Yes, if he looks cute. [We] might keep them more like seals, though, if they aren’t dressed.” The idea of the little seal as a clown might have been eliminated, but Walt’s personal obsession with the character prevailed even after the film’s release. Convinced that audiences loved the baby seal’s antics in Circus, Walt demanded that he be inserted into several shorts that ultimately went unfinished. Eventually, the baby seal made it to another completed cartoon in Pluto’s Playmate (1941), written and storyboarded by animators Ray Patterson and Grant Simmons. The seal went on to appear as Pluto’s friendly rival in two more Disney shorts released in the late forties, Rescue Dog (1947)—for which he received his enduring name of Salty—and Mickey and the Seal (1948). Much later, in the early 2000s, he was revived for a number of Mickey MouseWorks, House of Mouse, and Mickey Mouse Clubhouse television episodes.

Enjoy the show, folks—admission is just one thin dime, with kids admitted free! (If the embed below does not work on your browser – click here)

Background layout with notes addressed to Emil Flohri, another background painter on Circus. An experienced political cartoonist and magazine illustrator, Flohri joined the studio in 1930 when he was in his early sixties.

(Thanks to JB Kaufman, David Gerstein, Hans Perk, Mark Mayerson, John Canemaker, and Didier Ghez for their help.)

And finally, in case many of you haven’t seen it, here is a link to my new blog, Pegbar Profiles, which offers biographical overviews of classic animators, with Emery Hawkins as the first subject!

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

It’s not surprising that so many animators were assigned to “Mickey’s Circus”. In 1936, when the studio was gearing up for “Snow White”, this would have been an opportunity for the younger artists to show what they could do, to demonstrate their strengths. Some, like Kahl and Thomas, would be permanently assigned to features; other, like Hannah and Couch, to shorts. Even so, Fred Spencer animated the majority of Donald’s solo scenes, as he had been doing since “Mickey’s Service Station”.

Woolie Reitherman would later be Disney’s go-to man for animating large animals: Monstro the whale in “Pinocchio”, the dinosaurs in “Fantasia”, the crocodile in “Peter Pan”, etc. So it’s interesting that he was given the (sea) lion’s share of scenes involving the adult seals in “Mickey’s Circus”. While the cartoon may have called for “all hands on deck”, it’s certainly not a case of “too many cooks”!

I’m unable to play the video on the embed, or via the link

Logging on to Google works for me.

Have you tried using different browsers?

Your new blog looks very exciting, Mr. Baxter! Can’t wait for future posts!

Excellent article, Devon. Thank you 🙂

I wish they’d kept in more acts, characters and more of the band, while cutting some of the Donald and the seals stuff. That would have made the cartoon much more of a circus (as intended in the September ’35 outline) and, in my opinion, more fun.

Interesting you mention the original titles for this. I once spent some time looking across various auction sites to find as many of the drawings of it as possible, hoping to recreate it as best I could. I only managed to find 14 of them (the lowest was number 48 and the highest was 78, as in your illustration) so most of it was still missing. Maybe an original print will be uncovered some day and we’ll see them as intended again.

Fantastic read, Devon! Walt Disney sure had a way of orchestrating his team in such as fashion that they would expand their skill sets and reach their full potential, that the final product shows.

All the best on your new blog.

the shot of Mickey swinging on the haywire was referenced in “The Thief and The Cobbler” when the thief tries getting to the minaret.