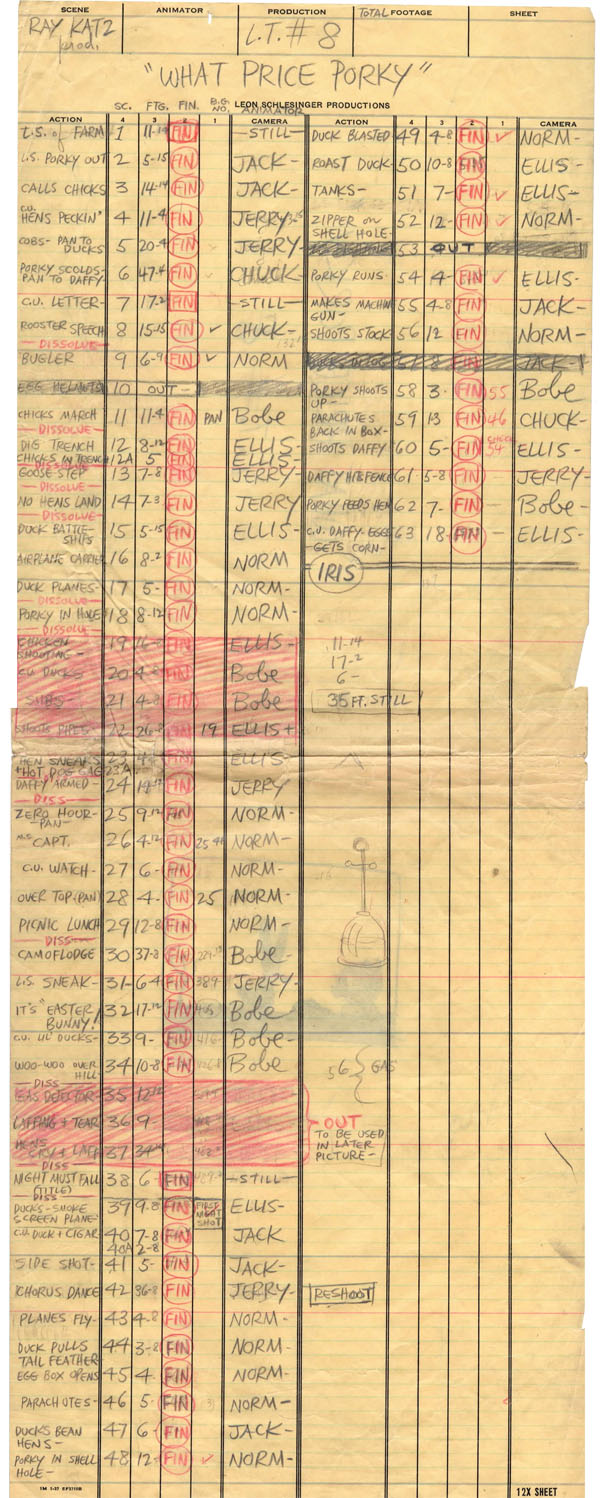

In my research of the animator drafts (“dope sheets”) for Bob Clampett’s first season of black- and-white Looney Tunes, I have learned that Clampett and Chuck Jones actually shared the directorial position for three films—being given dual credit in the production documents on Rover’s Rival, Porky’s Hero Agency, and Porky’s Poppa. But the production draft for Clampett’s next Looney Tune, What Price Porky, reveals no such distinction. Rather than sharing the directorial credit with Clampett, Jones merely shares the “animation” credit with Bobe Cannon, as he does in the finished film.

The “dope sheets” (production drafts) for the first four Looney Tunes directed by Clampett include start dates for pencil animation, but the draft for Porky’s Poppa does not, and What Price Porky follows suit. So when did pencil animation for What Price begin? Given that the “Katz unit” animators began work on a new Looney Tune once per month, an educated guess points to about September 1937—two months after work on Hero Agency began.

The “dope sheets” (production drafts) for the first four Looney Tunes directed by Clampett include start dates for pencil animation, but the draft for Porky’s Poppa does not, and What Price Porky follows suit. So when did pencil animation for What Price begin? Given that the “Katz unit” animators began work on a new Looney Tune once per month, an educated guess points to about September 1937—two months after work on Hero Agency began.

Clampett’s early directorial efforts reflect the participation of animators from the Ray Katz unit, and their presence on, or absence from, individual films can tell us about the unit’s shifting makeup. (Katz’s unit occupied the first floor of the original animation building on Sunset Blvd., with Clampett and Jones as his animation supervisors, whereas Schlesinger’s other units were housed at the adjacent Vitaphone Building at Fernwood and Van Ness Avenues.) Bill Hamner, an animator who never earned screen credit in Clampett’s Looney Tunes, is listed in the production drafts for the first five; he is absent from the draft for What Price Porky, suggesting that he had left the Katz unit. Hamner later transferred to Walter Lantz and Screen Gems after working for Clampett.

Another artist was needed to fill the vacancy, so Clampett hired Isadore “Izzy” Ellis. Like Hamner and Jerry Hathcock, Izzy was formerly an artist in Ub Iwerks’s studio. As young cartoonists in the 1920s, Clampett and Ellis had their early work published in the “Junior Times” supplementary feature of The Los Angeles Times. Ellis is credited for several scenes in What Price Porky, though these weren’t his first for Clampett; he joined the Katz unit while pencil animation on Porky’s Poppa progressed and is credited for one brief shot near the finale.

In an interview with Michael Barrier and Milt Gray, Clampett fondly remembered devising the continuity for What Price Porky: “I wrote most of that as I was driving home, and I put the animation paper beside me on the seat of my car, and I’d be thinking of gags, and as I came to a stop light, I would jot down what I thought of. Then I took that, and I did draw up a complete storyboard myself.”

The warfare between Porky’s chickens and a gang of thieving ducks integrates World War I combat, the theme of several major motion pictures—the silent 1925 feature The Big Parade and three 1930 releases: Warner Bros.-First National’s The Dawn Patrol, United Artists’s Hell’s Angels, and Universal’s All Quiet on the Western Front, which was the Best Picture recipient for that year. The cartoon’s title alludes to the 1924 play and 1926 film adaptation of What Price Glory. Carl Stalling’s musical score establishes the subject matter under the main titles, with “Mademoiselle from Armentières,” a WWI-era tune more commonly known as “Hinky Dinky Parlez-Vous.”

The warfare between Porky’s chickens and a gang of thieving ducks integrates World War I combat, the theme of several major motion pictures—the silent 1925 feature The Big Parade and three 1930 releases: Warner Bros.-First National’s The Dawn Patrol, United Artists’s Hell’s Angels, and Universal’s All Quiet on the Western Front, which was the Best Picture recipient for that year. The cartoon’s title alludes to the 1924 play and 1926 film adaptation of What Price Glory. Carl Stalling’s musical score establishes the subject matter under the main titles, with “Mademoiselle from Armentières,” a WWI-era tune more commonly known as “Hinky Dinky Parlez-Vous.”

What Price Porky opens as rural farmer Porky wakes up to feed his chickens a helping of cracked corn. The poultry reacts by “peckin’” at their breakfast, spoofing a then-fashionable syncopated dance, where partners would face each other and bob their heads forward and back to each beat in a pecking motion. (The hep-cats in Katnip Kollege, released months after this cartoon, perform this move in various scenes throughout.) Porky then provides his hens with whole ears of corn. Without warning, a gang of black ducks greedily swipe their “cob on the corn,” leaving the poor hens hungry. Clampett’s love for comic strips is reflected in Porky’s pathetic attempts to reason with the ducks, borrowing a line from E. C. Segar’s J. Wellington Wimpy: “Someday, I’ll have you all over for a nice duck dinner—you bring the ducks.”

Repelled by Porky’s rambling, the ducks’ leader provokes the chickens with an insulting letter (after plucking a subordinate duck’s tail feather as an ad-hoc quill pen) that challenges the poultry to fight for their crop. The barnyard rooster is righteously affronted by the “fowl” language in the threatening note and rallies the hens to take action, which they enthusiastically accept. Clampett selected Chuck Jones to animate this sequence, which displays Jones’ strengths in animated acting and posing.

The leader duck signs his name as “General Quacko, Ducktator” on the letter; otherwise, internal documentation—including the draft— labels him as Daffy. (While Daffy appears here without his usual white neck-ring, another strong indicator of his identity is the trademark slurpy lisp heard later in the film when “Quacko” addresses Porky as the Easter Bunny.) Following the little black duck’s sensational debut in Tex Avery’s Porky’s Duck Hunt, a resulting Technicolor film, Daffy Duck and Egghead, was put into quick production; What Price Porky would be his third appearance.

The leader duck signs his name as “General Quacko, Ducktator” on the letter; otherwise, internal documentation—including the draft— labels him as Daffy. (While Daffy appears here without his usual white neck-ring, another strong indicator of his identity is the trademark slurpy lisp heard later in the film when “Quacko” addresses Porky as the Easter Bunny.) Following the little black duck’s sensational debut in Tex Avery’s Porky’s Duck Hunt, a resulting Technicolor film, Daffy Duck and Egghead, was put into quick production; What Price Porky would be his third appearance.

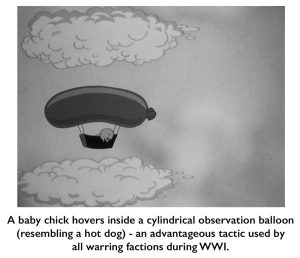

In a series of isolated sequences, the hens and ducks prepare for battle, satirizing past and current world events with the opposing battalions. Upon hatching, newborn chicks pose as WWI-era doughboys, wearing their eggshells as Brodie helmets; the hens then dig a trench for their brood to fight in. Once the chicks and ducks settle inside the trenches, one duck volunteers to plant a “No Hens Land” sign— a play on “No Man’s Land “— between them. (Later in the film, a sentry duck spots a hen crawling past the terrain, exclaiming, “Who goes there?” in a voice closely resembling Donald Duck’s!)

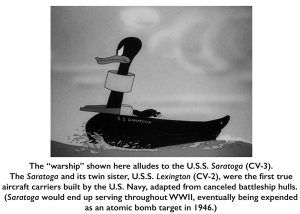

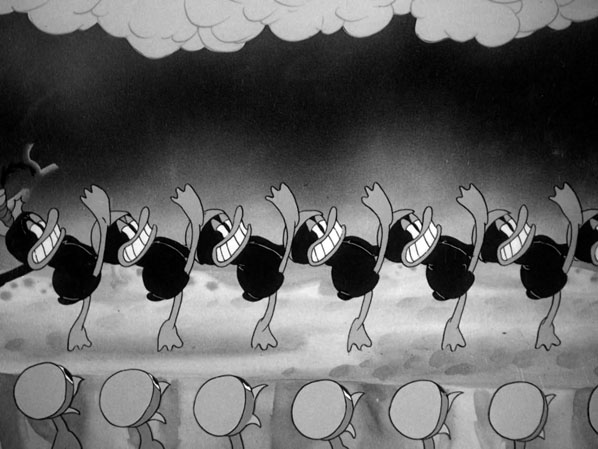

The ducks are portrayed as “blackshirts” (represented by their black feathers and helmets), patterned after Fascist Italy’s armed squadron under Benito Mussolini’s reign in the Spanish Civil War. (This was an ongoing occurrence during this cartoon’s production and familiar to movie audiences via newsreel footage.) The ducks utilize more advanced weaponry than the baby chicks; they position swans and geese as battle carriers and aircraft in scenes that correlate with the Italian naval and air support crucial to the success of the Falangist rebels— led by Francisco Franco— in their role during the Spanish Civil War. (What Price Porky even prefigured future developments in a scene where the duck soldiers goose-step past Daffy, deliberately modeled in this shot to resemble Mussolini with his prominent chin—Il Duce’s forces adopted this march after Hitler visited Italy in May 1938, two months after the cartoon’s release.)

The ducks are portrayed as “blackshirts” (represented by their black feathers and helmets), patterned after Fascist Italy’s armed squadron under Benito Mussolini’s reign in the Spanish Civil War. (This was an ongoing occurrence during this cartoon’s production and familiar to movie audiences via newsreel footage.) The ducks utilize more advanced weaponry than the baby chicks; they position swans and geese as battle carriers and aircraft in scenes that correlate with the Italian naval and air support crucial to the success of the Falangist rebels— led by Francisco Franco— in their role during the Spanish Civil War. (What Price Porky even prefigured future developments in a scene where the duck soldiers goose-step past Daffy, deliberately modeled in this shot to resemble Mussolini with his prominent chin—Il Duce’s forces adopted this march after Hitler visited Italy in May 1938, two months after the cartoon’s release.)

The production draft reveals a block of scenes animated but cut from the final picture, totaling over 30 seconds of screen footage. These excised scenes include a soldier chicken shooting at a troop of ducks and another containing submarines. The brief action descriptions in the draft are vague without the aid of Clampett’s original story sketches; scene 22 in the draft (“shoots pipes”) probably suggests the submarines firing bathroom sink pipes instead of torpedoes. Had the sequence remained, the barnyard naval conflict would have provided another allusion to the Spanish Civil War: Italian warships and “pirate” submarines attacked and sank Loyalist ships en route to Republican ports in the Mediterranean. (Directors Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton touched upon pirate submarines in Porky the Gob, released several months after What Price Porky.)

The production draft reveals a block of scenes animated but cut from the final picture, totaling over 30 seconds of screen footage. These excised scenes include a soldier chicken shooting at a troop of ducks and another containing submarines. The brief action descriptions in the draft are vague without the aid of Clampett’s original story sketches; scene 22 in the draft (“shoots pipes”) probably suggests the submarines firing bathroom sink pipes instead of torpedoes. Had the sequence remained, the barnyard naval conflict would have provided another allusion to the Spanish Civil War: Italian warships and “pirate” submarines attacked and sank Loyalist ships en route to Republican ports in the Mediterranean. (Directors Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton touched upon pirate submarines in Porky the Gob, released several months after What Price Porky.)

Norm McCabe handles the following sequence of the young chicks, now fully-grown adolescent doughboys, lined up and waiting tensely for the signal “at twelve” to climb over their trenches and advance into enemy territory. Their captain’s noon whistle sounds off, and the chickens clamber up the ladders, but instead of rushing towards the boundary line, the soldiers set up a tranquil picnic lunch. Theater audiences were already familiar with the trope of a band of soldiers ascending “over the top” in the aforementioned WWI-centric films, some of which likely included veterans of the AEF (American Expeditionary Forces).

Meanwhile, in a sequence animated by Bobe Cannon, General Quacko/Daffy disguises himself as the Easter Bunny, fashioning a handkerchief for rabbit ears and a cotton tail for good measure. He sneaks along the war-torn battlefield—an effectively atmospheric background layout — carrying a basket of Easter eggs. Cannon’s work continues when Daffy delivers the eggs to Porky; the decorated eggs crack open, and a bunch of pesky little ducklings charge at the dumbfounded pig. Daffy whooping excitedly, whirling, and bouncing off into the horizon is lifted from Clampett’s own animation in Porky’s Duck Hunt, though slightly modified to accommodate Daffy’s costume and Easter basket.

What originally followed, after Daffy’s mischievous prank, was a bout of chemical warfare, a highly formidable weapon introduced in World War I, used for comedic effect by Clampett. As the draft suggests, in scenes 35 to 37 (totaling 37 seconds of footage), the ducks deploy tear gas and laughing gas, which reduces the chickens to fits of sobbing and laughter—a reliable gag utilized in many film comedies before (and since). Perhaps to keep the cartoon at a standard runtime, Clampett opted to save the sequence for another production, as indicated by a scribbled note next to its action description.

What originally followed, after Daffy’s mischievous prank, was a bout of chemical warfare, a highly formidable weapon introduced in World War I, used for comedic effect by Clampett. As the draft suggests, in scenes 35 to 37 (totaling 37 seconds of footage), the ducks deploy tear gas and laughing gas, which reduces the chickens to fits of sobbing and laughter—a reliable gag utilized in many film comedies before (and since). Perhaps to keep the cartoon at a standard runtime, Clampett opted to save the sequence for another production, as indicated by a scribbled note next to its action description.

The battle rages into the night, allowing Quacko and his company to forge ahead past enemy lines; a thick smoke screen (emitted from above by a cigar-smoking little gray duck) separates the warring factions. The smoke rises like a stage curtain to expose Quacko and his fellow ducks sneaking up on the hens. They quickly burst into a chorus line routine, accompanied by “We’re Working Our Way Through College” (another Mercer-Whiting hit tune from WB’s Varsity Show) in the underscore. The doughboys applaud the performance, but the ducks mercilessly surround and pummel the helpless fighters. Amateur 16mm color footage, presumably shot by Clampett, shows the animators acting out the chorus line for the film—the 1975 documentary Bugs Bunny Superstar unearthed this rare, behind-the-scenes glimpse of the young artists in the Katz unit.

Carl Stalling’s musical score intensifies the night attack sequences via dramatic “mood music” by J. S. Zamecnik, intended to accompany silent movies; the cue sheet lists the composition as “Battle Music No. 9.” The cartoon license of newborn fowl hatching, whenever convenient, remains during the ducks’ airborne assault on the battle zone—eggs release like bombs and crack open a force of paratrooper ducklings that descend and bash the chickens’ helmets, accompanied by a xylophone effect, evoking a similar gag in The Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup (1933). During the melee, a flag-bearing duck rushes forward but is blasted away. He lands between two trees and clings to the flagpole. In the film’s only on-screen casualty, he meets his untimely fate when another explosion changes him into a roast bird on a spit. Armored tanks, another familiar sight in newsreel footage and war epics, appear briefly for a deliberately hokey punchline.

Carl Stalling’s musical score intensifies the night attack sequences via dramatic “mood music” by J. S. Zamecnik, intended to accompany silent movies; the cue sheet lists the composition as “Battle Music No. 9.” The cartoon license of newborn fowl hatching, whenever convenient, remains during the ducks’ airborne assault on the battle zone—eggs release like bombs and crack open a force of paratrooper ducklings that descend and bash the chickens’ helmets, accompanied by a xylophone effect, evoking a similar gag in The Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup (1933). During the melee, a flag-bearing duck rushes forward but is blasted away. He lands between two trees and clings to the flagpole. In the film’s only on-screen casualty, he meets his untimely fate when another explosion changes him into a roast bird on a spit. Armored tanks, another familiar sight in newsreel footage and war epics, appear briefly for a deliberately hokey punchline.

Clampett plays with the solidity of terra firma when Porky hides in a shell hole and pushes the ditch in different areas, while inside, to avoid deadly projectiles. When a mortar rolls into Porky’s improvised foxhole, he hops out and zippers the hole shut; the muffled explosion expands the ground like rubber. Porky takes the initiative to defeat the enemy; he uses a wringer washing machine as a Gatling gun, firing corn kernels and cobs. The ammunition effectively seizes Quacko’s blackshirts in a makeshift pillory and neutralizes a goose aircraft. Quacko sneaks up behind Porky to strike him with a mallet, but Porky intercepts with a corncob, which sends the general flying against a fence and jails him in a stockade. Triumphant farmer Porky lays down a victory feast of corncobs for his hens in front of Quacko, but the general still carries his basket of eggs, and more offspring pop out of them to snatch the corn. “Hinky Dinky Parlez Vous” returns in the musical score, played in mocking notes when the film irises out on Quacko and his cob-chewing conquerors.

The pre-production of What Price Porky in late 1937 coincided with the twentieth anniversary of the United States entering World War I in 1917. The cartoon premiered in Broadway’s Strand Theater on February 19, 1938, with another engagement at the Rialto Theater on March 5-19; the twentieth commemoration of the Armistice occurred nine months after the cartoon’s release. What Price Porky technically was Clampett’s first Looney Tune with Porky and Daffy; the young director saw great potential in the screwy duck and paired the two as an official screen duo in Porky and Daffy, which was released a few months later.

The pre-production of What Price Porky in late 1937 coincided with the twentieth anniversary of the United States entering World War I in 1917. The cartoon premiered in Broadway’s Strand Theater on February 19, 1938, with another engagement at the Rialto Theater on March 5-19; the twentieth commemoration of the Armistice occurred nine months after the cartoon’s release. What Price Porky technically was Clampett’s first Looney Tune with Porky and Daffy; the young director saw great potential in the screwy duck and paired the two as an official screen duo in Porky and Daffy, which was released a few months later.

(Thanks to Jerry Beck, Ruth Clampett, Eric Costello, Michael Barrier, Frank M. Young, David Gerstein, and Daniel Goldmark for vital information and assistance with this post.)

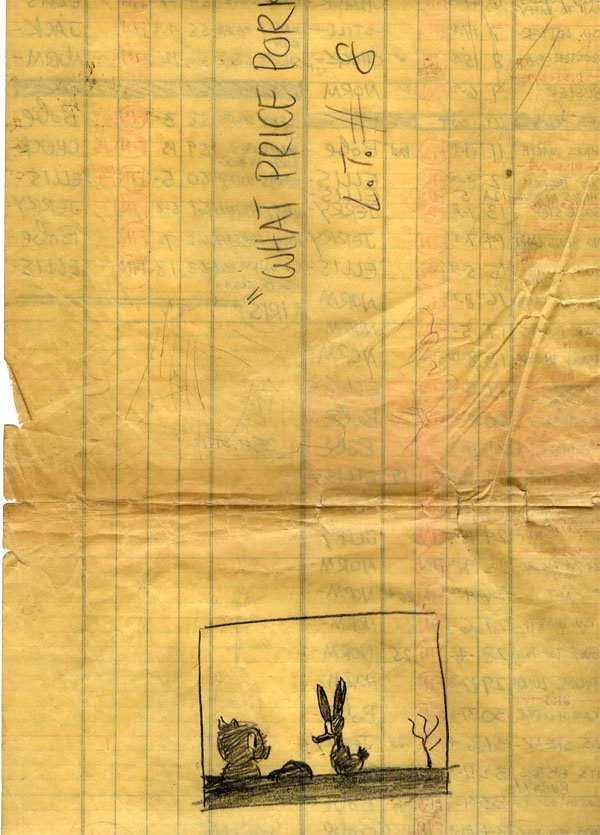

The reverse side of the draft features a thumbnail drawing by Clampett

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Fascinating stuff. I’m amazed that this material has survived after all these years.

“All the animators had trouble drawing [Porky],” Bob Clampett told Michael Barrier and Milt Gray in the interview cited above. “If you look scene by scene, you’ll see.” Having just done so, I can only conclude that the animators had gotten the knack of drawing the character by the time “What Price Porky” was made. I can’t detect any perceptible variation in Porky’s design whether he’s animated by Carey, Cannon, Jones, McCabe or Ellis. Maybe it helps that Porky isn’t onscreen for the majority of the cartoon.

The “peckin'” dance move of the Lindy Hop era played on the stereotypical African-American obsession with chicken. There was a song called “Peckin'”, the big show-stopping finale of the RKO musical “New Faces of 1937”, in which it was introduced by a trio of dancers known as The Three Chocolateers.

Nice to have the breakdowns back. Keep ’em coming!

Chuck Jones once insisted “Daffy has no teeth!” He certainly does in “What Price Porky.”

He’s also drawn with teeth in Chuck Jones’ own cartoon My Favorite Duck (when he does a classic sheepish grin) and also in Rabbit Fire when he’s pretending to be a dog. Pretty inconsistent rule if it was ever one.

That drawing of Porky and Daffy really warmed my heart, Thank you!👍

“TO BE USED IN LATER PICTURE”

…anything known about that?

At a convention some time back I saw a cel that looked like What Price Porky had been redrawn and painted in color, back when WB-7A went forth with that project. It obviously didn’t get syndicated (at least on our market) or maybe the redrawn What Price Porky never got finished.

At last, confirmation that the lead duck in the cartoon is in fact, Daffy.

As always, Devon, your in-depth analysis and close attention to detail is greatly appreciated. Looking forward to reading more from you.