With the acquisition of these drafts, animator breakdown videos showcasing films from Clampett’s unit will be a part of my semi-regular columns here on Cartoon Research. Concurrently, animator breakdowns of other, different titles from the Clampett archives will exclusively appear on my Patreon page.

Finally, since we only receive these animator drafts piecemeal, we implore readers not to request titles or the animator drafts themselves. Thanks for waiting patiently, and we hope our readers sincerely appreciate these pieces of history!

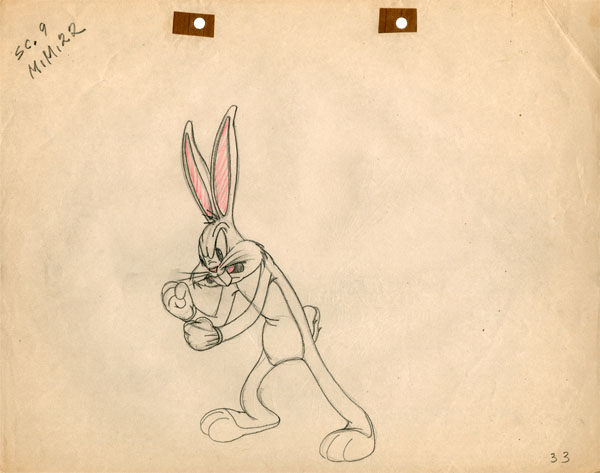

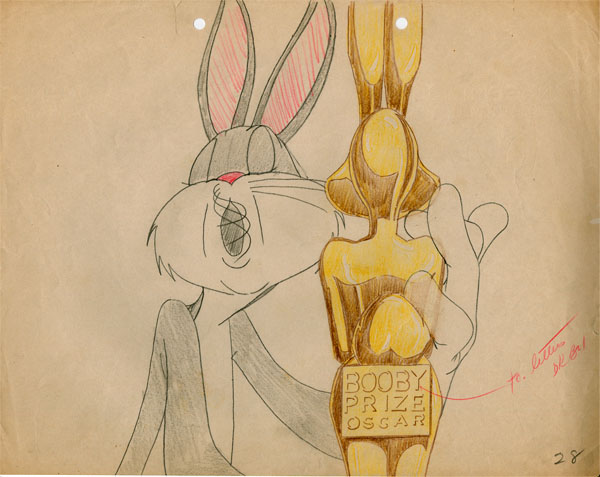

Production drawing courtesy of Paul Bussolini.

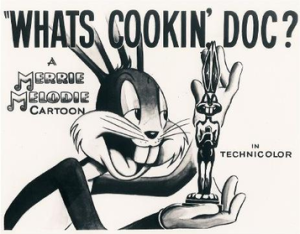

When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences introduced the category for Best Cartoon in 1932, producer Leon Schlesinger gained a nomination for Harman-Ising’s It’s Got Me Again (1932). The award went to Disney’s landmark three-strip Technicolor cartoon Flowers and Trees (1932). Disney received several more Oscars for his Silly Symphonies in subsequent ceremonies, but Schlesinger got no other nominations after that. In January 1938, Variety reported that Schlesinger resigned from the Academy due to discrimination; the Academy voted Schlesinger was limited to two entries for submission, while Disney was granted four. The following year, Fred Avery directed a travelogue parody Detouring America (1939), which earned the studio its second nomination.

Tex Avery’s A Wild Hare, released in July 1940, gave audiences the first definitive version of Bugs Bunny—self-assured in the face of danger—after Leon Schlesinger’s creative team made a few primordial attempts at a screwball rabbit character. The critical response to Avery’s cartoon earned the studio an Oscar nomination; it lost to MGM’s The Milky Way. Following the success of A Wild Hare, another Bugs cartoon, Friz Freleng’s Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt (1941), was among ten nominees from varying studios, such as MGM, Walter Lantz, George Pal, and Lawson Harris. Disney won the Oscar for the Mickey-Pluto cartoon Lend A Paw (1941), a reworking of Mickey’s Pal Pluto (1933). Meanwhile, Bugs’ popularity soared in the ensuing months, further heightening the reputation of the Warner Bros. style in animated cartoons. Nevertheless, the Schlesinger studio’s absence of Academy Award victories inspired Bob Clampett and his close collaborator, Mike Sasanoff, to craft a story where their star character exudes his status as a true Hollywood personality.

Tex Avery’s A Wild Hare, released in July 1940, gave audiences the first definitive version of Bugs Bunny—self-assured in the face of danger—after Leon Schlesinger’s creative team made a few primordial attempts at a screwball rabbit character. The critical response to Avery’s cartoon earned the studio an Oscar nomination; it lost to MGM’s The Milky Way. Following the success of A Wild Hare, another Bugs cartoon, Friz Freleng’s Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt (1941), was among ten nominees from varying studios, such as MGM, Walter Lantz, George Pal, and Lawson Harris. Disney won the Oscar for the Mickey-Pluto cartoon Lend A Paw (1941), a reworking of Mickey’s Pal Pluto (1933). Meanwhile, Bugs’ popularity soared in the ensuing months, further heightening the reputation of the Warner Bros. style in animated cartoons. Nevertheless, the Schlesinger studio’s absence of Academy Award victories inspired Bob Clampett and his close collaborator, Mike Sasanoff, to craft a story where their star character exudes his status as a true Hollywood personality.

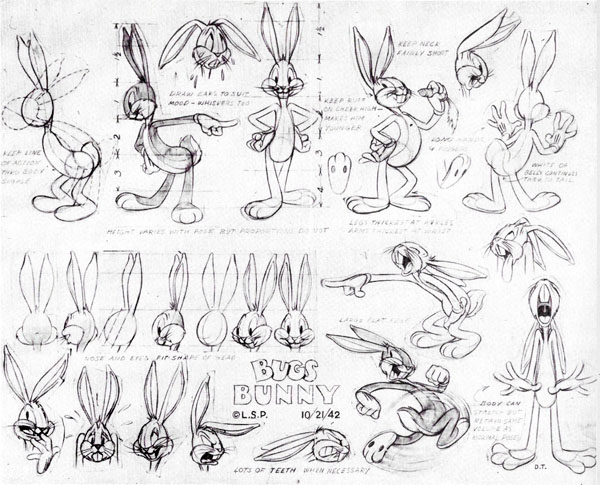

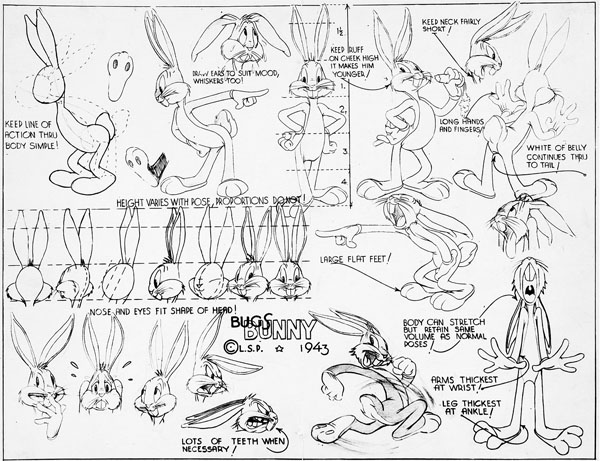

On November 14, 1942, Mel Blanc recorded the dialogue track for What’s Cookin’ Doc? Within two years, Bugs’ character rapidly matured in the hands of the studio’s principal writers and directors after the release of A Wild Hare. Two more dialogue sessions occurred months later during production, on October 30, followed by a “pick-up” session on November 6, 1943, which included the narration by Robert C. Bruce. Between the first initial 1942 recording and the additional “pick-ups” in late 1943, Schlesinger’s chief animator Bob McKimson designed a new model sheet of Bugs Bunny, augmenting one drawn by McKimson in October 1942. The revised 1943 model sheet cemented Bugs’ definitive look and was adopted by all the Warners directors in their cartoons.

On November 14, 1942, Mel Blanc recorded the dialogue track for What’s Cookin’ Doc? Within two years, Bugs’ character rapidly matured in the hands of the studio’s principal writers and directors after the release of A Wild Hare. Two more dialogue sessions occurred months later during production, on October 30, followed by a “pick-up” session on November 6, 1943, which included the narration by Robert C. Bruce. Between the first initial 1942 recording and the additional “pick-ups” in late 1943, Schlesinger’s chief animator Bob McKimson designed a new model sheet of Bugs Bunny, augmenting one drawn by McKimson in October 1942. The revised 1943 model sheet cemented Bugs’ definitive look and was adopted by all the Warners directors in their cartoons.

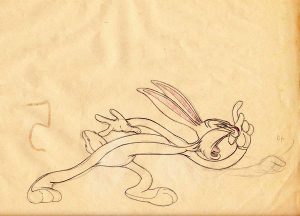

These changes to the rabbit’s design proved advantageous in What’s Cookin’ Doc. McKimson’s dimensional drawing and animation dominate much of the film. Clampett spoke highly of McKimson when casting him in scenes that required delicate character acting, “I felt [McKimson] had tremendous value because he had this tightness, and this little detail and I wanted to try and get a little fine acting, little things with the fingers, and things like that, just little actions on characters. With him, you wouldn’t have to sketch it as much as you’d just give him key sketches, little ideas, and then act it out for him. He’d get a lot out of it if you’d stand up, and I would actually make the movements and the little things. He’d come back [with his animation] like he’d photographed it mentally.”

October 1942 model sheet above; 1943 revised model sheet below.

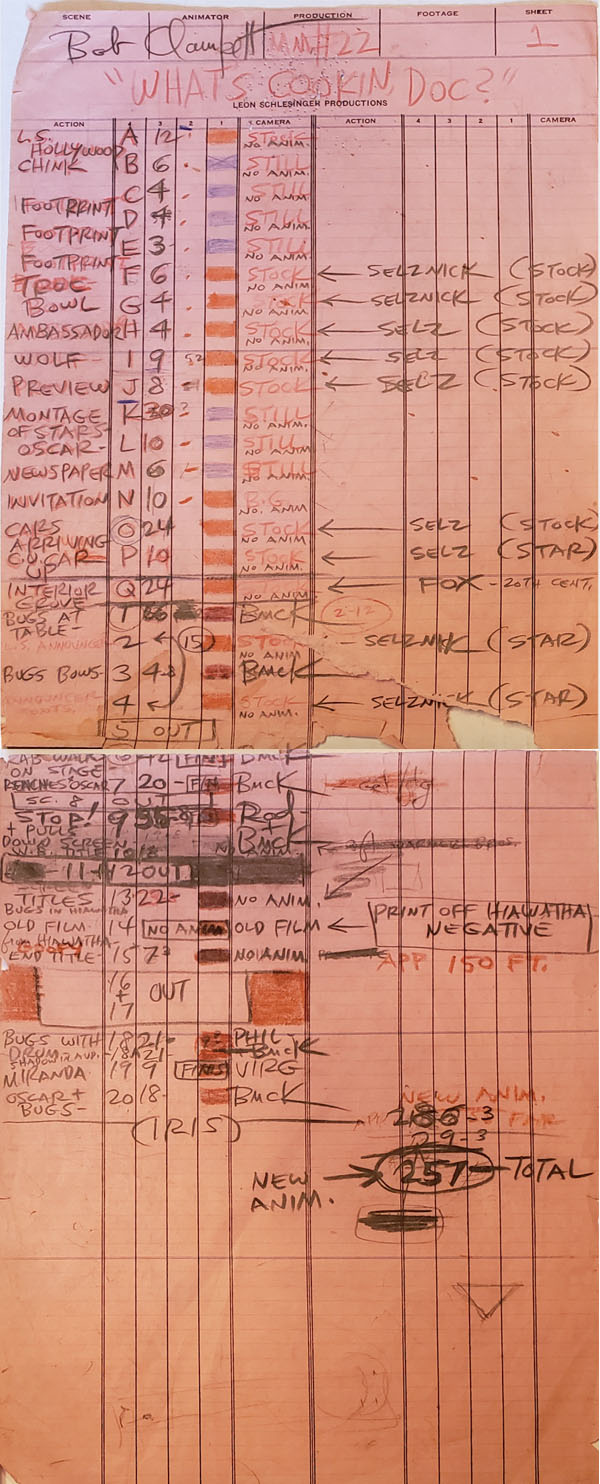

As a director, Clampett encouraged elaborate character animation in his 1940s cartoons. However, with the Schlesinger studio’s tight budgets, Clampett relied on various cost-cutting procedures for What’s Cookin’ Doc? For the newsreel-style introduction of Hollywood nightlife, stock footage of familiar sights such as Café Trocadero, Hollywood Bowl (sans amphitheater and distinctive bandshell), and the Ambassador Hotel’s Cocoanut Grove are represented, borrowed from the film library of top film executive David O. Selznick. Clampett also interspersed excerpts from 1937’s A Star is Born, produced by Selznick; the live-action scene of actor Paul Stanton presenting the Academy Award for Best Actor is dubbed by Mel Blanc. In the montage sequence built around the anticipatory excitement of the renowned Oscar statue, Clampett used magazine cut-outs of Hollywood figures on gradient-colored background cards.

Though the invitation card states the locale of the eighth annual Academy Awards gathering at the Biltmore Hotel, the live-action footage reveals both Grauman’s Chinese and the Cocoanut Grove hotel. In essence, the awards ceremony in Clampett’s film uses Grauman’s Chinese Theater’s exterior and the Cocoanut Grove hotel’s interiors. The eighth Academy Awards was held at the Biltmore on March 5th, 1936, with Frank Capra as master of ceremonies. (As president of the Academy, Capra denied Schlesinger’s discrimination charges against Disney and accepted the resignation from their committee.) The 15th Academy Awards was held a few months after the first dialogue recording at Cocoanut Grove on March 15th, 1943. James Cagney received an Oscar for Best Actor in the Warner Bros. feature Yankee Doodle Dandy; in the cartoon, the host announces Cagney as the victor off-camera, obviously recorded during one of Mel Blanc’s “pick-up” sessions months after.

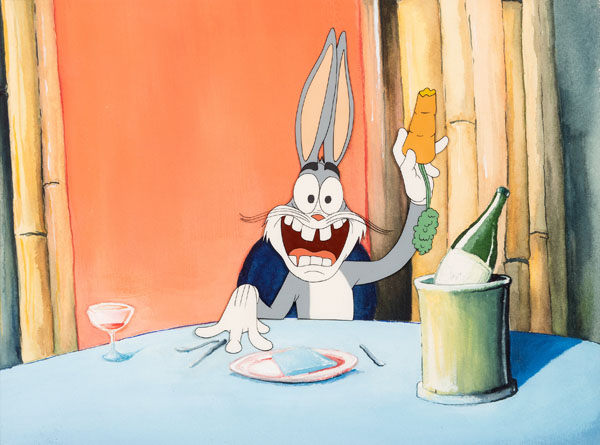

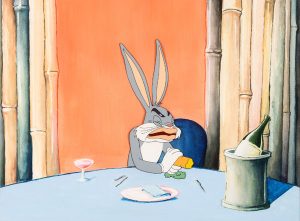

Nearly a decade earlier, Disney’s Mickey Mouse stood at the center of the Hollywood spotlight, surrounded by an adoring plethora of celebrities in attendance for the grand opening of the Mouse’s latest production at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Mickey’s Gala Premiere (1933). As originally storyboarded, after Robert C. Bruce asks the burning question, “Who will win the Oscar?” the rabbit reads a newspaper close to his face – or, as a handwritten note suggests, plays solitaire – before boastfully declaring he is” a cinch to win” the coveted Oscar. As animated by McKimson, Bugs is seated at a table, nonchalantly munching on a carrot, as if listening to the narrator’s inquisitive curiosity. No celebrities directly appear as they did in the earlier Disney film—instead, Bugs takes on their identifiable shapes, morphing into imitations of Katharine Hepburn, Edward G. Robinson, Jerry Colonna, and Bing Crosby. (Bugs also greets notable film director Cecil B. DeMille who is otherwise not imitated.)

Nearly a decade earlier, Disney’s Mickey Mouse stood at the center of the Hollywood spotlight, surrounded by an adoring plethora of celebrities in attendance for the grand opening of the Mouse’s latest production at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Mickey’s Gala Premiere (1933). As originally storyboarded, after Robert C. Bruce asks the burning question, “Who will win the Oscar?” the rabbit reads a newspaper close to his face – or, as a handwritten note suggests, plays solitaire – before boastfully declaring he is” a cinch to win” the coveted Oscar. As animated by McKimson, Bugs is seated at a table, nonchalantly munching on a carrot, as if listening to the narrator’s inquisitive curiosity. No celebrities directly appear as they did in the earlier Disney film—instead, Bugs takes on their identifiable shapes, morphing into imitations of Katharine Hepburn, Edward G. Robinson, Jerry Colonna, and Bing Crosby. (Bugs also greets notable film director Cecil B. DeMille who is otherwise not imitated.)

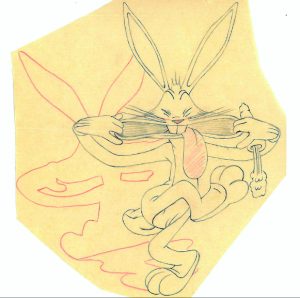

Like Felix showing off his range of expressions to Will H. Hays in Felix Goes Hollywood (1923), Bugs employs his acting expertise, transforming into different roles as the emcee announces the winner’s attributes before the award is granted. At the mention of dramatic parts, Bugs’ mimics the posture of a stereotypical melodramatic villain, twirling his whiskers like a handlebar mustache. Next, for his mastery of “refined comedy,” the rabbit stretches the corners of his mouth with his tongue extending out. Then, Bugs demonstrates his presence as a screen lover, transforming into Charles Boyer, intimately caressing his carrot as if it were his leading lady. Finally, the Academy host states the actor is adept in character roles, to which Bugs converts his body into Frankenstein’s monster. (This sequence also illustrates the cartoon’s rushed production; when Bugs enters the stage, his contact shadow wobbles, indicating an overlooked error from the in-betweening phase.)

Like Felix showing off his range of expressions to Will H. Hays in Felix Goes Hollywood (1923), Bugs employs his acting expertise, transforming into different roles as the emcee announces the winner’s attributes before the award is granted. At the mention of dramatic parts, Bugs’ mimics the posture of a stereotypical melodramatic villain, twirling his whiskers like a handlebar mustache. Next, for his mastery of “refined comedy,” the rabbit stretches the corners of his mouth with his tongue extending out. Then, Bugs demonstrates his presence as a screen lover, transforming into Charles Boyer, intimately caressing his carrot as if it were his leading lady. Finally, the Academy host states the actor is adept in character roles, to which Bugs converts his body into Frankenstein’s monster. (This sequence also illustrates the cartoon’s rushed production; when Bugs enters the stage, his contact shadow wobbles, indicating an overlooked error from the in-betweening phase.)

Outraged over the loss of the Best Actor award to James Cagney, Bugs Bunny proclaims the Academy’s decision as sabotage (pronounced in his New York patois as “sab-ah-TAH-gee”), a term recognizable to moviegoers relating to past and current attempts of enemy sabotage during both World Wars (the infamous 1916 “Black Tom” explosion in WWI, and the failed Operation Pastorius mission from German intelligence in 1942 are prime examples.)

Outraged over the loss of the Best Actor award to James Cagney, Bugs Bunny proclaims the Academy’s decision as sabotage (pronounced in his New York patois as “sab-ah-TAH-gee”), a term recognizable to moviegoers relating to past and current attempts of enemy sabotage during both World Wars (the infamous 1916 “Black Tom” explosion in WWI, and the failed Operation Pastorius mission from German intelligence in 1942 are prime examples.)

The production draft credits Bob McKimson and Rod Scribner for the scene, implying a switch between both animators within the same shot. Scribner animates Bugs sputtering after the winner is declared, then changes to McKimson when the rabbit commands the audience to hold their applause and Bugs’ plea to have the congregation reconsider their selection. When Bugs walks away from the camera to pull down a projector screen, holding several cans of film containing his “best scenes,” the animation reverts to Scribner’s. McKimson’s work resumes after Bugs tosses the reels over to the projectionist and notices the “stag reel” (slang for a pornographic film) running through the projector.

Bob Clampett and Mike Sasanoff seated at the table with the carrot juice bottle, photographed for animation reference.

The projection displays an excerpt from Friz Freleng’s aforementioned Oscar-nominated Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt (1941), featuring a more makeshift Bugs Bunny (in his fourth cartoon) than seen in the framing devices. In effect, using an earlier cartoon further minimized production costs for Schlesinger; such releases were known in the industry as “cheaters.” After the Hiawatha clip finishes, Bugs is more assertive in campaigning for the Oscar in a genuine electoral approach, beating a large drum and dispensing cigars to the spectators, as animated by Phil Monroe. Borrowing more from A Star is Born, Bugs’ request to the audience, “Do I get it or do I get it?” is an allusion to Frederic March’s drunken tirade at the prestigious event, demanding three statues for “Worst Actor”: “Do I get ‘em or do I get ‘em?”

Instead, the rabbit is pelted with fruits and vegetables, emerging from the mound as Carmen Miranda, adorned in a fruit hat (animated by Virgil Ross), inspired by her appearances and lavish musical numbers in 20th Century Fox films. Finally, Bugs is struck on the head by an award of recognition—an Academy Award in his image, labeled as a “Booby Prize Oscar” on its backside. Despite the derisive circumstances of the award, Bugs is honored to accept his token of recognition and intends to take his possession to bed with him every night. The “booby prize” is pleased with these words and plants a kiss on Bugs’ lips before striking an effeminate pose. (The prize’s response, “Do you mean it?” is lifted from Bert Gordon’s The Mad Russian character, notable on Eddie Cantor’s Texaco Town radio program.)

Production drawing courtesy of Paul Bussolini.

Before the “pick-up” sessions initiated on What’s Cookin’ Doc, the August 14, 1943 edition of Harrison’s Reports slated the announced release date for November 20. However, Technicolor processing delayed the release date to January 1st, 1944, in the trade magazine’s November 20 edition. Evidently, Clampett sought the advice of the Academy’s executive secretary Donald Glenhill for the subject matter of the cartoon. In a letter addressed to his wife, Margaret (later known as Margaret Herrick), dated December 7th, the studio received the first print from Technicolor. Clampett wrote to “Mrs. Donald Gledhill”: “Everyone that sees [What’s Cookin’ Doc?] feels it is the finest cartoon we have yet made, from the standpoint of originality and quality. In no way is the dignity of the Academy anything but complimented; and yet, there are many hearty laughs at the antics of BUGS BUNNY.”

A circulating newspaper story from December 22, 1943, described What’s Cookin’ Doc as “a travesty on Academy Award procedure,” reporting that the cartoon would be entered in the Academy Award competition this year. However, no records survive to determine if the cartoon was submitted or placed under consideration. What’s Cookin’ Doc was ultimately released in theaters a week past its expected date on January 8th, 1944, though a Nebraska newspaper mentions its showing in theaters weeks earlier on Christmas Eve. In New York, What’s Cookin’ Doc played at the Strand Theater from February 28 to March 6, accompanying the Warner Bros. feature In Our Time. In the weeks of March 20 to April 3, the cartoon played at the Globe Theater, billed with the Republic feature The Fighting Seabees.

A circulating newspaper story from December 22, 1943, described What’s Cookin’ Doc as “a travesty on Academy Award procedure,” reporting that the cartoon would be entered in the Academy Award competition this year. However, no records survive to determine if the cartoon was submitted or placed under consideration. What’s Cookin’ Doc was ultimately released in theaters a week past its expected date on January 8th, 1944, though a Nebraska newspaper mentions its showing in theaters weeks earlier on Christmas Eve. In New York, What’s Cookin’ Doc played at the Strand Theater from February 28 to March 6, accompanying the Warner Bros. feature In Our Time. In the weeks of March 20 to April 3, the cartoon played at the Globe Theater, billed with the Republic feature The Fighting Seabees.

In July 1944, five months after the general release of What’s Cookin’ Doc, Leon Schlesinger resigned as head of the animation department after selling his studio to Warner Bros. The Warners cartoons did not win an Oscar until a few years later, when the first Tweety and Sylvester pairing Tweetie Pie — an idea originated by Clampett and directed by Freleng—was voted the Best Cartoon Short of 1947.

As the studio progressed, secondary characters such as Pepe le Pew (For Scent-imental Reasons [1949]) and Speedy Gonzales (the titular Speedy Gonzales [1955]) each amassed an Academy Award. Yet, despite his acclaim as Warners’ top cartoon star, Bugs Bunny had not yet won the award. It was not until 1958, with Friz Freleng’s medieval-themed Knighty Knight Bugs (1958), that a Bugs cartoon received the honor of Best Animated Short Film. This was, perhaps, out of kindness from the Academy to honor the rabbit, 18 years after his screen debut. Now, with an award to his name, Bugs’ triumph was evident on his television program The Bugs Bunny Show, first aired in 1960, whenever announcer Dick Tufeld touted him as “that Oscar-winning rabbit.”

This month’s breakdown video includes Jerry Beck’s audio commentary from the recent blu ray set. If the embed below doesn’t work – Click Here.

(Thanks to Jerry Beck, Ruth Clampett, Michael Barrier, Yowp, Frank M. Young, Keith Scott, and Eric Costello for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

A wonderful piece of animation history, Devon. Congrats! is obvious that quality cartoon research is in very good hands with your good self. I am happy to help on future cartoon breakdowns if I can, and I really feel that a coffee-table book of these would be a marvelous thing to aim for. Cheers.

This is one of my favorite Bugs Bunny cartoons. It features some of Robert McKimson’s best animation of Bugs. What 20th Century Fox movie is that clip of the Cocanut Grove from?

Fabulous work Devon! The wealth of information you’ve stuffed into this piece is supremely commendable! I’m so happy I finally know where the live-action footage was taken from, the pick-up animators used in the final minute of the cartoon, and so so much more! Learning the topical references that flew over my head was great. Even stuff I wouldn’t have figured WERE topical like Bug’s “Do I get it or do I get it?” line. Great work as always Devon! Very deserving breakdown of probably the best “cheater” cartoon ever made. I eagerly await your next post!

Fascinating!

A superb post, Devon, my thanks to you and Ruthie for making the animator’s draft available.

This is indirectly from Bob Clampett himself, but supposedly the HIAWATHA’S RABBIT HUNT footage is Clampett taking a dig at Friz Freleng. The “joke” is that the new animation is some of the best ever done of Bugs Bunny (it was studio-wide accepted McKimson was the gold standard), while the old, Oscar-nominated footage (“my best scenes”) is the horsey looking stuff that the Freleng unit still hadn’t completely ironed out by the time WHAT’S COOKIN’, DOC? was made. Some sort of “punk” if you will. A paradox, as Clampett called HIAWATHA’S RABBIT HUNT “an excellent cartoon” in that historic 1969 interview with Mike Barrier and Milt Gray. (Personally I always thought the HIAWATHA footage made sense, not just because of the Oscar-nominee status, but because despite the weak drawing, but that the “bath” sequence is a superb bit of direction and writing from Friz and Mike Maltese.)

I know the golden rule right now is to paint Bob Clampett as the guy who never said a bad word about anybody, but that does a disservice to him as an artist: he had critical opinions and it makes him a much more fascinating figure.

The animation in two of the scenes used from ‘Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt’ are by Cal Dalton. The first shot of Hiawatha saying “..this pot right here…that’s just what I’m gonna do…” and the bath-tub boiling pot shot of Bugs slowly lowering himself in to the vessel, looks like Cal’s animation as well. He should have received credit in the draft!

Thanks to Devon for a terrific post and great “Cartoon Research”!

Most of it looks like Gil Turner’s animation to me, except for that last shot which seems to be either Manny Perez or Gerry Chiniquy.

Yo why the hate on Friz, Thad? At least he had a sense of *character*.

Excellent work as always, Devon! Looking forward to more of these Clampett breakdowns along with the rest of your quality work. I didn’t expect to learn this much from this particular short. Bravo!

Great research! One minor point: The Cocoanut Grove was not a hotel but a good-sized nightclub, located in a ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel.

Thanks Devon – and Ruth!

Great news about the draft finds, and upcoming breakdowns.

Roll ’em Smokey!

A “cheater” cartoon done right. With so little new animation done, I always thought McKimson was the sole animator, but Clampett made the best of his unit’s talents.

Looking forward to seeing more Clampett breakdowns. Hopefully some animators styles, such as Sutherland, can be pinned down.

There should be a bio on Clampett, not just of his career, but also some of his shenanigans. That would make a great read.

I don’t care if this is considered a cheater cartoon, it’s one of my favorites from Clampett. A big part of the appeal is Robert C. Bruce’s always enjoyable narration in the first couple minutes, but also when it gets to Bugs, the overconfidence that he’ll win makes the eventual “Our own, James Cagney!” all the funnier. Plus, the Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt clip they chose is both legitimately funny on its own but silly because it ends so abruptly and we get that great “THE END” pun.

I’ve said this before but the animation where Bugs goes through all the celebrity impressions is one of my favorite bits by Robert McKimson.

Such a prime example of “Cartoon Research” on one of the greats!

In a cartoon full of fun, somehow the animation of the reflective metallic look of Bugs’ Statue always struck me as just so *cool*, and so quintessentially *cartoony* in all its 3D rubbery shininess. (And I always assumed the “Do you mean it?” was a romantic french accent. Live and loin!)

Fine article, Devon!! Thank You.

The song played while Bugs gestures onstage awaiting “his” Oscar is, very appropriately “Ridin’ For A Fall”, sung by Jack Carson accompanied by Spike Jones and His Serious Orchestra in THANK YOUR LUCKY STARS (1943).

https://youtu.be/lGJzvgSInP8

Perfect! It’s fun when I recognize a musical “hidden message”, but that’s one of the many I didn’t know

Slight correction. It’s actually Dennis Morgan who sings ‘Ridin’ For a Fall’. Jack Carson is in ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’ but only for one of the specialty numbers (accompanied by Alan Hale, no less!)

For a considerable number of seconds when Bugs protests and addresses the audience, the flesh colored section of his ears have no black outline.

I’ve always been curious about the Clampett archive’s contents, so these upcoming posts will definitely scratch that itch. I’ve always enjoyed this cartoon, mainly because of that superb Robert McKimson character acting. And you just can’t go wrong with the classic “stag reel” gag! I look forward to your next Clampett archive posts, Devon.

Cartoon Research at its’ finest. Can’t wait for the future. Thanks Devon and Ruth.

Nice profile pic! That was peak Scribner right there.

The Oscars for Warner Bros. cartoons came too late and for the wrong ones. But often the awards represent a body of work rather than an individual achievement.

That’s been my view for years, since these guys essentially worked in a vacuum. FOR SCENT-IMENTAL REASONS may not be the best Jones cartoon of the year, the Freleng cartoons aren’t necessarily his very best; but the award stands as rare industry recognition for the art these guys were regularly making, against the odds of Disney pandering and Metro ballot stuffing. (I do think BIRDS ANONYMOUS, though, is one of the few cartoons in general that fully deserved its recognition.) Funnily enough, I was watching the footage of the 1955 ceremony the other night, and whatever your opinion on SPEEEDY GONZALES is, you have to love Friz (in lieu of Selzer out with an illness) walking up to accept the Oscar, grinning ear to ear.

Birds Anonymous is a tribute to Mel Blanc’s astounding versatility.I loved Sylvester’s break down because it didn’t feel “cartoony”, that was straight up tragedy.

It may not’ve been the best Bugs short, but I still consider it one of my favorite shorts with Sam.

KNIGHTY KNIGHT BUGS is a fine cartoon and probably the best of the post-shutdown cartoons with Sam. (The timing always felt a little suspicious… the ceremony was in early 1959, when The Bugs Bunny Show was in production… Almost as if the voters got a little emotionally strong-armed, since “that Oscar-winning rabbit” should’ve been a title Bugs had for YEARS at that point.)

I’d give the edge to Wild and Woolly Hare and From Hare to Heir in terms of post-shutdown Bugs/Sam shorts, but Knighty is a fine cartoon as well.

Yeah, but it’s really a straight-up remake as SAHARA HARE, and not quite as great.

Wow, thanks Devon and Ruth… This is what Cartoon Research is all about. Imagine!!! Phil Monroe and Virgil Ross were in on that fantastic Bugs Bunny animation!!

Great post. I’m hoping some of these sheets mentions some unrealized scenes in some cartoons.

I’ve long suspected that the “Stag Film” gag was a reference to what most likely went on “after hours” in the Termite Terrace projection room.

A good cartoon, if Bugs isn’t completely out of character here, as usual in Bob’s cartoons.

It’s weird – I’d never thought about that with this one, but I see what you mean. But somehow, his “loser” moments (like here and in Avery’s “Tortoise Beats Hare”) make his character seem more real to me, instead of less. Maybe I’ve known enough people who seem totally in control and smug — until you see their sore loser side at some unexpected moment.

Carl Barks was able to make Donald a very real kind of character in a similar way – like he could be a completely different duck on different days – but so believable when it’s all taken as a whole (as Mike Barrier has pointed out.)

For me, the definitive portrayal of Bugs Bunny was in Clampett’s cartoons. He seemed a lot more active, more human by being prone to outbursts, and simply far more humorous. The Jones Bugs could be entertaining but he was too reserved, too smug to be downright hilarious.