This week, we profile Disney/Warners animator Jack Bradburys vast career in comics!

Born in 1914 in Seattle, Washington, Jack Bradbury spent his entire childhood in his home state. He never received formal art training, despite drawing and cartooning during his school years. He graduated high school in 1932, during the depths of the Great Depression. To help support his family, he spent a year working odd jobs, such as thinning apples in Chelan, Washington, and sent part of his earnings back home.

After Bradbury heard of Walt Disneys studio recruiting new artists, along with a viewing of Three Little Pigs (1933) – a sensational film of its time – he wrote a letter and sent samples of wash drawings to the studio.

On September 6, 1934, Ben Sharpsteen wrote back to Bradbury, and offered a two-week trial period at the studio. However, he had to travel to Los Angeles under his own expense, so he borrowed 50 dollars from his grandfather and departed from Washington. He trained at Disneys as an in-betweener, and succeeded to a paid position at $15/week by November 5. He was promoted as an assistant animator to Bob Wickersham a few years later on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

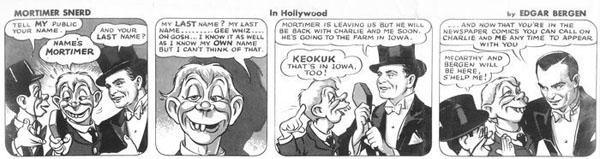

For a brief period, Bradbury had been offered a chance to draw a syndicated comic strip featuring popular ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his two dummies Charlie McCarthy and Mortimer Snerd. With Bergens approval, he drew a weeks worth of strips. Bradburys brother Ed drew backgrounds while Disney publicity artist Hank Porter performed inking duties. After two weeks, the syndicate postponed the Edgar Bergen strip, and Bradbury continued his work for Disney, becoming a full animator by 1938.

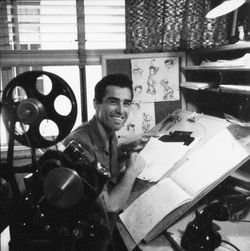

Jack Bradbury at Disney

Union organizer Herb Sorrell managed to procure jobs for the strikers to paint cargo ships in San Pedro and Long Beach harbors. Thus, Bradbury went into defense work for almost a year. While he worked at the shipyards, Bradbury was offered a job with MGMs animation studio, but turned it down. A month later, he received a call from Warners, and arranged a meeting with Friz Freleng shortly after. At first, Freleng offered him a job as a layout artist, but since Bradbury hadn’t any experience, he went into the studio as an animator.

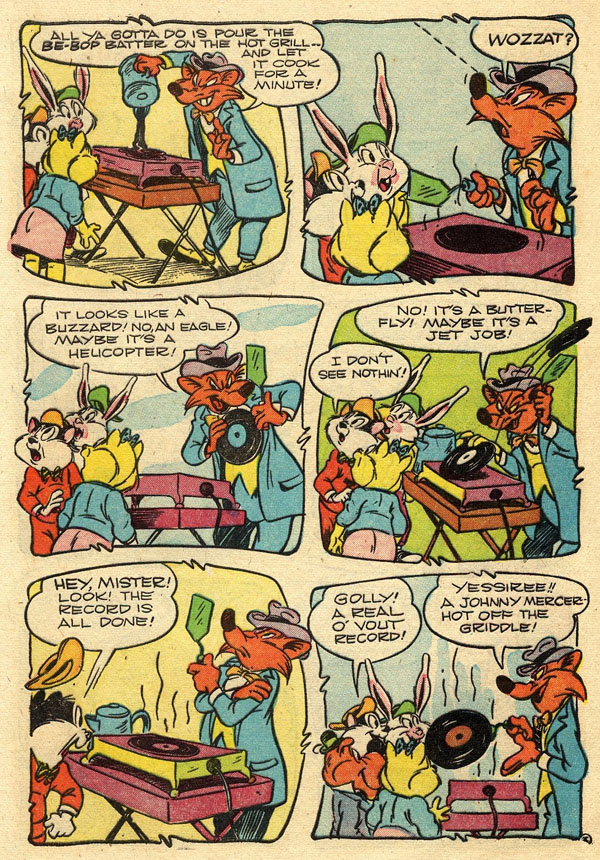

During his time at Warners, Bradbury became acquainted with James Davis through animator Gil Turner. After a meeting with Davis, Bradbury wrote and sketched his earliest comic book story, entitled Footsy Hare Gets the Drop on the Tortoise! (published in Giggle Comics #6, March 1944). Soon, he was animating at Warners during the day and drawing comic books for Davis in the evenings and weekends. He left Warners when Davis offered Bradbury a position at the small Carey-Weston studio, which produced training films, for a higher salary. After work on an animated segment for a live-action feature finished, Bradbury left to draw comics regularly.

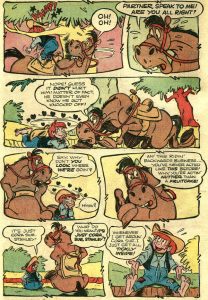

Sometime after World War II ended, Bradbury, Davis, and writer Hubie Karp decided to share an office together while other animators worked from home. Artist Al Hubbard joined them later after they re-located their spaces from Montrose to Glendale. In summer 1948, publisher Benjamin Sangor cut back on work from outside publishers, including Davis operation. Several months of hardship ensued, in which a short-lived comic run of his original characters Spunky, Junior Cowboy and Stanley the horse received poor sales. Afterwards, he tried his hand in selling gag cartoons to magazine publishers, but no one was interested.

Sometime after World War II ended, Bradbury, Davis, and writer Hubie Karp decided to share an office together while other animators worked from home. Artist Al Hubbard joined them later after they re-located their spaces from Montrose to Glendale. In summer 1948, publisher Benjamin Sangor cut back on work from outside publishers, including Davis operation. Several months of hardship ensued, in which a short-lived comic run of his original characters Spunky, Junior Cowboy and Stanley the horse received poor sales. Afterwards, he tried his hand in selling gag cartoons to magazine publishers, but no one was interested.

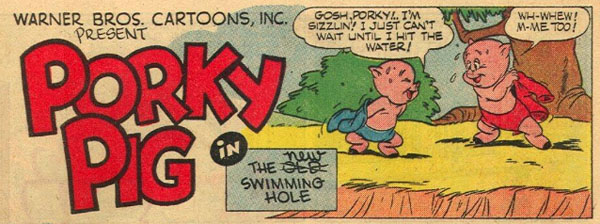

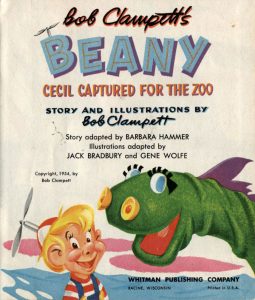

By 1949, Bradbury decided to work for Western Publishing. He took over the drawing duties of the featured Donald Duck stories usually drawn by Carl Barks starting with the February 1950 issue. Though he drew and inked his comics for Western, he wasnt permitted to write any of the stories, as he did for Davis. During his time at Western, Bradbury gradually adjusted to their methods, drawing coloring books and Golden Books, in addition to the comics. An exception to drawing Disney characters was at least two Porky Pig stories for different Four Color magazines. Another occurred when Bob Clampett, under the success of his new childrens television show Time for Beany, he signed a contract with Western which stipulated Bradbury would supply the artwork for each issue with Beany and Cecil in their entirety.

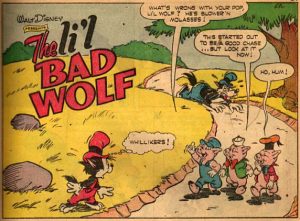

Throughout his time at Western, Bradbury drew many comic book stories with the Disney characters, including Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, Pluto, Chip n Dale, and Lil Bad Wolf, among others. By the early 60s, the stories he drew for Western were intended for the overseas market. (Two foreign Super Goof stories, drawn by Bradbury, have recently been reprinted and translated in two IDW volumes, here and here.)

Throughout his time at Western, Bradbury drew many comic book stories with the Disney characters, including Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, Pluto, Chip n Dale, and Lil Bad Wolf, among others. By the early 60s, the stories he drew for Western were intended for the overseas market. (Two foreign Super Goof stories, drawn by Bradbury, have recently been reprinted and translated in two IDW volumes, here and here.)

By 1969, Bradbury performed penciling duties on the comics, and left the inking to other artists, as his eyesight began to deteriorate. In 1978, he retired from cartooning, except for coloring books on occasion for Western. In the late 80s, ACE Comics published a new version of Spencer Spook, a ghost character from the 40s Sangor comics, with scripts by Bradbury and drawings by Dave Bennett. He passed away in 2004 at the age of 89.

To learn more about Bradburys career, his son created a website dedicated to his fathers work in comics. It includes excerpts from an autobiography written by Bradbury, where he details his career from its beginnings to his time at Western Publishing. His entire comic work for James Davis shop is also presented, as well, compiled by Dave Bennett.

Now that Im able to supply the Sangor stories on a separate page, here is a sampling of Bradburys stories for Western Publishing:

The New Swimming Hole (Porky Pig) Four Color #295 (September 1950)

The Blue Man (Beany and Cecil) Four Color #414 (August 1952)

Family Tree (Donald Duck) Donald Duck #30 (July-August 1953) written by Carl Fallberg.

Fountain of Youth (Lil Bad Wolf) Walt Disneys Christmas Parade #6 (November 1954)

Ninety-Day Wonder Mickey Mouse #47 (April-May 1956)

Forest Vigilantes (Chip n Dale) Chip n Dale #6 (June-August 1956)

Dangerous Diggings (Pluto) Four Color #941 (October 1958) written by Don Christensen.

(Thanks to Dave Bennett, Didier Ghez and Michael Barrier for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

I like Bradbury’s art and this post certainly offers a very generous helping of it, even if most of his Disney-related comics work is off limits. I have some of those “Spunky” comics — the little cowboy with an apparent aversion to footwear — among what I inherited from my dad

It always throws me how Dishonest John is drawn in these 1950s Beany and Cecil comics. I suppose it’s because I was raised on how he looked in the animated cartoons, with his nose and chin much longer and more exaggerated. That was one of the problems my dad had with the Beany and Cecil cartoons. He was raised on the puppet show and regarded the cartoon series as a poor imitation of the “real” Beany and Cecil, anyway, but on top of that it really annoyed him that characters like D.J. didn’t look right to him. That is, didn’t look the way the had on the puppet show and in the 1950s comics.

One character that Bradbury helped developed at Disney was the sinister Dr. Emil Eagle. When he debut, he was as tall as Gyro Gearloose and has hair. However, in subsequent appearances, starting in some stories drawn by Tony Strobl, he was bald and short. Personally, I thought he looked better tall, but it seems artist today like him short. To date, Emil has not made any noble appearances in animation.

I should also point out that the hyperlink for “Ninety-Day Wonder” links to “Dangerous Diggings” instead.

Fixed!