Today, we look into one of Hugh Harman’s lavish MGM cartoons!

Harman’s body of work distributed by a major live-action film studio exemplified his desire to compete with Disney’s cartoons. Harman evidently resented the successful producer after working for him during the silent era. Like Disney, he shared a perfectionist tendency, dedicating more time on the stories and a definite assurance of elaborate animation. As an employee for MGM’s new animation studio (established after they terminated their agreement in producing solely for Harman and associate Rudy Ising on February 1937), he continued to vex producers with increasingly high budgets on his last few cartoons. Putting into perspective Harman’s need for precision, The Field Mouse’s budget nearly rose to $35,000 – whereas Paramount set a ceiling price of $30,000 on the Fleischer’s rising Superman series. Harman didn’t care, as long as MGM supplied the money.

The “morality films” Harman produced and directed during the early ‘40s often have a solemn tone. An elderly squirrel, in the acclaimed but aggressive Peace on Earth (1939), tells his two grandchildren of a land once ravaged by trench warfare. The destruction leads to cute forest animals building and dwelling within their own village, repurposing the belongings of fallen soldiers. Harman’s belief in preserving childhood innocence, in cartoons such as this is endearing, but seem more instructive on the surface.The near-sighted protagonist of The Little Mole believes a garbage dump is a “fairy palace” until a pair of glasses, given him by a con man, proves differently. When his glasses break, later in the film, and he comes close to drowning, he accepts the fantasy as it stands. The little rabbit willing to accept a vicious predator as a friend — though oblivious to his starvation — in The Hungry Wolf, offers another component of Harman’s penchant for poignancy.

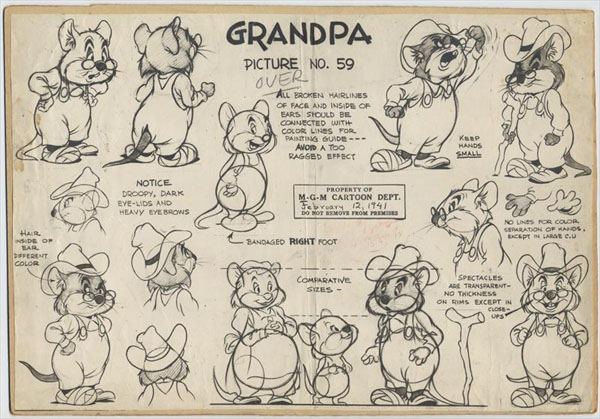

The Field Mouse attempts to show the consequences of shirking responsibilities, but fails to redeem itself by the end. Herman, the main character, sleeps underneath a sunflower, and ignores his mother and grandfather’s insistence on working before he hears the impending approach of a wheat thresher. The film’s stated ethics are discarded to focus on the peril of Herman and his grandfather inside the hazardous machine. The grandfather’s personality takes a sporadic shift from tender to cantankerous when the family is forced to evacuate (with the line “You can’t do this to me!” repeated to annoyance).

Despite its narrative flaws, The Field Mouse abounds with detail, particularly in the elaborate inner workings of the wheat thresher, as designed by layout artist Joseph Smith. A Rainy Day with the Bear Family, released a year earlier, climaxes as Papa Bear faces ocean waves of roof shingles during a thunderstorm. Harman decided to return to this visual in The Field Mouse, as Herman and his grandfather swim against a waterfall of grain. This theme of diminutive characters risking their lives against large mechanisms is strikingly similar to little Swee’ Pea’s perils inside the factory in the 1937 Popeye cartoon Lost and Foundry. The theme was echoed in 2000, with the chicken pie machine in Nick Park’s stop-motion feature Chicken Run. These three examples use intricately detailed machinery to provide a threat for their characters, and each sequence reflects advances in technology.

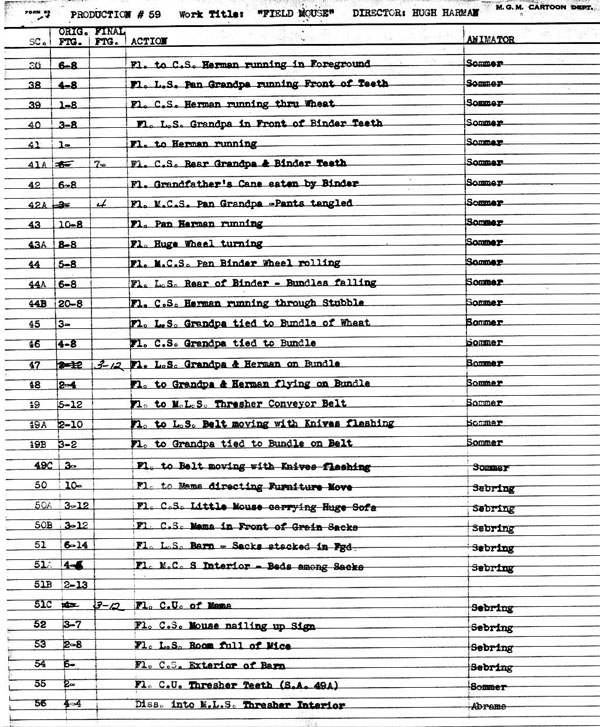

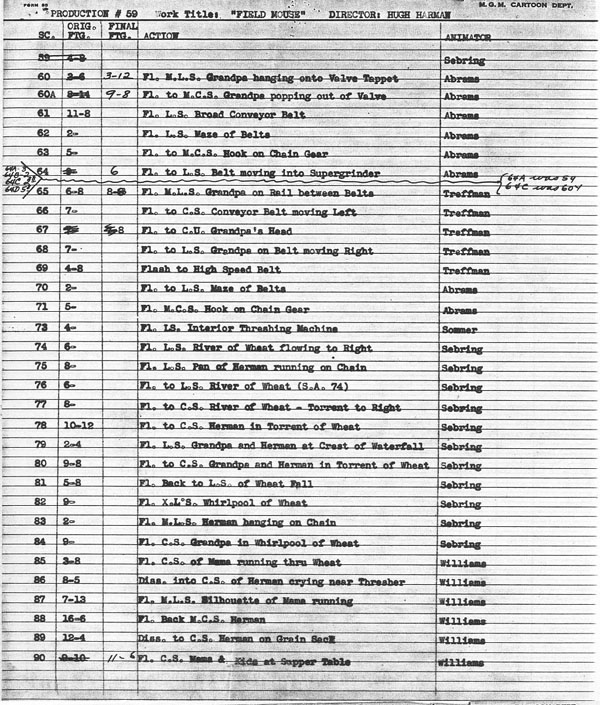

Many of the key animators on Field Mouse are assigned large blocks of sequences. Don Williams animates up to three minutes of the cartoon, including the opening sequences and the key acting scenes with Herman and the two principal family members. His tendency to draw blocky-looking characters seen in his later work at Lantz and Warners, emerged at MGM. Leonard Sebring handles the scenes of the grandfather stubbornly remaining behind the family, along with their fight for survival against the waterfall of wheat. Sebring previously worked at Disney during the ‘30s, and would leave MGM (and animation) altogether. He returned to his Kansas hometown, where he worked on advertising projects for local companies.

Paul Sommer animates an extended sequence where Herman leaves his family behind to rescue his grandfather. It’s unclear if Sommer, or a specialized effects artist, handled the difficult animation of the thresher, but his credit remains on the video. Sommer animated for MGM when it established its own studio in 1937. He became a director for Screen Gems in the ‘40s. After a stint at Terrytoons, Sommer migrated back West to Hanna-Barbera, as a story director and layout artist.

Little is known about animator David Treffman, who is assigned a small amount of footage. He worked at the Mintz studio in the early ‘30s, as documented by a staff photo supplied by Mike Barrier. He is credited on the draft for The Flying Bear, a 1941 Barney Bear entry, with an available document that is unfortunately incomplete.

Irv Spence and Ray Abrams handle brief sequences. Spence’s broad animation/posing of the lazy Herman being scolded is wonderful. Ray Abrams animates an interesting low angle shot in scene 25, as the house shakes from the rumbling thresher in his usual rubbery fashion. You’ll notice that scenes 69-71, though listed on the draft for Field Mouse (the last two shots credited to Abrams) do not appear in the final cartoon. Quick cuts, designated by letters, were added to scene 64 (also animated by Abrams), presumably to strengthen the drama of the peril.

By the time this cartoon reached theaters on December 1941, Harman had been gone from MGM for eight months, and formed his own studio. The presumptuous Harman had ambitious plans for an animated feature based on the legend of King Arthur. Enthusiastic to launch this venture, surviving story treatments and planned song sequences would be completed within the same month.

According to Mark Kausler, a good friend of Harman’s, the director seemed uninterested in his cartoons in later years, except maybe Peace on Earth. See what you think of this cartoon with this week’s breakdown video.

(Thanks to Michael Barrier, Mark Kausler, Frank Young and Yowp for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Even though this cartoon is a bit scattershot, narratively speaking, and undermines its supposed moral for the sake of a happy ending, I’ve always enjoyed it for its excellent artistry; the design and animation are top notch, and some of the individual sequences are genuinely enthralling. Thanks for providing this glimpse into its making! (And here’s hoping for a similar article for “Tom Turkey and His Harmonica Humdingers”…)

Harmon’s later MGM cartoons have some incredibly impressive visual stagings and animation, but the effort almost never justified the payoff to the cartoon, especially when subject to multiple viewings on television where the story has to be strong, no matter how beautiful the ‘look’ of the cartoon might be (it’s also amazing how deftly Warner Bros. used Mel Blanc’s vocals and how perpetually misused they were at Metro, where the goal always seemed to be to get Mel to sound as annoying as possible to the audience).

Yeah, Mel didn’t really get to shine at Metro at all.

Having saw these as a kid in the 80’s on TV, Harman’s films always came off slightly odd in it’s premises yet lavished in the artistry they were shooting for. These earlier Harman and Ising works were always mixed in with Tom & Jerry and Tex’s output in the TV packages so a cartoon like “The Field Mouse” got good exposure even though comparing this to what followed in the ensuing years is an overstatement. As a kid, I probably didn’t think much of the morals that were dished out on this, and seeing it again as an adult, it does seem slipshod towards the end. Perhaps not a great cartoon, but certainly not a bad one action-wise.

I’m still thinking of “The Little Mole” personally, and trying to stop myself from thinking the actual moral of that story was to ‘stay ignorant’.

Didn’t shine? What about “Peace on Earth”? I consider that to be one of Mel’s highlights.

Yeah I don’t want to fault that one Nic, but remember this was still back when Mel was getting to voice around town and had yet to be tied down to one studio later on.

Cartoon characters getting caught up in gears off outsized factory machinery is directly influenced from Charlie Chaplin’s MODERN TIMES (1936),

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tfw0KapQ3qw

‘Pat’ Ventura

http://www.patcartoons.blogspot.com/

Thanks Pat, you’re always welcome here!

There’s also a couple of nods to John Ford’s 1940 film of THE GRAPES OF WRATH.

My mom always says that the tractor scene in Secret of NIMH reminded her of this cartoon.

I’m sure plenty made the same observation Ian. If only Herman thought to try getting inside the engine and cut the fuel line. 🙂

Okay, I may be in the minority, but this was always one of my favorites! The odd disconnect between the obvious set-up on the front end (‘oh, I see, Grasshopper and the Ants, right?’) with a totally different plot thread in the second half always seemed to be a plus to me. It’s as if they figured out halfway through that nobody cares if Herman is lazy or not, and they just plowed ahead with the exciting stuff! And one of the few MGMs of this period that actually sustain the extra length (some those things push eleven minutes!)

It is a guilty pleasure to get a cartoon once in a while that didn’t stick to the 7 minute limit if they could find a way to stretch it just a bit.

I’m going to assume that the main reason Harman’s theatrical ambitions did not pay off way because he formed his production company shortly before the US entered the war. During the war years, there was not nearly as much free spending on lavish cinematic ventures as there was in the pre-war years. Perhaps sticking with it at MGM ’till the war was over before making the leap would have given him a better chance to launch into features.

That is a big ‘What-if” for me. What if he did stick around a few more years, let alone, would Tex had gotten somewhere at all had he not came to MGM in Hugh’s absence?

It’s interesting that you mention the budgets for MGM cartoons as “vexing” to MGM; kinda puts a different spin on cartoons of the HAPPY HARMONIES era, like “CIRCUS DAZE” where the escaped and menacing flea circus which drives just about every act within the carnival (save, ironically, for the shapely dancing girl) absolutely buggy becomes so large that it looks to any viewer on a TV screen like the “snow” interference that the TV’s of old used to get at times. There are so many cartoons of both periods where Harman piled on the action or detail to extremes. Yet, in so many of those cartoons, to me, there were other aspects that worked. I felt that “CIRCUS DAZE” was the best use of the often used piece called “The Poet and the Peasant” I’d ever seen. It would be used in a CAPTAIN AND THE KIDS cartoon and not nearly as well, and as the flea circus got bigger and bigger, the action got almost chlostrophobically chaotic. It is a shame, with skills like Harman’s, that a deal couldn’t be set for an animated feature film coming from MGM. They certainly had the talent throughout MGM to lend a hand or a voice! I don’t know why it never occurred to anyone.

And, despite Mel Blanc not really being given terrific material to work with at the other studios before Warner Brothers, he was the hardest working voice over in Hollywood at that time. He seemed to be everywhere. He did all he could to make the characters he was given as engaging as possible, and he is all over cartoons like “WANTED: NO MASTER”, the second of two Milt Gross cartoons. Needless to say, thanks for a breakdown of this Harman classic. I, too, would have liked to see Harman succeed in his goals, but he always ended up being relegated to these cherubic little characters. To me, his MGM Bosko cartoons succeeded only in giving me a lot to look at, and on the small screen, those images were very, very busy–I needed more than one viewing to pick up on the details on corners of the screen, unless cartoons like “CIRCUS DAZE” were given the pan and scan treatment that some theatrical cartoons got for whatever reason. I always wanted to see more of them on the big screen before I lost my vision, but anyway, I hope more of you someday get to see some of the wilder Harman efforts in that fashion real soon, even if through private collectors. Thanks for posts like this, though.

It was MGM first wartime cartoon.

The mother mouse really acted so ruraly.Looking very atractive good when dat she mother was working at the bed setting. Original mothers only get a xxl back view as this mousy moo got. she also made that in to the largest in size that same to my own ammies one. And she just show the real house mothers habits of bodies.. As being

the best, she do punis her lazy boy caching and throwing down to her round large lappy area. then she used my most favourite way to teach lesson her lazy boy on bed for late in

. my mom could do same to me n she did many many. but she had not that long sharp tail behind for me to use. so once she do altered by sewing a long black male cow tail to her under wears inside hiding. and that shown to me when she been angry. she do shunting me by that tail that on the round under my black big ugly naughties assy rose backey.

I could feel the ladies the way the manly motherings shame for rosy red susI.

.

I’m making my way through all the MGM cartoons chronologically and I’m at 1940.

These MGM have so many virtues and some absolutely superb works. Harman deserves far more praise and a real re-evaluation. Aside from raising their animation standards to the levels of the best of the other studios, and setting the stage from the start for Hannah/Barbera and Tex Avery to comes out of the traps firing on all cylinders, they had some superb cartoons, ‘Art Gallery’ in 1939 and 1940’s ‘The Lonesome Stranger’. Alas, I think that his association with Ising, who’s work was far too cute and aped of Disney for too long, overshadows Harman’s work. Just an observation.