Things are looking a little cuckoo with this week’s breakdown!

As you can see, this month of December isn’t entirely holiday-themed as last year’s. I hadn’t planned on it, either—I was lucky to have as many available drafts that fit the season. However, there is one particular Christmas-related special that I’m saving for the right moment.

As a director, story—and logic—were never big on Dick Lundy’s agenda. Among the most graceful of Disney’s classic animators, Lundy clearly loved his art form. Flowing, thoughtful animation captivated him, and there is a sense of indulgence towards his artists in these Lantz cartoons. He brought out the best in Lantz’s native animators, and he obviously pushed them to these heights of expression. When he temporarily inherited Disney stalwarts such as Fred Moore, Ken O’Brien and Ed Love, in the last few Lantz cartoons he directed (as previously profiled in Woody the Giant Killer, Wet Blanket Policy and Playful Pelican), Lundy realized an ideally lush, nuanced flow to his films.

As a director, story—and logic—were never big on Dick Lundy’s agenda. Among the most graceful of Disney’s classic animators, Lundy clearly loved his art form. Flowing, thoughtful animation captivated him, and there is a sense of indulgence towards his artists in these Lantz cartoons. He brought out the best in Lantz’s native animators, and he obviously pushed them to these heights of expression. When he temporarily inherited Disney stalwarts such as Fred Moore, Ken O’Brien and Ed Love, in the last few Lantz cartoons he directed (as previously profiled in Woody the Giant Killer, Wet Blanket Policy and Playful Pelican), Lundy realized an ideally lush, nuanced flow to his films.

When Lundy had solid story material—as in 1946’s Bathing Buddies, or the Oscar-nominated Musical Moments from Chopin—the results were delightful. Often, Lundy’s Lantz cartoons are full of irregular moments in which gaping story flaws overcome their lovely, subtle animation. The Coo Coo Bird is more of a set piece for Woody’s manic frustration, over a sleepless night, carrying out much of its situations and frustration comedy much like a Donald Duck cartoon. Another Lundy-directed title, Solid Ivory, is similar in treatment to Woody’s character. The narrative has nowhere to go, and its ending—best suited to a 1940s Columbia Screen Gems cartoon (though Disney used it in the an early 1929 Mickey Mouse, The Plow Boy)—is a real head-scratcher.

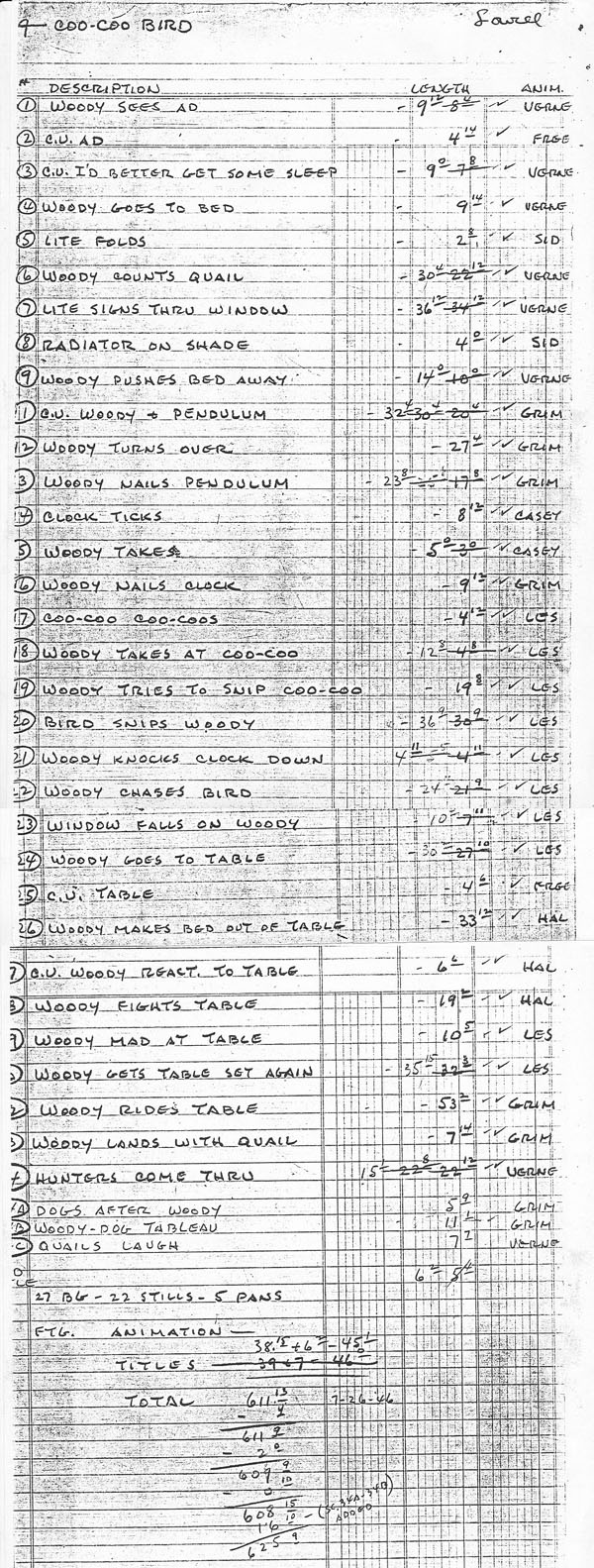

Lundy casts his animators on this film with extended sequences that amply display their talents—Verne Harding animates the opening scenes of Woody reading the advertisement detailing the start of quail hunting season, getting ready for bed and being awakened by a flashing sign. Grim Natwick animates the following scenes—displaying a volatile lunacy compared to Harding’s solid drawing/animation—of Woody annoyed by the ticking sound from a pendulum. Natwick later handles the scenes of Woody being attacked by his folding table, which sends him outside, where he’s chased by hunting dogs.

Lundy casts his animators on this film with extended sequences that amply display their talents—Verne Harding animates the opening scenes of Woody reading the advertisement detailing the start of quail hunting season, getting ready for bed and being awakened by a flashing sign. Grim Natwick animates the following scenes—displaying a volatile lunacy compared to Harding’s solid drawing/animation—of Woody annoyed by the ticking sound from a pendulum. Natwick later handles the scenes of Woody being attacked by his folding table, which sends him outside, where he’s chased by hunting dogs.

Hal Mason isn’t given as much footage as the other three animators, though he is credited in the main titles. Mason handles Woody fashioning his folding table as a bed, after which Les Kline takes over the middle portions of the sequence. Les Kline animates a large sequence with Woody trying to silence a cuckoo bird—in some of his finest work for Lantz. A standout moment in Kline’s career is scene 22, where Woody tries to smash the cuckoo with a bedpost. Kline has the characters move from foreground to background. These methods occur again in scene 30, as Woody angrily constructs his folding table-turned bed. There is some subtlety in Kline’s scenes, as well—in scene 24, Woody drags his blanket over to the folding table. As he mutters to himself, he nearly trips on his blanket before catching himself.

December 1928 illustration signed by “Lester Kline.

Les Kline was formerly a commercial artist before becoming one of Lantz’s first animators, hired around mid-April 1929. He spent a vast majority of his animation career at the studio—even serving as a director for a brief period—and stayed until the studio closed down in 1948. Kline returned to Lantz in the mid-‘50s, after working on several animated commercials, and continued to animate until 1971, a year before the studio closed its doors, indefinitely. Though Sid Pillet is credited in the opening titles, he is only credited for two shots in the draft.

The date noted on the draft, written next to the calculations of total animation footage—July 26, 1946—presumably could’ve been when scenes was assigned to the animators. In a sense, it provides an insight into the production schedule/backlog of the Lantz cartoons; the film was released almost a year later, on June 9, 1947.

This will be the last Walter Lantz breakdown for a while, since there are no more drafts available to me at the moment. These drafts are all sourced from Mark Kausler’s collection, and I’d like to thank him for lending these materials. Three other Lantz titles, The Pied Piper of Basin Street, Wacky-Bye Baby and The Bandmaster, have already been analyzed in Mark Mayerson’s blog, so breakdown videos/drafts wouldn’t be necessary for this column. Looking more into Lantz documents, there are several “scene/footage sheets” housed in the UCLA Walter Lantz Archives, but, naturally, it isn’t as easy to obtain them. Time will tell, readers…

For now, enjoy!

(Thanks to Mark Kausler and Frank Young for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

What’s interesting about Lundy and his story crew is, toward the end, he was using Heck Allen. He and Allen also worked together a year or so later at MGM. Their Barney Bear cartoons have more energy than their Woody cartoons and I don’t understand why. Woody was supposed to be an aggressive character and you’d think that would result in a quicker-paced cartoon with harder gags.

Lundy was hamstrung when it came to using gag dialogue as Bugs Hardaway had about as much expression in his voice as the Google Narrator mode.

Likely because the MGM guys had been working for years on Tom and Jerry or for Tex, so they were already at a speed the animators he worked with at Lantz weren’t (save Ed Love). (Although Lundy repeated the same sort of miscasting seen here with Caballero Droopy, in which Droopy drops his nonchalant and non-reactionary nature to poor effect.)

Sorry, but Ben “Bugs” Hardaway’s “google narrator” voice had more personality and character than Grace Stafford’s girly voice, that she had given Woody throughout the 50-70s…

Late 40s Lantz cartoons under Lundy were at their most elegant, but at the same time they seemed to run into a bit of a wall at how to use Woody. That’s why it was great for the character that the studio came up with Buzz Buzzard a short time later (and sad that the studio had to shut down and then cut budgets a short time after that). As with Bugs over at Warners, Woody as the foil just doesn’t work as well as Woody the aggressive heckler, and the studio finally got a formula in Lundy’s final Woody shorts where the heckling could be channeled to its best comedic use.