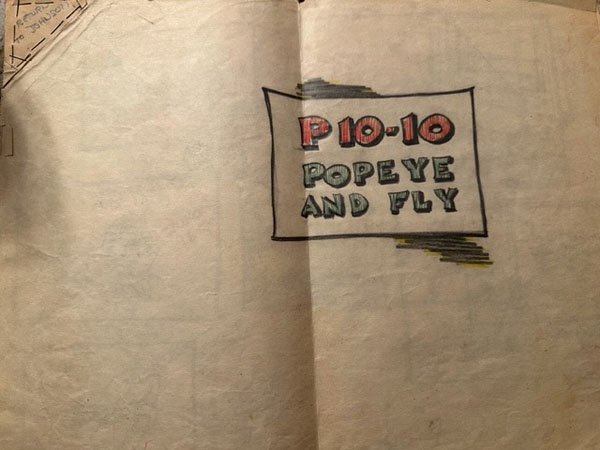

A surprise for Cartoon Research – an animator breakdown of a B&W Fleischer Popeye cartoon! Tom Johnson’s nephew, Andy Chance, was kind enough to lend the “director’s board,” which his uncle saved for decades.

A surprise for Cartoon Research – an animator breakdown of a B&W Fleischer Popeye cartoon! Tom Johnson’s nephew, Andy Chance, was kind enough to lend the “director’s board,” which his uncle saved for decades.

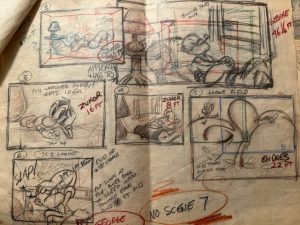

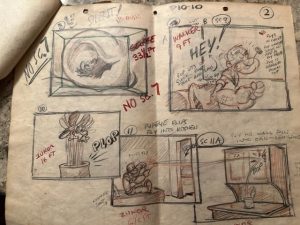

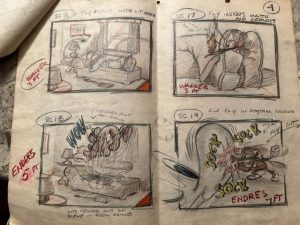

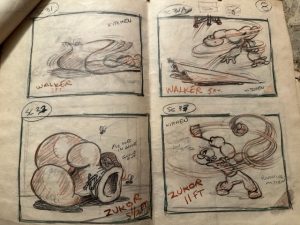

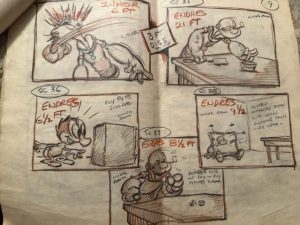

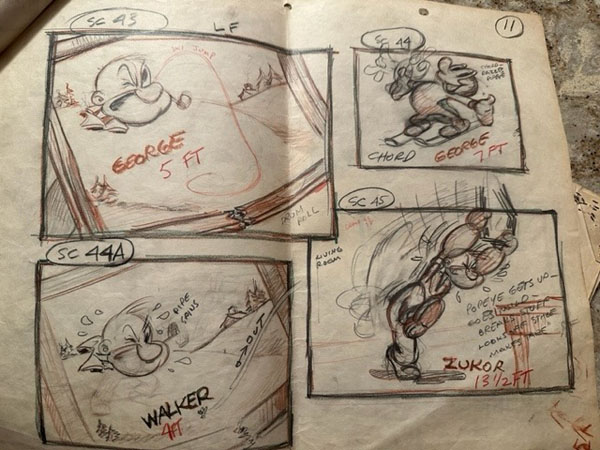

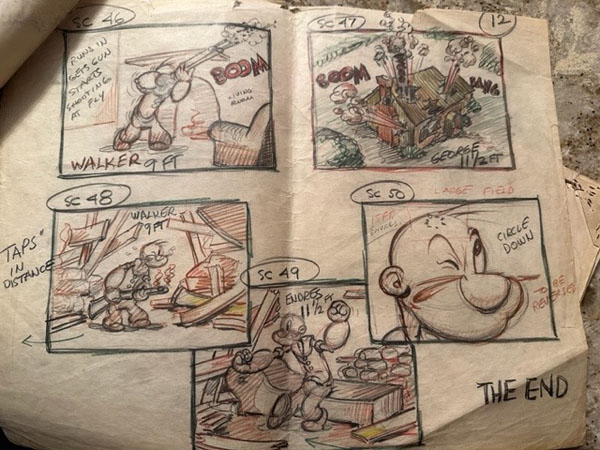

A “director’s board,” a working copy of the storyboard for Tom Johnson’s unit, contains thumbnail drawings reflecting the production storyboard, which was drawn in a different size. The director boards also demonstrate how Fleischer’s head animators (directors) planned and kept track of the animator assignments, footage, music tempo, and status of his sections.

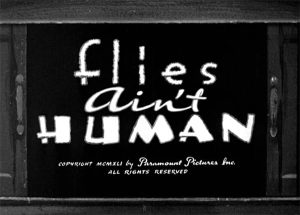

Although Max Fleischer’s principal artists collaborated with a mixture of writers and animators from the West Coast in sunny Miami, their influence on the Fleischer product inarguably led to the cartoons’ sharp decline in quality, especially on Popeye the Sailor. In this cartoon, Popeye is continuously annoyed and outsmarted by a housefly—a comic situation more suited for a generic character than Paramount’s leading animated star. Furthermore, Popeye uses a shotgun to solve his problem during the climax rather than eating his spinach; instead, the fly consumes it halfway into the film.

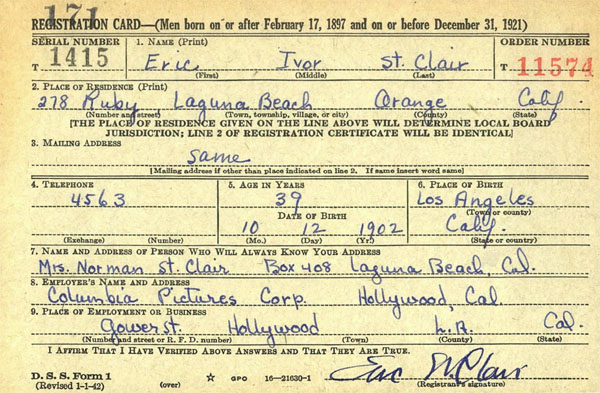

Eric St. Clair (1902-1968) is credited on the story for Flies Ain’t Human, his only screen credit for Max Fleischer. Some of Eric’s family members shared artistic backgrounds: Eric’s father, Norman St. Clair, was a notable architect and watercolor artist in Laguna Beach, helping establish the coastal city as an artists’ colony. His brother, Mal St. Clair, worked as a newspaper cartoonist but chose a career in live-action comedy shorts; Mal St. Clair first worked as an actor, writer, and director for Mack Sennett, co-directed two of Buster Keaton’s independent shorts The Goat (1921) and The Blacksmith (1922), and helmed four Laurel and Hardy vehicles released by 20th Century Fox in the early 1940s. (Incidentally, Eric was the male lead in a feature directed by his brother, Find Your Man [1924], starring Rin Tin Tin.) Meanwhile, in the early 1930s, Eric became an illustrator and painter at Laguna Beach, relocating to Miami by 1935. He joined Max Fleischer’s studio by the summer of 1939; his contributions before Flies Ain’t Human are unknown.

Eric St. Clair (1902-1968) is credited on the story for Flies Ain’t Human, his only screen credit for Max Fleischer. Some of Eric’s family members shared artistic backgrounds: Eric’s father, Norman St. Clair, was a notable architect and watercolor artist in Laguna Beach, helping establish the coastal city as an artists’ colony. His brother, Mal St. Clair, worked as a newspaper cartoonist but chose a career in live-action comedy shorts; Mal St. Clair first worked as an actor, writer, and director for Mack Sennett, co-directed two of Buster Keaton’s independent shorts The Goat (1921) and The Blacksmith (1922), and helmed four Laurel and Hardy vehicles released by 20th Century Fox in the early 1940s. (Incidentally, Eric was the male lead in a feature directed by his brother, Find Your Man [1924], starring Rin Tin Tin.) Meanwhile, in the early 1930s, Eric became an illustrator and painter at Laguna Beach, relocating to Miami by 1935. He joined Max Fleischer’s studio by the summer of 1939; his contributions before Flies Ain’t Human are unknown.

Eric’s draft registration card, dated February 14, 1942, affirms that he had settled back to Laguna Beach and found a job at Columbia Pictures.

Besides Tom Johnson’s regular animators, George Germanetti, Frank Endres, and Harold Walker, Lou Zukor (1912-2004) also worked on the short. Zukor was one of many animation artists who flocked to Fleischer’s Miami studio from the West Coast, where Lou had prior experience working for Romer Grey, Charles Mintz, and Walter Lantz during the 1930s. At Fleischer, Zukor primarily worked in Orestes Calpini’s unit (his only Fleischer credit is on Nurse Mates [1940]). The director boards presented here reveal that he shifted to Tom Johnson’s unit. (Note, too, that Zukor draws Popeye with black pupils when the director’s board for Lou’s scenes insists otherwise.)

Flies Ain’t Human had its announced release on April 4, 1941. Later, the Popeye cartoon played in New York’s Paramount Theater during the week of June 21, along with the feature One Night in Lisbon, starring Fred MacMurray, Madeleine Carroll, and Patricia Morison. Then, Flies had a repeat booking at the Rialto on the week of October 11, with the Universal motion picture Flying Cadets as the feature presentation. Years later, at Famous Studios, Tom Johnson supervised a remake, The Fly’s Last Flight, released in 1949.

Here are the “director’s boards” – Click on the thumbnails to enlarge.

Thanks to Andy Chance for the production materials and to Michael Barrier, Mark Kausler, Mark Mayerson, Harvey Deneroff, and Bob Jaques for additional information.

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Thanks for sharing this director’s board with us; we’re very lucky that it still exists after over 80 years. That said, I’m afraid I have to admit that “Flies Ain’t Human” is probably my least favourite Fleischer cartoon that doesn’t have any donkeys in it. I’ve always had a strong dislike for cartoons where somebody just wants to get to sleep but is continually prevented from doing so — and there are a fair few in this genre. About ten years later, Popeye would endure a similar situation in “Shuteye Popeye”, this time with a mouse who obtains super strength after being trapped in a can with some scraps of spinach left in it.

I don’t suppose eating spinach would have helped Popeye defeat the fly, any more than it would have inoculated him against measles or polio. As we all learned from the cheater “Adventures of Popeye”, spinach enables a little guy to overcome a big bully, and in other circumstances it can enhance one’s musical or dancing ability as well. Popeye had the right idea when he trapped the fly in his corncob pipe. Nicotine is a natural insecticide.

Poor Tom Johnson seems to have gotten stuck with the dregs of the studio’s output during its Miami period. What with Seymour Kneitel allocated to features, Myron Waldman doing the last of the Color Classics, and Willard Bowsky away in the army, Johnson was saddled with the Stone Age cartoons, the Animated Antics, the subpar Boops and the worst of the Popeyes. Then there was Johnson’s greatest creation, Wiffle Piffle, who never attained stardom in spite of the studio’s high hopes for the character. But by this time there was precious little that Johnson, or anyone else, could have done to reverse the sad decline of the Fleischer studio in its final years.

Was Louis Zukor related to Adolph Zukor, the “big cheese” at Paramount? That’s something I’ve wondered about for years! The late Gordon Sheehan told me that he considered George Germanetti to be one of the best POPEYE animators in the studio.

Paul, I don’t know if I’d consider FLIES AIN’T HUMAN to be one of the worst Fleischer POPEYE cartoons. I’m sue I could pick a few other ones instead. Gordon Sheehan also told me that Tom Johnson’s animation unit got the lesser screen assignments and stories – after head animators (directors) Willard Bowsky, Dave Tendler, Myron Waldman, etc. got their picks.

Interesting that Eric St. Clair was related to comedy director Mal St. Clair. I really dislike his work in the LAUREL AND HARDY films for 20th Century-Fox, but overall, he was a decent comedy director and I’m sure he learned a lot from working with Buster Keaton!

Lou Zukor wasn’t related to Adolph, but I’m sure he got teased a lot when he was with Fleischer. “Zukor” is a Hungarian variant of Zucker, the German word for “sugar”, which is a common Jewish surname. Adolph Zukor was actually born “Czukor”, but he dropped the first letter when he came to America as a teenager; while, conversely, the father of director George Cukor (also no relation) dropped the second letter from the same original surname.

Devon, I forgot to say that you do a great job in “breaking-down” who did what in some of our favorite cartoons. I’m glad that you located some artwork for perhaps a lesser POPEYE Fleischer cartoon, but it’s the first one I’ve seen yet! Many years ago, Gordon Sheehan, film collector Mickey Gold and I watched a clip of a POPULAR SCIENCE color short that appeared on the Discovery Channel (of course you’ve seen the whole short), but it was remarkable that Gordon Sheehan still remembered who the animators were who did the various scenes of ALADDIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP (1939) – and what their strengths were as artists.

I wish I knew people back then who could have talked with him and “diagramed”-out which animators did various scenes in cartoons like this. I’m glad you’ve been able to bring some of these kinds of things “to light”! Keep up the great work!

This kind of research is invaluable. There’s always something to learn. Thanks, Devon.

The story is weak but the animation still decent to good. It’s not the forties Popeye yet. Here and there, great chunks of Germanetti, who remains on his feet like the last of the romans…