This week, we present another animator/director with an extensive cartooning career, Pete Burness!

Wilson David Burness was born in Los Angeles on June 16, 1904 to his Scottish father David Burness and Nebraska-born Jennie Slatter. Soon, Burness’ parents had two daughters, Mildred and Ruth. One of his sisters began calling him “Peter,” which stuck throughout his life. He was a student of Manual Arts High School, and enrolled at the University of Southern California, in addition to artistic training at the Chouinard Art Institute. By 1930, he worked as a commercial artist and traveled to Europe to attend the World Advertising Congress in Berlin. Burness hoped to draw newspaper comic strips but entered the animation industry at the short-lived studio run by Romer Grey, which shuttered in the summer of 1931. He moved to work for Ted Esbaugh, whose outfit produced some of the earliest animated sound cartoons in color. Soon, he left Esbaugh’s studio to work for Ub Iwerks, where he animated on the Flip the Frog cartoons.

By 1933, Burness was an animator for the Van Beuren Corporation in New York, where he worked on the Little King series. Some sources believe Burness mailed his work from the West Coast to the studio, since there is no confirmed address to determine a relocation. However, Shamus Culhane and Izzy Klein, who worked at Van Beuren during that time, remember Burness’ presence; Culhane noted in Talking Animals and Other People that Burness was “the most well-dressed animator in the studio.” Burness remained at Van Beuren after Burt Gillett took over the animation department and produced the Toddle Tales and Rainbow Parades. In October 1934, Gillett was forced to make cutbacks in staff to recoup the costs of switching to color production exclusively. Burness was one of 50 artists fired from the studio.

Burness moved to Harman-Ising’s Hollywood studio. Working on the Happy Harmonies for MGM, he became one of their principal animators. After their studio went bankrupt in 1938, he joined the new MGM animation department, alternating between Rudy Ising and the new unit headed by Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera. When Ising left the studio in 1942, Burness stayed with Hanna and Barbera on their Tom and Jerry cartoons. According to an entry in Irv Spence’s diary, Burness was sent to Mexico City by MGM in January 1944. Since Burness was fluent in Spanish, he was recruited to train a crew of animators to produce cartoons at the new Caricolor Films studio headed by Manuel Moreno, a former animator for Walter Lantz.

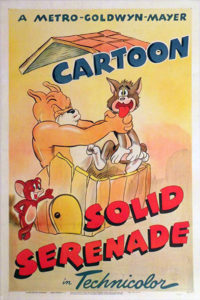

Burness returned to California by January 1945; a clipping from Daily Variety stated he was hired at Lantz’s studio. It is unclear how long he worked at Lantz, but Burness seems to have gone back to MGM. He animated on several Tom and Jerry cartoons released between 1946 and 1947, such as Trap Happy, Solid Serenade and Part Time Pal. Despite this, Burness did not receive screen credit. Sometime around early 1946, he had left MGM to work for John Sutherland’s studio, working on the stop-motion “Daffy Ditties” and The Traitor Within, a public health film for The American Cancer Society.

Burness returned to California by January 1945; a clipping from Daily Variety stated he was hired at Lantz’s studio. It is unclear how long he worked at Lantz, but Burness seems to have gone back to MGM. He animated on several Tom and Jerry cartoons released between 1946 and 1947, such as Trap Happy, Solid Serenade and Part Time Pal. Despite this, Burness did not receive screen credit. Sometime around early 1946, he had left MGM to work for John Sutherland’s studio, working on the stop-motion “Daffy Ditties” and The Traitor Within, a public health film for The American Cancer Society.

By October, Burness was hired at Warner Bros. as an animator for Chuck Jones, whom he previously worked with at Iwerks in the early 1930s. One of his earliest assignments for the studio—uncredited—was for Jones’ Haredevil Hare (released July 1948). In the cartoon, Burness animates the extended sequence where Bugs pulls a verbal switcheroo on a Martian dog to retrieve an “explosive space modulator.” Like many of his scenes in the MGM cartoons, Burness’ movement/posing on the characters had a bouncy quality that looked strikingly different than the work of the regular animators in Jones’ unit.

Burness briefly animated in Friz Freleng’s unit, credited on Wise Quackers, High Diving Hare and Curtain Razor, each released in 1949. (He animated on I Taw a Putty Tat and Kit for Cat, released a year earlier, but is not credited.) He moved to Bob McKimson’s unit and settled there until he left Warners, possibly around mid-1948; his last credit is on What’s Up Doc? (released in 1950). He went back to work for John Sutherland on industrial films distributed by MGM. Burness’ animation can be seen in Albert in Blunderland (released August 1950) and Fresh Laid Plans (released February 1951).

As evidenced from contemporary trade publications, Burness ventured into early television animation in small industrial houses. By January 1949, he and former Disney effects animator Miles Pike had worked on “Rick Rack, Special Agent”, a segment intended for NBC Comics (aka TeleComics). In one of the first animated series developed specifically for television, the TeleComics implemented comic-book style drawings filmed sequentially with vocal tracks underneath. He also worked for Animated Video Films Inc., where he supervised animation. The 1950 issue of Radio Annual and Television Yearbook lists two staffers from Warner Bros. alongside Burness; effects animator Ace Gamer acted as production manager, and Bob Gribboek was in charge of layouts and backgrounds. (On an interesting note, Dick Huemer—on staff at Disney—was in charge of story and direction.)

Burness moved to UPA as animator on at least one short (1950’s The Miner’s Daughter) but wanted to take the directorial reins. Vice president/director John Hubley offered him a chance to direct the studio’s new Mister Magoo series in the character’s third appearance Trouble Indemnity. The film was nominated for an Academy Award, but lost to another UPA cartoon, Bobe Cannon’s Gerald McBoing Boing. After Hubley directed two more Magoo cartoons, Burness became the principal director of the series. Besides theatricals, Burness also directed television commercials advertising Webster Cigars.

Burness moved to UPA as animator on at least one short (1950’s The Miner’s Daughter) but wanted to take the directorial reins. Vice president/director John Hubley offered him a chance to direct the studio’s new Mister Magoo series in the character’s third appearance Trouble Indemnity. The film was nominated for an Academy Award, but lost to another UPA cartoon, Bobe Cannon’s Gerald McBoing Boing. After Hubley directed two more Magoo cartoons, Burness became the principal director of the series. Besides theatricals, Burness also directed television commercials advertising Webster Cigars.

With the task of directing the Magoo cartoons for the studio throughout much of the 1950s, Burness was dedicated to his work, which often caused self-critical behavior. Barney Posner, an animator for Burness, recalled, “He’d break his pencils and throw them on the floor…he’d crunch up a drawing and throw it on the floor.” Magoo’s popularity with audiences earned the studio two Academy Awards for When Magoo Flew (1954) and Magoo’s Puddle Jumper (1956), both directed by Burness. Around November 1956, he was promoted to producer of the Magoo cartoons. At first a more cantankerous personality, Magoo adopted a more pleasant demeanor as the series continued. In a 1961 interview with Howard Reider, Burness felt Magoo would have been a stronger character if he maintained the personality of the earlier films.

UPA began to develop a feature-length film featuring Mr. Magoo in the mid-1950s. An adaptation of Magoo in the role of Don Quixote was planned, but ultimately scrapped. The studio chose to produce a feature based on the Arabian Nights stories, with treatments submitted all through 1957 and 1958. As production commenced around early 1958, Burness was appointed as director on the feature but he felt no connection with the material. As his son Bruce Burness wrote to historian Giannalberto Bendazzi: “My father really struggled with the idea of doing a feature-length Mr. Magoo…He became more and more distressed by what he felt was the over-commercialization of Mr. Magoo…He could not bear what he felt was the complete corruption of Mr. Magoo’s identity.” Besides his bitter feelings about the production, Burness’ health suffered; he developed ulcers. Jack Kinney, who had been fired from Disney a year earlier, recounted: “He used to quit about once a month and throw all of his furniture out in the yard there. So finally he did quit, and they asked me to take it over.”

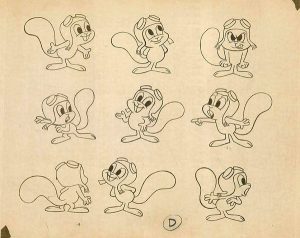

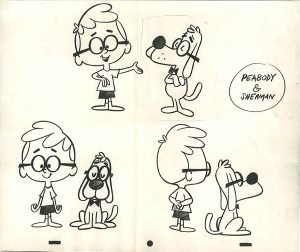

After leaving UPA, Burness rebounded to John Sutherland’s studio by April 1958 as vice-president of their animation department. A year later, he joined Jay Ward Productions on a freelance basis as they developed their new television show Rocky and His Friends. Allan Burns, one of the show’s writers, remembered Burness “always dressed in a Brooks Brothers suit and tie to draw cartoons.” Besides directing episodes, Burness also modified the model sheets for Rocky and Bullwinkle, in addition to Peabody and Sherman, previously designed by Al Shean. He also directed the pilot for Hoppity Hooper, produced in 1960, but picked up as a series three years later. In October that same year, Ward sent Burness to Mexico as a guide for Gamma Productions, the studio responsible for Rocky’s animation and photography, to oversee the visual consistency of its characters. By the end of December, he moved to Playhouse Pictures as a director of commercials.

After leaving UPA, Burness rebounded to John Sutherland’s studio by April 1958 as vice-president of their animation department. A year later, he joined Jay Ward Productions on a freelance basis as they developed their new television show Rocky and His Friends. Allan Burns, one of the show’s writers, remembered Burness “always dressed in a Brooks Brothers suit and tie to draw cartoons.” Besides directing episodes, Burness also modified the model sheets for Rocky and Bullwinkle, in addition to Peabody and Sherman, previously designed by Al Shean. He also directed the pilot for Hoppity Hooper, produced in 1960, but picked up as a series three years later. In October that same year, Ward sent Burness to Mexico as a guide for Gamma Productions, the studio responsible for Rocky’s animation and photography, to oversee the visual consistency of its characters. By the end of December, he moved to Playhouse Pictures as a director of commercials.

By July 1961, Burness returned to Jay Ward’s studio, directing the new Dudley Do-Right segments for The Bullwinkle Show. One year later, he became vice president of their commercial department, shortly after Ward’s association with Quaker Oats began. Ward also entrusted Burness to direct the animated portions of their one-hour live action variety program The Nut House, which aired once in 1963. He directed several commercials at Ward’s studio featuring Cap’n Crunch and later, Quisp and Quake. Burness continued as a director on episodes of George of the Jungle, which first aired in 1967, in addition to commercials for Quaker Oats and Aunt Jemima frozen waffle products. According to Mike Kazaleh, Burness animated on his own commercials and George episodes.

By July 1961, Burness returned to Jay Ward’s studio, directing the new Dudley Do-Right segments for The Bullwinkle Show. One year later, he became vice president of their commercial department, shortly after Ward’s association with Quaker Oats began. Ward also entrusted Burness to direct the animated portions of their one-hour live action variety program The Nut House, which aired once in 1963. He directed several commercials at Ward’s studio featuring Cap’n Crunch and later, Quisp and Quake. Burness continued as a director on episodes of George of the Jungle, which first aired in 1967, in addition to commercials for Quaker Oats and Aunt Jemima frozen waffle products. According to Mike Kazaleh, Burness animated on his own commercials and George episodes.

In 1968 as an in-betweener at Quartet Films, Mark Kausler encountered Burness, who endured further health problems: “Pete actually came in to Quartet at night to sleep on a very hard plywood bed which he had set up in the editing room.

His back was a painful mess for him, so he had to sleep on the plywood to get relief.” After facing eviction from his home, Mark returned to the studio and “Pete offered me the plywood bed for a night. I’ll never forget how stiff my back was the next morning, I could hardly move my legs at all, and my back was frozen in one painful position for a while.” Mark continued, “He seemed extremely nervous for such a seasoned professional, confiding that directing for Jay Ward was hard, for Jay scared him a little.” He soon contracted pancreatic cancer. Though he became too ill to work, Ward kept him on the company payroll—he considered Burness his favorite director at the studio. He passed away on July 21, 1969 at the age of 65.

His back was a painful mess for him, so he had to sleep on the plywood to get relief.” After facing eviction from his home, Mark returned to the studio and “Pete offered me the plywood bed for a night. I’ll never forget how stiff my back was the next morning, I could hardly move my legs at all, and my back was frozen in one painful position for a while.” Mark continued, “He seemed extremely nervous for such a seasoned professional, confiding that directing for Jay Ward was hard, for Jay scared him a little.” He soon contracted pancreatic cancer. Though he became too ill to work, Ward kept him on the company payroll—he considered Burness his favorite director at the studio. He passed away on July 21, 1969 at the age of 65.

(Thanks to Jerry Beck, Yowp, Keith Scott, Adam Abraham, Mike Kazaleh, Michael Barrier and Harvey Deneroff for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Pete Burness’s Tom always had this kind of “dopey” look to him, most often seen whenever he is hit in the face. After George Gordon and Jack Zander left, he was the only remaining animator to not draw the two bumps on the top of Tom’s chest area. Pete also animated those weird and uncanny moments like the “Don’t you believe it” in “Mouse Trouble” or the “In me power” from “The Bodyguard” (both from 1944).

He was kind of in the middle in terms of the Tom and Jerry animators; he wasn’t as crazy as Irv Spence or Jack Zander, but was also not as neat looking as Ken Muse, Ray Patterson, George Gordon, or Ed Barge.

Excellent profile. These are always a treat to read, but this one was especially well done.

I agree with Burness; Magoo was always at his best when they kept him a little cantankerous. Otherwise he came off as borderline senile.

I’m interested in hearing more about that MGM studio in Mexico. I’ve never heard of it before, so it must have not lasted long.

Great read, Devon.

Maybe not THE most compelling animator from the Golden Age, but effective enough to hang around a long time.

Burness’ theme song: I Get Around. About the only thing missing from his resume is a Heckle & Jeckle cartoon.

Great work, Devon! Nice to see more profiles of animation figures from the theatrical and early TV era!

Great piece on Burness. Irven Spence used to say “Pete Burness was his best actor”