If there’s one thing that can be said for toon justice, it’s usually swift. The animated world rarely seems to have faced the predicament presented in the famous teleplay and picture, “12 Angry Men”- where one juror is the holdout from the number necessary to reach a verdict. Nor has any cartoon jury ever announced to the judge that they’re deadlocked. In fact, nearly every verdict rendered in a cartoon appears to be unanimous – either indicating that toons are all cut of the same cloth and of like mind, or that they appoint intensely persuasive foremen of the jury. And the time it takes to reach these verdict often can’t be measured on a clock – as it is concluded before one can blink an eye. We almost never seem to have time to peek inside the jury room, and to analyze the process engaged in to reach such decisions. Is there any review of evidence? Reading back of testimony? Exchange of viewpoints between jurors? Recording of the votes? Or do toons have the innate ability to accomplish all these things through instant telepathy without a word spoken? (A great budget-saver for the animators who have to draw them, if so.) A procedural rules guide would be helpful to research this phenomenon. Perhaps a small government grant will fund the authorship of one. In the meanwhile, we are left to stare in wonderment (call it stare decisis) at the judicial process in action, including in our next series of cartoons below. One thing’s for sure – given the lack of recognizable standards for how these verdicts are reached, the ability to present a meaningful appeal from such a decision must be reduced from slim to nil.

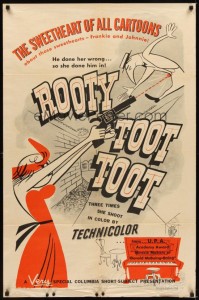

Rooty Toot Toot (UPA/Columbia, Jolly Frolics -11/15/51 – John Hubley, dir.) is both a masterpiece of modern animation and of cartoon legal tactics. The incredibly clever script, written by Bill Scott (later to achieve more widely-known fame in his partnership with Jay Ward on “Rocky and His Friends”) musically tells the story of the murder trial of “The People vs. Frankie” of the famous old song of a fatal love triangle, “Frankie and Johnny”. (Curiously, this was not the first time UPA and John Hubley had visited this song. It had appeared in previous use in the early Mr. Magoo episode, “Spellbound Hound” (1950), where Magoo mistakes an old gramophone (record player to you) for an outboard motor, and in revving up the “engine” sets off a chipmunk-speed version of the most popular version of the song by Frank Crumit (from his electrical remake in 1927 on Victor).) Graphics are exceptional, even for Hubley, with innovative minimalism of line in both character design and backgrounds, and splashes of both bright and exceptionally dark colors alternated, often deliberately failing to stay within character or object outlines or not even filling-up the areas outlined by the inkers.

Rooty Toot Toot (UPA/Columbia, Jolly Frolics -11/15/51 – John Hubley, dir.) is both a masterpiece of modern animation and of cartoon legal tactics. The incredibly clever script, written by Bill Scott (later to achieve more widely-known fame in his partnership with Jay Ward on “Rocky and His Friends”) musically tells the story of the murder trial of “The People vs. Frankie” of the famous old song of a fatal love triangle, “Frankie and Johnny”. (Curiously, this was not the first time UPA and John Hubley had visited this song. It had appeared in previous use in the early Mr. Magoo episode, “Spellbound Hound” (1950), where Magoo mistakes an old gramophone (record player to you) for an outboard motor, and in revving up the “engine” sets off a chipmunk-speed version of the most popular version of the song by Frank Crumit (from his electrical remake in 1927 on Victor).) Graphics are exceptional, even for Hubley, with innovative minimalism of line in both character design and backgrounds, and splashes of both bright and exceptionally dark colors alternated, often deliberately failing to stay within character or object outlines or not even filling-up the areas outlined by the inkers.

To set the mood, the credits of the cartoon roll in the window of a honky-tonk player piano, then the scene dissolves to the courthouse and the banging of a gavel. Frankie (that’s a girl, by the way, for those not familiar with the tune), is brought in by the jailer – but is obviously not downheartened by the forthcoming trial, as she gracefully pirouettes before the court with, as dancing partner, her defense counsel, “Honest John, the crook”. The D.A. is confident, having his evidence laid out and appropriately labeled “Exhibit “A”, “B”, etc. including a .44 revolver and a door removed from its building with three large bullet holes shot through it. Using the door to emphasize his point, the D.A. classifies it as an “open and shut case.” First witness is a bartender, whom everyone in the courtroom, including jurors and judge, seem to know by their acknowledging waves to him as he takes the stand. He testifies in flashback to Frankie having entered his establishment in what appeared to be a hostile mood, and inquiring as to the whereabouts of her sweetheart Johnny. Being an honest soul, the bartender testifies to informing her that her boyfriend was in the back room with Nelly Bly (whom we later discover is a seductive female songstress). Frankie storms down a corridor towards the back room and disappears from sight – then we hear three thunderous gunshots. Back in the present, the bartender sums up the tale – “Rooty Toot Toot – right in the snoot.” The D.A. stops to allow cross-examination, but to everyone’s surprise, Honest John declines, saying “No questions.”

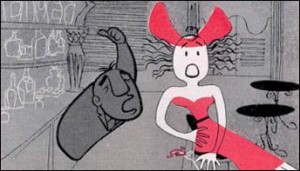

Next witness is Nelly Bly herself – so slinky, her curvaceous arms tie themselves into braids in effortless fashion. All eyes in the court are glued upon her, as she “cleans up” all inferences of anything sordid in the back-room doings, by declaring that Johnny, an adept piano player, was merely there to accompany her in a rehearsal. We now see a flashback from inside the “back room”, as Johnny, knowing of Frankie’s suspicious mind and jealous temperament, disrupts the rehearsal with nervous trembling, and creeps cautiously over to the door to check if anyone has discovered them. Before he can even open the door, he gets his answer – three bullets whiz through the door, and through him. He collapses dead on the floor, while Nelly, still completely composed and retaining her slink, opens the door. In a wonderfully posed shot of impossible perspective, the door opens to reveal Frankie, arms outstretched before her, holding the still-aimed smoking pistol. (The deliberate flatness of the perspective makes this scene incredibly fun, because if these characters were dimensional, Frankie could not possibly be in such a pose without having her arms thrust right through the wooden door!) We return back to the courtroom, where again, everyone is amazed to hear Honest John again decline cross-examination with “No questions.” By now, even Frankie is beginning to wonder what kind of an attorney she hired. Notably, as Nelly leaves the stand, everything stops for a prolonged pause, as Nelly and John exchange telling glances – almost silently conveying the famous Mae West come-on, “Come up and see me sometime”.

Next witness is Nelly Bly herself – so slinky, her curvaceous arms tie themselves into braids in effortless fashion. All eyes in the court are glued upon her, as she “cleans up” all inferences of anything sordid in the back-room doings, by declaring that Johnny, an adept piano player, was merely there to accompany her in a rehearsal. We now see a flashback from inside the “back room”, as Johnny, knowing of Frankie’s suspicious mind and jealous temperament, disrupts the rehearsal with nervous trembling, and creeps cautiously over to the door to check if anyone has discovered them. Before he can even open the door, he gets his answer – three bullets whiz through the door, and through him. He collapses dead on the floor, while Nelly, still completely composed and retaining her slink, opens the door. In a wonderfully posed shot of impossible perspective, the door opens to reveal Frankie, arms outstretched before her, holding the still-aimed smoking pistol. (The deliberate flatness of the perspective makes this scene incredibly fun, because if these characters were dimensional, Frankie could not possibly be in such a pose without having her arms thrust right through the wooden door!) We return back to the courtroom, where again, everyone is amazed to hear Honest John again decline cross-examination with “No questions.” By now, even Frankie is beginning to wonder what kind of an attorney she hired. Notably, as Nelly leaves the stand, everything stops for a prolonged pause, as Nelly and John exchange telling glances – almost silently conveying the famous Mae West come-on, “Come up and see me sometime”.

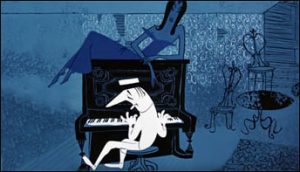

The state rests. Finally, it is John’s turn. In possibly the most incredible piece of legal wizardry in cartoon history, John neither bothers to present any new testimony or physical evidence, nor even to put Frankie on the stand. Instead, taking everything that has been submitted into evidence by the prosecution, he attempts to “sum up” for the jury the true picture they should draw from what has been presented. He asks them to picture Frankie, “pure and demure”, and in a field picking flowers, up to her locks “in flocks and flocks of hollyhocks”. We flash back to this alternate universe, Frankie’s dress transformed from its previous fiery red to pristine white with ornate patterning (an effect achieved by using a stationary pattern background underlaid behind the animation, with each cel of Frankie’s dress a transparency to let the pattern be seen within the dress outline). Enter Johnny, now weaselish in his movements and acting the cad. He offers her a randomly picked handful of posies, but, ever the spirit of purity, Frankie refuses him. Vengeful at being spurned, Johnny pulls a revolver from his pocket, and fires three shots at Frankie. Frankie holds her ground, boldly willing to take the bullets – but the shots miss, and begin following a merry zig-zag path accompanied by frenetic music, bouncing off every object in sight, in the world’s longest series of ricochets! Johnny realizes he’s in trouble, and, dropping the gun, runs wildly through the streets, with the bullets pursuing him at every turn. He ducks into the bartender’s establishment and into the back room. There, he repeats the previously seen nervous accompanyment of Nelly Bly, and the cautious creep to the door. This time, however, he gets a brief glance out the door and down the hallway. Zipping along with the speed of a comet come the three bullets! He slams the door shut, but receives the same “rooty toot toot” as in the previous flashback, falling dead again. This time, however, as Nelly opens the door, innocent Frankie childishly skips toward them down the corridor, holding loosely in one hand the dropped revolver which she intended to return to Johnny. Her reaction upon seeing Johnny on the floor is to emit a delightfully underplayed “Eek!”

The state rests. Finally, it is John’s turn. In possibly the most incredible piece of legal wizardry in cartoon history, John neither bothers to present any new testimony or physical evidence, nor even to put Frankie on the stand. Instead, taking everything that has been submitted into evidence by the prosecution, he attempts to “sum up” for the jury the true picture they should draw from what has been presented. He asks them to picture Frankie, “pure and demure”, and in a field picking flowers, up to her locks “in flocks and flocks of hollyhocks”. We flash back to this alternate universe, Frankie’s dress transformed from its previous fiery red to pristine white with ornate patterning (an effect achieved by using a stationary pattern background underlaid behind the animation, with each cel of Frankie’s dress a transparency to let the pattern be seen within the dress outline). Enter Johnny, now weaselish in his movements and acting the cad. He offers her a randomly picked handful of posies, but, ever the spirit of purity, Frankie refuses him. Vengeful at being spurned, Johnny pulls a revolver from his pocket, and fires three shots at Frankie. Frankie holds her ground, boldly willing to take the bullets – but the shots miss, and begin following a merry zig-zag path accompanied by frenetic music, bouncing off every object in sight, in the world’s longest series of ricochets! Johnny realizes he’s in trouble, and, dropping the gun, runs wildly through the streets, with the bullets pursuing him at every turn. He ducks into the bartender’s establishment and into the back room. There, he repeats the previously seen nervous accompanyment of Nelly Bly, and the cautious creep to the door. This time, however, he gets a brief glance out the door and down the hallway. Zipping along with the speed of a comet come the three bullets! He slams the door shut, but receives the same “rooty toot toot” as in the previous flashback, falling dead again. This time, however, as Nelly opens the door, innocent Frankie childishly skips toward them down the corridor, holding loosely in one hand the dropped revolver which she intended to return to Johnny. Her reaction upon seeing Johnny on the floor is to emit a delightfully underplayed “Eek!”

Honest John concludes. “You have asked for the truth, without compunction. I have performed that fiction – – – I mean, function!” He says “Bah” to the idea that his client could take a life, and announces that were she free, he’d take her for his wife! Even Frankie is now impressed, and her eyes turn to pink hearts. The jury has heard enough. With record speed, and to both the D.A.’s and judge’s dismay, they find “Not guilty!” The courtroom breaks out in a frenzy of wild and jazzy dancing celebration. It seems Frankie will have a rosy future – until the bartender beckons Frankie over and slips her a new piece of information. Honest John is exiting out the back door, accompanying Nelly Bly arm in arm! Frankie’s face first registers hopeless disappointment – then transforms into determined rage. A step away from the exit and safety, Honest John receives the retort of three more gunshots. There in the center of the courtroom stands Frankie, still holding the smoking gun in firing pose, the “Exhibit “A” tag swaying back and forth below the gun barrel. Collapsing onto the floor, Honest John declares with his last gasps, “Ipso facto. Status quo. I rest my case!”, and turns a pallid shade of blue as rigor mortis sets in. The music transforms from a dirge to decidedly uptempo, as the handcuffs go back on Frankie, and the judge, D.A. and jury now celebrate that “Frankie’s goin’ to the jailhouse, and she ain’t a-comin’ back”.

Honest John concludes. “You have asked for the truth, without compunction. I have performed that fiction – – – I mean, function!” He says “Bah” to the idea that his client could take a life, and announces that were she free, he’d take her for his wife! Even Frankie is now impressed, and her eyes turn to pink hearts. The jury has heard enough. With record speed, and to both the D.A.’s and judge’s dismay, they find “Not guilty!” The courtroom breaks out in a frenzy of wild and jazzy dancing celebration. It seems Frankie will have a rosy future – until the bartender beckons Frankie over and slips her a new piece of information. Honest John is exiting out the back door, accompanying Nelly Bly arm in arm! Frankie’s face first registers hopeless disappointment – then transforms into determined rage. A step away from the exit and safety, Honest John receives the retort of three more gunshots. There in the center of the courtroom stands Frankie, still holding the smoking gun in firing pose, the “Exhibit “A” tag swaying back and forth below the gun barrel. Collapsing onto the floor, Honest John declares with his last gasps, “Ipso facto. Status quo. I rest my case!”, and turns a pallid shade of blue as rigor mortis sets in. The music transforms from a dirge to decidedly uptempo, as the handcuffs go back on Frankie, and the judge, D.A. and jury now celebrate that “Frankie’s goin’ to the jailhouse, and she ain’t a-comin’ back”.

This was truly a milestone in “adult” animation. (Notably, it was not included in the Totally Tooned In package from Columbia, and to this day, because of its mortality rate, may not have seen a television airing.) It was justifiably nominated for an Academy Award. Unluckily, however, it was pitted against Tom and Jerry’s The Two Mouseketeers – an utterly adorable, yet plagiaristic classic (copying setup and mood heavily from the previous Oscar winner The Little Orphan (1949)). It was not yet UPA’s chance to capture the crown for innovation and ingenuity when faced with irresistible traditionalism – and thus there was no justice in the court of popular opinion.

This was another of those UPA cartoons to get caught in the “Columbia Favorite” series of reissues, with the result that its closing shot, obviously designed as a book-end match to the player piano opening, was chopped away and does not appear to exist on any known prints. I have taken great pains to recreate the lost closing on the print embedded below, using Hubley’s original drawings to continue Frankie’s walk cycle while the door of the piano window closes, and adding to the piano door the UPA logo from the previous Jolly Frolics release, The Oompahs. This is as close as you may ever get, folks, to the real thing.

Casper Takes a Bow Wow (Paramount/Famous, Casper, 12/7/51 – I. Sparber, dir.), features a brief introduction in which we visit the Spookreme Court in session. Casper is on trial for breaking ghostly laws, refusing to shriek, boo, or scare. In rhyming dialogue, the ghost jury finds Casper guilty of “friendship in the first degree”. Casper’s sentence: he is found to be “not one of us” and banished for “life with the human race”. The rest of the film is just another ho-hum effort of Casper to befriend a puppy. Surprisingly, in a bit of late inspiration for the studio, they would, possibly out of economic necessity, find something better to do with this introduction, in an episode released in the waning days of the series, discussed further below.

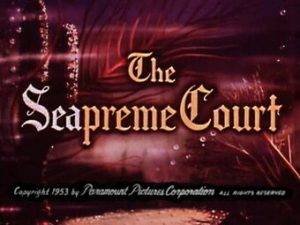

The Seapreme Court (1/29/54 – Seymour Kneitel. dir.) – As previoously mentioned, Little Audrey was a creation of the weird science of Famous Studios. She was cloned from a single cel of Little Lulu, bathed in a solution of henna rinse. Is it any wonder that Audrey would face prosecution in a dream court of similar bias to the one Lulu faced in “Musicalulu” last week? The main difference, however, is that Audrey hasn’t committed a crime that her conscience should be playing mind tricks with her about – instead, she is merely enjoying a peaceful day of fishing (and not even playing hooky, as it first appeared she was in a later episode, “Fishing Tackler”). For reasons unknown, Audrey is singled out from all the baited lines in the world to stand trial for the human world’s persecution of the underwater kingdom. In her dream, as she falls asleep beneath a tree, a fish nabs her line, pulling her into the drink instead of the other way around. Once thoroughly submerged, the fish is freed by an intervening swordfish cutting the line, while Audrey sinks to the bottom. Without even a dose of magic seaweed from the “Land of the Lost” cartoons, Audrey comes to and is able to interact with the fish without drowning. A crowd gathers around, while one fish celebrates the day’s catch: “Yay! We finally got one!” The “Carp” on the beat places Aufrey under arrest, snapping on a pair of cuffs which are really the claws of a crab. Audrey is taken before the Seapreme Court, where, as in the Musical Court of Justice, all proceedings take place in rhyme. An octopus acts as a holding cell for Audrey, surrounding her with its tentacles as bars.

The Seapreme Court (1/29/54 – Seymour Kneitel. dir.) – As previoously mentioned, Little Audrey was a creation of the weird science of Famous Studios. She was cloned from a single cel of Little Lulu, bathed in a solution of henna rinse. Is it any wonder that Audrey would face prosecution in a dream court of similar bias to the one Lulu faced in “Musicalulu” last week? The main difference, however, is that Audrey hasn’t committed a crime that her conscience should be playing mind tricks with her about – instead, she is merely enjoying a peaceful day of fishing (and not even playing hooky, as it first appeared she was in a later episode, “Fishing Tackler”). For reasons unknown, Audrey is singled out from all the baited lines in the world to stand trial for the human world’s persecution of the underwater kingdom. In her dream, as she falls asleep beneath a tree, a fish nabs her line, pulling her into the drink instead of the other way around. Once thoroughly submerged, the fish is freed by an intervening swordfish cutting the line, while Audrey sinks to the bottom. Without even a dose of magic seaweed from the “Land of the Lost” cartoons, Audrey comes to and is able to interact with the fish without drowning. A crowd gathers around, while one fish celebrates the day’s catch: “Yay! We finally got one!” The “Carp” on the beat places Aufrey under arrest, snapping on a pair of cuffs which are really the claws of a crab. Audrey is taken before the Seapreme Court, where, as in the Musical Court of Justice, all proceedings take place in rhyme. An octopus acts as a holding cell for Audrey, surrounding her with its tentacles as bars.

A 12 member jury is empaneled by unrolling with a key the metal lid of a sardine can. The sardines promise an “oily” verdict. No attorneys participate, the judge instead taking direct testimony from witnesses (another cartoon case of cutting out the middlemen). First witness sworn is Willie Weakfish, a junior member of the community of “school” age. He presents an item of physical evidence – a hook, with most of its curved shaft disguised to look like a peppermint candy cane, upon which Willie almost bit. Next witness: a sailfish, who himself serves as an exhibit – as he speaks from his present position after the humans got through with him – mounted on a plaque. A whale next testifies to being “drained of my winter oil”, displaying an automotive dip stick in his blow hole, with a reading of empty. Final testimony is provided by the widow Salmon, who is left with a goldfish bowl of children to attend to, while holding up to the court’s view her husband – in a can. Of course, verdict is unanimous and swift – guilty. Audrey’s sentence – a seat in the Eel-lectric Chair. Audrey, as resourceful as Lulu, of course attempts an escape, tying the octopus’s tentacles into knots. She encounters various resistance, including a squad of Carps mounted on sea horses, a dueling swordfish, and finally an encirclement of swordfish which plant their noses in the bottom sand, again serving as an imprisonment for Audrey. As she is placed upon the eel-lectric chair and the current begins to surge, Aufrey awakens to find a real bite upon her line. She releses the “poor fishie”, them pours all her worms into the sea unhooked to give the fish a tasty treat. The fish submerges, then returns, leaping onto Audrey’s chest and pinning upon her a badge, reading “Of-fish-ial Pardon”.

A 12 member jury is empaneled by unrolling with a key the metal lid of a sardine can. The sardines promise an “oily” verdict. No attorneys participate, the judge instead taking direct testimony from witnesses (another cartoon case of cutting out the middlemen). First witness sworn is Willie Weakfish, a junior member of the community of “school” age. He presents an item of physical evidence – a hook, with most of its curved shaft disguised to look like a peppermint candy cane, upon which Willie almost bit. Next witness: a sailfish, who himself serves as an exhibit – as he speaks from his present position after the humans got through with him – mounted on a plaque. A whale next testifies to being “drained of my winter oil”, displaying an automotive dip stick in his blow hole, with a reading of empty. Final testimony is provided by the widow Salmon, who is left with a goldfish bowl of children to attend to, while holding up to the court’s view her husband – in a can. Of course, verdict is unanimous and swift – guilty. Audrey’s sentence – a seat in the Eel-lectric Chair. Audrey, as resourceful as Lulu, of course attempts an escape, tying the octopus’s tentacles into knots. She encounters various resistance, including a squad of Carps mounted on sea horses, a dueling swordfish, and finally an encirclement of swordfish which plant their noses in the bottom sand, again serving as an imprisonment for Audrey. As she is placed upon the eel-lectric chair and the current begins to surge, Aufrey awakens to find a real bite upon her line. She releses the “poor fishie”, them pours all her worms into the sea unhooked to give the fish a tasty treat. The fish submerges, then returns, leaping onto Audrey’s chest and pinning upon her a badge, reading “Of-fish-ial Pardon”.

Bugs Bonnets (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 1/14/56 – Chuck Jones, dir.) We’ve once previously had occasion to visit this title on a prior trail – a curious and novel experiment with the concept, “clothes make the man” by setting up a visual experiment in Bugs’ Bunny’s forest of having a van full of various hats spill its entire inventory willy-nilly on a windy day throughout the countryside. With every change of wind direction, a new hat is blown upon the brows of Bugs and Elmer – causing radical changes in their personas and demeanors to match the type of chapeau acquired. Bugs acquires a gangster’s hat resembling the kind of thing Humphrey Bogart would feel comfortable in, amd emerges from behind a rock smoking a cigar and flipping a coin in the manner of George Raft. “I told ya, Mulrooney, that dis’ was my territory”, begins Bugs to Elmer. “I’m gonna rub ya’ out, see?”, he continues, blowing smoke into Elmer’s face from the cigar. Down from the sky floats a policeman’s hat onto Elmer. “Alwight, Wocky! You’re coming with me, you malefactor”, says Elmer, seizing Bugs by the neck fur. “Hey, look, copper, we can settle this out of court”, whispers Bugs conspiratorially into Elmer’s ear, handing him a stack of greenbacks. “Moola, yeah. Ten G’s.” Elmer, outraged at the money thrust into his hand, states, “How dare you try to bwibe me, you miscweant.” But before he can say another word to the wabbit, a judge’s powdered wig lands on Bugs to replace the gangster’s hat. Bugs immediately assumes the stern, unyielding stare of a judicial officer, as hapless Elmer finds himself before the eyes of authority, with the incriminating money still held in his red-handed palm. Elmer nervously mops his brow with the stack of bills, while Bugs asks in intimidating tone, “Well?” As Elmer stammers with nothing to say in his defense, Bugs delivers verdict: “You’re a family man. Monahan, so I’m only going to sentence you to 45 years – at hard labor.” Bugs walks away, muttering “One thing I cannot abide is a dishonest police officer.” Wonder if this example of Bugs’ unswaying judicial form will win him a real-life judicial appointment, as with Betty Boop?

Bugs Bonnets (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 1/14/56 – Chuck Jones, dir.) We’ve once previously had occasion to visit this title on a prior trail – a curious and novel experiment with the concept, “clothes make the man” by setting up a visual experiment in Bugs’ Bunny’s forest of having a van full of various hats spill its entire inventory willy-nilly on a windy day throughout the countryside. With every change of wind direction, a new hat is blown upon the brows of Bugs and Elmer – causing radical changes in their personas and demeanors to match the type of chapeau acquired. Bugs acquires a gangster’s hat resembling the kind of thing Humphrey Bogart would feel comfortable in, amd emerges from behind a rock smoking a cigar and flipping a coin in the manner of George Raft. “I told ya, Mulrooney, that dis’ was my territory”, begins Bugs to Elmer. “I’m gonna rub ya’ out, see?”, he continues, blowing smoke into Elmer’s face from the cigar. Down from the sky floats a policeman’s hat onto Elmer. “Alwight, Wocky! You’re coming with me, you malefactor”, says Elmer, seizing Bugs by the neck fur. “Hey, look, copper, we can settle this out of court”, whispers Bugs conspiratorially into Elmer’s ear, handing him a stack of greenbacks. “Moola, yeah. Ten G’s.” Elmer, outraged at the money thrust into his hand, states, “How dare you try to bwibe me, you miscweant.” But before he can say another word to the wabbit, a judge’s powdered wig lands on Bugs to replace the gangster’s hat. Bugs immediately assumes the stern, unyielding stare of a judicial officer, as hapless Elmer finds himself before the eyes of authority, with the incriminating money still held in his red-handed palm. Elmer nervously mops his brow with the stack of bills, while Bugs asks in intimidating tone, “Well?” As Elmer stammers with nothing to say in his defense, Bugs delivers verdict: “You’re a family man. Monahan, so I’m only going to sentence you to 45 years – at hard labor.” Bugs walks away, muttering “One thing I cannot abide is a dishonest police officer.” Wonder if this example of Bugs’ unswaying judicial form will win him a real-life judicial appointment, as with Betty Boop?

Rocket Squad (Warner, Porky and Daffy, 3/10/56, Chuck Jones, dir.) is, I believe, anumation’s second major “Dragnet” parody (following Woody Woodpecker’s “Under the Counter Spy; it itself would be followed a few short months later by Terrytoons’ “Police Dogged”). The episode title lampoons another cops and robbers drama of the day, “Racket Squad”, which had already ended its first-run life and no doubt was in re-syndication. “The story you are about to see is true. The drawings have been changed to protect the innocent.” Jones and writer Tedd Pierce retain most of the foibles, bells and whistles of Jack Webb’s counterpart, but move the setting to the space-age world of the future – a cross between “Duck Dodgers” (actually reusing some animation from said previous short) and the world that would in a few years be populated by the Jetsons. This allows officers Daffy and Porky (aka Monday and Tuesday (he always follows me)) the chance to patrol in saucer cars (while Porky corrects each date and time Daffy narrates in the chain of events during the investigation), and utilize the computerized high-tech of a modern space crime lab (modern, but with an antique touch, as, in its search for suspects, the machinery selects an IBM punch card which is played through a player piano, and identifies musically the suspect, “Mother” Machree). The Machree file (a long one, extending out of the file cabinet the width of the room) reveals other aliases: “Danny Boy”. “Wild Irisn Mose”, and “Eddie the Fagan” (someone explain to me the last one). “This criminal was so clever he’d never been suspected of anything”, narrates Daffy. A television screen on a “suspect locator” is employed by pressing a labeled typewriter key button bearing the suspect’s name (and we think we’ve got no privacy with global positioning on cell phones!). Other keys are pre-labeled with a who’s who of persons under Warner employ, including Mel Blanc, Norman Moray, Eddie Seltzer, John Burton, Tedd Pierce, and C.M. Jones. An aerial pursuit ensues at a drive in built for space saucers, and through a smogbank over Los Angeles. Trial is held in Ultra-Superior Court 13527B, Department of Astral Justice. As a result, the two arresting officers are sentenced to 20 years for false arrest. Porky corrects Mel as narrator, indicating that sentence was really “30 years”.

Rocket Squad (Warner, Porky and Daffy, 3/10/56, Chuck Jones, dir.) is, I believe, anumation’s second major “Dragnet” parody (following Woody Woodpecker’s “Under the Counter Spy; it itself would be followed a few short months later by Terrytoons’ “Police Dogged”). The episode title lampoons another cops and robbers drama of the day, “Racket Squad”, which had already ended its first-run life and no doubt was in re-syndication. “The story you are about to see is true. The drawings have been changed to protect the innocent.” Jones and writer Tedd Pierce retain most of the foibles, bells and whistles of Jack Webb’s counterpart, but move the setting to the space-age world of the future – a cross between “Duck Dodgers” (actually reusing some animation from said previous short) and the world that would in a few years be populated by the Jetsons. This allows officers Daffy and Porky (aka Monday and Tuesday (he always follows me)) the chance to patrol in saucer cars (while Porky corrects each date and time Daffy narrates in the chain of events during the investigation), and utilize the computerized high-tech of a modern space crime lab (modern, but with an antique touch, as, in its search for suspects, the machinery selects an IBM punch card which is played through a player piano, and identifies musically the suspect, “Mother” Machree). The Machree file (a long one, extending out of the file cabinet the width of the room) reveals other aliases: “Danny Boy”. “Wild Irisn Mose”, and “Eddie the Fagan” (someone explain to me the last one). “This criminal was so clever he’d never been suspected of anything”, narrates Daffy. A television screen on a “suspect locator” is employed by pressing a labeled typewriter key button bearing the suspect’s name (and we think we’ve got no privacy with global positioning on cell phones!). Other keys are pre-labeled with a who’s who of persons under Warner employ, including Mel Blanc, Norman Moray, Eddie Seltzer, John Burton, Tedd Pierce, and C.M. Jones. An aerial pursuit ensues at a drive in built for space saucers, and through a smogbank over Los Angeles. Trial is held in Ultra-Superior Court 13527B, Department of Astral Justice. As a result, the two arresting officers are sentenced to 20 years for false arrest. Porky corrects Mel as narrator, indicating that sentence was really “30 years”.

Assault and Flattery (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 7/6/56 – I. Sparber, dir.) – Finally realizing mere fisticuffs never seems to prevail against Popeye’s strength, Bluto employs the wheels of the justice system as a weapon againt the sailor – taking him to court on charges of assault and battery. An assault is defined as demonstration of an unlawful intent to inflict immediate injury upon another. A battery is defined as an intentional, unlawful and harmful contact with another person. Each of these torts requires an intent to harm or willful disregard for the other’s rights. Defense of one’s person or property, or defense of another, may provide a legal defense sufficient to defeat a finding of intent to harm. It is here that Bluto’s case goes wrong, as, while he can describe the blows to Judge Wimpy (who listens to testimony between taking time out to swallow hamburgers whole, or sympathetically weeps, even though the tears are brought on by slicing onions for his burgers), Bluto presents no specific evidence of the events preceding the blows, laying no foundation for the requisite intent to make the beatings a basis for conviction. In an extended series of “cheater” clips (taking up easily two-thirds of the cartoon’s footage), Popeye presents events leading up to the beatings, properly displaying his reasons for laying blows on Bluto, and a solid case for self-defense of himself and of Olive. Bluto’s evidence is deemed insufficient, and a verdict is entered in favor of Popeye. Bluto (who has appeared throughout the trial in leg and arm casts and in a wheelchair, casts off the chair and bindings, demonstrating that he’s been faking all along, complaining “That ain’t justice!” The usual brawl ensues, in the presence of the court. Popeye downs his spinach, socking Bluto across the courtroom. Acquiring a can of black paint, Popeye speeds to outrace Bluto to the opposite wall, where he spreads black paint across a set of window blinds. Bluto slams into the window, acquiding a set of black stripes across his sailor suit – an indicia of where he’s going when Popeye presses criminal charges.

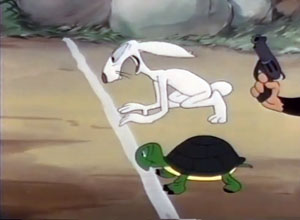

A Hare-Breadth Finish (Terrytoons/Fox, 2/1/57 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – This isn’t really a courtroom cartoon, but a run-in with the law at the police station during booking. Nevertheless, it has such a feel of films such as The Trial of Mr. Wolf, and is such a tribute to the tradition of Warner Bros, that I am inclined to cheat to permit its inclusion here, as one of my favorite late items from the original Terrytoons units.

After a successful trilogy of “tortoise and hare” spoofs for Bugs Bunny at Warner Brothers, showcasing the approaches of three different directors (Tex Avery, Bob Clampett, and Friz Freleng), the Warner boys ran out of inspiration, and let their new character of Cecil Turtle lapse into the temporarily forgotten, making no new appearances after about a decade. Memories were often long at Terrytoons, however, and someone in their story department appears to have decided the time was ripe for someone else to carry the torch for the further lampooning of this traditional storybook classic. Picking up immediately where Warner left off, the story opens with the hare being dragged to the station in handcuffs, struggling every step of the way and demanding to be let go. He is brought up for booking on charges of resisting an officer, and exceeding the speed limit. Dropping his fierce resistance, the hare pleads for understanding, and identifies himself as the hare that lost the legendary race to the tortoise. He complains that the officer spoiled the only chance the hare had to redeem himself, and tells his tale of woe.

The hare recounts how, after the first race, he couldn’t live down the disgrace of his loss. He faced jeering and ridicule by the forest animals wherever he went, and was “a marked hare” (illustrated by a visible “X” appearing on his back). He got to even hate himself, making faces at his reflection in the mirror, and smashing himself on the head with a mallet. He finally resolved that he had to race the tortoise again, and beat him.

The hare recounts how, after the first race, he couldn’t live down the disgrace of his loss. He faced jeering and ridicule by the forest animals wherever he went, and was “a marked hare” (illustrated by a visible “X” appearing on his back). He got to even hate himself, making faces at his reflection in the mirror, and smashing himself on the head with a mallet. He finally resolved that he had to race the tortoise again, and beat him.

He spends the winter at the dog track in Florida, training himself by serving as a live version of the electric rabbit the dogs chase during the races. He got to be so fast, he could take off and meet himself coming back – visually illustrated by a double exposure demonstration. Now ready, the rematch was scheduled. The hare vowed this time to take no chances – but immediately reduces his chances by looking back over his shoulder for the tortoise – and running straight into a tree trunk, knocking himself cold. The creeping tortoise (whom Philip Scheib devises a clever musical motif for in low-register saxophone) walks right over the prone hare, stepping on his face as he goes. As the hare comes to, the tortiose is a half-mile ahead. The hare quickly catches up, passing the tortiose, and digging a pit in the tortoise’s path, covered over with a coating of straw. The tortoise falls in, and is promptly buried deep by the hare, packing down the dirt with his shovel. Despite these efforts, the tortoise seems to have natural tunneling ability, and emerges effortlessly from the dirt, carrying the hare with ease atop his shell. (An interesting animation note: several action scenes are contributed by Jim Tyer. Tyer’s shots noticeably differ in detail on the tortoise from those of other animators, as Tyer’s tortoise has completely green feet, while other shots all depict the tortoise with black toenails.) The hare takes off in the lead again, crossing a rope bridge over a crevasse, and running so fast, his shadow trails behind, perspiring, and finally collapses to seat itself on a rock while the hare impatiently waits for the shadow to catch its second wind. Meanwhile, the tortoise has reached the rope bridge. The hare’s shadow signals the hare of the tortoise’s approach, and the two of them rejoin as one and return to the rope bridge, the hare cutting the ropes. The bridge falls out from under the tortoise, and he plunges into the canyon. A shot tracking his fall has very neat animation, which comes as close to depicting the tortoise as an identical twin to Cecil Turtle as could possibly be imagined. The tortoise slowly thinks out his predicament, then opens his shell to step out of it in underwear, carrying a small satchel – precisely timing his step so that he places his foot firmly on the approaching ground, while the shell cracks into a million fragments. (A gag quite similar to the telephone booth plummet in MGM’s “Barney’s Hungry Cousin”).

Out of his satchel, the tortoise produces a spare shell, far too large to have fit in the bag in the first place, and is restored to normal to resume the race. As he passes a tree ahead, the hare leaps out, and captures the tortoise in a box, which he quickly ties in wrapping paper. Applying stamps, the hare addresses the parcel to Hawaii, and with a rubber stamp adds additional inked instructions – “Handle without care”. Dropping the package in a mailbox, the hare races ahead, presuming himself now alone in the competition. But a mail plane swoops over him, dropping a package onto the track. The writers obviously remember Chuck Jones’s recurring travel gag of shipping Charlie Dog off to remote locales, always to return in traditional costume of the destination – as out of the box emerges the tortoise, in a hilarious piece of Jim Tyer animation, dressed in a grass skirt and flower lei, and playing a ukelele – with the goofiest smile on his face, his only piece of personality animation in the whole picture. Extreme measures are in order, and the hare runs ahead to an explosives shack, obraining a black bomb and a dynamite plunger. As the tortoise passes another tree, the hare creeps behind him, slipping the wired bomb under the tortoise’s shell, then running back to the plunger. Regrettably, the hare seems to have his wires crossed, and the explosion emits from the plunger instead of the bomb. The hare is blasted miles backwards, coming to rest atop a hill. As he shakes himself to regain his bearings, he has to pull out a telescope to determine the tortoise’s position – mere feet away from the finish line. In another expressive piece of Tyer animation, the hare pours on whirlwind speed to descend the hill, catching up to and passing the tortoise. As the hare is about to claim victory, his path is blocked by the arresting officer, who announces that the hare was clocked by radar exceeding the speed limit. The wide-bodied cop begins writing a ticket, as the hare begs insistently that he’s got to get by, extending his toes between the cop’s legs as far as he can in a futile effort to cross the finish line. The tortoise saunters by at his own creeping pace, winning the race unopposed, as the hare shrinks into a small, withering mess from the agony of defeat. The scene returns to the police station. As a tinkling piano plays a sort of gay-90’s “hearts and flowers” riff of sentimentality, the hare concludes, “And that’s what happened. I woulda won. I coulda redeemed myself and this palooka spoiled it all. He ruined me.” Breaking down and sobbing on the floor, the hare cries, “I can’t win. I just can’t win!” The chief and the arresting officer suddenly open their uniforms and remove a pair of masks , revealing three other tortoises (as in Avery’s “Tortoise Beats Hare”), who state with a wink to the audience, “He’s so right!”

Out of his satchel, the tortoise produces a spare shell, far too large to have fit in the bag in the first place, and is restored to normal to resume the race. As he passes a tree ahead, the hare leaps out, and captures the tortoise in a box, which he quickly ties in wrapping paper. Applying stamps, the hare addresses the parcel to Hawaii, and with a rubber stamp adds additional inked instructions – “Handle without care”. Dropping the package in a mailbox, the hare races ahead, presuming himself now alone in the competition. But a mail plane swoops over him, dropping a package onto the track. The writers obviously remember Chuck Jones’s recurring travel gag of shipping Charlie Dog off to remote locales, always to return in traditional costume of the destination – as out of the box emerges the tortoise, in a hilarious piece of Jim Tyer animation, dressed in a grass skirt and flower lei, and playing a ukelele – with the goofiest smile on his face, his only piece of personality animation in the whole picture. Extreme measures are in order, and the hare runs ahead to an explosives shack, obraining a black bomb and a dynamite plunger. As the tortoise passes another tree, the hare creeps behind him, slipping the wired bomb under the tortoise’s shell, then running back to the plunger. Regrettably, the hare seems to have his wires crossed, and the explosion emits from the plunger instead of the bomb. The hare is blasted miles backwards, coming to rest atop a hill. As he shakes himself to regain his bearings, he has to pull out a telescope to determine the tortoise’s position – mere feet away from the finish line. In another expressive piece of Tyer animation, the hare pours on whirlwind speed to descend the hill, catching up to and passing the tortoise. As the hare is about to claim victory, his path is blocked by the arresting officer, who announces that the hare was clocked by radar exceeding the speed limit. The wide-bodied cop begins writing a ticket, as the hare begs insistently that he’s got to get by, extending his toes between the cop’s legs as far as he can in a futile effort to cross the finish line. The tortoise saunters by at his own creeping pace, winning the race unopposed, as the hare shrinks into a small, withering mess from the agony of defeat. The scene returns to the police station. As a tinkling piano plays a sort of gay-90’s “hearts and flowers” riff of sentimentality, the hare concludes, “And that’s what happened. I woulda won. I coulda redeemed myself and this palooka spoiled it all. He ruined me.” Breaking down and sobbing on the floor, the hare cries, “I can’t win. I just can’t win!” The chief and the arresting officer suddenly open their uniforms and remove a pair of masks , revealing three other tortoises (as in Avery’s “Tortoise Beats Hare”), who state with a wink to the audience, “He’s so right!”

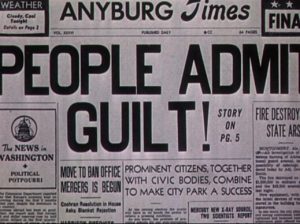

The Story of Anyburg, U.S.A. (Disney, 6/19/57 – Clyde Geronimi, dir.), must rank as among the most obscure theatrical works of the studio in the 1950’s, possibly only exceeded in such category by Jack and Old Mac. I believe it had one run on the Disney Channel decades ago, and since then seems to have been relegated to the “Disney Rarities” DVD tin. It’s actually an interesting – if a little extreme – semi-educational film, in similar vein to “How To Have an Accident In the Home” or the later “Freewayphobia” episodes of the 1960’s. The setting is almost entirely within the courtroom, with most dialogue again in rhyme. (Did this become a local court rule in Toontown, that testimony and cross-examination must be delivered in couplets?) Anyway, the citizens have taken a stand against the chaos and confusion that has arisen from the invasion of mass numbers of automobiles and the super-highway system – and have placed the automobile world on trial for its life, with objective to ban them from human society. Testifying members of the auto universe resemble cast members of “Susie, the Little Blue Coupe”, or their successors-to-be from the “Cars” franchise. A sterling voice cast includes Hans Conreid as the almost diabolical prosecuting attorney (this may have been his last voice work behind the camera for Disney, excepting his on-screen appearance as the live-action “Magic Mirror” in “Disney’s Greatest Villains” for the Wonderful World.), Bill Thompson as defense counsel, and Thurl Ravenscroft as a highway designer and other incidental voices. With every bit of oily slipperiness he can verbally muster, the prosecutor dramatically confronts each witness, and thrusts his opinions upon a seemingly favorable jury eager to find a basis for conviction. The judge is a stern curmudgeon, most interested in moving the case along at a brisk pace, as his golf clubs are stashed behind the podium and he declares he must be soon “toddling”. The defense attorney is a little man with big ideas – which he largely keeps to himself until it is time to present his defense, sharing in tactics with Honest John from “Rooty Toot Toot” and preferring to ask “No questions” from potentially negative witnesses. The prosecutor calls to the stand a small coupe names “Lizzie”, very similar in style to Susie, accusing her of making a mockery of speed limits, crashing into a restaurant window, then stealing away to leave the demiltion and numerous cases of indigestion behind her.

The Story of Anyburg, U.S.A. (Disney, 6/19/57 – Clyde Geronimi, dir.), must rank as among the most obscure theatrical works of the studio in the 1950’s, possibly only exceeded in such category by Jack and Old Mac. I believe it had one run on the Disney Channel decades ago, and since then seems to have been relegated to the “Disney Rarities” DVD tin. It’s actually an interesting – if a little extreme – semi-educational film, in similar vein to “How To Have an Accident In the Home” or the later “Freewayphobia” episodes of the 1960’s. The setting is almost entirely within the courtroom, with most dialogue again in rhyme. (Did this become a local court rule in Toontown, that testimony and cross-examination must be delivered in couplets?) Anyway, the citizens have taken a stand against the chaos and confusion that has arisen from the invasion of mass numbers of automobiles and the super-highway system – and have placed the automobile world on trial for its life, with objective to ban them from human society. Testifying members of the auto universe resemble cast members of “Susie, the Little Blue Coupe”, or their successors-to-be from the “Cars” franchise. A sterling voice cast includes Hans Conreid as the almost diabolical prosecuting attorney (this may have been his last voice work behind the camera for Disney, excepting his on-screen appearance as the live-action “Magic Mirror” in “Disney’s Greatest Villains” for the Wonderful World.), Bill Thompson as defense counsel, and Thurl Ravenscroft as a highway designer and other incidental voices. With every bit of oily slipperiness he can verbally muster, the prosecutor dramatically confronts each witness, and thrusts his opinions upon a seemingly favorable jury eager to find a basis for conviction. The judge is a stern curmudgeon, most interested in moving the case along at a brisk pace, as his golf clubs are stashed behind the podium and he declares he must be soon “toddling”. The defense attorney is a little man with big ideas – which he largely keeps to himself until it is time to present his defense, sharing in tactics with Honest John from “Rooty Toot Toot” and preferring to ask “No questions” from potentially negative witnesses. The prosecutor calls to the stand a small coupe names “Lizzie”, very similar in style to Susie, accusing her of making a mockery of speed limits, crashing into a restaurant window, then stealing away to leave the demiltion and numerous cases of indigestion behind her.

Trembling, the rattling vehicle stammers an admission of the charges. Next, the prosecutor calls a sports car, who is accused of guzzling alcohol, spitting flames, and burning rubber. The show-off car receives the charges with a satisfied pride and self-satisfaction, and responds, “Hey, you ought to know”. “A hopeless case”, the prosecutor classifies him. Next, a quite battered old heap with only half a windshield (amounting to just one eye), no brakes, and shot tires – “The type every safety test shuns!”, shouts the prosecutor. Then, the prosecutor calls on testimony of safety engineers, who have designed bodies of steel, safety glass, puncture-proof tires, etc., but all concede that despite their efforts, accident numbers continue to grow. “And so you see, the automobile must GO!”, summarizes the prosecutor. Finally, the prosecutor puts on the stand the designer of the superhighways – who bursts into tears that his highways were equipped with every sign, signal, and marking to make them safe – but were ruined by those infernal automobiles. The prosecution rests, with the stated assurance that the jury will bring in a verdict of “GUILTY!” (as the prosecutor sprouts a devil’s horns and tail). The defense now faces the jury, presenting graphics from a sort of projectorless screen, predicting Phineas J. Whoopee’s 3D blackboard from the later “Tennessee Tuxedo”. (It always helps a jury presentation to add audio-visual.) He illustrates various types of driving menaces, but by means of a fade away, reveals that behind every menacing auto, there is actually in control a menacing human driver. In perhaps the most extreme shot, he illustrates a police line-up of average citizens guilty of traffic crimes – who transform before our eyes into deranged lunatics wielding pistols, Tommy-guns, and black bombs, to depict how dangerous they are. The courtroom lights are brought up, and the defense counsel finds himself in an empty courtroom save for the autos, with notes on the jury box, prosecutor’s desk, and judge’s bench, reading, respectively, “Not guilty”, “You win”, and “Case adjourned.” The humans concede their guilt and have crept off in shame, while the autos and defense counsel celebrtate a victory. A narrator states that a new era of courteous driving swept the nation, and sanity returned to the roadways – but not for long – and before you know it, the roads are looking as erratically-driven and snarled as they did at the beginning of the picture. The narrator concludes, “Well, it was a nice try, and where there’s life, there’s hope – Let’s hope!”

Trembling, the rattling vehicle stammers an admission of the charges. Next, the prosecutor calls a sports car, who is accused of guzzling alcohol, spitting flames, and burning rubber. The show-off car receives the charges with a satisfied pride and self-satisfaction, and responds, “Hey, you ought to know”. “A hopeless case”, the prosecutor classifies him. Next, a quite battered old heap with only half a windshield (amounting to just one eye), no brakes, and shot tires – “The type every safety test shuns!”, shouts the prosecutor. Then, the prosecutor calls on testimony of safety engineers, who have designed bodies of steel, safety glass, puncture-proof tires, etc., but all concede that despite their efforts, accident numbers continue to grow. “And so you see, the automobile must GO!”, summarizes the prosecutor. Finally, the prosecutor puts on the stand the designer of the superhighways – who bursts into tears that his highways were equipped with every sign, signal, and marking to make them safe – but were ruined by those infernal automobiles. The prosecution rests, with the stated assurance that the jury will bring in a verdict of “GUILTY!” (as the prosecutor sprouts a devil’s horns and tail). The defense now faces the jury, presenting graphics from a sort of projectorless screen, predicting Phineas J. Whoopee’s 3D blackboard from the later “Tennessee Tuxedo”. (It always helps a jury presentation to add audio-visual.) He illustrates various types of driving menaces, but by means of a fade away, reveals that behind every menacing auto, there is actually in control a menacing human driver. In perhaps the most extreme shot, he illustrates a police line-up of average citizens guilty of traffic crimes – who transform before our eyes into deranged lunatics wielding pistols, Tommy-guns, and black bombs, to depict how dangerous they are. The courtroom lights are brought up, and the defense counsel finds himself in an empty courtroom save for the autos, with notes on the jury box, prosecutor’s desk, and judge’s bench, reading, respectively, “Not guilty”, “You win”, and “Case adjourned.” The humans concede their guilt and have crept off in shame, while the autos and defense counsel celebrtate a victory. A narrator states that a new era of courteous driving swept the nation, and sanity returned to the roadways – but not for long – and before you know it, the roads are looking as erratically-driven and snarled as they did at the beginning of the picture. The narrator concludes, “Well, it was a nice try, and where there’s life, there’s hope – Let’s hope!”

Not Ghoulty (Paramount/Famous, Casper, 6/5/59 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) was released during a time when the studio was attempting to survive under severe budgetary cuts, necessitating major streamlining and shortcuts to the animation process, and/or the use of substantial “cheater” footage to keep production costs down. This episode uses both methods of price reduction – yet manages to come up with something creatively different and off the beaten path for the series. The film opens with the identical court trial previously seen in Casper Takes a Bow Wow, discussed above. It changes direction by adding a new shot or two, and intercutting previous clips from Ghost of the Town, another out-of-the-ordinary installment of the series, in which Casper saves a child from a burning building, and becomes recognized by the humans as a public hero – indicating that this time, Casper has really violated ghostly laws by actually succeeding in making friends. For this even more extreme violation of whatever penal code ghosts abide by, the judge issues a verdict more severe than mere banishment to live among the humans – a loss of ghostly powers, until Casper can demonstrate that he’s scared someone. Under usual circumstances in the series, this would seem a snap, as Casper’s always scaring people accidentally. But the proviso seems to be that the scare must be intentional – coupled with the difficulty that now, with his public notoriety, no one is accidentally afraid of him anymore. A tricky situation indeed. Casper solemnly leaves the courtroom – for the first time having to pause to open the door instead of merely walking through it.

Not Ghoulty (Paramount/Famous, Casper, 6/5/59 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) was released during a time when the studio was attempting to survive under severe budgetary cuts, necessitating major streamlining and shortcuts to the animation process, and/or the use of substantial “cheater” footage to keep production costs down. This episode uses both methods of price reduction – yet manages to come up with something creatively different and off the beaten path for the series. The film opens with the identical court trial previously seen in Casper Takes a Bow Wow, discussed above. It changes direction by adding a new shot or two, and intercutting previous clips from Ghost of the Town, another out-of-the-ordinary installment of the series, in which Casper saves a child from a burning building, and becomes recognized by the humans as a public hero – indicating that this time, Casper has really violated ghostly laws by actually succeeding in making friends. For this even more extreme violation of whatever penal code ghosts abide by, the judge issues a verdict more severe than mere banishment to live among the humans – a loss of ghostly powers, until Casper can demonstrate that he’s scared someone. Under usual circumstances in the series, this would seem a snap, as Casper’s always scaring people accidentally. But the proviso seems to be that the scare must be intentional – coupled with the difficulty that now, with his public notoriety, no one is accidentally afraid of him anymore. A tricky situation indeed. Casper solemnly leaves the courtroom – for the first time having to pause to open the door instead of merely walking through it.

Casper tries to bluff his way through an average day about town, thinking, how bad can it be? But being a mere average Joe – er, sheet – is not easy when all your human friends know you for lending a helping hand with your usual special brand of ectoplasmic magic. Casper passes a construction worker on a high girder above and exchanges greetings, then hears another shout from above, as the worker loses his footing and dangles from the girder, claiming he can’t hold on much longer. A cop on the beat says, “Quick, Casper. Fly up there and help him.” Forgetting the court sentence, Casper runs to gain flying speed, leaps into the air, and falls flat on his belly, landing on the business end of a shovel. Like a flipped tablespoon, the shovel flies into the air, hitting a board in a floor above, on top of which is a pail of hot rivets. One rivet flies out of the pail, and lands on the worker’s hands. He shouts in pain and loses his grip on the girder, falling down below, where his life is only saved by landing in a mixing vat of wet cement. As Casper asks if he’s all right, the worker replies, “A fine friend you are. Beat it!” Down the street, a shopkeeper is having trouble with his door key, and asks Casper to go through the window and open the door from the inside. Casper again forgets himself, reflexively launching himself at the store’s plate glass window – and knocks a gaping hole right through it. “You idiot! Look what you done to my window”, shouts the irate shopkeeper. Casper trudges further along the road, disappointed in himself for repeatedly forgetting the loss of his powers, when a housewife hails him to fly up to rescue her cat stuck in a tree. For once, Casper remembers this is out of his present abilities, and is about to decline assistance, when he spies a child’s swing fastened to another nearby tree. “I’ll have him down in a jiffy”, Casper cheerily volunteers. Sitting in the swing, Casper rears back, and uses the forward swing to launch himself skyward, grabbing onto the branch holding the cat. Unfortunately, his grip is held onto a flimsy lower limb, which snaps off, hurling Casper into a mud puddle below. Mud splashes all over the housewife’s clean wash in the backyard – and the cat still remains unrescued. “Now I’ll have to scrub them all over again, and after all my hard work. Why, you’d think you’d be more careful….” complains the woman, as the scene dissolves to a night scene of Casper, alone in the city and sitting on a street curbside, with nowhere to turn and no one to help him. He soliloquizes to himself that if this keeps up, he’ll lose all his friends. But the judge said he had to scare someone, and he just can’t do that. “Or can I?”, Casper brightens, as an idea hatches.

Casper tries to bluff his way through an average day about town, thinking, how bad can it be? But being a mere average Joe – er, sheet – is not easy when all your human friends know you for lending a helping hand with your usual special brand of ectoplasmic magic. Casper passes a construction worker on a high girder above and exchanges greetings, then hears another shout from above, as the worker loses his footing and dangles from the girder, claiming he can’t hold on much longer. A cop on the beat says, “Quick, Casper. Fly up there and help him.” Forgetting the court sentence, Casper runs to gain flying speed, leaps into the air, and falls flat on his belly, landing on the business end of a shovel. Like a flipped tablespoon, the shovel flies into the air, hitting a board in a floor above, on top of which is a pail of hot rivets. One rivet flies out of the pail, and lands on the worker’s hands. He shouts in pain and loses his grip on the girder, falling down below, where his life is only saved by landing in a mixing vat of wet cement. As Casper asks if he’s all right, the worker replies, “A fine friend you are. Beat it!” Down the street, a shopkeeper is having trouble with his door key, and asks Casper to go through the window and open the door from the inside. Casper again forgets himself, reflexively launching himself at the store’s plate glass window – and knocks a gaping hole right through it. “You idiot! Look what you done to my window”, shouts the irate shopkeeper. Casper trudges further along the road, disappointed in himself for repeatedly forgetting the loss of his powers, when a housewife hails him to fly up to rescue her cat stuck in a tree. For once, Casper remembers this is out of his present abilities, and is about to decline assistance, when he spies a child’s swing fastened to another nearby tree. “I’ll have him down in a jiffy”, Casper cheerily volunteers. Sitting in the swing, Casper rears back, and uses the forward swing to launch himself skyward, grabbing onto the branch holding the cat. Unfortunately, his grip is held onto a flimsy lower limb, which snaps off, hurling Casper into a mud puddle below. Mud splashes all over the housewife’s clean wash in the backyard – and the cat still remains unrescued. “Now I’ll have to scrub them all over again, and after all my hard work. Why, you’d think you’d be more careful….” complains the woman, as the scene dissolves to a night scene of Casper, alone in the city and sitting on a street curbside, with nowhere to turn and no one to help him. He soliloquizes to himself that if this keeps up, he’ll lose all his friends. But the judge said he had to scare someone, and he just can’t do that. “Or can I?”, Casper brightens, as an idea hatches.

Back at the haunted house, the ghosts are rehearsing for another scare raid. A surprise visitor appears at the door – a human whom the ghost have never seen. The ghosts decide he’s a prime target to try out their new scare routines upon. Opening the door, the ghost give it their all, with their best shrieks, boos, removing their heads, etc., driving themselves to exhaustion, while the little man just stands nonchalantly, utterly unimpressed by anything he’s seeing. The ghosts collapse in a heap on the floor, winded from their efforts. “Gentlemen, my card”, the little man states, presenting a business card to the ghosts. One read of its contents, and the ghosts fly away in panic through the walls with shrieks of fright, leaving the card on the floor. “Whoopee!” shouts a familiar voice, as a mask is removed from the little man’s face, revealing Casper inside, standing on stilts. With a flash, Casper becomes transparent again, and is able to walk through the front door, stating, “Now I can go out and make friends again.” But he reappears through the door, breaking the fourth wall and speaking directly to the audience, remembering that we’re not in on what just happened. Casper reveals the contents of the card, and how he managed to scare someone after all. The card’s contents simply read, “Ghost Exterminator.”

Justice comes to television, next week.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Eddie Fagan was the leader of an Irish dance band. Fagin, the principal villain in the Dickens novel Oliver Twist, was a fence who trained boys as pickpockets; it has become an eponym for any criminal who exploits children in illegal enterprises. So “Eddie the Fagan” is part of a series of puns in “Rocket Squad” combining criminality with Irish music: a little obscure, maybe, but quite clever for all that.

The musical theme assigned to the tortoise in “A Hare-Breadth Finish” is played on the baritone saxophone in E-flat, the largest and deepest member of the saxophone family commonly played today. By the 1950s the still lower bass saxophone in B-flat had become obsolete, though one occasionally hears it in cartoons of the thirties, for example accompanying the dancing elephant in “Betty Boop’s May Party” (1933). As for the even lower contrabass and subcontrabass saxophones, very few of these instruments have ever been made, as they impose great physical demands on the players — though I was intrigued to see the sax player in the Saturday Night Live house band play a contra on the show in the eighties.

I agree that “A Hare-Breadth Finish” is a great cartoon. Poor Hubert Hare, like the Trix rabbit (whom he closely resembles), just can’t get a break.

Off topic, but there is a semi-dirty joke slipped into “Bugs’ Bonnets.” In Leon Uris’s 1953 novel “Battle Cry,” a Marine makes the mistake of referring to his rifle as a “gun.” [In the military, a “gun” is an artillery piece.] The Drill Instructor punishes him by forcing him to expose himself, holding his member in one hand and his rifle in the other, while reciting “This is my rifle/This is my gun/This one’s for fighting/This one’s for fun.” (There is a similar scene in the film “Full Metal Jacket.”) When Bugs yells at Elmer for referring to his rifle as a gun, the allusion would have been obvious to anyone who had read Uris’s best-seller.

“Rooty Toot Toot” may not have aired in the States (except on TCM when promoting their Jolly Frolics DVD), but that wasn’t true elsewhere. Growing up in Puerto Rico in the eighties, I remember translated versions of it and “The Tell-Tale Heart” airing alongside the more kid-friendly Magoo and Gerald McBoing-Boing shorts. “Cartoons are for kids, right?” was still the thinking back then, and Latin America tended to have looser standards than the US (even though PR is technically a US territory).

Casper Takes a Bow Bow and thru stock footage from it, Not Ghoulty, proved HEAVY Winston Sharples-Hal Seeger stock packes. Watch Snuffy Sniff[s 1963 KFS/Paramount cartoon “A HOSS CAN DREAM” or Felix the Cat’s T-L “THE HAUNTEED HOUSE”(Felix, Poindexter, Rock Bottom and the Professor in the middle ages)or similiar ones, the tip toe cue underneath the Trio plays. Boo!!

Spectacular Tyer footage in A Hare-Breadth Finish.

Not just the rubbery movement animation, but the zany facial expressions, and occasional glances toward the audience for no particular reason.

It’s not a REAL Terrytoon without Jim Tyer.

“Nice Doggy” (Terrytoons/Fox, The Terry Bears, 25/7/52 — Eddie Donnelly, dir.) concerns a St. Bernard pup who turns up on the Terry Bears’ doorstep one night. The cubs wants to keep it as a pet, but Papa wants nothing to do with the big, slobbering beast. After a series of misadventures Papa puts the dog in his convertible and heads for the country (“I’ll take this hound so far away, he’ll never come back!”). En route the dog snatches the cap from a motorcycle cop, who then engages in hot pursuit. The disconsolate bear cubs are overjoyed when the dog, wearing the policeman’s cap, returns to them, but wonder what could have happened to Papa. In the final scene Papa, in fetters and a striped convict’s uniform, is testifying in court: “It wasn’t my fault, your honour! I didn’t do it! I tell you it was a big dog I was trying to get rid of!”

Several drastic changes were made to “Nice Doggy” when it was adapted for the 1959 record album “TV Terrytoons Cartoon Time” (notably cutting every single one of Papa’s lines). When the motorcycle cop pulls Papa over, he recognises the dog as one whose owner had brought it to the station and asked the police to find it a good home. The cop offers a deal: if Papa will keep the dog and be kind to it, the cop won’t arrest him for speeding. Which just goes to show that most disputes can be settled out of court.

With all its innovations, ruptures and expansion of expressive and thematic boundaries, “Rooty Toot Toot” can be considered the “Citizen Kane” of the animated cartoon. By the way, there are also UPA cartoons from the McBoing Boing Show that can fit into the theme of the courtroom drama: T. Hee’s “The Trial of Zelda Belle” and Aurelius Battaglia’s “The Beanstalk Trial”.

Actually, “The Story of Anyburg U.S.A” was shown more than once on The Disney Channel in the ’90’s as it aired on one of their classic cartoon shows (“Donald’s Quack Attack” and “Mickey’s Mouse Track”).

I remember seeing ‘The Story Of Anyburg U.S.A.’ at a drive-in when I was 3 or 4. The scene where the seemingly nice people started looking evil frightened me.

The Little Audrey cartoon ‘The Sea-preme Court’ I saw only once on television when I was a kid. I don’t recall seeing any of the other cartoons mentioned in this article.

Actually, I have seen ‘Bugs’ Bonnets’ a few times.

Interesting that you have mentioned what lost prints of “Rooty Toot Toot” might have looked like in theatre screens during the 1950’s with a “UPA” logo before Columbia/Screen Gems butchered up the prints to show on television in the 1960’s. I haven’t really seen “Rooty Toot Toot” as a TV re-run, but I have seen it once in High School class on an old fashioned 16-mm film projector as a opener before the main film I was to watch in Science class as a book-and-film report (for a science project of the 1-hour film, not “Rooty Toot Toot”, which the teacher showed to the class as a special bonus opening.)

This was back in 1985, and I have only up to that point seen the “Mr. Magoo” cartoons on TV as re-runs on TV (they showed the originals from the 1950’s, the cheap TV -made knockoffs made by Henry Saperstien from 1960, and more often, “The Famous Adventures Of Mr. Magoo” re-runs from 1964. “Rooty Toot Toot”, as far as I know, was never shown as a re-run time filler in any “Magoo” slot. I don’t quite remember seeing it as part of Nickelodeon’s “Weinerville” time-fillers, either (probably because it was more adult-themed with references to cheating, drinking in a saloon, and finally, murder and a jail sentence for Frankie.)

While the 16-mm film print I saw in High School didn’t have a “UPA” logo at the close-out, instead, it had the “A Columbia Favorite” banner sliced in, followed by the Screen Gems “S From Hell” logo at the tail end of the print (I’m guessing it was a 1965 TV print, re-assigned to my High School’s film library at the time (Pontiac Northern High of Pontiac, Michigan was the school, so I don’t know if 35 years later after I seen it, if they still have the film print.)

It may have been formerly owned by a local Detroit TV station once before my school had it. (Whether it was Channels 9 or 50, I don’t know.) Channel 9 was and still is located in Windsor, Ontario, so the copy I seen may have been a Canadian print. If it was, then the film print would have been from September 1966 onward, because Canadian TV stations used the “dancing sticks” logo on their film prints from September 1963-September 1966. It was a very enjoyable cartoon, nontheless.

With ‘The Seapreme Court’, I’ve just noticed for the first time that Little Audrey was voiced by Mae Questal.

Phony Baloney, who ran afoul of the Arctic penguins’ court in “Frozen Feet”, is put on trial again in his next cartoon, “Tall Tale Teller” (Terrytoons/Fox, 2/7/54 — Connie Rasinski, dir.). As Phony stands before the judge, the arresting officer charges him with selling water from a public drinking fountain. “It’s a lie!” Phony exclaims in his Hibernian brogue. “‘Tis the Fountain of Youth I have, and I risked me neck to get it!” In a flashback he recounts a far-fetched tale of how he went to Florida and braved a condor, quicksand, crocodiles, and “a horde of ferocious Indians” before finding the Fountain of Youth — an actual drinking fountain — in the middle of the Everglades. The judge and the cop don’t believe a word of this load of blarney, but then Phony squirts them with water from the fountain, turning both of them into babies. Case dismissed!