It’s supposed to be prohibited speech to yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater. So we’ll stay within the law, opening this new series by yelling “Theater!” at a crowded fire. While it seems as if some of the mystique has worn away from modern-generation children in their attention-levels to the occupation, I can still remember the day when kids of all ages held a certain fascination for those sirens that went off in the night (before every car alarm could mimic the same effects), the flashing red lights, and those gleaming red and silver engines that carried the heroic fire fighter to the heat of the location to perform his life-saving tasks. It seemed every kid owned a push toy, wagon, or go-cart that pretended to be one of those engines, and many had play-helmets, and sometimes toy axes and hoses, to heighten the game of hero worship, and juvenile aspirations to follow in the career footsteps of these brave individuals. (Nowadays, more kids would probably aspire to become billionaire computer program designers in Silicon Valley.) Fire crews would show up at local schools to show off their equipment, and give little lectures on fire safety. Sometimes a school assembly would even get a safety film on the subject – often from the Disney educational division. There was just an overall consciousness in those bygone days that fire-fighting was cool (despite being plenty hot) – and this line of thinking rubbed off considerably upon the animation industry. From some of its earliest days, cartoons would also glorify the fireman, with frequent visits to the old volunteer and professional stations to explore life behind the scenes and in front of the hoses for these brave urban legends in their own time. Our latest trail will thus wend its way down this road of glory.

Of course, life in cartoons is not necessarily on a parity with real life. While human communities counted on their fire crews to always emerge the victor, animated hook and ladder companies were more prone to mishap and disaster, and often to causing the blaze themselves – all for the sake of developing a laugh. Add to this animation’s unique ability to breathe life into the inanimate, and the fire itself would take on its own personality, ready to do battle and outwit the fireman at every turn. For every toon fireman who extinguished a blaze, there are probably four or five who nearly became extinguished themselves in the process. So don’t bother trying to keep score, because pen and ink firemen are traditionally outgunned by a significant margin. However, if you tally their score on number of laughs rather than number of flames quenched, their point count will prove rich indeed.

Of course, life in cartoons is not necessarily on a parity with real life. While human communities counted on their fire crews to always emerge the victor, animated hook and ladder companies were more prone to mishap and disaster, and often to causing the blaze themselves – all for the sake of developing a laugh. Add to this animation’s unique ability to breathe life into the inanimate, and the fire itself would take on its own personality, ready to do battle and outwit the fireman at every turn. For every toon fireman who extinguished a blaze, there are probably four or five who nearly became extinguished themselves in the process. So don’t bother trying to keep score, because pen and ink firemen are traditionally outgunned by a significant margin. However, if you tally their score on number of laughs rather than number of flames quenched, their point count will prove rich indeed.

As usual, we have a number of unknown mysteries from the silent era to begin out survey. It’s hard to say what film may have been the first to give a flame personality, and the correct answer may never be known. So many films are lost, and sometimes little can be told from episode titles. (Paul Terry Aesop’s Fables, for example, are often known to change subjects completely two or three times in a single reel, potentially masking sequences on point for discussion.) Among some of the unknowns whose titles suggest possible relevance herewith are the following:

Bobby Bumps – “Bobby Bumps Films a Fire” (1918)

Krazy Kat – “The Smoke Eater” (10/15/25)

“Burnt Up” (5/9/27)

Aesop’s Fables – “Fire Fighters” (1926)

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit – “The Suicide Sheik” (1929) – reputed to survive but unavailable, it allegedly climaxes with Oswald saving a girl from a fire.

There are a few survivors from the era. We’ll begin with Mutt and Jeff’s Playing With Fire (9/1/26), a recently rediscovered and rescued gem. (The episode title is rather prophetic, as it is said that most of the Mutt and Jeff negatives were ultimately lost in a vault fire.) Tall Mutt and puny Jeff are spending a quiet evening at home, with Jeff appearing in the opening shot to be engaged in a game of ring toss. As the iris opens wider, we see Mutt seated in an easy chair with a pipe, blowing smoke rings. It is these rings that Jeff has been catching, making ringers with them upon the toe of Mutt’s shoe. Mutt blows one ring so high Jeff has to leap his highest to be able to catch it, and Mutt laughs. Jeff matches him for a laugh, by making another ringer – on Mutt’s nose. After chewing up the smoke as if it were an onion ring, then exgaling it again, Mutt returns to his pipe, only to find it clogged, to a point where he can’t get any action out of it. He passes it to Jeff to see what’s wrong, and Jeff takes a deep inhale, then blows into the pipe with all his might. Smoldering tobacco remnants blow out upon the floor, and suddenly, there is flame around Mutt’s chair. “FIRE!”, shouts an intertitle. Mutt begins to stomp upon the blaze, while telling Jeff to “Run for the engines.”

There are a few survivors from the era. We’ll begin with Mutt and Jeff’s Playing With Fire (9/1/26), a recently rediscovered and rescued gem. (The episode title is rather prophetic, as it is said that most of the Mutt and Jeff negatives were ultimately lost in a vault fire.) Tall Mutt and puny Jeff are spending a quiet evening at home, with Jeff appearing in the opening shot to be engaged in a game of ring toss. As the iris opens wider, we see Mutt seated in an easy chair with a pipe, blowing smoke rings. It is these rings that Jeff has been catching, making ringers with them upon the toe of Mutt’s shoe. Mutt blows one ring so high Jeff has to leap his highest to be able to catch it, and Mutt laughs. Jeff matches him for a laugh, by making another ringer – on Mutt’s nose. After chewing up the smoke as if it were an onion ring, then exgaling it again, Mutt returns to his pipe, only to find it clogged, to a point where he can’t get any action out of it. He passes it to Jeff to see what’s wrong, and Jeff takes a deep inhale, then blows into the pipe with all his might. Smoldering tobacco remnants blow out upon the floor, and suddenly, there is flame around Mutt’s chair. “FIRE!”, shouts an intertitle. Mutt begins to stomp upon the blaze, while telling Jeff to “Run for the engines.”

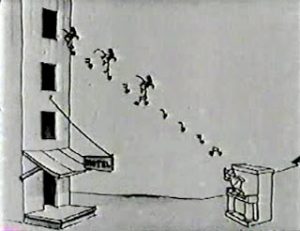

Jeff races outside to a call box on a telephone pole. The door of the box opens, with a Fireman’s head sticking out of the internal mechanism, to hang a sign on the box reading “Out to lunch.” Mutt continues to stomp on the fire inside, which begins to become elusive, changing position to avoid the pounding of Mutt’s feet. Mutt stomps more vigorously, until the fire seems to have disappeared, and Mutt puffs out his chest for a job well done. Suddenly, the flame rises again, encircling and engulfing him completely from out view. Mutt only escapes by sneaking out underneath the flame as if creeping under a curtain. And now, possibly, cartoon history is made, as the flame changes shape, developing the form of a little fiery man, who jumps back and forth, taunting Mutt. Outside, Jeff realizes he will have to take matters into his own hands, and hijacks a passing kid’s scooter as transportation down to the fire station. He finds the interior empty of personnel, but clangs on the alarm bell anyway. Down the fire pole slides no volunteers, but the station’s pumper engine – piece by piece, assembling itself as it arrives, from the boiler to the wheels. The last down the pole is the smoke, taking its place in the hole of the boiler vent. Jeff jumps into a pair of firemen’s boots, and grabs a chief’s hat – too big for his own head until he extends his ears outward to brace it. He then opens the station double doors, and beckons the engine to follow him out. The engine takes its own route, and drives in reverse through the back wall of the station, leaving Jeff behind. Jeff pursues the engine down the street, finally catching up with it by leaping upon the far end of the boiler’s smoke trail, then climbing upon the sooty puffs to the driver’s seat. Jeff registers total unfamiliarity with the engine controls, the foot pedals of which are almost out of reach for a fellow so small. He pulls at a first lever. It is an early-day ejection seat, springing him upwards and landing him into the smoke plumes again like a net. He climbs back down and tries a foot pedal. In a tracking shot, depicting a beautifully-animated dimensional view of city sidewalks and buildings passing by, we see the engine commence a 360-degree spin as it continues down the street. More pushes and tugs at controls, and the driver’s cab disconnects from the boiler, each section of the vehicle zig-zagging down the street independently. Seeing the boiler section about to pass him, Jeff leaps upon it, then attempts to pull it like a beast of burden to catch up with the driver’s cab. The smoke trail gets into the gag of Jeff as steed, by transforming into the shape of a hand, snapping a prodding whip above Jeff’s head. Both halves of the vehicle reach an intersection, where they demolish a passing hay wagon on the cross-street. The old driver stands up among what appears to be a load of spilled hay, shaking his fist at Jeff, then gathers up what we thought was the haystack – turning out instead to be his own long grizzled beard. Back to Jeff, who has picked up a passenger in the collision – the farmer’s horse. All the better, thinks Jeff, hitching the boiler to the horse instead of himself, and abandoning the chase after the engine cab, to take the boiler back to Mutt.

Jeff races outside to a call box on a telephone pole. The door of the box opens, with a Fireman’s head sticking out of the internal mechanism, to hang a sign on the box reading “Out to lunch.” Mutt continues to stomp on the fire inside, which begins to become elusive, changing position to avoid the pounding of Mutt’s feet. Mutt stomps more vigorously, until the fire seems to have disappeared, and Mutt puffs out his chest for a job well done. Suddenly, the flame rises again, encircling and engulfing him completely from out view. Mutt only escapes by sneaking out underneath the flame as if creeping under a curtain. And now, possibly, cartoon history is made, as the flame changes shape, developing the form of a little fiery man, who jumps back and forth, taunting Mutt. Outside, Jeff realizes he will have to take matters into his own hands, and hijacks a passing kid’s scooter as transportation down to the fire station. He finds the interior empty of personnel, but clangs on the alarm bell anyway. Down the fire pole slides no volunteers, but the station’s pumper engine – piece by piece, assembling itself as it arrives, from the boiler to the wheels. The last down the pole is the smoke, taking its place in the hole of the boiler vent. Jeff jumps into a pair of firemen’s boots, and grabs a chief’s hat – too big for his own head until he extends his ears outward to brace it. He then opens the station double doors, and beckons the engine to follow him out. The engine takes its own route, and drives in reverse through the back wall of the station, leaving Jeff behind. Jeff pursues the engine down the street, finally catching up with it by leaping upon the far end of the boiler’s smoke trail, then climbing upon the sooty puffs to the driver’s seat. Jeff registers total unfamiliarity with the engine controls, the foot pedals of which are almost out of reach for a fellow so small. He pulls at a first lever. It is an early-day ejection seat, springing him upwards and landing him into the smoke plumes again like a net. He climbs back down and tries a foot pedal. In a tracking shot, depicting a beautifully-animated dimensional view of city sidewalks and buildings passing by, we see the engine commence a 360-degree spin as it continues down the street. More pushes and tugs at controls, and the driver’s cab disconnects from the boiler, each section of the vehicle zig-zagging down the street independently. Seeing the boiler section about to pass him, Jeff leaps upon it, then attempts to pull it like a beast of burden to catch up with the driver’s cab. The smoke trail gets into the gag of Jeff as steed, by transforming into the shape of a hand, snapping a prodding whip above Jeff’s head. Both halves of the vehicle reach an intersection, where they demolish a passing hay wagon on the cross-street. The old driver stands up among what appears to be a load of spilled hay, shaking his fist at Jeff, then gathers up what we thought was the haystack – turning out instead to be his own long grizzled beard. Back to Jeff, who has picked up a passenger in the collision – the farmer’s horse. All the better, thinks Jeff, hitching the boiler to the horse instead of himself, and abandoning the chase after the engine cab, to take the boiler back to Mutt.

Meanwhile, Mutt is finding his own hands full. The wily flame-man is pursuing him around the living room. Mutt tries to throw some water upon him, bit the fire-man opens his mouth, takes in the fluid, then spits it out at Mutt, followed by giving Mutt the horse laigh. The flame jumps onto Mutt’s bed, and engages in some acrobatic evasions of Mutt by bouncing between bed and ceiling light fixture. Between whiles, it engages in a game of peek-a-boo, giving Mutt intermittent touches in the rear end for a hotseat, and even disappearing up Mutt’s pantleg, then appearing out his sleeve to give him the raspberry. Mutt has finally had enough, and, spotting an electric fan, turns it upon the flame. Instead of spreading the fire by the wind force, the fire develops sneezes and a case of the chills, with ice cubes developing around its feet. It suddenly expires completely, disappears – then reappears a moment later with wings and a harp, in the guise of an angel, and dissolves into the ether, never to be seen again. (Perhaps Tex Avery remembered this gag, as will be seen in a subsequent chapter of this series.) Mutt dances victoriously, then ponders, “I wonder what happened to Jeff?” Jeff finally arrives with the engine, chops a hole in Mutt’s door, then enters with the fire hose. Seeing a view from the rear of Mutt’s easy chair, Jeff sees a steady stream of smoke rising from it, and presumes the fire is still where he left it. Jeff turns the high-pressure hose upon the chair, knocking it over to reveal Mutt, back to his smoking, and now getting drenched. Mutt rises, tosses Jeff into a corner, and gives Jeff a dose of his own medicine, turning the hose upon him. From out of the stream of water hop Jeff’s fireman’s boots and hat, and the rest of his outfit, which all run for the hills independent of their owner. Mutt turns down the spray of water, to reveal Jeff, butt naked. Jeff solves his momentary embarrassment by grabbing a portion of the trickling water stream, and somehow wrapping it around him as the shape-equivalent of a grass skirt, then laughs. Mutt thinks the joke poor, and deluges Jeff from view again, for the fade out. A well-timed and nicely animated early classic, non-stop in its humor, that was likely remembered in the industry, despite ultimately being almost lost to time.

Lacking in a musical score on presently-circulating foreign print, Walt Disney’s Alice the Fire Fighter (10/18/26) is revealed to be unusually leisurely-paced for a fire cartoon, lingering much too long on each individual gag to maintain any sense of urgency or excitement. Disney seems to have had a footage quota to meet, and not enough gag material to meet it comfortably, so stretches many shots far beyond what they’re worth. Alice doesn’t have too much to do, playing a mostly passive role as fire chief in a relatively small number of shots, while Julius and a crew of look-alike cats handle the real work.

Lacking in a musical score on presently-circulating foreign print, Walt Disney’s Alice the Fire Fighter (10/18/26) is revealed to be unusually leisurely-paced for a fire cartoon, lingering much too long on each individual gag to maintain any sense of urgency or excitement. Disney seems to have had a footage quota to meet, and not enough gag material to meet it comfortably, so stretches many shots far beyond what they’re worth. Alice doesn’t have too much to do, playing a mostly passive role as fire chief in a relatively small number of shots, while Julius and a crew of look-alike cats handle the real work.

Two characters yell “Fire” on opposite sides of a tall hotel tower, as others stream out of its ground floor, and still others in upper story windows call for help. No flames are seen in this picture – only puffs of black smoke. In the town center, a mouse tugs on the rope of a community alarm bell, then loses his grip on the rope, sending the bell into a spin around its axle pole to continue to ring on its own, while the mouse, unable to reach the twirling rope, just joins in with yells. Even a church belfry loudly clangs an alarm, the visible word “CLANG” entering the window of a local firehouse. Everyone’s a sound sleeper, and it takes several more clangs to finally arouse the crew – an endless repeating cycle of cats. At the foot of each of three beds lies an upside-down stack of fireman’s hats, between the beds and a hole to the floor below. From under the covers of each bed emerge the endless stream of cats, each leaping to land upside down in the hat stack, bounce off wearing appropriate head gear, and leap down the hole. Instead of a fire pole, the cats ride an unnecessarily corkscrewed slide. Below, a line of self-propelled trousers races to meet them as they flip off the end of the slide, landing squarely in the slacks to complete their uniform. The fire horse also has a rapid dressing regimen. His harnesses are suspended from ropes above the floor, and below them rest his horseshoes on the ground, spread appropriately apart to match the spacing of his feet. The horse jumps upward into the harness, positions his legs to match the position of the shoes, then releases the rope holding the harness straps, dropping him squarely onto all four shoes. (We’ll see similar versions of this trope repeated again in later films.) Another repeating cycle shows an almost endless line of fire trucks leaving the station, finally followed by the pumper and hook and ladder, at which point the building deflates like a flattened balloon.

Back at the hotel, we see what may be the earliest surviving appearance of what I will call a “bridging” trope – an impossible means of providing an escape ramp for the characters from the burning building. A small dog lugs a large upright piano out of the hotel lobby, then plays a series of notes that visibly rise into the air in the shapes they would appear as on a music sheet. The assembled notes form a staircase to an upper-story window, and another repeating cycle of characters race down the notes from out the window. The firemen arrive, and a cat rides atop the extension ladder – a stand-up model like a painter would use, detached from the engine, which runs on its poles under its own power to a point adjacent to the building. For no apparent reason, the ladder sets itself several feet away from the building’s windows, so that the cat is uable to reach the people needing rescuing. He outstretches his arms while another cat attempts to brace the ladder extension from below – and the extended ladder section pivots over the top brace to form a teeter=totter between the two cats. When the lower cat finally manages to return to the ground ro brace the ladder again, the upper cat calls to other members of the crew to solve the problem – by sliding the entire hotel building within reach of the ladder. The hose crew arrives, but can’t get more than a trickle of drops to come out. So, instead of a bucket brigade, one cat laboriously fills a pail repeatedly with water, scales the ladder, and tosses it on the fire. By the third trip, he is so tired and perspiring, that instead of tossing the water on the fire, he drinks it himself. A mouse is forced to leap from a high ledge toward a pair of firemen holding a net. The firemen struggle to position the net at the proper point to make the catch, miscalculate entirely, and let the mouse bounce off his head from the pavement before catching him on the rebound, then carry him off. Another possible earliest appearance of a “bridging” gag somehow has the cats finally obtain hose pressure and aim a stream of water at one of the upper windows, causing the hotel guests to ride down the stream of fluid like a waterslide. The final, overly stretched sequence, has a female cat almost overcome by smoke inhalation, needing rescue above. Julius the cat tries climbing a tall drainpipe, but it detaches from the building and plops him back upon the ground. He hits upon an idea from the puffs of smoke emitting from the boiler of the pumper engine, and positions the vehicle below the ledge where the female cat has fainted. Julius climbs upon the engine, and hops atop one of the rising smoke clouds. On the way up, he grabs the girl cat, then Alice provides her only active assist, by pulling a lever on the engine that magically sends the smoke clouds unto reverse gear, bringing Julius back down. The girl revives, and the two kiss shamelessly, as Alice and the crowd cheer, for the iris out.

Back at the hotel, we see what may be the earliest surviving appearance of what I will call a “bridging” trope – an impossible means of providing an escape ramp for the characters from the burning building. A small dog lugs a large upright piano out of the hotel lobby, then plays a series of notes that visibly rise into the air in the shapes they would appear as on a music sheet. The assembled notes form a staircase to an upper-story window, and another repeating cycle of characters race down the notes from out the window. The firemen arrive, and a cat rides atop the extension ladder – a stand-up model like a painter would use, detached from the engine, which runs on its poles under its own power to a point adjacent to the building. For no apparent reason, the ladder sets itself several feet away from the building’s windows, so that the cat is uable to reach the people needing rescuing. He outstretches his arms while another cat attempts to brace the ladder extension from below – and the extended ladder section pivots over the top brace to form a teeter=totter between the two cats. When the lower cat finally manages to return to the ground ro brace the ladder again, the upper cat calls to other members of the crew to solve the problem – by sliding the entire hotel building within reach of the ladder. The hose crew arrives, but can’t get more than a trickle of drops to come out. So, instead of a bucket brigade, one cat laboriously fills a pail repeatedly with water, scales the ladder, and tosses it on the fire. By the third trip, he is so tired and perspiring, that instead of tossing the water on the fire, he drinks it himself. A mouse is forced to leap from a high ledge toward a pair of firemen holding a net. The firemen struggle to position the net at the proper point to make the catch, miscalculate entirely, and let the mouse bounce off his head from the pavement before catching him on the rebound, then carry him off. Another possible earliest appearance of a “bridging” gag somehow has the cats finally obtain hose pressure and aim a stream of water at one of the upper windows, causing the hotel guests to ride down the stream of fluid like a waterslide. The final, overly stretched sequence, has a female cat almost overcome by smoke inhalation, needing rescue above. Julius the cat tries climbing a tall drainpipe, but it detaches from the building and plops him back upon the ground. He hits upon an idea from the puffs of smoke emitting from the boiler of the pumper engine, and positions the vehicle below the ledge where the female cat has fainted. Julius climbs upon the engine, and hops atop one of the rising smoke clouds. On the way up, he grabs the girl cat, then Alice provides her only active assist, by pulling a lever on the engine that magically sends the smoke clouds unto reverse gear, bringing Julius back down. The girl revives, and the two kiss shamelessly, as Alice and the crowd cheer, for the iris out.

A goodly percentage of the thought-lost Disney Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon, Empty Socks (12/12/27) has finally surfaced. Despite a continuity break in the middle and a clipped ending, it is tantalizing to find a new holiday title from animation’s Golden era. Oswald is playing Santa for the cat children of an orphanage, where a matron cat (Ortensia?) reads “The Night Before Christmas” to the kids as they rest in a unique communal bed curved like a “U” around one-half of the room. (Wonder where you find sheets and blankets for such a furnishing?) Outside, Oswald dons the requisite costume and whiskers, while his horse is given a fake set of reindeer antlers. With a considerable amount of limb contortion, Oswald’s horse provides support to get the rabbit and his load of toys up to the chimney. The chimney is not, however, the conventional open-mouth model, but provides its venting only through a small pair of metal pipes. Oswald can’t get either his feet or his head through the small tubes, so has to contort himself to reform his entire body into a compressed narrow cylinder, then drop himself down the pipe. Amazingly, the toys fit too without breaking. Then, more amazingly, the horse follows (though we never see the compression of his body on camera). The horse makes so much noise, Oswald and Ortensia are afraid he’ll wake the kids. They needn’t worry, as the kids have been following Ortensia ever since she left the bedroom, and are peering in at the keyhole and transom. Oswald sets up a Christmas tree, as if he were opening an umbrella. One of the kids looks on from a staircase above, but tumbles down, bouncing on his tail extended through his pajama drop-seat. Here, the film abruptly breaks, skipping to a sequence where the kiss are playing with Oswald’s toys – particularly a toy fire engine. To make its use seem more appropriate, other kittens have set a chair afire in the room.

A goodly percentage of the thought-lost Disney Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon, Empty Socks (12/12/27) has finally surfaced. Despite a continuity break in the middle and a clipped ending, it is tantalizing to find a new holiday title from animation’s Golden era. Oswald is playing Santa for the cat children of an orphanage, where a matron cat (Ortensia?) reads “The Night Before Christmas” to the kids as they rest in a unique communal bed curved like a “U” around one-half of the room. (Wonder where you find sheets and blankets for such a furnishing?) Outside, Oswald dons the requisite costume and whiskers, while his horse is given a fake set of reindeer antlers. With a considerable amount of limb contortion, Oswald’s horse provides support to get the rabbit and his load of toys up to the chimney. The chimney is not, however, the conventional open-mouth model, but provides its venting only through a small pair of metal pipes. Oswald can’t get either his feet or his head through the small tubes, so has to contort himself to reform his entire body into a compressed narrow cylinder, then drop himself down the pipe. Amazingly, the toys fit too without breaking. Then, more amazingly, the horse follows (though we never see the compression of his body on camera). The horse makes so much noise, Oswald and Ortensia are afraid he’ll wake the kids. They needn’t worry, as the kids have been following Ortensia ever since she left the bedroom, and are peering in at the keyhole and transom. Oswald sets up a Christmas tree, as if he were opening an umbrella. One of the kids looks on from a staircase above, but tumbles down, bouncing on his tail extended through his pajama drop-seat. Here, the film abruptly breaks, skipping to a sequence where the kiss are playing with Oswald’s toys – particularly a toy fire engine. To make its use seem more appropriate, other kittens have set a chair afire in the room.

Animation of the flames is notable, as it is the most realistic seen to date, and accomplished without the use of drawn outlines, painting each cel in stark white paint with no ink borderlines (I am uncertain if any exposure tricks are yet used to make the white register brighter than surrounding grays). While competing studios in the next two titles listed below would continue to use harsh black outlines around fire, Disney would refine these techniques by his next production listed below, by transmuting backgrounds from day to night settings, , giving his non-outlined flames even a greater appearance of brightness. Another kitten hooks up the fire hose to the sink, and turns on the water. Nothing seems to come out the other end, and the cat holding the nozzle looks Into the tube to see what is the holdup. He gets blasted in the face, and the hose breaks loose and runs amok in a well-animated repeating cycle that dimensionally manipulates the hose at varying distances from the camera. Once the water is finally brought under control, the flame surprisingly does not go out, but reacts in anger at being squirted, developing fiery hands that pinch at the tail of the cat who squirted it. The other orphans run from the building as the rising flames engulf the living room. Oswald also emerges (now minus his suit and whiskers – did the kids discover his identity?). From nowhere, he discovers a hose already hooked up to a fire hydrant, and drags the hose nozzle within range of the orphanage. Nearby is parked a gasoline tanker truck, and the devilish kids get an idea. In a situation predicting Donald Duck’s later production “Fire Chief”, the kids unfasten the hose from the hydrant, and hook it to the release valve on the rear of the tanker. (Don’t they realize they’re putting their own home in jeopardy? Oh, well, anything for a mischievous laugh.) Oswald signals them to start the water, and they open the gasoline valve. “BOOM!” And that’s pretty much where the existing footage ends, as Oswald barely has time to land upon the ground from the explosion, while the kittens laugh uproariously.

The Smoke Scream (Pat Sullivan, 1/8/28) finds Felix the Cat with a new owner – a bewhiskered old-timer not dissimilar in appearance from Farmer Al Falfa, excepting a somewhat longer set of whiskers and a pair of spectacles. The old gent is fond of pipe-smoking – a habit which drives his burly wife crazy, sending her into coughing jags every time she inhales the secondhand smoke. The wife approaches the old man to accuse him of smoking in the house, but the man attempts to escape the blame by passing the pipe to Felix, having no moral qualms about framing his pet for the rap. The wife sees through his ruse when the man begins to turn black, and is forced to exhale, releasing a large cloud of tobacco smoke he had been holding in his cheeks. The wife tosses the pipe out the window. Felix, helpful to a fault in spite of being framed, removes the speaker horn from the couple’s radio set, transforming its bell into an even larger pipe. Gramps is happy as a clam, until the wife gets another whiff of the even stronger smoke. She re-enters the room, and gives the old-timer a resounding shellacking, then tosses the radio horn out the window too. With no more substitutes to turn to for a quiet smoke, the old timer gives up, yawns, and falls asleep. A beam of sunlight streams in at the window, passing through the lens of one of the man’s spectacles, which focuses the sunlight directly upon the tip of the man’s beard. Suddenly the man has all the smoking sensations he can possibly handle, as his beard is set on fire, emitting more clouds than a steam locomotive. Felix tries to douse the flames, including by dumping a fishbowl on the man’s head, bit all efforts are of no use. The man races blindly outside, running aimlessly in all directions from the smoke he cannot escape. Felix is unable to keep up, and knows he needs assistance to continue a rescue. Spotting a fire station down the block, Felix races upstairs to the firemen’s quarters, only to find them all asleep. Despite yowling his loudest yowls, and ringing the fire bell, the crew remain sawing wood and producing ZZZZZ’s in the air. If you want a thing done right, do it yourself. Felix grabs a fireman’s hat, leaps into a pair of boots, and slides down the pole, landing in the driver’s seat of the fire engine. A crowd begins to gather outside the door of the station as they hear the engine warming up, waiting to see the vehicle’s emergence. They miss it entirely, as Felix crashes the vehicle through and out the side wall of the station. He pursues the old man, who remains running at a speed Felix can only match but not overtake.

The Smoke Scream (Pat Sullivan, 1/8/28) finds Felix the Cat with a new owner – a bewhiskered old-timer not dissimilar in appearance from Farmer Al Falfa, excepting a somewhat longer set of whiskers and a pair of spectacles. The old gent is fond of pipe-smoking – a habit which drives his burly wife crazy, sending her into coughing jags every time she inhales the secondhand smoke. The wife approaches the old man to accuse him of smoking in the house, but the man attempts to escape the blame by passing the pipe to Felix, having no moral qualms about framing his pet for the rap. The wife sees through his ruse when the man begins to turn black, and is forced to exhale, releasing a large cloud of tobacco smoke he had been holding in his cheeks. The wife tosses the pipe out the window. Felix, helpful to a fault in spite of being framed, removes the speaker horn from the couple’s radio set, transforming its bell into an even larger pipe. Gramps is happy as a clam, until the wife gets another whiff of the even stronger smoke. She re-enters the room, and gives the old-timer a resounding shellacking, then tosses the radio horn out the window too. With no more substitutes to turn to for a quiet smoke, the old timer gives up, yawns, and falls asleep. A beam of sunlight streams in at the window, passing through the lens of one of the man’s spectacles, which focuses the sunlight directly upon the tip of the man’s beard. Suddenly the man has all the smoking sensations he can possibly handle, as his beard is set on fire, emitting more clouds than a steam locomotive. Felix tries to douse the flames, including by dumping a fishbowl on the man’s head, bit all efforts are of no use. The man races blindly outside, running aimlessly in all directions from the smoke he cannot escape. Felix is unable to keep up, and knows he needs assistance to continue a rescue. Spotting a fire station down the block, Felix races upstairs to the firemen’s quarters, only to find them all asleep. Despite yowling his loudest yowls, and ringing the fire bell, the crew remain sawing wood and producing ZZZZZ’s in the air. If you want a thing done right, do it yourself. Felix grabs a fireman’s hat, leaps into a pair of boots, and slides down the pole, landing in the driver’s seat of the fire engine. A crowd begins to gather outside the door of the station as they hear the engine warming up, waiting to see the vehicle’s emergence. They miss it entirely, as Felix crashes the vehicle through and out the side wall of the station. He pursues the old man, who remains running at a speed Felix can only match but not overtake.

The man approaches a tall multi-story office building, and vanishes into its front door. Well, he doesn’t actually vanish, as we are able to follow his progress in the many windows of the structure, as he runs through one floor traveling in one direction, then through the next story in reverse direction, and so on up to the top floor, leaving the building filled with billows of smoke still endlessly emitting from his beard. Overcome with the foul air, other occupants of the building begin clamoring to the windows for a breath of fresh oxygen, waving toward the ground for anyone to help. Felix’s engine arrives, and he surveys the situation with dismay, wondering how he will ever reach the old man and save all these other people as well. He spots a hydrant nearby, but cannot locate a hose on the unprepared fire engine to hook to it. Instead, Felix attaches the tip of his magic tail to the hydrant connection, pulls, and stretches his tail several yards until he has reached a position close to the foot of the building. Them, he disconnects his tail from his body at its roots, and uses it as a hose to spray the smoky windows. He struggles with his aim to guide the water to the topmost windows of the structure – but does succeed in aiming the stream under the ledge of one of the upper windows, repeating the Alice gag by producing an arc of water which the building occupants use as a bridge to descend to the ground. When Felix is confident the office personnel have escaped, he disconnects his tail from the hydrant, inserts its root back into his body, and swishes it a few times just to make sure it still works. Oh, oh, he acted too soon. There’s still a fat woman in an upper window, hollering for someone to help her. Probably figuring she is too heavy for the water bridge anyway, Felix does not re-employ his tail again, but instead finds the discarded insides of a sofa spring, with padded cushion still attached above the metal framework. He places it under the lady’s window, calling for her to jump. The woman leaps – but the spring is so strong, it merely launches her right back into the window again. Felix has no choice but to enter the smoke-filled building himself through a lower-story window, and try to work his way upstairs. He wanders through smoke-filled corridors, the air so thick that all that can be seen of him is a silhouette, froping in the darkness. His trek goes on and on. Finally, he emerges from the building’s front door – not carrying the woman, but having somehow finally located the old man, removing the source of smoke from the building. He deposits the man into a nearby stream for a complete immersion, and the smoke clouds begin to dissipate. The man rises from the water a few feet away, revealing that his beard is out, disconnected from the smoke plume, which rises in its last throes from the middle of the stream. However, the smoke pulls a surprise, and jumps from the water’s surface, to settle upon the tip of Felix’s tail, setting it in fire. The film ends with Felix incurring life’s usual habit of handing him hard luck at every turn, running helter-skelter as did the old man, in hopeless effort to outrun the chugging smoke billowing from his rear, for the iris out.

The man approaches a tall multi-story office building, and vanishes into its front door. Well, he doesn’t actually vanish, as we are able to follow his progress in the many windows of the structure, as he runs through one floor traveling in one direction, then through the next story in reverse direction, and so on up to the top floor, leaving the building filled with billows of smoke still endlessly emitting from his beard. Overcome with the foul air, other occupants of the building begin clamoring to the windows for a breath of fresh oxygen, waving toward the ground for anyone to help. Felix’s engine arrives, and he surveys the situation with dismay, wondering how he will ever reach the old man and save all these other people as well. He spots a hydrant nearby, but cannot locate a hose on the unprepared fire engine to hook to it. Instead, Felix attaches the tip of his magic tail to the hydrant connection, pulls, and stretches his tail several yards until he has reached a position close to the foot of the building. Them, he disconnects his tail from his body at its roots, and uses it as a hose to spray the smoky windows. He struggles with his aim to guide the water to the topmost windows of the structure – but does succeed in aiming the stream under the ledge of one of the upper windows, repeating the Alice gag by producing an arc of water which the building occupants use as a bridge to descend to the ground. When Felix is confident the office personnel have escaped, he disconnects his tail from the hydrant, inserts its root back into his body, and swishes it a few times just to make sure it still works. Oh, oh, he acted too soon. There’s still a fat woman in an upper window, hollering for someone to help her. Probably figuring she is too heavy for the water bridge anyway, Felix does not re-employ his tail again, but instead finds the discarded insides of a sofa spring, with padded cushion still attached above the metal framework. He places it under the lady’s window, calling for her to jump. The woman leaps – but the spring is so strong, it merely launches her right back into the window again. Felix has no choice but to enter the smoke-filled building himself through a lower-story window, and try to work his way upstairs. He wanders through smoke-filled corridors, the air so thick that all that can be seen of him is a silhouette, froping in the darkness. His trek goes on and on. Finally, he emerges from the building’s front door – not carrying the woman, but having somehow finally located the old man, removing the source of smoke from the building. He deposits the man into a nearby stream for a complete immersion, and the smoke clouds begin to dissipate. The man rises from the water a few feet away, revealing that his beard is out, disconnected from the smoke plume, which rises in its last throes from the middle of the stream. However, the smoke pulls a surprise, and jumps from the water’s surface, to settle upon the tip of Felix’s tail, setting it in fire. The film ends with Felix incurring life’s usual habit of handing him hard luck at every turn, running helter-skelter as did the old man, in hopeless effort to outrun the chugging smoke billowing from his rear, for the iris out.

Fiery Firemen (Winkler/Universal, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, 10/15/28 – Isadore Freleng/Rudolf Ising, anim.) – One of the Winkler Oswalds produced between the Disney and Lantz runs. Oswald and a camel bunk together in the bedroom of the fire station. In town, another tower is on fire. It is significant to note the relative sophistication of this shot versus the tower seen in the Alice comedy discussed above, including flames and many more characters. While this is an isolated shot among many more conventional ones, it demonstrates how much the industry was developing over a few short years, when it wanted to get fancy. In a typical Rudolf Ising touch, a character races straight at the camera, the lens proceeding down his throat, from which appears the onscreen word, “FIRE!” At the station house, Oswald’s brass bed develops a face, and attempts to yell and rouse its occupants from sleep. Oswald and the camel slowly open their eyes and yawn, then nod off to sleep again. The bed goes through gestures of desperation as if tearing out its hair, then solves the problem by itself leaping upon the fire pole, carrying its occupants with it downstairs, and bouncing them out upon the ground as it reaches the pole’s base. Oswald and the camel grab their hats off the wall, and the bed tries to join the action too by picking up a fire axe, until Oswald and the camel scold it and order it to get back upstairs where it belongs.

Fiery Firemen (Winkler/Universal, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, 10/15/28 – Isadore Freleng/Rudolf Ising, anim.) – One of the Winkler Oswalds produced between the Disney and Lantz runs. Oswald and a camel bunk together in the bedroom of the fire station. In town, another tower is on fire. It is significant to note the relative sophistication of this shot versus the tower seen in the Alice comedy discussed above, including flames and many more characters. While this is an isolated shot among many more conventional ones, it demonstrates how much the industry was developing over a few short years, when it wanted to get fancy. In a typical Rudolf Ising touch, a character races straight at the camera, the lens proceeding down his throat, from which appears the onscreen word, “FIRE!” At the station house, Oswald’s brass bed develops a face, and attempts to yell and rouse its occupants from sleep. Oswald and the camel slowly open their eyes and yawn, then nod off to sleep again. The bed goes through gestures of desperation as if tearing out its hair, then solves the problem by itself leaping upon the fire pole, carrying its occupants with it downstairs, and bouncing them out upon the ground as it reaches the pole’s base. Oswald and the camel grab their hats off the wall, and the bed tries to join the action too by picking up a fire axe, until Oswald and the camel scold it and order it to get back upstairs where it belongs.

Oswald and the camel race outside into a small supply shed. Having no engine, the horse emerges on roller skates, supporting one end or a long ladder, atop which rests a coil of hose. Oswald is on the other end of the ladder, not holding it up, but somehow attempting to steer it by shifting his body weight – doing some more Ising-style camera tricks by swiveling toward and away from camera viewpoint. At the burning building, an elephant experiences a rocky descent. She first leaps into a pair of panties her size on a clothesline extending to the next building, and attempt to use it as a buoy to pull herself to the other building. The flames seem to have spread to both structures, and a jet of flames licks her tail, bouncing her upwards and detaching the panties from the clothespins. The elephant nevertheless sails downward gracefully, using the panties as a parachute – until another flare of flames burns the panties to cinders. She bounces the rest of the way down, ricocheting from the awnings of one building to the other’s. Meanwhile, our fire crew is zig-zagging between rocks in the road, Then the camel trips, leaving Oswald and the equipment sprawled on the ground. “I faw down”, says the camel in subtitle. Oswald gathers up the hose by tying it around the camel’s waist, then cranking the camel’s tail like the handle of a well, reeling the hose in around the camel’s rotating torso. Without the ladder, they race to the fire. The camel skids to a stop in front of the burning building, rolling sideways to unroll the hose. Oswald produces his own portable hydrant from out of a pocket, but before he can get started with the water, the shouted word “Help” appears in the air above him. The “P” breaks apart, forming an arrow pointing upwards – then transforms into a pair of wings, rising upwards and dragging the rest of the letters and Oswald along. On a ledge above, Oswald finds a row of stranded mice. Oswald dashes into their bathroom, producing a large tube of toothpaste. Oswald drops a line of paste to the ground for the mice to slide down, then, upon hearing a further call for help from the next building, squirts another line of paste over to the opposite building ledge, for him to climb over to investigate. I never realized a camel could be a marsupial, bit the camel produces a pouch pocket from nowhere, and, cranking his tail, extends from the pocket a second ladder from nowhere, which rises to Oswald’s level. Then, the camel is able to remove the ladder from his own pocket to climb it. Inside the second building, they find a female hippo overcome from smoke. The two fire fighters struggle to lift her, the camel almost crushed under her weight. Oswald climbs out the window, and tugs the hippo out by the tail to the waiting ladder. After three steps, her weight causes the rungs of the ladder to give way, Oswald painfully falling through each lower rung in succession on a rapid trip toward the ground. Ozzie and the hippo break a large hole in the sidewalk below – but rise a moment later from a nearby underground freight elevator, Oswald holding the safe hippo aloft in one hand, and striking a heroic pose for the crowd (which for all intents and purposes looks like the future face of Bosko) for the iris out.

Oswald and the camel race outside into a small supply shed. Having no engine, the horse emerges on roller skates, supporting one end or a long ladder, atop which rests a coil of hose. Oswald is on the other end of the ladder, not holding it up, but somehow attempting to steer it by shifting his body weight – doing some more Ising-style camera tricks by swiveling toward and away from camera viewpoint. At the burning building, an elephant experiences a rocky descent. She first leaps into a pair of panties her size on a clothesline extending to the next building, and attempt to use it as a buoy to pull herself to the other building. The flames seem to have spread to both structures, and a jet of flames licks her tail, bouncing her upwards and detaching the panties from the clothespins. The elephant nevertheless sails downward gracefully, using the panties as a parachute – until another flare of flames burns the panties to cinders. She bounces the rest of the way down, ricocheting from the awnings of one building to the other’s. Meanwhile, our fire crew is zig-zagging between rocks in the road, Then the camel trips, leaving Oswald and the equipment sprawled on the ground. “I faw down”, says the camel in subtitle. Oswald gathers up the hose by tying it around the camel’s waist, then cranking the camel’s tail like the handle of a well, reeling the hose in around the camel’s rotating torso. Without the ladder, they race to the fire. The camel skids to a stop in front of the burning building, rolling sideways to unroll the hose. Oswald produces his own portable hydrant from out of a pocket, but before he can get started with the water, the shouted word “Help” appears in the air above him. The “P” breaks apart, forming an arrow pointing upwards – then transforms into a pair of wings, rising upwards and dragging the rest of the letters and Oswald along. On a ledge above, Oswald finds a row of stranded mice. Oswald dashes into their bathroom, producing a large tube of toothpaste. Oswald drops a line of paste to the ground for the mice to slide down, then, upon hearing a further call for help from the next building, squirts another line of paste over to the opposite building ledge, for him to climb over to investigate. I never realized a camel could be a marsupial, bit the camel produces a pouch pocket from nowhere, and, cranking his tail, extends from the pocket a second ladder from nowhere, which rises to Oswald’s level. Then, the camel is able to remove the ladder from his own pocket to climb it. Inside the second building, they find a female hippo overcome from smoke. The two fire fighters struggle to lift her, the camel almost crushed under her weight. Oswald climbs out the window, and tugs the hippo out by the tail to the waiting ladder. After three steps, her weight causes the rungs of the ladder to give way, Oswald painfully falling through each lower rung in succession on a rapid trip toward the ground. Ozzie and the hippo break a large hole in the sidewalk below – but rise a moment later from a nearby underground freight elevator, Oswald holding the safe hippo aloft in one hand, and striking a heroic pose for the crowd (which for all intents and purposes looks like the future face of Bosko) for the iris out.

An honorable mention goes to Columbia’s Ratskin (Charles Mintz, Krazy Kat, 8/15/29 – Ben Harrison, Manny Gould, dir.), which, while having nothing to do with an engine company, may be the earliest use in a sound cartoon of anthropomorphic flame. Pioneer Krazy Kat is captured by Indians (the picture’s title is a wordplay upon Paramount’s recent part-color feature success, “Redskin”). He is tied to a tree stump, and a fire is lit around his feet. An Indian feeds the flames – literally – as the fire develops a face and mouth, which it opens wide to receive deposits of fresh logs, chewing them up ravenously. After taking several painful touches of the fire to his tail, Krazy hits upon an idea, and begins blowing at the flames below him. In a direct lift from Mutt and Jeff’s “Playing With Fire”, the flame shudders at the chill air, clapping its hands together to keep warm and developing sneezes, and eventually goes out. This is not the only time where a Mutt and Jeff gag would reappear in a Krazy Kat (another such instance being a mysteriously reused sequence of animation in a subway, shared in common between Krazy Kat’s “The Broadway Malady” and Mutt and Jeff’s “The Globe Trotters”) – suggesting that there was some shared personnel between the two production companies, who brought over their work to Mintz.

As the dawn of sound shone its first sunbeams through animated celluloid, Mickey Mouse was among the first to bring the thrill of the sound of a siren to his avid viewers.

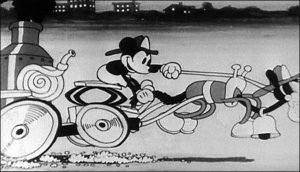

The Fire Fighters (Disney/Columbia, 6/20/30 – Burt Gillett, dir.) gives one a partial sense of deja vi, as it is quickly apparent that it is a reworking of many principal sequences of “Alice the Fire Fighter”. However, the capable direction of Burt Gillett proves that by this time, Disney has gotten his timing down, and the pacing of all gags is brisk and drama-evoking, also aided greatly by a lively musical underscore (was this still Carl Stalling?) heightening the action. With substantial improvement in use of darker dramatic greys and detailed backgrounds, we open on a night shot of the firehouse, then dissolve to its interior, where a large crew of characters of various species (each one in their own bed rather than doubling or tripling up for endless cycles of characters) snores away. There is a bit of cross-pollenation from Universal here, as the snoring animation almost matches precisely the work of Freleng and Ising in “Fiery Fireman”’s opening shot – something that shouldn’t have been in Disney’s stock footage. Fire Chief Mickey has a bed at the head of the line, and the mouse also snores away the evening, almost swallowing a spider dangling from a web above him on every inhale. Horace Horsecollar also sleeps nearby, his tail unrolling and rewinding on every snore like a child’s birthday party favor. In the village nearby, against a dramatic night sky, we see the town’s central alarm bell, with a tall building visible in the background nearby, glowing with actual flame. As mentioned above, this film marks a refinement of the painting and/or exposure techniques used in “Empty Socks”, setting the non-outlined stark white fire against dark backgrounds, magnifying the effect of its brightness and contrast. Another mouse enters the scene, racing toward the bell in a nightshirt, and repeats nearly identically the bell-ringing opening from the “Alice” cartoon above. At the fire staion, the volunteers are quick to respond. A long-necked ostrich serves as fire pole, extending its head between floors so that smaller characters can slide down. On the floor below, another “Alice” gag is repeated, with self-propelled trousers running into the room, pausing beneath the ostrich pole to catch the fire fighters and put them presentably into uniform. A few new variations appear in the fighters’ descent down the pole. A dachshund is so long, it winds around the ostrich’s neck like a serpent, then corkscrews its way downward. A puppy dog comes along, and misjudges his leap, landing in the ostrich’s mouth instead of on his neck, and is almost swallowed. Horace Horsecollar is the only one not yet out of bed, and repeats nearly verbatim the Alice gag of leaping into a suspended harness, then landing on his four horseshoes simultaneously to compete his outfit. Horace leaps upon the ostrich, but his weight is so great that he squashes the ostrich’s torso on the way down, exposing an internal skeletal structure where the ostrich’s neck is directly attached to his hip axle and legs like a walking football goalpost (a gag Disney also lifted from a previous production, “Gallopin’ Gaucho”). As the ostrich departs to join the crew, a last straggler rises from bed – the company’s ladder, which runs on its spokes like feet, drops its lower end through the hole to the floor below, then bends to cause its upper half to climb down its lower half to the ground floor.

The Fire Fighters (Disney/Columbia, 6/20/30 – Burt Gillett, dir.) gives one a partial sense of deja vi, as it is quickly apparent that it is a reworking of many principal sequences of “Alice the Fire Fighter”. However, the capable direction of Burt Gillett proves that by this time, Disney has gotten his timing down, and the pacing of all gags is brisk and drama-evoking, also aided greatly by a lively musical underscore (was this still Carl Stalling?) heightening the action. With substantial improvement in use of darker dramatic greys and detailed backgrounds, we open on a night shot of the firehouse, then dissolve to its interior, where a large crew of characters of various species (each one in their own bed rather than doubling or tripling up for endless cycles of characters) snores away. There is a bit of cross-pollenation from Universal here, as the snoring animation almost matches precisely the work of Freleng and Ising in “Fiery Fireman”’s opening shot – something that shouldn’t have been in Disney’s stock footage. Fire Chief Mickey has a bed at the head of the line, and the mouse also snores away the evening, almost swallowing a spider dangling from a web above him on every inhale. Horace Horsecollar also sleeps nearby, his tail unrolling and rewinding on every snore like a child’s birthday party favor. In the village nearby, against a dramatic night sky, we see the town’s central alarm bell, with a tall building visible in the background nearby, glowing with actual flame. As mentioned above, this film marks a refinement of the painting and/or exposure techniques used in “Empty Socks”, setting the non-outlined stark white fire against dark backgrounds, magnifying the effect of its brightness and contrast. Another mouse enters the scene, racing toward the bell in a nightshirt, and repeats nearly identically the bell-ringing opening from the “Alice” cartoon above. At the fire staion, the volunteers are quick to respond. A long-necked ostrich serves as fire pole, extending its head between floors so that smaller characters can slide down. On the floor below, another “Alice” gag is repeated, with self-propelled trousers running into the room, pausing beneath the ostrich pole to catch the fire fighters and put them presentably into uniform. A few new variations appear in the fighters’ descent down the pole. A dachshund is so long, it winds around the ostrich’s neck like a serpent, then corkscrews its way downward. A puppy dog comes along, and misjudges his leap, landing in the ostrich’s mouth instead of on his neck, and is almost swallowed. Horace Horsecollar is the only one not yet out of bed, and repeats nearly verbatim the Alice gag of leaping into a suspended harness, then landing on his four horseshoes simultaneously to compete his outfit. Horace leaps upon the ostrich, but his weight is so great that he squashes the ostrich’s torso on the way down, exposing an internal skeletal structure where the ostrich’s neck is directly attached to his hip axle and legs like a walking football goalpost (a gag Disney also lifted from a previous production, “Gallopin’ Gaucho”). As the ostrich departs to join the crew, a last straggler rises from bed – the company’s ladder, which runs on its spokes like feet, drops its lower end through the hole to the floor below, then bends to cause its upper half to climb down its lower half to the ground floor.

The company races to the fire, with Mickey utilizing a black cat on the hood of the engine to serve as siren, twisting and stretching the cat’s tail to produce ear-piercing yowls. (This was a gag which would be ripped off by Ub Iwerks within a few short months, providing a police siren for Flip the Frog’s “The Cuckoo Murder Case”.) The structure on fire is so weakened by the internal blaze, it bends precariously with every shift of the weight of its occupants, as they race to jump from windows on one side of the building or the other. Mickey’s ostrich stumbles en route while bringing up the rear end of the fire ladder, dragging most of the crew off the engine. One cat grabs at one of the fire hoses to cling onto, but yanks the boiler off the engine in the process. By the time Mickey and Horace reach the fire, they are driving only a chariot carrying a single hose and pail, and alone to fight the inferno. Mickey hooks up the hose to a hydrant, and waits for the jet of water – which never comes. Returning to the hydrant, he detaches the hose to find the trouble, and discovers water pressure is at a mere trickle. Bending the top of the hydrant over like a “U”, Mickey places his pail underneath, and milks the hydrant like a cow. He races for one of the fiery windows with the pail, but sloshes so much water out in the process, three drops are left to splash on the flames. Filling another pail, Mickey averts losing the water again by grabbing the displaced fluid from mid-air like a glob, and tossing it back into the bucket. But, rearing back to toss it in the flame, Mickey turns the bucket upside down, losing its contents again before the toss is made. Horace has better luck, running to a small pond, ingesting enough water to inflate like a balloon, then spitting his contents on the flames. Minnie appears in an upper story window, repeating the role of the female cat Julius rescued in the Alice comedy, likewise about to pass out from smoke inhalation. Mickey climbs up a fire escape of a neighboring building, and borrows the clothesline buoy gag from the elephant in the Alice film, in this case jumping into a pair of oversize trousers on the line to pull his way across to reach Minnie. But as he tugs at the clothesline in reverse to return the two of them to safe ground, the flame finds its way onto the rope, and severs it. The two mice fall, but the trousers turn upside down and billow out, providing a parachute so that they make a safe landing, for the traditional closing kiss.

An early entry in Max Fleischer’s new “Talkartoons” series, entitled Fire Bugs (Paramount, 5/9/31 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Ted Sears/Grim Natwick, anim), though far from a flawless cartoon, marks a forgotten milestone in animation history. A crew of fire-mice labor over keeping an engine in spit-and-polish condition, while a dog fireman and his horse sleep upstairs. (The gag is again repeated of the horse having his horseshoes off and waiting at the foot of the bed.) Without anyone actually sounding an alarm, the mice awaken the fireman and horse by tooting on a whistle on the engine’s boiler. The fireman and horse don their shoes, and leap for the fire pole. This fire house must be exceptionally tall, as a tracking shot shows the two sliding down past about nine stories of flooring, with the horse and fireman switching places in the lead as they continue to slide. They’ve picked up so much momentum when they reach ground level that they crash right through the floor, into a sub-basement where several barrels are kept in the manner of a winery, labeled “Fire Water.” The fireman gives the horse a drink of same from one of the taps, and the horse calls for more until the barrel is dry. Then the two leap back up the hole they have made, and its on to the fire.

An early entry in Max Fleischer’s new “Talkartoons” series, entitled Fire Bugs (Paramount, 5/9/31 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Ted Sears/Grim Natwick, anim), though far from a flawless cartoon, marks a forgotten milestone in animation history. A crew of fire-mice labor over keeping an engine in spit-and-polish condition, while a dog fireman and his horse sleep upstairs. (The gag is again repeated of the horse having his horseshoes off and waiting at the foot of the bed.) Without anyone actually sounding an alarm, the mice awaken the fireman and horse by tooting on a whistle on the engine’s boiler. The fireman and horse don their shoes, and leap for the fire pole. This fire house must be exceptionally tall, as a tracking shot shows the two sliding down past about nine stories of flooring, with the horse and fireman switching places in the lead as they continue to slide. They’ve picked up so much momentum when they reach ground level that they crash right through the floor, into a sub-basement where several barrels are kept in the manner of a winery, labeled “Fire Water.” The fireman gives the horse a drink of same from one of the taps, and the horse calls for more until the barrel is dry. Then the two leap back up the hole they have made, and its on to the fire.

The cartoon fills for time in its middle, unnecessarily having the horse stop in his tracks when he hears an organ grinder pumping out the notes of Mendelssohn’s Spring Song, to which the horse performs an effeminate ballet. Suddenly, the fireman spots a tower engulfed in smoke, and discovers there really is a fire to be put out. Coaxing the horse back into hitch, the two arrive inside the building, locating an apartment from which they hear music. A longhair lion suts on a bench before a grand piano, obsessed with his own musical performance, oblivious to the fact that a circle of fire is surrounding him from the four corners of the room. A modern-day viewer will instantly react, “Where have I seen this before?” You have, but in other cartoons – for this appears to be the first time that the famous Franz Liszt 2nd Hungarian Rhapsody – the classical anthem of all animation – was used to underscore an action sequence. Not only the music, but the gag situation would become an oft-repeated model for the industry – providing not only origin for any mad maestro obsessed with completing his performance in the face of overwhelming adversity, but first use of living flames dividing into multiple beings to cavort within and outside a musical instrument. Memorable films that would follow in its footsteps, to be discussed in subsequent chapters of this series, include Disney’s Mickey’s Fire Brigade, and Walter Lantz’s Musical Moments From Chopin. The fireman and horse try desperately to alert the pianist of his plight, but he keeps shooing them away – even when the sound box of his piano becomes invaded by little flame men, and they begin dancing out the notes of the rhapsody on the keyboard. Another flame converts to the shape of a rotating drill, and spears the pianist in the rear end, causing him to jump out of frame momentarily. The horse takes the opportunity to intercept the pianist’s return to the keyboard, by swallowing all of the keys off the piano. The obsessed musician merely continues by turning the horse upside down, and pounding out more notes from within by pressing on the horse’s belly. As this method becomes frustrating, the pianist squeezes the horse like a tube of toothpaste, forcing the keyboard out of his mouth and back onto the instrument. The horse and fireman position themselves under the instrument, and carry it, pianist, flame, and all, to where they can toss it out the window. The fireman falls out too, and everything hits the street – in groups. The pianist and main frame of the piano are first to land, the pianist still making motions with his hands as if he believes he is still playing. Batches of piano keys fall at intervals to provide the last well-known notes of the rhapsody, the last three accompanied by the landing of the fireman, sprawled across the keyboard with eyeballs twirling, out like a light. The pianist stands and addresses the theater audience. “My mother thanks you. My father thanks you> And I thank you. Good Bye.” And we iris out, on a film the industry would not soon forget, even if audiences ultimately did.

The cartoon fills for time in its middle, unnecessarily having the horse stop in his tracks when he hears an organ grinder pumping out the notes of Mendelssohn’s Spring Song, to which the horse performs an effeminate ballet. Suddenly, the fireman spots a tower engulfed in smoke, and discovers there really is a fire to be put out. Coaxing the horse back into hitch, the two arrive inside the building, locating an apartment from which they hear music. A longhair lion suts on a bench before a grand piano, obsessed with his own musical performance, oblivious to the fact that a circle of fire is surrounding him from the four corners of the room. A modern-day viewer will instantly react, “Where have I seen this before?” You have, but in other cartoons – for this appears to be the first time that the famous Franz Liszt 2nd Hungarian Rhapsody – the classical anthem of all animation – was used to underscore an action sequence. Not only the music, but the gag situation would become an oft-repeated model for the industry – providing not only origin for any mad maestro obsessed with completing his performance in the face of overwhelming adversity, but first use of living flames dividing into multiple beings to cavort within and outside a musical instrument. Memorable films that would follow in its footsteps, to be discussed in subsequent chapters of this series, include Disney’s Mickey’s Fire Brigade, and Walter Lantz’s Musical Moments From Chopin. The fireman and horse try desperately to alert the pianist of his plight, but he keeps shooing them away – even when the sound box of his piano becomes invaded by little flame men, and they begin dancing out the notes of the rhapsody on the keyboard. Another flame converts to the shape of a rotating drill, and spears the pianist in the rear end, causing him to jump out of frame momentarily. The horse takes the opportunity to intercept the pianist’s return to the keyboard, by swallowing all of the keys off the piano. The obsessed musician merely continues by turning the horse upside down, and pounding out more notes from within by pressing on the horse’s belly. As this method becomes frustrating, the pianist squeezes the horse like a tube of toothpaste, forcing the keyboard out of his mouth and back onto the instrument. The horse and fireman position themselves under the instrument, and carry it, pianist, flame, and all, to where they can toss it out the window. The fireman falls out too, and everything hits the street – in groups. The pianist and main frame of the piano are first to land, the pianist still making motions with his hands as if he believes he is still playing. Batches of piano keys fall at intervals to provide the last well-known notes of the rhapsody, the last three accompanied by the landing of the fireman, sprawled across the keyboard with eyeballs twirling, out like a light. The pianist stands and addresses the theater audience. “My mother thanks you. My father thanks you> And I thank you. Good Bye.” And we iris out, on a film the industry would not soon forget, even if audiences ultimately did.

Another mystery, remaining to be solved from the unmined holdings of the Terrytoons’ library at UCLA Film Archives, is Paul Terry’s The Fireman’s Bride (Audio-Cinema(?)/ Educational, 5/3/31), never included in the CBS television package, this leaving no information known as to its content. An honorable mention also goes to Terry for a film produced about a year earlier, Hawaiian Pineapple (5/18/30), which has been written-up in this column multiple times, including during our last set of travels dealing with aviation. A mouse pilot crashes into the side of a volcanic peak, penetrating the mountainside, and emerging immersed in flames upon his back. As he lies prone on the beach, with the flames engulfing him to the point he must certainly be barbecued, an aquatic fire brigade, mounted on fish equipped with siren and bells, respond to the scene, but only one, piloted by a hula maiden mouse, arrives to make the rescue, by spouting water from her fish’s mouth The pilot is miraculously cured instantly, and sails arm in arm with the hula maiden on her fish into the sunset.

Hot for more action? Tune in next week!

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

What a coincidence — just the other day I was watching an old cartoon on this very subject, and it occurred to me what a fine subject it would make for an Animation Trail! This is going to be a fun one. Burn, baby, burn!

I don’t think there’s any mystery about the appeal of the firefighting profession to small boys. It’s all about driving a big truck, blaring a siren, sliding down a pole, and squirting a hose indoors. The prospect of retiring on a pension at age 40 probably doesn’t even occur to them.

The music for “The Fire Fighters” was composed by Elbert “Bert” Lewis, who, like Carl Stalling, was a former silent film organist from Missouri (Stalling was from Lexington, Lewis from St. Louis). He scored all of the Silly Symphonies and Mickey Mouse cartoons produced in 1930 and a fair portion of them through 1935. Born in 1879, he was 50 when Disney hired him and probably the studio’s oldest employee. His scores show a reliance on familiar classical standards; most of the music in “The Fire Fighters”, for example, comes directly from Schubert’s “Der Erlkoenig” and Suppe’s “Jolly Robbers” Overture. Disney hired Frank Churchill in 1931, Leigh Harline in 1933, and Albert Hay Molette in 1935, and by then they were doing most of the heavy lifting for the studio’s music department. Lewis later scored some short subjects for MGM but seems to have retired from the film industry around 1940. For more on Bert Lewis, please see MUSIC IN DISNEY’S ANIMATED FEATURES (2017) by James Bohn.

Funny how Tex Avery changed all our expectations by breaking the fourth wall. When the silhouette of the man standing up during the Krazy Kat video blocked the screen, I expected Krazy to turn around and fire his musket at him!

A higher res version of Alice The Fire Fighter:

https://youtu.be/3JnJT9VOg8A

Thanks Craig. I have replaced the embed we had with the better one you found in the post above.

Charles, for next time, consider checking out the earlier Mutt and Jeff short FIREMAN SAVE MY CHILD (1919), which Tommy Stathes and I restored for our first Cartoon Roots volume some years ago:

https://www.amazon.com/Cartoon-Roots-Blu-ray-DVD-Combo/dp/B00O5TOD0K/

I have always wondered just HOW many “fire” toons there are (and there are beaucoup). I will enjoy these to the max….TY!!

In addition to Mutt and Jeff’s “Fireman Save My Child” of 1919 (which is quite a funny cartoon, with lively animation by Dick Huemer), another short with the same title was released in 1921 as part of the Tony Sarg’s Almanac series. The Library of Congress has a print; unfortunately, it’s almost completely deteriorated, and is kept mainly as an example of how film breaks down after a hundred years. Apparently it was made using animated marionettes in silhouette.

In “S’Matter Pete” (Bray Studios, Hot Dog Pictures, 15/3/27 — Walter Lantz, dir.), a live-action Walter Lantz is trying to light a gas stove as Pete the Pup and a number of other cartoon animals look on. When the stove explodes and catches fire, Pete jumps into a picture of a waterfall on the wall and redirects the flow of the water onto the stove. He thus manages to put out the fire, but in so doing winds up flooding the whole room.

Will the Kinex stop-motion short “The Fire Brigade” (1928) be included in the upcoming Stop Motion Marvels collection? Order it and find out!

I hope to see “Honeymoon Hotel” covered in an upcoming installment of this series. It was the first color cartoon from the Warner studio, it was released on my birthday in 1934, and it contains lots of pre-code gags and a romance so hot that it causes a fire.

Fire Bugs was released in 1930, not 1931. It’s one of the very first Fleischer cartoons (if not the first) with animation by Grim Natwick.

Can anyone help, I remember only one scene when lava burns the house roof and turns it into popcorns. There were some children also. Can anyone name that cartoon, does anyone know what cartoon it is?