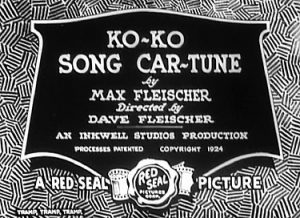

Max Fleischer had a pioneer’s interest in the burgeoning technology of adding sound to motion pictures. This explains his connections with Lee DeForest, who had been working his “phonofilms” system for years, wirh no great financial returns. DeForest was a pioneer in the field of radio, but his phonofilms were far from a commercial success, Fleischer produced several of his “Song Car-tunes”, with DeForest soundtracks, which were released through a joint venture called Red Seal Pictures. The experiment ended at the end of 1926, with the Song Car-Tunes abadoned for the 1927 and 1928 release years, and all Inkwell films remaining silent.

Max Fleischer had a pioneer’s interest in the burgeoning technology of adding sound to motion pictures. This explains his connections with Lee DeForest, who had been working his “phonofilms” system for years, wirh no great financial returns. DeForest was a pioneer in the field of radio, but his phonofilms were far from a commercial success, Fleischer produced several of his “Song Car-tunes”, with DeForest soundtracks, which were released through a joint venture called Red Seal Pictures. The experiment ended at the end of 1926, with the Song Car-Tunes abadoned for the 1927 and 1928 release years, and all Inkwell films remaining silent.

Paramount Pictures realized that sound was here to stay by the Summer of 1928. Instead of buying up existing music publishers as Warner Bros. had done, they set up their own tin pan alley publishing firm, Famous Music. This firm drew its name from one of the earlier names of the film company, Famous Players. This also explains why, when they later took over Max Fleischer’s business in the 1940’s they rechristened the animation department Famous Studios. By the end of 1929, Paramount had put out a seemingly endless stream of musicals – operettas, campus comedies, backstage musicals, and personality-driven pictures. It seemed like every third song that year put on records was a “talkie musical hit” from the silver screen. Amidst this atmosphere, Fleischer would eventually return to the medium of sound, resuming the musical sing-alongs as “Screen Songs”, and also adding music and voices to his new series of one-shot episodes, under the series banner “Talkartoons”.

Unique to the experience of the Song Car-Tunes and eventually the Screen Songs was the “bouncing ball” which would lead the audiences in the rhythm of the subject song and highlight the words to be sung, as opposed to static slides more typical to the likes of magic lantern shows. Dave Fleischer is reputed to have been the man literally behind the scenes, with a luminescent ping pong ball on a stick to wave over the song lyrics, whether on a static slide or eventually on a rolling drum. The amazing part about this is the unique talent it must have taken to coordinate the ball from a vantage point behind the lyric projection, in which the song lyric would be seen backwards (right to left). It was uncanny that Dave was able to figure out what words to bounce over while viewing each lyric sheet as a mirror image in a blackened room (presuming this was in fact the way the effect was achieved)..

Many of the early films in the series are lost to time, having presumably deteriorated to powder and jelly long ago. We will thus discuss what is known of the title songs from these early episodes. Where known, indications below will note whether films were released silent, or with a DeForest soundtrack.

Many of the early films in the series are lost to time, having presumably deteriorated to powder and jelly long ago. We will thus discuss what is known of the title songs from these early episodes. Where known, indications below will note whether films were released silent, or with a DeForest soundtrack.

Daisy Bell (May, 1924, silent), a song perhaps better known as “A Bicycle Built For Two”, popular both in the U.S. and the U.K. When the song came out, the recording industry was in its infancy, so we don’t know of any 1892 versions of the song. In the 1930’s, British music hall comedienne Florrie Forde recoded it for Zonophone’s “The Twin” label, then electrically for British Rex and Columbia. The song would become an olde tyme standard, receiving revival by Dinah Shore on Bluebird, Gerald Adams and the Variety Singers on Regal, the Orchestra Mascotte on Odeon, the McNulty Family (an Irish family, who eventually spawned Dennis Day as Eugene McNulty) on Decca, the Brittanica Accordion Band on Decca, the Old-Time Singers on HMV, Frank Quinn (a singer and multi-instrumentalist) and Nan Fitzpatrick on Columbia, and in Medleys by Jack Hylton on HMV, Reginald Foort on HMV, Winifred Atwell on Phillips, and in several re-recordings as part of “Old Timers Night at the Pops” by the Boston Pops on RCA/Victor. More recently, it is well remembered as an old chestnut by Alvin and the Chipmunks on Liberty – and sung by Hal 9000 in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Dixie (June, 1924, silent) – The perennial from the Civil War, the progenitor of many songs that treated anything South of the Mason-Dixon line as heaven on earth, a trope that would continue in cartoons as late as 1953, with Bugs Bunny’s Fresh Hare (1942) and Southern Fried Rabbit (1953). Mabel Garrison provided an early recording it on Victor Red Seal. Dinah Shore again revived it much later, this time on Columbia. And Bing Crosby would perform it in film, in a bio-feature of the same name (1943), as the composer, allegedly turning a slow ballad into a lively hit by picking up the tempo to cover over a fire erupting in the theatre backstage. Curiously, no commercial recording by him was issued. The trailer below is clearly politically incorrect – you’ve been warned.

Goodbye, My Lady Love (June, 1924, sound), a hit for Joe Howard, who also composed Michigan J. Frog’s theme song, “Hello, Ma Baby”. Long after the initial success, Joe would get to record the two pieces together electrically for Vocalion in 1936. Harry MacDonough recorded the piece on Victor during its heyday. Russ Morgan revived the number in the 30’s for Decca. One of its last appearances was part of a medley on an album from Epic dedicated to the memory of the minstrel show, “Gentlemen, Be Seated”.

Mother, Mother, Mother, Pin a Rose on Me (June, 1924, sound). Recorded by Billy Murray on Victor. Later revived in the late 1940’s by Kitty Kallen on Mercury.

Come Take a Trip in My Airship (June, 1924, sound). Recorded by J.W. Myers for Columbia in 1904, and in the same year by Billy Murray on Victor’s Monarch label.

Oh, Mabel.(silent) (Filmographies claim to credit the film to May, 1924, but may likely be placing it too early, as all the commercial recording activity on the piece seems to commence between November of 1924 and January of 1925. California Ramblers’ groups recorded it for four different labels – Columbia (with full band), Edison (full band), Cameo (full band), and Okeh (a small contingent of the group, known as “The Goofus Five”). The Oriole Orchestra (directed by Dan Russo and Ted Fio Rito, the latter of whom was one of the composers of the song) recorded it for Brinswick. Victor covered it with Waring’s Pennsylvanians, and also a vocal record by Billy Murray. Columbia gave it to Billy Jones and Ernest Hare. In England, Arthur Raymond recorded it for Regal. It was also widely covered in plain generic dance versions by many smaller record companies too numerous to mention.

Old Pal (June, 1925, silent). Without a film for guidance, it is difficult to say precisely which of multiple possible songs with similar titles this cartoon was featuring. Knowing Fleischer’s pattern of generally not featuring current pop songs in the first blush of popularity (“Oh Mabel” being an exception), and preferring to use songs with some established staying power, I believe it may have featured a 1921 song. “Old Pal, Why Don’t You Answer Me”, recorded by Henry Burr on Victor ad Columbia (the latter on the flip side of Al Jolson’s “Avalon”), and Paramount/Puritan. The Original Dixieland Jazz Band included it in a medley around 1920 for Victor, though I’ve not as yet verified the title assigned to the medley. George Beaver (probably Irving Kaufman) recorded it on 7” Melodisc for Emerson. A salon orchestra headed by Herbert Soman recorded it for Edison Diamond Disc. Harry Vernon recorded it for British Regal.

The Shiek of Araby (June, 1925, silent). Recorded by the Club Royal Orchestra, (conducted by saxophone virtuoso Clyde Doerr, who had come out of Art Hickman’s orchestra) on Victor, Ray Miller on Columbia, the California Ramblers for Vocalion, and Nathan Glantz on Okeh. Numerous other smaller labels would pick up the piece. As the song became a standard, revivals would occur by Red Nichols on Brunswick (with brief vocal by Treg Brown of Warner cartoon fame, interrupted by Jack Teagarden), Duke Ellington on Brunswick, Spike Jones on Bluebird, the Firehouse Five Plus Two on Good Time Jazz, and Lou Monte in 1958 for RCA Victor, among numerous others.

Next Time: more from the not-so-silent era.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

Oh, I was hoping you’d do the songs of the Fleischer cartoons! This is going to be a great series.

Another notable cover of “The Sheik of Araby” was by the Beatles, in their unsuccessful audition for Decca in 1962, with George singing lead and Pete Best on Drums.

Dinah Shore was a looker.

Just sayin’…

Right you are! Considering she had some success in the movies, and especially on tv, it’s surprising she lost her first job as a band singer because the leader thought she wasn’t attractive enough!

An 1894 recording of “Daisy Bell” can be found here:

http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder10477

Well, I’m glad you’re doing this with the Fleischer cartoons – at long last!

I’ve always been curious about a piece of music that was used for CAN YOU TAKE IT (1934) where Popeye goes through a series of torture devices to see if he’s “man enough” to join the “Bruiser Boy’s Club.” I can’t tell if the music is something that Sammy Timberg composed or if it was from music in the Famous music catalogue or from a popular song. Anybody know?

Leonard – The tune used in that sequence is “The Bulldog Song” or “The Bulldog on the Bank, the Bull Frog in the Pool” ttp://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder3751 and other variations of the title. It goes back to at least the late 19th century.

Thank you, Rich! It had the feel of a one-time popular tune to me and not necessarily something Sammy T. composed for it. Thanks again!

Thanks for sorting out the tangled history of the early deForrst Song Car-tunes. Some may recall that I issued a DVD of them a number of years ago when I acquired the negatives to a handful of them. A couple of points need clarification here, however. As I mention in my book, the Song Car-Tunes continued into early 1927, one of the last being BY THE LIGHT OF THE SILVERY MOON. The continuation of these sound releases was caused by the bankruptcy of The Red Seal Pictures, Corporation. This came just five months before the monumental release of THE JAZZ SINGER, which as we know ushered in the sound era.

The Fleischers were paired with Paramount by Alfred Weiss following the dissolution of Red Seal that same year. They resurrected OUT OF THE INKWELL as THE INKWELL IMPS for Paramount release as silent cartoons up to 1929. Max and Dave left Weiss and Max managed to secure a new contract with Paramount in 1928 which resulted in a return to the song films as SCREEN SONGS, which started playing on Broadway in the fall of 1928, but did not see formal release until February 1929 when Paramount’s theaters started having sound equipment installed across the country.

Lastly, that is Lou Fleischer, Head of the Music Department who is bouncing the ball in the picture. Dave did not do this.