We’ll wrap up today theatrical fire animation up through 1980, then focus our attentions next week on television. Included this week are clips from three features, a Disney educational special featuring Walt himself, a neat Tom and Jerry romp, and some late Terry and Paramount installments that quickly crossed the gap from big to small screen distribution. Fire away!

Big Chief No Treaty (Terrytoons/Fox, Deputy Dawg, 8/1/62 – Bob Kuwahara, dir.) – Muskie and Vincent Van Gopher encounter a new rival – a huge Indian chief, who steals watermelons and eggs from them as fast as they themselves can steal them from the watermelon patch and the henhouse. They alert (is that the proper adjective for him in any condition?) Deputy Dawg, who promises to give that boy “30 days in the pokey”. Deputy encounters the chief lawbreaking again, using a “No Fishing” sign as a fishing pole at the creek, and engages the chief in a battle of fisticuffs, finally bringing the chief in in handcuffs (after Deputy endures a black eye or two). The Sheriff is in when he arrives at the jail house, and is aghast at the identity of the prisoner. “That’s Big Chief No Treaty. Turn him loose!” The puzzled Deputy unlocks the chief’s cuffs, and receives a tweak on the nose by the chief for his troubles as the Indian departs. The Sheriff explains that the chief never signed a peace treaty with the United States, so that no one has jurisdiction over him. The Sheriff warns Deputy that if the chief is molested again, he might sue the County for as much as fifteen or twenty dollars! Overhearing that the chief is off limits, Muskie and Vince hatch a scheme to disguise themselves in an oversized suit (standing one atop the other), which they hope will fool Deputy at a distance into thinking that they’re the chief, allowing them open season to break whatever laws they will.

Big Chief No Treaty (Terrytoons/Fox, Deputy Dawg, 8/1/62 – Bob Kuwahara, dir.) – Muskie and Vincent Van Gopher encounter a new rival – a huge Indian chief, who steals watermelons and eggs from them as fast as they themselves can steal them from the watermelon patch and the henhouse. They alert (is that the proper adjective for him in any condition?) Deputy Dawg, who promises to give that boy “30 days in the pokey”. Deputy encounters the chief lawbreaking again, using a “No Fishing” sign as a fishing pole at the creek, and engages the chief in a battle of fisticuffs, finally bringing the chief in in handcuffs (after Deputy endures a black eye or two). The Sheriff is in when he arrives at the jail house, and is aghast at the identity of the prisoner. “That’s Big Chief No Treaty. Turn him loose!” The puzzled Deputy unlocks the chief’s cuffs, and receives a tweak on the nose by the chief for his troubles as the Indian departs. The Sheriff explains that the chief never signed a peace treaty with the United States, so that no one has jurisdiction over him. The Sheriff warns Deputy that if the chief is molested again, he might sue the County for as much as fifteen or twenty dollars! Overhearing that the chief is off limits, Muskie and Vince hatch a scheme to disguise themselves in an oversized suit (standing one atop the other), which they hope will fool Deputy at a distance into thinking that they’re the chief, allowing them open season to break whatever laws they will.

The plot doesn’t work, as Deputy looks through a spyglass, revealing a close-up image of Muskie’s war-painted face. Deputy races to the scene of Muskie’s latest raid on the henhouse, but misses seeing the real chief again steal away Muskie’s haul of eggs – resulting in the Deputy tackling the chief again, and the chief declaring war on “paleface lawman”. Deputy retreats to the jailhouse amidst a hail of arrows. Once he is locked inside, the arrows begin flying in the windows, until one of them lands in a wall with an added element of danger attached – flame. The chief has taken a new position atop a high cliff, where he has started a campfire with which to light the tip of his arrows. Deputy races outside for buckets of water, alternating between dodging the Indian’s shots and trying to put out the flames in the log cabin walls of the jail house. The chief maintains the upper hand until the wind shifts, setting the grass around the cliff into a blazing brushfire. Surrounded, the chief calls desperately for help. Deputy forgets their adversary toles, and races to the rescue with a tall ladder, scaling it to guide the chief to safety. In recognition of the Deputy’s bravery, the chief declares an end to the war, and to his lawbreaking, signs a peace treaty, and even presents Deputy with an honorary chief’s headdress. “I feel like a cotton pickin’ turkey”, smiles Deputy. But when the chief attempts to bestow a final honor upon Deputy – making him a “blood brother” while holding a large knife – our heroic Deputy faints dead away, with Muskie commenting, “Now how do you like that?”

The plot doesn’t work, as Deputy looks through a spyglass, revealing a close-up image of Muskie’s war-painted face. Deputy races to the scene of Muskie’s latest raid on the henhouse, but misses seeing the real chief again steal away Muskie’s haul of eggs – resulting in the Deputy tackling the chief again, and the chief declaring war on “paleface lawman”. Deputy retreats to the jailhouse amidst a hail of arrows. Once he is locked inside, the arrows begin flying in the windows, until one of them lands in a wall with an added element of danger attached – flame. The chief has taken a new position atop a high cliff, where he has started a campfire with which to light the tip of his arrows. Deputy races outside for buckets of water, alternating between dodging the Indian’s shots and trying to put out the flames in the log cabin walls of the jail house. The chief maintains the upper hand until the wind shifts, setting the grass around the cliff into a blazing brushfire. Surrounded, the chief calls desperately for help. Deputy forgets their adversary toles, and races to the rescue with a tall ladder, scaling it to guide the chief to safety. In recognition of the Deputy’s bravery, the chief declares an end to the war, and to his lawbreaking, signs a peace treaty, and even presents Deputy with an honorary chief’s headdress. “I feel like a cotton pickin’ turkey”, smiles Deputy. But when the chief attempts to bestow a final honor upon Deputy – making him a “blood brother” while holding a large knife – our heroic Deputy faints dead away, with Muskie commenting, “Now how do you like that?”

Snuffy’s Song (Paramount, Comic Kings (Snuffy Smith and Barney Google), 6/1/62 – Seymour Kneitel. dir.) – Paramount had just signed on to produce a new run of shorts for television featuring a trio of characters from the pages of King Features Syndicate’s Sunday comics section – Beetle Bailey, Snuffy Smith, and Krazy Kat. They would take responsibility for about half the Beetle Baileys, and for all the Snuffy Smiths (save a failed pilot by Jack Kinney), while only selling two pilot episodes for the Krazy Kat series. To promote the new venture, Paramount also secured rights from King Features (who held the copyrights) to screen several of these productions theatrically, filling gaps to meet their contractual theatrical distribution quota, under the series banner “Comic Kings”. As production budgets had already dwindled to bare-bones level for what was being issued in the normal theatrical output, these shorts, despite somewhat limited animation, did not make a bad fit, and in some instances may actually have appeared of superior quality to many of the one-shots customarily released to theaters. I remember seeing one of the Beetle Baileys, “Hero’s Reward”, in this format a year or so after its premiere, as part of my first kiddie matinee with the heavily-promoted European all-animal film, “The Secret of Magic Island”. It took me about 40 years to see it again through home video, but I carried with me memories of seeing it on the big screen, and instantly recognized it in the collection, color values and all. So one can’t say that these releases didn’t leave some lasting impression.

Snuffy’s Song (Paramount, Comic Kings (Snuffy Smith and Barney Google), 6/1/62 – Seymour Kneitel. dir.) – Paramount had just signed on to produce a new run of shorts for television featuring a trio of characters from the pages of King Features Syndicate’s Sunday comics section – Beetle Bailey, Snuffy Smith, and Krazy Kat. They would take responsibility for about half the Beetle Baileys, and for all the Snuffy Smiths (save a failed pilot by Jack Kinney), while only selling two pilot episodes for the Krazy Kat series. To promote the new venture, Paramount also secured rights from King Features (who held the copyrights) to screen several of these productions theatrically, filling gaps to meet their contractual theatrical distribution quota, under the series banner “Comic Kings”. As production budgets had already dwindled to bare-bones level for what was being issued in the normal theatrical output, these shorts, despite somewhat limited animation, did not make a bad fit, and in some instances may actually have appeared of superior quality to many of the one-shots customarily released to theaters. I remember seeing one of the Beetle Baileys, “Hero’s Reward”, in this format a year or so after its premiere, as part of my first kiddie matinee with the heavily-promoted European all-animal film, “The Secret of Magic Island”. It took me about 40 years to see it again through home video, but I carried with me memories of seeing it on the big screen, and instantly recognized it in the collection, color values and all. So one can’t say that these releases didn’t leave some lasting impression.

Snuffy’s Song was the debut episode of the Snuffy series, part of a three-episode trilogy of extended-length shorts covering adventures of Snuffy in the big city (a venue not generally revisited again in the rank-and-file episodes of the series that followed). The others of the trilogy included “The Method and Maw” and “The Hat”, in that order (though theatrical schedules appear to have reversed the intended order of the second and third titles). As our story opens, Barney Google (Snuffy’s dude cousin, who is always looking for a quick money-making scheme) reads in the papers about a local boy made good – a hog caller, who, when given a guitar to accompany his calling, scores his first million dollars in a recording contract. Why, thinks Barney, can’t I make a discovery like that? His prayers are quickly answered, as the bellowing notes of Snuffy Smith are heard from outside, in an original tune used as the series’ theme, “Great Balls o’ Fire” (no relation to the rock standard by Jerry Lee Lewis, to whom no royalty was necessary, as Snuffy had for many long years been using the expression before Lewis’s song was ever composed). It is not only, however, Snuffy’s notes that attract Barney’s ears, as Snuffy also has a “gimmick” to go with it. Being the laziest hillbilly in the hills, Snuffy is above performing manual labor to do his chores, so has invented a steam-powered automatic wood-chopper to do the task for him, while he himself lounges peacefully under a tree. The invention is powered by a fire under an oil drum that serves as a boiler, periodically releasing steam to propel an axe onto a chopping block. It provides a percussive sound background for what Snuffy refers to as his “work song”, and Barney envisions Snuffy and his machine as a substantial pile of dollar bills. Quickly, he fast-talks Snuffy into a trip to the big city to obtain a recording contract. When Barney mentions the potential of a million dollars, Snuffy responds, “Is that mote than a dollar thirty?” Seems Snuffy’s had his eye on spending such amount on a new plow, because it tires him out watching his wife Lowezy struggle to pull the old one. Barney promises Snuffy will get his $1.30 – and Barney will just take “whatever change is left over.” “You’re a good man, Google”, responds Snuffy, with a handshake to seal the deal.

Snuffy’s Song was the debut episode of the Snuffy series, part of a three-episode trilogy of extended-length shorts covering adventures of Snuffy in the big city (a venue not generally revisited again in the rank-and-file episodes of the series that followed). The others of the trilogy included “The Method and Maw” and “The Hat”, in that order (though theatrical schedules appear to have reversed the intended order of the second and third titles). As our story opens, Barney Google (Snuffy’s dude cousin, who is always looking for a quick money-making scheme) reads in the papers about a local boy made good – a hog caller, who, when given a guitar to accompany his calling, scores his first million dollars in a recording contract. Why, thinks Barney, can’t I make a discovery like that? His prayers are quickly answered, as the bellowing notes of Snuffy Smith are heard from outside, in an original tune used as the series’ theme, “Great Balls o’ Fire” (no relation to the rock standard by Jerry Lee Lewis, to whom no royalty was necessary, as Snuffy had for many long years been using the expression before Lewis’s song was ever composed). It is not only, however, Snuffy’s notes that attract Barney’s ears, as Snuffy also has a “gimmick” to go with it. Being the laziest hillbilly in the hills, Snuffy is above performing manual labor to do his chores, so has invented a steam-powered automatic wood-chopper to do the task for him, while he himself lounges peacefully under a tree. The invention is powered by a fire under an oil drum that serves as a boiler, periodically releasing steam to propel an axe onto a chopping block. It provides a percussive sound background for what Snuffy refers to as his “work song”, and Barney envisions Snuffy and his machine as a substantial pile of dollar bills. Quickly, he fast-talks Snuffy into a trip to the big city to obtain a recording contract. When Barney mentions the potential of a million dollars, Snuffy responds, “Is that mote than a dollar thirty?” Seems Snuffy’s had his eye on spending such amount on a new plow, because it tires him out watching his wife Lowezy struggle to pull the old one. Barney promises Snuffy will get his $1.30 – and Barney will just take “whatever change is left over.” “You’re a good man, Google”, responds Snuffy, with a handshake to seal the deal.

Barney “arranges” transportation for the family – sitting on the rear bumper and fenders of a bus headed to the big city. He alibis to Snuffy why they’re not sitting inside, telling him that “Those are the cheap seats”, while their place to sit is “air-conditioned”. They finally arrive at what is obviously intended to be Hollywood, staring in awe at the headquarters of the Seymour Stereo Recording Company – a cylindrical tower which rotates on a center spindle, the roof of which appears to be a giant record revolving with phonograph tone arm atop. (This gag is a clear parody of the landmark Capitol Records Tower, still standing in Hollywood, which many felt was built to resemble a stack of records.) With a little effort to get the right timing, Lowezy jumps onto the doorstep of the building as it rotates by, catching up Barney and Snuffy on the next revolutions, and they, together with Snuffy’s invention strapped to Lowezy’s back, take a speed elevator to the tower’s top floor, entering the palatial office of Seymour Stereo. Seymour is busy on the phone wheeling and dealing in search of a “new sound”, and quickly orders the hillbilly trio out of his office, referring to them as something for “Halloween”. Lowezy observes he is not very hospitable, and Snuffy proclaims he can calm him down a mite. “I won’t stand for publicity stunts”, rants Seymour, until Snuffy points his rifle in Seymour’s face. “Now just sit. No standin’”, states Snuffy. Barney begins his sales pitch to Seymour, while Lowezy sets up the “orchestry” – Snuffy’s wood chopper. To produce a fire, Lowezy begins breaking up into splinters a priceless Chippendale antique chair for “kindling”, placing it under the oil drum, and lights a match. The machine does its stuff, and Snuffy gives out with the chorus of his song. To Barney’s delight, Seymour is impressed. “We’re going to bust the record business wide open”, he declares, handing Snuffy a contract. Sniffy is instructed ti sign his first and last name, which he does by drawing a pair of “X”s on the paper. Everyone is so busy in celebrating, they fail to notice that Lowezy’s bonfire has spread to the suite’s rug, and further jumped to curtains on the wall, filling the room with flames and clouds of soot. Seymour announces they’ll set up a recording session for the morning, and produce a whole album, for which Barney suggests the title, “The Sweetest Roll This Side of the Rockies”. As the entire room fills with billowing black clouds, the group remain euphoric and oblivious to the situation, while Seymour continues, “This is going to be the hottest record we’ve ever made, Yes sir, you just watch our smoke!” We do exactly that, as the smoke clouds black out the scene, transitioning us to Act Three of ourr story.

Barney “arranges” transportation for the family – sitting on the rear bumper and fenders of a bus headed to the big city. He alibis to Snuffy why they’re not sitting inside, telling him that “Those are the cheap seats”, while their place to sit is “air-conditioned”. They finally arrive at what is obviously intended to be Hollywood, staring in awe at the headquarters of the Seymour Stereo Recording Company – a cylindrical tower which rotates on a center spindle, the roof of which appears to be a giant record revolving with phonograph tone arm atop. (This gag is a clear parody of the landmark Capitol Records Tower, still standing in Hollywood, which many felt was built to resemble a stack of records.) With a little effort to get the right timing, Lowezy jumps onto the doorstep of the building as it rotates by, catching up Barney and Snuffy on the next revolutions, and they, together with Snuffy’s invention strapped to Lowezy’s back, take a speed elevator to the tower’s top floor, entering the palatial office of Seymour Stereo. Seymour is busy on the phone wheeling and dealing in search of a “new sound”, and quickly orders the hillbilly trio out of his office, referring to them as something for “Halloween”. Lowezy observes he is not very hospitable, and Snuffy proclaims he can calm him down a mite. “I won’t stand for publicity stunts”, rants Seymour, until Snuffy points his rifle in Seymour’s face. “Now just sit. No standin’”, states Snuffy. Barney begins his sales pitch to Seymour, while Lowezy sets up the “orchestry” – Snuffy’s wood chopper. To produce a fire, Lowezy begins breaking up into splinters a priceless Chippendale antique chair for “kindling”, placing it under the oil drum, and lights a match. The machine does its stuff, and Snuffy gives out with the chorus of his song. To Barney’s delight, Seymour is impressed. “We’re going to bust the record business wide open”, he declares, handing Snuffy a contract. Sniffy is instructed ti sign his first and last name, which he does by drawing a pair of “X”s on the paper. Everyone is so busy in celebrating, they fail to notice that Lowezy’s bonfire has spread to the suite’s rug, and further jumped to curtains on the wall, filling the room with flames and clouds of soot. Seymour announces they’ll set up a recording session for the morning, and produce a whole album, for which Barney suggests the title, “The Sweetest Roll This Side of the Rockies”. As the entire room fills with billowing black clouds, the group remain euphoric and oblivious to the situation, while Seymour continues, “This is going to be the hottest record we’ve ever made, Yes sir, you just watch our smoke!” We do exactly that, as the smoke clouds black out the scene, transitioning us to Act Three of ourr story.

Next day, the recording session commences. To ensure no repeat of the previous day’s disaster, Seymour has added something new to the studio’s equipment – a ring of gas burners installed in the floor, to provide the necessary heating to Snuffy’s oil drum. Snuffy’s singing begins, and some visiting executives of the company in the control booth shake Seymour’s hand and concur Snuffy is definitely their ticket to success. Barney’s eyes transform into dollar signs – until an unexpected development transforms the images in his eyes to the words, “No Sale”. The gas jets prove to be too much for the boiling oil drum, and it hisses and spouts steam uncontrollably, the timing of the axe whacks increasing frantically and going entirely out of timing with the music. Reaching the point of explosion, the drum suddenly blasts off like a rocket, straight through the turntable roof of the tower, and out into deep space. The “new sound” is gone, and Seymour blathers, “You’ve ruined me! Get out!” “Not till I get my dollar thirty!”, retorts Snuffy. “I said out – way out!” screams Seymour, pressing a button in the control booth marked “Instant Revenge”. Three robotic devices with claw hands roll into the studio, seize up the hillbilly three by the collar, and act as automatic bouncers to dump them outside the building onto the street. As they sit, bewildered and broke, they hear the call of a passing newsboy, carrying a late extra hot off the local press. “Oil drum in orbit. President congratulates Pentagon. Pentagon puzzled.” High overhead, they observe the rocket-powered drum in its pass. “There goes the sweetest music this side of heaven”, says Barney (lifting the slogan used for decades to describe the music of Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians). “Play pretty for the people”, adds Lowezy to the drum (borrowing another famous expression of bandleader Louis Prima), as the drum circles Earth repeatedly in space, for the fade out.

Next day, the recording session commences. To ensure no repeat of the previous day’s disaster, Seymour has added something new to the studio’s equipment – a ring of gas burners installed in the floor, to provide the necessary heating to Snuffy’s oil drum. Snuffy’s singing begins, and some visiting executives of the company in the control booth shake Seymour’s hand and concur Snuffy is definitely their ticket to success. Barney’s eyes transform into dollar signs – until an unexpected development transforms the images in his eyes to the words, “No Sale”. The gas jets prove to be too much for the boiling oil drum, and it hisses and spouts steam uncontrollably, the timing of the axe whacks increasing frantically and going entirely out of timing with the music. Reaching the point of explosion, the drum suddenly blasts off like a rocket, straight through the turntable roof of the tower, and out into deep space. The “new sound” is gone, and Seymour blathers, “You’ve ruined me! Get out!” “Not till I get my dollar thirty!”, retorts Snuffy. “I said out – way out!” screams Seymour, pressing a button in the control booth marked “Instant Revenge”. Three robotic devices with claw hands roll into the studio, seize up the hillbilly three by the collar, and act as automatic bouncers to dump them outside the building onto the street. As they sit, bewildered and broke, they hear the call of a passing newsboy, carrying a late extra hot off the local press. “Oil drum in orbit. President congratulates Pentagon. Pentagon puzzled.” High overhead, they observe the rocket-powered drum in its pass. “There goes the sweetest music this side of heaven”, says Barney (lifting the slogan used for decades to describe the music of Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians). “Play pretty for the people”, adds Lowezy to the drum (borrowing another famous expression of bandleader Louis Prima), as the drum circles Earth repeatedly in space, for the fade out.

I’m Just Wild About Jerry (Chuck Jones/MGM, 4/7/65 – Chuck Jones, dir.), is a fast-moving, visually inventive, non-stop chase in and out of a department store. It is a curious production for its inclusion of a high number of POV dimensional shots that either depict objets and scenics at angles of extreme perspective to vanishing point or have characters and objects “comin’ at ya” as if about to strike you in the face – leaving one to wonder, had the film been planned for some kind of a release in 3-D? For the amount of work put into such shots, you’d have thought so – but with what film of its day could it have been intended for release, 3-D being such a rarity in the 60’s? Nevertheless, it appears such a format never became a reality (more’s the pity. What would be the cost of computer-retrofitting the film for such a version, like “Beauty and the Beast?) A further interesting historical observance is that Jones had previously been assigned the only 3-D project produced by Warner Brothers cartoons, “Lumber Jack Rabbit”, in the 1950’s – and had made a near-disaster of it, with a scant few shots depicting any true layering or dimensionality, and most action depicted in basic side-to-side panning (with less look of depth than Bob Clampett had achieved from 2-D panning canyon backgrounds in “Wabbit Twouble”). Why couldn’t Jones have thought of shots and layouts on the lines of this T&J episode when he had the technology at his disposal in the 50’s to make them even more realistic?

I’m Just Wild About Jerry (Chuck Jones/MGM, 4/7/65 – Chuck Jones, dir.), is a fast-moving, visually inventive, non-stop chase in and out of a department store. It is a curious production for its inclusion of a high number of POV dimensional shots that either depict objets and scenics at angles of extreme perspective to vanishing point or have characters and objects “comin’ at ya” as if about to strike you in the face – leaving one to wonder, had the film been planned for some kind of a release in 3-D? For the amount of work put into such shots, you’d have thought so – but with what film of its day could it have been intended for release, 3-D being such a rarity in the 60’s? Nevertheless, it appears such a format never became a reality (more’s the pity. What would be the cost of computer-retrofitting the film for such a version, like “Beauty and the Beast?) A further interesting historical observance is that Jones had previously been assigned the only 3-D project produced by Warner Brothers cartoons, “Lumber Jack Rabbit”, in the 1950’s – and had made a near-disaster of it, with a scant few shots depicting any true layering or dimensionality, and most action depicted in basic side-to-side panning (with less look of depth than Bob Clampett had achieved from 2-D panning canyon backgrounds in “Wabbit Twouble”). Why couldn’t Jones have thought of shots and layouts on the lines of this T&J episode when he had the technology at his disposal in the 50’s to make them even more realistic?

The film opens with creative animated titles (which also probably would have looked great if rendered with 3-D depth), panning down the windows of the stairwell of a tall building, as T&J carry on their endless pursuit down what seems an equally endless succession of staircases. They do finally reach ground level, and continue the chase down the incline of a steep city sidewalk. Jerry spots a misplaced set of child’s roller skates on the pavement, and hops onto one, using it as a sort of belly-flop skateboard down the hill (one shot of course in perspective, jumping over the camera lens). The block turns a sharp corner, and Jerry rounds it with an equally sharp turn. However, once in a blind spot from Tom’s approach, Jerry stops cold, dismounts the skate, and pushes it back around the corner into Tom’s path. Tom’s foot lands squarely in it, and he rolls off the corner and into the street, down the remainder of the hill, and stops in the middle of an intersection with a main thoroughfare, containing trolley tracks. One side of Tom’s body is suddenly illuminated with light, as the clanging bell of an approaching trolley is heard. Having no time to otherwise react, Tom reaches into an invisible “pocket” and produces a blindfold, with which he covers his own eyes like a man facing a firing squad, to bravely await his impending doom. The trolley hits, flattening him. Jerry disappears into the mail slot on the front door of a department store. Tom rises from the tracks to resume the pursuit, only to hear another trolley-bell clang and be bathed in another beam of half-light, this time from behind him. Tom again reaches for the blindfold, but never gets it tied, before he is flattened again. His new shape after these blows makes it easy for him to enter the department store by the same route as Jerry, compacted into a rectangular shape neatly fitting through the mail slot. The only thing that doesn’t quite get through the slot is Tom’s tail, getting caught in the metal hinged door. Tom pops back to normal shape, and chases Jerry down a long aisle and around a marble column – then gets a look back at his tail, extending a mile all the way back to the door (another vanishing-point perspective shot). Like a rubber band stretched to its limit, Tom’s tail springs him back to where he started, the limp loops of his overextended tail sagging like leftover decorations from a birthday party around him. Tom gives an embarrassed grin to the camera, and scoops up his yards of tail to make a tippy-toe exit from the shot back into the store.

The film opens with creative animated titles (which also probably would have looked great if rendered with 3-D depth), panning down the windows of the stairwell of a tall building, as T&J carry on their endless pursuit down what seems an equally endless succession of staircases. They do finally reach ground level, and continue the chase down the incline of a steep city sidewalk. Jerry spots a misplaced set of child’s roller skates on the pavement, and hops onto one, using it as a sort of belly-flop skateboard down the hill (one shot of course in perspective, jumping over the camera lens). The block turns a sharp corner, and Jerry rounds it with an equally sharp turn. However, once in a blind spot from Tom’s approach, Jerry stops cold, dismounts the skate, and pushes it back around the corner into Tom’s path. Tom’s foot lands squarely in it, and he rolls off the corner and into the street, down the remainder of the hill, and stops in the middle of an intersection with a main thoroughfare, containing trolley tracks. One side of Tom’s body is suddenly illuminated with light, as the clanging bell of an approaching trolley is heard. Having no time to otherwise react, Tom reaches into an invisible “pocket” and produces a blindfold, with which he covers his own eyes like a man facing a firing squad, to bravely await his impending doom. The trolley hits, flattening him. Jerry disappears into the mail slot on the front door of a department store. Tom rises from the tracks to resume the pursuit, only to hear another trolley-bell clang and be bathed in another beam of half-light, this time from behind him. Tom again reaches for the blindfold, but never gets it tied, before he is flattened again. His new shape after these blows makes it easy for him to enter the department store by the same route as Jerry, compacted into a rectangular shape neatly fitting through the mail slot. The only thing that doesn’t quite get through the slot is Tom’s tail, getting caught in the metal hinged door. Tom pops back to normal shape, and chases Jerry down a long aisle and around a marble column – then gets a look back at his tail, extending a mile all the way back to the door (another vanishing-point perspective shot). Like a rubber band stretched to its limit, Tom’s tail springs him back to where he started, the limp loops of his overextended tail sagging like leftover decorations from a birthday party around him. Tom gives an embarrassed grin to the camera, and scoops up his yards of tail to make a tippy-toe exit from the shot back into the store.

Tom is next seen hiding behind a column, on the lookout for Jerry. He emerges, with his yards of tail coiled around his lower torso, as if wearing a newly-knit pair of gray trousers. Suddenly, his backside is bathed in that same headlight glow we’ve seen twice before. Indoors? Well, not exactly, as this time, the light is not from a trolley car, but from a toy fire engine that Jerry has acquired from the toy department. Tom has so little time to react that his fingertips barely touch the blindfold before he is clobbered again. Tom is flipped into the air, and like his predecessor Claude Cat in many a Jones epic with Frisky Puppy, clings upside down on the ceiling, his teeth chattering and fur frazzled. Jerry gives him a coy wave as he passes, but Tom’s eyes have something else in view, as he slides back to ground level via one of the marble columns. A display of the fire engines is set up in the toy department, prominently featuring a device Jerry didn’t make use of – a remote control for the vehicles. Tom selects one of the control boxes, and presses a button. Jerry’s engine immediately screeches to a stop, so fast it loses its ladder, front fenders, and other components. Another push, and the vehicle shifts into reverse, then stops cold again, throwing off its clanging bell. (This throwing off of accessories is an interesting way to make the job simpler for the animators in the action that follows, reducing the engine to bare bones to save on line detail – a technique once previously used by Alex Lovy in Woody Woodpecker’s “Ace in the Hole”, by having a plane take off so fast, it throws away all of its camouflage paint.) After more bucking, Jerry is thrown from the driver’s seat, and Tom plays cat and mouse games appropriate to his species by having the engine creep up upon Jerry step by step, race after him at full speed (with brief stops to let Jerry catch his breath), and even open its bumpers like jaws to snap at Jerry’s tail. Jerry finally reaches a display counter and scrambles up its side. At the top is a product which couldn’t be more formidable – bowling balls! Jerry dislodges one, sending it rolling toward the edge. The engine, looking up with its headlight eyes, sees the sphere coming (another POV perspective shot), and runs for cover, yipping like a wounded dog. The ball meanwhile rolls to the entrance steps of an upward-bound escalator, then rolls off at a landing above. It collides with the base of a half-mannequin (its lower half oddly consisting of a base with curved bottom like a roly-poly). The mannequin tips sideways, knocking a large planter vase off the other end of the platform, which falls in perspective toward ground level – directly over Tom’s head. The cat raises his eyes to see it, and barely flinches. Refusing to lose his cool, Tom calmly stands without so much as a twitch of a whisker, raises his arms, and catches the vase, a few inches above his head. Tom gives us a confident eyebrow raise, as if to say “And you thought that…” But Jones has double-loaded the gag on Tom, as the bowling ball also reaches the edge of the platform above, and falls on the identical trajectory as the vase – right through the vase’s bottom, and clunk onto Tom’s head – producing a gray lump that extends through one of the holes in the ball.

Tom is next seen hiding behind a column, on the lookout for Jerry. He emerges, with his yards of tail coiled around his lower torso, as if wearing a newly-knit pair of gray trousers. Suddenly, his backside is bathed in that same headlight glow we’ve seen twice before. Indoors? Well, not exactly, as this time, the light is not from a trolley car, but from a toy fire engine that Jerry has acquired from the toy department. Tom has so little time to react that his fingertips barely touch the blindfold before he is clobbered again. Tom is flipped into the air, and like his predecessor Claude Cat in many a Jones epic with Frisky Puppy, clings upside down on the ceiling, his teeth chattering and fur frazzled. Jerry gives him a coy wave as he passes, but Tom’s eyes have something else in view, as he slides back to ground level via one of the marble columns. A display of the fire engines is set up in the toy department, prominently featuring a device Jerry didn’t make use of – a remote control for the vehicles. Tom selects one of the control boxes, and presses a button. Jerry’s engine immediately screeches to a stop, so fast it loses its ladder, front fenders, and other components. Another push, and the vehicle shifts into reverse, then stops cold again, throwing off its clanging bell. (This throwing off of accessories is an interesting way to make the job simpler for the animators in the action that follows, reducing the engine to bare bones to save on line detail – a technique once previously used by Alex Lovy in Woody Woodpecker’s “Ace in the Hole”, by having a plane take off so fast, it throws away all of its camouflage paint.) After more bucking, Jerry is thrown from the driver’s seat, and Tom plays cat and mouse games appropriate to his species by having the engine creep up upon Jerry step by step, race after him at full speed (with brief stops to let Jerry catch his breath), and even open its bumpers like jaws to snap at Jerry’s tail. Jerry finally reaches a display counter and scrambles up its side. At the top is a product which couldn’t be more formidable – bowling balls! Jerry dislodges one, sending it rolling toward the edge. The engine, looking up with its headlight eyes, sees the sphere coming (another POV perspective shot), and runs for cover, yipping like a wounded dog. The ball meanwhile rolls to the entrance steps of an upward-bound escalator, then rolls off at a landing above. It collides with the base of a half-mannequin (its lower half oddly consisting of a base with curved bottom like a roly-poly). The mannequin tips sideways, knocking a large planter vase off the other end of the platform, which falls in perspective toward ground level – directly over Tom’s head. The cat raises his eyes to see it, and barely flinches. Refusing to lose his cool, Tom calmly stands without so much as a twitch of a whisker, raises his arms, and catches the vase, a few inches above his head. Tom gives us a confident eyebrow raise, as if to say “And you thought that…” But Jones has double-loaded the gag on Tom, as the bowling ball also reaches the edge of the platform above, and falls on the identical trajectory as the vase – right through the vase’s bottom, and clunk onto Tom’s head – producing a gray lump that extends through one of the holes in the ball.

More hijinks ensue, with Jerry hiding out in a display of toy stuffed mice (all identical to himself), in similar fashion to Sniffles the Mouse’s ducking among Porky Pig dolls in “Toy Trouble” (1941), until a yank by Tom on his tail produces a “Yeow” instead of “Mama”. Tom places Jerry in painful peril as the ball in a game of table-tennis, swift Tom playing the game from both sides of the table (as did Max Hare on the tennis court in Disney’s The Tortoise and the Hare (1935)). Jerry gets caught in the net, which stretches like a slingshot – but manages to grab a wooden croquet mallet from a wall display, delivering a shot right into Tom’s face by way of another POV camera angle. Tom flies backwards from the blow, while Jerry regains his fire engine (now with no one to interfere by pressing buttons on the remote) and races ahead of the sailing Tom. Scampering up onto a counter, Jerry opens the end-hatch of a vacuum-tube system (used in old department stores to convey orders to departments via messages in cylindrical cannisters). Tom flies straight into the tube, is conveyed through a maze of pipes, shoots out the other end (compressed into a cylinder), and down an open elevator shaft. At the base of the elevator waits Jerry, with a large spring placed in the elevator bed directly under Tom (who again approaches in POV angle). Tom bounces off the spring, and out the mail slot of the front door, back onto the trolley tracks outside. You guessed it. Another beam of light hits Tom. He again fastens on his blindfold, preparing for the worst – but this time the trolley passes right by, on a second track! Why? At the track switch stands Jerry, having just pulled the lever to save Tom’s neck. Much like the Road Runner holding up a sign reading “I haven’t got the heart”, Jerry explains his own behavior to the audience by proving that he is an “angel” at heart, sprouting a halo and wings. He looks at these new appurtenances, then decides, why not make good use of them? – and flies away down the track to horizon, for the iris out.

More hijinks ensue, with Jerry hiding out in a display of toy stuffed mice (all identical to himself), in similar fashion to Sniffles the Mouse’s ducking among Porky Pig dolls in “Toy Trouble” (1941), until a yank by Tom on his tail produces a “Yeow” instead of “Mama”. Tom places Jerry in painful peril as the ball in a game of table-tennis, swift Tom playing the game from both sides of the table (as did Max Hare on the tennis court in Disney’s The Tortoise and the Hare (1935)). Jerry gets caught in the net, which stretches like a slingshot – but manages to grab a wooden croquet mallet from a wall display, delivering a shot right into Tom’s face by way of another POV camera angle. Tom flies backwards from the blow, while Jerry regains his fire engine (now with no one to interfere by pressing buttons on the remote) and races ahead of the sailing Tom. Scampering up onto a counter, Jerry opens the end-hatch of a vacuum-tube system (used in old department stores to convey orders to departments via messages in cylindrical cannisters). Tom flies straight into the tube, is conveyed through a maze of pipes, shoots out the other end (compressed into a cylinder), and down an open elevator shaft. At the base of the elevator waits Jerry, with a large spring placed in the elevator bed directly under Tom (who again approaches in POV angle). Tom bounces off the spring, and out the mail slot of the front door, back onto the trolley tracks outside. You guessed it. Another beam of light hits Tom. He again fastens on his blindfold, preparing for the worst – but this time the trolley passes right by, on a second track! Why? At the track switch stands Jerry, having just pulled the lever to save Tom’s neck. Much like the Road Runner holding up a sign reading “I haven’t got the heart”, Jerry explains his own behavior to the audience by proving that he is an “angel” at heart, sprouting a halo and wings. He looks at these new appurtenances, then decides, why not make good use of them? – and flies away down the track to horizon, for the iris out.

Darn Barn (Terrytoons/Fox, Possible Possum, 6/1/65 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – An unexplained disaster has struck. A barn owned by the General (owner of the “General Store”), has caught fire. Billy Bear alerts Possible Possum of the news only after distraction of listening to Possum’s latest song composition, and by the time the two arrive at the scene with a water bucket, there is nothing left to douse but the remaining ashes and embers. Following Southern tradition, Possible and the rest of his gang of animals volunteer to rebuild the structure in a barn raising, for which the General promises to open the store for a free celebratory banquet. However, there is one opposed to this whole idea – Hill the Builder, the only contractor in the county, who insists that they are taking money right out from his pockets. The gang ignores his protests, and rounds up a substantial pile of boards and nails to begin construction. En route with their load to the barn site, they are intercepted by Hill and his truck, who claims that there are “no hard feelings,” and offers them a ride with their load to the site. Everyone and everything gets piled into the rear of Hill’s truck – but Hill unexpectedly shifts into reverse gear, backs the truck up to the edge of a high cliff, and dumps the entire load over the side, Possum’s gang and all, into a canyon. From a large mud puddle in which the boys land, Billy Bear states that this gets his “dander up”, and retaliates by bending back a board to use as a catapult, flinging a large mud glob into Hill’s face as he drives away, causing him to wreck his truck in a crash with a tree. “I’m not licked yet”, promises Hill.

Darn Barn (Terrytoons/Fox, Possible Possum, 6/1/65 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – An unexplained disaster has struck. A barn owned by the General (owner of the “General Store”), has caught fire. Billy Bear alerts Possible Possum of the news only after distraction of listening to Possum’s latest song composition, and by the time the two arrive at the scene with a water bucket, there is nothing left to douse but the remaining ashes and embers. Following Southern tradition, Possible and the rest of his gang of animals volunteer to rebuild the structure in a barn raising, for which the General promises to open the store for a free celebratory banquet. However, there is one opposed to this whole idea – Hill the Builder, the only contractor in the county, who insists that they are taking money right out from his pockets. The gang ignores his protests, and rounds up a substantial pile of boards and nails to begin construction. En route with their load to the barn site, they are intercepted by Hill and his truck, who claims that there are “no hard feelings,” and offers them a ride with their load to the site. Everyone and everything gets piled into the rear of Hill’s truck – but Hill unexpectedly shifts into reverse gear, backs the truck up to the edge of a high cliff, and dumps the entire load over the side, Possum’s gang and all, into a canyon. From a large mud puddle in which the boys land, Billy Bear states that this gets his “dander up”, and retaliates by bending back a board to use as a catapult, flinging a large mud glob into Hill’s face as he drives away, causing him to wreck his truck in a crash with a tree. “I’m not licked yet”, promises Hill.

Possible stands guard while first construction commences, but catches sight of Hill on a distant cliff, working with a lever to launch a boulder down the cliffside to flatten the new construction. Possible races to the scene before Hill can get the boulder loose, tunnels under the cliff, and uses a pick axe to undermine the cliff edge where Hill is standing (a basic Wile E. Coyote situation). Hill and the boulder bounce down the slope together, with Hill in the lead, his body running interference to stop the boulder’s roll just short of its intended target. One two-by-four is dislodged by Hill’s efforts in frustration to shake the structure down, and cracks in two over Hill’s head, leaving him grumbling as he walks away.

Possible stands guard while first construction commences, but catches sight of Hill on a distant cliff, working with a lever to launch a boulder down the cliffside to flatten the new construction. Possible races to the scene before Hill can get the boulder loose, tunnels under the cliff, and uses a pick axe to undermine the cliff edge where Hill is standing (a basic Wile E. Coyote situation). Hill and the boulder bounce down the slope together, with Hill in the lead, his body running interference to stop the boulder’s roll just short of its intended target. One two-by-four is dislodged by Hill’s efforts in frustration to shake the structure down, and cracks in two over Hill’s head, leaving him grumbling as he walks away.

Macon Mouse is next to maintain surveillance upon Hill. Hill (whose truck has now been repaired) has acquired a harpoon gun, mounted into the rear of his truck, and takes aim at the barn with a grappling hook and rope loaded in the gun’s muzzle. He plans to hook the barn, then drag it apart with his truck. However, Macon Mouse hides inside the coil of rope, bites the line from the grappling hook short, and ties it off to the rear suspension of the truck. When the gun is fired, the hook and rope drag the truck along with it, through the air and into a crash just short of the barn. Billy Bear opens the barn door, as the remains of the rear of the truck and harpoon gun, carrying Hill along, roll through and crash into the back wall of the barn, not causing the structure any damage. :You’ve gotta admit, she’s built pretty solid”, says Billy, as the frustrated Hill exits again.

The barn is finally finished, and the boys eagerly anticipate informing the General – until Hill slips up to the back side of the structure, with another grappling hook, a chain, and a strong tractor, planning to tear the entire thing down. As Hill starts up his tractor, Possible spors the hook caught in the framework of the upper floor landing. Deducing Hill’s plans, Possible tosses the metal hook away, landing it atop a line of high-voltage power wires running aside the road behind the barn. Sparks fly from the hook down the metal chain and into the tractor, lighting up Hill in multiple colors like a neon sign. As the tractor proceeds down the road, the voltage remains inescapable, with the metal hook sliding along the wires in the same manner as the power pole of an electric trolley, leaving Hill glued to the steering wheel for as far as the wires are strung. At the banquet that night, the General asks if Hill gave them any trouble. “Oh, ge was around”, the gang responds. “What’d he think of your work?” the General asks. Possible replies, “I think he got a real charge out of it”, as the gang laughs, while the General, not in on the joke, scratches his head in puzzlement.

The barn is finally finished, and the boys eagerly anticipate informing the General – until Hill slips up to the back side of the structure, with another grappling hook, a chain, and a strong tractor, planning to tear the entire thing down. As Hill starts up his tractor, Possible spors the hook caught in the framework of the upper floor landing. Deducing Hill’s plans, Possible tosses the metal hook away, landing it atop a line of high-voltage power wires running aside the road behind the barn. Sparks fly from the hook down the metal chain and into the tractor, lighting up Hill in multiple colors like a neon sign. As the tractor proceeds down the road, the voltage remains inescapable, with the metal hook sliding along the wires in the same manner as the power pole of an electric trolley, leaving Hill glued to the steering wheel for as far as the wires are strung. At the banquet that night, the General asks if Hill gave them any trouble. “Oh, ge was around”, the gang responds. “What’d he think of your work?” the General asks. Possible replies, “I think he got a real charge out of it”, as the gang laughs, while the General, not in on the joke, scratches his head in puzzlement.

Donald’s Fire Survival Plan (Disney, 8/1/66 – Les Clark, dir.), was neither a theatrical nor made for television, but one of those films destined for recurrent rental or purchase by various school districts as a strictly educational resource. As with the “I’m No Fool” film featured earlier in these articles, it was “revised” in the 1980’s with new live-action footage, removing all content of the original featuring Walt himself, destroying its charm. Accept no substitutes but the original version.

Donald’s Fire Survival Plan (Disney, 8/1/66 – Les Clark, dir.), was neither a theatrical nor made for television, but one of those films destined for recurrent rental or purchase by various school districts as a strictly educational resource. As with the “I’m No Fool” film featured earlier in these articles, it was “revised” in the 1980’s with new live-action footage, removing all content of the original featuring Walt himself, destroying its charm. Accept no substitutes but the original version.

As in The Wonderful World of Color, Disney appears in person for live-action wraparounds in the original, stressing the dangers of the domicile fire and the fact that, while a house can be replaced, kids cannot. He thus sets up a little tale, turning in reverse on a TV monitor footage of a house collapsing in flame, back to when it was standing unscathed, and regressing the image further into the animated form of the abode where Donald and his nephews reside. The kids appear, possibly for the first time with understandable junior voices not provided by Clarence Nash. (They would subsequently appear with these same voices in the “Wonderful World of Color” show, “The Ranger’s Guide To Nature”, and in the theatrical short, “Scrooge McDuck and Money”.) The kids are drawing up a fire escape plan at the suggestion of their teacher, and attempt to obtain Donald’s input on escape routes, a meeting place outside, etc. Donald, however, is too engrossed in heavy reading (a pulp magazine entitled “Monster Tales”), to be bothered with their interruptions. “Teacher says! Teacher says!”, he complains, sending the irritating kids upstairs to bed while he continues with his reading. Suddenly, a small spark, shaped like a flame, creeps down the shaft of a lamp pole, and transforms into a little duck fireman. Blowing an emergency whistle, he startles Donald out of his chair, then introduces himself as the voice of Donald’s inner common-sense. He chastises Donald for being so hard on and inattentive to the kids. “What d’ya send them to school for, if you don’t want them to listen to the teacher?” He attempts to emphasize how important it is to know how to get out of the house. “I know how to get out of my house”, Donald squawks. “With a fire going on, Charlie? Uh uhh”, responds the little fireduck. Grabbing Donald by the hand, the fireduck floats Donald to various vantage points to observe hazards within the home, including frayed wiring on his living room lamp next to a carpet and an overstuffed chair, which could generate sparks, heat, and internally smolder to fill the house with smoke before any open flames would erupt. Open doors to the stairwell and into the bedrooms above are illustrated to have the effect of a chimney in bringing the smoke upstairs, where it will gather against the ceiling.

The effects of carbon monoxide and other poison gasses are demonstrated on a phantom Donald in bed upstairs, knocking him out in a few breaths upon rising from bed, and potentially leading to his soul exiting his body, playing an angel harp. The fireduck pushes the soul back into phantom Donald to give him a second chance. Supposing the hall door had been closed instead of open, he lets the duck try to escape. Phantom Donald foolishly yanks the door open without testing it for heat first, and lets in super-heated air from the flame, again transforming him into an angel. Another pushback of Donald’s soul allows Phantom Donald a third chance. Donald wastes time trying to rescue old memorabilia, while the fireduck tells him, “Forget it. You gotta get out, quick.” The window is the only escape left, but Donald forgets he’s on the second floor, and one jump produces another angel. A final push back, and Donald is restored to his living room in the present, with the reminder “You can take chances, but what about the kids?” Donald posts the kids’ plan on a bulletin board, annotates it for problems and hazards to be fixed (adding portable window extension ladders, alternate exit points from rooms, fixing wires, positioning a large ladder in the garage to allow for potential outside help, etc. He runs a drill with the kids, making sure they know not to hide under the bed or in a closet when they’re scared, and counts noses at a communal meeting point. The fireduck reappears, adding, “Supposing this wasn’t only a drill?”, causing Donald to look back to see the beginnings of smoke billowing out the windows. The ducks figure out where their local fire alarm box is located, but when Donald opens up the alarm box door, he is reassured by the fireduck inside the box that he has already called the fire department. The important thing is that everybody is safe. Donald closes the door, as one of the nephews asks him who he was talking to. “Oh, just a friend of mine”, responds Donald, looking inside the box again to find no one inside. Don shrugs his shoulders to the camera in confusion, as the scene returns to the real world for closing remarks by Disney, aided by the fireduck who joins him from out of the TV monitor, for the fade out.

The effects of carbon monoxide and other poison gasses are demonstrated on a phantom Donald in bed upstairs, knocking him out in a few breaths upon rising from bed, and potentially leading to his soul exiting his body, playing an angel harp. The fireduck pushes the soul back into phantom Donald to give him a second chance. Supposing the hall door had been closed instead of open, he lets the duck try to escape. Phantom Donald foolishly yanks the door open without testing it for heat first, and lets in super-heated air from the flame, again transforming him into an angel. Another pushback of Donald’s soul allows Phantom Donald a third chance. Donald wastes time trying to rescue old memorabilia, while the fireduck tells him, “Forget it. You gotta get out, quick.” The window is the only escape left, but Donald forgets he’s on the second floor, and one jump produces another angel. A final push back, and Donald is restored to his living room in the present, with the reminder “You can take chances, but what about the kids?” Donald posts the kids’ plan on a bulletin board, annotates it for problems and hazards to be fixed (adding portable window extension ladders, alternate exit points from rooms, fixing wires, positioning a large ladder in the garage to allow for potential outside help, etc. He runs a drill with the kids, making sure they know not to hide under the bed or in a closet when they’re scared, and counts noses at a communal meeting point. The fireduck reappears, adding, “Supposing this wasn’t only a drill?”, causing Donald to look back to see the beginnings of smoke billowing out the windows. The ducks figure out where their local fire alarm box is located, but when Donald opens up the alarm box door, he is reassured by the fireduck inside the box that he has already called the fire department. The important thing is that everybody is safe. Donald closes the door, as one of the nephews asks him who he was talking to. “Oh, just a friend of mine”, responds Donald, looking inside the box again to find no one inside. Don shrugs his shoulders to the camera in confusion, as the scene returns to the real world for closing remarks by Disney, aided by the fireduck who joins him from out of the TV monitor, for the fade out.

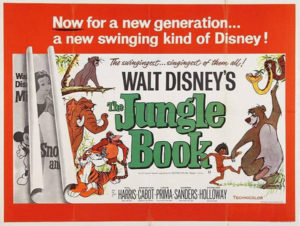

Several 2-D features in the following years made use of fire in their climaxes. Disney’s The Jungle Book (10/18/67, Wolfgang Reitherman, dir.) faces-off man-cub Mowgli with fierce tiger Shere Kahn for a showdown in its penultimate sequence. Mowgli stands his ground bravely, insisting he won’t run from anyone. To make it sporting, Shere Kahn, intending to play cat and mouse, gives Mowgli a count of ten during which to flee. Instead, Mowgli grabs a large stick to use as a club, and prepares to do mismatched battle. Fortunately, Mowgli is not quite alone. A quartet of singing buzzards (with Beatle hairdos, yet) are too chicken to immediately enter the fray, but remain watching on the limbs of a nearby tree. Also, and without fear, approaches Baloo the Bear, who has been searching for Mowgli for many days. Arriving in the nick of time, Baloo grabs hold of the tiger’s tail, just as the beast pounces – causing Kahn to fall short of his intended prey by mere inches. “Run, Mowgli, run”, shouts Baloo. Mowgli finally does what he is told, leading Kahn on a chase, while Baloo hangs on desperately, with a literal “tiger by the tail”, avoiding as best he can Kahn’s circling attacks with jaws and claws. Mowgli assists while the tiger is distracted by Baloo, getting in a few good whacks on the tiger’s nose with his stick, but Kahn turns and again pursues Mowgli – bear or no bear in tow. “Somebody do somethin’ with that kid”, calls out Baloo, while getting dragged over rocks and smashing into tree limbs. The buzzards are finally roused into action, swoop down ahead of Kahn, and pick up Mowgli by the arms, flying him upwards out of Kahn’s reach. “He’s safe now”, calls one of the buzzards to Baloo, telling him he can now let go of Kahn. “Are you kiddin’? There’s teeth in the other end”, responds Baloo. Baloo’s chin suddenly gets caught in the crotch of a tree branch, bringing both tiger and bear to a standstill. Kagn grabs Baloo with his front paws and flings the bear to the ground. “I’ll kill you for this”, declares Kahn, and begins slashing with razor-claws across Baloo. “Baloo needs help”, calls out Mowgli from above. Help comes from divine intervention, as a rising storm sends down a bolt of lightning, setting fire to an old tree. “Fire! That’s it! It’s the only thing old stripes is afraid of”, declares one of the vultures. “You get the fire, we’ll do the rest”, utters another to Mowgli, setting him down on the ground. Mowgli grabs hold of the base of a large branch, its leaves glowing in a bright blaze, and also grabs a length of jungle vine. As Baloo receives what may be his final blow, the buzzards put up an interference, flapping around Kahn’s head just out of claw reach, and even plucking at his whiskers when they can get in close enough. While this is going on, Mowgli slips up behind Kahn, takes hold of his tail, and quickly ties a loop of the vine around the tree limb, to fasten it to Kahn’s tail. “Look behind you, chum”, says one of the vultures to Kahn. Kahn sees the flames in close proximity to his person, and panics. He runs a few feet forward, but the flames lick at his rear. He stops, batting at the flaming branch with his front paws in attempt to smother it, but has no effect. With no other recourse, he runs, and runs, and runs, the flames continuing to make contact with his rear, producing loud roars of pain, as the tiger disappears to horizon, never to be seen again (at least, not until “Talespin”).

Several 2-D features in the following years made use of fire in their climaxes. Disney’s The Jungle Book (10/18/67, Wolfgang Reitherman, dir.) faces-off man-cub Mowgli with fierce tiger Shere Kahn for a showdown in its penultimate sequence. Mowgli stands his ground bravely, insisting he won’t run from anyone. To make it sporting, Shere Kahn, intending to play cat and mouse, gives Mowgli a count of ten during which to flee. Instead, Mowgli grabs a large stick to use as a club, and prepares to do mismatched battle. Fortunately, Mowgli is not quite alone. A quartet of singing buzzards (with Beatle hairdos, yet) are too chicken to immediately enter the fray, but remain watching on the limbs of a nearby tree. Also, and without fear, approaches Baloo the Bear, who has been searching for Mowgli for many days. Arriving in the nick of time, Baloo grabs hold of the tiger’s tail, just as the beast pounces – causing Kahn to fall short of his intended prey by mere inches. “Run, Mowgli, run”, shouts Baloo. Mowgli finally does what he is told, leading Kahn on a chase, while Baloo hangs on desperately, with a literal “tiger by the tail”, avoiding as best he can Kahn’s circling attacks with jaws and claws. Mowgli assists while the tiger is distracted by Baloo, getting in a few good whacks on the tiger’s nose with his stick, but Kahn turns and again pursues Mowgli – bear or no bear in tow. “Somebody do somethin’ with that kid”, calls out Baloo, while getting dragged over rocks and smashing into tree limbs. The buzzards are finally roused into action, swoop down ahead of Kahn, and pick up Mowgli by the arms, flying him upwards out of Kahn’s reach. “He’s safe now”, calls one of the buzzards to Baloo, telling him he can now let go of Kahn. “Are you kiddin’? There’s teeth in the other end”, responds Baloo. Baloo’s chin suddenly gets caught in the crotch of a tree branch, bringing both tiger and bear to a standstill. Kagn grabs Baloo with his front paws and flings the bear to the ground. “I’ll kill you for this”, declares Kahn, and begins slashing with razor-claws across Baloo. “Baloo needs help”, calls out Mowgli from above. Help comes from divine intervention, as a rising storm sends down a bolt of lightning, setting fire to an old tree. “Fire! That’s it! It’s the only thing old stripes is afraid of”, declares one of the vultures. “You get the fire, we’ll do the rest”, utters another to Mowgli, setting him down on the ground. Mowgli grabs hold of the base of a large branch, its leaves glowing in a bright blaze, and also grabs a length of jungle vine. As Baloo receives what may be his final blow, the buzzards put up an interference, flapping around Kahn’s head just out of claw reach, and even plucking at his whiskers when they can get in close enough. While this is going on, Mowgli slips up behind Kahn, takes hold of his tail, and quickly ties a loop of the vine around the tree limb, to fasten it to Kahn’s tail. “Look behind you, chum”, says one of the vultures to Kahn. Kahn sees the flames in close proximity to his person, and panics. He runs a few feet forward, but the flames lick at his rear. He stops, batting at the flaming branch with his front paws in attempt to smother it, but has no effect. With no other recourse, he runs, and runs, and runs, the flames continuing to make contact with his rear, producing loud roars of pain, as the tiger disappears to horizon, never to be seen again (at least, not until “Talespin”).

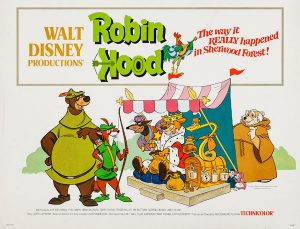

Robin Hood (Disney, 11/8/73 – Wolfgang Reitherman, dir.). In its climactic sequence, Robin (a fox) and Little John (a bear) stage a jail break of the tax-depleted citizenry of Nottingham right out from under the noses of the Sheriff and his assistant Trigger (a vulture trigger-happy to shoot off his crossbow). John acts as steed to pull a wagon of the freed citizens through the castle gates, but one of the townsfolk is accidentally left behind – the smallest member of the rabbit family. Robin races back inside the gates to retrieve the child, but a Captain of the Guard severs a chain on the portcullis gate at the castle entrance, causing it to fall to block Robin’s escape. Robin hands the child through the openings of the gate to John, and tells him to get going with the townsfolk and not to worry about him. John does as ordered, leaving Robin to face the Sheriff’s men and royal guards alone. The rhino guards charge the gate in a line. Robin avoids their axes by climbing the portcullis grill, then swinging over to a tower wall on a rope. Arrows fly, lodging in the wall above him, and Robin uses the arrows as ladder rungs to climb to the top of the wall. Two of the Sheriff’s men launch arrows at him from opposite directions, but Robin ducks in the middle, causing the arrows to barely miss each of the respective archers. Robin continues scaling walls to Prince John’s bedchamber, continuing to avoid shot along the way. However, the Sheriff enters the tower from a staircase below, carrying a torch. As Robin enters the bedchamber from a balcony and pulls a pair of velvet curtains shut, he is surprised to find the Sheriff already there, waving his fiery torch threateningly in Robin’s face, while reaching for his sword with his other hand. The flames catch the curtains on fire, and the flames spread as Robin and the Sheriff duel. Robin obtains an advantage by ducking under a sword thrust, and pulling a carpet out from under the Sheriff, then races for an internal staircase leading to the top of the tower. The fire rages, burning remnants of more curtains across the path of the exit to the staircase, causing the Sheriff not to follow. As Robin ascends, so do the flames, drawing more threateningly near, leaving Robin no avenue of escape except a small tower window. Climbing along the rocky sides of the tower, Robin makes his way to the conical roof, but the fire continues to spread through the tower window, and begins to burn through the roof structure. Robin clings to a central pole at the roof’s peak, but it is quickly becoming apparent to all observers, including Robin, that time is running out. As the flames lick perilously close to Robin’s fur, the time for desperate action arrives, and Robin takes a leap – about five stories down, into the castle moat.

Robin Hood (Disney, 11/8/73 – Wolfgang Reitherman, dir.). In its climactic sequence, Robin (a fox) and Little John (a bear) stage a jail break of the tax-depleted citizenry of Nottingham right out from under the noses of the Sheriff and his assistant Trigger (a vulture trigger-happy to shoot off his crossbow). John acts as steed to pull a wagon of the freed citizens through the castle gates, but one of the townsfolk is accidentally left behind – the smallest member of the rabbit family. Robin races back inside the gates to retrieve the child, but a Captain of the Guard severs a chain on the portcullis gate at the castle entrance, causing it to fall to block Robin’s escape. Robin hands the child through the openings of the gate to John, and tells him to get going with the townsfolk and not to worry about him. John does as ordered, leaving Robin to face the Sheriff’s men and royal guards alone. The rhino guards charge the gate in a line. Robin avoids their axes by climbing the portcullis grill, then swinging over to a tower wall on a rope. Arrows fly, lodging in the wall above him, and Robin uses the arrows as ladder rungs to climb to the top of the wall. Two of the Sheriff’s men launch arrows at him from opposite directions, but Robin ducks in the middle, causing the arrows to barely miss each of the respective archers. Robin continues scaling walls to Prince John’s bedchamber, continuing to avoid shot along the way. However, the Sheriff enters the tower from a staircase below, carrying a torch. As Robin enters the bedchamber from a balcony and pulls a pair of velvet curtains shut, he is surprised to find the Sheriff already there, waving his fiery torch threateningly in Robin’s face, while reaching for his sword with his other hand. The flames catch the curtains on fire, and the flames spread as Robin and the Sheriff duel. Robin obtains an advantage by ducking under a sword thrust, and pulling a carpet out from under the Sheriff, then races for an internal staircase leading to the top of the tower. The fire rages, burning remnants of more curtains across the path of the exit to the staircase, causing the Sheriff not to follow. As Robin ascends, so do the flames, drawing more threateningly near, leaving Robin no avenue of escape except a small tower window. Climbing along the rocky sides of the tower, Robin makes his way to the conical roof, but the fire continues to spread through the tower window, and begins to burn through the roof structure. Robin clings to a central pole at the roof’s peak, but it is quickly becoming apparent to all observers, including Robin, that time is running out. As the flames lick perilously close to Robin’s fur, the time for desperate action arrives, and Robin takes a leap – about five stories down, into the castle moat.

Being of a hero’s constitution, Robin easily survives the dive, but Prince John’s orders to “Kill him!” ring in his ears. A volley of arrows from archers on the wall hit the water, causing Robin to dive, seemingly only inches ahead of the arrows’ fall. A trail of bubbles marks his point of descent, which begin to diminish in frequency, then deplete entirely – as Robin’s hat floats to the surface, with an arrow point planted firmly in it. On the banks of the moat, John and one of the small rabbits wait with hope that fades quickly as the hat becomes visible. “No. Oh, no”, utters John involuntarily, trying to conceal his own despair and figure how to most gently break the terrible news to the child. “He’s gonna make it, isn’t he?”, asks the rabbit, leaving John at an entire loss for words. Realization begins to hit the rabbit too, and he clings to John’s sleeve, about to break into tears – when something catches his eye. The end of a small reed approaches in the water. As it reaches the shore, a jet of water shoots out of it into John’s face. It is Robin. “Ooh, did you have me worried, Rob. I thought you were long gone”, breathes John in a sign of relief. “I bet he coulda swum twice that far”, says the rabbit, hugging Robin, who smiles in return, with an expression registering that he is not exactly sure he could in fact have lived up to the rabbit’s boast. “Oh, no! It’s so miserably unfair!”, moans Prince John from the wall in dazed despair. Sir Hiss, his long-suffering right hand man (that is, snake), also points out the raging blaze within the structure. “And now look what you’ve done to your mother’s castle.” The Prince, who throughout the picture has exhibited a “mother complex” prompting him to violent outbursts coupled with thumb-sucking at the mention of her name, goes off the deep end, and takes out his rage on Hiss, swatting at him violently with a large stick, and uttering epithets at him such as “Procrastinating python! You eel in snake’s clothing!” He chases Hiss up the castle steps, back into the burning building, as Hiss calls to anyone who will hear, “Help! He’s gone stark raving M-A-A-A-A-D!”

Being of a hero’s constitution, Robin easily survives the dive, but Prince John’s orders to “Kill him!” ring in his ears. A volley of arrows from archers on the wall hit the water, causing Robin to dive, seemingly only inches ahead of the arrows’ fall. A trail of bubbles marks his point of descent, which begin to diminish in frequency, then deplete entirely – as Robin’s hat floats to the surface, with an arrow point planted firmly in it. On the banks of the moat, John and one of the small rabbits wait with hope that fades quickly as the hat becomes visible. “No. Oh, no”, utters John involuntarily, trying to conceal his own despair and figure how to most gently break the terrible news to the child. “He’s gonna make it, isn’t he?”, asks the rabbit, leaving John at an entire loss for words. Realization begins to hit the rabbit too, and he clings to John’s sleeve, about to break into tears – when something catches his eye. The end of a small reed approaches in the water. As it reaches the shore, a jet of water shoots out of it into John’s face. It is Robin. “Ooh, did you have me worried, Rob. I thought you were long gone”, breathes John in a sign of relief. “I bet he coulda swum twice that far”, says the rabbit, hugging Robin, who smiles in return, with an expression registering that he is not exactly sure he could in fact have lived up to the rabbit’s boast. “Oh, no! It’s so miserably unfair!”, moans Prince John from the wall in dazed despair. Sir Hiss, his long-suffering right hand man (that is, snake), also points out the raging blaze within the structure. “And now look what you’ve done to your mother’s castle.” The Prince, who throughout the picture has exhibited a “mother complex” prompting him to violent outbursts coupled with thumb-sucking at the mention of her name, goes off the deep end, and takes out his rage on Hiss, swatting at him violently with a large stick, and uttering epithets at him such as “Procrastinating python! You eel in snake’s clothing!” He chases Hiss up the castle steps, back into the burning building, as Hiss calls to anyone who will hear, “Help! He’s gone stark raving M-A-A-A-A-D!”

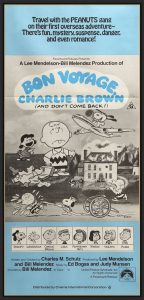

Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don’t Come Back) (Lee Mendelson – Bill Melendez/Paramount, 5/30/80 – Bill Melendez, dir.) – While Charles Schulz took the writing credit on this picture, one wonders how much he truly had to do with it, as this film seems to violate most of the primary book of rules which otherwise guided the stories for the franchise. It was the first Peanuts production to break the rule that adults were never seen, and only heard through the squawking sounds of a muted trombone. Here, instead, we see full images including faces of grandparents of Charlie Brown by way of photograph, a fully visible and audible taxi driver, and silhouettes of others including a hermit-like Baron (not the Red Baron), whose voice is heard normally in full dialogue. (The breaking of the “no adult” rule would not occur again until Melendez’s own project

Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don’t Come Back) (Lee Mendelson – Bill Melendez/Paramount, 5/30/80 – Bill Melendez, dir.) – While Charles Schulz took the writing credit on this picture, one wonders how much he truly had to do with it, as this film seems to violate most of the primary book of rules which otherwise guided the stories for the franchise. It was the first Peanuts production to break the rule that adults were never seen, and only heard through the squawking sounds of a muted trombone. Here, instead, we see full images including faces of grandparents of Charlie Brown by way of photograph, a fully visible and audible taxi driver, and silhouettes of others including a hermit-like Baron (not the Red Baron), whose voice is heard normally in full dialogue. (The breaking of the “no adult” rule would not occur again until Melendez’s own project at the time of the Bicentennial 1988’s This Is America, Charlie Brown, necessitating the meeting of the Peanuts gang with various historical figures of the past.) Additionally, the script bogs down in attempting to establish a mystery plot, as well as placing members of the cast in dramatic danger from a chateau fire – situations much too heavy-handed and serious to seem proper subjects for inclusion in a Peanuts cartoon.

In a convoluted plot never entirely explained satisfactorily in its exposition, Charlie Brown receives a letter in French from a girl unknown to him, just as he and Linus are somehow selected as representatives of the school in a foreign exchange program. The letter invires them to stay their two weeks in France at a remote chateau. However, when they arrive, they face a locked gate, and a chateau that appears empty and deserted, except for a recurring candlelight from an upper-story room. I did not have the patience to sit through again the whole of how Linus finally penetrates the chateau, and confronts the occupant of the room – a little girl, who is discovered to have been the author of the letter. It is disclosed that the girl’s uncle, a reclusive Baron, hates visitors, and would be angered to find them inside the chateau grounds. Despite this knowledge, the girl had heard tales long ago from her grandmother of a “handsome American” she met in the great war, who almost became her husband, but returned to the states after the war instead. Both eventually married separately, and the American became the grandfather of Charlie Brown. Having somehow learned through contacts with others who had visited America of the whereabouts of the Brown family, the girl had sent the invitation, hoping that her uncle would not be upset – but was proven wrong by the uncle’s sealing off of the chateau and instruction to her to keep hidden and not let them in. If this all makes sense to you, maybe you should become a hack writer yourself! Anyway, the girl’s candle gets knocked over, and a fire starts in her attic room. Linus and the girl call for help out the window.