Today’s offerings include a well-known feature, and many lesser-known installments from major and minor studios. Among highlights are two notable but largely-forgotten Columbia efforts contributed to by Frank Tashlin, both as studio supervisor, and as screenwriter of one under his favorite pseudonym, “Tish Tash.”

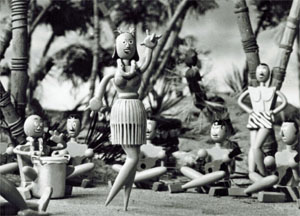

I am uncertain as to when George Pal’s South Sea Sweethearts hit American screens, but presume it was shortly following the first releases of his American-produced “Madcap Models” series for Paramount, during 1941. The film had originally been created in 1938, as part of a series of “soft-sell” full-length advertising films for Horlick’s malted milk – a product pushed as a medicinal remedy for “night starvation”, that was supposed to restore energy to those who woke up tired and stayed tired, if taken before bed for six weeks. (Sometimes I’ve felt I could use a little of the stuff myself.) It was the only one of such European films selected by Paramount as something to pad out a gap in production schedule. New titles were spliced on and/or superimposed to add Paramount’s logos and indicia, and, oddly enough, as the Horlick’s product was apparently not marketed in the states, the “soft-sell” sales pitch footage was left in, Paramount feeling no one unfamiliar with the product would recognize the film as a commercial, but merely accept the item as the same kind of generic wonder potion one might acquire from a hawker at a medicine show.

The film receives a brief honorable mention here for a little atmospheric rain action. A grass-skirted native girl entertains a village of island residents, where a beach boy sits admiting virtially everything except the swaying hands, but barely has enough energy to stand, only doing so by clutching to the trunk of a palm tree. After completing her dance, the girl tosses a flower lei flirtatiously around the neck of the boy, then runs to a diving board at a nearby waterfall for a swim. The boy attempts to follow, huffing and puffing. The girl performs a graceful dive, into a pool hundreds of feet below. In a gag accomplished with 2D animation cels seen below a shallow overlaid transparent tray of surface water, she swims below the water surface, her grass skirt raising at every forward stroke to reveal her very-bare rear end! (How did Paramount get a release certificate for this scene?) Some curious and lecherous natives from another tribe spot her visible charms, and decide she would make the perfect sacrifice to the volcano. The girl is kidnaped, although the boy challenges “Over my dead body”. The natives nearly oblige him, by blowing him down, then walking right over him as they exit, one cleaning his feet by scraping them along the side of the boy’s ear.

The film receives a brief honorable mention here for a little atmospheric rain action. A grass-skirted native girl entertains a village of island residents, where a beach boy sits admiting virtially everything except the swaying hands, but barely has enough energy to stand, only doing so by clutching to the trunk of a palm tree. After completing her dance, the girl tosses a flower lei flirtatiously around the neck of the boy, then runs to a diving board at a nearby waterfall for a swim. The boy attempts to follow, huffing and puffing. The girl performs a graceful dive, into a pool hundreds of feet below. In a gag accomplished with 2D animation cels seen below a shallow overlaid transparent tray of surface water, she swims below the water surface, her grass skirt raising at every forward stroke to reveal her very-bare rear end! (How did Paramount get a release certificate for this scene?) Some curious and lecherous natives from another tribe spot her visible charms, and decide she would make the perfect sacrifice to the volcano. The girl is kidnaped, although the boy challenges “Over my dead body”. The natives nearly oblige him, by blowing him down, then walking right over him as they exit, one cleaning his feet by scraping them along the side of the boy’s ear.

Along comes a great white explorer and physician, in a canopied canoe rowed by about ten native bearers. He pushes the censorship envelope again, by commenting in song that in this land, “All the clothing that a lady needs, is some blades of grass and a string of beads.” He finds the boy prone in the sand, and hearing his tale of having no energy, prescribes Horlick’s. In 6 weeks (gee, it takes this long for the other natives to get around to arranging the volcano sacrifice?), he is a new man, swimming up waterfalls, swinging on vines like Tarzan, and uttering the Lord of the Jungle’s victory cry. He finally decides to scale the mountain in search of the natives’ sacrificial ceremony. As he climbs in bold strides, the skies around him turn black. He confronts the natives in battle, as lightning begins to flash behind him, and first drops of rain begin to hit. He knocks two natives backwards into the volcano crater, and they emerge in transparent 2-D cel form, floating up to heaven with angel wings (what, no devil pitchforks?), one moaning and rubbing his charred rear end. The boy faces off against the witch doctor, while a spear-head of the doctor bearing a face of its own provides blow-by-blow description of the bout like a radio announcer. The boy almost disappears into the crater himself, but miraculously flies out of it again to continue the fight. A final blow knocks the wooden head of the puppet doctor off his neck, as both head and body fall into the volcano, emerging as a 2-D angel segmented into two parts. The boy rubs noses with the girl tied to a stake, and releases her, and they stand together at the summit, watching a fading island sunset, for the fade out.

Along comes a great white explorer and physician, in a canopied canoe rowed by about ten native bearers. He pushes the censorship envelope again, by commenting in song that in this land, “All the clothing that a lady needs, is some blades of grass and a string of beads.” He finds the boy prone in the sand, and hearing his tale of having no energy, prescribes Horlick’s. In 6 weeks (gee, it takes this long for the other natives to get around to arranging the volcano sacrifice?), he is a new man, swimming up waterfalls, swinging on vines like Tarzan, and uttering the Lord of the Jungle’s victory cry. He finally decides to scale the mountain in search of the natives’ sacrificial ceremony. As he climbs in bold strides, the skies around him turn black. He confronts the natives in battle, as lightning begins to flash behind him, and first drops of rain begin to hit. He knocks two natives backwards into the volcano crater, and they emerge in transparent 2-D cel form, floating up to heaven with angel wings (what, no devil pitchforks?), one moaning and rubbing his charred rear end. The boy faces off against the witch doctor, while a spear-head of the doctor bearing a face of its own provides blow-by-blow description of the bout like a radio announcer. The boy almost disappears into the crater himself, but miraculously flies out of it again to continue the fight. A final blow knocks the wooden head of the puppet doctor off his neck, as both head and body fall into the volcano, emerging as a 2-D angel segmented into two parts. The boy rubs noses with the girl tied to a stake, and releases her, and they stand together at the summit, watching a fading island sunset, for the fade out.

Little Cesario (MGM, 8/30/41 – Bob Allen, dir.) – The title character is the littlest of a group of St. Bernard rescue dogs, stationed in a mountain monastery in the Alps. He is dim-witted, entirely inexperienced in rescuing, but with a determined heart to make a success of himself – and a hero-worshipper of Big Alexander, the chief dog of the rescue squad, with the most saved lives to his credit. Unfortunately, the admiration is nowhere close to equal in the opposite direction, and Alexander at best classifies Cesario as a meddling pest. Cesario spends the day botching one task after another, beginning with punching a combination time clock and brandy barrel dispenser, that he somehow causes to malfunction, dumping all the brandy barrels out upon him at once in an intoxicating mess. He gets totally underfoot of Alexander, following tracks beneath the larger dog’s belly. Then a storm hits. Blasts of icy wind strike the dogs between the eyes. Alexander remains steadfast in his task, bracing himself against the cold, and trudging determinedly on into the snow. Cesario, at the first chill, does exactly the opposite – racing back into the safety of the warm monastery. He looks out the window, continuing in his admiration of Alexander, and facing the realization that he will never be his equal, being by nature a hesitant coward. However, a sight through the window makes Cesario freeze – literally, into a dog of solid ice. Alexander has followed a trail out to the edge of a ledge ending in a straight drop into a deep canyon. An avalanche begins above Alexander’s head, and a shower of rocks falls just behind Alexander, taking out a large slab of trail behind him, and leaving the dog stranded atop a small pinnacle of rock, with no path forward or back.

Little Cesario (MGM, 8/30/41 – Bob Allen, dir.) – The title character is the littlest of a group of St. Bernard rescue dogs, stationed in a mountain monastery in the Alps. He is dim-witted, entirely inexperienced in rescuing, but with a determined heart to make a success of himself – and a hero-worshipper of Big Alexander, the chief dog of the rescue squad, with the most saved lives to his credit. Unfortunately, the admiration is nowhere close to equal in the opposite direction, and Alexander at best classifies Cesario as a meddling pest. Cesario spends the day botching one task after another, beginning with punching a combination time clock and brandy barrel dispenser, that he somehow causes to malfunction, dumping all the brandy barrels out upon him at once in an intoxicating mess. He gets totally underfoot of Alexander, following tracks beneath the larger dog’s belly. Then a storm hits. Blasts of icy wind strike the dogs between the eyes. Alexander remains steadfast in his task, bracing himself against the cold, and trudging determinedly on into the snow. Cesario, at the first chill, does exactly the opposite – racing back into the safety of the warm monastery. He looks out the window, continuing in his admiration of Alexander, and facing the realization that he will never be his equal, being by nature a hesitant coward. However, a sight through the window makes Cesario freeze – literally, into a dog of solid ice. Alexander has followed a trail out to the edge of a ledge ending in a straight drop into a deep canyon. An avalanche begins above Alexander’s head, and a shower of rocks falls just behind Alexander, taking out a large slab of trail behind him, and leaving the dog stranded atop a small pinnacle of rock, with no path forward or back.

Alexander looks up, to find the avalanche is far from through, with the largest boulder quivering directly above his head, about to dislodge from the mountainside. With appropriate sound effect, something inside Cesario “snaps”, and he charges forward to come to the aid of his hero. He finds one uncracked brandy barrel in the debris under the time clock, and attempts to barrel-roll it out the monastery door. But the door shuts before he can exit, cracking the barrel. Brandy or no brandy, Cesario charges the door, determined to butt it down to get outside. On cue, the wind blows the door open, causing Cesario to miss his target, and slide down the slippery ice of the pathway to the monastery. He sails over a cliff ledge, and drops many feet to a slope below. He begins rolling, and is quickly transformed into an ever-growing snowball. The ball reaches another slightly-elevated cliff edge, and makes a soaring jump across the canyon – scoring a direct hit upon Alexander on his precarious perch. Alexander is knocked away, becoming consumed inside the snowball as it passes, and lands upon the opposite side of the canyon – just as the boulder above gives way, smashing and destroying the place where Alexander had just stood.

Alexander looks up, to find the avalanche is far from through, with the largest boulder quivering directly above his head, about to dislodge from the mountainside. With appropriate sound effect, something inside Cesario “snaps”, and he charges forward to come to the aid of his hero. He finds one uncracked brandy barrel in the debris under the time clock, and attempts to barrel-roll it out the monastery door. But the door shuts before he can exit, cracking the barrel. Brandy or no brandy, Cesario charges the door, determined to butt it down to get outside. On cue, the wind blows the door open, causing Cesario to miss his target, and slide down the slippery ice of the pathway to the monastery. He sails over a cliff ledge, and drops many feet to a slope below. He begins rolling, and is quickly transformed into an ever-growing snowball. The ball reaches another slightly-elevated cliff edge, and makes a soaring jump across the canyon – scoring a direct hit upon Alexander on his precarious perch. Alexander is knocked away, becoming consumed inside the snowball as it passes, and lands upon the opposite side of the canyon – just as the boulder above gives way, smashing and destroying the place where Alexander had just stood.

Alexander is transported by the snowball to safety, but as the snow hits a rocky wall and smashes apart, Cesario is found in the shattered snow with a fractured paw. Grateful Alexander transports him home, and Cesario is next seen in a comfortable bed, his paw in a sling to heal, and surrounded by several of Alexander’s medals and trophies, which Alexander has bestowed upon Cesario for the feat of saving his life. Cesario has joined the ranks of the best of them, and Alexander gives Cesario an affectionate slurping kiss as the film closes. Cesario and Alexander are now a mutual admiration society.

Robinson Crusoe, Jr. (Warner, Porky Pig, 10/11/41 – Norman McCabe, dir.), receives a brief honorable mention. Porky Pig sets sail from the docks, but when the call goes out, “All ashore that’s going ashore”, a flock of rats make a hasty exit down the gangplank. One rat and his daughter (voiced by impressions of Fannie Brice as Baby Snooks and her “daddy” Hanley Stafford) are the last to leave, “daddy” insisting they get out immediately because he knows something about the boat – “Confidentially, it sinks.” Porky scoffs at the skeptical rats, displating a Guarantee certificate provided by the ship’s builder, guaranteeing the craft to be unsinkable. Then Porky has a thought. “I w-wonder if that goes for hurricanes?” Nature soon provides an answer, as the sky instantly darkens, and lightning bolts flash across the deck. Within a matter of seconds, the scene dissolves to the beach of an uncharted island, where Porky lays in the remaining planks that once were his ship. “I had to open my b-big mouth”, he mutters. The remainder of the film consists of an instant meeting with Friday (who waits on the beach with a welcome sign, asking, “Hello, Boss, What kept ya’?”), a musical example of their home life (set to a production number of then current Ink Spots hit, “Java Jive”), spot gags on animal life, and finally an encounter with cannibals (which Porky and Friday escape by carving a motorboat out of a tree, and hanging a plaque of an American flag on its stern, so that the native’s spears refuse to hit it).

Robinson Crusoe, Jr. (Warner, Porky Pig, 10/11/41 – Norman McCabe, dir.), receives a brief honorable mention. Porky Pig sets sail from the docks, but when the call goes out, “All ashore that’s going ashore”, a flock of rats make a hasty exit down the gangplank. One rat and his daughter (voiced by impressions of Fannie Brice as Baby Snooks and her “daddy” Hanley Stafford) are the last to leave, “daddy” insisting they get out immediately because he knows something about the boat – “Confidentially, it sinks.” Porky scoffs at the skeptical rats, displating a Guarantee certificate provided by the ship’s builder, guaranteeing the craft to be unsinkable. Then Porky has a thought. “I w-wonder if that goes for hurricanes?” Nature soon provides an answer, as the sky instantly darkens, and lightning bolts flash across the deck. Within a matter of seconds, the scene dissolves to the beach of an uncharted island, where Porky lays in the remaining planks that once were his ship. “I had to open my b-big mouth”, he mutters. The remainder of the film consists of an instant meeting with Friday (who waits on the beach with a welcome sign, asking, “Hello, Boss, What kept ya’?”), a musical example of their home life (set to a production number of then current Ink Spots hit, “Java Jive”), spot gags on animal life, and finally an encounter with cannibals (which Porky and Friday escape by carving a motorboat out of a tree, and hanging a plaque of an American flag on its stern, so that the native’s spears refuse to hit it).

The Great Cheese Mystery (Columbia/Screen Gems, Fable, 10/27/41 – Art Davis, dir., Frank Tashlin, supervision and writer (as “Tish Tash”). A little forgotten gem receives honorable mention. Tashlin and Warner fans may experience a degree of deja-vu, as one is instantly reminded of another Tashlin production for which this film almost seems the dress rehearsal – “A Tale of Two Mice”. Here, however, the mice roles are portrayed by a generic big and little mouse, rather that the Abbott and Costello doppelgangers Tash would eventually use in the Warner production. With the added familiar assist of Mel Blanc for voice characterization, it’s nearly an all-Warner-style get together, as the scene is set by driving rain and atmospheric thunder and lightning, first outside, then in interior scenes of a house, closing n on a mousehole in the basement baseboards. The shadows of two mice are seen on a brick wall inside the hole, as the larger of the two mice advises that everything’s set. The owners of the house are out, and the cat’s asleep. Nothing between them and the cheese in the kitchen. “Except…” The mouse’s dissertation is interrupted by what almost becomes a sneeze by his smaller partner, stopped by placing a finger underneath his nose. “…your hay fever”, the larger mouse concludes.

The Great Cheese Mystery (Columbia/Screen Gems, Fable, 10/27/41 – Art Davis, dir., Frank Tashlin, supervision and writer (as “Tish Tash”). A little forgotten gem receives honorable mention. Tashlin and Warner fans may experience a degree of deja-vu, as one is instantly reminded of another Tashlin production for which this film almost seems the dress rehearsal – “A Tale of Two Mice”. Here, however, the mice roles are portrayed by a generic big and little mouse, rather that the Abbott and Costello doppelgangers Tash would eventually use in the Warner production. With the added familiar assist of Mel Blanc for voice characterization, it’s nearly an all-Warner-style get together, as the scene is set by driving rain and atmospheric thunder and lightning, first outside, then in interior scenes of a house, closing n on a mousehole in the basement baseboards. The shadows of two mice are seen on a brick wall inside the hole, as the larger of the two mice advises that everything’s set. The owners of the house are out, and the cat’s asleep. Nothing between them and the cheese in the kitchen. “Except…” The mouse’s dissertation is interrupted by what almost becomes a sneeze by his smaller partner, stopped by placing a finger underneath his nose. “…your hay fever”, the larger mouse concludes.

A silent shot of the darkened kitchen, with the cat curled up in sleep in front of the refrigerator, is seen, as the camera pans slowly to a door at the kitchen entrance. It begins to open ever so slowly. The hinge begins to creak – until the hand of one of the mice appears in the twinkling of a eye, holding an oil can, and squirts the hinge until it stops creaking. The large mouse leads their entrance, followed by the small mouse, laden down with a full load of equipment to accomplish the caper. But he begins to sneeze again. The large mouse zooms back, tossing away into the air object after object of the equipment in order to reach the mouse’s nose in time. After preventing the sneeze, the large mouse rears back to give the little one a blow in the nose, but the smaller mouse points upward at a more immediate concern. The equipment is beginning to fall back to the floor, and if it hits will cause a clatter. The large mouse scampers about everywhere, caching object after object before impact, then finally collapses unser the burden after the last object is caught. The smaller mouse comes over to find him under the pile, knocking for him upon a wooden object as if upon a door. The large mouse’s arm emerges from the pile, and delivers a retaliatory twang to the small mouse’s nose.

A silent shot of the darkened kitchen, with the cat curled up in sleep in front of the refrigerator, is seen, as the camera pans slowly to a door at the kitchen entrance. It begins to open ever so slowly. The hinge begins to creak – until the hand of one of the mice appears in the twinkling of a eye, holding an oil can, and squirts the hinge until it stops creaking. The large mouse leads their entrance, followed by the small mouse, laden down with a full load of equipment to accomplish the caper. But he begins to sneeze again. The large mouse zooms back, tossing away into the air object after object of the equipment in order to reach the mouse’s nose in time. After preventing the sneeze, the large mouse rears back to give the little one a blow in the nose, but the smaller mouse points upward at a more immediate concern. The equipment is beginning to fall back to the floor, and if it hits will cause a clatter. The large mouse scampers about everywhere, caching object after object before impact, then finally collapses unser the burden after the last object is caught. The smaller mouse comes over to find him under the pile, knocking for him upon a wooden object as if upon a door. The large mouse’s arm emerges from the pile, and delivers a retaliatory twang to the small mouse’s nose.

After a blackout, the large mouse is seen carrying the load of equipment, while the small mouse follows – with one notable difference. Now, a large bandage is tied around his nose, in another attempt to prevent further sneezing. In a setup which would be seen again in “Tale of Two Mice”, the mice erect a scaffold and rope pulley, to hoist one of their partnership up to the level of the higher shelves within the refrigerator, where presumably the choicest food is stored. The smaller mouse tugs at the pulley rope from a ground-level position, while the larger mouse rises upward upon the scaffold, almost to the top. Suddenly, bandage or no bandage, another sneeze begins to come on. The large mouse zooms down the rope to place finger under nose again. The relieved smaller mouse relaxes, but forgets to hold onto the rope. The larger mouse is pulled upwards by the rope, as the scaffold zooms down. The mouse gets caught in the pulley, his torso wrapping entirely around the wheel. The scaffold (as in “Tale of Two Mice” comes to a stop, swaying a fraction of an inch above the cat’s sleeping head.

Let’s try that again, but with roles reversed. Now, the small mouse takes the ride, up the

Let’s try that again, but with roles reversed. Now, the small mouse takes the ride, up the

scaffold, carrying a drill and some miniature sticks of dynamite. He drills a hole in the refrigerator door, and inserts a lit TNT stick. Meanwhile, the larger mouse stuffs cotton into the ears of the cat to muffle the upcoming explosion. The cotton doesn’t work quite as expected, and the cat is mildly aroused. Pulling out one of the earplugs, the large mouse sings the cat a hasty lullaby, lulling the feline off to dreamland again. The small mouse peers into the blasted hole with a flashlight, locating an appealing hunk of Swiss cheese. He lifts the cheese above him, and begins to slowly carry it back towards the hole – failing to notice a small gap between the edge of the refrigerator shelf and the door hole. From a view of the kitchen exterior, we follow downwards an amalgam of sound effects that sounds like a pinball machine tallying up a mammoth score, as the little mouse plunges down shelf after shelf to the base of the refrigerator interior. The cat is aroused again, but the big mouse covers, appearing on the sill of an open window, and using various kitchen items and bric-a-brac to put on a sound-effects show of his own behind the window curtain. The cat is fooled into thinking the racket was from the storm outside, and falls back to sleep again, while the big mouse’s tongue hangs out from exhaustion.

With the cheese now finally out the door hole comes the job of getting it down. The big mouse lets out the rope little by little to lower the scaffold back to the ground. But he does not properly calculate the effect of the extra weight of the cheese, which upsets the balance of a small stick to which the rope pulley is attached, the stick only being supported by a pile of plates stacked upon the top of the refrigerator as a counterbalance to the scaffold and pulley. The dishes give way, toppling stick, scaffold, pulley, mouse and cheese to the ground, right on top of the cat. Looking out from the debris, the cat sees the hole in the refrigerator above him, and peers all around the room, looking for the culprits. He paces around in circles, changing his vantage point for a thorough search. What he doesn’t notice os that the two mice have taken positions inside the Swiss cheese, their legs protruding out the holes, so that they mimic the cat’s every move, staying eclipsed from his view beneath the cat’s belly. The cat finally pauses, but the foolish mice keep on walking – into his direct view. The jig is up, and the chase is on. In typical Tashlin love of unusual camera angles, the chase is followed without being directly seen, through exterior shots of the house and sound effects. Pauses in the action occur at the front door (where wooden panels are broken outwards from an interior impact), at an attic fireplace (where a brick chimney outside is shattered, revealing only a square trail of smoke clouds rising from what once was the chimney’s interior), and at a gabled attic window, the gable pushed outwards about four feet, and the window frame shattered). A repeated pounding sound descending toward the basement is revealed by an interior shot to signal the cat falling down the basement stairs. The mice finally make it to their mousehole, as the cat slams his head into the baseboard. Inside, the mice climb out of the cheese, and the little one begins to develop another sneeze. The large mouse instinctively bends to attempt to stop the ker-choo, but then thinks better of it, and begins laughing. The cheese is safely inside, and the cat is stuck outside, so what is there to lose? “Go on and sneeze. Blow your head off.” The little mouse finally gets to let one loose – and nobody guessed its power. With one blow, the entire cheese wedge is blasted across the mice’s apartment, and right out the mousehole, back to the cat. What is there left to do? Give the little mouse another painful twang in the nose, for the iris out.

With the cheese now finally out the door hole comes the job of getting it down. The big mouse lets out the rope little by little to lower the scaffold back to the ground. But he does not properly calculate the effect of the extra weight of the cheese, which upsets the balance of a small stick to which the rope pulley is attached, the stick only being supported by a pile of plates stacked upon the top of the refrigerator as a counterbalance to the scaffold and pulley. The dishes give way, toppling stick, scaffold, pulley, mouse and cheese to the ground, right on top of the cat. Looking out from the debris, the cat sees the hole in the refrigerator above him, and peers all around the room, looking for the culprits. He paces around in circles, changing his vantage point for a thorough search. What he doesn’t notice os that the two mice have taken positions inside the Swiss cheese, their legs protruding out the holes, so that they mimic the cat’s every move, staying eclipsed from his view beneath the cat’s belly. The cat finally pauses, but the foolish mice keep on walking – into his direct view. The jig is up, and the chase is on. In typical Tashlin love of unusual camera angles, the chase is followed without being directly seen, through exterior shots of the house and sound effects. Pauses in the action occur at the front door (where wooden panels are broken outwards from an interior impact), at an attic fireplace (where a brick chimney outside is shattered, revealing only a square trail of smoke clouds rising from what once was the chimney’s interior), and at a gabled attic window, the gable pushed outwards about four feet, and the window frame shattered). A repeated pounding sound descending toward the basement is revealed by an interior shot to signal the cat falling down the basement stairs. The mice finally make it to their mousehole, as the cat slams his head into the baseboard. Inside, the mice climb out of the cheese, and the little one begins to develop another sneeze. The large mouse instinctively bends to attempt to stop the ker-choo, but then thinks better of it, and begins laughing. The cheese is safely inside, and the cat is stuck outside, so what is there to lose? “Go on and sneeze. Blow your head off.” The little mouse finally gets to let one loose – and nobody guessed its power. With one blow, the entire cheese wedge is blasted across the mice’s apartment, and right out the mousehole, back to the cat. What is there left to do? Give the little mouse another painful twang in the nose, for the iris out.

Dumbo (Disney/RKO, 10/23/41) – Disney’s fourth fully-animated feature runs a bit shy on running time and on effects animation, resulting from shortages of labor from an animator’s strike, as well as a probable wish to turn a profit as opposed to immediately-preceding projects that ran over budget and lost money on their initial release. Its effects work was largely concentrated into two sequences. Prefacing the opening number, “Look Out For Mr. Stork”, narrator John McLeish recites the stork’s oath, similar in nature to that of a postman, completing his mission “Through the snow and sleet and hail, through the blizzard, through the gale…through the blinding lightning flash, and the mighty thunder crash…” These weather conditions are briefly depicted against a dark, cloud-filled night sky, until a clearing of the clouds reveals a precision squadron of storks flying in formation, each with a bundle bound for the Florida winter quarters of the circus (where Dumbo is eventually delivered, though a bit delayed in the stork’s arrival, due to the excess weight of his bundle). The second sequence, more extensive and feature-worthy in artistic content, is built around the work chant, “Song of the Roustabouts”. A railroad car full of dark, shadowy figures emerges from the Casey Jr. circus train as it arrives in the small town where the next performance will occur, just as the first drops of an oncoming rainstorm begin to fall. With dramatic impact, the roustabouts perform before our eyes the heavy labor of erecting the big top in a single evening. This aspect of circus life was never explored with this depth and believability in any other animated film (though approached to a degree in live-action in at least Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Greatest Show on Earth”). Notably imaginative is the use by the roustabouts of the help of some of the circus animals with their tasks, including enlisting the elephants for heavy hauling by rope and pulley, transportation of the canvas of the big top, and hammering at stakes, while a camel is used to transport tent poles between his humps. The roustabouts may likely be intended to be depicted as black, though the shadowy presentation of their efforts leaves uncertain their ethnicity. However, they are portrayed in the song’s lyrics in unflattering terms, admitting that they “Never learned to read or write”, and when they get their pay, “throw our pay away”. However, they describe themselves as nevertheless happy-hearted in spite of their hard work and hard luck – an image also possibly consistent with black stereotypes of the day. Because of the inability to definitively determine the race of the workers in the darkness, Disney has never seen need to edit the sequence (excepting possibly for time in early truncated hour-long broadcasts), which at least over the years has contributed to the naturalness and continuity of the film’s presentation. All the while as the sequence progresses, the storm action sets a moody background in detailed and realistic form, with wind whipping at the tent canvas, and lightning punctuating the song’s driving rhythm, until the last tugs of rope finally bring the big top canvas into position, and a few peaceful notes accompany a clear morning sky at crack of dawn, with the tent ready for business and decorative pennants gently flapping in the breeze from its poles.

Dumbo (Disney/RKO, 10/23/41) – Disney’s fourth fully-animated feature runs a bit shy on running time and on effects animation, resulting from shortages of labor from an animator’s strike, as well as a probable wish to turn a profit as opposed to immediately-preceding projects that ran over budget and lost money on their initial release. Its effects work was largely concentrated into two sequences. Prefacing the opening number, “Look Out For Mr. Stork”, narrator John McLeish recites the stork’s oath, similar in nature to that of a postman, completing his mission “Through the snow and sleet and hail, through the blizzard, through the gale…through the blinding lightning flash, and the mighty thunder crash…” These weather conditions are briefly depicted against a dark, cloud-filled night sky, until a clearing of the clouds reveals a precision squadron of storks flying in formation, each with a bundle bound for the Florida winter quarters of the circus (where Dumbo is eventually delivered, though a bit delayed in the stork’s arrival, due to the excess weight of his bundle). The second sequence, more extensive and feature-worthy in artistic content, is built around the work chant, “Song of the Roustabouts”. A railroad car full of dark, shadowy figures emerges from the Casey Jr. circus train as it arrives in the small town where the next performance will occur, just as the first drops of an oncoming rainstorm begin to fall. With dramatic impact, the roustabouts perform before our eyes the heavy labor of erecting the big top in a single evening. This aspect of circus life was never explored with this depth and believability in any other animated film (though approached to a degree in live-action in at least Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Greatest Show on Earth”). Notably imaginative is the use by the roustabouts of the help of some of the circus animals with their tasks, including enlisting the elephants for heavy hauling by rope and pulley, transportation of the canvas of the big top, and hammering at stakes, while a camel is used to transport tent poles between his humps. The roustabouts may likely be intended to be depicted as black, though the shadowy presentation of their efforts leaves uncertain their ethnicity. However, they are portrayed in the song’s lyrics in unflattering terms, admitting that they “Never learned to read or write”, and when they get their pay, “throw our pay away”. However, they describe themselves as nevertheless happy-hearted in spite of their hard work and hard luck – an image also possibly consistent with black stereotypes of the day. Because of the inability to definitively determine the race of the workers in the darkness, Disney has never seen need to edit the sequence (excepting possibly for time in early truncated hour-long broadcasts), which at least over the years has contributed to the naturalness and continuity of the film’s presentation. All the while as the sequence progresses, the storm action sets a moody background in detailed and realistic form, with wind whipping at the tent canvas, and lightning punctuating the song’s driving rhythm, until the last tugs of rope finally bring the big top canvas into position, and a few peaceful notes accompany a clear morning sky at crack of dawn, with the tent ready for business and decorative pennants gently flapping in the breeze from its poles.

The Cagey Canary (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 11/22/41- Fred (Tex) Avery/Robert Clampett (finishing up when Avery left the studio), dir.) – A veritable prototype for the standard serup that would become the eventual specialty of Tweety and Sylvester – and further somewhat predicting the setup for a Tom and Jerry or two later in the decade, such as “The Bodyguard” and “Quiet, Please”. Cat chases canary, but is reprimanded by an old crone, who threatens to throw the cat out into the rain unless he behaves, and tells the bird that if she is needed, just whistle. Various gags are spun off of the cat trying to keep the bird from whistling while accomplishing his goal. The “salted crackers” gag returns from its prior use by Avery for the whistling sentry mouse in “Ain’t We Got Fun”. A delightful gag of trapping the bird between an inverted glass and the palm of the cat’s paw results in the bird producing a large pin from nowhere, and sticking the cat’s paw with it, leaving him screaming and the bird free to whistle. (This gag would be lifted verbatim by Friz Freling in the Academy Award winner, “Tweetie Pie”.) Another Avery gag that would be revisited has the bird showing the cat a provocative pin-up poster, inducing from him a loud, reflexive wolf-whistle. (Avery would repeat this gag with additional twists in MGM’s “Rock-a-Bye Bear.”) Finally, the cat places a pair of earmuffs upon the sleeping crone, then lets the canary whistle all he wants – with no result. The bird turns up the decibel level, by activating a whistling tea kettle, an alarm clock, a cuckoo clock, and a radio. (These same four items were used for the same effect in a nearly identical setup to arouse Granny on Mel Blanc’s Capitol Records release, “Tweetie Pie” in the later 1940’s.) Here, even the added noise has no effect, and the characters chase through nearly every room of the house (including a bathroom which depicts no toilet) – all except the master bedroom. There, to his shock, the cat finds the bird standing confidently in the doorway, holding up the earmuffs which he has removed from the crone’s head. The cat doesn’t wait around for the repercussions, but exits through the front door, without opening it. The canary tosses the earmuffs away, but fails to note the impatient tapping toes of the crone, who has now been disturbed from her slumber. The bird takes one look upwards, and makes his own hasty retreat out and through the door panel. The final shots show the bird and cat, huddled together inside the cover of an old toppled barrel, with the rain falling all around them. They look back at the door of the house, where the light from within suddenly disappears from their door silhouettes, as the crone pulls a windowshade down to block any path of re-entry. Exchanging hopeless looks of sympathy between one another, the cat faces the audience, while the bird speaks his only line of dialogue as spokesperson for the two of them: “Ladies and gentlemen, would any of you in the audience be interested in a homeless cat and canary?”

The Cagey Canary (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 11/22/41- Fred (Tex) Avery/Robert Clampett (finishing up when Avery left the studio), dir.) – A veritable prototype for the standard serup that would become the eventual specialty of Tweety and Sylvester – and further somewhat predicting the setup for a Tom and Jerry or two later in the decade, such as “The Bodyguard” and “Quiet, Please”. Cat chases canary, but is reprimanded by an old crone, who threatens to throw the cat out into the rain unless he behaves, and tells the bird that if she is needed, just whistle. Various gags are spun off of the cat trying to keep the bird from whistling while accomplishing his goal. The “salted crackers” gag returns from its prior use by Avery for the whistling sentry mouse in “Ain’t We Got Fun”. A delightful gag of trapping the bird between an inverted glass and the palm of the cat’s paw results in the bird producing a large pin from nowhere, and sticking the cat’s paw with it, leaving him screaming and the bird free to whistle. (This gag would be lifted verbatim by Friz Freling in the Academy Award winner, “Tweetie Pie”.) Another Avery gag that would be revisited has the bird showing the cat a provocative pin-up poster, inducing from him a loud, reflexive wolf-whistle. (Avery would repeat this gag with additional twists in MGM’s “Rock-a-Bye Bear.”) Finally, the cat places a pair of earmuffs upon the sleeping crone, then lets the canary whistle all he wants – with no result. The bird turns up the decibel level, by activating a whistling tea kettle, an alarm clock, a cuckoo clock, and a radio. (These same four items were used for the same effect in a nearly identical setup to arouse Granny on Mel Blanc’s Capitol Records release, “Tweetie Pie” in the later 1940’s.) Here, even the added noise has no effect, and the characters chase through nearly every room of the house (including a bathroom which depicts no toilet) – all except the master bedroom. There, to his shock, the cat finds the bird standing confidently in the doorway, holding up the earmuffs which he has removed from the crone’s head. The cat doesn’t wait around for the repercussions, but exits through the front door, without opening it. The canary tosses the earmuffs away, but fails to note the impatient tapping toes of the crone, who has now been disturbed from her slumber. The bird takes one look upwards, and makes his own hasty retreat out and through the door panel. The final shots show the bird and cat, huddled together inside the cover of an old toppled barrel, with the rain falling all around them. They look back at the door of the house, where the light from within suddenly disappears from their door silhouettes, as the crone pulls a windowshade down to block any path of re-entry. Exchanging hopeless looks of sympathy between one another, the cat faces the audience, while the bird speaks his only line of dialogue as spokesperson for the two of them: “Ladies and gentlemen, would any of you in the audience be interested in a homeless cat and canary?”

Pantry Panic (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 11/24/41 – Walter Lantz, dir.) – One of the first films reviewed back when these trail columns began on this site, accounting for the origin of an often-revisited animation trope: the “good guy” becoming a cannibal when exposed to extreme hunger. We’ll actually be briefly revisiting all three of Woody’s excursions into this sub-genre in the course of these current articles, as all three are motivated by drastic changes in the weather. Winter is drawing on, and Mr. Groundhog’s predictions of same have all of birdland scrambling for warmer climes. But Woody is too preoccupied with enjoying practicing swan dives off a diving board to join the exiting crowd. In mid-dive, winter hits – freezing him in an ice block in mid-air. He crashes onto the frozen pond, observing “Must be hard water in this place.” A stiff breeze blows him airborne, where two humanized clouds bat him around like a badminton bird, finally landing him in his home. An intertitle advises us of the passing of time: “The Next Day, and 130 degrees below zero. (Sounds authentic.)” Woody scoffs at the winds outside his shuttered windows and bolted door, while sitting at a table filled to overflowing with foodstuffs. “Blow your head off. See if I care. It’s nice and warm here, and I’ve got plenty of food.” Suddenly the front door blows open in spite of the latches, revealing a compact cyclone (maybe a cousin to Mickey’s “The Little Whirlwind”). It enters the house and proceeds to suck up all the food from the table, spin Woody around a few times, then make a hasty retreat over the horizon. A second intertitle now advises us it is two weeks later, and starvation is staring Woody in the face. We cut to just that – a twin to Dickens’ ghost of Christmas future sitting across the table from Woody. Starvation laughs a sinister laugh in Woody’s face – and Woody defiantly laughs right back at him in the same manner. The remainder of the cartoon pits Woody against “a poor hungry little kitty cat” (twice as tall as Woody, with a booming basso voice), who claims he’s so hungry he’ll eat anything – including a woodpecker. Woody is equally smitten with an instant appetite for “feline fricassee”, and the battle begins as to who will eat who. As discussed in my article of long ago, “Unhealthy Appetites”, the set-pieces and ideas of this cartoon still had a ways to go to develop and fine-tune themselves, awaiting the finer directorial hands of Tex Avery and James Culhane to rise to the level of high comedy in later films. The film ends with an unnerving and violent twist, as a wandering moose pokes his head in the door, disrupting entirely Woody’s and the cat’s fight among themselves, and causing the two of them to pursue the moose into the woods, knives raised and held in their hands. The scene wipes to a disturbing shot of a pile of skeletal bones – all that is left of the moose. Woody and the cat are polishing off the last bites from huge bones held in their hands. The cat announces, “That was pretty good. But I’m still hungry.” Woody, with the evilest glint in his eye, replies, “Yeah? So am I!” Both whip out their respective carving weapons, and the scene becomes a blur in a whirling knife fight, as we fade out to end credits. One of the most ghastly endings of any Hollywood cartoon.

Pantry Panic (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 11/24/41 – Walter Lantz, dir.) – One of the first films reviewed back when these trail columns began on this site, accounting for the origin of an often-revisited animation trope: the “good guy” becoming a cannibal when exposed to extreme hunger. We’ll actually be briefly revisiting all three of Woody’s excursions into this sub-genre in the course of these current articles, as all three are motivated by drastic changes in the weather. Winter is drawing on, and Mr. Groundhog’s predictions of same have all of birdland scrambling for warmer climes. But Woody is too preoccupied with enjoying practicing swan dives off a diving board to join the exiting crowd. In mid-dive, winter hits – freezing him in an ice block in mid-air. He crashes onto the frozen pond, observing “Must be hard water in this place.” A stiff breeze blows him airborne, where two humanized clouds bat him around like a badminton bird, finally landing him in his home. An intertitle advises us of the passing of time: “The Next Day, and 130 degrees below zero. (Sounds authentic.)” Woody scoffs at the winds outside his shuttered windows and bolted door, while sitting at a table filled to overflowing with foodstuffs. “Blow your head off. See if I care. It’s nice and warm here, and I’ve got plenty of food.” Suddenly the front door blows open in spite of the latches, revealing a compact cyclone (maybe a cousin to Mickey’s “The Little Whirlwind”). It enters the house and proceeds to suck up all the food from the table, spin Woody around a few times, then make a hasty retreat over the horizon. A second intertitle now advises us it is two weeks later, and starvation is staring Woody in the face. We cut to just that – a twin to Dickens’ ghost of Christmas future sitting across the table from Woody. Starvation laughs a sinister laugh in Woody’s face – and Woody defiantly laughs right back at him in the same manner. The remainder of the cartoon pits Woody against “a poor hungry little kitty cat” (twice as tall as Woody, with a booming basso voice), who claims he’s so hungry he’ll eat anything – including a woodpecker. Woody is equally smitten with an instant appetite for “feline fricassee”, and the battle begins as to who will eat who. As discussed in my article of long ago, “Unhealthy Appetites”, the set-pieces and ideas of this cartoon still had a ways to go to develop and fine-tune themselves, awaiting the finer directorial hands of Tex Avery and James Culhane to rise to the level of high comedy in later films. The film ends with an unnerving and violent twist, as a wandering moose pokes his head in the door, disrupting entirely Woody’s and the cat’s fight among themselves, and causing the two of them to pursue the moose into the woods, knives raised and held in their hands. The scene wipes to a disturbing shot of a pile of skeletal bones – all that is left of the moose. Woody and the cat are polishing off the last bites from huge bones held in their hands. The cat announces, “That was pretty good. But I’m still hungry.” Woody, with the evilest glint in his eye, replies, “Yeah? So am I!” Both whip out their respective carving weapons, and the scene becomes a blur in a whirling knife fight, as we fade out to end credits. One of the most ghastly endings of any Hollywood cartoon.

The Hungry Wolf (MGM, 2/21/42 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – Though far from a height of hilarity, this cartoon is lushly well-produced, and, though a little cloying in its portrayal of a gullible and unsuspecting young rabbit, reaches an almost psychological depth for a study in cartoon angst of a typical animated villain – a forest wolf – when the chips are down. Knowing the way of wolves, we receive no backstory as to how the wolf got to be who he is, but are only left to presume he has led the usual ravenous life of devouring smaller, helpless animals. Now, he finds himself alone, in the dead of winter and amidst the onset of a blizzard, in a cold cave home, in which the fire in the hearth has gone out, and in which lay only a pile of empty tin cans and a few basic items of furniture. His teeth chatter from the cold, as he bends over what he hopes might be the last live embers in the fireplace, but finds his paws turning blue. The cupboard is truly bare – right down to an entirely empty flour drawer – and all that remains inside its shelves is cobwebs. Hope briefly rises as the wolf spies a mousetrap, with a small piece of cheese. That small morsel of Swiss looks so appealing. But the wolf entirely forgets what a mousetrap is for – and takes it on the digits when the trap snaps. The cheese falls to the floor, where a mouse who looks loke a near twin to the early Jerry makes off with the fallen bait, into a knothole. The crazed wolf rips up a path of floorboards in his efforts to get at the rodent, then almost tears through the rock wall of his cave as the rodent escapes through a crack between the floor and the boulder wall. The wolf’s stomach bellows with emptiness, and the wolf tightens his belt in attempt to stifle it. He seats himself at the empty table, pounding upon it to vent his agony at trying to get through this crisis. He then spots a coil of rope hanging from a hook. Our first thought is that perhaps he is contemplating doing himself in. Instead, he envisions the rope as a long link of sausages. In his frenzy, he begins chomping on them – only to spit out the unpalatable rope fibers. Angrily, he tosses the rope coil through the glass of a window. However, looking outside after it, his crazed brain again converts the image to the imaginary sausage view. He tries to exit out the front door – but stormy winds drive him backwards, and blast away all the canvas off an umbrella he tries to hold out in front of him. The best the wolf is able to do is shut the door without exiting, not even remembering to latch it shut. He turns to glance back at the table, and reacts with wonderment at spotting a large, tasty-looking ear of corn upon it. He ravenously chews on the corn, only to pause, and find his mouth full of wooden splinters. He has been chewing on a rolling pin.

The Hungry Wolf (MGM, 2/21/42 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – Though far from a height of hilarity, this cartoon is lushly well-produced, and, though a little cloying in its portrayal of a gullible and unsuspecting young rabbit, reaches an almost psychological depth for a study in cartoon angst of a typical animated villain – a forest wolf – when the chips are down. Knowing the way of wolves, we receive no backstory as to how the wolf got to be who he is, but are only left to presume he has led the usual ravenous life of devouring smaller, helpless animals. Now, he finds himself alone, in the dead of winter and amidst the onset of a blizzard, in a cold cave home, in which the fire in the hearth has gone out, and in which lay only a pile of empty tin cans and a few basic items of furniture. His teeth chatter from the cold, as he bends over what he hopes might be the last live embers in the fireplace, but finds his paws turning blue. The cupboard is truly bare – right down to an entirely empty flour drawer – and all that remains inside its shelves is cobwebs. Hope briefly rises as the wolf spies a mousetrap, with a small piece of cheese. That small morsel of Swiss looks so appealing. But the wolf entirely forgets what a mousetrap is for – and takes it on the digits when the trap snaps. The cheese falls to the floor, where a mouse who looks loke a near twin to the early Jerry makes off with the fallen bait, into a knothole. The crazed wolf rips up a path of floorboards in his efforts to get at the rodent, then almost tears through the rock wall of his cave as the rodent escapes through a crack between the floor and the boulder wall. The wolf’s stomach bellows with emptiness, and the wolf tightens his belt in attempt to stifle it. He seats himself at the empty table, pounding upon it to vent his agony at trying to get through this crisis. He then spots a coil of rope hanging from a hook. Our first thought is that perhaps he is contemplating doing himself in. Instead, he envisions the rope as a long link of sausages. In his frenzy, he begins chomping on them – only to spit out the unpalatable rope fibers. Angrily, he tosses the rope coil through the glass of a window. However, looking outside after it, his crazed brain again converts the image to the imaginary sausage view. He tries to exit out the front door – but stormy winds drive him backwards, and blast away all the canvas off an umbrella he tries to hold out in front of him. The best the wolf is able to do is shut the door without exiting, not even remembering to latch it shut. He turns to glance back at the table, and reacts with wonderment at spotting a large, tasty-looking ear of corn upon it. He ravenously chews on the corn, only to pause, and find his mouth full of wooden splinters. He has been chewing on a rolling pin.

The door of the cave opens. Enter an overly cute, adorable little boy bunny who has lost his way in the storm, and seeks to come inside for a visit. He is too young to know of the wolf’s reputation, or to have any instinctive fear of him. Instead, he observes the wolf sympathetically, asking him if he feels well. As the wolf comes out of his daze, his eyes widen at the sight of the plump, tender rabbit. His curious hands reflexively reach out, to feel the rabbit’s fur and plush cheeks, making absolutely sure he is not just dreaming what he observes. The wolf replies that he never felt better in his life, as his mind’s eye envisions the bunny resting cooked upon a platter, surrounded by garnishing vegetables. But the bunny isn’t convinced of the wolf’s condition, as the wolf gives out with a loud sneeze from the cold. The rabbit undoes a warm scarf he is wearing, tying it around the wolf’s neck to keep him warm, then produces a match (‘cause he s a boy scout) to rekindle the fire in the hearth. The wolf’s growling tummy raises the bunny’s curiosity, almost giving the wolf’s intentions away, while the wolf diverts attention from himself by burying his face within the pages of a book – a cook book, describing recipies for frying or boiling rabbit. When the fire is going well, and ice in the wolf’s cooking pot thaws to simmering water, the wolf invites the rabbit to help him set the table for dinner, getting the rabbit into a festive spirit with some singing choruses of “Happy Days Are Here Again.” Just as the wolf lifts the bunny up, bringing him ever closer to dropping him into the pot, the bunny remarks that the wolf is so nice, he wishes he were the bunny’s daddy, adding that he has no daddy. The wolf’s heart begins to break, and he endures a psychological torture/crisis, his mind’s eye visions double-exposing between the boiling pot water, and the image of the bunny on a plate. Twising himself up in mental knots, the wolf reaches his wits’ end. His facade of kindness to win the rabbit’s confidence falls, and he shouts “Get OUT!” The rabbit innocently inquires. “What’s the matter? Don’t you like me?” “I HATE you!” snarls the wolf, and quickly ushers the rabbit outside, slamming the door behind him. The bunny is heartbroken, and begins to sniffle tears of disbelief at the wolf’s change of feeling toward him. With an unfailing attitude of charity, the rabbit calls through the door that the wolf can still keep the scarf, and slowly ventures forward into the snow, resigning himself to getting back to mother and searching for his own home. The agonized wolf again sits and stares hopelessly at the table, unforgiving of himself for letting the rabbit get away, and chastising himself, “I must be slipping.” He begins breathing heavily, and undergoes a transition of mood that can almost qualify as parallel to the transformation of Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde. The result is a ravenous, snarling beast, now beyond uttering conversational words, who stalks out into the blizzard with all the remaining power available to him, attempting to track down his prey. He follows the trail of small footprints deep into the woods, his steps sometimes slowing, nearly stumbling on occasion, but always regaining his fierceness and determination, and making his way ever closer to the position of the bunny, as they both round a rocky corner and disappear from camera view, the wolf only a few feet in arrears of his delicious quarry.

The door of the cave opens. Enter an overly cute, adorable little boy bunny who has lost his way in the storm, and seeks to come inside for a visit. He is too young to know of the wolf’s reputation, or to have any instinctive fear of him. Instead, he observes the wolf sympathetically, asking him if he feels well. As the wolf comes out of his daze, his eyes widen at the sight of the plump, tender rabbit. His curious hands reflexively reach out, to feel the rabbit’s fur and plush cheeks, making absolutely sure he is not just dreaming what he observes. The wolf replies that he never felt better in his life, as his mind’s eye envisions the bunny resting cooked upon a platter, surrounded by garnishing vegetables. But the bunny isn’t convinced of the wolf’s condition, as the wolf gives out with a loud sneeze from the cold. The rabbit undoes a warm scarf he is wearing, tying it around the wolf’s neck to keep him warm, then produces a match (‘cause he s a boy scout) to rekindle the fire in the hearth. The wolf’s growling tummy raises the bunny’s curiosity, almost giving the wolf’s intentions away, while the wolf diverts attention from himself by burying his face within the pages of a book – a cook book, describing recipies for frying or boiling rabbit. When the fire is going well, and ice in the wolf’s cooking pot thaws to simmering water, the wolf invites the rabbit to help him set the table for dinner, getting the rabbit into a festive spirit with some singing choruses of “Happy Days Are Here Again.” Just as the wolf lifts the bunny up, bringing him ever closer to dropping him into the pot, the bunny remarks that the wolf is so nice, he wishes he were the bunny’s daddy, adding that he has no daddy. The wolf’s heart begins to break, and he endures a psychological torture/crisis, his mind’s eye visions double-exposing between the boiling pot water, and the image of the bunny on a plate. Twising himself up in mental knots, the wolf reaches his wits’ end. His facade of kindness to win the rabbit’s confidence falls, and he shouts “Get OUT!” The rabbit innocently inquires. “What’s the matter? Don’t you like me?” “I HATE you!” snarls the wolf, and quickly ushers the rabbit outside, slamming the door behind him. The bunny is heartbroken, and begins to sniffle tears of disbelief at the wolf’s change of feeling toward him. With an unfailing attitude of charity, the rabbit calls through the door that the wolf can still keep the scarf, and slowly ventures forward into the snow, resigning himself to getting back to mother and searching for his own home. The agonized wolf again sits and stares hopelessly at the table, unforgiving of himself for letting the rabbit get away, and chastising himself, “I must be slipping.” He begins breathing heavily, and undergoes a transition of mood that can almost qualify as parallel to the transformation of Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde. The result is a ravenous, snarling beast, now beyond uttering conversational words, who stalks out into the blizzard with all the remaining power available to him, attempting to track down his prey. He follows the trail of small footprints deep into the woods, his steps sometimes slowing, nearly stumbling on occasion, but always regaining his fierceness and determination, and making his way ever closer to the position of the bunny, as they both round a rocky corner and disappear from camera view, the wolf only a few feet in arrears of his delicious quarry.

For the first time, we change view to the happy home of the rabbit family, where about a dozen small bunnies wait around the dinner table and occupy themselves with little games and parlor tricks, while one chair remains empty. Mother rabbit wipes frost off the window pane, peering out for her one errant son, then puts on a kerchief, exiting the hutch to search for where her boy can be. She picks up a trail of small footprints, then traces steps to the same rocky corner where we last saw her son and the wolf. As she rounds the corner, she utters a loud gasp, and we expect the worst. However, it is not what we thought. The bunny is there, in one piece and entirely safe from harm. The gasp was brought on by a different view – the wolf, nearly stiff as a board and lying on his back in the snow. “Guess he musta fainted”, explains the bunny. Mom and the bunny combine their strength to raise the wolf up out of the snow, and in the final sequence, we see the wolf’s feet submerged in a pail of soothing hot water from a kettle, and pan upwards to find the wolf awake and revived, and finally happy, as he is being fed his fill of roast turkey prepared by mother rabbit, in the warmth of the rabbits’ cozy hutch. His needs finally satisfied, the wolf joins between mouthfuls in the rabbits’ chorus of “Happy Days are Here Again”, for the iris out.

For the first time, we change view to the happy home of the rabbit family, where about a dozen small bunnies wait around the dinner table and occupy themselves with little games and parlor tricks, while one chair remains empty. Mother rabbit wipes frost off the window pane, peering out for her one errant son, then puts on a kerchief, exiting the hutch to search for where her boy can be. She picks up a trail of small footprints, then traces steps to the same rocky corner where we last saw her son and the wolf. As she rounds the corner, she utters a loud gasp, and we expect the worst. However, it is not what we thought. The bunny is there, in one piece and entirely safe from harm. The gasp was brought on by a different view – the wolf, nearly stiff as a board and lying on his back in the snow. “Guess he musta fainted”, explains the bunny. Mom and the bunny combine their strength to raise the wolf up out of the snow, and in the final sequence, we see the wolf’s feet submerged in a pail of soothing hot water from a kettle, and pan upwards to find the wolf awake and revived, and finally happy, as he is being fed his fill of roast turkey prepared by mother rabbit, in the warmth of the rabbits’ cozy hutch. His needs finally satisfied, the wolf joins between mouthfuls in the rabbits’ chorus of “Happy Days are Here Again”, for the iris out.

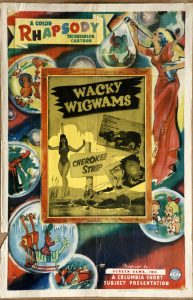

Wacky Wigwams (Columbia/Screen Gems. Color Rhapsody, 2/22/42 – Alec Geiss. dir., Frank Tashlin, supervision) – A far above-par outing for Screen Gems, virtually indistinguishable from many of the better Warner Brothers’ spot gag reels of Avery or Clampett. Full of action and play-on-words, the short follows various phases of Indian life. We first meet the chief. Frank Graham provides spirited narration, introducing us to Chief Thunder Cloud. Taking the name to its literal extreme, the Chief emerges from a tent – a barely-humanized anthropomorphic black cloud in walking form, replete with periodic white claps of thunder and lightning from within himself. The chief stands before us as the narrator asks him to say something to the audience. In a gag that was likely noticed by Tashlin’s old stablemate Chuck Jones for a memorable reworking in “Wackiki Wabbit”, the chief utters a single word by way of producing a small white puff of a cloud from his “mouth”, which we hear only as “Ugh”. The narrator freely translates: “Quote: The chief welcomes us and extends the hospitality of his people and hopes that we enjoy our sojourn in their midst. Unquote.” The chief then utters another, identical sounding “Ugh”. The narrator translates: “Period.”

Wacky Wigwams (Columbia/Screen Gems. Color Rhapsody, 2/22/42 – Alec Geiss. dir., Frank Tashlin, supervision) – A far above-par outing for Screen Gems, virtually indistinguishable from many of the better Warner Brothers’ spot gag reels of Avery or Clampett. Full of action and play-on-words, the short follows various phases of Indian life. We first meet the chief. Frank Graham provides spirited narration, introducing us to Chief Thunder Cloud. Taking the name to its literal extreme, the Chief emerges from a tent – a barely-humanized anthropomorphic black cloud in walking form, replete with periodic white claps of thunder and lightning from within himself. The chief stands before us as the narrator asks him to say something to the audience. In a gag that was likely noticed by Tashlin’s old stablemate Chuck Jones for a memorable reworking in “Wackiki Wabbit”, the chief utters a single word by way of producing a small white puff of a cloud from his “mouth”, which we hear only as “Ugh”. The narrator freely translates: “Quote: The chief welcomes us and extends the hospitality of his people and hopes that we enjoy our sojourn in their midst. Unquote.” The chief then utters another, identical sounding “Ugh”. The narrator translates: “Period.”

Many visual puns are nicely played upon throughout the cartoon, such as Indian reservations (waiting in a ticket line for front row seats), scalping (a reseller who offers us tickets on the 40 yard line), various tribes (Black-feet, Pawn-ee, and the Cleveland Indians), and a reference before Bob Clampett to the “Cherokee Strip”, definitely inspired by Tex Avery’s similar gag of “shedding skin” in “Cross-Country Detours”. As in Avery’s strip-tease, the key spots in the action (smoothly animated from live-reference footage – some sources claim Emery Hawkins heavily contributed to this film, though an animator breakdown is not yet known) are interrupted, not by a “Censored” sign, but by an old-fashioned magic lantern slide being projected on the screen, calling a Dr. Schmaltz to the box office. The narrator begs Schmaltz to report to the box office so we can return to the action, but too late, as only the bare arm and leg of the lovely Indian princess are left to be seen exiting the screen. “Dr Schmaltz! Phooey!” grumbles the narrator. (A freeze-frame viewing of the sequence just before the second entry of the lantern slide is in order, however, as the animators get away with murder for a single frame!) Another memorable gag shows us a Witch Doctor, posed with heavy shadow modeling over a glowing pot of an unknown brew, as the narrator asks in broken English what’s cookin’. The Doctor suddenly transforms in personality to a formal Englishman, and invites us to share in a “Spot of tea, old thing?” The film also climaxes with a lively and action-packed buffalo hunt.

But throughout the film, in the style of Avery, there is the inevitable running gag. A drought has hit the plains, causing the corn crop to pop off the stalks as popcorn. A medicine man is called upon (his teepee decked out like a drug store, with sign reading “Prescriptions filled”, and even a coin-operated gumball machine at the entrance for the kiddies). To make it rain, he begins to perform the ceremonial “Snake Dance”, transforming in his movements to the form of a serpent slithering on his belly, rattling his feet like a tail, and protruding his tongue. He slithers around and around in the sand as we temporarily leave him. When we return, still no rain, but a circular ditch has developed from his belly-friction upon the sand, leaving the medicine man nearly hidden in the furrow. The narrator comments that he’s really getting in the groove. When we return for the final scene, the ditch is twice as deep, and the tired medicine man struggles to climb out of the trench – but the terrain is still dry as a bone. Suddenly, the medicine man has a new idea. “Me got-um!”, he shouts. Producing a can of car polish, he hastens over to an old jalopy parked next to his teepee, and polishes it to a sparkling “new-car” shine. No sooner is the job completed, than the skies turn black, lightning flashes, and a downpour of rain falls upon the car and the countryside. The happy rainmaker breaks into hysterical laughter, as the narrator calmly remarks, “And the rains came. Has it ever happened to you?”

But throughout the film, in the style of Avery, there is the inevitable running gag. A drought has hit the plains, causing the corn crop to pop off the stalks as popcorn. A medicine man is called upon (his teepee decked out like a drug store, with sign reading “Prescriptions filled”, and even a coin-operated gumball machine at the entrance for the kiddies). To make it rain, he begins to perform the ceremonial “Snake Dance”, transforming in his movements to the form of a serpent slithering on his belly, rattling his feet like a tail, and protruding his tongue. He slithers around and around in the sand as we temporarily leave him. When we return, still no rain, but a circular ditch has developed from his belly-friction upon the sand, leaving the medicine man nearly hidden in the furrow. The narrator comments that he’s really getting in the groove. When we return for the final scene, the ditch is twice as deep, and the tired medicine man struggles to climb out of the trench – but the terrain is still dry as a bone. Suddenly, the medicine man has a new idea. “Me got-um!”, he shouts. Producing a can of car polish, he hastens over to an old jalopy parked next to his teepee, and polishes it to a sparkling “new-car” shine. No sooner is the job completed, than the skies turn black, lightning flashes, and a downpour of rain falls upon the car and the countryside. The happy rainmaker breaks into hysterical laughter, as the narrator calmly remarks, “And the rains came. Has it ever happened to you?”

The winds whip through more of ‘42, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Of this week’s two Hugh Harman cartoons, “Little Cesario” is annoyingly repetitive, but I found “The Hungry Wolf” quite enjoyable. I got at least one chuckle out of it when the young rabbit said: “I’ve got a match! I’m a Boy Scout!” It calls to mind a joke I remember from my own Boy Scout days: How do you make a fire with just two sticks? Make sure one of them is a match.

There really is a kind of tree called the Slippery elm, though unlike the one pictured in “Robinson Crusoe Jr.” it’s the inner, not the outer, bark that’s slippery. Nowadays it’s used in a lot of worthless quack medicines.

The debate over whether the roustabouts in “Dumbo” are meant to be African-American or not has been going on for a long time, and as conducted with the typical decorum and maturity of social media it generally goes like this: “They must be!” “They can’t be!” “Sez you!” “So’s your old man!” And so on. The bigger question is, was the job of circus roustabout customarily performed by African-Americans during the Jim Crow era? I honestly don’t know. One might assume so, but then I’ve seen a page of Help Wanted ads from a Florida newspaper circa 1950 in which the ones for fruit pickers — another unskilled, low-paid, outdoor occupation — specified “Whites only”. In any case, it’s a question that can at least be verified or refuted in principle, which would be far more fruitful than endless arguing about the colour of paint in a Disney picture.

Every time I see “Pantry Panic”, I have to watch the scene where the moose’s head slides down between his forelegs and comes out the other end frame by frame, over and over. It never ceases to crack me up and blow my mind.

Re “Pantry Panic,” I think the “starving person becomes cannibal” bit first shows up in Charlie Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush”(1925), where Charlie and Mack Swain are trapped in a cabin during a blizzard and run out of food. Swain is watching Charlie pace, and starts hallucinating Charlie as a giant chicken, and lunges at him.

Horlick’s malted milk was indeed sold (and made) in the US – the company sponsored the “Lum & Abner” radio show, a sponsorship that ended only after the company founder died (William Horlick was a fan of the show).

WACKY WIGWAMS is a truly funny short, and from SCREEN GEMS/COLUMBIA of all studios!!

This Color Rhapsody is a guilty pleasure of mine – funny spot gags, a great musical score (especially during the Buffalo hunt) and beautifully animated (some great Emery Hawkins animation as well!)

The Columbia Color Rhapsody released immediately prior to “Wacky Wigwams”, “A Hollywood Detour” (24/1/42 — Frank Tashlin, dir.), opens with rain pouring onto a map of the United States — all except for “sunny California”, which is the narrator’s cue to take the viewer on a tour of the glories of Hollywood. At the end, the narrator bids “farewell to Hollywood, where nothing is certain…. Except, of course, the sunshine.” Then there is a flash of lightning, and rain pours down on the movie colony for the iris out.

So Southern California is sunny, except when it rains. Cartoons have made this profound and hilarious observation before, and they’ll do it again.

“Confidentially, it sinks” (said by the daddy rat in “Robinson Crusoe, Jr.”) and “Confidentially, it shrinks” (said by the Indian weaver in “Wacky Wigwams”) come from the 1938 film “You Can’t Take It with You.” Ballet master Kolenkov says of one of his students, “Confidentially, she stinks.” The line, or a variation of it, is heard in several cartoons of the period.

With apologies, a title I overlooked from this period was “Tulips Shall Grow” (George Pal, Madcap Models, 1/26/42), which I didn’t realize was released so early in the war. George’s epic vision of the German invasion of Holland (accomplished in this film by the all-metal army of nuts (and bolts) known a the Screwballs) leaves a native of the land, fleeing the devastation of the battlefront, taking refuge in the bombed-out remains of an old church, and praying to the heavens for a miracle to rescue his land. Nature supplies the miracle, in the form of rain. The invading troops and general are quickly rusted solid, and the massive tanks roaming the land are unable to pop out their defensive umbrellas as the levers also rust solid. The last of the tanks, unable to proceed, sinks slowly and dramatically into a huge mud piddle, never to be seen again. Tulips, and the landscape in general, spring back to life, and the Hollander is reunited with his love, as clouds in the sky form into the shape of a Victory V.