It won’t help you to try to lay low until the heat’s off. Our 1930’s firehouse toons will steam up your glasses and light a hotfoot under your funny bone. So grab a chair (preferably of inflammable material), and make it your own personal “hot seat”, as a new round of red hots fresh off the griddle light up your eyes.

Fireman, Save My Child (Terryroons/Educational, 2/22/35). Amazingly, a Terry episode that does not seem to lift any shots or copy any gags from prior Terry episodes (at least as far as I can presently detect). It stars as chief a nameless anthropomorphic pup, white with one black ear, whom Terry was regularly featuring in his mid-thirties product. Though he is humanized in his actions and behavior, he is visually something of a predecessor in appearance to Terry’s “new” creation of the following year, Puddy the Pup, though the latter would behave more as a real dog, as Terry’s answer to Pluto, on most occasions.

Fireman, Save My Child (Terryroons/Educational, 2/22/35). Amazingly, a Terry episode that does not seem to lift any shots or copy any gags from prior Terry episodes (at least as far as I can presently detect). It stars as chief a nameless anthropomorphic pup, white with one black ear, whom Terry was regularly featuring in his mid-thirties product. Though he is humanized in his actions and behavior, he is visually something of a predecessor in appearance to Terry’s “new” creation of the following year, Puddy the Pup, though the latter would behave more as a real dog, as Terry’s answer to Pluto, on most occasions.

The film opens with an unusual barber-shop style quartet number among the fire horses, who kill time with one of them playing a piano, adding his resonant bass voice to an original tune, “When the Gong in the Firehouse Rings Out.” Lip sync is unusually smooth on this sequence – a far cry from the awkward mouth movements still in use at Terry’s previous stomping grounds at Van Buren Studios. Terry in fact must be credited with having shown up his old bosses on synchronization practically fom the outset of founding his new studio – odd, for a man who lost his berth at Van Buren in the first place by resisting sound. It is of course uncertain if this technological advancement had anything to do with Terry’s own labors or industriousness, or was the contribution of his business partners at Audio-Cinema. Whatever the reason, Terry’s sound product was respectable, not only above the level of Van Buren, but others such as Walter Lantz, and even Max Fleischer, who often masked limited synchronization with muttered dialogue unaccompanied by lip movements, and post-recording of tracks after animation had been completed. The gong sung about by the horse quartet comes to life with its loud bongs, arousing the men – er, dogs – of the station. In an assembly-line setup, without need for the clothes to come to life as in earlier films in this article series. One dog mans a control handle operating a dispenser box next to the fire pole, placing firemen’s pants one by one on a telephone extender, as each dog jumps into his trousers before descending the pole. They land on a conveyer belt below, upon which their boots roll out to receive them. One hop off the belt, and their fireman’s axe is dispensed from an overhead chute. The old favorite gag of multiple studios has a crowd line up outside the station door to see the engines, only to have them emerge from the side wall. To vary things up, the crowd shifts position to the side wall, hoping to see more of the equipment coming out – and miss the hook and ladder trucks entirely, which exit properly through the front door. The upper floors of another tall building are alight, with one character running back and forth atop the roof above. A well-detailed shot depicts a typical New York-style traffic intersection between the tall skyscrapers, loaded with endless streams of cross-traffic passing in opposite directions and making turns. The sound of the sirens sends every car, and the intersection’s traffic cop, shimmying up the sides of the buildings, clearing the streets to let the engines pass. The dogs’ pumper engine isn’t exactly a power house – containing no actual boiler, but merely an old pot-bellied stove, complete with whistling tea-kettle atop its stovelid.

The film opens with an unusual barber-shop style quartet number among the fire horses, who kill time with one of them playing a piano, adding his resonant bass voice to an original tune, “When the Gong in the Firehouse Rings Out.” Lip sync is unusually smooth on this sequence – a far cry from the awkward mouth movements still in use at Terry’s previous stomping grounds at Van Buren Studios. Terry in fact must be credited with having shown up his old bosses on synchronization practically fom the outset of founding his new studio – odd, for a man who lost his berth at Van Buren in the first place by resisting sound. It is of course uncertain if this technological advancement had anything to do with Terry’s own labors or industriousness, or was the contribution of his business partners at Audio-Cinema. Whatever the reason, Terry’s sound product was respectable, not only above the level of Van Buren, but others such as Walter Lantz, and even Max Fleischer, who often masked limited synchronization with muttered dialogue unaccompanied by lip movements, and post-recording of tracks after animation had been completed. The gong sung about by the horse quartet comes to life with its loud bongs, arousing the men – er, dogs – of the station. In an assembly-line setup, without need for the clothes to come to life as in earlier films in this article series. One dog mans a control handle operating a dispenser box next to the fire pole, placing firemen’s pants one by one on a telephone extender, as each dog jumps into his trousers before descending the pole. They land on a conveyer belt below, upon which their boots roll out to receive them. One hop off the belt, and their fireman’s axe is dispensed from an overhead chute. The old favorite gag of multiple studios has a crowd line up outside the station door to see the engines, only to have them emerge from the side wall. To vary things up, the crowd shifts position to the side wall, hoping to see more of the equipment coming out – and miss the hook and ladder trucks entirely, which exit properly through the front door. The upper floors of another tall building are alight, with one character running back and forth atop the roof above. A well-detailed shot depicts a typical New York-style traffic intersection between the tall skyscrapers, loaded with endless streams of cross-traffic passing in opposite directions and making turns. The sound of the sirens sends every car, and the intersection’s traffic cop, shimmying up the sides of the buildings, clearing the streets to let the engines pass. The dogs’ pumper engine isn’t exactly a power house – containing no actual boiler, but merely an old pot-bellied stove, complete with whistling tea-kettle atop its stovelid.

The chief’s engine makes use of a young pup upon the hood, who constantly wags his tail in friendly manner – the tail being tied by a rope to the fire bell, clanging it continuously as they proceed down the street. The hook and ladder arrives at the base of the burning building, hitting the curb. The jolt tosses four long ladders into perfect position, leaning against the building, so that the crew can begin their ascent to the windows. The chief grabs the fire hose, but before hooking it up to the hydrant, ushers about a dozen of his men to crawl into the hose itself. He then hooks the hose up and turns on the water jetting his crewmen up to the roof, where they begin swinging their axes at everything in sight, singing a song about everything needing to be chopped to bits (which they demonstrate bu intentionally wrecking wheelbarrows of fine China). Four firemen attack the blaze with high pressure hoses, shot from the rooftop of an adjacent building. The streams of H20 flood the interior apartments, forcing all the furniture out the windows on the opposite side of the building, as well as a character in a bathtub, who rows against the current to pick up a few passengers from a window above, before riding a jet of water back to the ground. A lader is raised to a mile-long dachshund in a window, who snakes down to safety in and out between the rungs of the ladder, while the orchestra plays, “Go In and Out the Window,” The chief knocks the top off a hydrant, and rides the water plume to an upper floor, where he spritzes the contents of a fire extinguisher into one window, while spitting saliva at another jet of flame above. A blast from one of the hoses behind him knocks the chief into the window, where he encounters a large flame-man, who chases him and periodically makes things hot for the chief by zipping between his legs. The chief finds a shovel and attempts to squash the fire – but only divides it into about seven little ones. Cornered back at the original widow, the chief holds off the little flames with hand-to-hand fisticuffs (a good way to get third-degree burns on your knuckles). The fire crew on the opposite building roof focuses a spray of water at the window, and the chief performs the old “bridging”: gag from “Alice the Fire Fighter”, running atop the water to the opposite roof and safety. By now, the fire has progressed so that the remaining occupants of the burning building are jumping out of windows. The crew below, using a small net, has no sense of direction, and misses every jumper, letting them bounce off the pavement. Finally, someone gets smart and hauls in a net three times larger, and they actually succeed in catching one jumper safely. But a portly female pig, carrying a parrot in a cage, starts singing/screaming “Who will save me?” The crew races into position, while the pig states here I come, ready or not. She dives, and repeats for the closing the old gag of driving the net and the firemen into a crater in the ground, from which they all climb out – with the pig and parrot the last ones in the hole, nevertheless happy to be safe and sound.

The chief’s engine makes use of a young pup upon the hood, who constantly wags his tail in friendly manner – the tail being tied by a rope to the fire bell, clanging it continuously as they proceed down the street. The hook and ladder arrives at the base of the burning building, hitting the curb. The jolt tosses four long ladders into perfect position, leaning against the building, so that the crew can begin their ascent to the windows. The chief grabs the fire hose, but before hooking it up to the hydrant, ushers about a dozen of his men to crawl into the hose itself. He then hooks the hose up and turns on the water jetting his crewmen up to the roof, where they begin swinging their axes at everything in sight, singing a song about everything needing to be chopped to bits (which they demonstrate bu intentionally wrecking wheelbarrows of fine China). Four firemen attack the blaze with high pressure hoses, shot from the rooftop of an adjacent building. The streams of H20 flood the interior apartments, forcing all the furniture out the windows on the opposite side of the building, as well as a character in a bathtub, who rows against the current to pick up a few passengers from a window above, before riding a jet of water back to the ground. A lader is raised to a mile-long dachshund in a window, who snakes down to safety in and out between the rungs of the ladder, while the orchestra plays, “Go In and Out the Window,” The chief knocks the top off a hydrant, and rides the water plume to an upper floor, where he spritzes the contents of a fire extinguisher into one window, while spitting saliva at another jet of flame above. A blast from one of the hoses behind him knocks the chief into the window, where he encounters a large flame-man, who chases him and periodically makes things hot for the chief by zipping between his legs. The chief finds a shovel and attempts to squash the fire – but only divides it into about seven little ones. Cornered back at the original widow, the chief holds off the little flames with hand-to-hand fisticuffs (a good way to get third-degree burns on your knuckles). The fire crew on the opposite building roof focuses a spray of water at the window, and the chief performs the old “bridging”: gag from “Alice the Fire Fighter”, running atop the water to the opposite roof and safety. By now, the fire has progressed so that the remaining occupants of the burning building are jumping out of windows. The crew below, using a small net, has no sense of direction, and misses every jumper, letting them bounce off the pavement. Finally, someone gets smart and hauls in a net three times larger, and they actually succeed in catching one jumper safely. But a portly female pig, carrying a parrot in a cage, starts singing/screaming “Who will save me?” The crew races into position, while the pig states here I come, ready or not. She dives, and repeats for the closing the old gag of driving the net and the firemen into a crater in the ground, from which they all climb out – with the pig and parrot the last ones in the hole, nevertheless happy to be safe and sound.

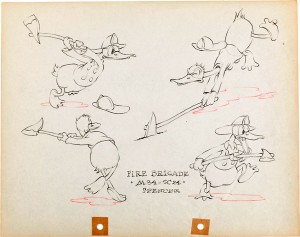

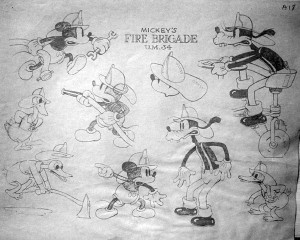

Looking a good three years ahead of his time, Disney provides us with a Technicolor masterpiece, Mickey’s Fire Brigade (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 8/3/35 – Ben Sharpsteen, dir.), an action-packed romp for Mickey, Donald, and Goofy, that appears to reuse no material whatsoever from the earlier “The Fire Fighters”. An impressive opening title, thankfully preserved from lack of a theatrical reissue, has the entire titles ignite from the bottom and burn up, revealing view of a multi-story boarding house erupting in visible flames at each window and along the eaves of the roof, with scores of characters jumping from windows, or attempting to carry furniture out of them and over the porch roof. A delightfully detailed shot presents sight of a hook and ladder truck proceeding straight at the cameras, then making a left turn just shy of the lens, to reveal Fire Chief Mickey at the wheel, Donald excitedly jumping atop the ladder, and Goofy bringing up the rear, steering the rear end of the ladder by riding a unicycle wheel while holding onto the rungs. The trio slam on the brakes at the fire scene with such suddenness, four of their ladders fly off of the engine (similar to Terry’s gag above!). They race for the hydrant, all carrying portions of the hose, and cross each other up in a tangled mess. Mickey breaks free, opens the hydrant cover, and attempts to screw on the hose. Painfully, he has grabbed Goofy’s foot by mistake, and twists the poor dog’s ankle into a braid before discovering the error, releasing his shoe to allow the leg to speedily unwind. Donald tries to get to the heart of the action through a cellar door – releasing a jet of flame that springs up under him, causing him to leap upwards into a third story window. Goofy tries to gain entry through a rear door, but receives a beating from a cloud of black smoke, which forms fists to deliver a one-two punch, then a foot to boot him out the door. Donald, now inside, runs around a living room with an empty fire pail, scooping up small running flames from the carpet, and depositing them in the water of a nearby goldfish bowl. The goldfish rises from the water sur face, to exhale a series of smoke rings. Meanwhile, Mickey finally has the hose attached to the hydrant, and turns it on. He is still, however, wrapped up in loops of the hose, and the water pressure unrolls him like a jelly roll, over the lawn and straight up a ladder leaning against the building. The hose length runs out precisely at the top rung of the ladder, fortunately leaving Mickey in perfect position to aim the nozzle into an upper-story window. Things look good, until the flame forms hands, which take hold of the window frame from inside, and shut the window in Mickey’s face. The force of the water now ricochets off the glass back at Mickey, knocking him off the ladder. With no bracing, the hose’s forceful water transforms the hose line into a runaway serpentine zig-zag of curves and arcs in mid-air, with Mickey along for the ride. A fantastic dimensional shot shows the panicked mouse juxtaposed against a background about five stories below him, with water shooting every which way, then directly at the camera, drenching the lens to obliterate the view, until the water drips away from the lens glass to restore the scene ti crystal clarity! As the hose end droops in a pass close to the building, the flaming hands extend out another window and grab the nozzle, turning its aim upon Mickey to knock him off. Mickey falls upon the hook and ladder truck, against the switch which activates the extension ladder. With his foot caught in a rung, the ladder extends like a bullet fired, shooting Mickey directly at the closed upper-story window, and right through the glass, then emerging out of the roof shingles. The ladder end now carries various bric-a-brac from the apartment inside, including a large chest of drawers – then abruptly runs out of extension mileage, and stops cold. Mickey emerges from one of the drawers of the dresser, and steps out – into space. Quickly realizing his mistake, he darts back inside the drawer, and lingers there with only his eyes visible, wondering what to do next.

Looking a good three years ahead of his time, Disney provides us with a Technicolor masterpiece, Mickey’s Fire Brigade (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 8/3/35 – Ben Sharpsteen, dir.), an action-packed romp for Mickey, Donald, and Goofy, that appears to reuse no material whatsoever from the earlier “The Fire Fighters”. An impressive opening title, thankfully preserved from lack of a theatrical reissue, has the entire titles ignite from the bottom and burn up, revealing view of a multi-story boarding house erupting in visible flames at each window and along the eaves of the roof, with scores of characters jumping from windows, or attempting to carry furniture out of them and over the porch roof. A delightfully detailed shot presents sight of a hook and ladder truck proceeding straight at the cameras, then making a left turn just shy of the lens, to reveal Fire Chief Mickey at the wheel, Donald excitedly jumping atop the ladder, and Goofy bringing up the rear, steering the rear end of the ladder by riding a unicycle wheel while holding onto the rungs. The trio slam on the brakes at the fire scene with such suddenness, four of their ladders fly off of the engine (similar to Terry’s gag above!). They race for the hydrant, all carrying portions of the hose, and cross each other up in a tangled mess. Mickey breaks free, opens the hydrant cover, and attempts to screw on the hose. Painfully, he has grabbed Goofy’s foot by mistake, and twists the poor dog’s ankle into a braid before discovering the error, releasing his shoe to allow the leg to speedily unwind. Donald tries to get to the heart of the action through a cellar door – releasing a jet of flame that springs up under him, causing him to leap upwards into a third story window. Goofy tries to gain entry through a rear door, but receives a beating from a cloud of black smoke, which forms fists to deliver a one-two punch, then a foot to boot him out the door. Donald, now inside, runs around a living room with an empty fire pail, scooping up small running flames from the carpet, and depositing them in the water of a nearby goldfish bowl. The goldfish rises from the water sur face, to exhale a series of smoke rings. Meanwhile, Mickey finally has the hose attached to the hydrant, and turns it on. He is still, however, wrapped up in loops of the hose, and the water pressure unrolls him like a jelly roll, over the lawn and straight up a ladder leaning against the building. The hose length runs out precisely at the top rung of the ladder, fortunately leaving Mickey in perfect position to aim the nozzle into an upper-story window. Things look good, until the flame forms hands, which take hold of the window frame from inside, and shut the window in Mickey’s face. The force of the water now ricochets off the glass back at Mickey, knocking him off the ladder. With no bracing, the hose’s forceful water transforms the hose line into a runaway serpentine zig-zag of curves and arcs in mid-air, with Mickey along for the ride. A fantastic dimensional shot shows the panicked mouse juxtaposed against a background about five stories below him, with water shooting every which way, then directly at the camera, drenching the lens to obliterate the view, until the water drips away from the lens glass to restore the scene ti crystal clarity! As the hose end droops in a pass close to the building, the flaming hands extend out another window and grab the nozzle, turning its aim upon Mickey to knock him off. Mickey falls upon the hook and ladder truck, against the switch which activates the extension ladder. With his foot caught in a rung, the ladder extends like a bullet fired, shooting Mickey directly at the closed upper-story window, and right through the glass, then emerging out of the roof shingles. The ladder end now carries various bric-a-brac from the apartment inside, including a large chest of drawers – then abruptly runs out of extension mileage, and stops cold. Mickey emerges from one of the drawers of the dresser, and steps out – into space. Quickly realizing his mistake, he darts back inside the drawer, and lingers there with only his eyes visible, wondering what to do next.

Donald’s battle begins to look like Flip the Frog’s, as he chops at various flames with his axe, repeating the old gag of dividing them in two. One flame runs up the decorative pole of a floor lamp, its base shaped like a semi-nude female figurine. Donald slashes at the pole just above the statue figure, causing the lampshade to fall, landing as a new skirt around the statue’s waist to provide a sense of modesty (a variant on a similar gag from Betty Boop’s “Minnie the Moocher”). Donald next moves to a piano, where little flames dance on the keyboard, playing with their feet a rendition of “Who’s Afraid Of the Big Bad Wolf?”. only to have the fire bring down the piano’s wooden lid on Donald’s head (a setup similar to Fleischer’s “Fire Bigs”). Three borrowed gags in a row? Time to get back to original material. Cue Goofy, who is doing something to live up to his name. Goofy attempts to save all manner of furniture, by tossing it out of an upper-story window. His aim, however, infallibly lands each item directly in the smokestack of the lit boiler of the pumper on the engine, incinerating each item into ashes almost immediately upon impact. The goof next tosses out a serving table with expanding wooden “wings” on hinges. It opens to full wingspan, then soars back into the window, just as Goofy is about to jettison some chinaware and a tablecloth. Knocking Goofy backwards, the table pins him against te wall, while the tablecloth and chinaware form into a perfect place setting for an afternoon refreshment break – complete with tea and doughnuts! Why fight it? Goofy settles down to fully enjoy the snacks, forgetting entirely about the fire. Back to Donald, who has now had the tables turned, with the flames wielding the fire axe and chasing him instead. Donald ducks (no pun intended) under a carpet, and the flames follow as little lumps visible through the rug. Donald emerges on the other side, crashing into a small table, on which is stored a supply of fly paper. Donald gets creative, and tosses sheets of the stuff in front of the point where the flames will emerge from the carpet. Sure enough, the little flames get their feet trapped in the gooey stuff, and somehow are unable to burn through the sticky paper. Donald runs for a pail of water to throw upon them. However, though trapped, the flames remain resourceful. They lean toward each other to merge as one large flame, which develops arms to yank the pail from Donald’s grasp, and drench him with it. We return to Mickey in the dresser drawer outside, as the ladder leans slightly, allowing the respective drawers to slide out. Mickey leaps from one drawer to another to stay with the ladder, then clings onto the dresser’s rotating mirror while dodging flame touching at his rear end. In a surreal moment of inspiration, Mickey produces from his pocket a pair of scissors, and uses them to snip the forward points off of the upper-reaches of the flame, leaving the flame with a hopeless straight-edge, unable to affect the mouse. Donald and Goofy join forces to finally get some rugs and furniture successfully out the window, then idiotically decide that they should also rescue a brick fireplace against an inner wall, in which a fire is still burning. They pry the structure loose from the wall and begin lugging it to the window, just as the flames on the roof finally decide what to do with the mouse, by forming into the shape of a pair of shears, and snipping off the ends of the ladder holding up Mickey’s dresser. The ladder snaps and collapses, tossing Mickey down the chimney, where he comes out right into the fireplace Donald and Goofy are rescuing, demolishing it. Little has been accomplished. But the trio are now back together.

Donald’s battle begins to look like Flip the Frog’s, as he chops at various flames with his axe, repeating the old gag of dividing them in two. One flame runs up the decorative pole of a floor lamp, its base shaped like a semi-nude female figurine. Donald slashes at the pole just above the statue figure, causing the lampshade to fall, landing as a new skirt around the statue’s waist to provide a sense of modesty (a variant on a similar gag from Betty Boop’s “Minnie the Moocher”). Donald next moves to a piano, where little flames dance on the keyboard, playing with their feet a rendition of “Who’s Afraid Of the Big Bad Wolf?”. only to have the fire bring down the piano’s wooden lid on Donald’s head (a setup similar to Fleischer’s “Fire Bigs”). Three borrowed gags in a row? Time to get back to original material. Cue Goofy, who is doing something to live up to his name. Goofy attempts to save all manner of furniture, by tossing it out of an upper-story window. His aim, however, infallibly lands each item directly in the smokestack of the lit boiler of the pumper on the engine, incinerating each item into ashes almost immediately upon impact. The goof next tosses out a serving table with expanding wooden “wings” on hinges. It opens to full wingspan, then soars back into the window, just as Goofy is about to jettison some chinaware and a tablecloth. Knocking Goofy backwards, the table pins him against te wall, while the tablecloth and chinaware form into a perfect place setting for an afternoon refreshment break – complete with tea and doughnuts! Why fight it? Goofy settles down to fully enjoy the snacks, forgetting entirely about the fire. Back to Donald, who has now had the tables turned, with the flames wielding the fire axe and chasing him instead. Donald ducks (no pun intended) under a carpet, and the flames follow as little lumps visible through the rug. Donald emerges on the other side, crashing into a small table, on which is stored a supply of fly paper. Donald gets creative, and tosses sheets of the stuff in front of the point where the flames will emerge from the carpet. Sure enough, the little flames get their feet trapped in the gooey stuff, and somehow are unable to burn through the sticky paper. Donald runs for a pail of water to throw upon them. However, though trapped, the flames remain resourceful. They lean toward each other to merge as one large flame, which develops arms to yank the pail from Donald’s grasp, and drench him with it. We return to Mickey in the dresser drawer outside, as the ladder leans slightly, allowing the respective drawers to slide out. Mickey leaps from one drawer to another to stay with the ladder, then clings onto the dresser’s rotating mirror while dodging flame touching at his rear end. In a surreal moment of inspiration, Mickey produces from his pocket a pair of scissors, and uses them to snip the forward points off of the upper-reaches of the flame, leaving the flame with a hopeless straight-edge, unable to affect the mouse. Donald and Goofy join forces to finally get some rugs and furniture successfully out the window, then idiotically decide that they should also rescue a brick fireplace against an inner wall, in which a fire is still burning. They pry the structure loose from the wall and begin lugging it to the window, just as the flames on the roof finally decide what to do with the mouse, by forming into the shape of a pair of shears, and snipping off the ends of the ladder holding up Mickey’s dresser. The ladder snaps and collapses, tossing Mickey down the chimney, where he comes out right into the fireplace Donald and Goofy are rescuing, demolishing it. Little has been accomplished. But the trio are now back together.

The finale of the film again takes definite inspiration from the theme of Fleischer’s Fire Bugs, presenting the boys with the task of saving a victim who doesn’t want saving. Inside a nearby bathroom, the boys hear the operatic notes of Clarabelle Cow, luxuriating in a bubble bath and oblivious to the inferno around her. “There’s a woman up there”, shouts Mickey to his crew, and the boys race up a flight of stairs, with the flames burning up each step right behind the feet of the racing Donald. Reaching the bathroom door, Mickey and Donald provide footholds to boost Goofy up to the transom window above the door to peer in. The moment Clara spots Goofy’s eyes peering at her, she screams, and tries to cover herself with a towel. Goofy attempts to get a word in edgewise, to inform her that her house is on fire, but is interrupted by so many calls by Clarabelle for help and for the police, he can never complete the sentence, and utters nonsense phrases like, “Lady, your fire is on house.” Seeing they are getting nowhere, Mickey gives order to break down the door. They do this by using the rigidly-posed Goofy as a battering ram, bashing him headfirst through the door, then across the room into the drain of an open sink. Tugging to yank him out of the drain, a gag shot reveals the sink to be clogged with numerous other items which spill out, including, among others, a razor, a pair of scissors, a tooth comb, a string of pearls, razor blades, a toothbrush and full set of false teeth, an engagement ring, a Swiss army knife, and finally, a pair of loaded dice. The boys can see the only way to get Clarabelle out of the room is to transport her, tub and all, out the window. They lift the porcelain receptacle bodily, while Clarabelle continues her screams and bashes them on the heads with a bath brush. The tub is dragged out onto the roof, but slides on the slanted surface uncontrolled, dragging the boys along. The tub hits the end of the extension ladder, shifting it away from the building, leaving our trailing heroes suspended like a monkey chain between ladder rungs and roof edge, while the bathtub slides down the ladder rungs, coming to rest upon and partially wrecking the engine below. A flame attacks Donald’s rear end, causing him to lose hold of the roof edge. The boys now pile onto the shoulders of Goofy, who is balancing on the ladder posts like stilts, and the three fall, right into the tub with Clarabelle. They are greeted not with a hero’s welcome, but with more brush bashing from the cow, driving them underwater. The last blow is scored upon Donald’s rear end as he comes up upside down, causing the duck to react in confusion as the film irises out.

The finale of the film again takes definite inspiration from the theme of Fleischer’s Fire Bugs, presenting the boys with the task of saving a victim who doesn’t want saving. Inside a nearby bathroom, the boys hear the operatic notes of Clarabelle Cow, luxuriating in a bubble bath and oblivious to the inferno around her. “There’s a woman up there”, shouts Mickey to his crew, and the boys race up a flight of stairs, with the flames burning up each step right behind the feet of the racing Donald. Reaching the bathroom door, Mickey and Donald provide footholds to boost Goofy up to the transom window above the door to peer in. The moment Clara spots Goofy’s eyes peering at her, she screams, and tries to cover herself with a towel. Goofy attempts to get a word in edgewise, to inform her that her house is on fire, but is interrupted by so many calls by Clarabelle for help and for the police, he can never complete the sentence, and utters nonsense phrases like, “Lady, your fire is on house.” Seeing they are getting nowhere, Mickey gives order to break down the door. They do this by using the rigidly-posed Goofy as a battering ram, bashing him headfirst through the door, then across the room into the drain of an open sink. Tugging to yank him out of the drain, a gag shot reveals the sink to be clogged with numerous other items which spill out, including, among others, a razor, a pair of scissors, a tooth comb, a string of pearls, razor blades, a toothbrush and full set of false teeth, an engagement ring, a Swiss army knife, and finally, a pair of loaded dice. The boys can see the only way to get Clarabelle out of the room is to transport her, tub and all, out the window. They lift the porcelain receptacle bodily, while Clarabelle continues her screams and bashes them on the heads with a bath brush. The tub is dragged out onto the roof, but slides on the slanted surface uncontrolled, dragging the boys along. The tub hits the end of the extension ladder, shifting it away from the building, leaving our trailing heroes suspended like a monkey chain between ladder rungs and roof edge, while the bathtub slides down the ladder rungs, coming to rest upon and partially wrecking the engine below. A flame attacks Donald’s rear end, causing him to lose hold of the roof edge. The boys now pile onto the shoulders of Goofy, who is balancing on the ladder posts like stilts, and the three fall, right into the tub with Clarabelle. They are greeted not with a hero’s welcome, but with more brush bashing from the cow, driving them underwater. The last blow is scored upon Donald’s rear end as he comes up upside down, causing the duck to react in confusion as the film irises out.

More than once discussed in these columns and elsewhere on this site, Betty Boop and Grampy (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 8/16/35, Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Tendlar/Charles Hastings, anim.), receives the briefest of honorable mentions. When Betty receives a telegram from Grampy inviting her to a big party at his place, it includes the instruction, “Bring the gang.” The heretofore unknown “gang” of the community includes two moving men, a traffic cop, and a fireman. The fireman is busy and in the middle of a rescue of a woman from the upper-story window of a burning building, in the process of carrying her down a ladder. Betty and the others hail him from the street about the party “Over at Grampy’s house”, and the fireman is not about to miss out on such an opportunity. He decides to literally drop what he is doing, jamming the young lady he is carrying between the rungs of the fire ladder, to wait helplessly for him to return while he attends the party (all the while hoping that the fire doesn’t consume the building the ladder is leaning on first!).

More than once discussed in these columns and elsewhere on this site, Betty Boop and Grampy (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 8/16/35, Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Tendlar/Charles Hastings, anim.), receives the briefest of honorable mentions. When Betty receives a telegram from Grampy inviting her to a big party at his place, it includes the instruction, “Bring the gang.” The heretofore unknown “gang” of the community includes two moving men, a traffic cop, and a fireman. The fireman is busy and in the middle of a rescue of a woman from the upper-story window of a burning building, in the process of carrying her down a ladder. Betty and the others hail him from the street about the party “Over at Grampy’s house”, and the fireman is not about to miss out on such an opportunity. He decides to literally drop what he is doing, jamming the young lady he is carrying between the rungs of the fire ladder, to wait helplessly for him to return while he attends the party (all the while hoping that the fire doesn’t consume the building the ladder is leaning on first!).

Another brief mention may be in order of The Lady In Red (Warner, Merie Melodies (2-strip Technicolor), 9/21/35 – Isadore (Friz) Freleng, dir.), which, while featuring no fire-fighting, does feature a fire. Activities take place at a border town Mexican cantina – not among its human patrons (if any), but among its infestation of “cucarachas”, who attend in droves to watch the exotic dancing of a female of the species, known as the Lady in Red. Trouble brews when a pet parrot wanders into the scene, and catches up the cantica dancer in his beak. A brave young cockroach follows the bird as he carries the damsel into the cantina kitchen, and over the top of the burners of an old gas stove. Seeing his chance, the male turns the handle to ignite one of the gas jets. Flame shoots out of the burner, catching the parrot’s tail feathers and setting them alight. The parrot squawks in hysteria, dropping the damsel, and soars in panicked flight round and round the cantina, then out the window, leaving a trail of black smoke streaming from his tail. While the lady embraces her “hero”, the final shot shows the parrot still making dizzying loops in the sky, the smoke skywriting in cursive lettering, “The End.”

Another brief mention may be in order of The Lady In Red (Warner, Merie Melodies (2-strip Technicolor), 9/21/35 – Isadore (Friz) Freleng, dir.), which, while featuring no fire-fighting, does feature a fire. Activities take place at a border town Mexican cantina – not among its human patrons (if any), but among its infestation of “cucarachas”, who attend in droves to watch the exotic dancing of a female of the species, known as the Lady in Red. Trouble brews when a pet parrot wanders into the scene, and catches up the cantica dancer in his beak. A brave young cockroach follows the bird as he carries the damsel into the cantina kitchen, and over the top of the burners of an old gas stove. Seeing his chance, the male turns the handle to ignite one of the gas jets. Flame shoots out of the burner, catching the parrot’s tail feathers and setting them alight. The parrot squawks in hysteria, dropping the damsel, and soars in panicked flight round and round the cantina, then out the window, leaving a trail of black smoke streaming from his tail. While the lady embraces her “hero”, the final shot shows the parrot still making dizzying loops in the sky, the smoke skywriting in cursive lettering, “The End.”

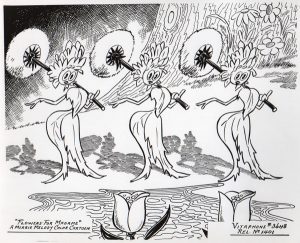

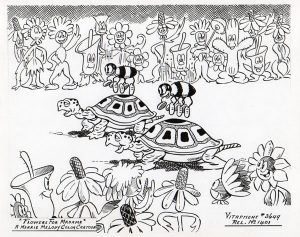

Quite a bit of confusion has happened over the years as to the origin date and production order of Flowers For Madame (Warner, Merrie Melodies (3-strip Technicolor – Isadore (Friz) Freleng, dir.), possibly originating from a likely error in the filmography of Leonard Maltin’s “Of Mice and Magic”. Probably due in large part to the loss of original titles when this film went to “Blue Ribbon Merrie Melodies” re-release, confusion persisted as to whether this episode was just a rank-and-file entry amidst other full-Technicolor releases during early 1936, or a groundbreaker predating the earliest confirmed uncut full-Technicolor negative. I Wanna Play House (1/18/36), which for many years was mis-attributed the status of being Warner’s first three-strip cartoon. Some web contributors even speculated that “Flowers” might be in two-strip color rather than three. This debunked theory probably developed from poorly struck and faded 16mm prints which circulated from AAP syndication, coupled with the unusual use on some characters of an odd shade of green quite similar to the blue-green hues seen on previous two-strip cartoons. The paint use is probably easily explained – with the conversion to full color, the old bluegreen paint would no longer be in vogue for use upon the new projects – so a decision to cast a few characters in such shade would allow the painters to simply burn out the existing paint supply and make room on the shelves for more vibrant colors. The presence otherwise throughout the film of easily discernable blues and bright greens on restored prints denotes that the film stock was indeed 3-strip after all. Another giveaway as to the stock used is the closing music cue of the film, which, on existing Blue Ribbon prints abruptly breaks into the middle of a musical riff to switch to a 1940’s-style closing cue of “Merrily We Roll Along” for the newly-shot “That’s All Folks”. Had this been a two-strip cartoon, it would have followed the style of previous episodes such as The Lady in Red, with the music closing cleanly at the same time as the iris out, followed by stock shot of an animated court jester announcing verbally, “That’s all, folks”. So it is conclusive that no two-strip footage was used in this production. What of the release date? Maltin’s book attributes the date to 4/6/36, while current internet sources state 11/20/35. The new dating makes more sense, as it fills in a hole in the Maltin filmography, which failed to list any Warner cartoon releases for the months of November and December, 1935. Furthermore, the festive and colorful pageant of flowers presented in the film would seem a more likely choice for first move into full-Technicolor than the “Play House” scenario, which restricted most of its visuals to three bears and the interior of a camping trailer. Thus, through recent research and deduction, this film appears to have regained its rightful place as Warner’s first rainbow-hued Merrie Melodie, celebrating the expiration of Disney’s exclusive rights to the process.

Quite a bit of confusion has happened over the years as to the origin date and production order of Flowers For Madame (Warner, Merrie Melodies (3-strip Technicolor – Isadore (Friz) Freleng, dir.), possibly originating from a likely error in the filmography of Leonard Maltin’s “Of Mice and Magic”. Probably due in large part to the loss of original titles when this film went to “Blue Ribbon Merrie Melodies” re-release, confusion persisted as to whether this episode was just a rank-and-file entry amidst other full-Technicolor releases during early 1936, or a groundbreaker predating the earliest confirmed uncut full-Technicolor negative. I Wanna Play House (1/18/36), which for many years was mis-attributed the status of being Warner’s first three-strip cartoon. Some web contributors even speculated that “Flowers” might be in two-strip color rather than three. This debunked theory probably developed from poorly struck and faded 16mm prints which circulated from AAP syndication, coupled with the unusual use on some characters of an odd shade of green quite similar to the blue-green hues seen on previous two-strip cartoons. The paint use is probably easily explained – with the conversion to full color, the old bluegreen paint would no longer be in vogue for use upon the new projects – so a decision to cast a few characters in such shade would allow the painters to simply burn out the existing paint supply and make room on the shelves for more vibrant colors. The presence otherwise throughout the film of easily discernable blues and bright greens on restored prints denotes that the film stock was indeed 3-strip after all. Another giveaway as to the stock used is the closing music cue of the film, which, on existing Blue Ribbon prints abruptly breaks into the middle of a musical riff to switch to a 1940’s-style closing cue of “Merrily We Roll Along” for the newly-shot “That’s All Folks”. Had this been a two-strip cartoon, it would have followed the style of previous episodes such as The Lady in Red, with the music closing cleanly at the same time as the iris out, followed by stock shot of an animated court jester announcing verbally, “That’s all, folks”. So it is conclusive that no two-strip footage was used in this production. What of the release date? Maltin’s book attributes the date to 4/6/36, while current internet sources state 11/20/35. The new dating makes more sense, as it fills in a hole in the Maltin filmography, which failed to list any Warner cartoon releases for the months of November and December, 1935. Furthermore, the festive and colorful pageant of flowers presented in the film would seem a more likely choice for first move into full-Technicolor than the “Play House” scenario, which restricted most of its visuals to three bears and the interior of a camping trailer. Thus, through recent research and deduction, this film appears to have regained its rightful place as Warner’s first rainbow-hued Merrie Melodie, celebrating the expiration of Disney’s exclusive rights to the process.

Again, as with the choice of using fire for a flashy opening into the two-strip world of the studio’s prior production, Honeymoon Hotel, Warner does its best to copycat Disney in their own slightly-warped house style, choosing for their 3-color debut not only a cast of vegetation characters quite derivative of the concept of “Flowers and Trees”, but a climactic fire sequence almost directly deriving from the Disney classic as well. Everyone in plant-land is preparing parade floats for a Flower Pageant, to be judged for big prizes. A cactus wants to join the competition, and prepares an entry on the fly, with a wind-up toy construction tractor, and a seed from a clinging vine to entwine around the vehicle with a string of blue blossoms. He rides atop the hood of the entry in the parade, though the judges unanimously react by holding their noses. Then, the mainspring of the toy snaps, destroying the float, and sprawling the cactus upon the street, where he receives laughter and jeers as an object of public ridicule.

Again, as with the choice of using fire for a flashy opening into the two-strip world of the studio’s prior production, Honeymoon Hotel, Warner does its best to copycat Disney in their own slightly-warped house style, choosing for their 3-color debut not only a cast of vegetation characters quite derivative of the concept of “Flowers and Trees”, but a climactic fire sequence almost directly deriving from the Disney classic as well. Everyone in plant-land is preparing parade floats for a Flower Pageant, to be judged for big prizes. A cactus wants to join the competition, and prepares an entry on the fly, with a wind-up toy construction tractor, and a seed from a clinging vine to entwine around the vehicle with a string of blue blossoms. He rides atop the hood of the entry in the parade, though the judges unanimously react by holding their noses. Then, the mainspring of the toy snaps, destroying the float, and sprawling the cactus upon the street, where he receives laughter and jeers as an object of public ridicule.

Nearby, on a vacant lot, a mislaid magnifying glass in a trash heap ignites a box of red tip matches with a sunlight beam. A grass-fire grows and quickly spreads, heading in the direction of the pageant. Seeing the fires approach, spectators at the parade begin to run for their lives. A flame-man sets off after one of the posies, getting in some licks on the backside of its stem, before a lily acts as a scooper to fill its petals with water from a nearby rivulet, and douse the flame into oblivion. Another extension of the fire points its red-hot fingers under the body of a slow-moving snail, causing the creature to leap high in pain, then shift into impossibly high-gear to beat a retreat to a lily pad on the local pond. The main body of the blaze begins to surround the cactus, who flees to a residential lawn, finding there a circulating garden sprinkler, attached to a water pipe with valve sticking out of the ground. The cactus turns on the water flow, and the sprinkler provides him with a periodic ring of safety, tracing a circular perimeter of moisture around him and preventing the flame’s forward progress. The cactus jeers at the fire from his presumed position of safety – until another flame-man materializes, circles around behind the cactus, and slips into the circle’s center between the alternating jets of the sprinkler. Creeping up behind the cactus, he gives the plant a hot rear end. The cactus is forced out of the circle, while the flame-man shuts off the water valve, and beckons the rest of the fire to follow. The pursuit continues into a vegetable garden, where, to the cactus’s delight, he spots a bumper crop of watermelons. Grabbing up a sharp stick, the cactus hops atop each melon, plunging in the stick at the end of the melon nearest the fire. A spray of juice emerges from each melon, and the cactus repeats the process again and again – until there is enough high-power projection of refreshing fluid to extinguish the blaze almost entirely. The cactus receives an ovation from the returning crowd as a hero, to which he modestly grins and nods. Meanwhile the sole survivor of the blaze, the same flame-man who turned off the sprinkler, hides from the activity behind a soap box. A heretofore unseen grasshopper emerges into view around the opposite corner of the box, and utilizes his natural spitting ability, testing the wind and aiming a curve-shot of spit in an arc around the box, hitting the flame from the back-side to snuff him out. The grasshopper proudly gestures to the camera as if to say “Did you see that curve?”, as the film irises out.

A convincing recreation of the original titles for this film, with musical substitutions for the missing track (end coda of which sounds right on the money), is embedded below.

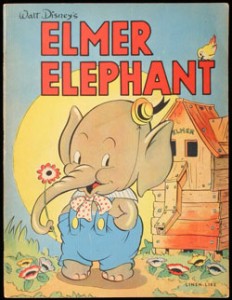

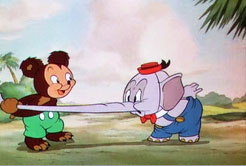

Elmer Elephant (Disney, Silly Symphony, 3/28/36 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.), again gives the Disney boys an opportunity to technically shine. Featuring an exceptionally large cast of junior jungle animals, the story centers on a children’s birthday party for popular Tillie Tiger, to which our title hero, young Elmer Elephant, has been sent an invitation. Bashful Elmer has selected a present of a small bouquet of flowers, which impresses Tillie, though raising the jealousy of others at the party – especially when Tillie offers Elmer a kiss. Elmer never quite receives the effect of the kiss, as his long trunk gets in the way of Tillie’s lips. The other guests decide that the troublesome trunk is their way to get Elmer’s goat, and begin a campaign of ridicule of the poor young suitor. Donning jungle foliage, old socks, and other items to disguise themselves as mock elephants, they mimic and poke fun at his long nose, publicly humiliating him and ousting him from the party while Tillie is taking a break in her treehouse high above the festivities. Their insulting song, “Your nose is like a rubber hose”, resounds in Elmer’s ears, and is even taken up by a hippopotamus in attendance, whose own huge snout should rightfully have subjected him to an equal degree of ridicule. Elmer wanders off into the jungle, pausing beside a stream and attempting to find ways to conceal his natural “blemish”, such as rolling his trunk into a ball, then trying to hold it in with the elastic strap of his hat. Nothing works, and all Elmer sees of himself is a reflection in the water distorting his trunk to look as if a mile ling. An encouraging word is finally heard from high above, as a voice seemingly from nowhere inquires if he is having “Nose trouble?”. The voice (that of Pinto Colvig, in the manner of an old man, similar in timbre to Practical Pig) comes from a mile-tall giraffe, who points out that they used to make fun of him, too, but now he doesn’t care. He also indicates there are plenty of others who could be considered “funny looking”, pointing to three pelicans perched nearby, with schnozzles worth of Jimmy Durante. Elmer smiles, and takes heart, realizing he is not alone, and that someone understands him.

Elmer Elephant (Disney, Silly Symphony, 3/28/36 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.), again gives the Disney boys an opportunity to technically shine. Featuring an exceptionally large cast of junior jungle animals, the story centers on a children’s birthday party for popular Tillie Tiger, to which our title hero, young Elmer Elephant, has been sent an invitation. Bashful Elmer has selected a present of a small bouquet of flowers, which impresses Tillie, though raising the jealousy of others at the party – especially when Tillie offers Elmer a kiss. Elmer never quite receives the effect of the kiss, as his long trunk gets in the way of Tillie’s lips. The other guests decide that the troublesome trunk is their way to get Elmer’s goat, and begin a campaign of ridicule of the poor young suitor. Donning jungle foliage, old socks, and other items to disguise themselves as mock elephants, they mimic and poke fun at his long nose, publicly humiliating him and ousting him from the party while Tillie is taking a break in her treehouse high above the festivities. Their insulting song, “Your nose is like a rubber hose”, resounds in Elmer’s ears, and is even taken up by a hippopotamus in attendance, whose own huge snout should rightfully have subjected him to an equal degree of ridicule. Elmer wanders off into the jungle, pausing beside a stream and attempting to find ways to conceal his natural “blemish”, such as rolling his trunk into a ball, then trying to hold it in with the elastic strap of his hat. Nothing works, and all Elmer sees of himself is a reflection in the water distorting his trunk to look as if a mile ling. An encouraging word is finally heard from high above, as a voice seemingly from nowhere inquires if he is having “Nose trouble?”. The voice (that of Pinto Colvig, in the manner of an old man, similar in timbre to Practical Pig) comes from a mile-tall giraffe, who points out that they used to make fun of him, too, but now he doesn’t care. He also indicates there are plenty of others who could be considered “funny looking”, pointing to three pelicans perched nearby, with schnozzles worth of Jimmy Durante. Elmer smiles, and takes heart, realizing he is not alone, and that someone understands him.

This scene is disrupted by the sound of shouts, bells, and sirens – and the aroma of smoke, picked up by the nose of the giraffe high above in the air. “Must be a fire somewhere”, he remarks. Yes, indeed – at Tillie’s house! From undisclosed causes, a blaze is attacking the bamboo treehouse high above the partygoers, and they watch helplessly from around the base of the tree, while Tillie attempts to beat back the advance of the flames alone, batting at them with a broom. A local fire department bravely answers the call, consisting of dozens of monkeys on a mile-long hook and ladder, and a chief riding in a separate wagon pulled by an ostrich (whom he has to prod from burying head in the sand by spritzing the bird with a seltzer bottle). Just before the fire company arrives, Tillie prepares to jump into a makeshift net carried by her party guests. But the flame transforms into a hand to grab her back by the tail, then divides into little flames that jump from the treehouse balcony onto the net below, burning it from the center outwards and scattering the party guests. The monkeys arrive and raise the rickety extension latter, scrambling up it one after another. The flame responds by jumping onto the ladder from the top, and following it down, setting it ablaze. The monkeys pull a fast 180 degree turn, and scramble back down the ladder in terror (animated with marvelous energy and detail), the last one having his tail pinched and rear end toasted by the flames, and exclaiming in monkey jabber sped up to chipmunk pitch. Meanwhile, Tillie is having her own troubles, as the fire has taken over her home, forcing her to climb above it on the central trunk extension through the roof of her treetop hut. The flames attempt to follow, climbing behind her. One licks at her tail, and Tillie bats a swing at it to drive it back, yelling, “Fresh!”

This scene is disrupted by the sound of shouts, bells, and sirens – and the aroma of smoke, picked up by the nose of the giraffe high above in the air. “Must be a fire somewhere”, he remarks. Yes, indeed – at Tillie’s house! From undisclosed causes, a blaze is attacking the bamboo treehouse high above the partygoers, and they watch helplessly from around the base of the tree, while Tillie attempts to beat back the advance of the flames alone, batting at them with a broom. A local fire department bravely answers the call, consisting of dozens of monkeys on a mile-long hook and ladder, and a chief riding in a separate wagon pulled by an ostrich (whom he has to prod from burying head in the sand by spritzing the bird with a seltzer bottle). Just before the fire company arrives, Tillie prepares to jump into a makeshift net carried by her party guests. But the flame transforms into a hand to grab her back by the tail, then divides into little flames that jump from the treehouse balcony onto the net below, burning it from the center outwards and scattering the party guests. The monkeys arrive and raise the rickety extension latter, scrambling up it one after another. The flame responds by jumping onto the ladder from the top, and following it down, setting it ablaze. The monkeys pull a fast 180 degree turn, and scramble back down the ladder in terror (animated with marvelous energy and detail), the last one having his tail pinched and rear end toasted by the flames, and exclaiming in monkey jabber sped up to chipmunk pitch. Meanwhile, Tillie is having her own troubles, as the fire has taken over her home, forcing her to climb above it on the central trunk extension through the roof of her treetop hut. The flames attempt to follow, climbing behind her. One licks at her tail, and Tillie bats a swing at it to drive it back, yelling, “Fresh!”

Back in the jungle, Elmer, who has climbed up the giraffe’s neck to get a view of what is happening, reacts in shock, and slides to the ground, breaking into a gallop to come to the rescue. The giraffe realizes he can be of help in getting Elmer to the fire quicker, and takes off after him at a brisk trot, scooping up Elmer on his head. In a clever shot, when Elmer finds himself suddenly high in the air instead of running, he still attempts to demonstrate he is giving his all to be the hero, by resuming the bobbing rhythm of his running gallop, despite not having his feet on the ground. The three pelicans also tag along, and the five-head force arrives at the scene of the chaos. Being atop the giraffe’s head gives Elmer a distinct height advantage, putting him nearly parallel with the level of the blaze, and also allows him to act as “head man” in the role of a de facto chief over his company’s operations. At a signal, the three pelicans are sent to an extension of the jungle stream, acting as water-scooping aircraft to carry liquid ammunition to Elmer inside their beaks. Elmer inserts his trunk into their reservoirs, taking a deep inhale, then focuses his aim upon Tillie’s hut. With a mighty blast, Elmer shoots a spray of water through the center of the nearly-consumed treehouse, putting out the fire on the main floor. (It should be noted that facial expressions of Elmer in his determined efforts to fight the fire bear a striking resemblance to those of Porky Pig in his round-eyed design exclusively used by Frank Tashlin at Warner Brothers, possibly suggesting that someone on this cartoon’s animation staff crossed paths with Tashlin’s unit at some point. An animator breakdown study of these shots might prove educational.) Elmer refills, and turns his attention to straggler flames in the roof thatching of the hut. Changing his hosing style to a series of short bursts, he takes precision aim at the individual flame-men, knocking them off one by one. A group of them flee up an angular brace toward the center trunk pole. Elmer bends his trunk into a snake-like curve, then fires a long jet of water. The water impossibly maintains the curving shape of Elmer’s trunk, and travels serpentine up the roof beam, extinguishing in one shot every flame on the pole. Elmer thinks his job is finished – but not so fast. “Elmer! Oh, Elmer!, Lookit!”, calls Tillie’s voice from far above. The tiger is pointing downwards to the trunk-pole upon which she clings. Four remaining flame men are tearing away bit by bit at a spot in the trunk just above the roof, reducing it to a narrow point, about ready to snap. Elmer returns to intermittent fore mode, taking careful aim at the fiery quartet. Three of the flames are unable to dodge, and easily knocked off. The last flame is much too clever, and hides behind the trunk pole, only periodically peeping its flame-head out fir a view, alternating from one side of the pole to the other. Elmer shifts aim back and forth to either side, but can’t catch the flame in one place long enough to draw a bead. The determined elephant employs a surprise strategy for a final master-shot, and reshapes his trunk into a large arc curve, extending halfway around his head. Like a pitcher about to throw his special curve ball (or the grasshopper in “Flowers For Madame”), Elmer gives it his all, and lets fly with a long jet of water. Again, the water maintains the curvature at which Elmer shoots it, making a complete u-turn loop around the backside of the trunk pole, to come up behind the lone flame and douse him out of existence. But the flames have done their work, and the eaten-away trunk begins to snap. Tillie lets out little screams of alarm as the pole trunk shudders and bends to almost a 45 degree angle, then breaks. But she does not fall, as the giraffe bends Elmer closer to the tree, and Elmer seizes the pole in the grip of his trunk, lifting Tillie with it away from the tree, and lowering them all with the giraffe’s neck back down to the ground, where Elmer plats the end of the pole into the dirt, so that Tillie can slide down to safety. The crowd cheers Elmer as a hero, everyone recognizing that is was his marvelous trunk that saves the day. Tillie attempts to reward her hero with a kiss – but that trunk gets in the way again. This time, Elmer is not going to settle for a mere smack on the beezer – so, he lifts his trunk high above Tillie’s head, curving it to pull Tillie closer to him, where she now has a clear path to his lips below. The two exchange an energetic lip-lock, which curls Tillie’s tail and knocks Elmer’s hat off, while Elmer maintains the privacy of the moment by extending one ear to hide the view from the camera.

Back in the jungle, Elmer, who has climbed up the giraffe’s neck to get a view of what is happening, reacts in shock, and slides to the ground, breaking into a gallop to come to the rescue. The giraffe realizes he can be of help in getting Elmer to the fire quicker, and takes off after him at a brisk trot, scooping up Elmer on his head. In a clever shot, when Elmer finds himself suddenly high in the air instead of running, he still attempts to demonstrate he is giving his all to be the hero, by resuming the bobbing rhythm of his running gallop, despite not having his feet on the ground. The three pelicans also tag along, and the five-head force arrives at the scene of the chaos. Being atop the giraffe’s head gives Elmer a distinct height advantage, putting him nearly parallel with the level of the blaze, and also allows him to act as “head man” in the role of a de facto chief over his company’s operations. At a signal, the three pelicans are sent to an extension of the jungle stream, acting as water-scooping aircraft to carry liquid ammunition to Elmer inside their beaks. Elmer inserts his trunk into their reservoirs, taking a deep inhale, then focuses his aim upon Tillie’s hut. With a mighty blast, Elmer shoots a spray of water through the center of the nearly-consumed treehouse, putting out the fire on the main floor. (It should be noted that facial expressions of Elmer in his determined efforts to fight the fire bear a striking resemblance to those of Porky Pig in his round-eyed design exclusively used by Frank Tashlin at Warner Brothers, possibly suggesting that someone on this cartoon’s animation staff crossed paths with Tashlin’s unit at some point. An animator breakdown study of these shots might prove educational.) Elmer refills, and turns his attention to straggler flames in the roof thatching of the hut. Changing his hosing style to a series of short bursts, he takes precision aim at the individual flame-men, knocking them off one by one. A group of them flee up an angular brace toward the center trunk pole. Elmer bends his trunk into a snake-like curve, then fires a long jet of water. The water impossibly maintains the curving shape of Elmer’s trunk, and travels serpentine up the roof beam, extinguishing in one shot every flame on the pole. Elmer thinks his job is finished – but not so fast. “Elmer! Oh, Elmer!, Lookit!”, calls Tillie’s voice from far above. The tiger is pointing downwards to the trunk-pole upon which she clings. Four remaining flame men are tearing away bit by bit at a spot in the trunk just above the roof, reducing it to a narrow point, about ready to snap. Elmer returns to intermittent fore mode, taking careful aim at the fiery quartet. Three of the flames are unable to dodge, and easily knocked off. The last flame is much too clever, and hides behind the trunk pole, only periodically peeping its flame-head out fir a view, alternating from one side of the pole to the other. Elmer shifts aim back and forth to either side, but can’t catch the flame in one place long enough to draw a bead. The determined elephant employs a surprise strategy for a final master-shot, and reshapes his trunk into a large arc curve, extending halfway around his head. Like a pitcher about to throw his special curve ball (or the grasshopper in “Flowers For Madame”), Elmer gives it his all, and lets fly with a long jet of water. Again, the water maintains the curvature at which Elmer shoots it, making a complete u-turn loop around the backside of the trunk pole, to come up behind the lone flame and douse him out of existence. But the flames have done their work, and the eaten-away trunk begins to snap. Tillie lets out little screams of alarm as the pole trunk shudders and bends to almost a 45 degree angle, then breaks. But she does not fall, as the giraffe bends Elmer closer to the tree, and Elmer seizes the pole in the grip of his trunk, lifting Tillie with it away from the tree, and lowering them all with the giraffe’s neck back down to the ground, where Elmer plats the end of the pole into the dirt, so that Tillie can slide down to safety. The crowd cheers Elmer as a hero, everyone recognizing that is was his marvelous trunk that saves the day. Tillie attempts to reward her hero with a kiss – but that trunk gets in the way again. This time, Elmer is not going to settle for a mere smack on the beezer – so, he lifts his trunk high above Tillie’s head, curving it to pull Tillie closer to him, where she now has a clear path to his lips below. The two exchange an energetic lip-lock, which curls Tillie’s tail and knocks Elmer’s hat off, while Elmer maintains the privacy of the moment by extending one ear to hide the view from the camera.

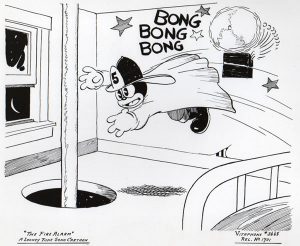

The Fire Alarm (Warner, Looney Tunes, 3/9/36 – Jack King, dir.) – As discussed in previous posts on this website, the landmark Merrie Melodies film “I Haven’t Got a Hat”, was the launching ground for a menagerie of “Our Gang” style characters whom Warner hoped to develop into stars in their own series, among them the sole breakout character being Porky Pig. Not to say tat Warner didn’t give the other cast members their respective opportunities to shine. Beans the Cat (originally intended as a partner for Porky – Porky and Beans, get it?) was the most featured of the others in his own shorts, but remained largely bland and unmemorable – another “Mickey Mouse” knock-off without notable personality traits, that always left writers in a corner, wondering what to do with him. Receiving less attention in their own right were a pair of troublesome puppies named Ham and Ex. (What’s with all these food gags? Was someone hungry at the original film’s story session?) The pops would appear in three combination appearances with Beans, the others being “The Phantom Ship” and “Westward Whoa”. The cartoon now under review marks the only tome they received screen credit to the exclusion of Beans on the title card, despite Beans’ presence in the picture.

The Fire Alarm (Warner, Looney Tunes, 3/9/36 – Jack King, dir.) – As discussed in previous posts on this website, the landmark Merrie Melodies film “I Haven’t Got a Hat”, was the launching ground for a menagerie of “Our Gang” style characters whom Warner hoped to develop into stars in their own series, among them the sole breakout character being Porky Pig. Not to say tat Warner didn’t give the other cast members their respective opportunities to shine. Beans the Cat (originally intended as a partner for Porky – Porky and Beans, get it?) was the most featured of the others in his own shorts, but remained largely bland and unmemorable – another “Mickey Mouse” knock-off without notable personality traits, that always left writers in a corner, wondering what to do with him. Receiving less attention in their own right were a pair of troublesome puppies named Ham and Ex. (What’s with all these food gags? Was someone hungry at the original film’s story session?) The pops would appear in three combination appearances with Beans, the others being “The Phantom Ship” and “Westward Whoa”. The cartoon now under review marks the only tome they received screen credit to the exclusion of Beans on the title card, despite Beans’ presence in the picture.

At a fire station, Chief Beans is surprised by a visit from the pups, carrying a note asking “Uncle Beans” to watch them for the day, signed by a mysterious “Lizzie”. (This is confusing. Since both the note and the kids call Beans their “Uncle”, is Lizzie the kids’ sister or mother? And considering that Ham and Ex are dogs, are they only half nephews-in-law through a mixed marriage between a dog and cat? Oh, well, if Flip the Frog could have a thing about cats in his fire epic previously reviewed…) Beans lets the kids in, but begins to regret it immediately, as the kids, boundless in energy, begin racing around the station uncontrollably – more than Beans can handle while trying to perform his duties of maintaining the fire equipment. The first thing the kids spot is a spare fire chief hat within the station. Both of them want to try it on, and wind up in a tug of war over it. One loses his grip, falling backwards, and comes up with his head caught in a fireman’s boot instead. The boot changes position as one brother pulls it off, only to get it caught upon his own brow, Finally, the battling results in the chief’s hat being torn in two, with one brother wearing the upper portion with the number shield, while the second wears only the brim – leaving both kids satisfied. They then turn their attention to other equipment. One of them climbs on board the hook and ladder truck, grabbing up the hose and nozzle and dragging it around the engine while the hose unspools. Before you know it, he has tied the engine up in a spider web of canvas. The second brother spots a switch on the side of the engine for “hose rewind”, and throws it into operation. The first brother is dragged backward at high speed through the entire maze of hose he has created, then spun around the winding spool several times before being thrown off the hook and ladder into the boiler stack of the pumper engine, coming out a hatch in the boiler’s side, right into the face of Beans. His sibling joins them a second later, stepping on a sponge Beans was using to clean the floor, dousing both Beans and his bother in soapy water. Beans can see he has two real troublemakers on his hands, and drags the twins to a bench against the wall, seating them there with order to be “QUIET!” As Beans walks away, the two dogs give him the raspberry from behind his back.

At a fire station, Chief Beans is surprised by a visit from the pups, carrying a note asking “Uncle Beans” to watch them for the day, signed by a mysterious “Lizzie”. (This is confusing. Since both the note and the kids call Beans their “Uncle”, is Lizzie the kids’ sister or mother? And considering that Ham and Ex are dogs, are they only half nephews-in-law through a mixed marriage between a dog and cat? Oh, well, if Flip the Frog could have a thing about cats in his fire epic previously reviewed…) Beans lets the kids in, but begins to regret it immediately, as the kids, boundless in energy, begin racing around the station uncontrollably – more than Beans can handle while trying to perform his duties of maintaining the fire equipment. The first thing the kids spot is a spare fire chief hat within the station. Both of them want to try it on, and wind up in a tug of war over it. One loses his grip, falling backwards, and comes up with his head caught in a fireman’s boot instead. The boot changes position as one brother pulls it off, only to get it caught upon his own brow, Finally, the battling results in the chief’s hat being torn in two, with one brother wearing the upper portion with the number shield, while the second wears only the brim – leaving both kids satisfied. They then turn their attention to other equipment. One of them climbs on board the hook and ladder truck, grabbing up the hose and nozzle and dragging it around the engine while the hose unspools. Before you know it, he has tied the engine up in a spider web of canvas. The second brother spots a switch on the side of the engine for “hose rewind”, and throws it into operation. The first brother is dragged backward at high speed through the entire maze of hose he has created, then spun around the winding spool several times before being thrown off the hook and ladder into the boiler stack of the pumper engine, coming out a hatch in the boiler’s side, right into the face of Beans. His sibling joins them a second later, stepping on a sponge Beans was using to clean the floor, dousing both Beans and his bother in soapy water. Beans can see he has two real troublemakers on his hands, and drags the twins to a bench against the wall, seating them there with order to be “QUIET!” As Beans walks away, the two dogs give him the raspberry from behind his back.

Beans has chosen a bad place to set the siblings, as above them is a test button for activating the fire alarm. Curious hands can’t resist pushing a button, and the alarm is sounded before the kids quite know what they have done. Upstairs, Beans’ sleeping fire crew is alerted into action (one heavy sleeper having to be roused by the living suspenders of his own trousers). They climb aboard the engines and proceed off – without a clue where they are going. Ham and Ex delight in the unexpected action, and sing a song about loving to fool the firemen. A few minutes later, the crew and engines return, after figuring out that no one has an address for the blaze, and Beans gives the twins the fish-eye, deducing from the wall button what caused the bell-ringing. Though the kids play innocent, Beans hauls them upstairs, deposits them in two of the beds in the living quarters, and orders them to go to sleep. Again, the minute he is out of sight, the boys do anything but rest. They begin performing acrobatic jumps from one bed to another, then slide down the fire pole back to the ground floor. Mindless of Beans’ orders, they now decide to commandeer the hook and ladder truck, one brother driving, the oter manning the wheel to steer the ladder end of the conveyance. Beans turns to watch aghast as the truck zooms through a side wall of the station, out into the street. He follows outside, but cannot spot the truck – as it has already made a loop around the block, and comes up behind him. Beans races down the street with the truck in pursuit, only avoiding being run over by falling down an open manhole in the street. In a dimensional tracking shot ahead of the vehicle, we see the ladder-end of the truck being mis-steered by the brother in the rear, swaying all over the highway and knocking down lines of telephone poles on each side of the street. Soon, the ladder end of the truck is traveling sideways, with both brothers riding side by side, taking up the whole street. As the road shifts to a divided highway, the truck clips the top off of a hedgerow in the center divider, and upsets a statue mounted between the hedges. The truck careens through a residential lot, smashing fences and carving away the entire first floor of the structure, leaving only the roof hanging above from wires fastened to the telephone lines. Inside, the owner continues to speak on the telephone: “Hello, operator? I’ve been cut off.” Ham and Ex next encounter what looks like a dead ringer for Fontaine Fox’s Toonerville Trolley, complete with the Skipper at the driver’s controls. They turn the vehicle upside down as the engine plows through, leaving the trolley traveling along with its electrical antenna on the tracks, and its wheels on the power lines above. Finally, after a couple of loops, the boys steer the engine back into the station house, through the hole they created, and race upstairs back to their bunks. Continuity becomes questionable here, as Beans, who appeared to have plain view of them stealing the engine, seems to be fooled by finding them pretending to be asleep in their beds – or at least is satisfied to let well-enough alone if they’ll stay asleep – and begins to tiptoe out of the room. One of the dogs still can’t resist another opportunity for mischief, and hurls a fireman’s boot directly at Beans’ noggin. Beans finally grabs up the pups and administers a paddling on their rear ends – seemingly a small penalty for all the damage and trouble they have caused.