As summer intensifies and the temperature climbs, we may sometimes be inclined to let our imaginations wander to the fiery flames of either the sun or Hades – which ought to put us right in the mood for our present subject of fire extinguishment. (Were it only that easy to escape the effects of a blistering-hot day, through extinguishers or water hoses!).

Oswald Rabbit returns for his third appearance in this series, in an episode that, despite its title, nearly doesn’t deserve inclusion within the subject topic at all. The Fireman (Lantz/Universal, 12/7/31 – Walter Lantz/Bill Nolan, dir.), sees no sign of a fire whatsoever. In fact, Oswald himself appears entirely out of uniform, wearing no fireman’s gear. The only connection with the title is that somehow, Oswald and Ortensia are attending a firemen’s picnic in the park A group of firemen are depicted riding to the event on a hook and ladder truck, with Oswald and Ortensia sitting atop the far end of the ladder, extending out past the end of the engine. The ladder bobs so much, the two spend most of the ride getting whacked in the rear end by the ladder rungs, then fall off. Behind them, towed by a rope from the rear bumper of the engine, is a small wagon carrying a pair of skunks. (They must be refugees from frequent appearances in Farmer Al Falfa cartoons for another studio.) Oswald and Ortensia land, straddling the tow rope, and giggle as they are repeatedly “goosed” by knots in the rope dragged between their legs. The skunk wagon passes between their legs as well, but miraculously they do not receive the infamous spray so as to become publicly ostracized from the event. They run after the engine, passing the fallen ladder, which develops feet on the end of its poles and trots along behind them. The remainder of the film loses its way almost entirely, nearly abandoning both firemen and picnic themes, wasting its footage on the supposedly-funny antics of a little brat cat who looks like Wilbur straight out of a Harman-Ising Bosko. Only a few brief shots return to the picnic grounds, showing the firemen acting in a highly unprofessional manner, by imbibing an endless supply of free-flowing beer. (And prohibition had not yet been repealed!)

Oswald Rabbit returns for his third appearance in this series, in an episode that, despite its title, nearly doesn’t deserve inclusion within the subject topic at all. The Fireman (Lantz/Universal, 12/7/31 – Walter Lantz/Bill Nolan, dir.), sees no sign of a fire whatsoever. In fact, Oswald himself appears entirely out of uniform, wearing no fireman’s gear. The only connection with the title is that somehow, Oswald and Ortensia are attending a firemen’s picnic in the park A group of firemen are depicted riding to the event on a hook and ladder truck, with Oswald and Ortensia sitting atop the far end of the ladder, extending out past the end of the engine. The ladder bobs so much, the two spend most of the ride getting whacked in the rear end by the ladder rungs, then fall off. Behind them, towed by a rope from the rear bumper of the engine, is a small wagon carrying a pair of skunks. (They must be refugees from frequent appearances in Farmer Al Falfa cartoons for another studio.) Oswald and Ortensia land, straddling the tow rope, and giggle as they are repeatedly “goosed” by knots in the rope dragged between their legs. The skunk wagon passes between their legs as well, but miraculously they do not receive the infamous spray so as to become publicly ostracized from the event. They run after the engine, passing the fallen ladder, which develops feet on the end of its poles and trots along behind them. The remainder of the film loses its way almost entirely, nearly abandoning both firemen and picnic themes, wasting its footage on the supposedly-funny antics of a little brat cat who looks like Wilbur straight out of a Harman-Ising Bosko. Only a few brief shots return to the picnic grounds, showing the firemen acting in a highly unprofessional manner, by imbibing an endless supply of free-flowing beer. (And prohibition had not yet been repealed!)

The man behind the pen that fashioned Mickey Mouse gets his at-bat to tackle fire prevention in Flip the Frog’s Fire – Fire (MGM, 3/5/32 – Ub Iwerks, dir.). The scene opens upstairs in the fire house, where Flip, a horse, and an old-timer cat are gathered round a checkerboard, killing time. The horse is on the spot, as the cat kibbitzes in the horse’s corner on strategy, while Flip seems to have the game well in hand. The cat suggests a move that forgets Flip has just obtained a king in the top row, and sets up a series of jumps for Flip to clean the board. The horse, possibly for the first time of any character in an Iwerks cartoon, utters the uncensored word “Damn” – a bit of a shock the first time I saw the film at UCLA, until I discovered that Flip himself adopted the word as a regular part of his lexicon in subsequent films. It is notable that sound work on this film is rather primitive, as several opportunities for utterances and sound effects go by on the screen without a peep on the soundtrack – such as Flip going through the motions of onscreen laughter, unaccompanied by any voice work. The horse has had enough of the cat’s advice, and smashes the checkerboard over the cat’s head. The horse returns to the bedroom in a huff, and pulls an interesting variation on the taking off the horseshoes gag, by hanging up his shoes on a pole, pitching ringers as in the game of the same name. A buzzer sounds on a box on the wall, causing a fire-mouse to emerge from the box with a small hammer, ringing a hanging fire-bell for an alarm. All he gets from the now-sleeping firemen is Flip flinging at him the chamber pot from under the bed, smashing it upon him. The angered mouse hops down from the box, approaches the bed, and pulls a nearby lever in the floor, tipping the bed upwards at the head, to slide the horse and firemen out from under the covers and down a hole in the floor. By means of a slide ramp, all three are neatly deposited aboard the pumper engine (a motorized model, despite the presence in the company of a horse). They race down the street, attracting the attention of a constable on a bicycle, who pulls them over. “Where do you think you’re going. To a fire?”, he demands. Flip can’t figure whether to answer yes or no, and receives a speeding ticket – which the officer punches a hole in like a meal ticket. Flip retaliates by pitting the engine into high gear, covering the officer in black exhaust smoke.

The man behind the pen that fashioned Mickey Mouse gets his at-bat to tackle fire prevention in Flip the Frog’s Fire – Fire (MGM, 3/5/32 – Ub Iwerks, dir.). The scene opens upstairs in the fire house, where Flip, a horse, and an old-timer cat are gathered round a checkerboard, killing time. The horse is on the spot, as the cat kibbitzes in the horse’s corner on strategy, while Flip seems to have the game well in hand. The cat suggests a move that forgets Flip has just obtained a king in the top row, and sets up a series of jumps for Flip to clean the board. The horse, possibly for the first time of any character in an Iwerks cartoon, utters the uncensored word “Damn” – a bit of a shock the first time I saw the film at UCLA, until I discovered that Flip himself adopted the word as a regular part of his lexicon in subsequent films. It is notable that sound work on this film is rather primitive, as several opportunities for utterances and sound effects go by on the screen without a peep on the soundtrack – such as Flip going through the motions of onscreen laughter, unaccompanied by any voice work. The horse has had enough of the cat’s advice, and smashes the checkerboard over the cat’s head. The horse returns to the bedroom in a huff, and pulls an interesting variation on the taking off the horseshoes gag, by hanging up his shoes on a pole, pitching ringers as in the game of the same name. A buzzer sounds on a box on the wall, causing a fire-mouse to emerge from the box with a small hammer, ringing a hanging fire-bell for an alarm. All he gets from the now-sleeping firemen is Flip flinging at him the chamber pot from under the bed, smashing it upon him. The angered mouse hops down from the box, approaches the bed, and pulls a nearby lever in the floor, tipping the bed upwards at the head, to slide the horse and firemen out from under the covers and down a hole in the floor. By means of a slide ramp, all three are neatly deposited aboard the pumper engine (a motorized model, despite the presence in the company of a horse). They race down the street, attracting the attention of a constable on a bicycle, who pulls them over. “Where do you think you’re going. To a fire?”, he demands. Flip can’t figure whether to answer yes or no, and receives a speeding ticket – which the officer punches a hole in like a meal ticket. Flip retaliates by pitting the engine into high gear, covering the officer in black exhaust smoke.

The engine arrives at the fire, and although the silhouettes of onlookers are seen in the foreground cheering, once again no voices are heard on the track. The cat hooks up the hose to a hydrant. Flip runs into the shot, and appears to pick up the other end of the hose, carrying it toward the blaze. His progress is abruptly halted, as he is yanked backward, because the hose won’t reach. Small wonder, because what he’s grabbed is not a hose at all, but the trunk of an elephant among the spectators, who angrily douses him with water from her schnozzola. Flip finally picks up the right hose, applying water with such high pressure that the building bends in rubbery fashion from the water’s impact. The pressure dies, however, and Flip discovers the horse sitting on the hose’s other end, trying to plug a leak that has developed. A misstep knocks the whole hydrant off its mounting, removing hope of a water attack upon the blaze. Suddenly, a female call for help is heard from an attractive cat on the top floor. Flip raises a ladder to the building, and begins climbing to the top. Along the way, however, he keeps encountering other animals in windows who want rescue. Flip only has eyes for the female prize above, and unceremoniously picks up each other tenant by the scruff of the neck, and drops them into free fall toward the ground. Below, his co-firemen try to position a net, but miss every tenant except the last – a fat pig, who goes right through the net and the sidewalk as well. Flip finally reaches the cat, but she is dragged back inside by a flame-man who strongly resembles Iwerks’ later creation of Old Man Winter in Jack Frost and Summertime. Flip enters the house in search of the cat, but encounters a black puffy smoke-man, who attempts to block his way. Like Indiana Jones, Flip pills out a revolver, and blasts the smoke-man in the breadbasket, causing him to fall over on his back deceased, rise transparently into the air, and disappear. Flip peers in the next room, where a quartet of flame-men are doing an Indian war dance around the fallen form of the cat. Flip confronts one of the flames, who turns on him and advances. Flip swings an axe at him, but only dissects him into two smaller versions of himself. Flip swings again, and now there are four of the fiery men. Flip shrugs his shoulders at the camera, as if to say “What are you gonna do?” Then Flip gets an idea, and grabs a nearby vacuum cleaner. Turning on the motor, he sucks three of the flame-men inside, leaving the fourth to be extinguished by a well-aimed spit from Flip. No explanation is provided for what happened to the other three flames, as Flip revives the girl, and, hearing the sound of louder crackling but no onscreen reappearance of the fire, Flip and the cat take off out the window, riding the vacuum like a witch’s flting broom (also with no explanation of how this is accomplished without an extension cord). The nozzle of the vacuum assumes living form, looking backwards at its riders, and accidentally swallows the cat. (Why doesn’t the cat meet the captured flames inside? Were they suffocated from lack of oxygen?) The vacuum coughs, spitting out the cat’s panties! Flip can’t resist this opportunity, and dives into the bag himself. Signs of a struggle are visible inside the bag canvas, and within a moment, Flip is booted back outside, with a lump on his head and black eyes, as the cat’s upper half appears in the mouth of the vacuum, wig-wagging a finger at him as if to say, “Naughty, naughty”, for the iris out.

The engine arrives at the fire, and although the silhouettes of onlookers are seen in the foreground cheering, once again no voices are heard on the track. The cat hooks up the hose to a hydrant. Flip runs into the shot, and appears to pick up the other end of the hose, carrying it toward the blaze. His progress is abruptly halted, as he is yanked backward, because the hose won’t reach. Small wonder, because what he’s grabbed is not a hose at all, but the trunk of an elephant among the spectators, who angrily douses him with water from her schnozzola. Flip finally picks up the right hose, applying water with such high pressure that the building bends in rubbery fashion from the water’s impact. The pressure dies, however, and Flip discovers the horse sitting on the hose’s other end, trying to plug a leak that has developed. A misstep knocks the whole hydrant off its mounting, removing hope of a water attack upon the blaze. Suddenly, a female call for help is heard from an attractive cat on the top floor. Flip raises a ladder to the building, and begins climbing to the top. Along the way, however, he keeps encountering other animals in windows who want rescue. Flip only has eyes for the female prize above, and unceremoniously picks up each other tenant by the scruff of the neck, and drops them into free fall toward the ground. Below, his co-firemen try to position a net, but miss every tenant except the last – a fat pig, who goes right through the net and the sidewalk as well. Flip finally reaches the cat, but she is dragged back inside by a flame-man who strongly resembles Iwerks’ later creation of Old Man Winter in Jack Frost and Summertime. Flip enters the house in search of the cat, but encounters a black puffy smoke-man, who attempts to block his way. Like Indiana Jones, Flip pills out a revolver, and blasts the smoke-man in the breadbasket, causing him to fall over on his back deceased, rise transparently into the air, and disappear. Flip peers in the next room, where a quartet of flame-men are doing an Indian war dance around the fallen form of the cat. Flip confronts one of the flames, who turns on him and advances. Flip swings an axe at him, but only dissects him into two smaller versions of himself. Flip swings again, and now there are four of the fiery men. Flip shrugs his shoulders at the camera, as if to say “What are you gonna do?” Then Flip gets an idea, and grabs a nearby vacuum cleaner. Turning on the motor, he sucks three of the flame-men inside, leaving the fourth to be extinguished by a well-aimed spit from Flip. No explanation is provided for what happened to the other three flames, as Flip revives the girl, and, hearing the sound of louder crackling but no onscreen reappearance of the fire, Flip and the cat take off out the window, riding the vacuum like a witch’s flting broom (also with no explanation of how this is accomplished without an extension cord). The nozzle of the vacuum assumes living form, looking backwards at its riders, and accidentally swallows the cat. (Why doesn’t the cat meet the captured flames inside? Were they suffocated from lack of oxygen?) The vacuum coughs, spitting out the cat’s panties! Flip can’t resist this opportunity, and dives into the bag himself. Signs of a struggle are visible inside the bag canvas, and within a moment, Flip is booted back outside, with a lump on his head and black eyes, as the cat’s upper half appears in the mouth of the vacuum, wig-wagging a finger at him as if to say, “Naughty, naughty”, for the iris out.

NOTE: Be sure to check out the storyboard reel from Fire Fire on Steve Stanchfield’s Thunderbean Thursday post.

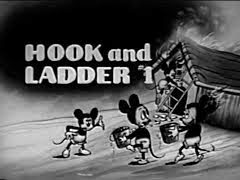

Hook and Ladder No. 1 (Terrytoons/Educational, 10/13/32 – Paul Terry/Bob Moser, dir.), possibly marks the first use of a land-based fire company in the sound-output of Terry’s newly-formed studio. However, knowing Terry’s habit of archiving old animation for reuse whenever possible, it would not be at all surprising if most of what we are seeing is someday determined to be a sound remake of the so-far undiscovered “Fire Fighters” from Van Buren in 1926. If so, this might present a question as to who was the first to personify flame – Aesop’s Fables, or Mutt and Jeff – as both productions appeared in the same year.

I recall first seeing this film from a Castle Films 16mm print on a rare day when my grammar school teacher decided to give us a little non-educational entertainment from a handful of old cartoons in a closet (also including Disney snippets from The Barnyard Battle, The Karnival Kid, and Orphan’s Picnic). At the time, I thought this film was the most primitive stone-age cartoon I had ever seen. Upon re-viewing, it’s not so bad by Terry standards, though the operatic-singing Oil Can Harry-style flame has stuck in my memory like a thorn for decades.

I recall first seeing this film from a Castle Films 16mm print on a rare day when my grammar school teacher decided to give us a little non-educational entertainment from a handful of old cartoons in a closet (also including Disney snippets from The Barnyard Battle, The Karnival Kid, and Orphan’s Picnic). At the time, I thought this film was the most primitive stone-age cartoon I had ever seen. Upon re-viewing, it’s not so bad by Terry standards, though the operatic-singing Oil Can Harry-style flame has stuck in my memory like a thorn for decades.

The film opens with a quartet of mouse fireman serenading through the hinged roof of the station house that they are the “Larchmont Volunteers” (an actual volunteer fire department, in which several Terry employees reputedly participated). In town (apparently in the Jewish district), a tall office building with retail clothing store on the ground floor named “Ginsberg’s” is on fire. A stereotypical Jewish character reports the blaze on a call box, which comes to life. “Ginsberg’s house is burning down”, says the man. “Oy yoy”, responds the call box. The alarm bell sounds at the station, and, in a scene archived for use, reuse – AND reuse, a repeating cycle of hook and ladder trucks, so long they have to make serpentine bends in their chassis to follow the road, snake their way to the fire. (This shot would still be in reuse as late as the mid-1940’s retraced for Technicolor.) Stealing the gag from Alice the Fire Fighter, the station house deflates to a flattened balloon as they exit. Stealing another Disney gag from “The Fire Fighters”, the engine siren is provided by twisting the tail of a yowling cat. In another shot that would be archived for reuse again and again, as the lead engine passes various homes, the cars of practically every person in town emerge from garages and driveways to follow the vehicle to the fire. (Reuses of this shot would for some reason generally flip the animation to run from right to left, as in The Banker’s Daughter (1933).) In an apartment separate from either the station house or the fire, a lone fire-mouse (possibly the chief?) still snoozes in bed, and is awakened by the sound of the sirens and bells outside the window. In a lengthy scene that seems to take up a quarter of the film, the mouse engages in the longest and most leisurely morning regimen imaginable, brushing his teeth, getting a shave, showering (also slipping in the bathtub), toweling off, morning exercises – and all this so he can get back into his nightshirt and go to sleep again, ignoring the fire entirely. Another shot modifies previous animation from an earlier film, depicting animals jumping out of windows of the burning building, who are mere modifictions of the “raining cats and dogs” gag from “Noah’s Outing” earlier in the same year. A crew of six mice tries to position a net under them, always missing. Someone throws out a kitchen stove from one of the windows, and its weight carries the firemen and net right through the pavement, into a hole so deep, they break a water main, filling the hole with a fountain of water.

The inconsistency of Terry continuity is evidenced by a scene where, despite the fire company being depicted up to now as all mice, a fire-cat appears from nowhere to check under the hood of the fire engine, revealing the engine’s sole power supply being a set of mice running atop the engine crankshaft. (Could be this was another old shot of reused animation, with the animators too lazy to remove the unexplained cat.) An oddball on-screen appearance is made by a caricature of an overweight human, carrying a satchel with the name “Herb Roth”. Roth was a local cartoonist/illustrator, also from Larchmont, who had achieved some fame with a series of humorous books, and whom Terry would turn to again in the 1940’s for a failed attempt to launch a Sunday comic strip for Mighty Mouse. Amid use of a Stanford University football cheer (Give him the axe, the axe…”), Herb chops up some furniture being brought out of the building, then bows to the crowd, losing his pants. The final sequence predicts the first appearance of Oil Can Harry and Fannie Zilch by a full year, with dialogue all sung un operatic form between a sweet young mouse heroine and the personified fire, who pursues her in almost dance step through the burning building, singing a number titled “They call me the Flame.” This was where, as a kid, I start to call out something like “Oh, brother”, or “P.U.” – how deranged and cornball can you get? She calls for help to the brigade below, and a hero mouse rises to the rescue by chopping away a fire hydrant, and riding its spout of water two thirds of the way up the building (all for no apparent reason, as the fire ladder is immediately raised to him, and he uses it to climb up the rest of the way). He carries the girl out the window onto the ladder, but mught as well have not used the ladder at all, as his jump breaks right through every rung, parting the ladder down the middle. Oh, well, the girl is safe, and she proposes marriage in song as the film irises out, to modified strains of the Wedding March.

The inconsistency of Terry continuity is evidenced by a scene where, despite the fire company being depicted up to now as all mice, a fire-cat appears from nowhere to check under the hood of the fire engine, revealing the engine’s sole power supply being a set of mice running atop the engine crankshaft. (Could be this was another old shot of reused animation, with the animators too lazy to remove the unexplained cat.) An oddball on-screen appearance is made by a caricature of an overweight human, carrying a satchel with the name “Herb Roth”. Roth was a local cartoonist/illustrator, also from Larchmont, who had achieved some fame with a series of humorous books, and whom Terry would turn to again in the 1940’s for a failed attempt to launch a Sunday comic strip for Mighty Mouse. Amid use of a Stanford University football cheer (Give him the axe, the axe…”), Herb chops up some furniture being brought out of the building, then bows to the crowd, losing his pants. The final sequence predicts the first appearance of Oil Can Harry and Fannie Zilch by a full year, with dialogue all sung un operatic form between a sweet young mouse heroine and the personified fire, who pursues her in almost dance step through the burning building, singing a number titled “They call me the Flame.” This was where, as a kid, I start to call out something like “Oh, brother”, or “P.U.” – how deranged and cornball can you get? She calls for help to the brigade below, and a hero mouse rises to the rescue by chopping away a fire hydrant, and riding its spout of water two thirds of the way up the building (all for no apparent reason, as the fire ladder is immediately raised to him, and he uses it to climb up the rest of the way). He carries the girl out the window onto the ladder, but mught as well have not used the ladder at all, as his jump breaks right through every rung, parting the ladder down the middle. Oh, well, the girl is safe, and she proposes marriage in song as the film irises out, to modified strains of the Wedding March.

Sleepy Time Down South (Fleischer/Paramount, Screen Songs, 11/11/32 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Bernard Wolf, anim. – featuring the Boswell Sisters), sounds like an unlikely title for a fire-fighting cartoon, but proves to be one nonetheless. (One would have supposed Fleischer would have targeted this plot for “A Hot Time In the Old Town Tonight” – in fact, he has the fire chief cat make verbal reference to such song title when heading to the fire.) The film opens as the chief awakens to an alarm bell, pounded out by a bird from a wall alarm box, upon a hapless alarm bell, who gets such a headache he has to protect himself with a small pillow from further blows. The chief tells the caller not to let the fire go out until they get there. He then awakens his crew by pulling a rope, causing all of their beds to fold into the wall, Murphy-style, dumping their occupants out chute openings at the base of the wall. The men race to a set of teeter-totters, jumping onto one end to flip a fireman’s helmet upon their heads from the other end. One small cat is too puny in weight to flip his teeter-totter, so has to recruit the extra weight of his shadow to join him in a jump, the hat flipping to cover the both of them. The crew pile on the sides of the hook and ladder truck, while the chief takes the wheel and pulls out – the wagon slipping neatly out from between the crew members, to dump them onto the ground. At the scene of the fire, the flames are through the roof of a multi-story apartment house. The building and its roof leap out of the flames, reassembling themselves nearby, to leave the flames in the shape of the structure but burning nothing. The flame gradually breaks into multiple “men”, who slip back into the apartment house under the door, filling up the building again in its new location. The fire chief, despite being a cat himself, uses the old yowling-cat alarm gag again from Mickey Mouse’s “The Fire Fighters.” The Boswell Sisters appear as three look-alike Betty Boops with modified hairdos in an upper window, singing the word “Help” repeatedly in three-part harmony. As the firemen hold a net below, the sisters dump out the window their upright piano, then jump themselves. The net crew misses both girls and instrument, but the sisters take things in stride and reassemble their piano in a garden corner to perform their number for the bouncing ball, transforming from animated to live-action form. (The animation is interestingly deceptive, depicting all three sisters walking – despite the fact that in real life, lead singer Connee Boswell was stricken with polio, making her unable to walk, so that during performance she always appeared in a seated position. Film producers used various means to mask this disability, and Fleischer’s use of walking animation is about as clever a means of such subterfuge as could be managed.)

Sleepy Time Down South (Fleischer/Paramount, Screen Songs, 11/11/32 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Bernard Wolf, anim. – featuring the Boswell Sisters), sounds like an unlikely title for a fire-fighting cartoon, but proves to be one nonetheless. (One would have supposed Fleischer would have targeted this plot for “A Hot Time In the Old Town Tonight” – in fact, he has the fire chief cat make verbal reference to such song title when heading to the fire.) The film opens as the chief awakens to an alarm bell, pounded out by a bird from a wall alarm box, upon a hapless alarm bell, who gets such a headache he has to protect himself with a small pillow from further blows. The chief tells the caller not to let the fire go out until they get there. He then awakens his crew by pulling a rope, causing all of their beds to fold into the wall, Murphy-style, dumping their occupants out chute openings at the base of the wall. The men race to a set of teeter-totters, jumping onto one end to flip a fireman’s helmet upon their heads from the other end. One small cat is too puny in weight to flip his teeter-totter, so has to recruit the extra weight of his shadow to join him in a jump, the hat flipping to cover the both of them. The crew pile on the sides of the hook and ladder truck, while the chief takes the wheel and pulls out – the wagon slipping neatly out from between the crew members, to dump them onto the ground. At the scene of the fire, the flames are through the roof of a multi-story apartment house. The building and its roof leap out of the flames, reassembling themselves nearby, to leave the flames in the shape of the structure but burning nothing. The flame gradually breaks into multiple “men”, who slip back into the apartment house under the door, filling up the building again in its new location. The fire chief, despite being a cat himself, uses the old yowling-cat alarm gag again from Mickey Mouse’s “The Fire Fighters.” The Boswell Sisters appear as three look-alike Betty Boops with modified hairdos in an upper window, singing the word “Help” repeatedly in three-part harmony. As the firemen hold a net below, the sisters dump out the window their upright piano, then jump themselves. The net crew misses both girls and instrument, but the sisters take things in stride and reassemble their piano in a garden corner to perform their number for the bouncing ball, transforming from animated to live-action form. (The animation is interestingly deceptive, depicting all three sisters walking – despite the fact that in real life, lead singer Connee Boswell was stricken with polio, making her unable to walk, so that during performance she always appeared in a seated position. Film producers used various means to mask this disability, and Fleischer’s use of walking animation is about as clever a means of such subterfuge as could be managed.)

When animation resumes, various gags with hoses are presented. The chief has a hose too short to reach, so drags the building towards himself a few feet to bring it into range. A second firefighter doesn’t bother with hoses and hydrants, using instead an elephant’s trunk, from which he pumps water as if from a well pump by raising and lowering the elephant’s tail. An impossible situation is presented by two more firemen, each of whom sprays water from a hose with nozzles on both ends – and no hydrant or other water source in the middle! A silly shot has a series of apartment tenants jumping out a window into a net, then climbing back into the burning building by means of a ladder, just so they can perform the same jump again and again. The Boswells provide voice over again, as three live flames lick the tail of the chief. He turns the hose on them, but they emerge unscathed, carrying umbrellas. The cat gives chase, back to the fire hydrant, where the three flames grow, and blow into the top of the hydrant. Suddenly, instead of water, flames are shooting out of the chief’s hose. The three fires pursue the chief down the street, while the emissions from his hose set every building on the block on fire, as the animation dissolves to a last shot of the Boswells, singing for the fade out.

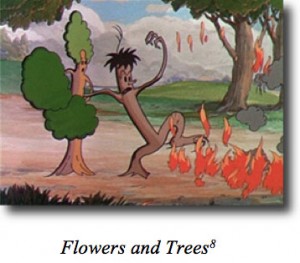

Though no actual firemen appear in the film, the creatures of the forest take a hand in extinguishing (and starting!) a wildfire, in the landmark Academy Award winner, Flowers and Trees (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony, 7/30/32 Burt Gillett, dir.). While it was actually not the first 3-strip Technicolor cartoon (Ted Esgbaugh’s unreleased The Wizard of Oz being the test film first commissioned), it was the first seen by the general public. In some respects, however, Disney was not quite ready to knock people’s socks off with rainbow hues. This is evident from the first, in the opening title card, which, instead of utilizing the bright yellow associated with the familiar sunburst opening of later Mickey Mouse cartoons, opts for a moderate middle-gold tone background, somewhat inoffensive to the eye, perhaps suggesting more the tints associated with Sepiatone and other tinting processes for black and white film that audiences of the time may have been more used to. Palette within the cartoon also attempts to stay true to nature, concentrating on middle greens and earth-tone browns. The Eshbaugh experiments in use of brighter vibrant paints would still have to wait a year or so, to suit Disney’s tastes in adjusting audiences to the new medium.

Though no actual firemen appear in the film, the creatures of the forest take a hand in extinguishing (and starting!) a wildfire, in the landmark Academy Award winner, Flowers and Trees (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony, 7/30/32 Burt Gillett, dir.). While it was actually not the first 3-strip Technicolor cartoon (Ted Esgbaugh’s unreleased The Wizard of Oz being the test film first commissioned), it was the first seen by the general public. In some respects, however, Disney was not quite ready to knock people’s socks off with rainbow hues. This is evident from the first, in the opening title card, which, instead of utilizing the bright yellow associated with the familiar sunburst opening of later Mickey Mouse cartoons, opts for a moderate middle-gold tone background, somewhat inoffensive to the eye, perhaps suggesting more the tints associated with Sepiatone and other tinting processes for black and white film that audiences of the time may have been more used to. Palette within the cartoon also attempts to stay true to nature, concentrating on middle greens and earth-tone browns. The Eshbaugh experiments in use of brighter vibrant paints would still have to wait a year or so, to suit Disney’s tastes in adjusting audiences to the new medium.

This unusual color choice actually leads to what amounts to a technical step backwards in the development of technique for flame animation. While Disney’s “The Fire Fighters” had achieved substantial effect by combining stark white flame against deep darkened backgrounds, no effort is made for lighting contrast to put across any sort of glow in this picture. In fact, though not overdone, a retreat to earlier drawing styles using a thin inked outline around the flame, rather than no outline, is used, further depriving the fire of any semblance of glow. Disney may have thought some outlining was necessary due to the somewhat more complex than usual layering of various waves of flame across the landscape as the fire spreads and grows in intensity, to distinguish one level of fire from another visibly. Then again, he may have felt the outlines were necessary because of the odd decision not to use a light base color for the body of the flame. Disney instead opts for a quite artificial-looking rich orange-red, with only slight touches of lighter yellow around its edges to simulate the flickering points of the blaze. This color separation may have necessitated outlining points so as to make it clear where the yellow should be painted in. Though no print has ever been displayed, lore has it that this film had already been completed or near-completed in black and white before the decision to convert it to color. It would have been of technical interest to see if the black and white version presented the fire sequence very differently, using the exposure and lighting techniques perfected in previous black and white efforts.

A very slight plot carries the film’s story-line. A cheerful morning has a young male sapling courting a sweet female tree with bowers of flowers in her foliage hair, until their romance is interrupted by a menacing, nearly-dead and decayed old tree stump, totally gray in color, with a protruding “tongue” out the hole in his trunk that serves as his mouth (actually a dark green lizard who lives inside). The old coot seizes and attempts to carry away the sweet young thing. (Forget about roots here, folks – these trees get around.) A duel commences between the boy and the stump, using fallen sticks as weapons. (Isn’t that the equivalent of humans dueling with skeleton arms?) The boy gains an advantage, by poking the stump in a knothole where a belly-button should be, inducing uncontrollable giggling, then pushing him backward and off-balance, to collapse upon the ground. A lily assumes him dead, and tries to plant itself upon his chest. But the villain slowly awakens, casting off the flower with disdain, and plots an alternative plan. If he can’t have the lady, no one can. So, he grabs up aother stick, and begins rubbing its point in rapid circles upon the side of a fallen log, in the manner of a boy scout, to start a fire. (Seedlings, don’t try this at home.). The blaze ignites and spreads quickly, blowing its way toward the boy and girl. Although able to walk before, out hero and heroine inexplicably stand their ground instead of running, with the boy attempting to stomp out the flames licking at his roots. (Also not recommended, when your feet themselves are flammable.) Other forest residents are affected, too. Bluebells begin ringing out an alarm. Overhead, an owl imitates the wail of a warning siren. (For once, a different species gets this duty – not a cat in sight.) Mushrooms reverse their growth spurts and shrink their way underground as the flames pass overhead. A pine tree assumes the shape of a mother hen, and ushers away smaller sprouts below her as if taking them under her wing. Daisies at the lakeside dip their petals in the water, then rotate like small fans to blows drops upon the approaching fire. A centipede retreats for a hole, dividing into segments to allow faster portions to push along slower portions of himself to safety. Another tree attempts escape at full run, but one of the flames jumps upon his lower trunk, causing the tree to leap out of its lower bark as if losing a pair of trousers. The tree jumps into the lake, where the hollow stump of another dead tree provides it with a new lower garment to cover its modesty. Meanwhile, the flames don’t play favorites. As the old stump who started it all rubs his limbs together in relishment of the apparent success of his plans, he fails to reckon with a new wave of fire sneaking up behind his back. An ember leaps upon him, then another. The helpless villain bats at the blaze in hopeless attempt to put out the burning spots on his person, merely allowing the fire to spread further over him as his limbs make contact with their intensity. (Again, how come this natural result happens to the villain, bit not the hero?) With the situation getting quite out of control, and the boy and girl almost surrounded, the forest birds decide to take matters into their own hands. One pair attempt an aerial water drop, by carrying their nest to the lake and attempting to fill it. The porous base ultimately retains no more than three drops to place upon the fire, and the flame vindictively reaches upwards and burns through the twigs and spindles of the construct, to leave it with a gaping hole. Fire rises ever skyward, attacking the roots of the entire forest (again excepting our star couple), and causing the birds to retreat to higher and higher limbs. Enough is enough – so the birds form a flock, and fly straight upwards to an elevated height, then reverse direction, and dive headfirst into a cloud, drilling it full of holes like a sieve, out of which pour abundant rain. The fire is extinguished just in time to save our romantic couple from harm. The last “hot spot” consists of one isolated “flame-man”, who runs to hide under a leaf, not realizing that the leaf has retained water from the rain in is curves above. The flame’s heat eats through the leaf surface above, releasing the water to douse the fire into extinction. As for the old stump, he lies motionless on his face, a charred remnant of himself, as two buzzards circle over him. (Wood-eating buzzards? Better not let termite control hear of this.) With the centipede curling up to serve as an engagement ring, the happy boy and girl pledge their betrothal, as the bluebells chime the Wedding March under a sky filled with a rainbow arc, for the iris out.

A very slight plot carries the film’s story-line. A cheerful morning has a young male sapling courting a sweet female tree with bowers of flowers in her foliage hair, until their romance is interrupted by a menacing, nearly-dead and decayed old tree stump, totally gray in color, with a protruding “tongue” out the hole in his trunk that serves as his mouth (actually a dark green lizard who lives inside). The old coot seizes and attempts to carry away the sweet young thing. (Forget about roots here, folks – these trees get around.) A duel commences between the boy and the stump, using fallen sticks as weapons. (Isn’t that the equivalent of humans dueling with skeleton arms?) The boy gains an advantage, by poking the stump in a knothole where a belly-button should be, inducing uncontrollable giggling, then pushing him backward and off-balance, to collapse upon the ground. A lily assumes him dead, and tries to plant itself upon his chest. But the villain slowly awakens, casting off the flower with disdain, and plots an alternative plan. If he can’t have the lady, no one can. So, he grabs up aother stick, and begins rubbing its point in rapid circles upon the side of a fallen log, in the manner of a boy scout, to start a fire. (Seedlings, don’t try this at home.). The blaze ignites and spreads quickly, blowing its way toward the boy and girl. Although able to walk before, out hero and heroine inexplicably stand their ground instead of running, with the boy attempting to stomp out the flames licking at his roots. (Also not recommended, when your feet themselves are flammable.) Other forest residents are affected, too. Bluebells begin ringing out an alarm. Overhead, an owl imitates the wail of a warning siren. (For once, a different species gets this duty – not a cat in sight.) Mushrooms reverse their growth spurts and shrink their way underground as the flames pass overhead. A pine tree assumes the shape of a mother hen, and ushers away smaller sprouts below her as if taking them under her wing. Daisies at the lakeside dip their petals in the water, then rotate like small fans to blows drops upon the approaching fire. A centipede retreats for a hole, dividing into segments to allow faster portions to push along slower portions of himself to safety. Another tree attempts escape at full run, but one of the flames jumps upon his lower trunk, causing the tree to leap out of its lower bark as if losing a pair of trousers. The tree jumps into the lake, where the hollow stump of another dead tree provides it with a new lower garment to cover its modesty. Meanwhile, the flames don’t play favorites. As the old stump who started it all rubs his limbs together in relishment of the apparent success of his plans, he fails to reckon with a new wave of fire sneaking up behind his back. An ember leaps upon him, then another. The helpless villain bats at the blaze in hopeless attempt to put out the burning spots on his person, merely allowing the fire to spread further over him as his limbs make contact with their intensity. (Again, how come this natural result happens to the villain, bit not the hero?) With the situation getting quite out of control, and the boy and girl almost surrounded, the forest birds decide to take matters into their own hands. One pair attempt an aerial water drop, by carrying their nest to the lake and attempting to fill it. The porous base ultimately retains no more than three drops to place upon the fire, and the flame vindictively reaches upwards and burns through the twigs and spindles of the construct, to leave it with a gaping hole. Fire rises ever skyward, attacking the roots of the entire forest (again excepting our star couple), and causing the birds to retreat to higher and higher limbs. Enough is enough – so the birds form a flock, and fly straight upwards to an elevated height, then reverse direction, and dive headfirst into a cloud, drilling it full of holes like a sieve, out of which pour abundant rain. The fire is extinguished just in time to save our romantic couple from harm. The last “hot spot” consists of one isolated “flame-man”, who runs to hide under a leaf, not realizing that the leaf has retained water from the rain in is curves above. The flame’s heat eats through the leaf surface above, releasing the water to douse the fire into extinction. As for the old stump, he lies motionless on his face, a charred remnant of himself, as two buzzards circle over him. (Wood-eating buzzards? Better not let termite control hear of this.) With the centipede curling up to serve as an engagement ring, the happy boy and girl pledge their betrothal, as the bluebells chime the Wedding March under a sky filled with a rainbow arc, for the iris out.

The Shanty Where Santy Claus Lives (Harman-Ising/Warner, Merrie Melodies, 1/7/33 – Hugh Harman/Rudolf Ising, dir.), is one of those traditional 1930’s toy-filled romps, as a waif receives the privilege of a visit to Santa’s toy shop at the north pole. Searching for a plot ending, the writers have a toy soldier jumping up and down upon a limb of Santa’s Christmas tree, causing a lit candle to topple off the branch, and set the tree on fire. (Hard to believe that this was once a traditional way of lighting up a tree before strings of electric bulbs, bringing to mind the Kurt Weill song “Jenny” from “Lady in the Dark”, where the subject character insists on lighting the candles herself as a child, and is “orphaned on Christmas day.” Surprising it didn’t happen that way in nearly every household.) Out of a “Toyland Fire Department” miniature station comes a wind-up hook and ladder truck with hose at the ready. Other dolls attempt to assist, one by jumping on the squeeze-bulb of a perfume atomizer filled with water, while another carries small buckets of water up to the tree by means of a mechanical conveyor ramp from a toy construction set. The guest-of-honor waif finds an item rather unusual to Santa’s supply of gifts – a full size bagpipe – placed conveniently near a kitchen sink. He solves the problem by filling the instrument with water, then playing a solo of “The Campbells are Coming” to squirt water out of the chanter and drones to quench the blaze, and save the day.

The Shanty Where Santy Claus Lives (Harman-Ising/Warner, Merrie Melodies, 1/7/33 – Hugh Harman/Rudolf Ising, dir.), is one of those traditional 1930’s toy-filled romps, as a waif receives the privilege of a visit to Santa’s toy shop at the north pole. Searching for a plot ending, the writers have a toy soldier jumping up and down upon a limb of Santa’s Christmas tree, causing a lit candle to topple off the branch, and set the tree on fire. (Hard to believe that this was once a traditional way of lighting up a tree before strings of electric bulbs, bringing to mind the Kurt Weill song “Jenny” from “Lady in the Dark”, where the subject character insists on lighting the candles herself as a child, and is “orphaned on Christmas day.” Surprising it didn’t happen that way in nearly every household.) Out of a “Toyland Fire Department” miniature station comes a wind-up hook and ladder truck with hose at the ready. Other dolls attempt to assist, one by jumping on the squeeze-bulb of a perfume atomizer filled with water, while another carries small buckets of water up to the tree by means of a mechanical conveyor ramp from a toy construction set. The guest-of-honor waif finds an item rather unusual to Santa’s supply of gifts – a full size bagpipe – placed conveniently near a kitchen sink. He solves the problem by filling the instrument with water, then playing a solo of “The Campbells are Coming” to squirt water out of the chanter and drones to quench the blaze, and save the day.

Oswald Rabbit makes up somewhat for his disappointing and off-point outing discussed above in Going to Blazes (Lantz/Universal, 4/10/33, Walter Lantz/Bill Nolan, dir.) – Another brat kid (this time a little dog?) struts his “tough guy” stuff along a street, when his eyes are affronted by the sight of a dog fireman (or perhaps we should say, fire-person, as his mannerisms and look call serious question to his gender) killing time in front of the station by dancing the most effeminate of ballet steps. The intolerant brat resorts to violence, by taking a swing at the firedog’s ankle with a fire axe. Instead, he cuts a gash in the station’s fire hose lying nearby, and the nozzle of the hose comes to life and whimpers like a wounded snake. The firedog calls for chief Oswald, who performs emergency surgery by stitching up the wound to put the hose back in shape, while the brat kid trues to duck out on the scene. Oswald catches the kid, and is about to administer a spanking, when the sound of a distant bell alerts him to a blaze in another tall apartment house. Oswald leaves the kid temporarily incapacitated, by hanging him by his outfit upon a nail protruding from a nearby fence. Oswald and the firedog return to the station, and emerge with a tiny wagon carrying hose and other equipment that serves as their only engine, with the firedog acting as its steed for power. Some power – as all the dog can do is more of his ballet dancing, while Oswald keeps time for him on the engine bell. The dog gets so caught up in his toe-dance that he doesn’t watch where he is going, and falls into an open manhole, while the engine rolls on over the opening. The dog tries to stop his fall by grabbing onto the end of the hose, unwinding it from its spool, then pilling the engine apart when the hose reaches its end. Oswald surveys the damage, and retrieves from the wreckage the structure of the winding spool (now resembling a sawhorse), a fire axe, and a “portable” hydrant and pail. Jamming the handle of the axe into one end of the winding spool to serve as a head, Oswald converts the two objects into a living horse, which carries him the rest of the way to the fire. Meanwhile, the kid wriggles off the fence nail, finds the same piece of hose he had injured earlier, and commands it to carry him to the fire. The hose begins to take hops like a lunging serpent, and provides the kid’s transportation to follow Oswald.

Oswald Rabbit makes up somewhat for his disappointing and off-point outing discussed above in Going to Blazes (Lantz/Universal, 4/10/33, Walter Lantz/Bill Nolan, dir.) – Another brat kid (this time a little dog?) struts his “tough guy” stuff along a street, when his eyes are affronted by the sight of a dog fireman (or perhaps we should say, fire-person, as his mannerisms and look call serious question to his gender) killing time in front of the station by dancing the most effeminate of ballet steps. The intolerant brat resorts to violence, by taking a swing at the firedog’s ankle with a fire axe. Instead, he cuts a gash in the station’s fire hose lying nearby, and the nozzle of the hose comes to life and whimpers like a wounded snake. The firedog calls for chief Oswald, who performs emergency surgery by stitching up the wound to put the hose back in shape, while the brat kid trues to duck out on the scene. Oswald catches the kid, and is about to administer a spanking, when the sound of a distant bell alerts him to a blaze in another tall apartment house. Oswald leaves the kid temporarily incapacitated, by hanging him by his outfit upon a nail protruding from a nearby fence. Oswald and the firedog return to the station, and emerge with a tiny wagon carrying hose and other equipment that serves as their only engine, with the firedog acting as its steed for power. Some power – as all the dog can do is more of his ballet dancing, while Oswald keeps time for him on the engine bell. The dog gets so caught up in his toe-dance that he doesn’t watch where he is going, and falls into an open manhole, while the engine rolls on over the opening. The dog tries to stop his fall by grabbing onto the end of the hose, unwinding it from its spool, then pilling the engine apart when the hose reaches its end. Oswald surveys the damage, and retrieves from the wreckage the structure of the winding spool (now resembling a sawhorse), a fire axe, and a “portable” hydrant and pail. Jamming the handle of the axe into one end of the winding spool to serve as a head, Oswald converts the two objects into a living horse, which carries him the rest of the way to the fire. Meanwhile, the kid wriggles off the fence nail, finds the same piece of hose he had injured earlier, and commands it to carry him to the fire. The hose begins to take hops like a lunging serpent, and provides the kid’s transportation to follow Oswald.

Another anthropomorphic flame is discovered in the window of the office building. Animation of the flame is amazingly inconsistent throughout the film, almost appearing to be two entirely different characters, likely explained by the division of work between Lantz and Nolan, who may not have even looked over their shoulders to see what the other was doing. One design is surprisingly square in shape, seemingly fashioned to custom-fit the widow frames out of which it peers. The other is a wildly-erratic, generally circular ball of fire, fluctuating greatly in size. My money’s bet on this wilder version being from the pencil of Nolan. When first seen, the blaze beats on its own chest in the manner of Tarzan, then shouts, “Whoopee!”, having a grand old time. Oswald turns to the task of obtaining water from his miraculous portable hydrant, which requires no hookup to any plumbing. A good gag deserves repeating – at least in a studio of restricted budget – and so a sequence is lifted near-verbatim from an earlier Oswald, “Hot Feet”, as Oswald opens the hydrant valve from the top, hoping to obtain a jet of water to fill his pail. Each time the valve is opened, the water gushes from the hose connection on the wrong side of the hydrant, drenching Oswald instead of the bucket. Ozzie solves the problem by slicing the bucket end-on with his fire axe into two halves (similar to teacups from Alice in Wonderland’s Mad Tea Party), and positioning each half opposite each of the hydrant nozzles. Now, the water comes out both sides, filling each half-bucket as if a parted half of the Red Sea – then Oswald simply puts the two halves together to amazingly heal the bucket up ike new, and proceed to the fire. All this for naught, as the brat kid arrives on the scene, tripping Oswald up with his hose section, and spilling all the water. Oswald grabs the hose, and connects it to the hydrant. He sprays a stream of water at the fire. The flame opens its mouth, takes the water in its cheeks, gargles with it, then spits it out to drench Oswald. Now the flame changes locations, climbing like a human fly along the outside of the building to reach the fifth floor. Jumping in the window, the flame sets about committing mischief – setting the beard afire of an old man in a wall portrait, and eating the blanket and tickling the feet of a sleeping pig.

Another anthropomorphic flame is discovered in the window of the office building. Animation of the flame is amazingly inconsistent throughout the film, almost appearing to be two entirely different characters, likely explained by the division of work between Lantz and Nolan, who may not have even looked over their shoulders to see what the other was doing. One design is surprisingly square in shape, seemingly fashioned to custom-fit the widow frames out of which it peers. The other is a wildly-erratic, generally circular ball of fire, fluctuating greatly in size. My money’s bet on this wilder version being from the pencil of Nolan. When first seen, the blaze beats on its own chest in the manner of Tarzan, then shouts, “Whoopee!”, having a grand old time. Oswald turns to the task of obtaining water from his miraculous portable hydrant, which requires no hookup to any plumbing. A good gag deserves repeating – at least in a studio of restricted budget – and so a sequence is lifted near-verbatim from an earlier Oswald, “Hot Feet”, as Oswald opens the hydrant valve from the top, hoping to obtain a jet of water to fill his pail. Each time the valve is opened, the water gushes from the hose connection on the wrong side of the hydrant, drenching Oswald instead of the bucket. Ozzie solves the problem by slicing the bucket end-on with his fire axe into two halves (similar to teacups from Alice in Wonderland’s Mad Tea Party), and positioning each half opposite each of the hydrant nozzles. Now, the water comes out both sides, filling each half-bucket as if a parted half of the Red Sea – then Oswald simply puts the two halves together to amazingly heal the bucket up ike new, and proceed to the fire. All this for naught, as the brat kid arrives on the scene, tripping Oswald up with his hose section, and spilling all the water. Oswald grabs the hose, and connects it to the hydrant. He sprays a stream of water at the fire. The flame opens its mouth, takes the water in its cheeks, gargles with it, then spits it out to drench Oswald. Now the flame changes locations, climbing like a human fly along the outside of the building to reach the fifth floor. Jumping in the window, the flame sets about committing mischief – setting the beard afire of an old man in a wall portrait, and eating the blanket and tickling the feet of a sleeping pig.

The startled pig leaps out the window, then looks down at the pavement to see there is no net below. Using his best swimming strokes, the pig defies gravity to swim back up to the window. While the flame laughs, the pig picks up his entire bed and tosses it out the window ahead of him, to provide a soft place for him to fall. The wily bed doesn’t relish the thought of someone that fat lading upon him, and double-crosses the pig by pulling itself out of the way as the pig hits the pavement. The flame next goes after a sweet damsel dog. Oswald tries to climb a nearby telephone pole to the height of the window, but can find no steps on the pole to climb on. He resourcefully extracts the horns off a cow bystander, and uses them on his feet as climbing spikes. Someone has rigged a clothesline from the pole over to the apartment window, and Oswald repeats the “Alice the Fire Fighter” gag of using a pair of panties as a breeches buoy to get over to the window. Inside, he confronts the threatening flame with a vacuum cleaner a la Flip the Frog, sucking it inside the bag. The flame isn’t confined for long, and burns through the bag, as Oswald and the girl try to make their escape in the panties. A variation on the Mickey Mouse “Fire Fighters” ending has the flame again burn the clothesline away. Oswald and the girl fall to a second clothesline below (why didn’t we see this line on Oswald’s way up?), falling into the pant legs of a pair of long-Johns, while the original panties remain caught on the clothesline above the garment. The brat kid finally does something right, climbing out on the clothesline to tickle the long-Johns at the underarm. The long-Johns lose their grip on the clothesline, but grab the panties, using them as parachute to bring Oswald and the girl in for a safe landing, and the end of the cartoon.

The startled pig leaps out the window, then looks down at the pavement to see there is no net below. Using his best swimming strokes, the pig defies gravity to swim back up to the window. While the flame laughs, the pig picks up his entire bed and tosses it out the window ahead of him, to provide a soft place for him to fall. The wily bed doesn’t relish the thought of someone that fat lading upon him, and double-crosses the pig by pulling itself out of the way as the pig hits the pavement. The flame next goes after a sweet damsel dog. Oswald tries to climb a nearby telephone pole to the height of the window, but can find no steps on the pole to climb on. He resourcefully extracts the horns off a cow bystander, and uses them on his feet as climbing spikes. Someone has rigged a clothesline from the pole over to the apartment window, and Oswald repeats the “Alice the Fire Fighter” gag of using a pair of panties as a breeches buoy to get over to the window. Inside, he confronts the threatening flame with a vacuum cleaner a la Flip the Frog, sucking it inside the bag. The flame isn’t confined for long, and burns through the bag, as Oswald and the girl try to make their escape in the panties. A variation on the Mickey Mouse “Fire Fighters” ending has the flame again burn the clothesline away. Oswald and the girl fall to a second clothesline below (why didn’t we see this line on Oswald’s way up?), falling into the pant legs of a pair of long-Johns, while the original panties remain caught on the clothesline above the garment. The brat kid finally does something right, climbing out on the clothesline to tickle the long-Johns at the underarm. The long-Johns lose their grip on the clothesline, but grab the panties, using them as parachute to bring Oswald and the girl in for a safe landing, and the end of the cartoon.

The False Alarm (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 4/22/33 – Dick Humour, dir.) is one of the more lively and fun installments of the series – and seems to have also been thought so by studio executives over time, as it was one of only two Scrappy’s which remained in print when Columbia established its own home movie distribution company circa the late 50’s or early 60’s. An old goat runs in panic out of his apartment house, which is fully enveloped in flame from its upper story windows. He runs to a call box, using an old-style alarm bell system, requiring the manual turning of a handle to send a telegraph-like signal to the alarm bell in the fire house. (Real life variants of this model can be seen in the early Our Gang comedies “Small Talk” and “Bargain Day”.) At the station, an alarm bell rings above the chair of Chief Scrappy, who is sound asleep. The clapper ringing the bell bends outward, re-aiming its blows upon Scrappy’s head to awaken him. Scrappy grabs his hat and a fire axe off the wall, then races to alert his crew, consisting of Oopie and an old horse, bunking in adjacent beds. Similar to “Sleepy Time Down South”, Scrappy pulls a rope, lifting the head of each bed up the side of the wall, and dumping out the occupants. Scrappy prods Oopie to the fire pole, as Oopie grabs his own hat and also a sort of spear or poker on a pole. Oopie descends the pole first, leaving the spear pointed in upwards position as he lands. Scrappy comes down, catching the pole in his pants leg, and tearing a large hole in his seat with the spear’s sharp end. The horse meanwhile has evaded coming down the pole with them, and gone back to bed again. Scrappy tells Oopie to go back upstairs and get the horse. Oopie hurries upstairs, begs and pleads with the horse, and tries to drag him out of the sack, to no avail. When Scrappy also hurries upstairs to see what is the holdup, he finds Oopie has given up, and is also asleep in the bed beside the horse. Scrappy manually tips the bed sideways, dumping the crew out again. Another slide downstairs, with the horse going first, Oopie next, then Scrappy – to repeat the same spear-in-the-pants gag for a second set of ripped trousers. Scrappy continues to follow his duty, succeeding in getting the horse hitched to the pumper engine. He opens the station doors, and tells curious onlookers outside to stand back. The sounds of siren and engine bell are heard from inside, leading the crowd to expect heroic action to ensue. Instead, the horse slowly plods out of the station at a snail’s pace, traveling no more than one mile per hour, despite the energetic work of Scrappy and Oopie in manning the siren and bell. Back at the fire scene, the goat tries desperately to rescue furniture by dragging and pushing various articles outside – only to have the flames reach out the upper-story windows, to drag each item of furniture back in. By the time Scrappy and Oopie arrive with the wagon, the building is reduced to a few sticks of smoldering rubble. “It’s too late”, cries the goat. Scrappy repeats the news to Oopie, and order the horse back to the station. While the horse refused to travel more than a step at a time on the outbound trip, news that he can return to his comfortable bed has the effect of rejuvenation upon him, allowing him to suddenly find the speed of the wind, arriving at the fire house in about three seconds flat, and plop into bed. Scrappy and Oopie are forced to follow on foot, quite ready to administer some discipline to the horse, as soon as they can catch up with him.

The False Alarm (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 4/22/33 – Dick Humour, dir.) is one of the more lively and fun installments of the series – and seems to have also been thought so by studio executives over time, as it was one of only two Scrappy’s which remained in print when Columbia established its own home movie distribution company circa the late 50’s or early 60’s. An old goat runs in panic out of his apartment house, which is fully enveloped in flame from its upper story windows. He runs to a call box, using an old-style alarm bell system, requiring the manual turning of a handle to send a telegraph-like signal to the alarm bell in the fire house. (Real life variants of this model can be seen in the early Our Gang comedies “Small Talk” and “Bargain Day”.) At the station, an alarm bell rings above the chair of Chief Scrappy, who is sound asleep. The clapper ringing the bell bends outward, re-aiming its blows upon Scrappy’s head to awaken him. Scrappy grabs his hat and a fire axe off the wall, then races to alert his crew, consisting of Oopie and an old horse, bunking in adjacent beds. Similar to “Sleepy Time Down South”, Scrappy pulls a rope, lifting the head of each bed up the side of the wall, and dumping out the occupants. Scrappy prods Oopie to the fire pole, as Oopie grabs his own hat and also a sort of spear or poker on a pole. Oopie descends the pole first, leaving the spear pointed in upwards position as he lands. Scrappy comes down, catching the pole in his pants leg, and tearing a large hole in his seat with the spear’s sharp end. The horse meanwhile has evaded coming down the pole with them, and gone back to bed again. Scrappy tells Oopie to go back upstairs and get the horse. Oopie hurries upstairs, begs and pleads with the horse, and tries to drag him out of the sack, to no avail. When Scrappy also hurries upstairs to see what is the holdup, he finds Oopie has given up, and is also asleep in the bed beside the horse. Scrappy manually tips the bed sideways, dumping the crew out again. Another slide downstairs, with the horse going first, Oopie next, then Scrappy – to repeat the same spear-in-the-pants gag for a second set of ripped trousers. Scrappy continues to follow his duty, succeeding in getting the horse hitched to the pumper engine. He opens the station doors, and tells curious onlookers outside to stand back. The sounds of siren and engine bell are heard from inside, leading the crowd to expect heroic action to ensue. Instead, the horse slowly plods out of the station at a snail’s pace, traveling no more than one mile per hour, despite the energetic work of Scrappy and Oopie in manning the siren and bell. Back at the fire scene, the goat tries desperately to rescue furniture by dragging and pushing various articles outside – only to have the flames reach out the upper-story windows, to drag each item of furniture back in. By the time Scrappy and Oopie arrive with the wagon, the building is reduced to a few sticks of smoldering rubble. “It’s too late”, cries the goat. Scrappy repeats the news to Oopie, and order the horse back to the station. While the horse refused to travel more than a step at a time on the outbound trip, news that he can return to his comfortable bed has the effect of rejuvenation upon him, allowing him to suddenly find the speed of the wind, arriving at the fire house in about three seconds flat, and plop into bed. Scrappy and Oopie are forced to follow on foot, quite ready to administer some discipline to the horse, as soon as they can catch up with him.

No sooner do the boys set foot in the station, than another alarm bell is heard. Here we go again. But Scrappy is determined not to let this trip be a repeat performance of the last one. He and Oopie grab an extinguisher canister with a pointed nozzle tip off the wall, and race to the horse’s bunk. In the manner that crooked jockeys would dope their horses with “speed” injections, Scrappy and Oopie convert the extinguisher into a hypodermic needle, injecting the horse painfully in the rear end, causing him instantly to spring to life, ready to set a new land record in getting to the new fire. Down the fire pole the trio goes again. This time, Oopie has positioned the engine close to the pole – too close for Scrappy’s tastes, as he lands in the vent hole of the engine boiler, still alight with heat from the previous ride, and burning Scrappy’s rear end painfully. Oopie hastily harnesses the horse to the engine, not noticing that he has hooked the straps around both sides of the fire pole to reach the horse. “Giddap”, shouts Scrappy – but the horse and engine are tethered to the pole, bending it to its structural limit, until the harness breaks, snapping the engine backwards and into the wall. Scrappy grabs the horse by the collar and drags him over to the engine, rehitching his harness. This time, in his haste, he hooks the horse in backwards, facing the wrong way. Instead of pulling, the horse pushes the wagon, straight into the wall again. Scrappy solves his harnessing error by yanking the horse’s head off one end of his body, and reinserting it in the other end, changing the horse’s direction impossibly but time-efficiently. Finally, the wagon races out of the station in respectable fashion. It looks like the boys will finally make it to a blaze on time – until they arrive at the source of the alarm, to find no fire in sight. Instead, two birds have taken position upon either end of the turning handle upon the local call box, and are bobbing up and down upon the handle in a playful game of see-saw, ringing the alarm bell for nothing all the while. Scrappy’s horse catches on, and gives the boys a resounding horse-laugh, then kicks at the engine to release himself (leaving the engine boiler a battered, fiery mess), and again races back to the fire station. Scrappy and Oopie briefly wrestle with a water pump in vain attempt to rescue the engine, but accomplish nothing. It is a total loss. The duo again races back to the station, and an angry Scrappy is about to raise his axe to chop at the horse to teach him a lesson – when the fire alarm rings for the third time. Wise Scrappy re-routes the direction of his anger – and hacks away at the alarm box with his axe, removing the real source of their troubles once and for all. Both boys climb in with the horse to get a peaceful and undisturbed night’s sleep. Or so they wish, as a ringing is again heard, despite the broken fire bell still lying disassembled on the floor off to one side of the bed. Scrappy investigates, and finds the clapper of the alarm, still wired to the electrical current, hammering away at a chamber pot under the bed. Scrappy gives a look of frustrated exasperation to the camera, as we iris out.

No sooner do the boys set foot in the station, than another alarm bell is heard. Here we go again. But Scrappy is determined not to let this trip be a repeat performance of the last one. He and Oopie grab an extinguisher canister with a pointed nozzle tip off the wall, and race to the horse’s bunk. In the manner that crooked jockeys would dope their horses with “speed” injections, Scrappy and Oopie convert the extinguisher into a hypodermic needle, injecting the horse painfully in the rear end, causing him instantly to spring to life, ready to set a new land record in getting to the new fire. Down the fire pole the trio goes again. This time, Oopie has positioned the engine close to the pole – too close for Scrappy’s tastes, as he lands in the vent hole of the engine boiler, still alight with heat from the previous ride, and burning Scrappy’s rear end painfully. Oopie hastily harnesses the horse to the engine, not noticing that he has hooked the straps around both sides of the fire pole to reach the horse. “Giddap”, shouts Scrappy – but the horse and engine are tethered to the pole, bending it to its structural limit, until the harness breaks, snapping the engine backwards and into the wall. Scrappy grabs the horse by the collar and drags him over to the engine, rehitching his harness. This time, in his haste, he hooks the horse in backwards, facing the wrong way. Instead of pulling, the horse pushes the wagon, straight into the wall again. Scrappy solves his harnessing error by yanking the horse’s head off one end of his body, and reinserting it in the other end, changing the horse’s direction impossibly but time-efficiently. Finally, the wagon races out of the station in respectable fashion. It looks like the boys will finally make it to a blaze on time – until they arrive at the source of the alarm, to find no fire in sight. Instead, two birds have taken position upon either end of the turning handle upon the local call box, and are bobbing up and down upon the handle in a playful game of see-saw, ringing the alarm bell for nothing all the while. Scrappy’s horse catches on, and gives the boys a resounding horse-laugh, then kicks at the engine to release himself (leaving the engine boiler a battered, fiery mess), and again races back to the fire station. Scrappy and Oopie briefly wrestle with a water pump in vain attempt to rescue the engine, but accomplish nothing. It is a total loss. The duo again races back to the station, and an angry Scrappy is about to raise his axe to chop at the horse to teach him a lesson – when the fire alarm rings for the third time. Wise Scrappy re-routes the direction of his anger – and hacks away at the alarm box with his axe, removing the real source of their troubles once and for all. Both boys climb in with the horse to get a peaceful and undisturbed night’s sleep. Or so they wish, as a ringing is again heard, despite the broken fire bell still lying disassembled on the floor off to one side of the bed. Scrappy investigates, and finds the clapper of the alarm, still wired to the electrical current, hammering away at a chamber pot under the bed. Scrappy gives a look of frustrated exasperation to the camera, as we iris out.

More hot and heavy adventures of the 30’s continue next week.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

“I can think of no more stirring symbol of man’s humanity to man than a fire engine.” — Kurt Vonnegut

Like Vonnegut, Paul Terry seems to have taken a great deal of pride in his service with a volunteer fire brigade, to judge by the number of cartoons his studio made on the subject. He and cartoonist Herb Roth were both members of the Larchmont Volunteers’ Hook and Ladder Company No. 1, as well as personal friends and next door neighbours in that affluent village; Terry had been best man at Roth’s wedding. At first I had the idea that Terry might have commissioned Phil Scheib to compose an anthem for the Larchmont Volunteers, and then used it in a cartoon to avoid having to pay the composer anything beyond salary. It’s the sort of thing Terry would do. But then I noticed that the song’s lyrics are rather tongue-in-cheek, not really appropriate for official ceremonies. Scheib himself lived in an apartment in New Rochelle — he couldn’t afford to live in Larchmont on what Paul Terry was paying him!

I have no idea whether there was really a Ginsberg’s clothing store in Larchmont or New Rochelle, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised.

I didn’t know that Connie Boswell was unable to walk. In those days people often went to great lengths to conceal disabilities, even minor ones. The barbershop quartet The Buffalo Bills, for example, carefully coordinated their hand gestures to avoid drawing attention to the fact that their high tenor, Vern Reed, was missing the ring finger on one of his hands.

Funny how Oswald’s a hero for saving the girl in the end, but he never actually puts out the fire….

Before “Flowers and Trees”, a forest fire was ignited and extinguished in an earlier Silly Symphony, “Playful Pan” (Disney/Columbia, 27/12/30 — Burt Gillett, dir.). Pan is the Greek god Pan, and he playfully plays, not a syrinx or panpipes (i.e., a set of tuned reeds without finger holes, arranged parallel to each other and bound together in a cluster), but an aulos, consisting of two pipes with finger holes joined at an angle from a single mouthpiece. Syrinx was a wood nymph who turned herself into a reed to avoid being pursued by Pan, whereupon Pan took to kissing every reed he could get his lips on, and in so doing he discovered that he could play music on them. The aulos, on the other hand, was associated with satyrs rather than Pan. In a famous myth, a satyr challenged Apollo to an aulos-playing contest, lost, and was skinned alive as punishment for his hubris. But I digress.

The cartoon opens with Pan playing his aulos in an Arcadian landscape, inspiring the fish, flowers, worms, trees, and even the clouds in the sky to dance to his music. But when two clouds attempt a prototypical version of the Hustle, their bumping buttocks emit a lightning bolt that saws vertically through a tree trunk, setting it alight. The fire quickly spreads through the forest as the woodland creatures flee in terror. (For what it’s worth, the flames have inked outlines.) The animals try to contain the blaze: rabbits kick dirt onto it, a skunk beats it with a tree branch, two beavers try to smother it with their tails, and a couple of raccoons take turns sucking up mouthfuls of water from a stream and spitting it on the flames — all to no avail. Finally a raccoon alerts Pan, who apparently has been blithely playing his aulos all this time, and the god springs into action.