A storm on screen may seem impressive, as the flash of lightning illuminates the theater seats and patrons, and the imagery is obscured by trails of raindrops or biting snow. But how much more effective it is when accompanied by a massed chorus of slide whistles, the beat of kettle drums, and the rattling of a large sheet of aluminum to simulate thunder. The films we discuss today may have been among the first in animation history to be accompanied by such effects. Some were certainly more sophisticated than others, while many continued to struggle just to figure what noises would fit on screen to keep the audience’s ears occupied enough to realize they were not merely viewing a silent scored by the local Bijou pianist. Some, such as Disney, would offer synchronization timed with mathematical precision, while others, such as Lantz and Van Buren, would make desperate stabs at recording tracks in one take, while staring at a screen already filled with an animated image waiting to find its voice. The differences in technique must have seemed jarring to audiences of the day, and it is no wonder that Disney’s product rose to be regarded as masterpieces, while so many others’ work lapsed from public memory like the dust of a bygone civilization.

Permanent Wave (Lantz/Universal, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, 9/29/29 – Walter Lantz/Bill Nolan/Tom Palmer, anim.). The storm in this one doesn’t even show up until the last minute and a half of the film. Oswald is first mate aboard what seems a literal “tub”, with cabin and smokestack mounted above deck. The vessel may not even have a working engine, as Oswald spends the film’s first minute towing the ship astride a large fish. In direct copy of “Steamboat Willie”, Oswald performs menial tasks under the foreboding shadow of Putrid Pete (who even at one point in the film duplicates Peg Leg Pete’s gag of grabbing Mickey’s midriff and stretching it, forcing Mickey to gather up his noodle torso and stuff it back into his pants). Oswald spots a mermaid on the shore of a small island, dancing a hula to the musical accompaniment of some of the local sea critters. Oswald joins the dance by climbing over to the island on the trail of music notes, providing an arc bridge from the ship. Pete spots the mermaid too, but has lecherous ideas, and kidnaps her, taking her aboard the ship. Oswald follows in the sea, and gets on board through another “arc” bridge which he provides himself. He spits water at the ship, then stretches his noodle torso to walk on the arc of water while his head stays in place spitting, finally dragging his head on board once his feet are on deck. Oswald really doesn’t get to prove himself much of a hero in this one, as Mother Nature takes up the battle for him from this point on.

Permanent Wave (Lantz/Universal, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, 9/29/29 – Walter Lantz/Bill Nolan/Tom Palmer, anim.). The storm in this one doesn’t even show up until the last minute and a half of the film. Oswald is first mate aboard what seems a literal “tub”, with cabin and smokestack mounted above deck. The vessel may not even have a working engine, as Oswald spends the film’s first minute towing the ship astride a large fish. In direct copy of “Steamboat Willie”, Oswald performs menial tasks under the foreboding shadow of Putrid Pete (who even at one point in the film duplicates Peg Leg Pete’s gag of grabbing Mickey’s midriff and stretching it, forcing Mickey to gather up his noodle torso and stuff it back into his pants). Oswald spots a mermaid on the shore of a small island, dancing a hula to the musical accompaniment of some of the local sea critters. Oswald joins the dance by climbing over to the island on the trail of music notes, providing an arc bridge from the ship. Pete spots the mermaid too, but has lecherous ideas, and kidnaps her, taking her aboard the ship. Oswald follows in the sea, and gets on board through another “arc” bridge which he provides himself. He spits water at the ship, then stretches his noodle torso to walk on the arc of water while his head stays in place spitting, finally dragging his head on board once his feet are on deck. Oswald really doesn’t get to prove himself much of a hero in this one, as Mother Nature takes up the battle for him from this point on.

Without transition shots or explanation, the sky suddenly turns from white to black. Lightning stabs down, the first bolt transforming into the shape of a drill and poking into the ship’s stern, the second forming a fist to deliver a downward blow amidships. The vessel reveals its “tub” base, exposing what amount to bathtub feet below the waterline, and further develops a face to react in shock. A third bolt acts like a saw, and temporarily splits the boat into two halves. Pulling itself together, the boat scrambles across the top of the choppy water, as if it were scaling mountains and descending into valleys. The water forms into a pair of hands, one grabbing the ship by the nose, and the other pulling down the “pants” of the ship’s stern and spanking its naked butt. (Bill Nolan, no doubt, takes free liberty on the drawings, arbitrarily moving the ship’s “face” from the bow to the cabin for reaction, since the nose of the vessel is hidden by the grip of the water.) The watery hands compress the ship like a accordion, then twist it like an old rag being wrung out, squeezing Oswald, Pete, and the mermaid from between the twists into the ocean. The ship is then batted out of the frame by one of the hands, never to be seen again. Oswald emerges, climbing atop a pier piling, and helps the mermaid up to the perch too, where they embrace. Pete rises from the waves, about to pounce, but the hands of the waves grab hold and pull him under, presumably to his doom. Oswald and the mermaid kiss, a black heart emerging from the smooch and growing to form a heart-shaped iris out. The final Universal Pictures logo depicts Oswald and the mermaid sitting on the lettering, still in embrace.

Without transition shots or explanation, the sky suddenly turns from white to black. Lightning stabs down, the first bolt transforming into the shape of a drill and poking into the ship’s stern, the second forming a fist to deliver a downward blow amidships. The vessel reveals its “tub” base, exposing what amount to bathtub feet below the waterline, and further develops a face to react in shock. A third bolt acts like a saw, and temporarily splits the boat into two halves. Pulling itself together, the boat scrambles across the top of the choppy water, as if it were scaling mountains and descending into valleys. The water forms into a pair of hands, one grabbing the ship by the nose, and the other pulling down the “pants” of the ship’s stern and spanking its naked butt. (Bill Nolan, no doubt, takes free liberty on the drawings, arbitrarily moving the ship’s “face” from the bow to the cabin for reaction, since the nose of the vessel is hidden by the grip of the water.) The watery hands compress the ship like a accordion, then twist it like an old rag being wrung out, squeezing Oswald, Pete, and the mermaid from between the twists into the ocean. The ship is then batted out of the frame by one of the hands, never to be seen again. Oswald emerges, climbing atop a pier piling, and helps the mermaid up to the perch too, where they embrace. Pete rises from the waves, about to pounce, but the hands of the waves grab hold and pull him under, presumably to his doom. Oswald and the mermaid kiss, a black heart emerging from the smooch and growing to form a heart-shaped iris out. The final Universal Pictures logo depicts Oswald and the mermaid sitting on the lettering, still in embrace.

Summertime (Van Buren/Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 10/13/29, John Foster/Harry Bailey, dir.) – Those of us who’ve experienced a few recent summers can feel for Farmer Al Falfa in this one. Most of the first half of the cartoon isn’t really much on subject, excepting a sequence where a perspiring mouse finds some relief by sitting in the shadow of a fat lady engaged in conversation at the beach, then passes the time by playing on a little horn, “In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree”. Farmer Al finally makes his appearance, poking his head out of his front door while the smiling sun beats down its waves upon the farm. Al is visibly sweating, and takes a peek at the thermometer outside his house. The thermometer mercury bobs up and down, rising, rising to the top of the glass tube. Then, it begins to spurt out the top of the thermometer as a trail of whistling steam. Finally, the whole thermometer explodes, as Farmer Al’s eyes widen and spin in disbelief. He starts to re-enter his house. Then, in a surreal shot that is absolutely startling, the sun decides to pay a personal visit, zooming into the camera foreground from vanishing point perspective, and staring Al in the face at his own front door! Al can’t rake the effect of the intense direct rays, and retreats to his living room. He collapses in a chair, tired and weary, but pauses to smell something inviting. On a nearby table are several bottles, likely of potions alcoholic. Also on the table is a glass of ice cubes which Al must have pulled out just before looking outside, considering they haven’t melted. Al’s eyelids lower to a happy, serene half-closed, as he begins mixing the contents of the bottles together in the glass, with the skill of a master chemist. Several close-ups show the expectant farmer in possibly the most contented mood of his entire career, his tongue smacking his lips in expectation, and his facial features registering the feeling of being in Seventh Heaven. The last bottle is nearly empty, and Al taps and squeezes the rigid glass bottle almost as if he were milking one of his cows, finally delivering exactly one drop into the glass. Perfection! Al holds his masterpiece of mixing high, ready to indulge. One of the ever-mischievous mice around the farmhouse emerges from the piano, and hops on the keys, playing a razzing stanza of “How Dry I Am.” Al notes this with a grumble, tossing a small object at the mouse and telling him to get out. Another mouse joins in from the opposite side of the room, playing a small tuba. Al waves it off, and the glass comes ever closer to his moistened lips. A third mouse appears, armed with a slingshot. He takes aim, and scores a direct hit, shattering Al’s glass, and spoiling all of its contents onto the floor. By now, our heart is breaking for the farmer, and even Al, for possibly the only time ever, sheds tears. But, his inborn streak of irascibility kicks in, and Al reaches for his shotgun, determined to take revenge upon his persecutors. Of course, his shot passes over the ducking mice, and hits the tail of the farmyard goat. In a standard perspective-angle run, the goat chases Al down the road, repeatedly butting him in the rear, for the cartoon’s close.

Summertime (Van Buren/Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 10/13/29, John Foster/Harry Bailey, dir.) – Those of us who’ve experienced a few recent summers can feel for Farmer Al Falfa in this one. Most of the first half of the cartoon isn’t really much on subject, excepting a sequence where a perspiring mouse finds some relief by sitting in the shadow of a fat lady engaged in conversation at the beach, then passes the time by playing on a little horn, “In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree”. Farmer Al finally makes his appearance, poking his head out of his front door while the smiling sun beats down its waves upon the farm. Al is visibly sweating, and takes a peek at the thermometer outside his house. The thermometer mercury bobs up and down, rising, rising to the top of the glass tube. Then, it begins to spurt out the top of the thermometer as a trail of whistling steam. Finally, the whole thermometer explodes, as Farmer Al’s eyes widen and spin in disbelief. He starts to re-enter his house. Then, in a surreal shot that is absolutely startling, the sun decides to pay a personal visit, zooming into the camera foreground from vanishing point perspective, and staring Al in the face at his own front door! Al can’t rake the effect of the intense direct rays, and retreats to his living room. He collapses in a chair, tired and weary, but pauses to smell something inviting. On a nearby table are several bottles, likely of potions alcoholic. Also on the table is a glass of ice cubes which Al must have pulled out just before looking outside, considering they haven’t melted. Al’s eyelids lower to a happy, serene half-closed, as he begins mixing the contents of the bottles together in the glass, with the skill of a master chemist. Several close-ups show the expectant farmer in possibly the most contented mood of his entire career, his tongue smacking his lips in expectation, and his facial features registering the feeling of being in Seventh Heaven. The last bottle is nearly empty, and Al taps and squeezes the rigid glass bottle almost as if he were milking one of his cows, finally delivering exactly one drop into the glass. Perfection! Al holds his masterpiece of mixing high, ready to indulge. One of the ever-mischievous mice around the farmhouse emerges from the piano, and hops on the keys, playing a razzing stanza of “How Dry I Am.” Al notes this with a grumble, tossing a small object at the mouse and telling him to get out. Another mouse joins in from the opposite side of the room, playing a small tuba. Al waves it off, and the glass comes ever closer to his moistened lips. A third mouse appears, armed with a slingshot. He takes aim, and scores a direct hit, shattering Al’s glass, and spoiling all of its contents onto the floor. By now, our heart is breaking for the farmer, and even Al, for possibly the only time ever, sheds tears. But, his inborn streak of irascibility kicks in, and Al reaches for his shotgun, determined to take revenge upon his persecutors. Of course, his shot passes over the ducking mice, and hits the tail of the farmyard goat. In a standard perspective-angle run, the goat chases Al down the road, repeatedly butting him in the rear, for the cartoon’s close.

The Haunted House (Disney, Mickey Mouse, 12/2/29 – Walt Disney, dir.) – A stormy night provides atmosphere for this Halloween-styled tale. Mickey trods down a country road in the dark of night, fighting against the force of a driving wind, which turns his umbrella iside out. With no protection from the elements, Mickey seeks shelter. An old house is visible to one side of the road, with lights in its windows. The windows, set in a row on the ground floor, with two additional windows spaced apart on the second floor, appear to form a jack-o-lantern style face, with the rising and falling window shades in the upper-story windows making the “eyes” appear to blink with every rush of wind. Mickey approaches the door of an enclosed porch attached to one side of the building, then knocks. As no one answers, Mickey tugs at the doorknob to see if it is unlocked. The building is so dilapidated, his tug and the force of the wind bring the porch crashing down, revealing a second door built directly into the side of the house, which slowly opens to beckon him inside. A howl like that of a wolf emerges from within, filling Mickey with fear. But the branches of a leafless tree outside extend in the wind to tickle Mickey in the rear end, surprising him, and causing him the jump inside the building. Most remaining action is interior, as Mickey is met by a self-locking door, bats, a giant spider, and the specter of Death accompanied by the cast of “The Skeleton Dance”. Mickey is forced to learn for the first time to play a pumper organ, to provide instrumental accompaniment for a skeletal jam session. He eventually escapes, only after finding more skeletons everywhere – in the doorknobs, in a Murphy bed (a pre-code married skeleton couple, sleeping together), in a rain barrel, and even in the outhouse, before fleeing over the hills.

The Haunted House (Disney, Mickey Mouse, 12/2/29 – Walt Disney, dir.) – A stormy night provides atmosphere for this Halloween-styled tale. Mickey trods down a country road in the dark of night, fighting against the force of a driving wind, which turns his umbrella iside out. With no protection from the elements, Mickey seeks shelter. An old house is visible to one side of the road, with lights in its windows. The windows, set in a row on the ground floor, with two additional windows spaced apart on the second floor, appear to form a jack-o-lantern style face, with the rising and falling window shades in the upper-story windows making the “eyes” appear to blink with every rush of wind. Mickey approaches the door of an enclosed porch attached to one side of the building, then knocks. As no one answers, Mickey tugs at the doorknob to see if it is unlocked. The building is so dilapidated, his tug and the force of the wind bring the porch crashing down, revealing a second door built directly into the side of the house, which slowly opens to beckon him inside. A howl like that of a wolf emerges from within, filling Mickey with fear. But the branches of a leafless tree outside extend in the wind to tickle Mickey in the rear end, surprising him, and causing him the jump inside the building. Most remaining action is interior, as Mickey is met by a self-locking door, bats, a giant spider, and the specter of Death accompanied by the cast of “The Skeleton Dance”. Mickey is forced to learn for the first time to play a pumper organ, to provide instrumental accompaniment for a skeletal jam session. He eventually escapes, only after finding more skeletons everywhere – in the doorknobs, in a Murphy bed (a pre-code married skeleton couple, sleeping together), in a rain barrel, and even in the outhouse, before fleeing over the hills.

The Haunted Ship (Van Buren/Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 4/27/30 – John Foster/Mannie Davis, dir.) – Waffles and Don (the early cat and dog prototypes for Van Buren’s Tom and Jerry) are intrepid aviators, who seem to be bound for nowhere in particular. Their aircraft is of the pot-bellied variety with only a single seat – so little Don is left to sit on the elevator surfaces of the tail (a pretty precarious place to sit if you’re truing to maintain elevation), and occasionally take exercise by practicing his dancing steps, while Waffles plays a tune on the engine’s many exhaust pipes like a xylophone. A black cloud overhead begins to threaten, by forming into a face, and taking an undignified spit at them. Another bulges at the top to form the silhouettes of a three-man team, two manning a water pump, and the third taking filled buckets of water pumped from the cloud and tossing them overboard at our heroes’ plane. The boys are adaptable to such weather changes, and pull out pairs of oars to row their craft through the sky. Suddenly, lightning strikes Don, who reacts with a yowl. Another bolt forms into the figure of a man, and takes a seat on the wing, forcing Don to eject him with a swift kick. The lightning is angered, and pursues them in a cloud-hopping race through the sky. All three dive inside a black cloud and fight it out, with the plane the loser. As the plane falls toward the ocean, the boys, for no reason, lower a ladder from its belly hatch, and dive into the water a few seconds before the plane – then use the ladder to climb back into the plane again just in time to accompany it as it sinks below the waves. They are serenaded by a walrus, singing “Many brave hearts lie asleep in the deep.” The rest of the film follows our heroes through an undersea adventure in the sunken ship of Davy Jones, developing into a musicale that awakens the skeleton of Davy himself for an end-of-reel pursuit that never really resolves itself with any coherent ending.

The Haunted Ship (Van Buren/Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 4/27/30 – John Foster/Mannie Davis, dir.) – Waffles and Don (the early cat and dog prototypes for Van Buren’s Tom and Jerry) are intrepid aviators, who seem to be bound for nowhere in particular. Their aircraft is of the pot-bellied variety with only a single seat – so little Don is left to sit on the elevator surfaces of the tail (a pretty precarious place to sit if you’re truing to maintain elevation), and occasionally take exercise by practicing his dancing steps, while Waffles plays a tune on the engine’s many exhaust pipes like a xylophone. A black cloud overhead begins to threaten, by forming into a face, and taking an undignified spit at them. Another bulges at the top to form the silhouettes of a three-man team, two manning a water pump, and the third taking filled buckets of water pumped from the cloud and tossing them overboard at our heroes’ plane. The boys are adaptable to such weather changes, and pull out pairs of oars to row their craft through the sky. Suddenly, lightning strikes Don, who reacts with a yowl. Another bolt forms into the figure of a man, and takes a seat on the wing, forcing Don to eject him with a swift kick. The lightning is angered, and pursues them in a cloud-hopping race through the sky. All three dive inside a black cloud and fight it out, with the plane the loser. As the plane falls toward the ocean, the boys, for no reason, lower a ladder from its belly hatch, and dive into the water a few seconds before the plane – then use the ladder to climb back into the plane again just in time to accompany it as it sinks below the waves. They are serenaded by a walrus, singing “Many brave hearts lie asleep in the deep.” The rest of the film follows our heroes through an undersea adventure in the sunken ship of Davy Jones, developing into a musicale that awakens the skeleton of Davy himself for an end-of-reel pursuit that never really resolves itself with any coherent ending.

Noah Knew His Ark (Van Buren/Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 5/25/30 – John Foster/Mannie Davis, dir.) – The boys who stayed at Van Buren after Paul Terry’s departure are finally forced to abandon Farmer Al Falfa, whom Terry continued to claim rights to at his newly-formed Terrytoons studio. However, this doesn’t stop them from lifting gags from Terry’s old productions. The opening gag is recycled directly from the start of Terry’s film currently known as “The Big Flood” (though I believe this to be a re-titling of 1923’s “Troubles on the Ark”), with Noah experiencing pain in his foot from the throbbing of “corns” (depicted as ears of the vegetable growing from his toes, then pulsating like pistons from his bony feet). Noah knows rain is imminent. A jagged bolt of lightning develops its back-and-forth zig zag pattern set to the notes of “Shave and a haircut, two bits.” A black cloud shapes itself like a human, picks up a smaller round cloud like a bowling ball, and rolls for a thundering strike. Lightning blasts Noah out of his trousers. He dives inside his outhouse-style home, while his trousers knock on the door with their suspender buckles to gain entry. Another lightning strike demolishes the outhouse, and Noah runs for better shelter, carrying the roof from the structure atop a pole like a small umbrella. The animals (again including some dinosaurs) and Noah run for the already-waiting ark, and shove off – again with, what else, a separate small boat in tow for the skunks. (John Foster simply couldn’t get away from this gag, having just used it again in the preceding year in Van Buren’s “The Big Scare”.) Inconsistently, all rain disappears from the skies without so much as a dissolve, allowing Noah to musically entertain his passengers in a dance (a convenient shortcut, avoiding the supplying of special effects throughout the remaining film). The ark itself develops a face, arms and legs, and dances a toe dance atop the waves. As Noah changes the musical program to a sing along version of “It Ain’t Gonna Rain No Mo’” ( a current national ear-ache hit which had become a staple for singer Wendell Hall), the skunks climb aboard the tow rope, and engage in the usual chase of the captain and passengers. Several of the last shots are nearly traced verbatim from “The Big Flood”, proving that Paul Terry himself wasn’t needed to bring about the habit of raiding the drawing morgue for recyclable material.

Noah Knew His Ark (Van Buren/Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 5/25/30 – John Foster/Mannie Davis, dir.) – The boys who stayed at Van Buren after Paul Terry’s departure are finally forced to abandon Farmer Al Falfa, whom Terry continued to claim rights to at his newly-formed Terrytoons studio. However, this doesn’t stop them from lifting gags from Terry’s old productions. The opening gag is recycled directly from the start of Terry’s film currently known as “The Big Flood” (though I believe this to be a re-titling of 1923’s “Troubles on the Ark”), with Noah experiencing pain in his foot from the throbbing of “corns” (depicted as ears of the vegetable growing from his toes, then pulsating like pistons from his bony feet). Noah knows rain is imminent. A jagged bolt of lightning develops its back-and-forth zig zag pattern set to the notes of “Shave and a haircut, two bits.” A black cloud shapes itself like a human, picks up a smaller round cloud like a bowling ball, and rolls for a thundering strike. Lightning blasts Noah out of his trousers. He dives inside his outhouse-style home, while his trousers knock on the door with their suspender buckles to gain entry. Another lightning strike demolishes the outhouse, and Noah runs for better shelter, carrying the roof from the structure atop a pole like a small umbrella. The animals (again including some dinosaurs) and Noah run for the already-waiting ark, and shove off – again with, what else, a separate small boat in tow for the skunks. (John Foster simply couldn’t get away from this gag, having just used it again in the preceding year in Van Buren’s “The Big Scare”.) Inconsistently, all rain disappears from the skies without so much as a dissolve, allowing Noah to musically entertain his passengers in a dance (a convenient shortcut, avoiding the supplying of special effects throughout the remaining film). The ark itself develops a face, arms and legs, and dances a toe dance atop the waves. As Noah changes the musical program to a sing along version of “It Ain’t Gonna Rain No Mo’” ( a current national ear-ache hit which had become a staple for singer Wendell Hall), the skunks climb aboard the tow rope, and engage in the usual chase of the captain and passengers. Several of the last shots are nearly traced verbatim from “The Big Flood”, proving that Paul Terry himself wasn’t needed to bring about the habit of raiding the drawing morgue for recyclable material.

The Picnic (Disney/Columbia, Mickey Mouse, 10/23/30, Burt Gillett, dir.) – An historic film for being the first instance where Pluto appears as pet of the mice – with two differences from usual. He is Minnie’s pet, not Mickey’s, and she has named him “Little Rover”, despite the fact he is twice the size of either of them. Pluto’s animation is primitive and rudimentary as compared to the character we all know and love, but still exhibits more personality than the average cartoon canine of the day. The day’s outing is fairly typical of Disney’s early sound cartoons – mostly an excuse for an extended dance to “In the Good Old Summertime”. It includes some brief thievery by various species from Mickey’s picnic spread, including some early larcenous ants which I overlooked in my previous columns on such species on this website. The climax of the film has dark storm clouds build in the sky, while a bolt of lightning forms into the shape of a corkscrew, driving itself into the end of a cloud as if it were a wine bottle, then tugging to pop the cloud’s “cork”. The cloud then tips to pour out its watery contents on the earth below, with a primitive vocal sound effect of “Blub blub blub”, that sounds like it is voiced by Disney himself. Mickey scampers to gather up what is left of the picnic from the unexpected downpour, encountering more animals than remaining food. He and Minnie retreat to their car, which is a roofless convertible, leaving them considerably exposed to the elements (except for a small umbrella held by Minnie. Pluto was too big to ride inside, and had earlier made the trip to the picnic grounds in tow behind the car from his leash. Mickey is having trouble seeing through the rain pelting the car’s windshield, and whistles for Pluto, having the pip take a seat on a special perch atop the windshield frame. This allows Pluto’s tail to dangle below the frame line, its wagging providing a need piece of safety equipment the car was lacking – a windshield wiper.

The Picnic (Disney/Columbia, Mickey Mouse, 10/23/30, Burt Gillett, dir.) – An historic film for being the first instance where Pluto appears as pet of the mice – with two differences from usual. He is Minnie’s pet, not Mickey’s, and she has named him “Little Rover”, despite the fact he is twice the size of either of them. Pluto’s animation is primitive and rudimentary as compared to the character we all know and love, but still exhibits more personality than the average cartoon canine of the day. The day’s outing is fairly typical of Disney’s early sound cartoons – mostly an excuse for an extended dance to “In the Good Old Summertime”. It includes some brief thievery by various species from Mickey’s picnic spread, including some early larcenous ants which I overlooked in my previous columns on such species on this website. The climax of the film has dark storm clouds build in the sky, while a bolt of lightning forms into the shape of a corkscrew, driving itself into the end of a cloud as if it were a wine bottle, then tugging to pop the cloud’s “cork”. The cloud then tips to pour out its watery contents on the earth below, with a primitive vocal sound effect of “Blub blub blub”, that sounds like it is voiced by Disney himself. Mickey scampers to gather up what is left of the picnic from the unexpected downpour, encountering more animals than remaining food. He and Minnie retreat to their car, which is a roofless convertible, leaving them considerably exposed to the elements (except for a small umbrella held by Minnie. Pluto was too big to ride inside, and had earlier made the trip to the picnic grounds in tow behind the car from his leash. Mickey is having trouble seeing through the rain pelting the car’s windshield, and whistles for Pluto, having the pip take a seat on a special perch atop the windshield frame. This allows Pluto’s tail to dangle below the frame line, its wagging providing a need piece of safety equipment the car was lacking – a windshield wiper.

• Read more about THE PICNIC in this post from February 2022 by J.B. Kaufman.

Winter (Disney/Columbia, Silly Symphony, 10/30/30 – Burt Gillett, dir.), may mark one of the earliest (at least for sound) appearances of the groundhog for a weather forecast. The film is for the most part the typical musicale of various species cavorting in the snow, though it does open with a nice atmospheric shot of a wolf in the night, trudging through the snow against the driving force of a blizzard wind, and howling at the moon. Much of the action is set to the light-classical favorite “The Skater’s Waltz”, which Disney would return to years later for an all-star Mickey Mouse early color reel, On Ice (1935). The final sequence has the animals gathering around the door of “Mr. Groundhog, Weather Prophet”. A skunk is sent forth to cautiously knock on the door. (For gosh sakes! If you want the groundhog to come out, shouldn’t you send any other kind of animal to do the knocking?) The door slowly creaks open, and Mr. Groundhog emerges, covering his eyes with one hand. He lowers his hand, opens his eyes, and looks in all directions around him. No shadow. He smiles to the crowd, who knows what that means – a cause for celebration, that Spring is just around the corner. All begin to dance about, not noticing that above them, there is a break developing in the clouds, and the sun is beginning to peep through. A shadow materializes from the groundhog’s feet, which he eventually notices, reacting in fright. He races back into his home, and shuts the door. The shadow takes on a life of its own, and is trapped outside when the door closes. It tugs at the locked door, and pounds on it in attempt to gain entrance, while the rest of the animals stare at this unexpected development. Suddenly, the clouds form again, dissolving the shadow from the scene, and blasts of driving snow again begin to cover the landscape. Six more weeks of winter. The animals all scatter back to their respective homes, or whatever shelter they can find. The last shot depicts a hollow tree rapidly filling up with squirrels and other small animals, then having its entrance plugged by the form of an oversize grizzly bear. A porcupine is left outside and denied entrance. He solves this problem by shooting a few quills off his back into the bear’s rear. The bear reacts in pain, forcing himself through the small opening, and ejecting several squirrels out limbs of the hollow tree in the process. Now, there is plenty of room for Mr. Porcupine, who struts into the tree proudly, without resistance.

Winter (Disney/Columbia, Silly Symphony, 10/30/30 – Burt Gillett, dir.), may mark one of the earliest (at least for sound) appearances of the groundhog for a weather forecast. The film is for the most part the typical musicale of various species cavorting in the snow, though it does open with a nice atmospheric shot of a wolf in the night, trudging through the snow against the driving force of a blizzard wind, and howling at the moon. Much of the action is set to the light-classical favorite “The Skater’s Waltz”, which Disney would return to years later for an all-star Mickey Mouse early color reel, On Ice (1935). The final sequence has the animals gathering around the door of “Mr. Groundhog, Weather Prophet”. A skunk is sent forth to cautiously knock on the door. (For gosh sakes! If you want the groundhog to come out, shouldn’t you send any other kind of animal to do the knocking?) The door slowly creaks open, and Mr. Groundhog emerges, covering his eyes with one hand. He lowers his hand, opens his eyes, and looks in all directions around him. No shadow. He smiles to the crowd, who knows what that means – a cause for celebration, that Spring is just around the corner. All begin to dance about, not noticing that above them, there is a break developing in the clouds, and the sun is beginning to peep through. A shadow materializes from the groundhog’s feet, which he eventually notices, reacting in fright. He races back into his home, and shuts the door. The shadow takes on a life of its own, and is trapped outside when the door closes. It tugs at the locked door, and pounds on it in attempt to gain entrance, while the rest of the animals stare at this unexpected development. Suddenly, the clouds form again, dissolving the shadow from the scene, and blasts of driving snow again begin to cover the landscape. Six more weeks of winter. The animals all scatter back to their respective homes, or whatever shelter they can find. The last shot depicts a hollow tree rapidly filling up with squirrels and other small animals, then having its entrance plugged by the form of an oversize grizzly bear. A porcupine is left outside and denied entrance. He solves this problem by shooting a few quills off his back into the bear’s rear. The bear reacts in pain, forcing himself through the small opening, and ejecting several squirrels out limbs of the hollow tree in the process. Now, there is plenty of room for Mr. Porcupine, who struts into the tree proudly, without resistance.

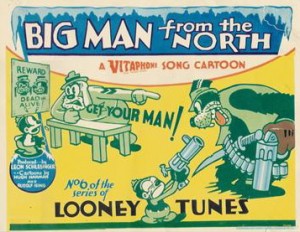

Big Man From the North (Harman-Ising/Warner, Looney Tunes (Bosko), January, 1931 (precise date unknown) – Bosko joins the Mounted Police (though he prefers dog sled to a horse for transportation). The cartoon’s credits are momentarily interfered with by a blast of snow from an icy wind (missing an opportunity by not having the lettering blown off the screen). The sign outside the station house and the trees nearby are nearly bent to the breaking point by the sideways gale force winds. Inside, behind a door held closed with a large wooden beam placed across it, a police sergeant paces the floor impatiently, awaiting the arrival of our hero to assume his post of duty. Somehow sensing Bosko’s approach outside in spite of the overriding sound of the whistling wind, the Sergeant unbolts the door. Bosko doesn’t merely enter – he is blown inside, and performs a sort of “Moonwalk” step just to stay in place and keep from being blown across the room. The Sergeant attempts to shut the door, but can muster no more force against the rushing sleet pouring in the doorway than to get the door halfway shut. Bosko seizes the pantleg of the Sergeant’s trousers to hold his position, but is blown off his feet, still clinging to the trousers. The pants slip down to the Sergeant’s ankles, then under his feet entirely, tossing Bosko and the pants against the opposite wall. Bosko struggles back to help the Sergeant, this time grabbing onto the Sergeant’s long underwear. The drop-seat rips off, exposing a butt-crack of the Sergeant, as Bosko is tossed back against the wall again. The Sergeant finally gets the door closed and bolted, but the wind demonstrates its force by briefly bending the door at both top and bottom, with the only portion of the door holding firm being the middle where the wooden beam lies across it. With some embarrassment, Bosko holds up the Sergeant’s pants to him, and asks. “These yours, Mister Sergeant?” The Sergeant re-dresses himself into regulation uniform, then shows Bosko a wanted poster of an unnamed tough hombre, and gives Bosko the same order received by Oswald Rabbit in the Disney days of “Ozzie of the Mounted” – “Get your man!” “Who, me?” timidly asks Bosko. “Go”, orders the Sergeant.

Big Man From the North (Harman-Ising/Warner, Looney Tunes (Bosko), January, 1931 (precise date unknown) – Bosko joins the Mounted Police (though he prefers dog sled to a horse for transportation). The cartoon’s credits are momentarily interfered with by a blast of snow from an icy wind (missing an opportunity by not having the lettering blown off the screen). The sign outside the station house and the trees nearby are nearly bent to the breaking point by the sideways gale force winds. Inside, behind a door held closed with a large wooden beam placed across it, a police sergeant paces the floor impatiently, awaiting the arrival of our hero to assume his post of duty. Somehow sensing Bosko’s approach outside in spite of the overriding sound of the whistling wind, the Sergeant unbolts the door. Bosko doesn’t merely enter – he is blown inside, and performs a sort of “Moonwalk” step just to stay in place and keep from being blown across the room. The Sergeant attempts to shut the door, but can muster no more force against the rushing sleet pouring in the doorway than to get the door halfway shut. Bosko seizes the pantleg of the Sergeant’s trousers to hold his position, but is blown off his feet, still clinging to the trousers. The pants slip down to the Sergeant’s ankles, then under his feet entirely, tossing Bosko and the pants against the opposite wall. Bosko struggles back to help the Sergeant, this time grabbing onto the Sergeant’s long underwear. The drop-seat rips off, exposing a butt-crack of the Sergeant, as Bosko is tossed back against the wall again. The Sergeant finally gets the door closed and bolted, but the wind demonstrates its force by briefly bending the door at both top and bottom, with the only portion of the door holding firm being the middle where the wooden beam lies across it. With some embarrassment, Bosko holds up the Sergeant’s pants to him, and asks. “These yours, Mister Sergeant?” The Sergeant re-dresses himself into regulation uniform, then shows Bosko a wanted poster of an unnamed tough hombre, and gives Bosko the same order received by Oswald Rabbit in the Disney days of “Ozzie of the Mounted” – “Get your man!” “Who, me?” timidly asks Bosko. “Go”, orders the Sergeant.

Bosko unbars the door again, and struggles against the winds to get outside. There awaits a team of mismatched sled dogs (te center one so small, his feet don’t even reach the ground when in harness). The dogs too are feeling the effects of the ill wind, being simultaneously blown into the air, only kept from separating from the sled by the harness straps. As they receive the order from Bosko to “Mush”, they are blown again by the wind, stretching backwards and vertically so that they nearly transform into tall thin ribbons. The team slides down an icy slope, colliding with the side of a log cabin saloon. The impact melds the three dogs into one another, like they were clay creations on the “Gumby” show, and they march away as a long continuous dachshund-style body with heads protruding on both ends and in the middle. Continuity here goes out the window, as the storm effects are abruptly discontinued by the next shot. Then, the action moves primarily indoors, giving Bosko opportunity to fill time in a musical number with Honey before a final showdown with the wanted villain. Bosko defies all Mountie protocol, by confronting the bad guy with a pistol that is really a popgun. In the end, Bosko learns to upgrade weapons, appearing out of a spittoon armed with a machine gun, stabbing the villain deeply in the rear with a long sword, and blasting him point blank with a hunting blunderbuss from the wall, revealing the hulking villain is really a skinny shrimp once his fur is blasted away. Bosko again breaks Mountie riles by letting the helpless villain escape over the hills rather than bringing him in, yet is cheered by the saloon folk as a hero anyway. Even Dudley Do-Right would have known better.

Bosko unbars the door again, and struggles against the winds to get outside. There awaits a team of mismatched sled dogs (te center one so small, his feet don’t even reach the ground when in harness). The dogs too are feeling the effects of the ill wind, being simultaneously blown into the air, only kept from separating from the sled by the harness straps. As they receive the order from Bosko to “Mush”, they are blown again by the wind, stretching backwards and vertically so that they nearly transform into tall thin ribbons. The team slides down an icy slope, colliding with the side of a log cabin saloon. The impact melds the three dogs into one another, like they were clay creations on the “Gumby” show, and they march away as a long continuous dachshund-style body with heads protruding on both ends and in the middle. Continuity here goes out the window, as the storm effects are abruptly discontinued by the next shot. Then, the action moves primarily indoors, giving Bosko opportunity to fill time in a musical number with Honey before a final showdown with the wanted villain. Bosko defies all Mountie protocol, by confronting the bad guy with a pistol that is really a popgun. In the end, Bosko learns to upgrade weapons, appearing out of a spittoon armed with a machine gun, stabbing the villain deeply in the rear with a long sword, and blasting him point blank with a hunting blunderbuss from the wall, revealing the hulking villain is really a skinny shrimp once his fur is blasted away. Bosko again breaks Mountie riles by letting the helpless villain escape over the hills rather than bringing him in, yet is cheered by the saloon folk as a hero anyway. Even Dudley Do-Right would have known better.

Next Time: More blowhards from the early-day talkies.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

“Permanent Wave” is a disgusting cartoon, with all that spitting and regurgitating, not to mention the opaquing errors and the fact that they couldn’t even synchronise Oswald’s hand-clapping to the musical beat. This is really primitive stuff.

Ub Iwerks would shortly rework the essential elements of “The Haunted House” into the Flip the Frog short “Spooks”, from the opening where the hero seeks shelter from stormy weather to the skeleton hootenanny. Flip, like Mickey, even answers “Yes, ma’am!” to a deep-voiced skeleton.

Speaking of reused gags, the one with the corkscrew-shaped lightning bolt making a hole in a cloud and unleashing a downpour in “The Picnic” had been previously used in the Silly Symphony “Springtime” (24/10/29 — Ub Iwerks, dir.), proving that you can’t have “springtime” without an April shower. A tree down below welcomes the rainfall and proceeds to shower itself in it, cheerfully scrubbing its limbs, armpits, and the knotholes that serve as its ears and navel. But then a bolt of lightning strikes the tree’s posterior, and a segment of bark drops down like the butt flap of an old-fashioned union suit. The tree runs off in embarrassment. Then the rain stops, and all the insects resume their cavorting to the strains of Ponchielli.

And at the end of the Silly Symphony “Autumn” (13/2/30 — Iwerks), autumn comes to an end with the first snowfall. The animals seek shelter in hollow trees, logs, and even a scarecrow’s union suit, whose butt flap predictably falls open for the iris out. If the cartoons of the ’30s are any indication of public tastes, people must have thought butt flaps were the funniest thing in the world back then.

When I was a kid, I wondered why Dennis the Menace always had the butt flap on his pajamas hanging open. How negligent was Alice that she couldn’t sew on a frikkin’ button?

Of course, today it’s fart jokes and kicks in the crotch that are considered the height of wit.

Wow, a spittoon, outhouse, AND a chamber pot in The Haunted House ? Too bad the Academy wasn’t awarding animated shorts at this time–This is your winner right here.

Big Man from the North is just plain boring, which is odd for a cartoon from the early 1930s. This is a problem for most Harman-Ising output of the 1930s: they churned out derivative and bland imitations of much better cartoons despite having higher budgets than most of the competition.

I saw “Noah Knew His Ark” under a very odd circumstance – during a 7th-grade science class – perhaps the teacher didn’t have a lesson planned that morning (we often did cool stuff like making batteries using lead strips). He projected a vintage 16mm print with original titles (including the crowing Pathe rooster). – and we thought that the “corns” gag was, well, corny.

In “Big Man from the North,” the villain’s peg leg keeps switching back and forth between the left and the right side, much like Igor’s (pronounced “eye-gore”) hump in “Blazing Saddles.” And at the end, he doesn’t have a peg leg at all.