Here’s some operatic Greek mythology for today’s breakdown!

The outline for The Goddess of Spring, circulated around the studio on April 6, 1934, suggested a Silly Symphony that would burlesque grand opera. Bill Cottrell and his story team used source material originating from the myth of Persephone, the Greek goddess of eternal spring, abducted by the lord of the underworld Pluto, to proclaim her as a permanent bride. Goddess is depicted as a miniature opera, with music and lyrics by Leigh Harline and Larry Morey, with vocals sung by narrator Kenny Baker—the featured singer of Jack Benny’s popular radio program shortly after this film’s release—and operatic performer Tudor Williams as Pluto; the vocalist for Persephone is unconfirmed. This film posed a challenge for the studio, in animating two human characters in a delicate fashion, but the results reveal a problematic struggle.

The outline for The Goddess of Spring, circulated around the studio on April 6, 1934, suggested a Silly Symphony that would burlesque grand opera. Bill Cottrell and his story team used source material originating from the myth of Persephone, the Greek goddess of eternal spring, abducted by the lord of the underworld Pluto, to proclaim her as a permanent bride. Goddess is depicted as a miniature opera, with music and lyrics by Leigh Harline and Larry Morey, with vocals sung by narrator Kenny Baker—the featured singer of Jack Benny’s popular radio program shortly after this film’s release—and operatic performer Tudor Williams as Pluto; the vocalist for Persephone is unconfirmed. This film posed a challenge for the studio, in animating two human characters in a delicate fashion, but the results reveal a problematic struggle.

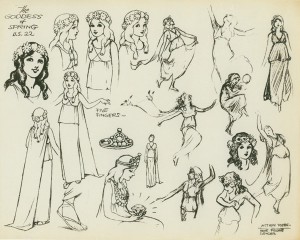

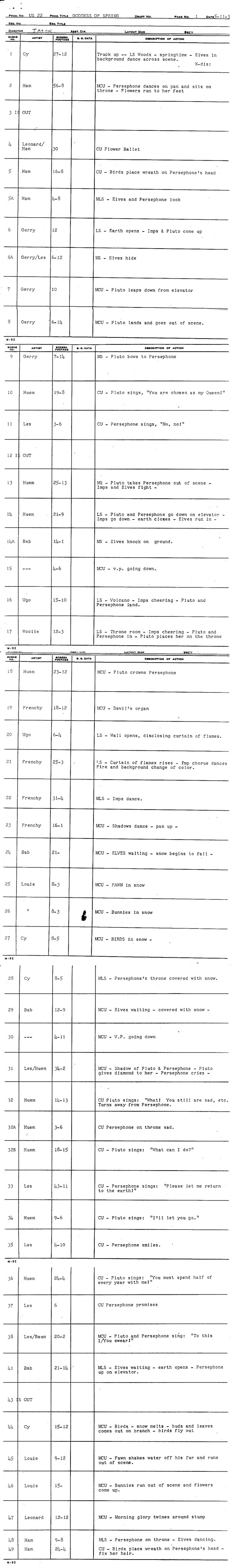

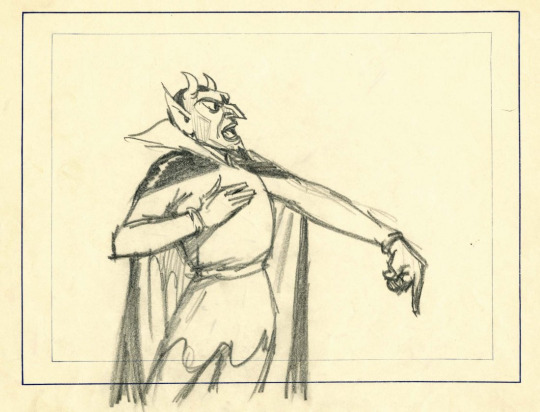

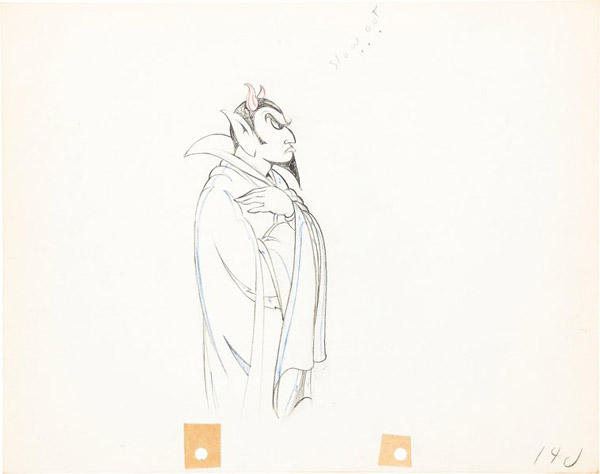

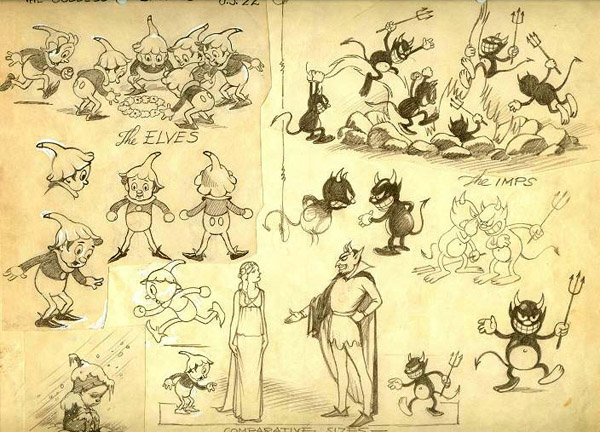

Persephone’s key animators used available references from the staffers for this daunting assignment. The opening dance in Goddess, animated by Ham Luske, appears more elastic than elegant, as her arms swoop down, inadvertently resembling rubber hose animation. He used his assistant, Eric Larson, to act out her scenes; Dick Huemer recalled Luske using his wife for Persephone, as well. Les Clark, using his sister Marceil—an ink and paint artist for the studio—as a model for the animation, handles the scenes of Persephone in Hades. Dick Huemer primarily animates the scenes with Pluto, but Gerry Geronimi does his first scenes, as he erupts into the earth; Geronimi’s drawing of Pluto gives him a characteristic grin, without many of Huemer’s details on the face—specifically, lips. Other artists credited on the draft, animate on non-principal characters, such as Art Babbitt handling the forlorn elves waiting for Persephone as winter arrives.

During this period of the Silly Symphonies, Wilfred Jackson tended to have different animators animate two characters on-screen within the same scene. In the draft for this film, it credits Gerry Geronimi for scene 9, animating both Pluto and Persephone; likewise for scenes 13 and 14, Dick Huemer is credited for both characters. Since Les Clark is credited with animation on Persephone during this portion of the film, it’s interesting to see Geronimi and Huemer credited for her scenes. However, no information from the exposure sheets or sweatbox notes is available at the moment to confirm this to be entirely accurate.

During this period of the Silly Symphonies, Wilfred Jackson tended to have different animators animate two characters on-screen within the same scene. In the draft for this film, it credits Gerry Geronimi for scene 9, animating both Pluto and Persephone; likewise for scenes 13 and 14, Dick Huemer is credited for both characters. Since Les Clark is credited with animation on Persephone during this portion of the film, it’s interesting to see Geronimi and Huemer credited for her scenes. However, no information from the exposure sheets or sweatbox notes is available at the moment to confirm this to be entirely accurate.

By 1934, besides the casting of animators, the Silly Symphonies were highly advanced in their effects animation, handled by specialized artists Cy Young and Ugo D’Orsi. Goddess’ effects animation is striking—in Hades, Pluto’s demonic imps dance around a swelling flame (animated by Frenchy de Tremaudan), which alternates luminous color and emits fireworks, like a geyser. Moreover, their shadows are casted against the wall. The contrast between high opera is compromised as they sing “Hi De Hades”, a hot jazz tune imitative of popular bandleader Cab Calloway. The budget for this film, as a result, rose higher than previous Disney cartoons around 1934, which averaged around $25,000. The cost for this film ran up to $37,605.02.

In hindsight to the film’s failures, Wilfred Jackson noted in a lecture to a studio audience five years after its release that the film didn’t make its broad pastiche on grand opera clear to the audience. Human characters for the studio needed more examination, particularly in emotion; for instance, Persephone’s expressions in this film display a lack of range in this film, set against Pluto’s melodramatic mannerisms; however, both characters have appendages that lack joints and angular lines. By August 1934, while Goddess was still in production, a feature-length animated film based on Snow White took form in its earliest stages, as submissions for characters, situations and songs were suggested. By October, a month before Goddess was released, an 18-page outline was completed and distributed around the studio.

In hindsight to the film’s failures, Wilfred Jackson noted in a lecture to a studio audience five years after its release that the film didn’t make its broad pastiche on grand opera clear to the audience. Human characters for the studio needed more examination, particularly in emotion; for instance, Persephone’s expressions in this film display a lack of range in this film, set against Pluto’s melodramatic mannerisms; however, both characters have appendages that lack joints and angular lines. By August 1934, while Goddess was still in production, a feature-length animated film based on Snow White took form in its earliest stages, as submissions for characters, situations and songs were suggested. By October, a month before Goddess was released, an 18-page outline was completed and distributed around the studio.

Les Clark claimed Goddess wasn’t an initial springboard for the studio to begin production on Snow White. The outline, as Disney and his staff envisioned the film during story meetings, presented a comedic approach in order to enthrall audiences, without many of the serious elements, which developed later. For instance, a haughty, heavy-set queen, in a “cartoony” light meant to serve as a danger to Snow White, instead of portrayed as conniving as her character matured. Clark admitted to his difficulty in animating Persephone to Disney, and apologized. Disney said to Clark, “I guess we could do better next time,” after which the studio expanded, and pursued a longer format for an animated fairy tale—a feat unprecedented in American animation.

Enjoy!

(Thanks to Mark Kausler, Michael Barrier and J.B. Kaufman for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Legend has is that using human models for Goddess of Spring inspired Walt Disney and his animation crew to use human models for Snow White,Prince Charming, The Evil Queen, The Old Hag and the Seven Dwarfs for their first full length animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs which was released a few years later.

Something I’ve neglected to mention—for a film that strived for progression in its realistic animation for the lead characters, some designs are questionable; Pluto’s imps in Hades, more or less, resemble the minions in another Silly Symphony set in the underworld, HELL’S BELLS (1929).

They did a terrific job with Snow White, but you can see they still had certain problems (the prince originally had more scenes but he only appears at the end with scarce dialogue. The comic strip adaption at the time made up for this). Starting with Pinocchio, they went right back to the somewhat cartoony designs of their Silly Symphonies (The Blue Fairy looks almost out of place).

Like, for instance the Queen captured the Prince and put him in chains down the dudgeon

All I could think of was Pearl Pureheart and Oil Can Harry. I was waiting for Mighty Mouse to save the day.

Thanks for the post, Devon. I had not realized that the original idea behind Goddess of Spring was a humorous one, not a serious one. The cartoon comes off as a very serious story, with comic overtones in the “Hi-De-Hades” number, obviously inspired by Cab Calloway. I’m sure that Walt wanted Dick Huemer to animate Pluto because Dick understood opera so well. I love the music in this cartoon especially, and Kenny Baker’s vocal on the sung narration. The Goddess of Spring was partially successful at conveying a melancholy tone, which Walt accomplished in Snow White, Bambi and Dumbo.

I always loved the “Hi De Hades” scene. I believe there’s a shout-out on Sleeping Beauty, with Maleficent’s goons dancing around the fire. Also, I think the demons have a cameo on Who Framed Roger Rabbit during the Maroon Studios scene, walking by Eddie after the hippo on the bench gag.

Scene 38 is credited on the draft to “Les/Baum”, which has been interpreted on the video as “Les Clark / Dick Huemer” (with “Baum” being a typo for “Huem”?) In their book, Merritt and Kaufman speculate that “Baum” is Jim Baumeister (the original a.d. for “Sorcerer’s Apprentice”.)

Are the lyrics from the Hi De Hades song available anywhere?