Happy to be back, folks! Here’s an animator breakdown of a Mickey Mouse short I have wanted to write about for a long time…

Happy to be back, folks! Here’s an animator breakdown of a Mickey Mouse short I have wanted to write about for a long time…

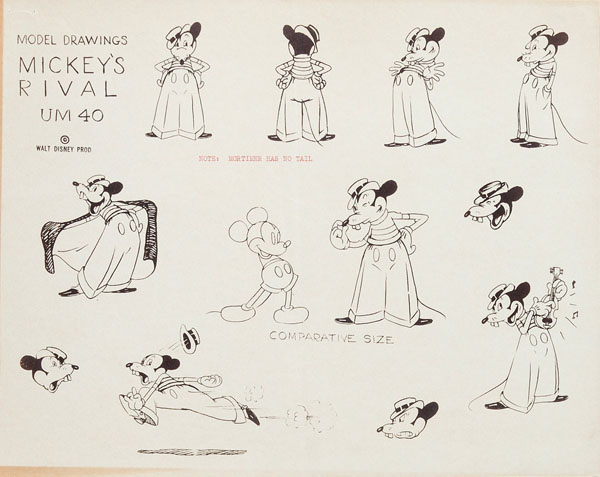

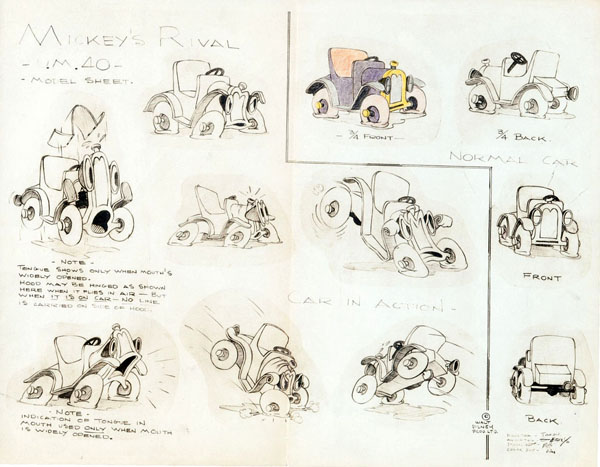

Production records for many of the 1930s Disney short films are scattered, even for a project that underwent intermittent changes. Mickey’s Rival was in the production pipeline in late 1935 but was delayed for unknown reasons. Surviving model sheets indicate its original production number as UM 40 but was shifted to UM 42, and other Mickey Mouse cartoons pushed ahead of it.

Production records for many of the 1930s Disney short films are scattered, even for a project that underwent intermittent changes. Mickey’s Rival was in the production pipeline in late 1935 but was delayed for unknown reasons. Surviving model sheets indicate its original production number as UM 40 but was shifted to UM 42, and other Mickey Mouse cartoons pushed ahead of it.

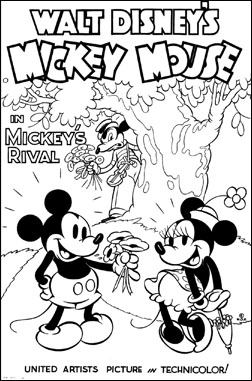

The rival’s name in the film, Mortimer Mouse, plays as an autobiographical in-joke; in 1928, as repeated stories from Walt Disney dictate, Mortimer was his first choice as the name of his new mouse character. His wife Lillian disliked such a name, as she described it as “too depressing.” About eight years later, the mouse now designated as Mickey faces a former boyfriend of Minnie’s aptly christened under his first name. As with other production records, notations on voice recording for Disney’s short films in the 1930s have proven elusive. Keith Scott postulates that comic actor Sonny Dawson could have provided Mortimer’s dialogue (and cackling laughter) in the film.

The story directors of Mickey’s Rival, George Stallings and Earl Hurd, were rooted in New York’s animation scene; both worked at John Randolph Bray’s studio. Renowned as the inventor of the celluloid process of animation, Hurd formed a patent company with Bray for their technique, while also working on his Bobby Bumps series in the 1910s. Later, in the early 1920s, Stallings worked on a revived series of Colonel Heeza Liar cartoons, which combined live-action and animation. Both men worked as part of Disney’s story team by the mid-1930s, contributing to several Mickey Mouse films and Silly Symphonies. Clyde “Gerry” Geronimi, one of the animators on the film, had a similar background, and knew Stallings and Hurd from his time as an animator for Bray.

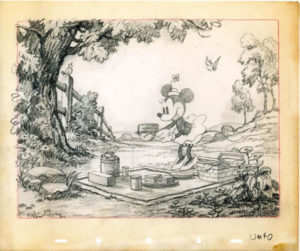

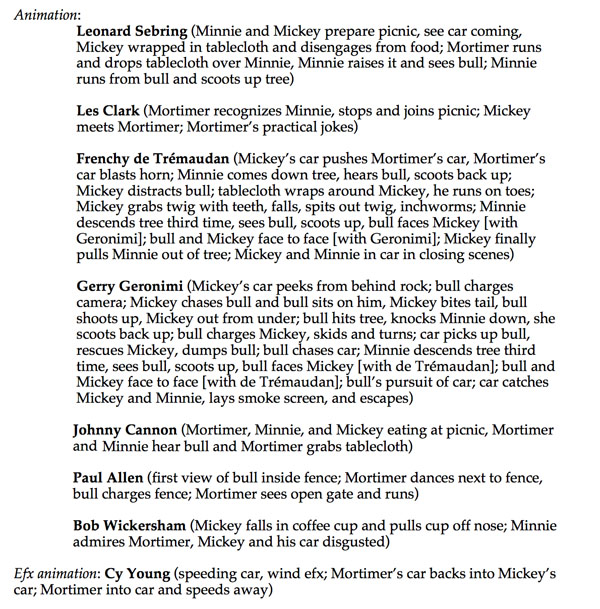

Director Wilfred Jackson (with assistant director Graham Heid) assigned the animators of different sequences throughout the film. Leonard Sebring animates the opening scenes of Mickey and Minnie preparing their picnic in the country, to the accompaniment of “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” (Leo Friedman/Beth Slater Whitson, 1910). Their romantic excursion is disrupted when a sports car speeds down the road with a velocity that wraps their picnic blanket around Mickey. Les Clark handles the scenes of Minnie introducing Mickey to Mortimer—“the perfect scream,” as she describes him. Clark continues to display his clear, direct posing/animation as Mickey endures his practical jokes. (Mortimer’s tall stature and intolerable nature might remind some viewers of Charley Chase’s character in the 1933 Laurel and Hardy feature Sons of the Desert.)

Director Wilfred Jackson (with assistant director Graham Heid) assigned the animators of different sequences throughout the film. Leonard Sebring animates the opening scenes of Mickey and Minnie preparing their picnic in the country, to the accompaniment of “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” (Leo Friedman/Beth Slater Whitson, 1910). Their romantic excursion is disrupted when a sports car speeds down the road with a velocity that wraps their picnic blanket around Mickey. Les Clark handles the scenes of Minnie introducing Mickey to Mortimer—“the perfect scream,” as she describes him. Clark continues to display his clear, direct posing/animation as Mickey endures his practical jokes. (Mortimer’s tall stature and intolerable nature might remind some viewers of Charley Chase’s character in the 1933 Laurel and Hardy feature Sons of the Desert.)

The scenes during the picnic in Mickey’s Rival were re-assigned late in production. The “semi-final” production draft, dated January 30, 1936, contradicts the credits shown on the exposure sheets. Dick Lundy and Dick Huemer were originally given different scenes in the sequence, but the exposure sheets, which seem to postdate the draft, indicate Johnny Cannon, Paul Allen and Bob Wickersham as their replacements. Cannon animates the three during the picnic, with Mortimer playfully using drumstick bones as castanets. Allen animates the first scenes with the bull—drawn with more naturalism than in Clyde Geronimi’s caricatured depiction of the animal—and Mortimer impressing Minnie, acting as a matador, using the picnic blanket as a cape to entice the bull behind his pen. Wickersham handles a nice bit of acting with Mickey, glaring at Mortimer as Minnie cheers, which turns to a nervous smile when she turns around to compliment his faux-bravado. Wickersham’s work continues when Mickey pouts and sits down next to his roadster.

The last half of Mickey’s Rival is mostly the work of Geronimi and “Frenchy” de Trémaudan. Geronimi animates all of the scenes with of the runaway bull after it escapes from the pasture, and Mickey’s car during the second half of the film. In later years, Ollie Johnston, an assistant animator at the time, recalled his involvement in clean-up work for Geronimi’s scenes. His work met with high esteem from director Wilfred Jackson and Geronimi. The assignment led to Johnston’s promotion as Fred Moore’s assistant by late March 1936. However, further research on the exposure sheets signifies that Johnston’s name is nowhere to be seen. Larry Clemmons is credited as Geronimi’s assistant on the documentation.

“Frenchy” de Trémaudan, one of the unsung animators at the Disney studio during the 1930s, is assigned to most of the scenes with Mickey and Minnie in the second half. (The production notes state a couple of scenes involving the bull and Mickey are jointly animated by Geronimi and de Trémaudan.) Trémaudan animates the final shot of the film, which displays subtle acting from the two characters. During the dissolve, as Minnie is seen seated next to an indignant Mickey, she keeps still as her eyes move slightly to him, awaiting a response without provoking further annoyance. After Mickey asks her if Mortimer is still funny, Minnie’s head stretches at the mention of his name, now repulsed after his act of deserting the two when the bull emerged from the gate. The two shake hands as the film irises out, as the tune “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” plays in the underscore. (The original ending had Mickey playing one of Mortimer’s gags on Minnie, with a trick extending glove.)

“Frenchy” de Trémaudan, one of the unsung animators at the Disney studio during the 1930s, is assigned to most of the scenes with Mickey and Minnie in the second half. (The production notes state a couple of scenes involving the bull and Mickey are jointly animated by Geronimi and de Trémaudan.) Trémaudan animates the final shot of the film, which displays subtle acting from the two characters. During the dissolve, as Minnie is seen seated next to an indignant Mickey, she keeps still as her eyes move slightly to him, awaiting a response without provoking further annoyance. After Mickey asks her if Mortimer is still funny, Minnie’s head stretches at the mention of his name, now repulsed after his act of deserting the two when the bull emerged from the gate. The two shake hands as the film irises out, as the tune “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” plays in the underscore. (The original ending had Mickey playing one of Mortimer’s gags on Minnie, with a trick extending glove.)

A couple of select shots are reused in Mickey’s Rival, such as the scene of Mickey’s car peeking from the rock (credited to Geronimi), which occurs after Mortimer’s horn scares it out of frame. The scene is later shown—set in a wider camera fielding—when it sees Mickey cornered by the bull against the tree, before springing to action. The bull skidding against the ground to reverse his path is used at least three times in the final sequence, alternating directional paths depending on its target, whether it is Mickey or his anthropomorphic jalopy.

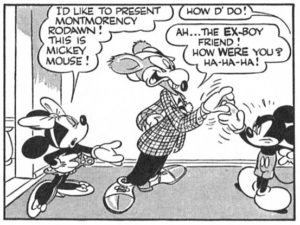

Though the film version of Mickey’s Rival was in production in late 1935, the character had earlier roots in the Mickey Mouse newspaper comic strip. Floyd Gottfredson created a precursor to the Mortimer character in his story “Mr. Slicker and the Egg Robbers”, which ran from September 22nd through December 29th, 1930. Coincidentally, Mr. Slicker robs the farm of Minnie’s uncle, named Mortimer. In early January 1936, before the release of the cartoon, Mickey’s Rival had its own comic-strip counterpart as a Sunday color story, which pitted Mickey and Mortimer against each other at Minnie’s house. After the film’s release on June 20th, Mortimer returned to Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse comic strip, renamed and updated as Montmorency Rodent in “Love Trouble,” which ran from April 14th through July 5th, 1941.

Later, in the 1970s, Mortimer made a comeback, again in print media. In these new stories, he would engage in heated altercations with Mickey at Slim’s Ice Cream, but would often be outsmarted by Goofy, much to his surprise and frustration. In the 21st century, Mickey and Mortimer’s conflicts continued in stories by Italian artist Andrea “Casty” Castellan. Mortimer finally emerged in animated form on the television shows Mickey Mouse Works and House of Mouse in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which used the revised Montmorency Rodent model. Most recently, Mortimer appeared in the Paul Rudish Mickey Mouse series in “A Pete Scorned,” in which he oversteps Peg-Leg Pete’s authority as Mickey’s tormenter.

Later, in the 1970s, Mortimer made a comeback, again in print media. In these new stories, he would engage in heated altercations with Mickey at Slim’s Ice Cream, but would often be outsmarted by Goofy, much to his surprise and frustration. In the 21st century, Mickey and Mortimer’s conflicts continued in stories by Italian artist Andrea “Casty” Castellan. Mortimer finally emerged in animated form on the television shows Mickey Mouse Works and House of Mouse in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which used the revised Montmorency Rodent model. Most recently, Mortimer appeared in the Paul Rudish Mickey Mouse series in “A Pete Scorned,” in which he oversteps Peg-Leg Pete’s authority as Mickey’s tormenter.

In place of an authentic production draft, J. B. Kaufman has lent the information of each individual animator’s work on Mickey’s Rival, based on his research for Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History. If you are able to purchase the book, please do so—the hard work of J. B. and Dave Gerstein is evident in its rich text, not to mention its wealth of artwork from the Disney Archives and various collections. Once I have finished the book, a full review will be written on Amazon, as promised.

NEXT WEEK: I will present another Mickey cartoon that I have wanted to profile for a while now …

(Thanks to J. B. Kaufman and Dave Gerstein for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

“In the 1980s, Mickey and Mortimer’s conflicts continued in stories by Italian artist Andrea “Casty” Castellan.”

Uh, here you are off by several decades. Andrea “Casty” Castellan was born in 1967 and didn’t start making Disney comics until 2003. (His comics are highly recommended, however — many of them have gotten excellent English-language editions by Boom! Kids and later IDW during the past decade. I consider him by far the best writer of Mickey Mouse comics these days.)

This breakdown gave me a new respect for Clyde Geronimi’s animation. I love that scene where the bull is running toward the camera, and the sequence in which Mickey’s care uses it’s tail light to enrage the bull. Likewise the scene where the little car revs up it’s rear wheels and sprays mud in the bull’s face. Frenchy’s scene of Mickey and Mickey making up and shaking hands is like wise a favorite. Who did Minnie’s voice in this one, Devon? Please do “The Worm Turns” some of these days.

Hiya Mark, glad you liked it! As for THE WORM TURNS, Hans Perk posted a draft of THE WORM TURNS on his blog (http://afilmla.blogspot.com/2006/12/prod-um47-worm-turns-incomplete_09.html), though it’s incomplete. I suppose if I gathered more information on the short, I could write about it, though I’d have to ask Hans first.

My copy of the Taschen book is on backorder at the moment with Amazon. I hope that is an indicator that it’s doing well. I also got my copy of the the recent Fantagraphic release Mickey Mouse: The Greatest Adventures which is another delightfully put together book. So many great Mickey books coming together recently.

I’ve done some research on Ancestry and Newspapers.com, and I have concluded that the same Sonny (alternately spelled Sunny) Dawson who voiced Mortimer in the short could have also been a performer in Snow White. Dawson played as a yodeling guitarist in a musical troupe called Stuart Hamblen and His Covered Wagon Jubileans, and he was branded as “America’s Champion Yodeler”. He did some yodeling for another film called Heidi, and he soon joined as a member of Skinnay Ennis’ band alongside Carmine Calhoun.

Dawson performed in the “Silly Song” in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, alongside other yodelers, including famed Disney sound man James “Jimmy” Macdonald and Freeman High.

One article mentions his birth name was Donald Palm.

(Also, to add to the confusion, there was another performer named ‘Little Sonny’ Dawson who performed with Glen Rice and his Beverly Hillbillies. But this one may have been a child in 1936, around 14 or 15 years old.)