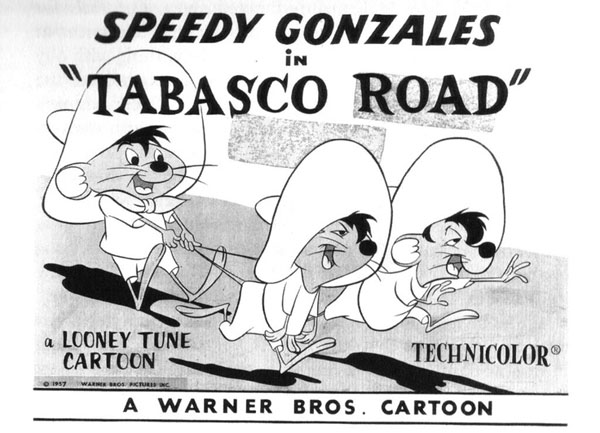

This week’s breakdown features an Academy Award-nominated cartoon with Speedy Gonzales, the fastest mouse in all Mexico!

Speedy Gonzales made his debut in an earlier 1953 McKimson cartoon, Cat-Tails for Two, as a mangy rodent with one gold tooth. Friz Freleng’s layout artist Hawley Pratt re-designed the character for the titular Speedy Gonzales, released in 1955. The moniker itself was sourced from a raunchy joke McKimson heard from a friend, and relayed to the studio to use as the name for a mouse character.

In his first appearance, Speedy is seen alone, against a pair of cats resembling George and Lennie from John Steinbeck’s novel Of Mice and Men. In Freleng’s film, the basic premise of many entries featuring Speedy sets a Mexican locale and features throngs of panicked mice —attired in sombreros and white shirts. In this cartoon, Speedy supplies wheels of cheese to the masses from a factory guarded by Sylvester. Tabasco Road marks McKimson’s return to the character, as re-designed by Pratt.

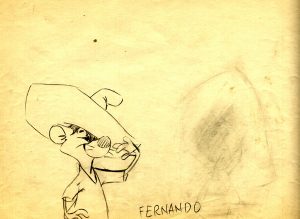

The opening scenes, which establish the Mexican nightlife—with layouts by Robert Gribbroek and backgrounds by Bill Butler—parallel the lives of the townspeople and the mice effectively, to a gentle rendition of Sebastián Iradier’s “La Paloma.” Inside a cantina, the bartender dries a glass, accompanied by a sped-up version of the “Mexican Hat Dance,” indicative there is a community of mice with their own “cantinita” inside his own establishment. The cartoon also relies on the consequences of social drinking, as Speedy tries to save his “muy loaded” amigos Pablo and Fernando from an alley cat—who, as difficult as the situation is, acts confrontational towards their enemies when inebriated—and bring them home safe. The urgency is implied through most of Speedy’s exits out of frame, where he leaves a small whirlwind behind him.

The opening scenes, which establish the Mexican nightlife—with layouts by Robert Gribbroek and backgrounds by Bill Butler—parallel the lives of the townspeople and the mice effectively, to a gentle rendition of Sebastián Iradier’s “La Paloma.” Inside a cantina, the bartender dries a glass, accompanied by a sped-up version of the “Mexican Hat Dance,” indicative there is a community of mice with their own “cantinita” inside his own establishment. The cartoon also relies on the consequences of social drinking, as Speedy tries to save his “muy loaded” amigos Pablo and Fernando from an alley cat—who, as difficult as the situation is, acts confrontational towards their enemies when inebriated—and bring them home safe. The urgency is implied through most of Speedy’s exits out of frame, where he leaves a small whirlwind behind him.

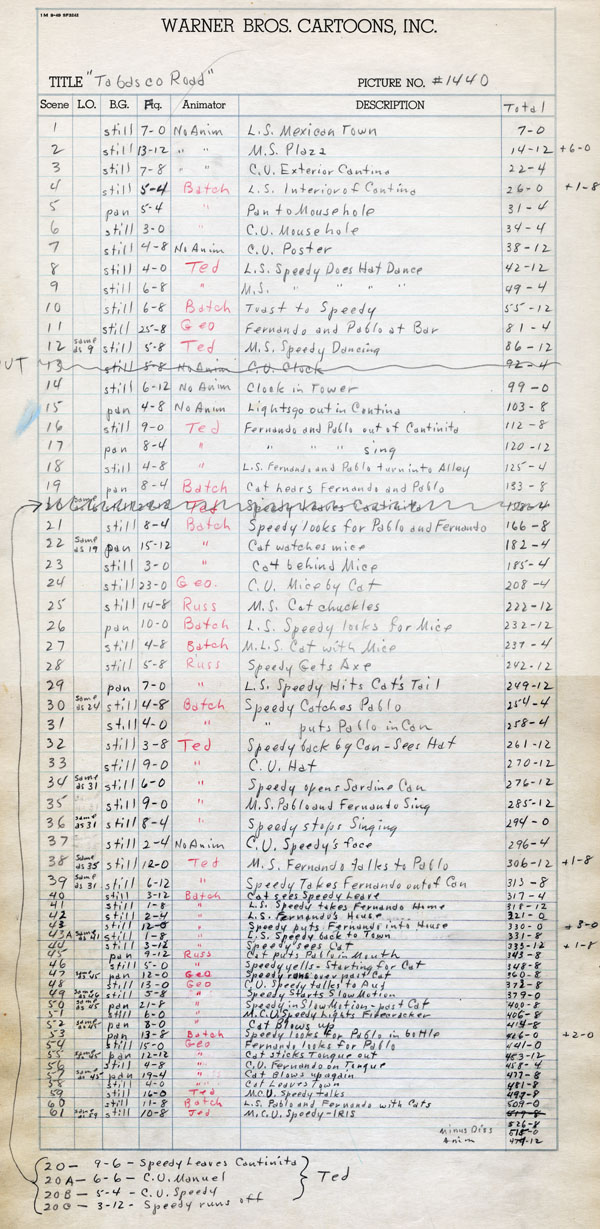

The animation in Tabasco Road is credited to Ted Bonnicksen and George Grandpre under the main titles, but there is also uncredited work by Warren Batchelder—Virgil Ross’ assistant for Friz Freleng—and Russ Dyson. Batchelder didn’t receive screen credit until the Foghorn ‘cheater’ film Feather Bluster (1958), and Dyson’s last credit occurred in Boston Quackie, released a month before this cartoon. It seems that this film might have been some of the last animation Dyson worked on at the studio; according to Tom Ray, Dyson committed suicide, and Ray was hired to replace him shortly after. Bonnicksen and Grandpre would be given their sole animation credits in McKimson’s subsequent films throughout the late 1957 and early 1958 releases.

By the early 1940s, Ted Bonnicksen was an animator at the Disney studio, working mostly on Donald Duck cartoons. Mike Kazeleh notes Ted Bonnicksen’s animation tended to be “professional but formulaic, and he seldom moved out of those few formulas,” when he later animated in other studios, such as Ed Graham’s Linus the Lion-Hearted, DePatie- Freleng, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts Animation, Filmation and Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat—after which he passed away from leukemia in 1972 at the age of 55.

By the early 1940s, Ted Bonnicksen was an animator at the Disney studio, working mostly on Donald Duck cartoons. Mike Kazeleh notes Ted Bonnicksen’s animation tended to be “professional but formulaic, and he seldom moved out of those few formulas,” when he later animated in other studios, such as Ed Graham’s Linus the Lion-Hearted, DePatie- Freleng, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts Animation, Filmation and Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat—after which he passed away from leukemia in 1972 at the age of 55.

Bonnicksen animates many significant scenes in the film, handling Speedy’s Mexican hat dance inside the “cantinita,” Speedy speaking with Manuel the doorman, and Pablo and Fernando’s drunken renditions of “La Cucharacha” as they wander into the alley, and later inside of a sardine can. Bonnicksen also handles the closing scenes with Speedy, after the alley cat flees out of town.

George Grandpre started at the Disney studios as a junior animator under Ben Sharpsteen’s supervision in the early ‘30s. He became a full animator when he moved to Walter Lantz’s studio. Grandpre moved to Harman-Ising, but shifted back to Lantz some time later in the late ‘30s. In the mid-‘40s, he went to John Sutherland’s studio to animate on the stop-motion Daffy Ditties. He migrated to Warners, where he was in charge of their in-between department before animating for McKimson. Grandpre animates Speedy chastising Pablo and Fernando for consuming more tequila inside the “cantinita,” and, in a brilliant sequence, Speedy’s slow-motion replay of switching Pablo with a small firecracker on the alley cat’s tongue.

Warren Batchelder’s animation in the McKimson unit, as Mike Kazeleh notes, “used plenty of overlap that gave an actual sense of where the motion was originating from.” Batchelder animates the alley cat seeing and pouncing after Pablo and Fernando, with the following scenes animated by Grandpre and Dyson. Scene 26 is ingenious for its use of conveying emotion as seen from behind the character, as Speedy sees his two amigos caught by their tails, about to be eaten by the alley cat off-screen. Batchelder animates another great moment when Speedy takes Fernando home, only to have him escape out of the window seconds later.

Warren Batchelder’s animation in the McKimson unit, as Mike Kazeleh notes, “used plenty of overlap that gave an actual sense of where the motion was originating from.” Batchelder animates the alley cat seeing and pouncing after Pablo and Fernando, with the following scenes animated by Grandpre and Dyson. Scene 26 is ingenious for its use of conveying emotion as seen from behind the character, as Speedy sees his two amigos caught by their tails, about to be eaten by the alley cat off-screen. Batchelder animates another great moment when Speedy takes Fernando home, only to have him escape out of the window seconds later.

Tabasco Road was nominated for an Academy Award, but lost to Friz Freleng’s Birds Anonymous, with Sylvester and Tweety. That film also relied on references to alcohol—a take-off on the support group Alcoholics Anonymous. Given the choices between the two cartoons, it may seem the Academy was more in favor of the Freleng cartoon, since it addressed similar addictions to alcoholic beverages, whereas McKimson’s film leans on the standard staples of inebriation comedy. Speedy’s next cartoon, Mexicali Schmoes (1959) would garner another Academy nomination, as did The Pied Piper of Guadalupe (1961), both directed by Freleng.

Enjoy, and drink responsibly!

(Thanks to Jerry Beck, Mike Kazaleh, Greg Duffell, Yowp and J.B. Kaufman for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

McKimson’s cartoons with the character are considered weaker overall than Freleng’s efforts using Speedy, but Bob held off pairing him with Sylvester until 1960, and in hindsight, the problems the studio had with formalistic efforts by then, “Tabasco Road” stands out for staying about as far away from the future formula as possible. It’s also one of those Warners efforts that reaffirms that the cartoons were made for both adults and the studio’s staff — Pablo and Fernando’s antics may have been funny to kids, but you don’t fully grasp the meaning of ‘liquid courage’ and appreciate the animated example of it until later in life.

The lyrics on “La Cucharacha” are amazingly close to the original for a G-rated cartoon.

Good to see a post-shutdown breakdown.

I’m not a fan of Ted Bonnicksen’s or George Grandpre’s work, at least when it comes to dialogue. Ted’s animation is too jerky- kind of like Gerry Chiniquy’s work but less appealing (and don’t get me started on how he drew Daffy in the Seven Arts shorts), and George’s work just kind of shudders in place. When they are animating gags, they’re okay, but I really don’t like their dialogue work.

Warren Batchelder gets a lot of praise, and indeed I prefer his work to Bonnicksen’s and Grandpre’s during this period, but my favorite animator during this time was Keith Darling, whose work came across as very Chuck Jones-esque.

oh my dear GOD! Had not seen this film in, literally, decades. A fun Treat to revisit. (We should all have a “designated driver” like our Hispanic Friend!) Now, again, WHAT was all the hubub (once upon a year) about “racism” in these films????

Really the most racist aspect of the Speedy cartoons was the bad Spanish in the dialogue. For Mexicans this was a moot point, since the Spanish dubs (done in Mexico!) just used regular Spanish with a “charro” accent.

For some reason, pastiching the French is Pepe le Pew cartoons is perfectly fine, while pastiching Mexicans in Speedy Gonzales cartoons is terrible and racist, even though the only real difference between the two is that Mexicans are of a different race. It’s a ridiculous double standard.

This is my fave speedy cartoon

The question is not so much who animated what in McKimson’s later cartoons, but more why would you want to know who animated what in McKimson’s later cartoons?

Because that’s the whole point of this “Breakdown” series, no matter the advancement of the animator’s talent.

I agree with Nic. Plus I really feel like you were a bit too harsh on Mckimsons animators with that statement.

I have to admit that I liked the slow motion sequence in this cartoon, and I think there was a similar such sequence in another of the SPEEDY cartoons. I’ve lately been almost wallowing in the latter Warner Brothers cartoons and, yes, in some ways, you can see that the animators were making the cartoons for their own amusement, even though Nickelodeon was regularly airing many of these, uncut as far as I know, on their afternoon LOONEY TUNES program. Times change and some of the situations probably would not run on TV these days, but hey, that is why we need a *REAL* cartoon network again, similar to how TCM ran things in the beginning, and I’m always glad for the LOONEY TUNES GOLDEN COLLECTION sets and wish that they were not discontinued. Cartoon comedy at most of the studios outise of Disney grew out of the gags of silent comedians and early comedies, where drunken behavior was mocked, along with all other aspects of human behavior that might be deemed anti-social, both then and now.

This was okay. Never knew McKimson did Speedy, but yeah, that’s def. him….I’m a defender of his and the later WB era stuff he did. This isn’t bad. You can have the endless Freleng Sylvester and Tweety’s if that’s your thing.