Today’s moonlighting animation artist in comics is the renowned Terrytoons and Hanna-Barbera animator Carlo Vinci!

Vinci was born in Yonkers, New York in 1906 as Carlo Vinciguerra to Italian immigrant parents, his father Andrea and his mother Maria. With a natural artistic talent from childhood, Vinci was awarded with a scholarship to the National Academy of Design when he graduated high school around 1924. As a student at the Academy, he attended intensive day and night classes where he studied art history, composition anatomy, perspective, still life and sculpture. (Many of Vinci’s life drawings from the Academy can be seen here.) Upon graduation in 1929, Vinci received the Silver Medal, the highest award for craftsmanship from the Tiffany Foundation Fellowship.

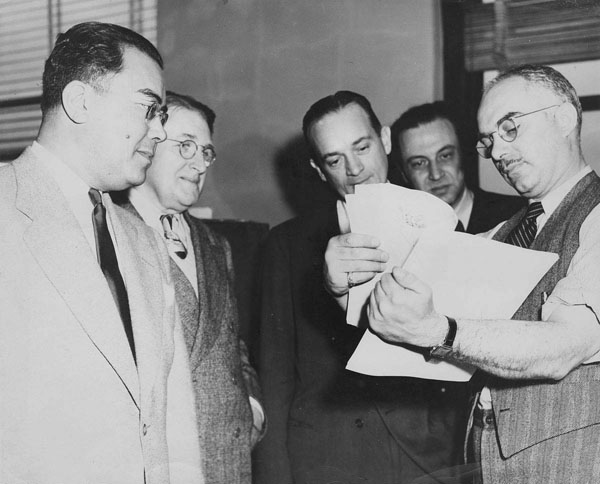

Vinci (right) flips a few scenes for Paul Terry, Bill Weiss and others at Terrytoons.

After graduating from the Academy, Vinci worked as a commercial artist. He painted murals, made stained glass windows and drew landscapes for homes and business offices. To support his family, he applied to the Van Beuren Corporation as an assistant animator in 1933. A year later, when Burt Gillett took over the studio, he recognized Vinci’s talents and promoted him to full animator. Later, Vinci taught a young, inexperienced Joe Barbera how to draw in-betweens. When Van Beuren closed in the summer of 1936, Vinci moved to Paul Terry’s studio as an animator. (Charlie Judkins states that his earliest Terrytoon was Kiko and the Honey Bears, released on August 21st.)

Vinci’s character animation, throughout much of his career, displayed a grace and dimensionality. As Milton Knight explained, his work is “largely the quick body motion into a slower, steady position before going into a quick move to the next slow. The body moves in reaction to the weight of the joint raised or moved.” For the Terrytoons, he was adept in animating jaunty movements to musical beats, and was often assigned to dance sequences—the most notable of these is the “Krakatoa Katie” song number for Mighty Mouse in Krakatoa, released in 1945. That same year, as reported in an April issue of the union newsletter Top Cel, he shortened his surname from Vinciguerra to Vinci (pronounced “Vin Chee”) to avoid the difficulty of pronouncing his birth name.

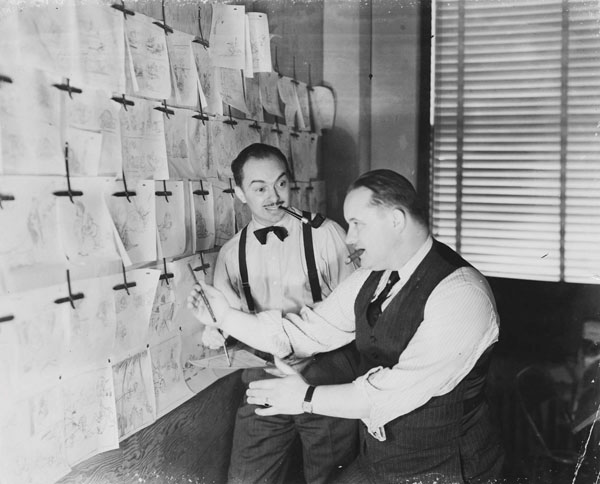

Vinci with Connie Rasinski

On May 16, 1947, shortly after Paul Terry’s refusal to negotiate a union contract with the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild over raises and benefits, Vinci was fired along with other animators, and a picket line formed two days after. The strike lasted several months; on November 15, Vinci and a few others crossed the picket line and returned to work at the studio. The strike was a source of animosity between Vinci and the remaining strikers for many years. He continued to animate for Terry until the mid-1950s.

In 1955, when Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera took over MGM’s animation department, Barbera arranged a job for Vinci at the Disney studio, to tide him over before his MGM stint. According to Floyd Norman, Vinci was mistreated at the studio simply because he was a New York import. In addition, management reprimanded him to slow down his productivity, since he was making the other animators feel inferior. Among the projects he animated was the Disneyland TV episode “Duck for Hire” (which aired on October 25, 1957).

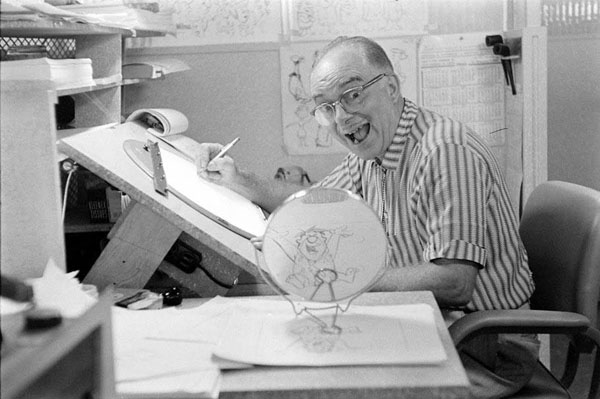

Vinci at Hanna Barbera

Soon, he joined MGM, animating for the Hanna-Barbera (for Tom and Jerry) and Mike Lah unit (on the Droopy cartoons). When Hanna and Barbera established their own studio specializing in cartoons made for television in July 1957, he joined them as one of their first key animators. He worked on Ruff and Reddy, Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, and The Flintstones. Though Vinci animated on Ralph Bakshi’s 1973 feature Heavy Traffic, Vinci continued to animate at Hanna-Barbera through the end of the ‘70s. In 1979, he retired from the animation industry, but continued his artistic endeavors as he drew, paint and undertook sculpture. He passed away in 1993 at the age of 87.

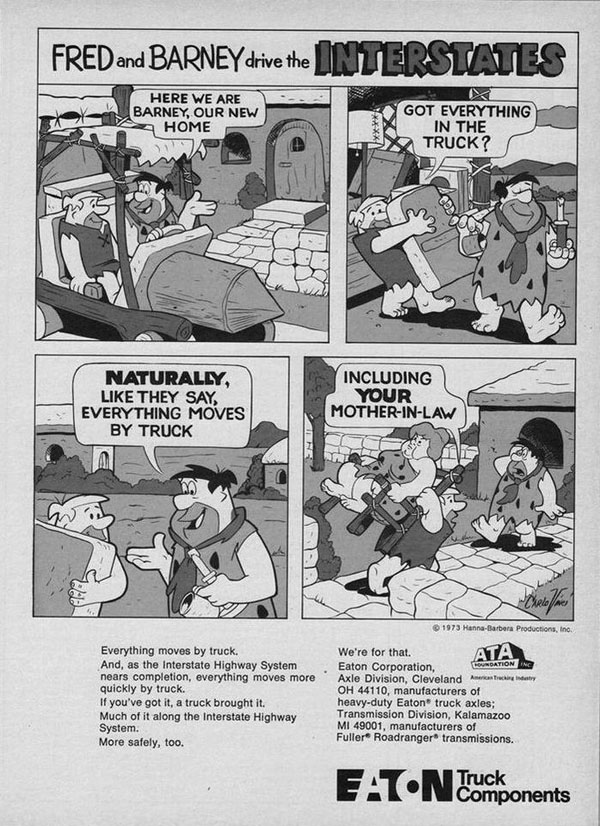

In the mid-1940s, Vinci drew comic books under the JCA (Jason Comic Art) label under a studio run by illustrator Leon Jason. Vinci’s stories are a small percentage from what has surfaced compared to other East Coast animators who also freelanced for JCA, namely Connie Rasinski and Marty Taras. However, Vinci drew comics with the Terrytoons characters for St. John Publishing on a regular basis in the mid-1940s and early 1950s. The drawing in his JCA and Terrytoons stories seems to be in the midst of an action in each panel, instead of holding a pose. As a fascinating curio, Vinci also drew a series of sponsored Flintstones comic strips for Eaton Truck Components, “Fred and Barney Drive the Interstates” in the early 1970s.

Here’s a selection of Vinci’s comic book work for your enjoyment!

• “Hawk-Sure the Detective and Whatsis”—Tick Tock Tales #2 (February 1946)

• “Waggin’ Weasel”—Cowboys n’ Injuns #2 (undated, 1946)

• “Pinky, Girl Detective”—Spooky Mysteries (undated, 1946)

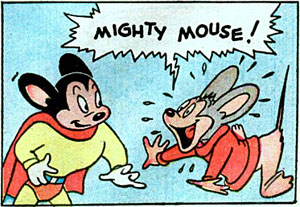

• “The Runt” (Mighty Mouse)—Mighty Mouse #14 (December 1949)

• “The Office Pest” (Little Roquefort)—Little Roquefort #3 (October 1952)

• “The Great Ice Box Mystery” (Dinky Duck)—Paul Terry’s Comics #95 (November 1952)

• “Sourpuss Tries Hard” (Gandy Goose and Sourpuss)—Paul Terry’s Comics #100 (April 1953)

• “TV Monstrosity” (Heckle and Jeckle) — Paul Terry’s Comics #111 (March 1954)

• “Off to the City” (Terry Bears)—Mighty Mouse #66 (October 1955)

(Thanks to Milton Knight, Charlie Judkins, Yowp, Thad Komorowski, Tom Sito and John Vinci for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Love that Hawkshaw the Detective parody (though they missed a good chance to call Whatsis “The Terrific Whatsis”)..

Carlo Vinci is possibly my favorite Hanna-Barbera animator. Thanks for today’s installment!

Didn’t Disney tend to put “outside” animators on commercials and the tv programme?

I am sure Vinci’s speed was resented, but could see the Disneyites saying it was a quality issue. I’ve always got the impression from reading, that Disney loyalists could look down their noses at the rest of Hollywood studios’ animation.

I’m guessing Morey Reden didn’t get very good reception at Disney either.

Glad I’m not the only person who thinks that Vinci was under-appreciated.

I wish the Disney hour DUCK FOR HIRE could be more widely seen now. Vinci’s timing and animation of the ducks is immediately recognizable, yet perfect for the job.

Vinci’s Terrytoons stories are colored storyboards of the cartoons themselves.