Today on Cartoon Research, a Yuletide gift to you all—an animator breakdown of an early sound Mickey Mouse cartoon! Trusted colleagues David Gerstein and JB Kaufman, authors of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History, have provided much of the information for this post.

With the premiere of Steamboat Willie at New York’s Colony Theater on November 18, 1928, its precise synchronization of sound effects and music to the animated action made the film a sensation. Since recording equipment had not been available to independent producers in Los Angeles, Walt Disney traveled cross-country to New York to set up a recording session for Steamboat Willie. Carl Stalling, then a renowned theatre organist in Kansas City, later joined Walt in New York with a pair of new musical scores for Plane Crazy and The Gallopin’ Gaucho, completed between May and June 1928, but released shortly after the success of Steamboat Willie. By April 1929, the Disney studio recorded their soundtracks in California with a Cinephone recording unit leased from Pat Powers.

The animation industry flourished in the wake of Steamboat Willie’s accomplishments, especially in New York, where the notion of animated cartoons as a lucrative business had arisen during the early teens. With only Ub Iwerks as his most experienced animator, along with fledgling staffers Les Clark, Wilfred Jackson and Johnny Cannon, Walt sought out seasoned animators in various studios during his visits to New York. In one instance, he visited Pat Sullivan’s studio in Manhattan and tried to hire away Otto Messmer, the chief architect of Felix the Cat. A world-renowned superstar in the 1920s, Felix was becoming overshadowed by the medium of sound and by Disney’s new starring character; producer Pat Sullivan balked at adding synchronized sound to the Felix cartoons. Messmer politely declined to join Disney, but other East Coast animators were eager to make the jump.

The animation industry flourished in the wake of Steamboat Willie’s accomplishments, especially in New York, where the notion of animated cartoons as a lucrative business had arisen during the early teens. With only Ub Iwerks as his most experienced animator, along with fledgling staffers Les Clark, Wilfred Jackson and Johnny Cannon, Walt sought out seasoned animators in various studios during his visits to New York. In one instance, he visited Pat Sullivan’s studio in Manhattan and tried to hire away Otto Messmer, the chief architect of Felix the Cat. A world-renowned superstar in the 1920s, Felix was becoming overshadowed by the medium of sound and by Disney’s new starring character; producer Pat Sullivan balked at adding synchronized sound to the Felix cartoons. Messmer politely declined to join Disney, but other East Coast animators were eager to make the jump.

When Ben Sharpsteen was hired in March 1929, he was a freelance commercial artist residing in San Francisco. He had worked at the International Film Service (IFS) and at Max Fleischer’s studio in New York, where his reputation as an animator was noted in a letter to Walt from one of Sharpsteen’s co-workers. A month later, Burt Gillett—a former Pat Sullivan employee—was on the payroll shortly after Walt’s visit to Sullivan’s studio. Before Sullivan, Gillett had animated at Barre-Bowers, IFS, Max Fleischer’s, and served as president of Associated Animators, an outfit that produced a series of Mutt and Jeff cartoons. The following June, James Patton (Jack) King joined the Disney studio as a veteran animator with previous experience at Barre-Bowers, IFS, and Bill Nolan’s studio in Long Branch, New Jersey.

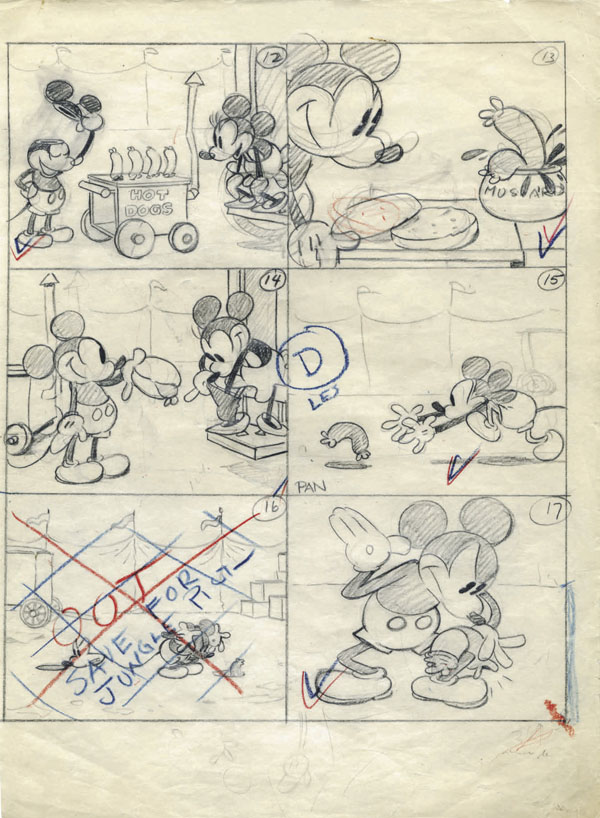

By mid-1929, Mickey Mouse had starred in eight cartoons, which notably told their stories almost entirely through pantomime; Mickey himself had no spoken dialogue. With The Karnival Kid, Walt Disney determined to make his latest Mickey a “talking picture.” As animated by Jack King, Mickey plays a hot dog vendor at a carnival fairground, first seen selling his wares as he shouts his first words uttered on-screen, “Hot dogs! Hot dogs!” He stands besides a platform, where a carnival barker exhorts a large crowd to see “Minnie, the Shimmy Dancer” for the cost of a dime. Mickey responds by heckling the barker in rhyme: “It’s a bum hooch dance—keep your money in your pants!”

While Mickey is known today for his falsetto voice, famously provided by Walt for many years, his few words of dialogue in Karnival Kid are an exception—rendered in a nasal baritone by an unidentified voice artist. In addition, subsequent films such as Mickey’s Follies and the “Minnie’s Yoo-Hoo” sing-along short—intended as a trailer for theaters that hosted Mickey Mouse Clubs in their matinees—also seem to use different people for the voice. (In the sing-along film, Mickey’s singing voice changes between one verse and another—nor is either verse the same unknown voice artist as Mickey’s Follies, though the animation is lifted from Follies.) In a 1969 interview with Carl Stalling, Stalling claimed to have provided the voice for Mickey in Wild Waves, but “all the animators were taking a shot at it, those who wanted to” before Walt Disney himself officially assumed the role.

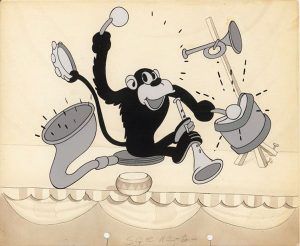

With a small staff of veteran animators from the East Coast, the Disney product gradually improved over the first year of Mickey Mouse cartoons, and The Karnival Kid shows off some striking innovations. Ben Sharpsteen animates the establishing shot of the fairgrounds, with a multitude of activity in the foreground and background with some impressive perspective animation of a cow lifted above the ground by balloons tied around her tail. Sharpsteen’s animation can be identified by certain drawing traits—he tended to draw smile lines on characters with a slight downward curve, and often, would animate happy characters with their eyes shut. In a later scene by Sharpsteen when Mickey taunts the carnival barker—a forerunner of comics co-star Kat Nipp, later introduced in 1931—it is abundantly clear he paid close attention to the lip sync.

With a small staff of veteran animators from the East Coast, the Disney product gradually improved over the first year of Mickey Mouse cartoons, and The Karnival Kid shows off some striking innovations. Ben Sharpsteen animates the establishing shot of the fairgrounds, with a multitude of activity in the foreground and background with some impressive perspective animation of a cow lifted above the ground by balloons tied around her tail. Sharpsteen’s animation can be identified by certain drawing traits—he tended to draw smile lines on characters with a slight downward curve, and often, would animate happy characters with their eyes shut. In a later scene by Sharpsteen when Mickey taunts the carnival barker—a forerunner of comics co-star Kat Nipp, later introduced in 1931—it is abundantly clear he paid close attention to the lip sync.

Burt Gillett started as an animator at the Disney studio, but only kept that position for a short period, being promoted to director a few months later. As seen in The Karnival Kid, Gillett’s footage seems crude in its drawing/movement, almost on the same level as other animated cartoons produced in the East Coast. In the two-shot of the romantic interaction when Mickey shouts commands at the “hot dogs”—shown as living creatures who lie down, sit up and bark on the grill—and the scene with Mickey and the chosen frankfurter, there are a few instances where Gillett’s animation intermittently slips in and out of held key poses, perhaps redrawn by Ub Iwerks. Gillett’s scenes also include a sequence with Mickey greeting Minnie, taking off his ears and tipping them like a hat, which inspired another milestone in the Mouse’s later career. It is said that this gag influenced Roy Williams, the “Big Mooseketeer” of TV’s Mickey Mouse Club, when he devised a pair of felt Mouse ears to be worn by each of the Club’s Mouseketeers. For The Karnival Kid, Disney and Iwerks undoubtedly cribbed the ear-tipping routine from Felix the Cat, who would often cordially tip his ears in the same fashion.

Regarding lifted material from previous shorts, the business with Mickey chasing down a disobedient hot dog and spanking it like a naughty child is recycled from the 1927 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon All Wet. Originally, as seen from story sketches, Mickey’s pursuit of the spanked hot dog extended further: borrowing from Alice Gets Stung (1925) and Oswald’s Africa Before Dark (1928), the hot dog was to run off and disappear into a burrow underground. Mickey squats by one of the burrow’s two holes, then removes his face and places it by the other hole. When the hot dog emerges from hole two near the disembodied Mickey’s face, he gets scared and dashes back through the burrow to hole one, where Mickey’s body catches him. This action was planned to occur before Mickey catches the hot dog and pulls down its “pants,” but ended up being dropped. A different finale made it all the way to animation before being excised: after the hot dog bites Mickey’s finger and runs off, Mickey was to follow the hot dog behind a bull’s-eye pitch target game, where Mickey would get struck by a baseball.

Regarding lifted material from previous shorts, the business with Mickey chasing down a disobedient hot dog and spanking it like a naughty child is recycled from the 1927 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon All Wet. Originally, as seen from story sketches, Mickey’s pursuit of the spanked hot dog extended further: borrowing from Alice Gets Stung (1925) and Oswald’s Africa Before Dark (1928), the hot dog was to run off and disappear into a burrow underground. Mickey squats by one of the burrow’s two holes, then removes his face and places it by the other hole. When the hot dog emerges from hole two near the disembodied Mickey’s face, he gets scared and dashes back through the burrow to hole one, where Mickey’s body catches him. This action was planned to occur before Mickey catches the hot dog and pulls down its “pants,” but ended up being dropped. A different finale made it all the way to animation before being excised: after the hot dog bites Mickey’s finger and runs off, Mickey was to follow the hot dog behind a bull’s-eye pitch target game, where Mickey would get struck by a baseball.

Later that night, Mickey arrives at Minnie’s window and serenades her, with the help of two alley cats. Ub Iwerks animates their yowling approximation of the 1903 barbershop standard “Sweet Adeline.” Originally, a close-up of Minnie powdering her face—singing “Love’s Old Sweet Song (Just a Song at Twilight)”—and Mickey sneaking by her window was meant to occur before the shot of Mickey looking at her in admiration.

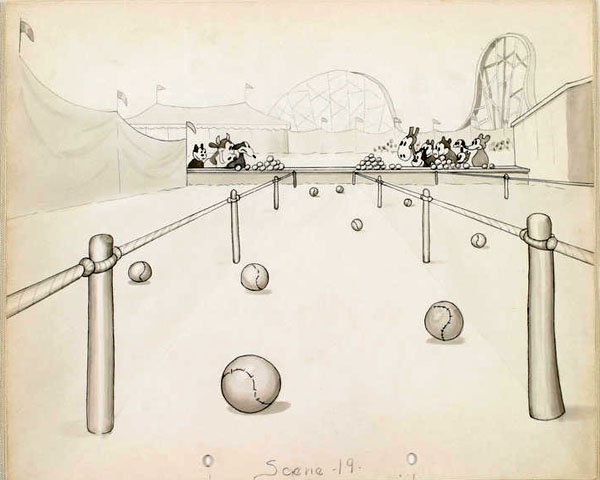

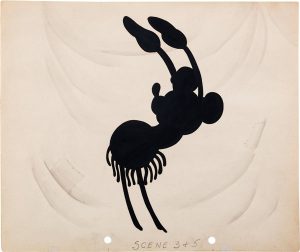

The cartoon’s ending was also heavily revised before release. In the original version, when the barker ends Mickey’s serenade by throwing his bed at him, Mickey was to ride away on the bed like a galloping steed. In the finished film, as animated by Les Clark, the thrown bed merely knocks Mickey dizzy. The closing scene of the disoriented Mickey seeing stars was originally animated for the omitted sequence of being crowned by the baseball, which was staged as a close-up (also assigned to Clark). Viewers will notice that Mickey grows drastically in size after the bed hits him.

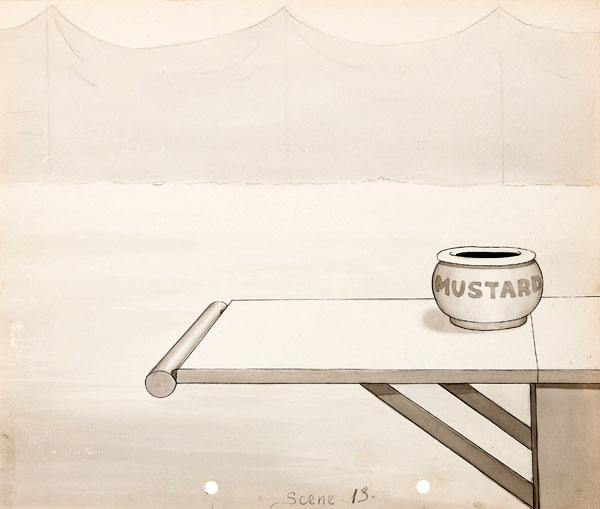

Production background from the deleted sequence of the target pitch game

Recent research by JB Kaufman has determined Ub Iwerks’ role in the Mickey Mouse cartoons released in 1929. Though Iwerks had played a dominant role in Mickey’s design, and in animating the bulk of Mickey’s earliest films, he did relatively little animation of the Mouse during the balance of 1929. Instead, Iwerks animated supporting characters while other animators concentrated on Mickey. Iwerks might have acted as a supervisor, guiding the different artists on their animation of Mickey.

Carl Stalling, later known for his tendency to utilize popular music in Warner Bros. cartoons, uses an appropriate selection of tunes for The Karnival Kid. Sir Julius Benedict’s “Carnival of Venice” accompanies the opening scenes of the carnival. “The Streets of Cairo,” a well-known popular melody even during the era of early sound films, is heard and sung with alternative lyrics during the scenes with Mickey selling his wares and the carnival barker extolling Minnie’s “hoochy-kootchy” act. In another example of inserting variant lyrics to a notable melody, Mickey continues to hawk his merchandise to the tune of “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean.” Edouard Poldini’s “The Dancing Doll” accompanies the following scene when Minnie comes out of her wagon and beckons to Mickey, while Léonard Gautier’s composition “Le Secret” plays in the underscore during the romantic sequences of Mickey and Minnie together. Stalling had previously used “Le Secret” as a theme for Mickey and Minnie in Plane Crazy (1928).

Carl Stalling, later known for his tendency to utilize popular music in Warner Bros. cartoons, uses an appropriate selection of tunes for The Karnival Kid. Sir Julius Benedict’s “Carnival of Venice” accompanies the opening scenes of the carnival. “The Streets of Cairo,” a well-known popular melody even during the era of early sound films, is heard and sung with alternative lyrics during the scenes with Mickey selling his wares and the carnival barker extolling Minnie’s “hoochy-kootchy” act. In another example of inserting variant lyrics to a notable melody, Mickey continues to hawk his merchandise to the tune of “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean.” Edouard Poldini’s “The Dancing Doll” accompanies the following scene when Minnie comes out of her wagon and beckons to Mickey, while Léonard Gautier’s composition “Le Secret” plays in the underscore during the romantic sequences of Mickey and Minnie together. Stalling had previously used “Le Secret” as a theme for Mickey and Minnie in Plane Crazy (1928).

After The Karnival Kid was shipped to Pat Powers’ office in New York on July 31, 1929, Powers was not impressed with the results—in particular, with the notion of Mickey speaking. Fearful that an English-speaking Mouse would not be commercially viable in foreign territories, Powers discouraged the idea in a telegram, which read: SUGGEST CUT OUT DIALOGUE…TRY NOT TO DEPEND ON IT. By the time his response arrived at the studio, however, Disney had nearly completed Mickey’s Follies, which carried the idea of a Mickey Mouse “talking picture” even further. In it, Mickey sings “Minnie’s Yoo Hoo,” animated by Ben Sharpsteen, containing the same intricate analysis of mouth action as his work on The Karnival Kid.

JB Kaufman compiled the animator credits embedded in our video (above) by using a set of story sketches that was salvaged by Floyd Gottfredson—then an in-betweener—when offices were shifted in the animation department in 1930. These sketches have animators’ names penciled on them for their designated scenes. A few months before Walt Disney passed away in 1966, after the story sketches were rediscovered, Walt called over Ub Iwerks and Les Clark to reminisce about the early period of the Mouse’s popularity. This conversation was publicized in the internal studio newsletter The Disney World.

I would like to announce on my Patreon page, there is an animator breakdown video on the holiday classic A Charlie Brown Christmas using the original 1965 broadcast. The video is offered at the $10 level and will remain on the page up until Christmas Day, so consider becoming a Patron if you would like to see it.

Happy Holidays to you all!

(Thanks to David Gerstein, JB Kaufman and Michael Barrier for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

“No one respects hot dog vendors more than I. They perform one of our society’s few worthwhile services.” — Ignatius J. Reilly, in John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces

Mickey may have borrowed a gag or two from his predecessor Oswald, but he was in turn imitated by Bosko in “Ups ‘N Downs” (1931) and Flip the Frog in “Circus” (1932). Meanwhile, over at Fleischer, Bimbo made his debut in the cartoon “Hot Dog” (1930) — but the only “hot dog” in it is Bimbo himself!

The idea of living hot dogs goes back at least as far as “Felix Comes Back” (1922). Felix doesn’t sell the hot dogs; they chase him (because he’s a cat), until he traps them in a hollow log and shoots them dead. I guess if hot dogs can live, they can also be killed. I’ll leave it to the theologians to debate whether or not they have souls.

“Minnie’s Yoo-Hoo” may have been the first ever cartoon theme song, but have you ever tried to sing it? It’s really hard!

I enjoyed this Breakdown — with relish! Hot diggity!

Always enjoy your articles and insights and you couldn’t have picked better resource consultants on the early Mickey cartoons than Gerstein and Kaufman.

That being said, here are a few of my insights: Mickey’s first word is “Hot Dog!” not “dogs” plural that is a common mistake made in many sources discussing this cartoon.

Mickey tipping his ears was actually an Iwerks gag from the Oswald cartoon Sleigh Bells (July 1928) and obviously got a laugh from audiences so is recycled here. The film also marks the first animated appearance of “pie-eyed” Mickey. It is also my understanding that the second half of the cartoon was printed on blue film stock to indicate night-time.

This information comes from my research for my book THE BOOK OF MOUSE (2013 Theme Park Press) where I did an annotated filmography of every Mickey Mouse cartoon.

Thanks for this post, Devon!

Two mysteries about this cartoon have intrigued me. Mickey’s line sounds to me like: “It’s a bum HORSE chance, keep your money in your pants!”, seems to make sense, comparing buying a ticket to see Minnie’s dancing to investing in a bad horse at the track. To call it a bum HOOCH chance, just doesn’t seem to make sense. The track recording on the old Cinephone system is not the clearest, at any rate.

Also, what originally happened in Les Clark’s scene where Mickey chases the hot dog on a pan, and then grabs it. There seems to be a jump in the action, just as the hot dog begins to scream at being grabbed. You can hear a splice go by on the sound track here as well. Any theories?

Thanks, Mark

When adding a soundtrack to “Plane Crazy”, it included a vocal of Minnie saying “Who, me?” since her mouth movements already made the statement clear. An earlier Mickey short, “The Barnyard Battle”, also had synched dialogue (“Company-y-y-y-y! Forwa-a-a-a-ard! MARCH!”).

Looking at Burt Gillett’s animation in this and “The Plowboy”, I’d say his style of drawing and timing was more looser and cruder than the other animators, which made it all the more surprising when I saw that he did the close-up of Mickey preparing the weenie instead of Iwerks. Maybe Burt was drawing from his layouts?

I’m also surprised that Iwerks animated only one (admittingly long) scene here. Perhaps he was busy preparing to be the director and head animator of the Silly Symphonies (in addition to drawing publicity art and animation layouts).

Re: “Also, what originally happened in Les Clark’s scene where Mickey chases the hot dog on a pan, and then grabs it. There seems to be a jump in the action, just as the hot dog begins to scream at being grabbed. You can hear a splice go by on the sound track here as well. Any theories?”

Maybe that’s where the scene where Mickey removes his face was supposed to go?

Also wait, so Carl Stalling didn’t voice Mickey in this short?

As to that link to the Charlie Brown Christmas video… I thought I was paying for a DVD/video- but it was just a fee to see the presentation online. No way to download or copy it. Glad to see it. But thought I was getting a copy! MH

(The CR interface isn’t letting me reply to individual messages today, so here’s a group reply… I hope people see it.)

Jim Korkis: Oswald also tips his ears to a girl in the even earlier ALL WET (1927). But Felix actually did perform the action first—for instance, in TWO-LIP TIME (1926).

As for Mickey’s pie-eyes, he actually has them first in THE PLOWBOY (1929), which predates THE KARNIVAL KID.

Mark Kausler: Going by an original 1929 story outline at Disney, Mickey says “It’s a bum hootchie [sic] dance…” not “horse chance” or “hooch chance.”

Brandon: Stalling more than once mentioned he’d provided Mickey’s voice, leading a lot of Gen X scholars—myself included—to presume Stalling must have provided the lower voice that pops up a few times in 1929.

But conventional wisdom isn’t always right. The others and I were overlooking the 1969 Barrier interview, in which Stalling very explicitly describes WILD WAVES as the only one, and even quotes one of its lines of dialogue (“Aw, shucks, that’s nothin’!”). As Stalling himself points out, Mickey’s voice in WILD WAVES is a falsetto, suggesting very strongly that Stalling didn’t provide the earlier lower voice.

We can’t be 100% sure, but AFAIK that’s the present state of research.

I heard that there’s a chance the Charlie Brown video might be coming here. PLEASE MAKE IT HAPPEN?! I’ve been wanting to know who animated these scenes. So please, make my Christmas happy and put it on here.

What’s Next?

The alley cats are definitely imitating the vocal stylings of the popular vaudeville team Shaw & Lee.

Did anyone see scene 16 on the storyboard and was reminded of Africa Before Dark (1928)? Obviously, Disney recycled some of his gags from the Oswald shorts, but I’ve never seen that gag in a Mickey Mouse cartoon (at least none I can remember).

Thanks, Devon – your Cartoon Research posts are outstanding!

Wow! This article is VERY informative! There’s one thing missing however that I’d love to know, and I’ve actually been trying to find for at least 15 years.

What is the song that plays while Minnie is selecting her hot dog? Roughly 3 minutes into the short. I’ve been searching for this song for years, it’s the epitome of Iwerks Mickey to me, and is the first thing I think of when someone mentions the classic Mickey shorts. That song.

Hey according to Wikipedia there is an “after credits” scene with Pete. As it’s not in the actual cartoon, is there evidence of something like this being cut before release?

In the close-up scene where the weenies bark and scratch themselves, there are ascending wavy lines to indicate heat, or maybe steam, and they flicker since they appear on alternating frames- each frame with the lines is followed by one with no lines. I’m not sure what they were going for here, it’s an experiment that doesn’t really work, but it was left in anyway. I’ve seen something similar done with vibrating harp strings in Sy Young’s one-shot Mendelssohn’s Spring Song, and it works quite well; the strings just sort of shimmer.