This week’s breakdown features Hanna and Barbera’s famous cat-and-mouse duo!

The cat-and-mouse rivalry in Bill Hanna-Joe Barbera’s directorial debut, Puss Gets the Boot, was initially met with contempt by producer Fred Quimby for its stale concept. The cat and mouse’s portrayal in more conventional fare depicts them as hunter and prey. Hanna and Barbera brought more personality to the match, portraying them as rivals where Jasper, named so in this cartoon, torments the little mouse for his own amusement. In retaliation, the rodent boldly manipulates different situations to the feline’s disadvantage, as he faces ejection by his owner if she catches him causing another broken mess. The dynamic proved successful with Puss Gets the Boot’s February 1940 release and Oscar nomination.

The award was given to Rudy Ising’s The Milky Way, a cartoon more in tune with Disney’s lavish Silly Symphonies. Soon after, animation studios diverted from this pattern in favor of brash, vigorous star characters. Hanna and Barbera directed cartoons without the cat-and-mouse duo, under producer Fred Quimby’s orders to use different characters (Swing Social, Gallopin’ Gals, The Goose Goes South, Officer Pooch). The results were not as captivating. When a letter from a major exhibitor demanded more “cat-and-mouse” cartoons, story work on their second entry, The Midnight Snack, was underway by April 1940. The cat and mouse team became officially known as Tom and Jerry.Bill Hanna had studied journalism and engineering in college, and worked as a structural engineer before getting into animation. With no formal art training, he started with Harman-Ising’s studio, in its earliest days, as a cel washer and janitor. He was eager to help with any aspect of production, though he never animated. Rudy Ising liked his enthusiasm and let him help with stories on the early Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. Hanna soon became the head of the inking/painting department. When Leon Schlesinger broke his business relationship with Harman and Ising, Hanna moved, with the two producers, over to MGM, where he rose through the ranks, serving as a timing director for the 1936 Happy Harmony To Spring.

Due to the cost overruns on their bountiful cartoons – something Quimby often berated Harman over — MGM decided to form their own animation studio, and canceled their contract with Harman and Ising, around mid-1937. Hanna, along with Friz Freleng and animator Bob Allen, were directing a series based on the Captain and the Kids comic strip. After financial difficulties and intermittent shutdowns, Harman and Ising filed for bankruptcy in July 1938. They went on the MGM payroll in October of that year. They were both granted their own individual contract.Joe Barbera prepared for a career in banking but devoted more energy to selling magazine cartoons on the side. After a week inking/painting cels at Fleischer’s studio, he moved to Van Beuren as an in-betweener. Animator Carlo Vinci coached him through the process. Soon, Barbera served as an animator. He often took the subway to sell illustrations to Colliers magazine during his lunch break. His comedic knack promoted him to the story department. When the studio closed, he found work at Terrytoons as a story-man. He co-wrote the surreal Pink Elephants with director Dan Gordon ─ arguably the standout out of Terry’s 1930s cartoons.

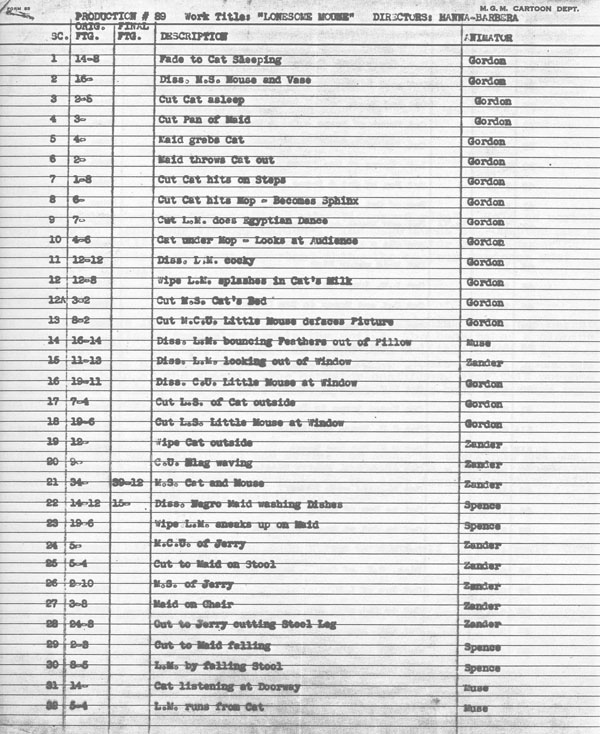

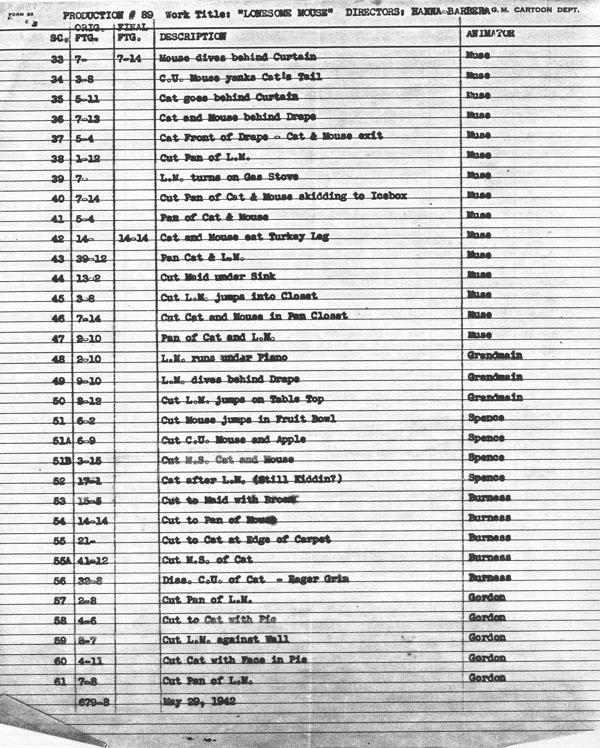

Two animators credited in the draft for Lonesome Mouse, Jack Zander and George Gordon, worked at Terrytoons with Barbera. The three re-located to MGM when its cartoon studio opened. Bill Hanna first knew Barbera as an animator during the Captain series, but when Joe became a gagman for Freleng, Hanna admired the mood and expression in his story sketches. Since Hanna felt a lack of confidence in his drawing, he decided to team up with Barbera under Rudy Ising. After Freleng departed the studio in April 1939, Fred Quimby gave the two their own directorial unit. Puss Gets the Boot was the result of an edict to produce many cartoons per year for the studio, since Harman and Ising could not. Despite Hanna and Barbera working under his auspices, Rudy Ising is given sole credit in the finished cartoon.

Two animators credited in the draft for Lonesome Mouse, Jack Zander and George Gordon, worked at Terrytoons with Barbera. The three re-located to MGM when its cartoon studio opened. Bill Hanna first knew Barbera as an animator during the Captain series, but when Joe became a gagman for Freleng, Hanna admired the mood and expression in his story sketches. Since Hanna felt a lack of confidence in his drawing, he decided to team up with Barbera under Rudy Ising. After Freleng departed the studio in April 1939, Fred Quimby gave the two their own directorial unit. Puss Gets the Boot was the result of an edict to produce many cartoons per year for the studio, since Harman and Ising could not. Despite Hanna and Barbera working under his auspices, Rudy Ising is given sole credit in the finished cartoon.

Hanna-Barbera’s success with the Tom and Jerry series allowed them to handle the series exclusively, a deviation from the standard in other studios, where different units had to make cartoons with their star characters, like Bugs and Porky at Warners. The duo established a beneficial production method. Bill’s background in music and Joe’s comedic sensibilities adequately complimented each other. Hanna timed the cartoons on bar sheets, while Barbera drew story sketches and supplied many of the gags. They timed the story sketches and shot them as a pose reel to evaluate the results. Much like the silent film comics, Bill and Joe were painstaking in their timing, often requiring animators to redo their scenes to emphasize a different expression or enhance the timing.

The early Tom and Jerry cartoons’ deliberate pace stemmed from Ising’s Disney influence. The May 29, 1942 date on this draft indicates that Avery’s September 1941 arrival had a slight effect on their accelerated pacing, but not to a substantial degree. Being natural enemies, Tom and Jerry’s cartoons demanded a brutal quotient of violence. Their aim was to inflict pain on each other in preposterous ways, carried over from the climactic beatings that Popeye and Bluto endured in the Fleischer cartoons. Silent and sound film comedy also influenced the violence, in that the films displayed more emphasis on the injury and the suffering on the affected. The tenth entry, The Lonesome Mouse, diverts from this formula. Aside from Tom and Jerry having dialogue, they realize their dependence on each other, despite their rivalry. Nowhere is their chemistry better explained than when an off-screen voice (supplied by radio actor Harry E. Lang) informs Jerry, “You can’t live with him, but there’s no fun without him.”

The animators that worked on the Tom and Jerry cartoons have distinguishable stylish earmarks that are easy to decipher. George Gordon, one of Barbera’s fellow animators from Terrytoons, draws the characters with a Harman-Ising appeal. Gordon’s scenes with Jerry display great usage of weight and momentum, where he takes advantage of Jerry’s lack of balance with his small stature (scene 12A: where he picks up the match, and scene 59, after he kicks Tom into his “re-ward”). Jack Zander, another former Terry artist, tended to draw the characters more bulkily – in addition to giving Tom thick eyebrows – but his rubbery animation is fun to watch.Ken Muse served as an assistant to Preston Blair on Disney’s Fantasia, and animated several early forties Mickey Mouse entries. He left after the 1941 strike and moved to MGM, animating for Hanna-Barbera up to their television cartoons in the late ‘50s. Muse’s first half of Tom and Jerry’s contrived chase demonstrates a dimensional and solid construction that reflects his Disney background. Irv Spence’s loose animation emerged from the later Ub Iwerks ComiColors, like Simple Simon and Little Boy Blue. He isn’t assigned many scenes in The Lonesome Mouse, but his sequence in which Tom becomes too enthusiastic in chasing Jerry has some great timing and wild drawings.

Pete Burness, like Zander, started his career with the short-lived Romer Grey studio, and migrated to Ted Esbaugh’s. He worked at the Van Beuren studio before joining Harman and Ising at MGM. Burness’ animation often had the characters pop from pose to pose, creating a staccato feel to the movement, especially in scene 53, with Tom continually being struck by his owner’s broom. It’s interesting to see Al Grandmain given three shots of character animation in The Lonesome Mouse, with a style that partly resembles Zander’s drawing. It proves that Grandmain was not just an effects animator, as is often assumed.

Enjoy the mayhem in this week’s breakdown video!

(Thanks to Keith Scott and Frank Young for additional help).

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

These sequences animated by a single animator are sure long!

“Puss Gets the Boot, was initially met with contempt for its stale concept.” By whom? I’ve read two contemporary trade reviews and they were positive.

Yowp, now I clarified that sentence above – Fred Quimby was not enthused.

After reading the Wikipedia full descriptive plot outline of this cartoon, I find it hard to keep up with who is voicing what. Sometimes, it seems as if Lillian Randolph is also taking part in some of Tom’s “utterings”, like his mock crying jag to show the lady of the house that Jerry has been mutilated in the most gruesome of fashions. Oh, and it is always interesting to hear Scott Bradley’s scoring “keep up with” the wild antics going on throughout!

Oh and, not meaning to take anything away from this breakdown, but thanks to whomever is writing up full descriptive plots for our favorite major studio cartoons. Please continue to do so for so many of the other MGM classic cartoons, from Harman/Ising through Tex Avery and Dick Lundy, etc. I like reading ’em for reference, especially since I don’t quite recall ever seeing this cartoon, unless it was part of the TOM & JERRY FESTIVAL OF FUN that toured movie theaters during the mid-1960’s. Sure wish that another such toon compilation would happen like that. Hey, they bring back old movies for a brief theater run. Why not a good old-fashioned toon run, this time with original opening credits and all that!

I think this is the only Tom and Jerry cartoon with a WWII reference.

“Yankee Doodle Mouse” is heavily influenced by WWII homeland defense in the U.S., beginning with a “Cat-Raid Shelter” and some mock propaganda posters

But yes, this cartoon is the only one that directly references the enemy Axis powers.

Well, there is Yankee Doodle Mouse, which opens and closes with very specific WWII references, and has a few scattered in between. In general, though, the Tom & Jerry cartoons didn’t make topical references to the same extent Avery cartoons did, to be sure.

Nope, Yankee Doodle Mouse is full of WW 2 references. Originally there was a scene in which Jerry forced Tom to lick defense stamps and paste them in a savings book, but that was taken out of the negative for re-issue.

An original layout drawing of a background for that scene was posted on the Cartoon Network Department of Cartoons website years ago. http://web.archive.org/web/20020205234732/http://www.cartoonnetwork.com/doc/tomjerry/bg/bg4/bgpg001.html

MGM’s godawful ugly poster art for its cartoons is an ongoing source of fascination to me. That on the earlier “Lonesome Mouse” poster has to rank among the very worst.

And I thought Republic had some bad poster art! As off-model and wonky as that first poster is, at least MGM gave Hanna and Barbera credit on it, before Quimby would hog the poster credit (as in the second poster).

Please someone! What — if any — is the connection between animators Dan Gordon, and George Gordon? Any info would be helpful.

They were brothers.

How do you decide on which cartoons to put in a Baxter’s Breakdowns post?