Today’s breakdown is an MGM cartoon featuring Barney Bear!

The MGM one sheet poster drawn by Bela Reiger.

By the mid-‘30s, as MGM discontinued their Happy Harmonies series, they attempted to rectify their lack of continuing star characters by adapting newspaper comics, such as Rudolph Dirks’ Captain and the Kids and Milt Gross’ Count Screwloose. While both series were generally amusing, they were too brief to make a lasting impression. The Bear That Couldn’t Sleep, released June 1939 and made under Rudy Ising’s unit, featured an unnamed bruin and his failed attempts to hibernate during the winter.

The bear’s sleepy nature is often attributed to actor Wallace Beery’s burly physique and to screen comedian Edgar Kennedy, who is regarded for his pivotal role in frustration comedy in several classic Laurel and Hardy films and RKO’s Average Man series. However, producer Fred Quimby, and few of Ising’s colleagues, agreed that the lumbering bear was actually based on the director’s own tired disposition. Ising was known for his “sleeping problems;” while at the Disney studio, he was fired on March 1927 for sleeping while he operated the animation camera.

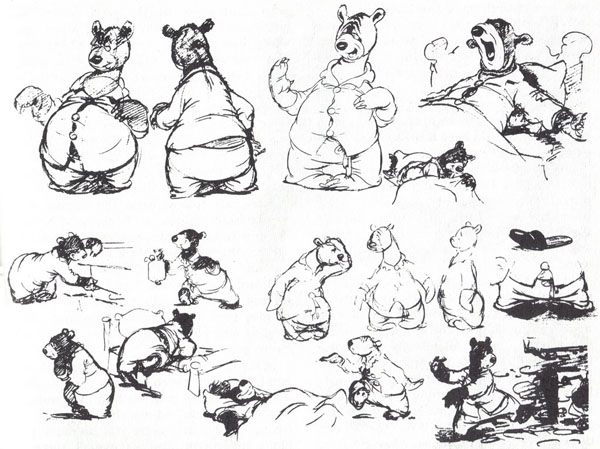

In Ising’s approach to the character, Barney plays foil to the conditions that occur around him. He is often overshadowed by the side characters’ actions, like the titular beavers in this cartoon. Ising hadn’t adapted to the brash style of characterization that emerged in the early 1940s; therefore, Barney’s personality was unsuitable to breakneck violence. Ising continued to direct the Barney Bear series until 1942, when he left MGM to head the Army Air Force’s animation unit. George Gordon briefly handled the series, but left the studio in 1943. At that time, MGM ceased production of Barney Bears altogether. During the hiatus, the character continued in a different medium, as Carl Barks reluctantly wrote and drew stories of Barney (with co-star Benny Burro) for Dell’s Our Gang Comics from 1944-47, although Gil Turner ultimately scripted the stories during the last period.

Barney’s series revived when Mike Lah and Preston Blair began directing as a team in early 1946, though Lah claimed to have directed an earlier 1945 entry, The Unwelcome Guest, which is often credited to Gordon. The series ended abruptly, as the Blair/Lah unit dissolved after three cartoons, due to cost overruns and an executive decision to reduce directorial units.

Dick Lundy filled Tex Avery’s directorial slot when he left the studio on a sabbatical around May 1950. Lundy admired Barney’s affable personality and wanted to differentiate from the frenetic pace of Avery and Hanna-Barbera’s cartoons by loosening the speed. The resulting films show these more laconic ambitions, but there is some great timing and humor in the cartoons, often in the Avery vein. Wee Willie Wildcat (1953), Cobs and Robbers (1953) and The Impossible Possum (1954) are standout entries that are perfect for a character like Barney. When Avery returned to MGM around October 1951, he resumed directing, and the studio produced no more Barney Bear cartoons.

While Bear and the Beavers promises great comic potential, it is marred by Ising’s Disney-esque approach to story and timing. The cartoon details its plot through the unnecessary courtesy of storybook pages. The cartoon could easily ensue without them, since there is primarily no dialogue. The cartoon’s climax is fairly weak: after Barney deprives the beavers of their firewood, they demolish Barney’s home. Sluggish timing is the culprit. If such an action played to an exaggerated degree, instead of the organized fashion, as seen here, the results would have paid off better. Scott Bradley’s musical score is nicely done, despite the cartoon’s shortcomings.

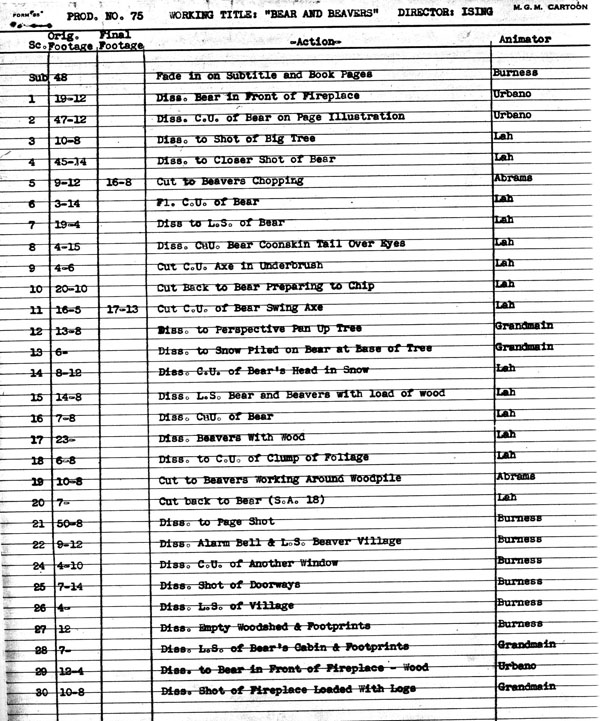

Ising casts his character animators for The Bear and the Beavers in individual sections, while Al Grandmain handles many of the effects. Pete Burness tackles the beavers discovering their missing woodpile and their planned vengeance outside of Barney’s house. Fascinatingly, Burness is also credited with the storybook transitions. In addition, Carl Urbano animates Barney inside his home, basking in warmth and his reactions to (and the aftermath of) his destroyed home. Mike Lah animates Barney’s failed attempts, consternation and his plans to steal the beaver’s firewood. Paul Sommer animates the meatiest portion of the cartoon — the beavers marching over, brandishing weapons, and their destruction of the bear’s abode. Ray Abrams animates only two shots in the cartoon, both involving diligent activity as the beavers stock up on firewood.

Enjoy this week’s breakdown video!

(Thanks to Mark Kausler, Michael Barrier, Frank Young and Thad Komorowski for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

While there are some good laughs early on (the bit with the axe, for instance), I agree with you that the slow pacing puts a damper on things. While Ising’s imitation of the Disney style in terms of pacing and dramatic presentation is inappropriate for the subject matter, the irony is, had Disney made the cartoon, it would have certainly been funnier, or at least better paced. Consider “Chip N’ Dale”, made four years later, which has a similar premise. While not as wild as the Warner or Avery shorts, it’s still a laugh riot.

The only time I’ve seen Benny Burro was in the classic MGM Cartoon Little Gravel Voice and there wasn’t another donkey star for MGM who starred in The Tree Doctor and Intertube Antics?

Yep. That donkey was created by George Gordon for those specific cartoons. They aren’t connected in any way, however.

The poster art for the cartoon’s climax is more energetic than the climax itself. It also wouldn’t have been as noticeable if this had been a 1939 MGM cartoon, but by 1942, even Disney had sped up the timing on their cartoons to reflect the trends towards more energetic comedy. As Michael Barrier noted about Hugh Harmon’s later MGM efforts, the desire here isn’t as much to entertain the audience as it is to impress the audience with the animation skills and the film editing techniques.

Yep, that’s as deadly-show as I remembered. Mike Lah’s animation is great, though.

er, deadly-SLOW. Danged autocorrect!

I was quite surprised by that opening theme music – very unusual, without one of the standard MGM fanfares over the lion logo.

Interesting group of animators. Michael Lah got a lot of footage on this one, but none of it – with the possible exception of the shudder take in scene 9 – looks like his later animation for H-B or Tex Avery. Neither does any of the animation in the other Rudy Ising/Robert Allen or George Gordon -helmed cartoons where he was given screen credit. Did he make a conscious decision to change to a much more simplistic style of drawing when he moved to Bill and Joe’s Tom & Jerry unit, or were his earlier drawings heavily cleaned up by assistants?

Michael Lah and Carl Urbano (as well as Al Grandmain, though I would assume he wasn’t tied to a particular director/unit) continued in Rudy Ising’s unit for a while, receiving screen credit on “Wild Honey” and “Chips Off The Old Block” respectively, then both were credited on George Gordon’s “The Stork’s Holiday”. (I’m assuming Gordon took over the Ising unit)

Pete Burness must have left Ising’s unit after his work on this cartoon was completed as a few scenes of his animation crop up on the contemporary “Puss ‘n’ Toots” and he would stay in the Hanna-Barbera unit for the next few years. Paul Sommer doesn’t seem to have any MGM on-screen credits. Ray Abrams worked on Hugh Harman’s “The Field Mouse” the previous year, then of course became one of Tex Avery’s mainstays of the ’40s. According to Thad’s MGM Cartoon FIlmography (http://www.whataboutthad.com/mgm-cartoon-filmography-by-production-number/) “The Bear and the Beavers” was after Harman’s last cartoon and before Avery’s first, so I guess Abrams was moved into Ising’s unit to give him something to do while the changeover happened.

I believe Benny Burro appeared with Barney Bear in “THE PROSPECTING BEAR”, a cartoon that I think is also included in the feature-length theatrical film shorts compilation called “THE TOM AND JERRY FESTIVAL OF FUN”. The climactic portion of “THE BEAR AND THE BEAVERS” was an unusual montage sequence for MGM. The screen wasn’t split so that we see the beavers coming at Barney from all sides; the sequence shows the distruction that all the beavers are doing super-imposed over each other–am I right? The only other time I’d seen that kind of technique was in a Warner Brothers cartoon that I think is called “A STAR IS HATCHED” to show the passage of time as we see the chick’s “legs” walking, walking, walking, with the mames of the states she’s tried to hitchhike through and other visuals flashing over the image of her walking wearily along the road, hoping for a lift. I hope I’m right, here, but I do remember seeing that kind of trick used for the climax here and I wondered why.

Actually, to my memory, the most visually striking and violent of the Ising BARNEY BEAR cartoons was “WILD HONEY” once the swarm of bees realizes that Barney Bear tricked them with a mechanical queen bee leading them in a congaline and, ultimately, self-distructs. The bees morph into the shape of a bomber plane, dropping as bombs and exploding across Barney’s back as he tries in vain to get away. That’s as wild as it got, unless you want to include Ol’ Bruin’s harrowing descent in a failed little airplane in “FLYING BEAR”.

So Little Gravel Voice’s burro was named Benny Burro, then!

I’ve always greatly enjoyed “The Bear and the Beav ers”, right down to Scott Bradley’s whistling chorus and the open “Went to the animal fair”.

Just noticed, and sorry, for my name typo.

Anyway, just enjoyed the Barney/Benny comic..! Makes me wish that they had teamed up in cartoons (both with voices).

While Bear and the Beavers promises great comic potential, it is marred by Ising’s Disney-esque approach to story and timing. The cartoon details its plot through the unnecessary courtesy of storybook pages. The cartoon could easily ensue without them, since there is primarily no dialogue. The cartoon’s climax is fairly weak: after Barney deprives the beavers of their firewood, they demolish Barney’s home. Sluggish timing is the culprit. If such an action played to an exaggerated degree, instead of the organized fashion, as seen here, the results would have paid off better. Scott Bradley’s musical score is nicely done, despite the cartoon’s shortcomings.

Watching this one again, the thing that always sticks out in my mind of Ising’s cartoons during this period was the excessive use of dissolves, especially within scene. It just seems distracting to me the way those are executed when a simple cut between shots would suffice. I don’t mind when it’s transitioning between the pages of the book used as a framing device, but it just comes off a tad overdone in my tastes.

The use of the book in telling the story was perhaps Ising’s way of wanting this to be like a fable with lesson one must learn at the end (in this case, a lesson Barney learns the hard way for his actions).