The witching hour draws nigh. But aside from the usual array of supernatural spooks and specters so common to the season, a more Earthbound variety of heavy is also a frequent inhabitant of the Halloween scene – the evil scientist. While such eggheads come in many varieties, and may as easily as not be engaged in monster making, mixing weird potions, building ray guns, etc. – this article will concentrate on one of said educated elite’s favorite pastimes -exchanging brains!

Brain transplants or personality swaps are usually the product of some form of sinister science in animated cinema – but occasionally occur from mere happenstance such as severe blows, amnesia, etc. We’ll try to cover a cross-section of all such causes herein, evil or no, and demonstrate the variety of unexpected consequences that can befall those who, with or against their will, attempt to play the part of someone else. However, for the time being, I will avoid “Jekyll and Hyde” parodies, as coverage of this overly-satirized literary work might well take up an article in its own right. Also, we’ll carve away hypnosis cartoons, which were also quite thick-on-the ground in animation’s golden era.

Brain transplants or personality swaps are usually the product of some form of sinister science in animated cinema – but occasionally occur from mere happenstance such as severe blows, amnesia, etc. We’ll try to cover a cross-section of all such causes herein, evil or no, and demonstrate the variety of unexpected consequences that can befall those who, with or against their will, attempt to play the part of someone else. However, for the time being, I will avoid “Jekyll and Hyde” parodies, as coverage of this overly-satirized literary work might well take up an article in its own right. Also, we’ll carve away hypnosis cartoons, which were also quite thick-on-the ground in animation’s golden era.

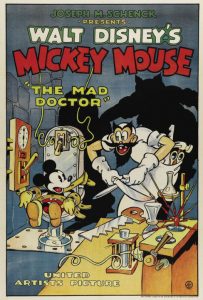

Perhaps the whole concept of scientific personality transfers begins with the unusually Gothic Disney classic, The Mad Doctor (Disney/UA, Mickey Mouse, 1/20/33 – David Hand, dir.). On a dark and mysterious night, in the middle of a thunderstorm, a shrouded figure lurks outside Mickey’s home – and drags away Pluto, to a sinister moated castle in the mountains, with sign on the front door reading “Dr. XXX”. The dognapper turns out to be the Doc himself, who manacles Pluto to a fluoroscope alongside an imprisoned rooster. The doctor announces in rhyme his great experiment – not a brain transfer, per se, but to graft the gizzard of the rooster onto the wishbone of the pup – and see if the crossed result will bark, or crow, or cackle! The doctor never really gets his experiment going, however, as Mickey follows his tracks to the castle – having encounters inside with bats, an array of live skeletons, a skeleton spider – and eventually the doctor himself, who binds Mickey by automatic means to an operating table, dusts off his midriff with an automated whisk broom, and lowers a buzzsaw from the ceiling to perform the dissection. Of course, it’s all a dream, and Pluto’s safe at home to slurp the waking Mickey.

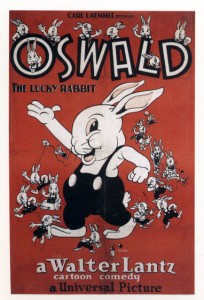

The Unpopular Mechanic (Lantz/Universal, Oswald the Rabbit, 11/6/36). Oswald, with his dog Elmer the Great Dane (character name playing on the title of Warner Bros. Joe E. Brown feature, Elmer the Great), finds his own scientific means of influencing the brains of his victims….that is, subjects…..as he tinkers with an invention from diagrams in the “Unpopular Mechanics” magazine, reading “Build a Radioscope Personality Changer – changes a wall flower into the life of the party.” Oswald installs the last radio tube into the portable device (about the size of a radio), adjusts a rotating “weather vane” pointer arrow on top of the machine to point at Elmer, and tunes a selector knob on the machine’s side, which lights up a screen on the front of the machine to read, “Crooner”. A zap of electrical energy projects from the arrow and hits Elmer – causing him to sing in his best impersonation of Bing Crosby – complete with “Boo Boo Boo Boo”s and whistling. “It works”, shouts Oswald, and he and Elmer run next door to show off his handiwork. In the next house, the Duck family – Mama, Papa, a tween-aged daughter playing piano, and five young quintuplets (Fee, Fi, Fo, Fum, and Fooey) are spending a quiet evening at home. Oswald bursts in with his creation – but the ducks see nothing to visually impress them, and try to ignore him. The quints are sent to bed, and Oswald and Elmer are left with the unappreciative parents and big sister. Sis is playing a routine rendition of “Chopsticks” on the piano. Oswald gets an idea and points his machine at her, tuning the selector to read “Jazz”. Sis is hit with a bolt, and promptly soups up her musical rendition with fancy riffs and jazz flourishes. Pop and Mom are appalled.

But Oswald is in no mood for criticism, and aims his arrow at them, setting the selector to “Tango”. Mom leaps up from the kitchen table with Spanish dance steps, using two dinner plates as castanets. Pop grabs the tablecloth and wraps it around himself like a Spanish cape, and Mom and Pop break into a full dance routine. But meanwhile, Fooey (the little black duck of the quints, with a reputation throughout the series for mischief) hears the music from the bedroom and peeps into the living room from behind a curtain. Seeing Oswald controlling the machine, and the parents dancing, he gets the idea what the gadget can do, and sees possibilities. He sneaks upon the machine when Ozzie isn’t looking, and changes the selector from “Tango” to “Apache”. His parents’ dance changes completely, and suddenly they are twirling and throwing each other across the room. Realizing something’s wrong, Oswald spots Fooey at the controls – but Fooey aims the arrow at Oswald, set to a new setting: “Swimmer”. Oswald dodges the electrical beams, and hides behind a console radio. Fooey figures out how to beat this tactic by bending the middle of the machine’s pointer arrow to form three sides of a square, then fires again. Now, the electric bolt does an up-and-over jump over the radio, hitting Oswald behind it. Oswald starts doing swimming strokes in midair, then dives under the living room carpet like the surface of the ocean, and up out the other side with a porpoise leap. Elmer growls, but Fooey hits him with a bolt with the selector reset for “Monkey” – causing Elmer to do aerial acrobatics from the chandelier. Everything is chaos, as Fooey rezaps everyone with their respective personality traits to keep them busy – then gets a new idea. He sets the machine to zap Maw, Paw, Oswald and Elmer together, with a setting reading “Quartette”. The four of them break into close harmony, in a musical number reminiscent of such then-known groups as The Revelers and The Comedian Harmonists. Just to spice things up, Fooey alternates with zaps while the machine is set for “Wrestler” – causing the quartet to “mix it up” as if in the ring between harmony lines.

But Oswald is in no mood for criticism, and aims his arrow at them, setting the selector to “Tango”. Mom leaps up from the kitchen table with Spanish dance steps, using two dinner plates as castanets. Pop grabs the tablecloth and wraps it around himself like a Spanish cape, and Mom and Pop break into a full dance routine. But meanwhile, Fooey (the little black duck of the quints, with a reputation throughout the series for mischief) hears the music from the bedroom and peeps into the living room from behind a curtain. Seeing Oswald controlling the machine, and the parents dancing, he gets the idea what the gadget can do, and sees possibilities. He sneaks upon the machine when Ozzie isn’t looking, and changes the selector from “Tango” to “Apache”. His parents’ dance changes completely, and suddenly they are twirling and throwing each other across the room. Realizing something’s wrong, Oswald spots Fooey at the controls – but Fooey aims the arrow at Oswald, set to a new setting: “Swimmer”. Oswald dodges the electrical beams, and hides behind a console radio. Fooey figures out how to beat this tactic by bending the middle of the machine’s pointer arrow to form three sides of a square, then fires again. Now, the electric bolt does an up-and-over jump over the radio, hitting Oswald behind it. Oswald starts doing swimming strokes in midair, then dives under the living room carpet like the surface of the ocean, and up out the other side with a porpoise leap. Elmer growls, but Fooey hits him with a bolt with the selector reset for “Monkey” – causing Elmer to do aerial acrobatics from the chandelier. Everything is chaos, as Fooey rezaps everyone with their respective personality traits to keep them busy – then gets a new idea. He sets the machine to zap Maw, Paw, Oswald and Elmer together, with a setting reading “Quartette”. The four of them break into close harmony, in a musical number reminiscent of such then-known groups as The Revelers and The Comedian Harmonists. Just to spice things up, Fooey alternates with zaps while the machine is set for “Wrestler” – causing the quartet to “mix it up” as if in the ring between harmony lines.

But Fooey misjudges his own height, and accidentally steps in the path of the machine’s ray while it’s still on the “Wrestler” setting – causing Fooey to begin picking himself up by the scruff of the neck to give himself judo flips. Back at the battle in the living room, Elmer emerges the winner of the tag-team match – and now turns his attentions to Fooey. Foeey, seeing blood in Elmer’s eye, makes a hasty exit, while Elmer grabs the machine and hurls it aside. He then approaches Sis and her piano, picking both of them up over his head and slamming them down against the floor. A cloud of dust obscures the scene, and when it clears, the house is destroyed from the force of the blow – and an exhausted Sis and the battered piano have rebounded into the branches of a tree. Below the tree sit a woozy Mom, Pop, and Oswald, with what’s left of Oswald’s machine. Mom and Pop come to, and glare at Ozzie. Ozzie is in total agreement with their mood, and gives the remains of his machine a good swift kick. The pointer arrow flies off the machine, into the air, and pierces the tree limb above where Sis is prone, poking her in the rear end. She immediately revives, takes her place on the piano stool again, and resumes her jazzy playing in the tree for a musical fade out.

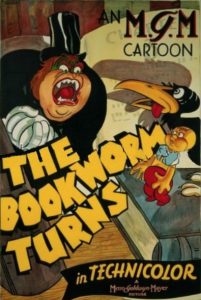

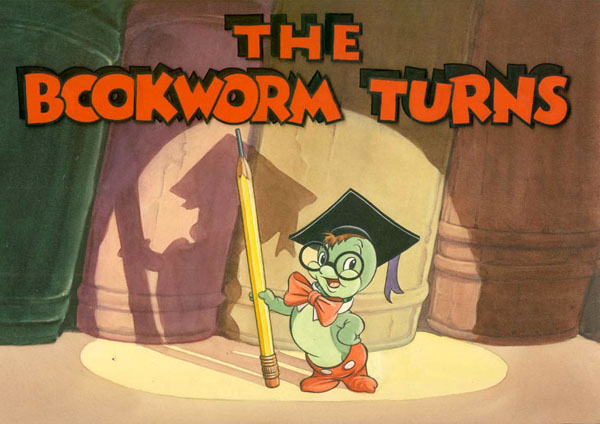

The Bookworm Turns (MGM, 7/20/40) is an elaborate sequel, anonymously directed by Friz Freleng in a short hiatus from the Warner Studios, following up upon Friz’s previous success, “The Bookworm” from 1938. Two characters are retained from the previous episode – the overly educated, puny, mortarboard-wearing worm, full of knowledge (from eating same in books every day), and Edgar Allen Poe’s Raven (from the book cover of the same name), a goon with a mind that is as evil as it is empty. (One character design change is made, however – the bookworm has developed actual arms and legs in this one, while in the original episode he slithered armless). The scene opens on the bookstore shelves, as the Raven looks out a window at gloomy, rainy skies. Announcing such days give him the “willies”, he claims to feel as if on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He spies a magazine ad, reading “Are You Dopey?”, plugging Dr. Quack’s liver pills. Concluding that this might be his problem, the Raven panics, and yells in the audience’s face, “Is there a doctor in the house?” A nearby book cover flashes its title in alternating neon signs: “Dr Jekyll – – – and Mr. Hyde”. Mr. Hyde (having the persona of a huge ape in a doctor suit) hears the call outside, mixes some potion – and after some hiccups and delayed results converts to Dr. Jekyll. For the remainder of the film he periodically transforms from one persona to another with each hiccup – causing the Raven to know he needs help – “I’m seein’ things!”

The Bookworm Turns (MGM, 7/20/40) is an elaborate sequel, anonymously directed by Friz Freleng in a short hiatus from the Warner Studios, following up upon Friz’s previous success, “The Bookworm” from 1938. Two characters are retained from the previous episode – the overly educated, puny, mortarboard-wearing worm, full of knowledge (from eating same in books every day), and Edgar Allen Poe’s Raven (from the book cover of the same name), a goon with a mind that is as evil as it is empty. (One character design change is made, however – the bookworm has developed actual arms and legs in this one, while in the original episode he slithered armless). The scene opens on the bookstore shelves, as the Raven looks out a window at gloomy, rainy skies. Announcing such days give him the “willies”, he claims to feel as if on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He spies a magazine ad, reading “Are You Dopey?”, plugging Dr. Quack’s liver pills. Concluding that this might be his problem, the Raven panics, and yells in the audience’s face, “Is there a doctor in the house?” A nearby book cover flashes its title in alternating neon signs: “Dr Jekyll – – – and Mr. Hyde”. Mr. Hyde (having the persona of a huge ape in a doctor suit) hears the call outside, mixes some potion – and after some hiccups and delayed results converts to Dr. Jekyll. For the remainder of the film he periodically transforms from one persona to another with each hiccup – causing the Raven to know he needs help – “I’m seein’ things!”

The doctor’s cure for dopeyness is a brain transfer, and he suggests the bookworm as a perfect specimen for the brain he needs. This sets up more of the chasing which had supplied most of the action in the preceding cartoon. As the bookworm leaps off a book page onto a globe, the Raven laughs that it’s a “small world”, and spins the globe violently, causing bookworm to run at top speed to keep up. “Where’s the fire?” taunts the Raven, flipping the worm into the air and catching him inside a skullhead bookend, in which he carries the worm back to Jekyll’s lab. Jekyll (or is it occasionally Hyde?) sets up two typical electric-chair type seats and brain transfer caps, amidst massive machinery and switches. “Gentlemen, you will suffer for the perpetration of this foul outrage”, warns the bookworm – only to have his cap fall over his face. Jekyll pulls the switch, and the voltage flows. “How do you feel?’, he asks the Raven after the process. In the longest words imaginable, the Raven refuses to lower himself to the Doctor’s level to even answer the question, punctuating his encyclopedia-raiding dialog with the concluding word, “Moron”. Meanwhile, all the bookworm can say is “I got the dopeyest feeling in my head.” Jekyll is satisfied with the success – but his “Hyde” kicks in, and he decides to have more fun with an enlarger device and the worm who is still tied to his chair.

With another pull of the switch, he transforms the worm into a monster ten times the Raven’s size. (Worm as his pants split: “I’m too big for my britches.”) The dopey giant decides to chase and taunt the Raven. The Raven meanwhile is reading up on the Einstein theory (illustrated with a picture of a baked pie, captioned “Pie are squared”), and comments, “Smart man, that Einstein. Knows what he’s talking about.” “Guess who dis is?” laughs the bookworm, looming above him. The Raven flees in terror while the worm pursues at a lumbering gait. Meanwhile back at the switch, another hiccup turns Hyde back to Jekyll – and he realizes maybe he’s pushed things too far. Struggling to pull another master switch, his machine sends out a huge electric bolt which magnetically sucks up the worm and Raven before one can do the other in. They are dropped into an elaborate maze of Technicolor receptacles, beakers and glass tubes, reminiscent of previous sequences of multicolor splendor used by Harman/Ising in the early Happy Harmonies, “Bottles” and “To Spring”. Somehow, worm is compressed back to normal size, and Raven restored to his old dopey self. Landing with a plop in front of a copy of “McGoofey’s First Reader”, the Raven concludes, “I guess there just ain’t no royal road to learnin’ – – indubitably!” In the last shot, Bookworm tries hopelessly to teach Raven out of the grade-school primer, but can’t even teach him how to spell “Cat”. Raven gets a typical curtain line, harkening back to comedians Moran and Mack’s “Two Black Crows” routine: “Aw, phoo! Who wants a brain anyway?”

The champion brain-switcher of the late 40’s and early 50’s is Bugs Bunny, who gets involved with such hare-brained schemes at least four times (excluding his additional encounters with hypnosis in The Hare Brained Hypnotist and with Jekyll-Hyde potions in Hare Remover and Hyde and Hare). Being a quick-change artist when it came to costuming, Bugs obviously wasn’t above a quick brain switch here or there if it meant a few laughs.

His first such outing was Hot Cross Bunny (Warner, 8/2148 – Robert McKimson, dir.) At the medical building of the “Paul Revere Foundation – hardly a man is now alive”, a doctor announces to a crowded surgical auditorium that he will attempt to transfer the brain of a chicken into a rabbit. In a hospital room, Bugs lounges in carefree fashion – having no idea why he gets three square meals a day, flowers, and even “gorgeous scenery” (pin up pictures of female rabbit models). The doctor wheels him in to the operating room in a wheelchair – which Bugs again accepts as luxury transportation. Spying the audience in the galleries, and told he is the central attraction, Bugs determines to ad-lib a show for them. First he impersonates wheelchair-bound actor Lionel Barrymore in his famous role as Dr. Gillespie. When this, a magic act, and a spirited tap dance fail to impress the onlookers, he gives them his “all out” job – a wild display of scat-singing gibberish in the style of Danny Kaye.

His first such outing was Hot Cross Bunny (Warner, 8/2148 – Robert McKimson, dir.) At the medical building of the “Paul Revere Foundation – hardly a man is now alive”, a doctor announces to a crowded surgical auditorium that he will attempt to transfer the brain of a chicken into a rabbit. In a hospital room, Bugs lounges in carefree fashion – having no idea why he gets three square meals a day, flowers, and even “gorgeous scenery” (pin up pictures of female rabbit models). The doctor wheels him in to the operating room in a wheelchair – which Bugs again accepts as luxury transportation. Spying the audience in the galleries, and told he is the central attraction, Bugs determines to ad-lib a show for them. First he impersonates wheelchair-bound actor Lionel Barrymore in his famous role as Dr. Gillespie. When this, a magic act, and a spirited tap dance fail to impress the onlookers, he gives them his “all out” job – a wild display of scat-singing gibberish in the style of Danny Kaye.

The doctor finally brings the shenanigans to an end by bopping Bugs on the head with a mallet. But even this doesn’t stop Bugs from transforming into a hot-dog hawker to try to earn a little spare change in the audience bleachers. Finally the doctor again announces his intentions, and Bugs insists, “Chicken? That’s out, doc!” Leading the doctor on a merry chase through the wards, Bugs rounds a laboratory table several times, mixing substances in a test tube on each pass, then cautions the doctor to stop. “This contains manganese, phosphorous, nitrate, lactic acid, and dextrose!” The Doctor laughs uproariously, telling him that’s the formula for “a chocolate malted.” Bugs tests this information by drinking it. “Yum Yum! I’m a better scientist than I thought.” The doctor finally subdues Bugs with laughing gas. Bugs is still in a laughing fit when brought back to the operating room and his brain-transfer hat is put on.

He looks at himself in a mirror, and states, “It don’t do a thing for me.” A major “convenient” plot device occurs here – so suddenly that you usually don’t catch it – as the Doctor prepares to pull the switch, a brain transfer hat appears on him as well as Bugs and the chicken. Why are there three hats – and what function does it serve for the doctor to wear one? Bugs hasn’t even moved, so who put it there? Anyway, McKimson gets away with it, and the chicken and Bugs are emersed in Technicolor electric bolts – but the attention of the electricity switches from Bugs’ position to the Doctor’s. As the lights come up, the Doctor starts crowing like a rooster. The chicken (in the Doctor’s voice), announces “In our next experiment, we will reverse the procedure – – I hope!” Bugs, standing to one side, holding a scissor and his cap which has been severed from the wiring, states, ”Looks like the Doc’s a victim of fowl play!”

See the film – and the animators draft – on Devon Baxter’s post here.

Water, Water, Every Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 4/19/52 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.), discussed briefly in previous post “The Invisible Article (Part 2)”, is motivated by an “Evil Scientist” (who boasts of such title in neon lights on his castle, that alternate with the word, “Boo!”), a parody of Vincent Price, who needs a “living brain” to power a monster robot. But the brain transfer process is never reached or revealed, as most of the footage is spent between Bugs and “Gossamer” – the red hairy monster with tennis shoes. The most memorable dialog between the scientist and Bugs is as follows: Scientist – “Now be a cooperative little bunny, and let me have your brain!” Bugs – “Sorry, Doc, but I need what little I’ve got.”

Water, Water, Every Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 4/19/52 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.), discussed briefly in previous post “The Invisible Article (Part 2)”, is motivated by an “Evil Scientist” (who boasts of such title in neon lights on his castle, that alternate with the word, “Boo!”), a parody of Vincent Price, who needs a “living brain” to power a monster robot. But the brain transfer process is never reached or revealed, as most of the footage is spent between Bugs and “Gossamer” – the red hairy monster with tennis shoes. The most memorable dialog between the scientist and Bugs is as follows: Scientist – “Now be a cooperative little bunny, and let me have your brain!” Bugs – “Sorry, Doc, but I need what little I’ve got.”

Hare Brush (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 5/7/55 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir,) is a sort of a high-science reworking of certain elements and sequences from Freleng’s earlier The Hare Brained Hypnotist (1942). At the “E. J. Fudd Building, a corporate board meeting is taking place, amidst visible concern from the board members. Their president make his appearance – Elmer, hopping into the room like a rabbit! He delivers the catch phrase, “What’s up, doc?”, then scurries away stating (without a trace of his usual “W” speech impediment), “Ooh, it’s rabbit season. The hunters will get me!” The board unanimously vote that immediate steps must be taken – and Elmer, dressed in an ill-fitting Bugs Bunny costume, is transferred to a psychiatric ward. Passing outside is the real Bugs – whom Elmer attracts to the barred window with a carrot. Signaling Bugs that he can have that and plenty more if he’ll open the window, Bugs replies, “Brother you’ve got yourself a preposition.” Once the bars are down, Elmer hops out and away, Bugs assuming he’s gone to look for more carrots – so Bugs keeps his bed warm for him. A psychiatrist assigned to the case enters, takes one look at the real Bugs, and comments “Worst case I’ve ever seen.” When Bugs proves an obstinate patient, the psychiatrist turns to more drastic measures, having Bugs swallow a pill. The pill has instant effects upon Bugs’ brain, causing him to adopt the slightest suggestion from the Doc. He is made to repeat the phrase, “I am Elmer J. Fudd, millionaire. I own a mansion and a yacht!” The pill is amazing, as with repeated repetition, Bugs even starts adopting Elmer’s “W” speech impediment!

Hare Brush (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 5/7/55 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir,) is a sort of a high-science reworking of certain elements and sequences from Freleng’s earlier The Hare Brained Hypnotist (1942). At the “E. J. Fudd Building, a corporate board meeting is taking place, amidst visible concern from the board members. Their president make his appearance – Elmer, hopping into the room like a rabbit! He delivers the catch phrase, “What’s up, doc?”, then scurries away stating (without a trace of his usual “W” speech impediment), “Ooh, it’s rabbit season. The hunters will get me!” The board unanimously vote that immediate steps must be taken – and Elmer, dressed in an ill-fitting Bugs Bunny costume, is transferred to a psychiatric ward. Passing outside is the real Bugs – whom Elmer attracts to the barred window with a carrot. Signaling Bugs that he can have that and plenty more if he’ll open the window, Bugs replies, “Brother you’ve got yourself a preposition.” Once the bars are down, Elmer hops out and away, Bugs assuming he’s gone to look for more carrots – so Bugs keeps his bed warm for him. A psychiatrist assigned to the case enters, takes one look at the real Bugs, and comments “Worst case I’ve ever seen.” When Bugs proves an obstinate patient, the psychiatrist turns to more drastic measures, having Bugs swallow a pill. The pill has instant effects upon Bugs’ brain, causing him to adopt the slightest suggestion from the Doc. He is made to repeat the phrase, “I am Elmer J. Fudd, millionaire. I own a mansion and a yacht!” The pill is amazing, as with repeated repetition, Bugs even starts adopting Elmer’s “W” speech impediment!

The remainder of the film, similar to its predecessor, engages in a prolonged hunting trip, with Bugs now dressed in Elmer’s hunting clothes, and Elmer burrowed in the ground and resorting to all of Bugs’ old bag of tricks. Just as Bugs finally gets Elmer at point-blank range, there is a tap on Bugs’s shoulder. A man in a well tailored business suit asks if he is Elmer J. Fudd. Bugs, still under the pill’s influence, repeats his well-learned phrase of being a millionaire with a mansion and a yacht. The man reveals he’s a “Special Agent. You owe three hundred thousand dollars in back taxes. I’m afraid you’ll have to come with me.” As Bugs is dragged off amidst protests of needing to hunt the “scwewy wabbit”, a smiling Elmer tips his hand to the audience – for the first time returning to his normal “W”-embedded dialog, and stating, “I may be a scwewy wabbit – But I’m not going to Alcatwaz!” He dances gaily into the woods to the step of the “Bunny Hop”, as we iris out.

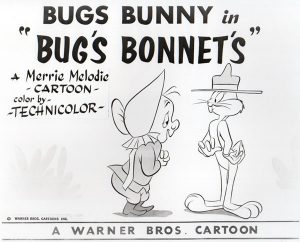

Bugs’ Bonnets (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 1/14/56 – Chuck Jones, dir.), presents a new low in low-tech means of personality transformation – built on the premise that “Clothes make the man” – or even the hat alone. An Acme Theatrical Hat Co. van driving along a woodland highway spills its entire load of hats, which blow and drift willy-nilly around the same forest where Elmer Fudd is engaged in a spirited rabbit hunt of our hero. Various chapeaus fall upon the brows of our sporting duo – transforming them instantly into a wide variety of characters. A Sergeant’s helmet falls on Bugs. He immediately starts calling out orders to Elmer to stand at attention and explain his actions. As Elmer explains he was out hunting with his gun, Bugs interrupts: “All right, dogface, how come every other private in this man’s army has a rifle, and you’ve got a gun??” Taking it away from him, he commands Elmer to march to the river bank – and straight in. Rising out of the water under more hats drifting in the stream, Elmer acquires a Douglas MacArthur general’s hat, and announces, “I have returned!” More hats result in more roles. Bugs becomes a game warden, while Elmer is switched to a Pilgrim hat and claims he’s shooting turkeys.

Bugs’ Bonnets (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 1/14/56 – Chuck Jones, dir.), presents a new low in low-tech means of personality transformation – built on the premise that “Clothes make the man” – or even the hat alone. An Acme Theatrical Hat Co. van driving along a woodland highway spills its entire load of hats, which blow and drift willy-nilly around the same forest where Elmer Fudd is engaged in a spirited rabbit hunt of our hero. Various chapeaus fall upon the brows of our sporting duo – transforming them instantly into a wide variety of characters. A Sergeant’s helmet falls on Bugs. He immediately starts calling out orders to Elmer to stand at attention and explain his actions. As Elmer explains he was out hunting with his gun, Bugs interrupts: “All right, dogface, how come every other private in this man’s army has a rifle, and you’ve got a gun??” Taking it away from him, he commands Elmer to march to the river bank – and straight in. Rising out of the water under more hats drifting in the stream, Elmer acquires a Douglas MacArthur general’s hat, and announces, “I have returned!” More hats result in more roles. Bugs becomes a game warden, while Elmer is switched to a Pilgrim hat and claims he’s shooting turkeys.

An Indian wig falls on Bugs, and he briefly goes on the warpath against the Pilgrim. Coming to a highway crossing, a bonnet falls on Elmer, converting him to the personality of a scared little old lady. Bugs meanwhile acquires a boy scout hat, and helps Elmer across the street. Their toppers blow off from a passing car, and the chase is on again. Bugs has a new hat that looks like Humphrey Bogart’s, and threatens gun-wielding Elmer for muscling in on his territory, claiming “I’ll rub ya’ out, see?” A policeman’s hat lands on Elmer, and he attempts to arrest the mobster. Bugs offers him a bribe. While Elmer is attempting to refuse, a judge’s wig lands on Bugs, while Elmer still has the money in his hand. Bugs delivers verdict: “You’re a family man. Monahan, so I’m only going to sentence you to 45 years – at hard labor.” But the sentence is interrupted, as a bridal veil falls on Elmer, prompting him to effeminately ask, “Will you marry me?” A formal top hat falls on Bugs, and he accepts the proposal. As Bugs carries his “bride” to a honeymoon cottage, he tells the audience, “You know, I think it always helps a picture to have a romantic ending.”

Next time, we encounter a pair of mind-mixer episodes from Tom and Jerry, more late theatricals, and the first ventures of television into scrambling brains more severely than the average effects of just watching the new medium.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Not sure if this example quite fits with your criteria, but there is also “The Worm Turns” (Disney, 1937) in which Mickey takes on the mad scientist role and concocts some quite literal liquid courage, which certainly upends the relationships between predator and prey; even the fire hydrant gets a chance to give its canine tormenter a taste of his own medicine.

I second the motion, that cartoon its great! It stills surprise me that the fire hydrant gag got past the Hays Code, but maybe because Disney had such a good reputation they let that one pass.

Interesting enough, I think Mickey Mouse, and Betty Boop on “Betty Boop M.D.” are the only cartoon characters I can think of that can play mad scientists (maybe Betty doesn’t make Jippo but she sure sells it) and still be considered “Good” in the context of the story. Mickey at least have the excuse of doing it for an altruistic purpose, even if it turns upside down the laws of nature, but Betty’s Jippo has side effects that are hard to ignore.

On the other hand, most of the mad doctors in these three articles except for Dr. XXX, Dr. Jekyll, and the evil scientist for “Water Water every Hare” are depicted more as whimsical that evil.

Nice selection of cartoons again, as always. I like “the bookworm turns“ along with the Oswald the Lucky rabbit cartoon you included. I like “the book worm turns“ also, because just about all the voices are done by Mel Blanc!

“Brain and brain! What is brain?” — Kara, “Spock’s Brain”

The old brain switcheroo has a long literary tradition going back to the 1882 novel Vice Versa by F. Astley. I’m especially fond of P. G. Wodehouse’s only foray into fantasy, his novel Laughing Gas (1936), in which an English Earl and a child actor switch places in Hollywood’s Golden Age. In the Edgar Rice Burroughs Barsoom novel “The Master Mind of Mars”, a Martian mad scientist has a lucrative enterprise surgically transplanting the brains of wealthy elderly Martians into the bodies of healthy young ones. Too bad Bob Clampett never had a chance to make his animated version of this story.

I suppose Bugs Bunny was able to appear in so many brain-switcher cartoons precisely because his personality was so well-defined. Face it, if Bosko or Buddy ever swapped brains with someone else, would anybody even notice?

Looking forward to following wherever your mind wanders next week.

I didn’t know the Bookworm sequel got directed by Freleng, that explains why is more funny that the first one. A minor nitpick I have is, I think the cartoon would flow better if the worm grew bigger almost immediately after he got his brain switched with the raven, the way its done feels random.

I think is one of the rare times in cartoons where the characters don’t swap voices after they exchange minds, even when the worm’s voice got rough after getting larger, his voice is still diferent for the raven’s.

A key difference I noted between the older cartoons doing this plot vs the more recent ones is that the victims remain oblivious of the change for the most part, or even for the entire duration of the thing, even if any observers tell them directly. In the newer shows the characters affected by it freak out almost instantly. In paper it sounds funnier to make the characters do wild takes at the sight of each other, but in practice I think the alternative works better, the joke being that the characters are too dense to note such an obvious thing.

Fleischer sure beat Disney at showing a dog swapping heads with a chicken, even if that Bimbo cartoon never explained why that happened.

Thinking about it, exchanging heads seems more visually interesting for an animation standpoint that switching brains. In most of these personality swapping cartoons, if you turn the volume off you wouldn’t know what the heck is going on, specially if it is because of magic instead of “science”, unless you really pay attention to some subtle changes in body language between the two chararcters, of if the mind its swapped with a chicken. Some shows in the 90s try to rectify this by making the characters getting each other eye shapes to cue you of the change, but that kind of defeats the point of the characters looking like each other.