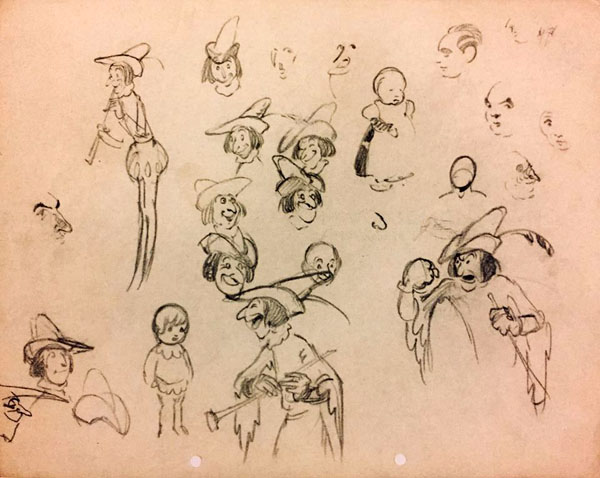

Albert Hurter sketches for “The Pied Piper”

The tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin originates from a German folk tale that dates to the 13th century, with written sources originating towards the 16th century. English poet Robert Browning (1812-1889) adapted the story into a poem, “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” which was published in 1842. As the story follows, the town of Hamelin is stricken with a rat infestation, which leads to a public outcry for a solution to dispose of the vermin. Aware of their problem, a piper approaches the Mayor and promises to rid their town of rats, in return for payment. After the piper lures the rats away with his instrument, the Mayor reneges on the promised fee and pays the Piper only a paltry sum. Swearing vengeance, the Pied Piper entices the children of Hamelin away from their parents, and they follow him to a mountainside, where the authority figures cannot enter.

The tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin originates from a German folk tale that dates to the 13th century, with written sources originating towards the 16th century. English poet Robert Browning (1812-1889) adapted the story into a poem, “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” which was published in 1842. As the story follows, the town of Hamelin is stricken with a rat infestation, which leads to a public outcry for a solution to dispose of the vermin. Aware of their problem, a piper approaches the Mayor and promises to rid their town of rats, in return for payment. After the piper lures the rats away with his instrument, the Mayor reneges on the promised fee and pays the Piper only a paltry sum. Swearing vengeance, the Pied Piper entices the children of Hamelin away from their parents, and they follow him to a mountainside, where the authority figures cannot enter.

The story outline for Disney’s adaptation of the folk tale circulated around the studio in April 1933, shortly before the release of Three Little Pigs. Naturally, Disney alleviated the dreadful aspects from its German origins and Robert Browning’s poem. For instance, when the Piper leads the rats away from Hamelin, he advances them into the Weser River, where they drown. In Disney’s retelling, the instrument the Pied Piper’s instrument materializes an enormous round of Swiss cheese, which disappears once every rodent dives in. In Robert Browning’s poem, the mountainside envelops all the children of Hamelin, except for one boy with an injured leg who is left behind. However, the other children are never reclaimed from the mountain. To protect Depression-era audiences from a grim ending, Disney’s version is brighter. All the children, including the boy on crutches, enter into a “Joyland” — a carefree land of sweets, toys and activities.

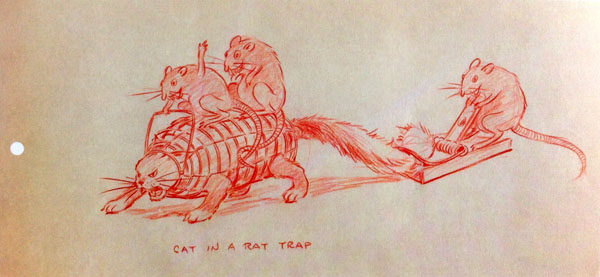

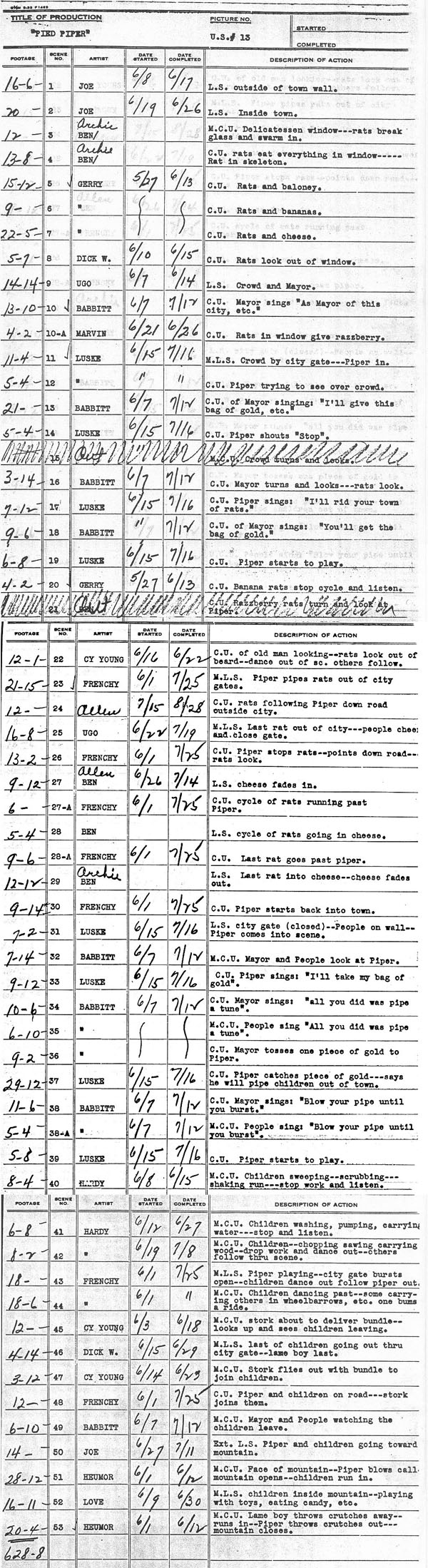

Albert Hurter served at the inspirational sketch artist for the film, and Ferdinand Horvath drew background layouts, which started on May 12th, a month after the film’s story outline was distributed. By May 27th, director Wilfred Jackson assigned the animators their scenes. Rather than give animators different sequences, he cast the film by character, much like Three Little Pigs. Ham Luske and Art Babbitt animated key scenes of the Piper and the Mayor, while Clyde “Gerry” Geronimi animates much of the various scenes of the rats devouring food.

The Pied Piper was the first attempt by the studio to animate central characters that are human beings at their core. In the film’s operetta fashion—with its dialogue sung or rhymed—the animation from Luske and Babbitt certainly has a theatrical essence in the scenes where the Piper and Mayor interact. Though the character acting is not strong in this film, one of Babbitt’s scenes of the Mayor, his derisive look of corruption as he tosses the Piper only one coin for payment, is effective.

Ben Sharpsteen’s crew of junior animators—which included Joe D’Igalo, Marvin Woodward, Ugo D’Orsi, Cy Young, Paul Allen, Hardie Gramatky and Ed Love—animate much of the crowd shots of the rats, as well as the Hamelin townsfolk and children. (Interestingly, in the draft, scene 24—with the rats following the Piper outside of Hamelin—is credited to junior animator Paul Allen, while scene 26, and subsequent shots the Piper appears, are credited to “Frenchy” de Tremaudan; since they are a continuation of the same shot, it could be safe to assume that scene 24 is handled by “Frenchy” de Tremaudan, as well.) The film’s layout work ended by early June 1933, and animation was finished by August 28th.

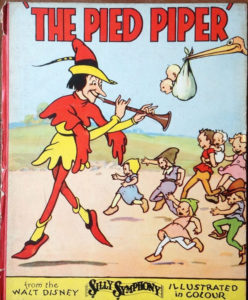

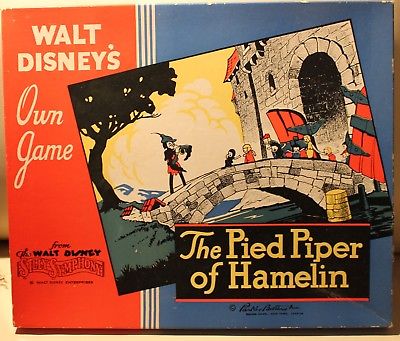

Based on the popularity and success of Mickey Mouse and Three Little Pigs during the height of the Great Depression, subsequent Silly Symphonies cartoons generated various merchandising tie-ins. After the release of The Pied Piper in September 1933, Parker Brothers released a board game based on the film, and London publisher Bodley Head issued a storybook adaptation, copyrighted 1934. In November 1933, almost a year before the studio took on their most ambitious project with a feature-length animated film, Ted Sears voiced the studio’s dissatisfaction with the results of the film when he wrote to animator Izzie Klein in New York: “We’ve come to the conclusion that our best screen values are in cute animal characters. We haven’t advanced far enough to handle humans properly and make them perform well enough to compete with real actors.”

Here’s the breakdown video, along with an original 1933 production draft of The Pied Piper. Enjoy!

Thanks for your continued support of these posts. I’ll be back on March 28th.

(Thanks to Mark Kausler, J.B. Kaufman and Michael Barrier for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Ham Luske’s introductory moment for the Piper — where he walks in spinning his pipe to indicate his own self-confidence — is also effective in quickly establishing character. But overall, this may be one of the shorts that caused Disney to later threaten not to hire Shamus Culhane, based on the problems Walt told him the studio had trying to break former Fleischer Studio animators of their bad habits (going by Sears’ letter to Klein).

Of course, Disney couldn’t let the rats to be killed in their version. His main star was a mouse!

At least it’s a bit humane, though you do wonder where do the rats go after that, another dimension, or some kind of limbo?

THEY VANISH INTO OBLIVION

“Disney’s version is brighter. All the children, including the boy on crutches, enter into a “Joyland” — a carefree land of sweets, toys and activities.”

Where, presumably, they will be turned into donkeys and sold into manual labour. 😉