Due to the recent workload from my position at a warehouse (which ships electronics and accessories) and joining the restoration team for Steve Stanchfield’s Thunderbean Animation (cleaning up three Flip the Frog titles), I will be less frequent in my posts for Cartoon Research. On another note, I have hardly touched my Radio Round-Up book project, and am mostly in the process of gathering notes. This is far from the end of Baxter’s Breakdowns, but I will most likely contribute at least every other month. I would like to thank all of the readers for their patience. For now, appropriate for the month of August, I present to you an animator breakdown featuring an early undersea Silly Symphony…

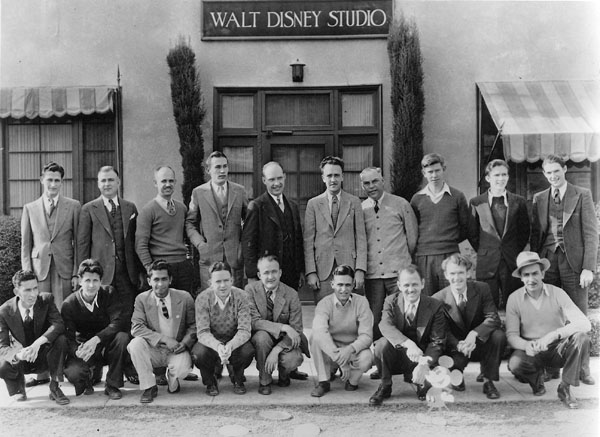

The Disney studio staff, before Ub Iwerks and Carl Stalling left.

With the departure of top animator Ub Iwerks and musical composer Carl Stalling in January 1930, Walt Disney’s staff mostly consisted of experienced animators from various New York studios and homegrown artists—namely, Les Clark, Wilfred Jackson and Johnny Cannon—hired during the production of the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit shorts during the late 1920s. Iwerks was persuaded by film executive Pat Powers to head his own animation studio, along with Stalling. Powers offered Disney the use of his Cinephone sound system for Steamboat Willie (1928), which led to a distribution deal to release Mickey Mouse and the Silly Symphonies series under Powers’ Celebrity Productions. Powers’ supposed withholding of Walt and his brother Roy’s share of the rental fees from the films—and his offer to Iwerks that led him away from the studio—severed their partnership the following February. A short time later, Disney signed a contract with Columbia Pictures to distribute their films.

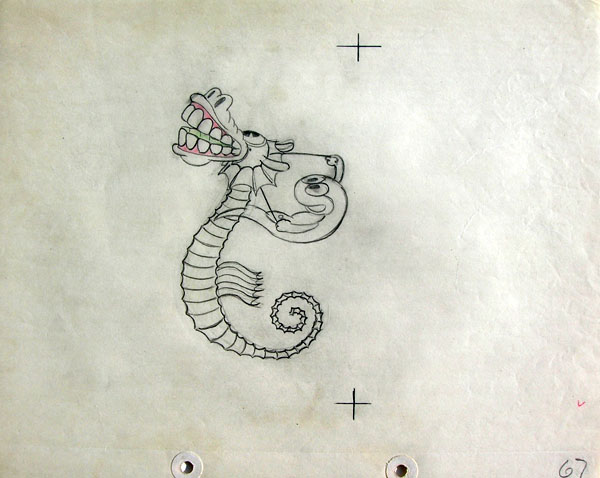

Without Iwerks as the key artist that shaped the studio’s films, Disney scrutinized the subtle details in the work of his staff, now grown to 30 artists, to achieve a significant and precise effect. Frolicking Fish adheres to the fashion of early sound cartoons which Disney and Iwerks molded, as the various underwater creatures dance and cavort to a syncopated accompaniment of the musical beat. One of the methods Disney suggested for improving the animation in his cartoons was to vary the spacing in between the drawings for characters to slow out of a pose before shifting to the next, rather than the rigid nature of held positions between each drawing.

Without Iwerks as the key artist that shaped the studio’s films, Disney scrutinized the subtle details in the work of his staff, now grown to 30 artists, to achieve a significant and precise effect. Frolicking Fish adheres to the fashion of early sound cartoons which Disney and Iwerks molded, as the various underwater creatures dance and cavort to a syncopated accompaniment of the musical beat. One of the methods Disney suggested for improving the animation in his cartoons was to vary the spacing in between the drawings for characters to slow out of a pose before shifting to the next, rather than the rigid nature of held positions between each drawing.

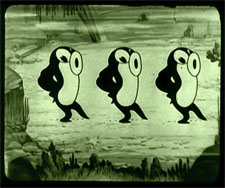

After animation for Frolicking Fish commenced by April 1930, a significant breakthrough occurred. Scenes 6 and 7, as animated by Norm Ferguson, a trio of fish performs a soft-shoe dance in front of an audience. This sequence became notable for its use of “moving holds,” or overlapping animation, as the fish achieve a smooth, continuous motion throughout their dance number without relying heavily on held poses. Ferguson’s animation impressed his fellow artists, and Disney had his artists study the sequence as an example of his aspirations toward enhancing the quality of his films. By comparison, the following scene of the fish orchestra and the swordfish twanging his proboscis like a Jew’s harp (animated by Dave Hand, as confirmed in the exposure sheets but not listed in the notes displayed here) move in the rigid and mechanical practice that the studio sought to avoid.

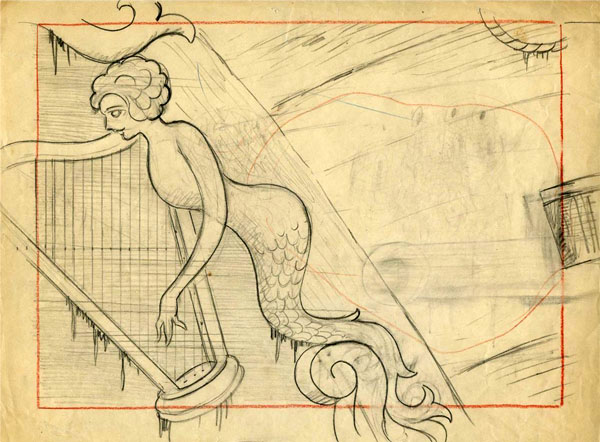

Early in the series, Disney and his artists strived to shape the Silly Symphonies into a cohesive narrative structure, although the shorts maintained their approach similar to vaudeville, where different characters are given their own sequences to dance and play. The intruding octopus in the cartoon suggests a sense of danger in the form of an antagonist set to terrify and devour the central characters—or an entire population, as in this film. Unlike the whooping crane that appears only at the end of Springtime (1929) to chase after frogs, or the lion pursuing natives in Cannibal Capers (1930) in the second half of the film, the threat of the octopus in Frolicking Fish is established early, and its presence is known throughout the rest of the film.

Early in the series, Disney and his artists strived to shape the Silly Symphonies into a cohesive narrative structure, although the shorts maintained their approach similar to vaudeville, where different characters are given their own sequences to dance and play. The intruding octopus in the cartoon suggests a sense of danger in the form of an antagonist set to terrify and devour the central characters—or an entire population, as in this film. Unlike the whooping crane that appears only at the end of Springtime (1929) to chase after frogs, or the lion pursuing natives in Cannibal Capers (1930) in the second half of the film, the threat of the octopus in Frolicking Fish is established early, and its presence is known throughout the rest of the film.

After the octopus emerges from the sea chest (animated by Wilfred Jackson), various song-and-dance acts follow, perhaps from the mollusk’s perspective to determine its nefarious conquest. As several little fish float on top of bubbles, the octopus rises below to pop them one by one, giggling with fiendish glee, as handled by Les Clark. One fish becomes trapped in a bubble and the octopus captures him. It performs its own dance, toying with its victim by tossing and catching him back-and-forth (animated by Ben Sharpsteen) before the fish is in his clutches. After the octopus puts the fish in his mouth and smiles to the camera, it reveals a gap in his teeth, which provides his captor an escape. Though subsequent Silly Symphonies used various settings and a large amount of small characters to defeat a large menace, only this fish vanquishes the octopus by dropping an anchor on his head, as bubbles and black ink billow from his body. Merle Gilson, the animator responsible for this last shot of the film, was one of the few artists that left the Disney studio to join Iwerks as one of his assistants.

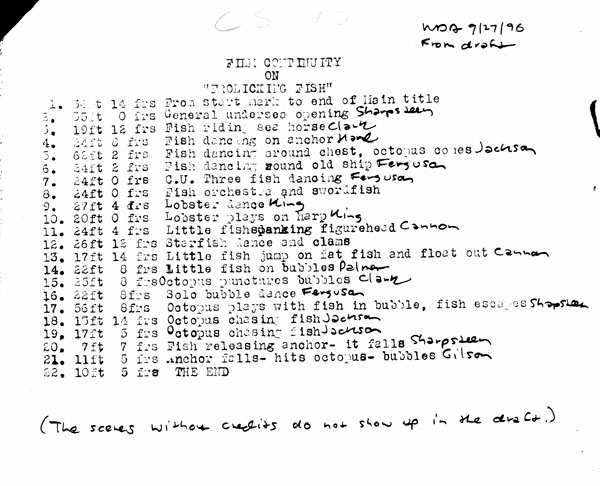

The premiere of Frolicking Fish occurred on July 19th, 1930 in Washington D.C. It opened in New York that September. Original prints of this film were printed on green stock to produce an effect appropriate for the setting, which is re-instated on the video below. Instead of an original handwritten production draft, presented here is the cutting continuity with Michael Barrier’s notes denoting the animators’ assignments based on the original documentation. Scene 12, of the group of starfish dancing and clams clacking like castanets, is unconfirmed without any evidence from surviving documentation, including exposure sheets.

Enjoy!

Next week, there will be an animator breakdown I have been anxious to write since the beginning…

(Thanks to Mark Kausler, J.B. Kaufman and Michael Barrier for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Many similar gags and poses showed up years later in the Beautiful Briny sequence in Bedknobs and Broomsticks.

I wonder how the cartoons are represented in that now out-of-print vinyl box of SILLY SYMPHONIES scores; how many cartoons were they able to fit on one vinyl side, as opposed to a CD?

I like the early SILLY SYMPHONIES, along with the Ub Iwerks cartoons of the earliest period, like the FLIP cartoons. Glad to hear that you’re helping restore the FLIP cartoons. Whenever that ends up in my mailbox, it will certainly be welcome. Thanks for these, and I look forward to the next one to find out which title you’ve wanted to map out in detail. I personally wish that mroe MGM Harman/Ising era cartoons would be dissected. There is so much detail that I recall frm those…and still more that I’d want a memory jog.

The end title is the villian’s afterlife?

That’s a lot of fun! I like the green film stock; it gives a great effect. I’d never heard of that.

Great to see this in green and with original titles too. Thanks a lot.