Today’s animator breakdown gathers insight into Bugs in Love and Bucky Bug, a little guy with a big history!

In conjunction with the Mickey Mouse comic strips by Floyd Gottfredson, syndicated by King Features, Disney’s comic department dedicated a full Sunday color page when they launched a featured Silly Symphony strip on January 10, 1932. Story man Earl Duvall wrote, penciled and inked the earliest installments of the Sunday strip, with narration blocks and dialogue balloons delivered entirely in rhyme.

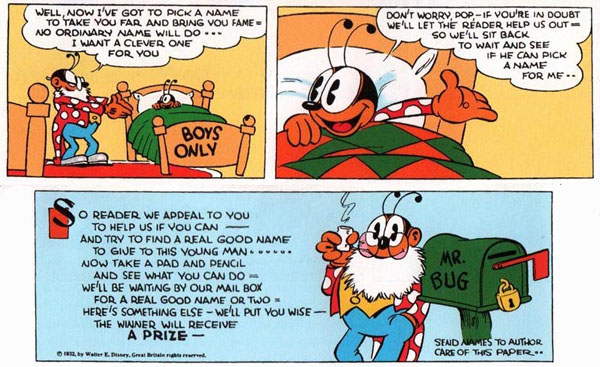

The Silly Symphonies comics featured an unnamed boy bug in their town of Junkville, which played on the tiny scale of the insect communities as they dwelled and frolicked among discarded clutter left by humans, no doubt reminiscent of Gus Dirks’ Bugville and Harrison Cady’s Beetleburgh illustrations from the early 20th century. Shortly after the strip’s debut, a contest was held for readers to submit proposed names to their newspapers—the resulting winner was Bucky (sometimes spelled “Buckey”).

The Silly Symphonies comics featured an unnamed boy bug in their town of Junkville, which played on the tiny scale of the insect communities as they dwelled and frolicked among discarded clutter left by humans, no doubt reminiscent of Gus Dirks’ Bugville and Harrison Cady’s Beetleburgh illustrations from the early 20th century. Shortly after the strip’s debut, a contest was held for readers to submit proposed names to their newspapers—the resulting winner was Bucky (sometimes spelled “Buckey”).

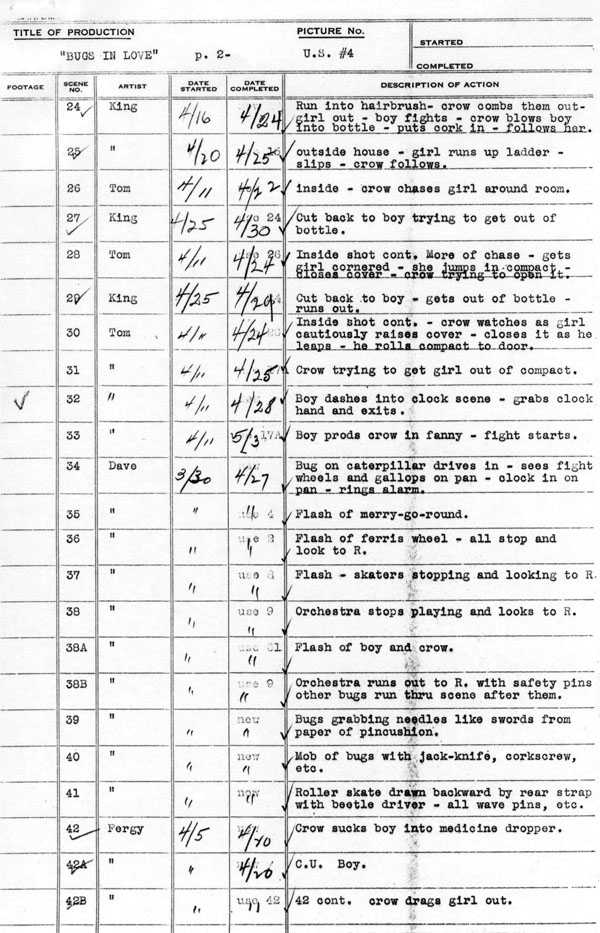

During the strip’s early months, Disney’s animation department started production on Bugs in Love, under the working title “Bug Symphony.” In the film, Bucky Bug and his girlfriend June Bug are plumper in appearance, as in the early January 1932 strips. The large crow set to devour June Bug is named Squire Cawker in the comics— villainous in a Victorian approach, he is portrayed as a dastardly predator in the film and serves as the merciless landlord of Junkville in the comic strip. No records of story meeting notes survive from the film, though judging from the original production draft, animation began around March 30, 1932, a few weeks after Bucky was officially named in the comics.

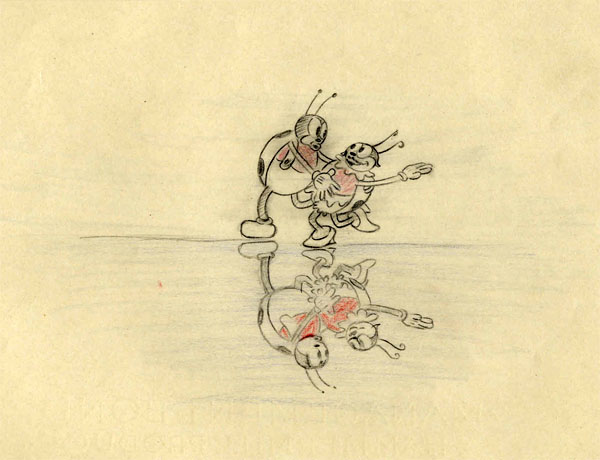

Bugs in Love is primarily cast by sequence, with key animators Les Clark, Jack King, Tom Palmer, Norm Ferguson and “Frenchy” de Tremaudan, who handles two brief sequences in the film. Clark handles the courtship between Bucky and June Bug, as they skate along a mirror and express their sentiments through handwritten exchanges. Jack King animates the crow stalking the bug couple and his pursuit of June Bug outside of her house, while Tom Palmer’s animation follows when the crow chases June Bug inside, as he pushes away any piece of furniture in his path. Palmer also continues the action that follows outside, as the fight between the bugs and the crow ensues, when Bucky jabs him with the sharp hand of a clock. Besides animating June Bug applying make-up inside her house, he also handles the ending scene of the bug couple’s reunion as they share a kiss, privacy from the army of bugs notwithstanding.

Recent research has indicated that a crew of junior animators worked under the supervision of Dave Hand, though the animation draft offers no clues as to different scene assignments—only crediting the scenes to Hand. The opening scenes of the bugs in Junkville, using throwaway objects as their own carnival fairgrounds, and their preparation for the climactic battle against the crow are only indicated in surviving exposure sheets from the film. These animators included Joe D’Igalo, Charles Hutchinson, Ed Love, Frank Tipper, Hardie Gramatky, Ham Luske, Bill Roberts, and Fred Moore. Moore’s animation of the bug riding on a caterpillar gallops to sound the alarm to attack—using a discarded alarm clock—in scene 34, displays an early insight into his talents in appeal and weight before his rise to prominence, which led to the studio’s house style throughout the 1930s.

Though exposure sheets have revealed some clues about the junior animators under Dave Hand and Ben Sharpsteen—thanks to the invaluable work of J.B. Kaufman—the survival status of the exposure sheet is spotty. For instance, the small scene of the bugs swinging on garter straps gives no credit to any of Hand’s junior animators in the draft, but no exposure sheet survives to indicate their identities. Sadly, none survive from scene 42 onward, which begins with Norm Ferguson’s credit in the draft. During this period, Ferguson also worked with a crew of junior animators—in this case, Eddie Donnelly, a former animator for Paul Terry’s Fables Studios and Van Beuren in New York during the 1920s and early 1930s.

Based on his experience, Donnelly is credited in a small number of scenes, but it is unclear if he animated these himself or under Ferguson’s supervision. Also, it is uncertain if Ferguson supervised the work of Donnelly and Charles Hutchinson (for one brief scene) in the exact fashion as Hand or Sharpsteen. It could be speculated that his animation is seen in the film with the help of assistant animators to handle the extensive sequence.

By the time animation on Bugs in Love finished around May 3, 1932, Earl Duvall handed over the penciling and inking chores of the “Bucky Bug” Sunday strip to Al Taliaferro, while Duvall still served as a writer. In 1933, he left the Disney studio; the Silly Symphony strip’s writing duties were given to Ted Osborne. Duvall moved to Harman-Ising as a story man and became a director after producer Leon Schlesinger opened his own independent studio after Harman and Ising split their association from Schlesinger. One of his last directorial credits, the risqué Honeymoon Hotel (1934), featured a similar bug couple and insect environment, and is noteworthy as the first Warner Bros. cartoon produced in color. However, the success of the film inspired a drunken altercation towards Schlesinger over a pay raise, which led to his termination.

Bucky Bug’s appearances on the Silly Symphonies Sunday strip ended with his marriage to June Bug on March 4, 1934. In 1942, Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories reprinted the original Sunday strips, which its readers enjoyed, so Western Publishing decided to produce original stories featuring Bucky Bug. Al Taliaferro drew the first exclusive comic book story in issue #39 (December 1943), while other artists such as Vive Risto, Carl Buettner, Don Gunn, George Waiss and Ralph Heimdahl drew the featured “Bucky Bug” stories, which lasted until 1950. Bucky Bug developed a strong following among overseas readers, which led to new stories in European countries. Dutch comic magazines continue to produce new Bucky Bug to this present day, though foreign countries have not translated the stories in verse as the original comics were patterned.

If you’re interested in reading the original Silly Symphonies strips with Bucky Bug spanning from 1932-34, IDW has published Silly Symphonies Volume 1: The Complete Disney Classics, available now!

(Thanks to Mark Kausler, J.B. Kaufman and Dave Gerstein for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

And If you want to see ol’ Bucky getting “down n’ dirty”, seek out those classic Air Pirates Funnies ..

Love those SILLY SYMPHONIES, perhaps the two volumes of classic Disney cartoons I cherish most, although the later “HONEYMOON HOTEL” is really a charming cartoon.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but it appears that “Bugs in Love” was the final black and white Silly Symphony.

You are correct!

I’ve always wondered what happened to Earl Duvall after Warners.

The most I have been able to find is he landed at Iwerks briefly, followed by a brief return to Disney and then retirement. So for about 30 years his whereabouts and activities are a mystery.

https://www.lambiek.net/artists/d/duvall_earl.htm

It’s interesting to see two animators working at Disney on this film in 1932: Charles Hutchenson and Frank Tipper. They had both worked for Ted Eshbaugh on his cartoons ‘The Snowman’ and ‘Wizard of Oz’. I wondered if they landed at Disney right after the Oz project was first cancelled/ delayed in 1932, ironically likely because of Disney deal with Technicolor.

Note to crow: next time, instead of sucking the Boy bug into an eyedropper, why not just eat him?

I didn’t know Taliaferro drew a few WDC&S Bucky stories (the one mentioned plus in #60) and updated his Wikipedia entry accordingly.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al_Taliaferro