Here’s a real treat…a breakdown of Chuck Jones’ directorial debut!

I mentioned a few weeks ago that, as far as I knew, there were no drafts from Jones’ Warner Bros. cartoons I have since then been assured that these documents, indeed, exist.

Chuck Jones is a highly significant figure in animation, but his esteem couldn’t have been sustained without the company of his colleagues Friz Freleng, Bob McKimson, Bob Clampett, Tex Avery and Frank Tashlin. Jones attended the Chouinard School of Art after he quit high school. During his first year, he worked part-time as a janitor in order to pay for his fine arts studies. After enrolling in Chouinard, around 1930, Jones had an unsuccessful stint in commercial art. Classmate Fred Kopietz recommended him to Ub Iwerks’ studio, where he became a cel washer. He rose through the ranks as an inker, painter and in-betweener before Iwerks terminated him.

In March 1933, he started at Leon Schlesinger’s studio as an assistant animator for Paul Fennell. Jones soon became a full-fledged animator, with 1934’s The Miller’s Daughter as his first on-screen credit. Tex Avery arrived at the studio in 1935 and recruited Jones to the original “Termite Terrace” unit with Bob Clampett and newcomers Virgil Ross and Sid Sutherland, creating irreverent B&W Looney Tunes beyond the norm.

After Avery’s promotion to direct the color Merrie Melodies, Jones and Clampett went over to the Iwerks studio to supervise two cartoons – Porky and Gabby and Porky’s Super Service – in order for them to be recognizable as Schlesinger product. Jones was Clampett’s head animator and character layout artist on his first few cartoons. His excellent character designs and drawing style cemented the look of those cartoons. Chuck’s approach to drawing and animation were finely handled, such as his scenes of the objectionable Mr. Viper in Avery’s Milk and Money.

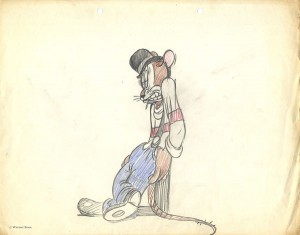

Jones stepped into the director’s chair in the spring of 1938, after Frank Tashlin’s departure over an argument with studio assistant Henry Binder. Animation for The Night Watchman was underway by mid-April, as indicated on the draft, with Bob McKimson and Ken Harris as Jones’ two lead artists. Chuck’s early cartoons embraced the Disney philosophy, with realistic movement and layered colors that suggested depth and contour. These early efforts have slower pacing and are gentler than the studio’s trademark brassy, eccentric output.

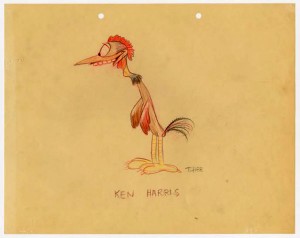

McKimson’s scenes closely follow Chuck’s layouts and brim with detail, often using difficult angles on the head and body of the characters. He handles most of the scenes with the tough leader rat, and uses subtle, unobtrusive gestures, such as the leader rat drumming his fingers against the chair waiting for his steak in scene 18. He also employs some great streak lines in sc. 34 when little Tommy Cat rushes over to the mouse hole, plumber’s helper in hand.It’s interesting to see how Ken Harris’ early style, before it became more recognizable in Jones’ cartoons of the ‘40s and ‘50s. Harris has a propensity for smears in this cartoon, such as the drummer rat in scene 18 and Tommy’s cathartic punching sequence in scene 32. He trained under McKimson, and his use of clever touches in these scenes show the influence of the studio’s most gifted draftsman. The drummer rat swallowing a chocolate while performing, and Tommy stepping over a defeated rat as he moves on to the next one, are cleverly handled. Harris also animates the rats performing the swing rendition of “In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree,” performed by the Sportsmen Quartet.

Phil Monroe’s animation in Night Watchman shows more elasticity than McKimson’s or Harris’. When he started at Schlesinger’s in the summer of 1934, Monroe was McKimson’s in-betweener and was later his assistant. He handles the introduction scenes of Tommy Cat (in one of Margaret Hill-Tarlton’s first vocal roles for cartoons) that establishes his clumsiness before guarding the kitchen. Scene 17, where Tommy attempts to be assertive towards a rat cook only to be brusquely shooed away, is wonderfully acted.

It’s surprising to see Ace Gamer, typically an effects animator, credited for character animation here His rats are drawn in a simplistic fashion, and seem more like rodents from the Freleng unit. Gamer’s last few intercuts of Tommy trying to silence them during the musical sequence have exaggerated drawings similar to a Clampett Looney Tune.Ben Washam and Rod Scribner started animating around 1938; hence they are only credited with one scene. There are slight earmarks of Scribner’s future drawing style as the cowardly rats back away from Tommy. Jones removed Scribner from his unit, and the animator moved to the Hardaway/Dalton unit. Based on speculation, Jones believed Scribner’s animation didn’t fit his vision of attempting a Disney style. In later years, as Monroe claimed in an interview, Jones grew to respect his animation.

There is a perplexing mystery on The Night Watchman breakdown. There is an uncredited artist, misspelled “Kieth,” on scene 12. Could it be Keith Darling? Darling’s credits as an animator for Warners begin in the mid-50s. This might have been a test scene, but more is not known. The hypothesis of Darling’s identification comes from in-betweener Lee Halpern’s appearance in the 1939 Termite Terrace gag reel. His credits as an animator first appear in the early ‘60s. Did these animators work for decades before their first screen credits? There are rumors that the story for this cartoon might have been finalized by late ’37, before Jones was slated to direct. Since the rats appear like a Freleng cartoon in some sequences, one wonders if he was the intended director prior to his time at MGM?

Jones was ambitious in his first cartoon in other aspects. Note the extensive use of double exposure, used for the illumination of Tommy’s flashlight, the singing rat trio against the spotlight and the ghosting effect on the “better self” sequence. The characters tend to flicker in these scenes, because the shots were reversed and re-exposed for the transparency by hand-cranking them. When the cameraman would turn back the individual frames, they would have to guess the exposure – a tricky feat before the advent of electric-drive animation cameras.

Hope you all enjoy this one! Expect many more Jones cartoons to follow! (No requests, please.)

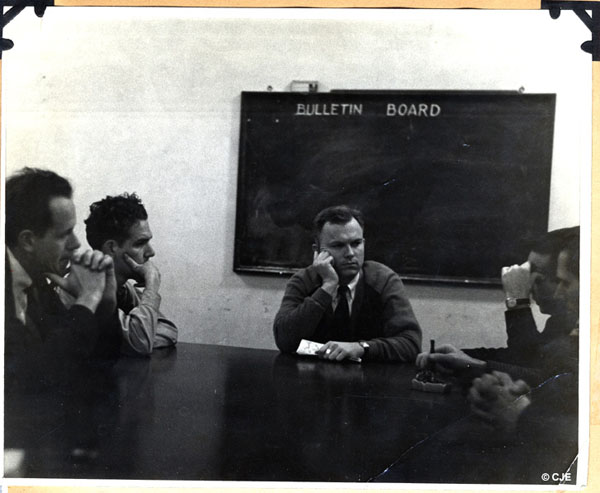

Chuck Jones, Unit A

Images courtesy of the Chuck Jones Center for Creativity. Looney Tunes characters, names, and all related indicia are TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. 2015.

(Thanks to Michael Barrier, Keith Scott, Frank Young – and each and every week, Jerry Beck – for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

One of the rare cat and mouse cartoons where we’re rooting for the cat to win (though since they’re rats, it may not count).

Devon – are the colors in this video really supposed to be that bright and garish? (Me and my brother had a term for this – “bozing”, as in “boze it up”, meaning turn up the saturation knob on the TV. Derived from Bozo the clown of course.) I somehow doubt it ever looked like this on a theater screen.

Keith Darling is in a studio photo in Martha Sigall’s book. It looks to date from the late ’30s. His signature is also on the list of Schlesinger people who decided to pop by the Disney picket line in 1941 (one of Jones’ books).

When he got married in 1945, his occupation on the marriage certificate is listed as “Cartoonist, Warner Bros. studio.”

If you look at Frank Tashln’s :”Have You Got Any Castles?” from earlier in 1938, there’s a gag book title in the background at the 5:42 mark on “Guilds — Their Formation and Management”, which is credited to “Darling in association with Ted Pierce”. It’s not an absolute smoking gun, but it does indicate there was a “Darling” active in the Tashlin unit that year, which Jones would inherit. So ‘Keith’ being Keith Darling wouldn’t be a surprise (nor would the idea that Keith and Ted were among those at the time leading the effort to unionize the Schlesinger studio at the time, based on the background painting).

Since even Avery was doing cute/marauding mice cartoons in the 1937-38 period, it’s possible this was cartoon that might have been started by Friz’s unit and then shelved. But it definitely doesn’t feel like one Chuck inherited from Tashlin, as would be the case moving into the 1940s, when most new directors’ initial cartoons tended to be ones they inherited at least in part from their predecessor.

Congratulations on a top-notch job!

As usual, Greg Duffell was right to an extent, from what he told me. Rod Scribner was originally from Frank Tashlin’s unit. It appears that he landed in Jones’ unit when it first started, and not long after he moved out. Who would’ve thought he had animated anything for Jones?

As for Washam’s scene, I recall reading in an interview with him by Joe Adamson, that Washam was an assistant on this short. Washam wouldn’t receive his first animation credit until four years later on “Conrad the Sailor”. It’s possible that Benny was given that small piece of animation as a leftover scene.

It’s a delight to see many of the scenes incidate when it started and finished, and it’s easier to tell how much footage the individual animators cranked out. McKimson apears to be a speed demon here, a 34 feet scene indicated in the final shot only took three days (May 29-June 1). Harris’ 48 feet shot in sc. 32 is two weeks worth of work…and not to mention the complexity of the scene, and the number of different levels he had to animate for the individual mice. It’s amazing how they could crank out that much footage. It appears to take Monroe about a week to handle a 15-20 foot scene, as shown in sc. 5, which took an entire week.

Is this print on one of the recent DVDs? I don’t recall seeing the non-“Blue Ribbon” version before.

Indeed, it is — from the fourth GOLDEN COLLECTION set.

WHAT BREAKDOWN ANMATION SHOULD HE DO NEXT

Looking at that photo of the Jones unit reminded me of the old Ed Selzer quote “What in the Hell does all of this laughter have to do with the making of animated cartoons?”. Yep, that photo really shows the Hellzapoppin’ atmosphere in Chuck’s shop. Of course it could have been taken B.S. (Before Selzer).

Fine work, Devon…thanks to people like yourself, Yowp and Thad we’re entering a new form of cartoon history, with period documentation and YouTube capability existing side by side, along with accurate historical information. What a refreshing change from the last few years of mindless fanboy guesswork and misinformation. By the way, Art, that photo predates the Selzer period.

Thanks Keith. They look so grim, like a group of government officials discussing the ramifications of the Manhattan Project.

Are you SURE that the Sportsmen provided the singing for the hot vocal trio heard in this cartoon? I am not.

First of all, the Sportsmen were a quartet, and we’re dealing with a trio here.

Thee had been a vogue for hotcha vocal trios ever since Paul Whiteman unleashed the Rhythm Boys on an unsuspecting America in the late 1920’s. AT this time, the Top Hatters were quite busy. (They appeared as “The Freshmen” on Ray Noble’s 1935 Victor records, such as “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails”, as well as on a few Decca records of their own.

This vogue extended to the other side of the color line, as well. Jimmie Luncedford featured a trio of musicians form within his ranks who sang hotcha numbers on several Decca recordings. (e. g. “Since My Best Gal Turned Me Down”).

Even Duke Ellington featured a trio of band-members on “I’ve Got To Be A Rug Cutter” (q. v.)

I think of the Sportsmen as being a little later than this period. I know that they did MacGregor radio transcriptions around 1942 as an a capella male quarter. By the middle 1940’s, they were regulars on Jack Benny’s radio show.

By the way, the song heard over the opening scenes is “I Can’t Face The Music (Without Singing The Blues)”.

And you never know what lurks in the background of a Warner Bros. cartoon. There’s one of those midnite-in-a-magazine-stand cartoons where a character is running in front of a row of pulp magazines–one of which advertises a thrilling tale: “Revenge of the In-Betweeners”!

It was indeed members of the Sportsmen who sang for this cartoon…they were known as the Sportsmen, The Merry Men and other names in the late 1930s, according to music department records at USC for MGM musicals. Members Thurl Ravenscroft and Bill Days both told me they did “all the WB cartoons”…as early as 1936, when they were known at first as the Metropolitans and had a different bass singer, they did cartoons and background work in shorts and films. All the records I found for WB cartoons showed that they were contracted as the Paul Taylor group…Taylor was the choirmaster on Crosby’s Kraft Music Hall, and he is listed at as being present at all the sessions with the Sportsmen, who were listed as Ravenscroft, Days , Smith and Rarig. Taylor occasionally supplied a large chorus for WB cartoons as in CRACKED ICE or CINDERELLA MEETS FELLA. The Sportsmen you mention from the mid-1940s Jack Benny Program lineup had some different personnel by then (bass singer Ravenscroft had left for war service and was replaced by Gurney Bell), but they still did cartoons like BOOK REVUE. This cartoon does indeed sound like a trio…but Ravenscroft and Jones both told me in telephone calls that Thurl was there for THE NIGHT WATCHMAN, indicating he may have sung a part that went unused in the final cartoon…Thurl said to me, “I was with Chuck on his first cartoon and he called me all those years later for the GRINCH.” By the way, Devon, it’s Margaret Hill-TALBOT…Marjorie Tarlton was a different voice actress.

The voice of Tommy Cat was done by Margaret Hill-Talbot.