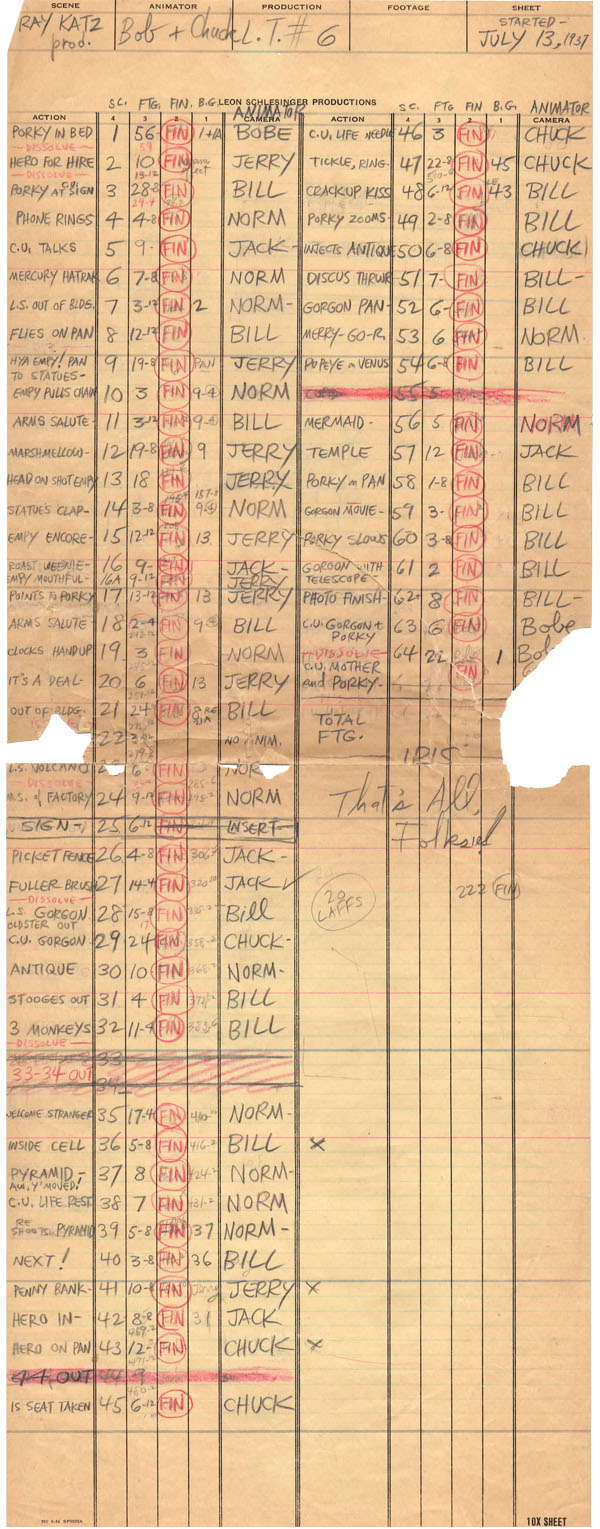

Having finished the animation for Porky’s Badtime Story at the end of April 1937, Bob Clampett’s directorial unit migrated from Ub Iwerks’s Beverly Hills studio to establish their business on the first floor of the building that—back in 1933—had once housed Leon Schlesinger’s animation workplace earlier. Schlesinger’s brother-in-law/production manager Ray Katz supervised Clampett’s unit as a separate creative house, situated apart from the rest of Leon’s studio. Starting with his second Looney Tune, Get Rich Quick Porky, Clampett performed double duty as both writer and director of his cartoons, while Chuck Jones continued his function as Bob’s leading animator and character layout man. In the production draft for Clampett’s third cartoon, Rover’s Rival, the director’s slot in the top margins lists “Bob + Chuck,” providing conclusive evidence that Clampett and Jones actually directed as a team. On July 13, 1937, Clampett’s unit engaged in their fourth Looney Tune under the working title “Greek Story.” The “Bob + Chuck” credit also appears in its production draft, confirming another of Clampett’s early Looney Tunes on which the two acted as a directorial team.

Having finished the animation for Porky’s Badtime Story at the end of April 1937, Bob Clampett’s directorial unit migrated from Ub Iwerks’s Beverly Hills studio to establish their business on the first floor of the building that—back in 1933—had once housed Leon Schlesinger’s animation workplace earlier. Schlesinger’s brother-in-law/production manager Ray Katz supervised Clampett’s unit as a separate creative house, situated apart from the rest of Leon’s studio. Starting with his second Looney Tune, Get Rich Quick Porky, Clampett performed double duty as both writer and director of his cartoons, while Chuck Jones continued his function as Bob’s leading animator and character layout man. In the production draft for Clampett’s third cartoon, Rover’s Rival, the director’s slot in the top margins lists “Bob + Chuck,” providing conclusive evidence that Clampett and Jones actually directed as a team. On July 13, 1937, Clampett’s unit engaged in their fourth Looney Tune under the working title “Greek Story.” The “Bob + Chuck” credit also appears in its production draft, confirming another of Clampett’s early Looney Tunes on which the two acted as a directorial team.

Greek dialect comedy was in vogue during the thirties, predominantly transmitted by two fictional figures. One was the “Greek Ambassador of Good Will,” a role performed by actor George Givot. Another was the character of Nick Parkyakarkus (e. g. “park your carcass”), a Grecian chef portrayed by Harry Einstein, AKA Harry Parke, on Eddie Cantor’s radio program (Einstein, it should be noted, would become the father of two well-known humorists and comedians of the last 50 years, Albert Brooks and Bob (“Super Dave”) Einstein).

George Givot and Parkyakarkus

As early as 1936, the East Coast artists at Max Fleischer and Van Beuren were already inspired by the Greek humor vogue, reflecting it in different ways. Van Beuren’s It’s A Greek Life, written and directed by Dan Gordon, takes place in ancient Greece, presenting mythological beings that speak in fractured English. In Fleischer’s two-reel Technicolor special Popeye the Sailor Meets Sinbad the Sailor, the inspiration is shown by Boola, the two-headed giant, who spouts the same regional vernacular as George Givot’s Greek Ambassador. As for Schlesinger, Clampett’s first directorial job—an animated segment for the Joe E. Brown feature When’s Your Birthday — featured a satiric battle between zodiac signs residing in the heavens. Their actions are commented upon, via voiceover, by an astrology expert modeled after the Greek Ambassador.

For further context, here is an excerpt from MGM’s 1934 two-color Technicolor short, Roast Beef and Movies, featuring George Givot’s Greek Ambassador, with Jerry “Curly” Howard and Bobby Callahan as his co-stars.

As Clampett and his team set to work on their fourth Looney Tune, Warner Bros. was midway through post-production on their upcoming musical feature Varsity Show. Previewed in August 1937 and formally released in September, Varsity Show featured a selection of Warners-owned songs by Johnny Mercer and Richard A. Whiting that would figure heavily in Porky’s Hero Agency. Carl Stalling (misspelled “Stallings” on the title card) incorporated four Varsity Show tunes into the cartoon: “Have You Got Any Castles, Baby?,” “Old King Cole,” “Love is on the Air Tonight,” and “You’ve Got Something There.” Stalling enjoyed using excerpts from Varsity Show’s music, adding Mercer and Whiting’s hit tunes to the scores of subsequent Schlesinger cartoons during the late 1930s.

The opening title card of Hero Agency puts Porky into the pantheon of legendary Greek figures by displaying his molded statuette at the center of the frame. In an introductory scene animated by Bobe Cannon, Porky sits in bed reading a bound volume of Greek myths. Porky’s mother (voice actress unknown) tells her son to go to sleep for the night; the impressionable young pig chatters to his “Ma” about what he’s been reading, as a small child would. Since his debut as a schoolboy in I Haven’t Got a Hat (Freleng, 1935), Porky’s shift from a small child to an adult and back again could take place wherever the plot necessitated—Wholly Smoke (Tashlin, 1938), Old Glory (Jones, 1939), and The Film Fan (Clampett, 1939) provide later examples of Porky assuming the role of a schoolboy. The valiant music heard underneath the main titles and the opening scene is “March Dignitare: Grand March,” composed by Edward John Walt (1877-1951) and published in 1930 as part of the Sam Fox School Orchestra Series.

Describing his book to his mother, Porky mentions the Gorgon—who turned Grecians into statues—and the hero that vanquished her, saving the populace. The three Gorgon sisters of early Greek literature had hair made of living coiling snakes and, through their evil gaze, turned onlookers into stone. Porky’s summary of the tale to his mother refers to the slaying of Medusa, the third (and only mortal) Gorgon, by Perseus. Before Porky drifts off to sleep, the envious young pig wishes to be a “great, great, great Greek hero” as the viewer watches the cover of his mythology book, showing a temple exterior, undulating and swaying close to the camera.

Porky’s yearning dialogue alludes to the Golden Fleece and slaying dragons, implying that he has also read the tale of Jason and the Argonauts retrieving the Golden Fleece—a legendary ram’s golden wool—from the Colchian Dragon. As for Porky’s reference to “rescuing fair damsels,” stories of men rescuing women abound in Greek literature (Perseus and Andromeda, and Hermes saving Persephone from Hades, to cite a few examples.)

Porky’s yearning dialogue alludes to the Golden Fleece and slaying dragons, implying that he has also read the tale of Jason and the Argonauts retrieving the Golden Fleece—a legendary ram’s golden wool—from the Colchian Dragon. As for Porky’s reference to “rescuing fair damsels,” stories of men rescuing women abound in Greek literature (Perseus and Andromeda, and Hermes saving Persephone from Hades, to cite a few examples.)

Porky dreams he is “Porkykarkus,” the proprietor of a hero-for-hire agency—his professional name is lifted from radio’s Nick Parkyakarkus. Among the specials listed on Porky’s rate card include a $50 fee for each dragon slain (rounding up to $1,050 in 2023 US currency); an ingenious usage of Mercer and Whiting’s “Have You Got Any Castles, Baby” underscores our young hero publicizing his services—the song mentions slain dragons in one verse, “Have you got any dragons that you want to have killed, baby?” At the bottom of the rate card, emblazoned in large letters, is the phrase, “Is Your Daughter Safe?” referring to the lurid exploitation film of the same name, released a decade before Hero Agency.

After reading his sign aloud for us, Porky answers a phone call from the Emperor, who orders “one hero to go.” Clampett cleverly infuses an ironic social commentary when Porky uses a statue of Mercury doubling as a hat rack and telephone receiver, grabbing his messenger cap and Talaria, the winged sandals. In mythology, Mercury was the Roman messenger of the gods, whereas Hermes was the Greek messenger. During his flight to the Emperor’s temple, Porky struggles to balance on his winged sandals, delineating his adventurous image as an imperfect hero.

Porkykarkus lands during a “fireside chat” addressed by Emperor Jones, his name extracted from the eponymous 1920 Eugene O’Neill play and its 1933 film adaptation. At the time of this film, U. S. President Franklin Roosevelt kept the American public abreast of various timely topics and issues through a series of informal speeches on national radio, typically called fireside chats. When Emperor Jones speaks to his royal council, he opens his statement with “My friends…” mimicking Roosevelt’s upper-class articulation, before adding “Grecians and customers” in a reading mirroring Nick Parkyakarkus’s Greek accent. When the emperor continues with “This is Emperor Jones speaking,” his tonality seems to allude to the soft-spoken speech of Alexander Woolcott, a prolific writer and essayist known for his radio program The Town Crier.

Porkykarkus lands during a “fireside chat” addressed by Emperor Jones, his name extracted from the eponymous 1920 Eugene O’Neill play and its 1933 film adaptation. At the time of this film, U. S. President Franklin Roosevelt kept the American public abreast of various timely topics and issues through a series of informal speeches on national radio, typically called fireside chats. When Emperor Jones speaks to his royal council, he opens his statement with “My friends…” mimicking Roosevelt’s upper-class articulation, before adding “Grecians and customers” in a reading mirroring Nick Parkyakarkus’s Greek accent. When the emperor continues with “This is Emperor Jones speaking,” his tonality seems to allude to the soft-spoken speech of Alexander Woolcott, a prolific writer and essayist known for his radio program The Town Crier.

In an extended sequence of political satire set to Mercer and Whiting’s “Old King Cole,” Emperor Jones orates to his council, which we see is comprised entirely of statues. The Emperor uses a marionette rig to make his “sheeps” salute and applaud his spiel as he explains the current crisis: an increasing number of his subjects, like the council, have been turned to stone by “that good-for- nothing Gorgon.” (Emperor Jones also uses one statue to roast a marshmallow and a hot dog while delivering his speech!)

Beyond referencing Parkykarkus in Porky’s name of “Porkykarkus,” Clampett adapts the radio character’s voice for Emperor Jones, borrowing Parkyakarkus’s Greek accent and mangled grammar familiar to thirties audiences. Starting on March 2, 1937 — four months before production began on Hero Agency — Harry Einstein as Parkyakarkas became a character exclusive to Al Jolson’s radio show after appearing the previous season on Eddie Cantor’s Texaco Town. Einstein’s persona, credited only as “Parkyakarkus,” concurrently appeared in films released the same year by RKO: New Faces of 1937 and The Life of the Party.

Here is an audio excerpt of Al Jolson and Parkyakarus on Jolson’s radio program The Lifebuoy Show from April 6, 1937, a month after Parky joined the cast exclusively.

When the Emperor mentions that the Gorgon carries a “Bring-Em-Back-Alive Life Restorer” needle that will turn each petrified citizen back to normal, the term “bring ‘em back alive” suggests the 1930 bestseller that launched the career of famed author, filmmaker, and animal collector Frank Buck. Jerry Hathcock, responsible for the majority of footage in Emperor Jones’s speech, was new to Schlesinger’s studio at the time, starting his term in Clampett’s new unit. Hathcock had come over from Ub Iwerks’s studio, where he started as early as 1934 on the Willie Whopper series. Later in his career, Hathcock would work for Walt Disney, MGM, UPA, and Hanna-Barbera.

Tasked with retrieving the life-restoring needle from the Gorgon, Porky flies into the chamber of a volcano, where the Gorgon has conveniently stationed her statue factory. Porky disguises himself as a messenger boy delivering a telegram, but a sentry’s hand swipes the envelope and brusquely shuts the door; a statue of a door-to-door Fuller Brush salesman, familiar to many households in the 1930s, is used as a doorstop, implying that his intrusive peddling may have caused his fate. The Gorgon operates like a professional photographer’s studio where her victims are forced—and at times, willing—to pose in front of her. Acting as her own camera, she sets her head on a tripod and puts a photographic lens over her evil eye before snapping a “picture,” petrifying her subject into rock.

Tasked with retrieving the life-restoring needle from the Gorgon, Porky flies into the chamber of a volcano, where the Gorgon has conveniently stationed her statue factory. Porky disguises himself as a messenger boy delivering a telegram, but a sentry’s hand swipes the envelope and brusquely shuts the door; a statue of a door-to-door Fuller Brush salesman, familiar to many households in the 1930s, is used as a doorstop, implying that his intrusive peddling may have caused his fate. The Gorgon operates like a professional photographer’s studio where her victims are forced—and at times, willing—to pose in front of her. Acting as her own camera, she sets her head on a tripod and puts a photographic lens over her evil eye before snapping a “picture,” petrifying her subject into rock.

Clampett and Jones portray the Gorgon as a cocky but somewhat ditzy witch-like character: a comic villain instead of the deadly or fiendish menaces that tended to be more common in animated cartoons. The Gorgon’s voice characterization was borrowed from another radio personality: Bill Comstock’s character Tizzie Lish, frequently heard on the popular comedy show Al Pearce and His Gang. Voiced by story man Tedd Pierce, Tizzie Lish-type characters also appeared in Schlesinger’s The Woods Are Full of Cuckoos (Tashlin, 1937) and Jungle Jitters (Freleng, 1938), released shortly after Hero Agency. Alien as Emperor Jones’ and the Gorgon’s voice characterizations may seem to viewers today, the cultural references would have resonated naturally with Depression-era audiences. On the other hand, the characters’ idiosyncratic quirks are such that they remain successfully amusing eccentrics, independent of their radio origins.

Since 1937 radio broadcasts of Al Pearce and His Gang are extremely scarce, here is an early appearance of Tizzie Lish from the first episode of The Mirth Parade, a short 15-minute syndicated series from 1933, hosted by Don Wilson (pre-Jack Benny).

Norm McCabe had joined the Clampett unit as an animator with the earlier Get Rich Quick Porky. He received marginal footage in Get Rich, but Clampett assigned him substantial character business in Rover’s Rival.

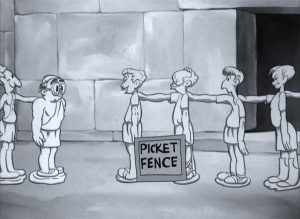

Moving on to Hero Agency, McCabe handled the sequence of Porky knocking on another door to bring the Gorgon out, uttering the catchphrase of the salesman character Elmer Blurt, also heard on Al Peace and His Gang (“I hope-I hope-I hope…”). Porky is whisked inside by a hulking guard (also voiced by Tedd Pierce) and brought over to stand in line with the rest of the Gorgon’s victims. McCabe also animates the following sequence, in which the Gorgon creates a human pyramid—rather than have the acrobatic figures “pop” from flesh to stone in a single drawing, McCabe drew them sequentially morphing into stone. The sequence also demonstrates the life restorer’s purpose, when the Gorgon injects the pyramid and transforms it back into human form for a picture retake. Terrified, Porky pictures himself as a stone piggybank and backs away, bumping into a statue of “Dick A. Powello,” which tips over and shatters. The actor Dick Powell starred and sang in many Warner Bros. musicals in the 1930s, including Varsity Show; adding the “A.” makes his name a pun on the Greek god Apollo.

In a scene animated by John Carey, Porky emerges with the upper half of the “Dick A. Powello” statue covering his torso, while a sheet hides everything below his waist. The Gorgon and her snake headband are both astonished by the seemingly handsome character—viewers may notice that the snake winks at the camera when the Gorgon speaks directly to the audience. Chuck Jones picks up the following sequence starting with the sheet falling from Porky’s waist, revealing his small plump body, but the revelation doesn’t stop the smitten Gorgon from sitting next to “Mr. A. Powello” on a couch. Porky attempts to grasp the life restorer needle but winds up touching the Gorgon’s torso, which she reacts to in sheer ecstasy and draws the statue close, smothering him with kisses. (The exact significance of the Gorgon’s line, “Can you taste the difference?” is an enigma to this author, though the phrase was used in concurrent advertising for Beech-Nut gum and Old Drum whiskey.) Catering to her romantic fantasies, the Gorgon takes a ring from her hand, reaches it around the statue, and places it back onto her finger again, pretending “A. Powello” has put it there—and feigning surprise that the statue has proposed marriage so quickly. Their intimate moment literally crumbles when the Gorgon embraces her new beau; his identity revealed, a shocked Porkykarkus swipes the life restorer and scurries away to inject the formula into each subject he passes.

In a scene animated by John Carey, Porky emerges with the upper half of the “Dick A. Powello” statue covering his torso, while a sheet hides everything below his waist. The Gorgon and her snake headband are both astonished by the seemingly handsome character—viewers may notice that the snake winks at the camera when the Gorgon speaks directly to the audience. Chuck Jones picks up the following sequence starting with the sheet falling from Porky’s waist, revealing his small plump body, but the revelation doesn’t stop the smitten Gorgon from sitting next to “Mr. A. Powello” on a couch. Porky attempts to grasp the life restorer needle but winds up touching the Gorgon’s torso, which she reacts to in sheer ecstasy and draws the statue close, smothering him with kisses. (The exact significance of the Gorgon’s line, “Can you taste the difference?” is an enigma to this author, though the phrase was used in concurrent advertising for Beech-Nut gum and Old Drum whiskey.) Catering to her romantic fantasies, the Gorgon takes a ring from her hand, reaches it around the statue, and places it back onto her finger again, pretending “A. Powello” has put it there—and feigning surprise that the statue has proposed marriage so quickly. Their intimate moment literally crumbles when the Gorgon embraces her new beau; his identity revealed, a shocked Porkykarkus swipes the life restorer and scurries away to inject the formula into each subject he passes.

During the chase, Porky restores life to the “antique” model seen earlier in the film, along with the Discobolus and the Venus De Milo, both unique ancient Greek sculptures. In repairing the armless Venus before restoring her to life, Porky grants her a pair of forearms resembling Popeye the Sailor’s, with a moment of Fleischer’s Popeye theme song heard on the soundtrack! Our hero rescues figures anachronistic to the period: after a dose of the life restorer, the Native American subject in James Earl Fraser’s 1894 sculpture The End of the Trail rides his horse like a carousel mount. Porky also administers shots to two Greek temples, one large and another small— the small temple is labeled “Shirley,” a reference to child star Shirley Temple, who was still active in films during 1937. The scenes intercut between Porky urgently running and the Gorgon adjusting to the medium of motion pictures, using her head as a hand-cranked film camera. As we cut from the pursuing Gorgon to a Porky close-up and back, her lens changes from a normal lens to a protruding telephoto lens. Porky freezes in place, and the Gorgon pins him to the ground, trying to force the young pig to open his eyes. The action dissolves to Porky’s mother awakening her son; Porky opens his eyes but, still believing his Grecian dreams are real, lies motionless like a statue for two seconds before giving a reassuring hug to his Ma. Bobe Cannon animated the closing scene of this shift between dream and reality, effectively bookending the cartoon.

During the chase, Porky restores life to the “antique” model seen earlier in the film, along with the Discobolus and the Venus De Milo, both unique ancient Greek sculptures. In repairing the armless Venus before restoring her to life, Porky grants her a pair of forearms resembling Popeye the Sailor’s, with a moment of Fleischer’s Popeye theme song heard on the soundtrack! Our hero rescues figures anachronistic to the period: after a dose of the life restorer, the Native American subject in James Earl Fraser’s 1894 sculpture The End of the Trail rides his horse like a carousel mount. Porky also administers shots to two Greek temples, one large and another small— the small temple is labeled “Shirley,” a reference to child star Shirley Temple, who was still active in films during 1937. The scenes intercut between Porky urgently running and the Gorgon adjusting to the medium of motion pictures, using her head as a hand-cranked film camera. As we cut from the pursuing Gorgon to a Porky close-up and back, her lens changes from a normal lens to a protruding telephoto lens. Porky freezes in place, and the Gorgon pins him to the ground, trying to force the young pig to open his eyes. The action dissolves to Porky’s mother awakening her son; Porky opens his eyes but, still believing his Grecian dreams are real, lies motionless like a statue for two seconds before giving a reassuring hug to his Ma. Bobe Cannon animated the closing scene of this shift between dream and reality, effectively bookending the cartoon.

Four months after early production began, Porky’s Hero Agency debuted on the week of November 13, 1937, at the Strand Theater on Broadway, with its announced release date on December 4. The Film Daily’s press review from December 3 referenced the Gorgon as “Medusa,” and Porky’s “Dick A. Powello” disguise as simply Adonis, functioning dually as the Greek god of beauty and desire and as current slang for an attractive male. (In fairness, this author believes that “Pork-seus” would have been a better alternate name for Porky in the film.)

Thanks to Jerry Beck, Ruth Clampett, Keith Scott, E. O. Costello, and Daniel Goldmark for the production materials and additional information. Special acknowledgment to David Gerstein for editing the text.

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Well, how d’you like that? I like it very much! Not only for the detailed background of the cartoon’s production, but also for the film and radio materials that give it context. “Roast Beef and Movies” never approaches the level of slapstick mastery that Curly Howard would commit as a Stooge, but it’s still a very funny film thanks to George Givot, and the musical numbers are terrific. That Parkyakarkus is a regular Buzz Berkopoulos!

The only other animated Gorgon I can think of offhand was in Hanna-Barbera’s “The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”. Far from being a comic villain, that Gorgon was so fearsome that it was only shown in shadow.

“Pork-seus”…. That’s clever, but maybe just a little too clever for a Bob Clampett cartoo-oon.

Fascinating that Clampett and Jones were actual, honest-to-goodness co-directors on a couple of cartoons. That really blows my mind. Congratulations on a fantastic article!

“That’s clever, but maybe just a little too clever for a Bob Clampett cartoo-oon.”

I first saw this cartoon only a couple of years ago, and I thought – perhaps unfairly to Clampett – that most of the Greek mythology references came from Jones.

Wasn’t the picket fence made up of caricatures of the animators?

Yes – Chuck Jones, Bob Clampett, Ernest Gee, Lu Guarnier, Jack Carey and Bobe Cannon.

When I was a kid this one always gave off a kind of horror movie vibe (Hammer eventually produced “The Gorgon”). Porky wearing the top half of a human statue was funny and creepy at the same time, what with the lack of pants and all. And even then I was thinking, if the statues were all recoverable humans, did Porky kill this one?

That was a time of overthinking cartoons and trying to take them at least semi-literally. If a door with glass windows in it lit up like a pinball machine when the doorknob was pulled, why was it built to do that? Where do giants get books, newspapers, watches and other goods made to scale? How did Coyote pay for all that stuff he was ordering from Acme (and where did they send it)? Hillbilly Bluto pounding Popeye into a flat round target I accepted, but how did all the merchandise in Popeye’s rolling department store fit before it unfolded?

The Venus de Milo scene indicates that it would be possible, in the world of this cartoon (or, I should say, the world of the dream sequence in this cartoon!) that the A. Powello statue could be put back together before being brought back to life.

I wonder what happened that lead to only Clampett getting credited.

“Can you taste the difference?” could be a reference to the brand of lipstick that the Gorgon is using.

I wonder why a lot of people call Robert Cannon “Bobe” when he was never credited as such in Warner cartoons.

According to Adam Abraham’s “When Magoo Flew”, this is the history behind Cannon’s nickname:

“Since the animation business enjoyed a panoply of persons named Robert or Bob – McKimson, Clampett, Givens, and others – Cannon soon aquired the nickname ‘Bobo,’ which derived from a popular song. He thought that ‘Bobo’ was a bit too cute and clownish, according to his daughter; so his name was modified to ‘Bobe,’ and Bobe Cannon he remained.”

Bob Clampett does not receive enough credit. Almost all of my favorite Daffy Duck cartoons are directed by him. The zanyness of the cartoon reflects Clampett much more than Jones.