A Word of Introduction:

Ever get the feeling of deja-vu while you’re watching a cartoon you know you’ve never seen before? Something about it seems so familiar in mood or style, but you can’t quite place your finger on it. Not surprising. Considering that the animation industry learned early on that, while it may be possible to copyright or trademark a character, it wasn’t so easy to protect a story concept. A scenario or setting for the action. Or even a distinct series of gags. Not to say that the animation industry was unique in the habit of “borrowing” from one another. Various branches of comedy had been doing it practically since comedy began.

The popularity of Sennett “knockabout” comedies brought about any number of avid imitators, including some who would go so far as to parallel the studio’s trademark “little tramp”, Chaplin. Abbott and Costello and the Three Stooges would liberally lift material from vaudeville. And Milton Berle would live on a reputation of stealing from everybody! So the fact that many major animation houses engaged in periodic gentle forms of plagiarism should not truly be viewed as a cardinal sin – it was all part of the comedy game in the days before litigation of every similarity became the norm. Certainly there were rare exceptions when some expression of comedy genius had its day in court – case in point being Harold Lloyd v. Columbia short subjects division and Clyde Bruckman, for lifting a routine from Lloyd’s “Movie Crazy” into the Stooges’ “Loco Boy Makes Good” – the outcome of which has been long rumored to have been the motivation for Bruckman’s suicide. But such instances were the rare exception to the rule, and most comedians, as well as animators, wouldn’t have given the idea of looking over each other’s shoulder at the rival’s material a second thought of remorse.

The popularity of Sennett “knockabout” comedies brought about any number of avid imitators, including some who would go so far as to parallel the studio’s trademark “little tramp”, Chaplin. Abbott and Costello and the Three Stooges would liberally lift material from vaudeville. And Milton Berle would live on a reputation of stealing from everybody! So the fact that many major animation houses engaged in periodic gentle forms of plagiarism should not truly be viewed as a cardinal sin – it was all part of the comedy game in the days before litigation of every similarity became the norm. Certainly there were rare exceptions when some expression of comedy genius had its day in court – case in point being Harold Lloyd v. Columbia short subjects division and Clyde Bruckman, for lifting a routine from Lloyd’s “Movie Crazy” into the Stooges’ “Loco Boy Makes Good” – the outcome of which has been long rumored to have been the motivation for Bruckman’s suicide. But such instances were the rare exception to the rule, and most comedians, as well as animators, wouldn’t have given the idea of looking over each other’s shoulder at the rival’s material a second thought of remorse.

This series of articles is not so much intended to map the path of thievery, as to document the development of an idea or concept from studio to studio. While some lower-end studios developed a bit of a reputation for always being derivative of others (the most guilty party being Terrytoons, not only freely dipping into the trunk of ideas of others regularly, but equally commonly recycling its own gags over and over again, drawings (and sometimes even soundtracks) and all, in multiple episodes over several decades), others showed ingenuity. Finding a good setup in something they had probably viewed on one of their off-days at the local Bijou matinee, they cleverly asked the question, “How could I have done that better?” Tex Avery was one of these latter types. Columns in this series will touch on some notable instances where Avery liked something from another filmshop, decided to try his own hand at it – and, unlike the habit of most modern sequels, topped the original considerably, with original gag material on top of the old story framework. Even a “borrow” could spawn creativity in the good old days, when in the right hands.

The second objective of these articles will be not only to follow the embellishments as ideas passed through diverse hands, but to attempt to pinpoint the nucleus of where the progression started from in the first place. Some of this effort at discovering an origin point may be educated guesswork. While scads of “talkies” abound in animation archives, comparatively little is documented or available for review from the history of the animated silent cinema. Filmographies of such fertile arenas for creative material as “Felix the Cat”, “Mutt and Jeff”, and “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit”, as well as the less fertile “Krazy Kat” and Terry “Aesop’s Fables”, are studded with holes – films not only lost, but in some instances (as in most attempts I’ve seen to document Felix release schedules) where even the titles of the episodes remain unknown.

The second objective of these articles will be not only to follow the embellishments as ideas passed through diverse hands, but to attempt to pinpoint the nucleus of where the progression started from in the first place. Some of this effort at discovering an origin point may be educated guesswork. While scads of “talkies” abound in animation archives, comparatively little is documented or available for review from the history of the animated silent cinema. Filmographies of such fertile arenas for creative material as “Felix the Cat”, “Mutt and Jeff”, and “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit”, as well as the less fertile “Krazy Kat” and Terry “Aesop’s Fables”, are studded with holes – films not only lost, but in some instances (as in most attempts I’ve seen to document Felix release schedules) where even the titles of the episodes remain unknown.

Only the Fleischers seem to be reasonably well documented. We can only speculate in the dark from this void how many of the situations and tropes we have familiarity with from the sound era may have first developed in silents. It is likely there was some crossover from one era to another. (How else can you explain identical drawings of a crowded New York subway terminal turning up in Mutt and Jeff’s The Globe Trotters and in the “talkie” Columbia Krazy Kat, The Broadway Malady?) Any devotees of the silents remembering or having access to rare prints that might reveal earlier originations for the concepts to be discussed in this series are invited to share their input. For that matter, there may at times be isolated gags or sequences I may not be aware of in the talking era. So, your comments and contributions are welcome – there’s always room for another Sherlock Holmes in the hunt.

On a final note of introduction, there are a few things this series will attempt in earnest to avoid. For example, internal recycling of material within the same studio will largely be avoided. We will not be covering every color remake of a black-and-white original. Nor every instance where Tex Avery repeated the same gag of characters chasing each other through hallways with an endless number of doors. Nor how many times the coyote plummeted down the same canyon in quest of the Road Runner. A catalog of reused gags and footage is far beyond the capabilities of this series – and overbroad enough to drive the average animation buff to distraction.

A second aspect of derivative “inspiration” which will not be covered here is the seemingly endless number of titles parodying famous fairytales or well-known literary works. How long a list would be needed, for example, to itemize every instance where someone did a “Jack and the Beanstalk” spoof? While I could probably think of at least a couple of dozen off the top of my head, I believe I and the reader have better ways of spending our time, and leave such Herculean efforts to a future writer. Instead, I will attempt to focus attention upon non-literary based original scenarios, that somehow lifted the imaginations of both audience and animators alike to be fallen back upon again, and again – and sometimes again and again – as a dependable source of entertainment.

With this framework established, let’s launch down Trail #1:

Magnetic Personalities:

The simple concept of the common magnet. Usually depicted as a horseshoe variety, though with the advent of the “space age” some depictions got a little more “high tech” – more on this below.

Where did this first develop into comedy? Though my knowledge of live-action one and two-reelers of the teens and twenties isn’t as comprehensive as I wish it could be, the king of all instances I know where the magnet first graduated to a prominent “star” prop would be Snub Pollard’s bravura performance as an eccentric inventor in Hal Roach’s Pathe one-reeler, It’s a Gift (1923). Here, Pollard solves the transportation problem by visiting his garbage can, where he changes the lettering on the can from “garbage” to “garage”, causing it to open a side hatch revealing a one-passenger vehicle shaped like a silver bullet. No engine, of course – that would cause pollution! Snub’s entire propulsion method consists of a large horseshoe magnet resting in the cockpit of the contraption. Just wait for a passing flivver, take careful aim – and leave the driving to the other fellow, as he pulls you along behind as so much extra ballast. Change directions? Easy. Just re-aim your magnet at another flivver going the other way. When Snub finally has to make an escape from his pursuers, just build up enough speed, dump the magnet, and sprout wings for a quick aerial takeoff!

Where did this first develop into comedy? Though my knowledge of live-action one and two-reelers of the teens and twenties isn’t as comprehensive as I wish it could be, the king of all instances I know where the magnet first graduated to a prominent “star” prop would be Snub Pollard’s bravura performance as an eccentric inventor in Hal Roach’s Pathe one-reeler, It’s a Gift (1923). Here, Pollard solves the transportation problem by visiting his garbage can, where he changes the lettering on the can from “garbage” to “garage”, causing it to open a side hatch revealing a one-passenger vehicle shaped like a silver bullet. No engine, of course – that would cause pollution! Snub’s entire propulsion method consists of a large horseshoe magnet resting in the cockpit of the contraption. Just wait for a passing flivver, take careful aim – and leave the driving to the other fellow, as he pulls you along behind as so much extra ballast. Change directions? Easy. Just re-aim your magnet at another flivver going the other way. When Snub finally has to make an escape from his pursuers, just build up enough speed, dump the magnet, and sprout wings for a quick aerial takeoff!

But when did the magnet first reach the same prominence in cartoons? I am unaware of any instances of its use in surviving silent cartoons. (A “Want list” of one online collector suggests the existence of a Paul Terry Aesop’s Fable which he refers to only as “Cat and the Magnet” – no corresponding title information appears on IMDB or other sources. Anyone have any information?) Perhaps the move to animation didn’t come instantly because of the difficulty of visualizing and drawing the effect of normally invisible magnetic rays. It appears that approximately a decade passed without much action.

Max Fleisher deserves an honorable mention here, for reference to the subject in two cartoons which were essentially originals and not influential to any noticeable degree on the rest of the industry. These episodes are “off” the trail. First comes Betty Boop’s Ups and Downs (1933), one (if not the) earliest uses of the prop in sound animation – but for a different purpose than usual. Here, the planetary residents of the cosmos converge for the unusual event of an auction of the planet Earth, presided over by auctioneer Moon. Saturn (portrayed as a stereotype Jewish character with Yiddish dialect) oddly wins the auction with the lowest bid. Upon taking possession, he decides to try an experiment – take out the Earth’s “magnet” (depicted as a giant horseshoe magnet, symbolizing gravity) and see what happens. Of course, in typical surreal fashion, everything on Earth starts floating skyward into the stratosphere. At the end of the film, Saturn is seen with the Earth’s magnet attached to his backside, complaining, “I knew I got stuck”. The magnet is grabbed back by a giant hand from the center of planet Earth – and gravity is restored. No derivatives from this far-out idea are known in other cartoons.

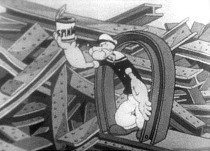

Fleischer’s second honorable sidelight comes from the supercharged fists of Popeye, in Bridge Ahoy (5/1/36). Bluto has just picked up and destroyed the suspension bridge Popeye is building to beat the overpriced fare of Bluto’s Ferry. Popeye gobbles his spinach, and with one sock launches Bluto into his ferry, across the bay, and aground smack into the side of a building. Popeye then picks up one girder from the rubble of his bridge, bending it around himself into a “U”. Taking an extra dose of spinach, the energy from inside him flows into the girder, magnetizing it. With one flying leap, Popeye jumps across the bay, aiming the magnet behind him. The power of the magnet picks up every scrap of debris – not only reassembling the portions of the bridge that were previously constructed, but completing the whole project, with autos already traveling on it in full lines of traffic in both directions! (If it was so easy, Popeye, why did you make us wait through seven minutes of watching you do things the hard way?) Because of the super-powered nature of this feat, the gag was not apparently repeated by other studios – with the exception of possible inspiration for one of the last entries in our trail from the 1960’s – read on below.

Fleischer’s second honorable sidelight comes from the supercharged fists of Popeye, in Bridge Ahoy (5/1/36). Bluto has just picked up and destroyed the suspension bridge Popeye is building to beat the overpriced fare of Bluto’s Ferry. Popeye gobbles his spinach, and with one sock launches Bluto into his ferry, across the bay, and aground smack into the side of a building. Popeye then picks up one girder from the rubble of his bridge, bending it around himself into a “U”. Taking an extra dose of spinach, the energy from inside him flows into the girder, magnetizing it. With one flying leap, Popeye jumps across the bay, aiming the magnet behind him. The power of the magnet picks up every scrap of debris – not only reassembling the portions of the bridge that were previously constructed, but completing the whole project, with autos already traveling on it in full lines of traffic in both directions! (If it was so easy, Popeye, why did you make us wait through seven minutes of watching you do things the hard way?) Because of the super-powered nature of this feat, the gag was not apparently repeated by other studios – with the exception of possible inspiration for one of the last entries in our trail from the 1960’s – read on below.

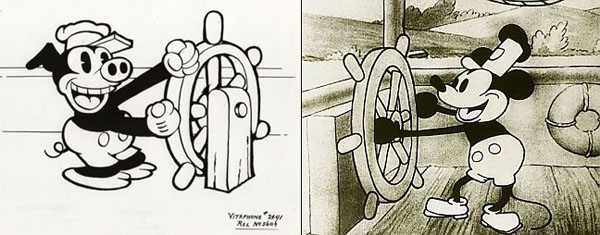

Then, someone at the “Mouse House” (Disney, that is, not Paul Terry) decided to take a crack at it. Undoubtedly remembering the outrageous strength of the hand-sized Pollard “puller”, the Disney gang decides to place such a troublesome tidbit into the hands of the studio’s lead trouble-finder – Donald Duck, in his first starring appearance without Mickey (even though the cartoon, for lack of an established series banner at the time for Donald or any other spinoff character, continued to be marketed and billed as a “Mickey Mouse”). Donald, however, not yet being known for handling a whole film solo, shares equal spotlight with another trouble-prone member of the Mickey universe – ever-faithful pooch Pluto. Thus, the simple title, Donald and Pluto (9/12/36).

The magnet, however, takes center stage from practically the first shot of the picture, although it is not yet seen. All we see is electrical “rays”: pulling out of the bag of “Donald Duck, Plumber” a heavy metal hammer. Up it flies into the air and out of frame, as the next shot reveals Donald on an upper platform, holding our standard red horseshoe magnet, to which the hammer loudly clanks in attraction. While Donald applies his retrieved tool to his plumbing task, he does not notice the vibrations from the hammer blows are dislodging the magnet from the pipe to which he has affixed it – causing it to fall below, where Pluto is attempting to have his lunch – a soup bone – from a metal doggie dish. One thing leads to another – first, the dish is stuck to magnet, then Pluto’s snout gets caught between them – then Pluto dislodges the magnet only long enough to get the bowl behind him, with himself between the bowl and the magnet. The dish is pulled forward to hit his rear end., causing Pluto to open his mouth in surprise – and the magnet flies inside, swallowed. Now Pluto must deal with his new “magnetic” personality, as everything of metal seems to find its way to him – pots, pans, clocks (wall and alarm models), knives, cleavers, and finally all the nails out of Donald’s ladder, bringing the duck into the fray as he falls into a washing machine.

Donald gives chase, but loses sight of Pluto just long enough for the dog to run to the roof, while Donald mistakes a lump in the rug downstairs for the mischievous mutt. Pluto sits down on the roof – and suddenly Donald’s hammer drags the mallard up to the ceiling. A hilarious battle of wits ensues as each of them tries to figure out what is holding them up (or down), and how best to break the attraction. For every action, there is an equal and opposite (and usually devastating) reaction to the other – until Pluto finally drags Donald past the roof edge, out a window, and underneath the rungs of an extended ladder Pluto’s walking on. The trouble now revealed, Donald launches into a tirade, causing the ladder to topple from the roof and to plunge both of them back into the basement. As Pluto lands, the ladder collides with his rear-end, knocking the magnet out of his gullet. Donald is caught between the magnet and the basement boiler – and gets pinned to it by his neck. Every one of his tools follows swiftly, with a large adjustable wrench landing on his beak and clamping it shut. Pluto, now reunited with his bone and dog dish, thanks Donald with several friendly slurps – while the helpless duck proves once again that he may be able to dish it out, but just isn’t happy when he has to “take it”.

Donald gives chase, but loses sight of Pluto just long enough for the dog to run to the roof, while Donald mistakes a lump in the rug downstairs for the mischievous mutt. Pluto sits down on the roof – and suddenly Donald’s hammer drags the mallard up to the ceiling. A hilarious battle of wits ensues as each of them tries to figure out what is holding them up (or down), and how best to break the attraction. For every action, there is an equal and opposite (and usually devastating) reaction to the other – until Pluto finally drags Donald past the roof edge, out a window, and underneath the rungs of an extended ladder Pluto’s walking on. The trouble now revealed, Donald launches into a tirade, causing the ladder to topple from the roof and to plunge both of them back into the basement. As Pluto lands, the ladder collides with his rear-end, knocking the magnet out of his gullet. Donald is caught between the magnet and the basement boiler – and gets pinned to it by his neck. Every one of his tools follows swiftly, with a large adjustable wrench landing on his beak and clamping it shut. Pluto, now reunited with his bone and dog dish, thanks Donald with several friendly slurps – while the helpless duck proves once again that he may be able to dish it out, but just isn’t happy when he has to “take it”.

Ben Sharpsteen directs this splendidly creative episode, though no source appears to reveal the script’s author (this being several seasons before full credits would appear on a Disney short). What is uncanny about this classic is that in approximately 8 minutes flat, the film appears to invent every cartoon convention that would characterize the magnet cartoon up to the present day. The animation of “electric” rays to give the pulling power of the prop a visual element. Is well perfected The surprising effects of a magnet when swallowed. Pursuit of a principal character by various lethal weapons made of metal. Efforts of a labored “nitwit” brain to outwit the power. And the surprise to a character of being manipulated by hidden forces from the other side of a wall or ceiling. Everything is there! As could always be expected from Disney of this period, the animation itself is equally stellar. Pluto exhibits all of his “thinking man’s mutt” attitudes in classic fashion, as we read his thought processes and frustrations thoroughly through well-orchestrated pantomime. Particularly notable are a delightfully rubbery set of facial reactions as he is cornered and tormented by an alarm clock with an affinity for his posterior, and tries desperately to escape his confines. Another classic expression is registered as he finds a single brief moment of peace, pants a happy open-mouthed smile – only to have his dog dish reappear with a clank affixed to his bottom – and breaks the fourth wall with a look of total disgust to the audience, as if to say, “Oh, no, not again!”

I have rarely if ever seen a write-up on this cartoon, excepting the usual Wikipedia and IMDB pages commonplace to virtually every Disney cartoon. So it’s unknown how well this film did in bookings. However, if longevity in other formats is a measure of success, this title appears to have been issued in at least two home movie editions, the first presumably from Hollywood Film Exchange, possibly only in digest form, and then in complete form when Disney started its own home movie division, staying in catalog from beginning to end of 8mm/Super 8 production. Obviously, Disney had a respect for it. And it seems to have been an appropriate launching pad for the later-to-be-established Donald Duck series once the studio changed distributors to RKO. Other studios apparently noticed, too.

Frank Tashlin was the first. Taking a leaf from the finale sequence of D&P, Tashlin incorporates the magnet into a wild series of gags above and below the water to rig a skating contest – in Warner Bros. Merrie Melodies entry, Cracked Ice (1938). The first target of the magnet in question here is the same as in Disney’s – the dog dish of a St. Bernard whom returning porker W.C. Squeals (previously seen in Friz Freling’s At Your Service, Madame (1936) seeks to attract to him to get his brandy barrel. However, the dog and pig crash, sending the magnet falling through a hole in the ice, to become lodged on the stomach of a passing fish. Through the ice, the magnet first attracts an axe, then Squeals’ skates, leading the pig on a merry and chaotic chase while the fish below the ice is pursued by a bigger, hungrier fish. The melee wins Squeals a figure skating championship. On winning the loving-cup trophy, Squeals uses it to pour in for consumption the contents of the brandy barrel (the real prize he’s been seeking all along), only to have the whole loving cup drawn away from him and off into the distance by the same fish below the surface. Definitely derivative of the “above and below” aspects of the roof and ceiling sequence of its predecessor – but a funny adaptation to a different locale and setting.

A Good Time For a Dime (Disney RKO, Donald Duck, 1941, Dick Lundy, dir.) – Not the center of attention, but a magnet makes a brief appearance in a reasonably creative use. Donald is playing an arcade Claw Machine – and having little luck. (So far, he’s only succeeded in getting a bottle of ink – which the stopper fell out of, pouring ink into his hat.) Spotting a large magnet among the prizes, Donald hatches an idea. Aiming the claw at the magnet first, he applies a little “body English” to the machine – tilting and shaking it every which way – until the magnet has picked up every metal prize in the machine. They all are emptied into the prize slot, with Donald cheering “Oh, boy! The jackpot!” One prize, however, was not made of metal – a perfume bottle with atomizer. The claw closes on the spray bulb, shooting perfume down the prize chute, which Donald inhales. It’s not his favorite aroma, and Donald is unable to hold back a tremendous sneeze – which sends all his prizes flying back up the chute, landing right where they started. Donald’s face turns beet red in a classic “slow burn”, as the sequence ends.

Under the Spreading Blacksmith Shop (Universal/Walter Lantz, Andy Panda, 1942 – Alex Lovy, dir.) – We’re only six years into the genre – and for the first time, the gags are already feeling old. Andy’s Pop, village blacksmith, is constantly pestered by Andy’s insistence that he too could shoe a horse. Papa resorts to a horse costume to test Andy out – handing Andy a note asking Andy to stake him to some new shoes – signed, “Charlie Horse”. (Was Bob Clampett watching?) After some belabored escapades by Papa, we get an absolute lift of the opening premise of Pluto – Papa caught on the floor, between the proverbial “rock and a hard place” – a steel anvil behind him, and a fallen box of magnets in front of him. (Why does Papa just happen to have these on supply in his shop?) Figuring that many magnets are funnier than one, Lovy reprises Pluto, having the anvil come loose, bump Papa in the rear end so he opens his mouth – and swallow the whole box of magnets one by one. Poor timing defeats nearly every opportunity for a laugh as the anvil pursues Papa down a lane and into the woods. Only two gags seem to mildly work – Papa hiding behind a tree, with the anvil creeping out from behind to follow him on humanized “tiptoes” – and Papa smashing the anvil with an axe (strong axe blade!), only to have the magnetism reassemble it instantly. Papa finally trades pursuers by losing the anvil stuck in a door, but attracting all the red-hot horseshoes from the day’s supply. Papa escapes his costume, as Andy catches the still-galloping skin and successfully shoes it, proving himself. Papa exits by the nearest country road, the horseshoes still in “hot” pursuit, yelling, “Andy, tell your mother I won’t be home for dinner.”

Lucky Lulu (Paramount/Famous, Little Lulu, 6/30/44 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – One of the lesser-known (undeservedly so) Little Lulu’s, never reissued to home video, builds about half its plot around our concept – with a bit of a twist not generally explored by other studios. Lulu’s been having a bad week, getting spankings for getting into unintended mischief, which she regularly documents into her diary with a rubber stamp. Mandy (Paramount’s version of Mammy Two Shoes, but with a face) suggests she get herself a good luck charm. Lulu selects a lucky horseshoe – except it’s still on the horse. She attempts to extract it with a fishing pole and our old faithful horseshoe magnet. When it still won’t pull off, she adds the insurance of a stick of dynamite. Blown free, she attempts to separate one “shoe” from the other. When she does comes the unexpected surprise – the real horseshoe has now become magnetized too. It drags her onto a tractor’s metal treads. She frees herself and tries to hurry home – only to unceremoniously undress the local traffic cop of his badge, whistle, handcuffs, buttons, etc. Further taking into tow a clothing store mannequin, she hides behind a truck, but is lifted into the air by her lucky charm to collide with and loosen the truck’s rear latch, releasing an entire shipment of rolling watermelons (Famous takes a leaf here from a second previous inspiration – the runaway beer barrel sequence from the Three Stooges “Three Little Beers” (1935)). Needless to say, our heroine still gets her daily spanking.

Buckaroo Bugs (Warner, Merrie Melodie, Bugs Bunny – 8/26/44) follows closely on the heels of Lulu, bringing Bob Clampett into the fray for a brief throwaway gag, repeated twice. Bugs Bunny, as a western carrot thief, frustrates would-be hero Red Hot Ryder by robbing him twice, by means of pulling out our trusty prop once again, magnetically taking from Ryder everything made of metal, including his teeth fillings and his belt , leaving him briefly bottomless save for a well-placed fig leaf. (A double-borrow, lifting the fig-leaf gag from Tex Avery’s “All This and Rabbit Stew” (1941), where Avery gave it a better pay-off with “Sambo”’s curtain-line, “Well, just call me Adam!”)

Mess Production (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 1945 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – only a brief mention for this otherwise classic Popeye Technicolor tour de force. A magnet figures into this one in only one sequence, more as a straight prop than a real gag. Popeye has just rescued a stunned sleepwalking Olive by fishing for her in a steel factory with a large metal crane. Bluto foils his rescue by grabbing the clamshell of the crane with a giant industrial magnet, and yanking the crane’s jaws open in a tug of war with Popeye. That’s all.

Trap Happy (MGM. Tom & Jerry – 6/20/46, Hanna/Barbera, dir.), brings Tom and Jerry to their first encounter with the inevitable “attraction” – but it’s not Tom that brings it about. Instead, it’s tough cat Butch, who Tom’s hired as a mouse exterminator. In a very brief introductory sequence, Butch quickly locates Jerry upon his arrival by taking a nut bolt, painting it to look like piece of swiss cheese, and luring Jerry to swallow it. Then pull out our favorite prop to drag Jerry out of the mousehole. A straight reworking of the original Pluto scenario, but with the magnet on the outside rather than the inside. The gag was reused verbatim years later by Tom himself in “Mouse for Sale” (1955) . But this would not be the end of T&J’s magnetic escapades – read on below.

The Tortoise Wins Again (Fox, 8/9/46 – John Foster, dir.) adds Terrytoons to the list (you knew they’d get in there sooner or later). No one’s hiding-the-ball here – it’s a straight steal of the ending sequence from “Cracked Ice”, used as the ace-in-the hole for the turtle to win a skating race with his old nemesis the hare. This cartoon is an equal-opportunity rip-off festival. See how many gags and ideas you can find lifted from The Tortoise and the Hare (1935), Tortoise Beats Hare (1941), Put-Put Troubles (1940), just to name a few. Timing on this title, however, is exceptionally crisp, and Philip Scheib’s score unusually lively. Foster’s rule of thumb on this one seems to have been, you can soften the blow of swiped material if you give it to the audience at breakneck speed. To a degree, he’s right. The amalgam still develops a few good smiles here and there.”

Old Rockin’ Chair Tom (MGM, Tom & Jerry, 9/18/48) – One of the less-frequently screened T&J’s, due to a sizeable role for Mammy Two Shoes. Mammy’s fed up with Tom again, and has found a younger, more energetic cat to take his place – an orange tabby named “Lightning”. He not only sends Tom packing, but makes short work of Jerry too. Our heroes engage in one of their rare “team-ups’, joining forces to thwart a common enemy. Their method is a magnet and a flat iron. In a direct lift from the setup for “Donald and Pluto”, Tom holds the magnet behind a sleeping Lighting, while Jerry opens his mouth – making Lightning swallow the flat iron Jerry’s left in front of him. T&J take turns wielding their horseshoe weapon to drag Lightning all over the place, letting him slide face-first into Tom’s extended fist, crash through a piano, then (in another lift from “Donald and Pluto”) get stuck by his rear end to a wall, behind which Tom twirls and maneuvers the magnet to make Lightning dance, twirl, and stand on his head for repeated pounding. When Lightning can’t save Mammy from Jerry in the kitchen, she screams for Tom – and Tom has his old job back. One final nice touch is when Tom takes charge of evicting Lightning, rearing back for a good swift kick – but forgetting the flat iron is still inside Lightning’s rear end, with a surprise painful result to Tom’s foot. This one comes about as close as any to lifting the entire scenario of Donald and Pluto for its major plotline – I guess they figured with over a decade of time passed between them, maybe nobody would notice.

Goony Golfers (Terrytoons, 12/1/48 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – A lesson in how to handle a concept – all wrong. Heckle and Jeckle try to put in his place a duffer bulldog, whose errant shots keep disturbing the birds’ treehouse gin rummy game. Volunteering as caddies , the two set about lousing up his day. The premise is derivative – see Donald’s Golf Game (1938). The gags are derivative, – for example, borrowing the draw-an-eyeball -on-the-golfball-stuck-in-a-character’s -eye gag used by Jerry in Tom & Jerry’s Tee For Two (1945). Also using for the third time a trademark Terry ending – the “bomb within a bomb within a bomb” Russian nested doll-style gag used every year for the previous two seasons (previously used in Heckle and Jeckle’s The Intruders (1947) only a season before, and before that by Gandy Goose in Peace Time Football (1946)). But surprisingly, the use of a magnet in this cartoon is a seemingly original concept – I am unaware of its previous use in a golf context.

What is decidedly wrong, however, is the execution of the gag (they execute it all right – just like a headsman!), and their entire ignoring of the physics of how to set the situation up. As the bulldog sets up for a perfect putt (clearing a path in the green with a hair trimmer – another direct lift from Donald Duck parting the green with a comb in Donald’s Golf Game), Jeckle opens the bottom of one of the bulldog’s clubs, saying to Heckle, “Let’s have that magnet, old boy. He’s too confident.” But the club they put the magnet in is a wood. Who would use a wood on a putting green?? When the dog attempts to putt, the ball is magically attracted to the club. Why? Since when is the core of a golf ball made of metal? As the dog ponders what’s going on, his dentures fly out of his mouth and stick to the club too. Again, why? They’re not depicted as containing metal fillings, so where’s the source of attraction? At least the last few objects attracted to the dog are made of metal – but it’s too late to save this fouled-up sequence, or this tired-feeling cartoon. (It would have to wait a few years for this situation to be rescued by a proper presentation in “Woodpecker in the Rough”, discussed below.)

Swallow the Leader (Warner, 10/14/49 – Robert McKimson, dir.) – An unnamed Mckimson cat (approximately the same as used in “Playing the Piper”, “A Fractured Leghorn”, “It’s Hummer Time”, and “Early to Bet” – McKimson must have thought he’d be the next Sylvester) stalks San Juan Capistrano for the dependable arrival of his prospective next meal – the first swallow. In another harken to the “swallowing” trope from Donald and Pluto, the swallow fools him by painting in full color an iron bird from the statuary of a birdbath, which the cat willingly devours. Producing a “Super-Magnet”, the bird drags him over rooftops, ladders (you’re remembered again, Pluto) and other terrain, and finally off a roof. The cat falls, but grabs a mirror (why does this ward off the rays?), and hides behind it, avoiding the magnet’s effect. Realizing the jig is up, the bird flings the magnet at the cat. The cat ducks, and it lands behind him. Now on the same side of the mirror as the cat, the magnet flips around and comes back. The cat runs and hides behind a flagpole, but is caught as the magnet does a “ringer” on the pole, attaching itself to the cat’s rear end. Now the most improbable twist of all. The swallow has in this short span of time constructed a large wooden ramp in from of the cat, placed one end of a teeter-totter board under his feet – plus loaded the ramp with a series of large boulders, and affixed a fire-alarm style bell to the top of the flagpole. The miraculously-strong swallow pushes one boulder after another onto the teeter-totter – operating it as a carnival “high striker” and making the cat repeatedly “ring the bell”. Fast paced and funny – only as long as you don’t think about it too hard.

A Ham In a Role (Warner, Goofy Gophers, 12/31/49, Robert McKimson, dir.) – McKimson is back again two months later, with his first crack at the “Goofy Gophers” series – in a script suspected to be inherited by Bob from Arthur Davis’s now-closed unit. Another reworking of Donald and Pluto’s “both sides of a wall” concept, but with a clever twist. The Shakespearian-influenced dog who was the gophers’ regular nemesis in their early episodes has taken up residence in his country abode to rehearse the works of the “immortal bard”. Donning a suit of armor, he recites his soliloquy (I’m not that much of a Shakespeare buff – someone tell me from which play he’s reciting). The gophers, who are determined to rid themselves of this pest to reclaim the house for themselves, retreat to opposite positions – one in the attic, the other in the basement. Both produce magnets. In some wonderfully dimensional scenes, each one takes alternating turns dragging the helpless dog along both the floor and the ceiling, culminating with a long shot where the dog is seen ricocheting between these extremes like he’s in a pinball machine, to a wonderful array of Treg Brown sound-effects, only to finally crash into an ice box. This one always gets me laughing.

Mouse and Garden (Fox/Terrytoons, Little Roquefort, 10/1/50 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – Roquefort’s building a mini “model home” around his mousehole. Percy, guard of the construction equipment, uses a magnet to steal away his hammer. The hammer and magnet get looped around Percy’s nose. As he gets loose, Roquefort knocks him backward with a bent sawblade – and Percy swallows the magnet (here we go again, Pluto). Roquefort unleashes a barrel of nails to fly after him, which enter through a back door when Percy ducks in a building, hit him in the rear-end, and knock the magnet out, where they all fly to stick to the magnet (a revisit to Pluto getting hit by the ladder). Standard Saturday morning fare.

The Framed Cat (MGM, Tom & Jerry, 10/21/50 – Hanna/Barbera, dir.) – In what would be their finest use of magnetism, Tom & Jerry once again resort to the hidden power. Tom has just covered up his own theft-in-progress of a chicken leg from Mammy Two-Shoes’ pantry by placing the incriminating appendage in Jerry’s paws. Jerry seeks revenge, and decides to frame Tom the same way, by making Spike the bulldog think Tom is trying to steal his bone. Jerry’s climactic idea is to smuggle a hand-drill into Spike’s doghouse, hollow out the center of his bone and replace it with a large metal screw – then get Tom to swallow a magnet (yes, again!). The bone is drawn from Spike’s doghouse into the jaws of helpless Tom. Spike grabs the bone, but it’s instantly drawn back into Tom’s mouth. Spike again removes it, and this time Tom’s rear-end pivots toward it. Tom spins his posterior back the other way, and Spike’s arm is drawn to Tom. The two engage in a dance of positions, neither able to figure out what is happening (a scene owing much to the “Pluto and the alarm clock” sequence of “Donald and Pluto”).

Tom runs for it, flinging the bone out of the yard and into the street. Spike outruns the bone, and attempts to snap at it – only to have the bone drawn from his lips before he can snap, back across the street and up against the picket fence. Spike makes another lunge, but only comes with a mouthful of fenceposts as the bone flips over the fence back into the yard. Spike finally catches up with the bone in midair – but is dragged into a tree, with his tongue well stretched out of shape as the bone escapes his grip. The bone hits Tom butt-first. Tom runs for his life, the bone following mere inches away, and Spike mere inches behind that. Jerry has taken refuge in a poor hiding place – a tin can, and realizes his mistake too late as his triumphant laughing devolves into a look to the audience which can only translate as “Uh oh.” His can, with him inside, is drawn out of frame by the electric rays. We climax with a long shot to horizon, as Tom, bone, Spike, and Jerry’s can, disappear down the road in one of those cartoon chases that never knows an end. Because the magnet was by now a well-treaded cartoon cliche, this episode falls just-short of ranking as an all-time T&J classic, but is certainly a worthy “runner” up.

Tom runs for it, flinging the bone out of the yard and into the street. Spike outruns the bone, and attempts to snap at it – only to have the bone drawn from his lips before he can snap, back across the street and up against the picket fence. Spike makes another lunge, but only comes with a mouthful of fenceposts as the bone flips over the fence back into the yard. Spike finally catches up with the bone in midair – but is dragged into a tree, with his tongue well stretched out of shape as the bone escapes his grip. The bone hits Tom butt-first. Tom runs for his life, the bone following mere inches away, and Spike mere inches behind that. Jerry has taken refuge in a poor hiding place – a tin can, and realizes his mistake too late as his triumphant laughing devolves into a look to the audience which can only translate as “Uh oh.” His can, with him inside, is drawn out of frame by the electric rays. We climax with a long shot to horizon, as Tom, bone, Spike, and Jerry’s can, disappear down the road in one of those cartoon chases that never knows an end. Because the magnet was by now a well-treaded cartoon cliche, this episode falls just-short of ranking as an all-time T&J classic, but is certainly a worthy “runner” up.

Stooge For a Mouse (Warner, Sylvester, 10/21/50, I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) -Two magnet cartoons released on the same day? Really! In an episode which lifted an entire plot premise from another studio (this is essentially a remake of Herman the Mouse’s Noveltoon Cheese Burglar (Paramount, 1946. I. Sparber. dir.), something of a cult classic for its heavy use of loose Jim Tyer animation), an unknown mouse decides to break up an inconvenient friendship between tough bulldog Hector (in this episode renamed Mike) and sputtering Sylvester the Cat, by reminding the dog of their roles as natural enemies. Through subliminal calls placed by way of a telephone receiver dropped through a hole in the ceiling next to “Mike”’s ear, and well-timed placement of various lethal weapons into the paws of sleeping Sylvester, the dog is led to believe the cat is trying to do him in.

Magnetism provides the finale sequence, as the mouse ties a “loaded” boxing glove – full of horseshoes (Andy and Lulu, you’ve just been remembered) onto the unconscious cat’s paw. Then, producing a magnet in the basement (Gophers, you’re remembered, too), the mouse runs from one end of the house to the other, dragging a helpless Sylvester above with him – to smash the bulldog a good one in the kisser (a reversal of Lightning being dragged into Tom’s fist in “Rockin’ Chair” above). The bulldog responds – instead of seeing the blows, Freleng engages in his trademark touch of scoring bigger laughs when the crucial action is left to the imagination. We see the mouse’s view from the basement, as the magnet zips backward in perspective to come to a stop where it began on the other side of the house. Above, we finally see Sylvester, smashed against the wall and seeing proverbial stars. The mouse repeats the process – again and again and again – with the magnet zooming back and forth from one extreme to the other – until we fade to denote the passage of time, finally seeing above both Sylvester and Mike in a daze, frazzled, beaten, and out like a light.

Unlike its Herman predecessor, this version of the story doesn’t end on a happy note for anyone. The mouse now dances a little trot, heading for his objective, the household cheese. We cut to a shot of the basement, where the unattended magnet suddenly develops another attraction and rises straight up to face the underside of the floorboards. Cutting to a shot of the living room, a metal lighting fixture on the ceiling is seen vibrating from the attraction below – and is pulled loose from its moorings. It crashes on the mouse passing below, who is also knocked into a daze, and stumbles just far enough to fall unconscious in a heap with the dog and cat. Iris out. (Freleng liked this finale, and the whole plot setup, so well that he remade it two more times in his career – first as Bugs Bunny’s Bugsy and Mugsy (1957), and then as one of the infamous “Dogfather” series of remakes under his own banner, Heist and Seek (1974).)

Cat-Choo (Paramount/Famous, Buzzy and Katnip – Noveltoon, 10/12/51, Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Typical but fun installment in the “Buzzy as the sure cure for any ailment of Katnip” formula. This time, Buzzy’s ice skating on a frozen bird bath. Lifting from “Cracked Ice”, Katnip ties a magnet to a clothesline extending over the birdbath, wheels it into position over Buzzy, and picks him up by the skates to be hauled in. If you’ve seen any Buzzy cartoon, you can probably write the rest of the script from memory yourself.

Cat Carson Rides Again (Paramount/Famous, Herman and Katnip – Noveltoon, 4/4/52, Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Cat Carson (Katnip) shoots his way into town, terrorizing the mice and stealing their chuck wagon food. Herman saves the day again, by the old “above and below” basement trope, with a few added props. Carefully placing a tar barrel and a stack of pillows in the room while Katnip prepares a western omelette “smothered in mouserooms”, Herman ventures under the floorboards of the old western town, with the usual magnet. For a change, Katnip’s spurs are the object of attraction, making him easy to wheel along. First he hits the tar barrel, then the feathers (get it?). Herman continues to drag him outside below the old western sidewalks – right up to the county line, which ends in a drop off a cliff. Herman stops cold, releasing the magnet’s grip – but Katnip keeps a-rolling along, off the cliff, and into a waiting patch of cactus, where he ping-pongs from one cactus to another off into the distance, with the predictable yowls on each impact.

Woodpecker in the Rough (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker, 6/16/52, Walter Lantz, dir.) – Woody tees off in a bet match against “Bull” Dozer (a heavy who would only revisit the series once later in Wrestling Wrecks (1953) for $10.00 a hole – and Woody’s only got five cents. Bull makes 17 holes in one by a combination of cheats and lucky trick shots. His back against the wall, and Bull’s last ball already of the green at the 18th hole, Woody pulls the old switcheroo – a trick golf ball with a magnet in it in place of Bull’s real ball. (In an unusual piece of sound work, a very loud electrical hum is heard each time the magnetic rays take effect throughout the cartoon’s finale.) Unlike Terrytoons in Goony Golfers discussed above, Lantz gets it right – Dozer chooses a metal putter, not a wood. The ball, of course, won’t travel more than a few inches from his club, and repeatedly boomerangs back. Holding the ball in his hand for closer examination, Bull is whacked in the head by his club on the other side.

When the ball sticks to the club again, Bull brings the club up over his shoulders, ready to give it a fierce swing to release the ball – and only succeeds in attracting his own belt buckle and having his pants fall down. In the same manner as biting a coin to see if it’s real, Bull takes the ball between his teeth and tries to chomp on it – only to attract the putter from the ground, knocking a gaping hole through his teeth – and the ball into his stomach (seen in x-ray view against his silhouette). Woody is at the ready with Bull’s whole bag of golf clubs, which all stick to Bull’s back like the quills of a porcupine. Bull makes a run for it, ducking behind a public Civil War statute (must be a Southern course) – next to which stands a large pile of commemorative cannonballs. You guessed it – like Lulu’s watermelons, Bull makes his exit with the rolling cannonballs close behind him. Derivative, yes, but reasonably well done. It had a short life in Castle Films home movies under the title, The Goofy Golfer.

Little Anglers (Fox/Terrytoons, Terry Bears, 7/1/52 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – a bit more clever than some Terrys, though the premise is still improbable. The little bears, on a fishing trip, bring a box of nuts and bolts. They toss a handful into the water. The fish in these parts aren’t very picky what they eat, and gobble them up as they fall. (The swallowing trope once again.) Now the bears lower a magnet on a pole, and instantly catch an even dozen. Papa bear decides to try this himself, offering little bear his deluxe fishing pole in trade. Papa takes another handful of bolts and tosses them in the briny. This time we don’t see the fish above the surface, so we don’t know who’s taken the bait. Pop drops in the magnet, and we hear another klank. Reeling in, he is surprised to find just one fish – who has swallowed all the bolts, and spits them out at papa in machine-gun fashion. A smile-producing surprise.

Hypnotic Hick (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker, 9/26/53, Don Patterson, dir.) – Just a brief throwaway gag in this one, as I. Gypem, Summons Server, uses a magnet to attract Woody (wearing roller skates) into his office for a “fast buck” job proposition of serving summons on Buzz Buzzard. This would mark the only animation appearance of the magnet in 3-D. However, it’s only shown in profile, so the effect is wasted. (A pity, because other scenes of this cartoon are among the most dimensional to be created by the classic studios during the initial 1953 3-D craze.)

Hot Noon, or 12 o’ Clock For Sure (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker, 10/12/53, Paul Smith, dir.) – Three Woody magnet cartoons in a little over a year? This is getting habit forming. Another throwaway gag, as Woody and Buzz Buzzard have a brief magnet showdown. Buzz pulls out his six guns. Woody pulls out a magnet, and draws the guns from his hands. Buzz pulls out a bigger magnet and draws them back. Woody tips over a barrel of horseshoes (Lulu and Andy Panda’s pop are remembered again), which fly out of the scene and pin Buzz to the wall from head to toe.

Robin Rodenthood (Paramount/Famous, Herman and Katnip, 2/25/55, Dave Tendlar, Dir.) – Herman inherits the role of Robin Hood from Popeye (using the same Winston Sharples song sung by Popeye in Robin Hood-Winked (1948) – no waste of recyclable resources here!). The only note for this article’s purposes is tax-collector Katnip robbing mice by using a magnet – the same gag from “Buckaroo Bugs” above, without the same payoff.

Droopy Leprechaun (MGM, Droopy, 7/4/58, Michael Lah, dir.) – Widescreen Cinemascope gets the magnetic treatment in a brief sequence in an Irish castle. Droopy is mistaken for a leprechaun by Butch (or is he Spike this time?). Butch hides in a suit of armor and confronts him. Droopy runs, and misses Butch’s flying tackle – but the helmet flies off, landing on the fleeing Droopy, who runs down a corridor bedecked with a row of further armored suits (a bit obvious a setup, in this overall unsubtle cartoon). Butch gets the bright idea of pulling out a magnet to pull in Droopy – but of course, pulls in every other suit of armor as well, covering him in a heap. Droopy is pulled in too, but escapes out the drop-seat of Butch’s suit.

Salmon Loafer (Universal, Lantz, Chilly Willy, 1963, Sid Marcus, dir.) – The salmon run hasn’t started yet, so Chilly’s forced to resort to skin diving for old shoes, to which he applies a magnet to remove the nails and cook up his own “filet of sole”. When the salmon do start running, and Chilly invades St. Bernard Smedley’s cannery, he tries lowering the magnet on a string to attract the cans. Naturally, Smedley swallows the magnet. Marcus curiously uses three situations lifted from some of the very earliest cartoons on our list. First, Smedley is pursued by a meat cleaver (Donald and Pluto). Eluding it, he is attracted to a furnace (similar to the boiler in “Donald and Pluto”), from which the grating is pulled off, burning Smedley’s rear. Smedley jumps into a bucket of water, and the impact dislodges the magnet from within him. Smedley takes hold of it, stating, “This thing’s going to the bottom of the ocean”, and tosses it across the room toward an open window. In a scene mirroring Popeye’s magnetic flying leap in “Bridge Ahoy”, the magnet manages to attract en route every can of fish in the cannery, drawing the entire season’s catch into the ocean with it. The whimpering Chilly and Smedley are left to share a mutual dinner of Chilly’s pedestrian “catch” from the beginning of the cartoon.

You may be wondering at this point how I’ve passed someone in this chronology. Chuck Jones was in a class by himself. If anyone singlehandedly appears to have impressed on the public the concept of prop comedy in cartoons, it was Chuck in the ever-popular “Road Runner” series for Warner. In an informal survey of my co-workers (distinctly lacking in depth of animation knowledge) as to the origins of cartoon magnet gags, I received almost uniform responses of belief that Chuck Jones had created them in the Road Runner cartoons. Certainly, Chuck was probably more responsible than anyone for making them a cliche – and a later part of Marvin Acme’s toon props in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, though he never animated a frame in that film – but as we have seen, he was certainly not the creator. In fact, Chuck didn’t instantly integrate the magnet into his series. His first use of it by Wile E. Coyote didn’t come until the fourth installment of the series, Zipping Along (Warner, 9/19/53), in which the Coyote first mixes bird seed with “Ace Steel Shot” (later referred to as Acme iron pellets). The Road Runner engages in one of those careless and lightning-fast gorging sessions on the free lunch, then takes off. Coyote leaps out of the rocks, holding a giant magnet. From nowhere, it attracts an unexpected quarry – a giant metal drum, marked “TNT’, also including a lit fuse. Wile E. barely has time to make eye-contact with the audience as it goes off – leaving only the magnet tied in a pretzel-knot, and a coyote-shaped hole in the rock cliff behind them.

To catalogue all uses of the magnet/steel shot premise and other variants in Chuck’s series (and in later Rudy Larriva episodes) would be unduly time-consuming and beyond the intentions of this article. Instead, special mentions will be made of two well-timed uses by Chuck of more up-to-date weaponry, without the need for bird seed. The first occurred in Cat Feud (Warner, 12/20/58), an installment in the Marc Anthony and Pussyfoot dog and cat mini-series. A somewhat re-designed Claude Cat has been making things tough for Pussyfoot at a construction yard, and stealing his food. Bulldog Marc Anthony prevents Claude’s use of a sledge hammer on poor Pussyfoot by aiming an industrial electro-magnet over his head. As he throws the switch, Claude is drawn skyward by the hammer, sticking to the magnet. The handle comes loose from the hammerhead, sending Claude falling earthward, landing on a beam. Marc Anthony turns the power off, releasing the hammerhead to fall on Claude.

Claude avoids the blow by grabbing a construction hard-hat, so the falling weight bounces off. But Marc Anthony activates the magnet again, drawing Claude up by the hard-hat. Marc Anthony toys with him, intermittently cutting and reactivating the power so that Claude is bounced up and down against the magnet. Anthony is briefly interrupted by the need to rescue Pussyfoot from walking off a girder. Meanwhile, Claude lets loose of the hard-hat and somehow manages to lower himself down a beam to the ground. Anthony returns to the magnet controls, using another lever to re-maneuver the magnet over Claude. Claude runs, but stumbles over and gets all four paws trapped in a metal bucket. The magnet reaches its target, and hauls Claude upwards in the bucket. The hard hat is still stuck to the magnet’s underside, and Claude is tightly pinned between the bucket and the hard hat. The scene transfers to late in the evening, with Claude still stuck in his predicament, destined to spend the night there – and maybe forever. (Jones would revisit these electromagnet ideas in the producer’s chair, with Abe Levitow as director, for MGM in 1966 with Tom & Jerry’s Guided Mouse-ille, or Science on a Wet Afternoon – with Jerry repeatedly raising and dropping the head of a sledge hammer onto Tom, producing bigger and bigger lumps.)

Claude avoids the blow by grabbing a construction hard-hat, so the falling weight bounces off. But Marc Anthony activates the magnet again, drawing Claude up by the hard-hat. Marc Anthony toys with him, intermittently cutting and reactivating the power so that Claude is bounced up and down against the magnet. Anthony is briefly interrupted by the need to rescue Pussyfoot from walking off a girder. Meanwhile, Claude lets loose of the hard-hat and somehow manages to lower himself down a beam to the ground. Anthony returns to the magnet controls, using another lever to re-maneuver the magnet over Claude. Claude runs, but stumbles over and gets all four paws trapped in a metal bucket. The magnet reaches its target, and hauls Claude upwards in the bucket. The hard hat is still stuck to the magnet’s underside, and Claude is tightly pinned between the bucket and the hard hat. The scene transfers to late in the evening, with Claude still stuck in his predicament, destined to spend the night there – and maybe forever. (Jones would revisit these electromagnet ideas in the producer’s chair, with Abe Levitow as director, for MGM in 1966 with Tom & Jerry’s Guided Mouse-ille, or Science on a Wet Afternoon – with Jerry repeatedly raising and dropping the head of a sledge hammer onto Tom, producing bigger and bigger lumps.)

Chuck’s second tour-de-force with the electromagnet came in a pair-up between Wile E. Coyote (in talking mode) and Bugs Bunny, in Compressed Hare (Warner, 7/29/61, Maurice Noble, co-director) . Wile E. doesn’t mess around when he packs a secret weapon – the packing crate for the contraption announces the magnet’s capacity as 10 billion volts! Notably, this machine looks nothing like the more realistic one from Cat Feud, but is shaped at the forefront like a giant version of our standard red horseshoe. Add one “Acme Iron Carrot – fool your friends”, and the trap is set. Believing that Bugs has taken he bait, Wile E. activates the magnet, waiting in front of it with a catcher’s mitt for his prey. At his rabbit hole, Bugs releases the iron carrot he didn’t eat. At the same time, Bugs’ mailbox flies off its pole toward Wile E.’s cave. Wile E. sees the carrot coming minus Bugs – and ducks out of its way – but comes up again in time to intersect the path of Bugs’ mailbox, landing on his snout. A flat iron, frying pan, trash can, and sledge hammer rapidly appear in succession out of Bugs’ hole. Coyote ducks these successively, but makes contact withe Bugs’ bed and stove rolling in his cave door. Bugs comments to the audience, “Well, that ought to set him up in housekeeping.”

But the best is yet to come. In a sequence to rival (and undoubtedly inspired by) Tex Avery’s finale to Bad Luck Blackie (MGM, 1949), every metal object in the county flies over Bugs’s hole headed to Wile E.’s cave – stop signs, pot-bellied stoves, barbed wire, an old jalopy, a bathtub, a light pole, a ceiling fan, a shopping cart, a water tank, a weather vane, a tractor, lamps, clocks, a greyhound bus, assorted tools and tin cans, to name a few. Bugs can only watch in awe as an ocean liner slides across land past his hole – followed by the Eiffel Tower! Various satellites and missiles begin raining from the sky. And as a topper to end all toppers, an ignited Atlas rocket lodges its nose into the entrance to Wile E.’s cave, and explodes. As bugs’s eyes look skyward, he confides in us, “One thing’s for sure…We’re the first country to get a coyote into orbit.” This one must have had the audiences rolling in the aisles.

A final honorable mention again goes to Fleischer for one more magnet cartoon not on the beaten path of our trail – The Magnetic Telescope (Paramount, Superman, 4/24/42). Not at all played for laughs, this one’s a genuine sci-fi thriller. A not-so-mad scientist has developed an electric-powered giant magnetic ray attachment to his astronomical telescope – to pull comets from the sky for closer examination, then repel them back into space by reversing the polarity (the only magnet cartoon I know of to explore the repulsion principle). His first attempt, however, goes unfortunately awry, drawing a comet into the streets of the big city. Determined to prevent a repeat performance, the police attempt to shut the operation down. But the scientist is equally determined to give the thing one more try – and lowers some barriers to prevent the cops from gaining access to the control room. Not to be thwarted, the police attack the power generator, shutting down the scientist’s electricity – not realizing he’s already started the tractor beam, and set a comet on a collision course with earth. (It would have taken a 50’s sci-fi director at least a half hour to set up this scenario in live action, yet Fleischer accomplishes it in about three minutes.) Of course, Lois is on the scene – and it’s another job for Superman. The animation, as with nearly all Fleischer Supermans, is splendid in color choices and detail. The scenes where Superman, in order to restore the power, uses himself as an electrical conductor, with the voltage racing through him, are “marvel”ous (no pun intended, DC). The repulsion mechanism is finally engaged, and the scientist’s work vindicated.

Thus ends the first of our long, long trails a-winding. Well, not really. I’m sure there may be a few I’ve missed from the good-old-days (though probably not very influential, if they’ve slipped my memory). Feel free to contribute your comments if you remember more. There were also, of course, countless TV cartoons that followed. Magnetic rays would play space-age roles as secret weapons in Hanna-Barbera’s Ruff and Reddy flight to Muni-Mula. The Master Cylinder would capture Poindexter’s space ship with a horseshoe magnet in Felix the Cat. (Was this bought at a Paramount army surplus store from “The Magnetic Telescope”?) Blastoff Buzzard would mimic Wile E. Coyote in Hanna-Barbera’s “C.B. Bears” (see “The Egg and Aye Aye Aye”). Etc. The tropes will probably never die – always good for a quick, if not always creative, laugh.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles, a summary of “The Cat and the Magnet” appears in the Nov. 1, 1924 edition of Moving Picture World:

“The Cat and the Magnet”

(Pathe—Cartoon—One Reel)

Cartoonist Paul Terry supplies his cat with a magnet with which that animal proceeds to magnetize mice and their little autos into a hollow tree trunk. There the cat resells the cars. The idea is not only original but is clever from the standpoint of laughs.—T.W.

One more Chuck Jones magnet gag of note is on the TV classic How the Grinch Stole Christmas, where the Grinch uses a magnet to remove the nails holding stockings to the fireplace, then catching the falling stockings on his bag.

And as with many cartoon tropes, the red horseshoe magnet gets a shout-out on Who Framed Roger Rabbit, as Eddie Valiant uses one to fight against Judge Doom in the climax. In a neat touch, the magnetic rays have hands to grasp the object being attracted, in this case Doom’s cane sword (and, accidentally, a steel drum that briefly traps Eddie between it and the magnet).

Although the award goes to Slappy Squirrel for most violent character during the first season of Animaniacs, the hosts, Yakko, Wakko, and Dot have a laundry list of “hurt gags” you should cover that Looney Tunes were stereotyped for during the first season of Animaniacs (no wonder we were locked in that water tower!):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2pLuom1N3H0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FXXhZ2Rz2dQ

Wow! This is gonna be an excellent series. Great job, Charles.

The Shakespearean hound in “A Ham in a Role” is quoting the very end of Richard III: Act V, Scene 3, where Richard III is speaking:

A thousand hearts are great within my bosom.

Advance our standards, set upon our foes.

Our ancient word of courage, fair Saint George,

Inspire us with the spleen of fiery dragons!

Upon them! Victory sits on our helms.

The mention of Snub Pollard’s short IT’S A GIFT (23) as a possible inspiration for the use of magnets as gag material in animation brings to mind that a year earlier Buster Keaton did battle with a giant magnet in THE BLACKSMITH (22). This magnet hung outside the door of the barn which houses the blacksmith and both Keaton and his nemesis, Joe Roberts, take turns losing their iron hammers to the gravitational pull of the magnet. When the sheriff arrives after a typical melee, his gun and badge are also lost upwards to the mysterious pull. Eventually, Keaton discovers what is causing all of the trouble and he climbs up to dislodge all of the lost items only to bring the entire giant magnet crashing down to earth upon poor Joe’s being.

How about an example of a latter-day magnet gag from a studio not mentioned above – Never Bug an Ant (1969), an “Ant and the Aardvark” short from DePatie-Freleng Enterprises.

Fingers crossed for potential lengthy dissertations on bullfight and symphony conductor cartoons (Every studio did ’em!)

There’s another magnet gag in Friz Freleng’s “Meatless Flyday” (January, 1944) that has a very curious footnote. In that gag, the spider (voiced by Cy Kendall) coats buckshot with Kandy Kolor — and if you look at the label, the manufacturer is the notorious I.G. Farben, the German company that would later have executives be indicted for war crimes. (i.G. Farben was a dye company, at its root — hence, candy colour.) The spider uses a magnet, which attracts the contents of a cutlery storage area, almost causing him to lose his toes. Another point of interest: a rare usage of Raymond Scott’s “Siberian Sleighride” during the gag — not one of the Scott songs used very often in WB cartoons.

What, you’re really going to slag a Terrytoon for violating the laws of both physics and golf? As Heckle would say. “Take it easy, pal!”.

TV Tropes is gonna love this one!

I had forgotten how magnificent a cartoon “Donald and Pluto” is – just perfect from start to finish. And the kitchen scenes were clearly an inspiration for “Somethin’s Cookin'”, the opening cartoon in “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.”

There’s a gagnet mag — excuse me, magnet gag — in Frank Tashlin’s 1937 Porky Pig cartoon “Porky’s Road Race”, which is notable for its caricatures of Hollywood stars (Laurel and Hardy, W. C.Fields, Clark Gable, etc.) Boris Karloff, dressed as Frankenstein, tries to sabotage the race by dumping a box of tacks onto the roadway. Charles Laughton, dressed as Captain Bligh and driving a race car called “Floating Power”, picks up the tacks using a horseshoe magnet on the end of a fishing line.

“The Tortoise Wins Again” (minor correction: John Foster did the story, but Connie Rasinski directed) is a remake of “The Ice Carnival” (Terrytoons/Fox, 22/8/41 — Eddie Donnelly, dir.). The older cartoon introduces the horseshoe magnet earlier in the proceedings, when the young tortoise uses it to retrieve a skate that has fallen through a hole in the ice, but the denouement is exactly the same. These cartoons teach us that “slow and steady” doesn’t win the race after all — cheating does!