Author’s Note: Just last week, I spent a week in California around the Burbank/Glendale area, meeting a lot of people and taking in as many sights as I could. I’d like to extend my thanks to the wonderful historians who took the time to speak with me, even if some interactions were relatively brief.

Virgil Ross with assistant Warren Batchelder, circa 1945

Today’s animation profile goes into an overview of one of the greats, Virgil Ross!

Virgil Walter Ross was born in Watertown, New York on August 8th, 1907. At the age of 10, Ross’ family moved to Michigan, where they resided in the Detroit suburb of Highland Park. Around 1918, they relocated to California in Long Beach, but moved further up north to Compton by the late 1920s. While in high school, Ross attended a cartooning class, which inspired a professional career after graduation. In an office on Figueroa in downtown Los Angeles, he worked as a commercial artist drawing show cards and titles for silent films. Later, Ross was given a recommendation to take his portfolio to Walt Disney’s studio. In an interview with John Province, Ross recalled, “So I went to the Disney studio on Hyperion, and they said they would be in touch. While I was out, I figured I’d try someone else, so I looked up [Charles] Mintz studios in the telephone book and went over.”

In 1930, producer Ben Harrison hired Ross at Mintz as an in-betweener on the Krazy Kat cartoons. A young Chuck Jones worked at Mintz for a brief period but switched to Ub Iwerks’ studio. He contacted Ross with an offer to work at Iwerks, where he moved around September 1931. His time at Iwerks was brief; he was laid off shortly after Christmas, along with other artists. Without a job in the height of the Great Depression, Ross soon landed at Walter Lantz’s studio in May 1933, where he worked as an assistant to Tex Avery, one of their top animators/gag men. He was promoted to full animator by 1935, working on Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons such as Do a Good Deed, Springtime Serenade and Towne Hall Follies.

Around 1935, Avery was put under contract with producer Leon Schlesinger as a director on the cartoons distributed by Warner Bros. Ross (and fellow animator Sid Sutherland) followed him, working in the “Termite Terrace” building with Chuck Jones and Bob Clampett. Evidently, Bob McKimson gave Ross further training and taught him to draw a center line around the character’s head in his rough animation. “The line would show about where the center of the body and the head were. Then you could round the head off and keep both eyes in perspective. Another thing McKimson taught me was to keep the pupil touching either side of the eye, because if it’s in the middle, the character looks like he’s staring wildly ahead.” After Avery left the studio in the summer of 1941, Ross was switched to Bob Clampett’s unit. When Avery landed a directorial position at MGM later that fall, he wanted to hire Ross as one of his animators but he refused. It can be assumed since he married studio inker Frances Ewing in 1940, Ross decided to settle at Warners. (The two remained together for almost 55 years.)

Though he worked with Clampett during his peak period at Warners on such titles as The Hep Cat, Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid and Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs, Ross confessed that he and Clampett “didn’t hit it off too well. I didn’t seem to have what he wanted most of the time.” After about a year, Ross moved to Friz Freleng’s unit, with Warren Batchelder as his long-time assistant by 1945. He described his working methods with Freleng: “We used to make a pencil rough of the entire picture. Then Friz would bring us in and decide what needed to be changed. We were assigned just individual scenes, with no idea what had happened before or what was happening after. It was pretty hard to judge them that way, because in order to analyze them properly, you really should know what it’s going to be hooked up with. If they had run the scenes connected with all of the others, I doubt we would have had to make so many changes, but that’s how we did it for years.”

Ross continued animating for Freleng until summer 1953, when the studio shut down its animation department to see if the 3-D trend would affect its output. One of his true passions was playing the piano, as many artists who have met Ross fondly remembered. (Rhapsody Rabbit [1946] and Hyde and Hare [1955] are among a few examples of his musical abilities, assuring the correct piano keys were struck as Bugs Bunny performed in both cartoons.) “It was about this subject his eyes lit up,” said Greg Duffell. “He also enjoyed dancing. He was upset about being overlooked from being selected by Friz to do the dance sequences in the cartoons he directed [which ultimately went to Gerry Chiniquy.]” With this talent, he found work playing the piano in nightclubs while the studio ceased its operations. He came back to Warners as an animator for Freleng, while also moonlighting on commercials for Paul Fennell’s studio in the mid-1950s; two such examples are plugs for Schmidt’s Beer and Oreo cookies.

By the early 1960s, the Warners animation department cut back on their theatrical cartoons, kept afloat by television production with their half-hour program The Bugs Bunny Show along with various commercials. It seemed to reason that a few staffers, including Ross, went to other studios when Warners went through intermittent phases of downtime. Variety announced in August 1960 that Ross was hired, among several others, at Animation Associates to work on Q.T. Hush. Around 1961, Ross freelanced at Hanna-Barbera as an animator (credited on the Augie Doggie cartoon Let’s Duck Out), while he also worked for Freleng at Warners before leaving indefinitely in 1962.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Ross animated for several studios including Hanna-Barbera, Ed Graham (Linus the Lion-Hearted), Format Films/Warner Bros-Seven Arts (the later Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies theatricals), Filmation, DePatie-Freleng, Walter Lantz and Ralph Bakshi (Fritz the Cat). While at Filmation in the late 1960s, Mark Kausler recalled to the late Tee Bosustow that Ross was helpful to the young in-betweener. He felt pressured over making his footage quota of 100 feet a week. “Virgil was wonderful to me because I was so worried about my footage,” Mark stated. “He said ‘Don’t worry about it, kid. Don’t worry about it, just do the best you can. If you can’t make it on this job, you’ll make it on the next one.’ He was so nice to me and so calming.” According to Greg Duffell, when Ross was reunited with Bob McKimson at DePatie-Freleng, he still relied on McKimson to improve his drawings on the Pink Panther cartoons. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, he animated for Friz Freleng, Chuck Jones Enterprises, Warner Bros. Television, Filmation, DePatie-Freleng/Marvel and Hanna-Barbera.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Ross animated for several studios including Hanna-Barbera, Ed Graham (Linus the Lion-Hearted), Format Films/Warner Bros-Seven Arts (the later Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies theatricals), Filmation, DePatie-Freleng, Walter Lantz and Ralph Bakshi (Fritz the Cat). While at Filmation in the late 1960s, Mark Kausler recalled to the late Tee Bosustow that Ross was helpful to the young in-betweener. He felt pressured over making his footage quota of 100 feet a week. “Virgil was wonderful to me because I was so worried about my footage,” Mark stated. “He said ‘Don’t worry about it, kid. Don’t worry about it, just do the best you can. If you can’t make it on this job, you’ll make it on the next one.’ He was so nice to me and so calming.” According to Greg Duffell, when Ross was reunited with Bob McKimson at DePatie-Freleng, he still relied on McKimson to improve his drawings on the Pink Panther cartoons. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, he animated for Friz Freleng, Chuck Jones Enterprises, Warner Bros. Television, Filmation, DePatie-Freleng/Marvel and Hanna-Barbera.

In the early 1980s, Ross freelanced at DimenMark International (The Great Bear Scare) and Rick Reinert Productions, the latter studio being a short distance from his home at the Hollywood Hills. Dave Bennett, who worked as an animator at the studio recalled: “We somehow heard he was looking for work and invited him to our studio…Even though he was 75 at the time, he was spritely and energetic. He was an incredibly sweet, soft-spoken, humble and modest gentleman. He was so respectful and eager to please that it almost seemed like he was trying out for his first job in animation, rather than what would be the coda to a distinguished career!” He worked on a few projects for the new EPCOT attraction at Disney World featuring Donald Duck. Dave Bennett continues: “[Ross] had such trepidation about animating Donald that he must have stayed up all night filling about six sheets of animation paper with his own poses and expressions of Donald, and we both joked about how much the character he had drawn looked like the illegitimate offspring of Daffy and Donald!” Ross also worked on Winnie the Pooh and a Day for Eeyore (1983), which was outsourced to Reinert.

In 1984, Ross’ career in animation was recognized when he received the Motion Pictures Screen Cartoonists Award. Around 1987, Greg Duffell contacted him about animating a “Shreddies” cereal commercial for his company Lightbox Studios based in Toronto. “The ad agency had changed and we knew that they did not want to use us anymore,” said Greg. “I thought it would be ironic to have a brilliant and famous animator perform this task, something the agency would never know, let alone recognize or appreciate.“ Shortly after, Ross was honored with the Winsor McCay Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1988. One of his final projects as an animator was on the Nickelodeon television special Christmas in Tattertown, produced by Ralph Bakshi. According to Tom Minton, who co-wrote the special, Ross appeared only momentarily at Bakshi’s studio.

Virgil Ross, 1992 (courtesy of John Province)

In the 1990s, he produced a series of limited-edition cels to be displayed in animation art galleries and Warner Bros.-themed stores. At one peculiar gallery showing in Burbank during that period, animator Dan Haskett shared that a clerk informed an acquaintance of Dan’s that the art “was the work of the late Virgil Ross,” though Ross was alive at the time. Dan’s friend “went and got Virgil and brought him back to the store… and went back to the same clerk and said, ‘Would you explain to me about this work once again, please, for my Grandpa here?’” After the clerk’s spiel, Ross exclaimed, “Well, I’m Virgil Ross and I’m not dead, and I don’t appreciate this!” and pulled the sign from the wall that mentioned the late Virgil Ross. He passed away on May 23, 1996 in Los Angeles at the age of 88. According to Tom Minton, skillful piano music played over the chapel sound system at Ross’ funeral service. Chuck Jones was in attendance and while he delivered his speech, he casually mentioned, “The piano music you’re listening to was played by Virgil Ross.”

In a recent visit with Mike Kazaleh, he stated simply about Virgil Ross’ animation: “His style never changed.” Ross’ work sustained an elegance and subtlety in his character animation throughout his career. Besides the solidity of his drawing, one of the nuances that stands out are how characters often use their hands to complement dialogue. Watch this reel below (from ‘ibcf’) and perhaps it will help to understand, though all of the clips are from Warners cartoons:

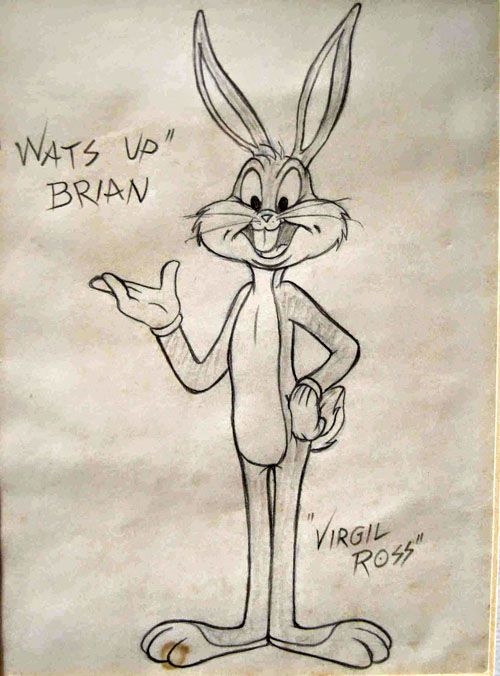

Virgil Ross gifted drawing to Brian Mitchell, circa 1979-600

(Thanks to Frank Young, Joe Campana, Harry McCracken, Yowp, Greg Duffell, Tom Minton, Dan Haskett, Mike Kazaleh, Tom Klein, Thad Komorowski, Dave Bennett and Jerry Beck for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Virgil Ross is one of my all-time favorite animators. His distinctive style is easy to pick out (love those cheek dimples!), and lightens up pretty much any cartoon, even those with limited animation.

An example: He worked on the TV special “Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy in the Pumpkin Who Couldn’t Smile”, which is hardly one of the great pieces of animation history, but his work in the first few minutes is as charming as ever. Same goes for his all-too brief contribution to the aforementioned “Christmas in Tattertown” special- most of the special is sloppily animated outsourced stuff, but then comes Ross’s animation in the last act (“Holy smoke, it must be Santa!”) and the quality immediately improves. Too bad it’s over as quickly as it starts.

Of course, it does no favors to solely call attention to his work on later cartoons, because his work at Warner Bros. was always reliable and top notch. In fact, his absence in a few of those mid-50s shorts (produced while the studio was shut down) is noticeable, and it was a relief that he returned. I always wonder how much better “This is a Life?” would’ve been had he animated for it, because his graceful way of animating talking would’ve been perfect for that dialogue-heavy short.

What a great article about one of my favorite WB animators – thank you!!

Virgil Ross married Frances Ewing on January 9th 1940.

Noted, and will be corrected soon!

I too remember having clueless encounters with those “clueless ‘animation’ art galleries” that popped up in the 90s.

Early this century, I recall one encounter even was a Ross print that had Egghead on it that the guy insisted was Wimpy.

I never had the energy to argue, they were so adamant about their ignorance.

Thanks for the article, Ross is one of my favorites!

Although the cartoon itself isn’t particularly notable, 1953’s “Hare Trimmed” has what is perhaps my favorite piece of animation by Ross, of Bugs in character as a foppish gentleman walking out of the scene:

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2ofa0f (at 02:59)

There is such character in that walk and body language, and the perspective shift as he turns is impeccable. There’s even a windup!

It’s a little depressing to watch the Woody appearance at the Academy Awards; Virgil’s peak was far behind him, sadly.

“Although the cartoon itself isn’t particularly notable”

Not particularly notable? “Hare Trimmed” is one of Friz’s best! Although like any great cartoon, it does veer CLOSE to being overrated simply from overexposure.

There are a couple rough animation reels (i.e. not cleaned up or colored yet) from that cartoon on YouTube if you search for them.

I was probably unconsciously holding lesser and redundant efforts like “For the Love of Money” against it. 🙂

This article is wonderful. Filled with info, I’m in awe being a bit of a cartoon nut.

The music, the movement, the humor, and the short nuggets of enjoyment.

Thank you.

Virgil, I found out, was my great grandpa’s brother

It should be noted that Virgil Ross had a young assistant named Lee Holley circa 1957-1959. Lee went on to assist Hank Ketcham on Dennis the Menace the Menace, as well as produce his own syndicated comic strip “Ponytail” that ran for nearly 25 years. Lee always spoke very highly of Virgil and was forever grateful for being taken under his wing. The photo of Virgil with his awards was actually taken by me during one of my many visits to his home. I bought the Bugs doll for the photo and gave it to him afterwards. Very nice man and a truly fine animator.

Dear Devon,

Thanks for writing this very nice biography. I found your page while preparing the WikiTree profiles of Fred C. Ewing’s family. It led me to his daughter Frances Emily Ewing, which led me to her husband Virgil Ross, and then to Wikipedia and your page. You let me know how they met and that she was an inker at Warner Bros. Thank you for that.

Here are my three questions:

• Do you know when Frances was an inker?

• Can you tell me more about photo of Virgil and Frances dancing?

• May I post the photo of Virgil and Frances dancing on their WikiTree profiles? https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Ewing-4530

Thanks for any information you can provide.

Sincerely, Mark Griep