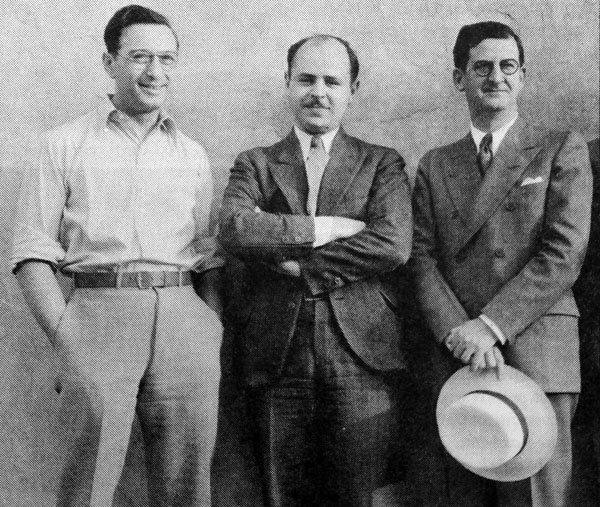

Composer Joe DeNat, artist Art Davis, and producer Charles Mintz

We’ve saved the best for last—an overview of the vast career of animator/director Arthur “Art” Davis, a favorite among many…

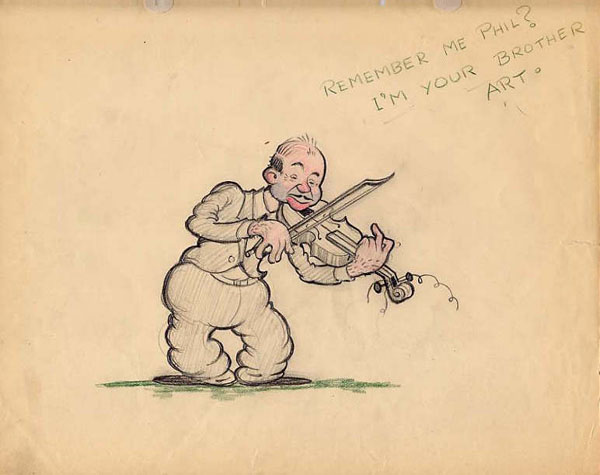

Born on June 14, 1905 in Yonkers, New York as Arthur Davidavitch to Hungarian parents, Art Davis started his career in animation in the summer of 1918 as an office boy at the Barré-Bowers studio, located in the Fordham section of the Bronx. His eldest brother, Mannie Davis, animated on their Mutt and Jeff cartoons. According to the July 1947 issue of Warners Club News, Davis worked as an apprentice diamond cutter after he graduated from Yonkers High School. A subsequent issue of the newsletter mentioned a job as a laundry truck driver routed around New York City, though it’s unclear when this occurred. He continued to work on the Mutt and Jeff cartoons, now released by the Jefferson Film Corporation. Davis was promoted to an eraser—he removed the pencil lines on the animator’s drawings, which were inked on paper. By January 1921, mentioned in a story from The Yonkers Statesman, Davis won first place in a “cartoon contest” for the Yonkers Chamber of Commerce.

Born on June 14, 1905 in Yonkers, New York as Arthur Davidavitch to Hungarian parents, Art Davis started his career in animation in the summer of 1918 as an office boy at the Barré-Bowers studio, located in the Fordham section of the Bronx. His eldest brother, Mannie Davis, animated on their Mutt and Jeff cartoons. According to the July 1947 issue of Warners Club News, Davis worked as an apprentice diamond cutter after he graduated from Yonkers High School. A subsequent issue of the newsletter mentioned a job as a laundry truck driver routed around New York City, though it’s unclear when this occurred. He continued to work on the Mutt and Jeff cartoons, now released by the Jefferson Film Corporation. Davis was promoted to an eraser—he removed the pencil lines on the animator’s drawings, which were inked on paper. By January 1921, mentioned in a story from The Yonkers Statesman, Davis won first place in a “cartoon contest” for the Yonkers Chamber of Commerce.

Around 1922, Davis moved to Max Fleischer’s studio, where he became an assistant to chief animator Dick Huemer on the Out of the Inkwell series. As his assistant, Davis became the first true in-betweener in American animation. He drew every intervening pose within Huemer’s key drawings to smooth the action. Davis’ new position was intended to increase productivity from Huemer, given his high salary at the studio. This continued on an intermittent basis until 1926. For the Song Cartunes, Davis also moved the “bouncing ball,” dressed in all black, he moved the cut-out white circle on a black stick as each lyric appeared on screen. Davis recalled that he enjoyed this task since he did not have to remain at his desk. Based on another mention in The Yonkers Statesman, Davis devoted much of his time drawing novelty place cards by February 1927. He met female inker Rae Kessler at Fleischer’s studio, whom he married in 1928. (The two remained together until her death in 1978.)

Davis moved to Charles Mintz’s studio as an assistant animator on the Krazy Kat cartoons produced by former Fleischer artists Ben Harrison and Manny Gould. By 1929, he became a full-fledged animator. As Charlie Judkins surmised, his animation in the first season of Krazy Kat sound cartoons (1929 to 1930) appears relatively loose and fluid yet shows the influence of Dick Huemer in its emphasis on detailed facial expressions. In Farm Relief (1929), Davis animated an extended sequence of a drunken rendition of “Down by the Old Mill Stream”. He befriended animator Friz Freleng, who worked at Mintz for a brief stint away from the West Coast. In later years, Freleng and Shamus Culhane (an inker during that time) felt Davis’ animation was more advanced than the other artists.

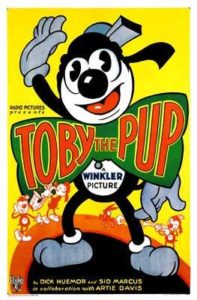

Sometime in 1929, Davis received a telegram from Walt Disney who invited him to join his studio in the West Coast, but he refused. In February 1930, Davis went along with the Mintz staff when the decision came to relocate their operations in California, as they traveled in a private railroad car. His older brother Mannie Davis remained in New York as an animator at the Van Beuren Corporation. A short time later, Davis worked with Dick Huemer again, along with Sid Marcus, on a series with Toby the Pup, released by RKO Radio Pictures, which only lasted for 12 cartoons from 1930 to 1931. After RKO and Mintz discontinued the Toby series, the three animators grouped together on a series of cartoons featuring a little boy character named Scrappy.

Sometime in 1929, Davis received a telegram from Walt Disney who invited him to join his studio in the West Coast, but he refused. In February 1930, Davis went along with the Mintz staff when the decision came to relocate their operations in California, as they traveled in a private railroad car. His older brother Mannie Davis remained in New York as an animator at the Van Beuren Corporation. A short time later, Davis worked with Dick Huemer again, along with Sid Marcus, on a series with Toby the Pup, released by RKO Radio Pictures, which only lasted for 12 cartoons from 1930 to 1931. After RKO and Mintz discontinued the Toby series, the three animators grouped together on a series of cartoons featuring a little boy character named Scrappy.

Starting with the Scrappy cartoons, the main title credits only story and animation. The person credited on “story” was the de facto director, which indicated a certain artist performed both writing and directorial duties, while they also served as an animator. Each of the men split their animation into sections. Sid Marcus recalled Davis’ work in an interview as “smooth.” Huemer directed each of the Scrappy entries released from 1931 to early 1933. He then left Mintz for Walt Disney’s studio. Sid Marcus took over the directorial spot, with Davis as his main animator (and a few uncredited assistant artists). A year later, Davis began directing his own cartoons at Mintz, with the Color Rhapsody Babes at Sea (1934).

Throughout the 1930s, he wrote, directed, animated and drew his own layouts on several Color Rhapsodies and Scrappy cartoons, while he animated on Marcus’ films. (Marcus and Davis worked on at least one Krazy Kat, The Bird Stuffer, released in 1936.) In his films, he displayed eccentric filmmaking techniques, particularly transitional wipes and montage sequences. Davis’ cartoons for Mintz often invite clever premises and variants. In Let’s Ring Doorbells (1935) Scrappy and his brother Oopy’s game of “ding-dong ditch” imprisons them in a dark house of doorbells; the Color Rhapsody Let’s Go (1937) is a Depression-era retelling of “The Grasshopper and the Ants” and The Clock Goes Round and Round (1937) experiments with optical effects using live-action stock footage and photographs, as the world comes to a standstill when Scrappy stops all clocks. One of Davis’ Color Rhapsodies, The Little Match Girl (1937), was nominated for an Academy Award—only one of two films at Mintz to hold this distinction.

After Charles Mintz passed away in 1939, the films were released under Columbia’s Screen Gems banner. Studio manager Jimmy Bronis assumed control, and Mintz’s brother-in-law George Winkler soon succeeded him. During the early 1940s, the studio underwent a large organizational upheaval when their distributor noticed the quality of the Screen Gems product, as Davis recalled to Michael Mallory: “Columbia was unhappy with the pictures coming out. There was no overall head at the studio. Everyone was working on their own, hit or miss.” In March 1941, Frank Tashlin joined Screen Gems as a writer, but soon became production supervisor of the films. Winkler was dismissed as general manager and replaced by Ben Schwalb, who produced the live-action shorts for Columbia.

After Charles Mintz passed away in 1939, the films were released under Columbia’s Screen Gems banner. Studio manager Jimmy Bronis assumed control, and Mintz’s brother-in-law George Winkler soon succeeded him. During the early 1940s, the studio underwent a large organizational upheaval when their distributor noticed the quality of the Screen Gems product, as Davis recalled to Michael Mallory: “Columbia was unhappy with the pictures coming out. There was no overall head at the studio. Everyone was working on their own, hit or miss.” In March 1941, Frank Tashlin joined Screen Gems as a writer, but soon became production supervisor of the films. Winkler was dismissed as general manager and replaced by Ben Schwalb, who produced the live-action shorts for Columbia.

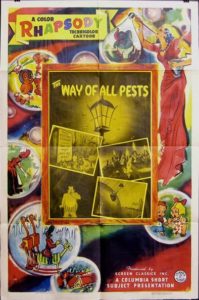

Davis managed to direct at least one cartoon for the Phantasies (The Way of All Pests, which features a self-caricature of its director) and Fables (The Great Cheese Mystery, with story by Frank Tashlin) that took up much of Screen Gems’ production schedule. By the end of 1941, Davis was fired and replaced at a smaller salary by Bob Wickersham. Davis managed a liquor store for three months before he moved to Warner Bros. as an animator for director Norm McCabe by summer 1942. Tashlin returned to the studio by September after being terminated from Screen Gems, and Davis moved to his unit when McCabe left for the Army. Though Davis was fired under Tashlin’s supervisory position at Screen Gems, there was no animosity between them. Tashlin departed by August 1944, and Davis moved to the new directorial unit headed by Bob McKimson. By this time, producer Leon Schlesinger sold the animation department to Warner Bros. and was succeeded by Eddie Selzer.

In May 1945, Bob Clampett left the studio and Davis was given his own directorial unit, assumedly based on his experience at Screen Gems. He left a scene for McKimson’s One Meat Brawl (released 1947) unfinished, which Rod Scribner completed, though Davis himself had two other cartoons to finish, originally slated for Clampett— Bacall to Arms (released 1946) and The Goofy Gophers (released 1947). Clampett supervised the dialogue track for Goofy Gophers, but as Davis said to Michael Mallory: “It was up to me to use it or not use it. I listened to the soundtrack and the voices were kind of cute, so I thought, ‘Why redo it?’”

Throughout his directorial stint at Warners, Davis’ unit fluctuated significantly in terms of story men, animators and layout artists. The same month Davis gained his unit, George Hill and Hubie Karp (the latter uncredited) were assigned to Davis as story men. Tom McKimson, formerly in Clampett’s unit, drew layouts and model sheets for Davis before he left the studio to work in comic books full-time at Western Publishing. Don Smith, a former Disney artist, took over layout duties for the remainder of Davis’ cartoons. As different animators shifted to various directors from film to film, his animation crew solidified by the summer of 1946. These animators included Bill Melendez, Don Williams, Basil Davidovich and Emery Hawkins.

Throughout his directorial stint at Warners, Davis’ unit fluctuated significantly in terms of story men, animators and layout artists. The same month Davis gained his unit, George Hill and Hubie Karp (the latter uncredited) were assigned to Davis as story men. Tom McKimson, formerly in Clampett’s unit, drew layouts and model sheets for Davis before he left the studio to work in comic books full-time at Western Publishing. Don Smith, a former Disney artist, took over layout duties for the remainder of Davis’ cartoons. As different animators shifted to various directors from film to film, his animation crew solidified by the summer of 1946. These animators included Bill Melendez, Don Williams, Basil Davidovich and Emery Hawkins.

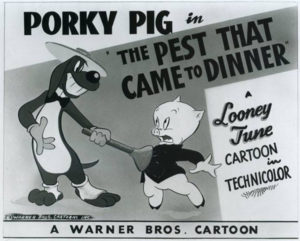

Though Davis claimed to have worked on stories for his cartoons at Warners, some accounts claimed he was insecure about his story men, putting more focus and energy towards his animators. Like Davis, Hill had experience in various New York animation studios, such as Bill Nolan’s Krazy Kat studio in the 1920s and Max Fleischer in the 1930s. In an interview with Mike Barrier, Lloyd Turner said Hill was “too literate for that job. He was very well read, he had a wonderful vocabulary.” Evidently, Hill was unhappy with his position as a story man for Davis, who was unreceptive towards Hill’s storyboards. “He would sneak out and go across the street to a little bar called the Ski Room,” Turner continued. “George would sneak over there and have drinks.” One day, Hill stormed off the studio lot after an unsuccessful story pitch and returned in an inebriated state, altercating with Eddie Selzer and the studio guard. He was terminated, so he returned to New York. His only credits for Davis were Mouse Menace (released 1946), The Foxy Duckling (released 1947) and The Pest That Came to Dinner (released 1948).

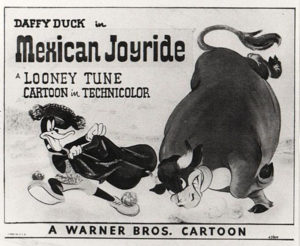

Story man Dave Monahan made a brief sojourn to the studio after his military service, and is credited on such films as Mexican Joyride and Catch as Cats Can (both released in 1947). After two other cartoons, Monahan left to work as a story man at Screen Gems. Meanwhile, Lloyd Turner, an in-betweener in the McKimson unit, strived to become a writer at the studio. With the help of McKimson’s chief story man Warren Foster, Turner secured the position and was teamed with Bill Scott, also by the summer of 1946. Scott recalled in a 1978 interview that Davis was “worried, nervous, and not at all sure of himself or of the two fledgling writers foisted on him, but he was always nice to us.” However, a decade later, Davis praised Scott’s abilities to Michael Mallory, mentioning he was “an excellent story man.” Turner recalled that their first cartoon, Doggone Cats (released 1947), was reworked after an ineffective jam session that occurred earlier.

Story man Dave Monahan made a brief sojourn to the studio after his military service, and is credited on such films as Mexican Joyride and Catch as Cats Can (both released in 1947). After two other cartoons, Monahan left to work as a story man at Screen Gems. Meanwhile, Lloyd Turner, an in-betweener in the McKimson unit, strived to become a writer at the studio. With the help of McKimson’s chief story man Warren Foster, Turner secured the position and was teamed with Bill Scott, also by the summer of 1946. Scott recalled in a 1978 interview that Davis was “worried, nervous, and not at all sure of himself or of the two fledgling writers foisted on him, but he was always nice to us.” However, a decade later, Davis praised Scott’s abilities to Michael Mallory, mentioning he was “an excellent story man.” Turner recalled that their first cartoon, Doggone Cats (released 1947), was reworked after an ineffective jam session that occurred earlier.

Due to the shortage of Technicolor materials after World War II, which affected most animation studios, much of Davis’ output released in 1947 and 1948 were processed in Cinecolor. Scott and Turner remained as his story men for nearly a year, writing such cartoons as Two Gophers from Texas (released 1948), What Makes Daffy Duck (released 1948), A Hick, A Slick and a Chick (Davis’ personal favorite, released 1948) and Bowery Bugs (released 1949), Davis’ only Bugs Bunny cartoon. Eventually, Scott and Turner each were required to submit a solo story; the one selected would remain on staff. Scott was fired from Warners, and Turner remained as Davis’ chief story man. By the summer of 1947, the inner workings of studio politics began to disrupt the Davis unit. Reportedly, his cartoons were not received warmly as the other directors by the top brass at Warners. After three cartoons on his own, Turner was given an ultimatum to return to in-betweening department or leave; he chose the latter.

Sid Marcus became Davis’ story man after Turner’s departure. Their teaming sired one official release, Bye, Bye Bluebeard (released 1949). By November 1947, the decision to minimize costs at Warners called for three directorial units instead of four. With the least seniority, Davis was eliminated. No matter the circumstances, it seemed the fourth unit—whoever was in its place—was affected by a six-month probationary contract, which became operative after Leon Schlesinger sold the studio. Bob McKimson finished Marcus’ story for A Ham in a Role (released 1949), which was only in the dialogue recording phase when Davis’ unit dissolved. Marcus was laid off from the studio after Davis’ unit was discontinued. Davis lent his own perspective as he explained, “I wasn’t one of the gang. They [the other directors] had the advantage that they were working together for quite a while and played off each other. I never had that advantage.”

Friz Freleng invited Davis to join his unit as an animator, which he found more satisfying than as a director. He recalled that his wife Rae Kessler encouraged the changeover, claiming he had a “grouchy” disposition when directing. Around later 1952, he wrote the story for the Oscar-nominated Tweety/Sylvester cartoon Sandy Claws (released 1955), which is credited to both Warren Foster and Davis, though he claimed Foster’s only contribution was presenting the storyboard to Freleng. Davis remained with Freleng until 1953, when the studio shut down in the wake of 3-D films. He chose the same fallback position as manager of a liquor store.

In November 1953, Davis returned to Warners, where he continued to work as an animator for Freleng. The names of his assistant animators during his time as an animator in the 1940s and 1950s are uncertain, with the exception of Art Leonardi, hired at the studio in 1957. By the end of the 1950s, the studio initiated its own television unit under producer David DePatie.

In November 1953, Davis returned to Warners, where he continued to work as an animator for Freleng. The names of his assistant animators during his time as an animator in the 1940s and 1950s are uncertain, with the exception of Art Leonardi, hired at the studio in 1957. By the end of the 1950s, the studio initiated its own television unit under producer David DePatie.

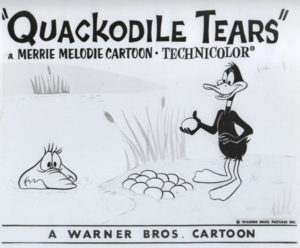

In June 1960, as the production schedule required additional theatrical and television productions, Davis became embittered with the studio’s operations. After he was promised a unit for commercials, Davis recruited his staff, but another animator was brought on in his place. Presumably, Phil Monroe was the aforementioned client, since he returned to Warners that year after leaving in the early 1950s, and had gained experience as a director of commercials in the interim. He left Warner Bros. for Hanna-Barbera, during which, he directed the 1962 Daffy Duck cartoon Quackodile Tears on a freelance basis as a favor for Friz Freleng, as he recalled to Michael Barrier, providing character layouts and a meeting with the animators.

Davis worked as an animator at Hanna-Barbera for a brief period. He was promoted to story director on The Flintstones and The Yogi Bear Show, drawing production boards and timing scenes for dialogue and action.

While Davis continued as a story director at Hanna-Barbera, he also worked as an animator at Walter Lantz’s studio on theatrical shorts under directors Jack Hannah and Sid Marcus. He also animated on the feature film Gay Pur-ee (1962), produced at the UPA studios and distributed by Warner Bros. When he switched to DePatie-Freleng near the end of the 1960s, He soon became a director again. Davis handled much of the production workload, including their theatrical shorts, television programs and interstitials. Much like his earlier career at Mintz/Screen Gems, Davis would animate small sections of his cartoons for DePatie-Freleng.

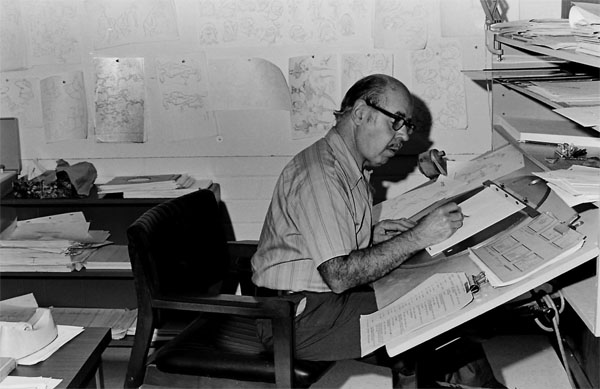

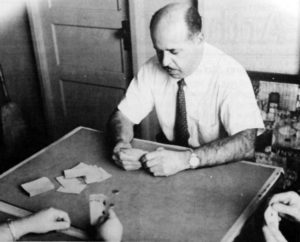

Davis at DePatie Freleng in 1972

Throughout the 1970s, Davis worked continuously on a freelance basis as a consultant at Hanna-Barbera and as a director at DePatie-Freleng. By the 1980s, he stuck mostly with Hanna-Barbera as a timing director on several television shows, mailing work to Hollywood from his home. Near the end of his career in animation, producer Ralph Bakshi offered Davis to work for him, but he declined. He officially retired in 1988, and relocated to Stanford near Palo Alto with his children. Later in life, he was friendly to animation enthusiasts who spoke with him about his career. However, unlike many of his peers, such as Freleng and Jones, he was unaccustomed to praise, as he spoke to Michael Mallory, “I’m very reticent about blowing my own horn.” During a telephone call, Mike Kazaleh received this reaction from Davis: “This is a long-distance call; you know that, right?”

In 1994, Davis received the Winsor McCay Award for Lifetime Achievement for his contributions to the animated medium. Davis resided at Sunnydale in the mid-1990s, where he soon acknowledged the admiration from his work, responding to letters and correspondence. He passed away on May 9, 2000 at the age of 94.

Addendum

• If some of you may be confused about the chronology when Davis became a director for Warner Bros., I have provided compiled this information for further clarification. Click Here.

• To see examples of Art Davis’ animation for Warner Bros., here is an animator reel from Thad Komorowski…

• Lastly, Since this post has landed directly on this occasion, here’s Halloween (1931) featuring Toby the Pup, with animation by Art Davis (with Dick Huemer and Sid Marcus, too!)

Until then, folks, I’ll be back in December! Keep a lookout for updates from me on upcoming restorations on the Thunderbean Animation Facebook page…

(Thanks to Jerry Beck, Michael Barrier, Yowp, Michael Mallory, Charlie Judkins, Steven Hartley, Thad Komorowski, Joe Campana, Mike Kazaleh, Charles Brubaker and Jim Korkis for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Next to Virgil Ross, Art Davis was responsible for my favorite animation in Friz Freleng’s cartoons during the ~1950-1955 period. I didn’t like his work as much after the ’53 shutdown- it had the same energy as before but the in-betweens weren’t as good and some strange designs came out at times (see “This is a Life?” and certain shots of Daffy in “Show Biz Bugs” and “Person to Bunny”, for example).

And I love his directorial stint, with “The Stupor Salesman”, “Riff Raffy Daffy”, “Odor of the Day”, “Holiday for Drumsticks”, “Doggone Cats”, and “Bowery Bugs” being my favorites. I didn’t mind that they had a different feel than what Jones, Freleng, and McKimson were putting out, because variety is always a good thing in animation. Plus this was where Emery Hawkins was really given a chance to shine.

A very good article on Art Davis. I wish his brother Mannie had more freedom in directing at Terrytoons if Terry wasn’t such a cheapskate. You could tell that most of the directors there wanted to break free from the producer’s rules.

“Reportedly, his cartoons were not received warmly as the other directors by the top brass at Warners.”

Why am I not surprised? Stupid Suits. Didn’t one of them once think WB produced Mickey Mouse cartoons?

Art’s 40s cartoons are topnotch, easily on par with the other guys there.

Suits ruin everything.

Great write-up, Baxter! I’ve always liked Davis’ WB shorts, and it’s nice to see an in-depth history on him.

I guess it’s for the best that his unit went out the way it did if he wasn’t really enjoying it, but his cartoons were very funny. Dare I say that for the late-40s many of his shorts are funnier than a lot of what Friz Freleng or even Chuck Jones was doing (although their cartoons were still terrific).

Great job as usual, Devon. I learned much about Art’s life that I never knew. He was a private man who gave up little about his past to me through our brief association, which was 1995-1998. I love your in depth research.

“What makes Daffy Duck” ‘s animation always seemed so much more energetic and loose than most of his work, almost makes me think it was supposed to be a Clampett cartoon.

I’m with Davis on A Hick etc being his favorite; I recall reading about that. It’s one of the only times besides Jones’s three bears 🐻 that Bea Benaderet and Stan Freberg we’re in the same cartoon, at least at Warner’s.

I interviewed Art Davis for the Salt Lake Tribune in 1994. He was living in the area then. During the interview, which was a lot of fun and informative, he sketched Yosemite Sam and Tweety Bird. They are now framed.

His last Phantasy is Who’s Zoo in Hollywood (1941) not The Way of All Pests

I was fortunate enough to interview Mr. Davis for my newspaper the Salt Lake Tribune sometime in the early to mid-1990s. He was living in Salt Lake City at the time and spent a wonderful hour or so talking about his career. I was a big fan of his work (but didn’t realize how much until I did my research for the interview). During the interview, and to my delight, he created a quick sketch of Yosemite Sam and Tweety Bird, which is now framed and on my living room wall.

This is about my Uncle Art! I have a drawing of Wilma and Betty talking about coming to visit me in NY as a little girl–a Christmas present from him and my Uncle Mannie! So cool to stumble upon this!