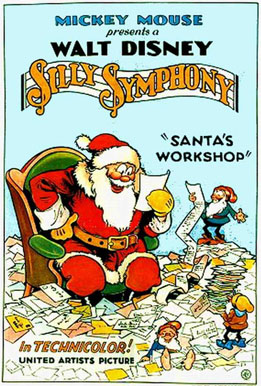

Next on the holiday line-up is an early color Silly Symphony, with Santa Claus and his merry little gnomes!

Next on the holiday line-up is an early color Silly Symphony, with Santa Claus and his merry little gnomes!

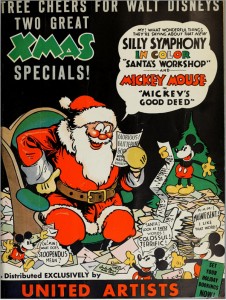

In the summer of 1932, Walt Disney announced a new distribution deal with United Artists ─ a company built on independent creative control in the motion picture industry by its founders Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D.W. Griffith. United Artists granted an advance of $15,000 per cartoon ─ more than double what Disney received from Columbia Pictures. Displeased with Columbia’s budgets, the studio signed with United Artists in December 1930, a year and a half before their new cartoons were released under this agreement.

Their new arrangement with UA allowed Disney to produce his Silly Symphonies in color. Flowers and Trees became the first film produced in three-strip Technicolor. This film was intended to experiment with this new method, and showcased a full range of colors that made previous color processes (literally) pale in comparison. An immense sensation when released on July 1932, Disney decided all future Silly Symphonies would be made in color, while the Mickey Mouse series proceeded in black and white until early 1935.

Santa’s Workshop – originally titled Santa’s Toy Shop ─ was the fourth color Silly Symphony. The quick production schedule slated the cartoon for an early December release for the Christmas season; the story outline was approved on September 1932, with animation and layout underway in October. Besides using color in the series, the UA contract allowed Disney’s studio to use high fidelity RCA sound, though the previous Powers Cinephone system is credited on the main titles.

The studio also experimented with casting principal human characters in the Silly Symphonies. In contrast to the pliable animation of the hunters from 1931’s The Fox Hunt, Disney’s cartoons from UA attempted plausibility with such characters. For instance, the introductory scenes of Santa Claus (voiced by Walter Geiger), reading children’s letters to his scowling secretary (voiced by Pinto Colvig), required this type of engaging credibility in order to engross audiences, especially with a film depicting the jocular St. Nicholas.

The studio also experimented with casting principal human characters in the Silly Symphonies. In contrast to the pliable animation of the hunters from 1931’s The Fox Hunt, Disney’s cartoons from UA attempted plausibility with such characters. For instance, the introductory scenes of Santa Claus (voiced by Walter Geiger), reading children’s letters to his scowling secretary (voiced by Pinto Colvig), required this type of engaging credibility in order to engross audiences, especially with a film depicting the jocular St. Nicholas.

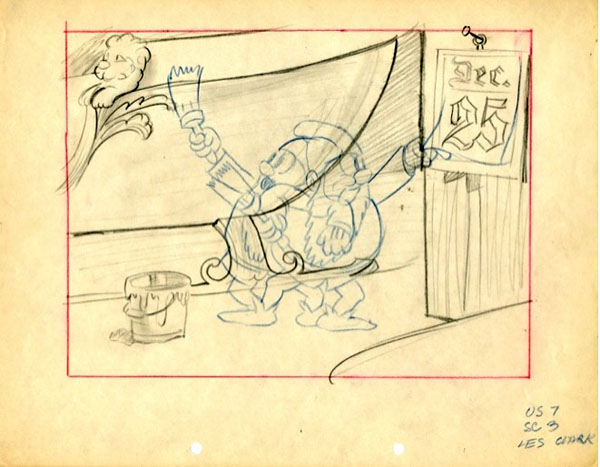

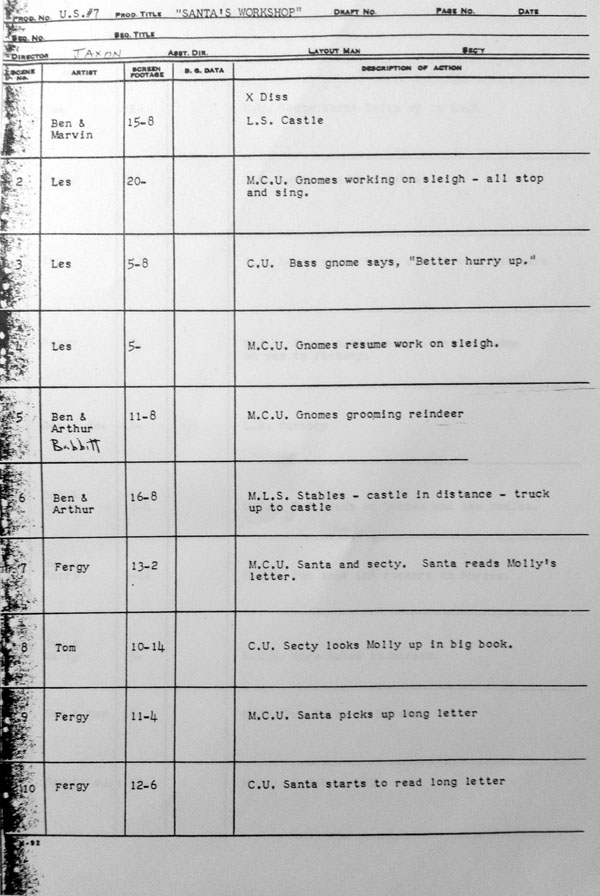

The animators on Santa’s Workshop are comprised of a few experienced artists, such as Les Clark, Norm Ferguson, Tom Palmer and Jack King, with Gerry Geronimi and Eddie Donnelly handling brief sequences. Like Ferguson, King and Geronimi, Donnelly moved from the East Coast; he left the Van Beuren studio on March 1932 and animated on a few Silly Symphonies. He left Disney’s and arrived back to Van Beuren, for reasons unknown, in April 1933. He remained in the East Coast, animating/directing for Van Beuren, and later for Terrytoons as one of the three principal directors (along with Connie Rasinski and Mannie Davis).

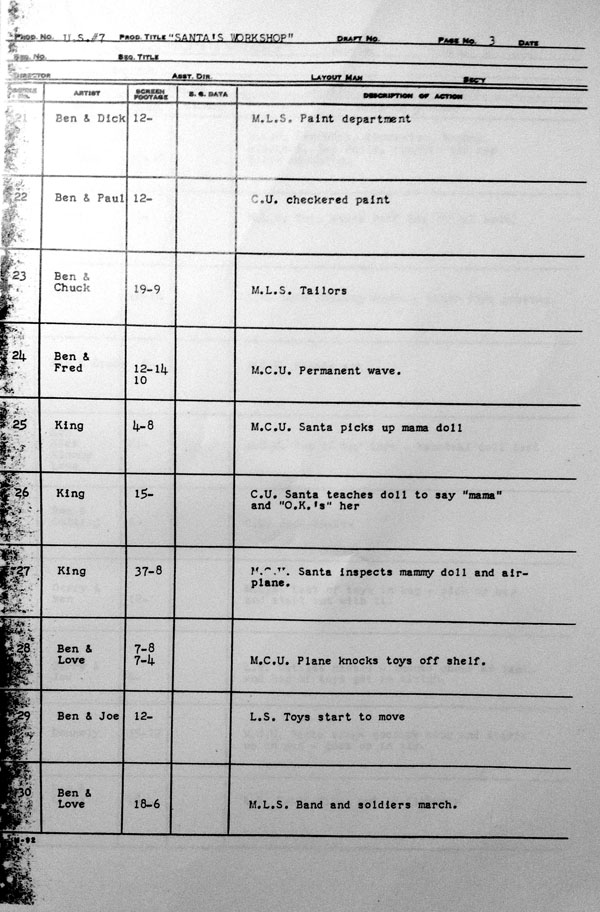

Disney’s higher budgets, brought along by the UA contract, allowed sequences with multitudes of characters that brim with activity and movement. The Christmas theme for this cartoon is rife with potential in these regards, especially in scenes with Santa’s little gnomes preparing for Christmas Eve; the gnomes tending to Santa’s reindeer, mass-producing children’s toys in an assembly line, and the toy parade (marching along to Schubert’s March Militare) are reliant on cycles. Such scenes were assigned to less experienced animators trained under Ben Sharpsteen’s auspices ─ hence, the draft credits the artists with their assignments alongside Sharpsteen.

Disney’s higher budgets, brought along by the UA contract, allowed sequences with multitudes of characters that brim with activity and movement. The Christmas theme for this cartoon is rife with potential in these regards, especially in scenes with Santa’s little gnomes preparing for Christmas Eve; the gnomes tending to Santa’s reindeer, mass-producing children’s toys in an assembly line, and the toy parade (marching along to Schubert’s March Militare) are reliant on cycles. Such scenes were assigned to less experienced animators trained under Ben Sharpsteen’s auspices ─ hence, the draft credits the artists with their assignments alongside Sharpsteen.

These artists include Ham Luske, Ed Love, Harry Reeves (a former artist from Pat Sullivan’s studio), Fred Moore, Jack Kinney and Art Babbitt. George Drake, formerly Dick Lundy’s assistant, supervised the in-betweeners in their own department around the time Workshop was in production. Drake might’ve assigned himself isolated scenes in the early ‘30s to technically stipulate his status as an instructor; he handles the Noah’s ark toy in scene 34. The draft credits three or four artists in shots where the toys follow each other ─ rather than toys used as a focal point for gags, as others pass by ─ during the toy parade, indicating certain artists handled specific toys (i.e., Kinney animates the wind-up elephant and donkey in scene 31.)

Out of all the trainees, Babbitt’s scenes are distinguishable in this cartoon; scene 5 is plainly more fluid than Clark’s animation. Babbitt convincingly animates one of the gnomes struggling to pitch hay in the following scene. (The written surname “Babbitt” under scene 5 of the draft is author Russell Merritt’s handwriting.) Readers may notice that scene 39 of Santa singing his farewell to his gnomes (animated by Eddie Donnelly) is divided into two parts in this cartoon. In the draft, it is only depicted as one shot; however, recent research indicated that the later draft typed after ─ not displayed here─ rectified this change.

Out of all the trainees, Babbitt’s scenes are distinguishable in this cartoon; scene 5 is plainly more fluid than Clark’s animation. Babbitt convincingly animates one of the gnomes struggling to pitch hay in the following scene. (The written surname “Babbitt” under scene 5 of the draft is author Russell Merritt’s handwriting.) Readers may notice that scene 39 of Santa singing his farewell to his gnomes (animated by Eddie Donnelly) is divided into two parts in this cartoon. In the draft, it is only depicted as one shot; however, recent research indicated that the later draft typed after ─ not displayed here─ rectified this change.

I’d like to announce the new revised publication for J.B. Kaufman and Russell Merritt’s Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series. The original edition, published by La Cineteca del Friuli and distributed by a university press, is extraordinarily pricey. Disney Editions will publish this new edition, sometime around 2016. (As a matter of fact, one of the revisions in the book is the voice for Santa Claus in this cartoon.) Keep an eye out!

Enjoy this breakdown video! Listen for Walt Disney himself as one of Santa’s helpers.

(Thanks to J.B. Kaufman, Michael Barrier, and Keith Scott for their help)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

One of my all time favorite Christmas cartoons! Fun fact: The voice of the elf who Santa gives Billy Brown’s wish list and tell him to add a cake of soap with the Noah’s Ark toy was performed by Walt Disney!

My favorite scenes are when the elf used a rubber spider to cause the doll’s hair to rise in fright so he could curlers to fix the hairs and when that one Pickaninny doll came down the chute and shouted “Mammy!!” so Santa and stamped her bun with the “OK” approved stamp (even thought this scene is now censored for TV broadcast thanks to the politically correct censors).

Friend, in the US “pickaninny” is not a word we use in polite conversation.

Call it political correctness if you like. It’s actually about acknowledging that offensive language can be hurtful.

This cartoon was such a big part of my kidhood – and the sequel, “The Night Before Christmas” even more so. I love the Northern Lights effects, the wooden-blocks look of many of the toys, and just the sheer amount of inventive detail in every scene.

“i.e., Kinney animates the wind-up elephant and donkey in scene 31.”

Did you find out who-animated-what in these parade scenes from exposure sheets, or is it guess work?

One of my favorite Christmas cartoons! My grandma had this cartoon on the video “A Walt Disney Christmas.” Unfortunately, it was a re-release print with the Mammy scene cut out. I love the Schubert’s Military March music used when the toys march into Santa’s bag.

Yep, saw this on TCM’s “Treasures of the Disney Vault” (Except they cut out a significant portion of the cartoon; namely the blackface toys).

Kinda sad that TCM of all channels is censoring its content.

I’m going to assume it was either a goof (aired the censored version by mistake) or was a mandate by Disney they had to adhere to.

I wonder if any exhibitors booked the two Santa cartoons together. Since “Night Before Christmas” came out the following year, exchanges very conceivably had ample prints of “Santa’s Workshop” still in stock.

With all the discussion of making humans more plausible, it’s noteworthy how hard they work to make the mechanical toys plausible (if not always possible) as well.

To understand the early work of almost all the other studios, you have to enjoy a SILLY SYMPHONY or two; I not only say this with regard to style and technique, but also because some of the people directing at the other studios worked alongside Walt Disney to create some of these stunning cartoons. This is a fantastic example.

@Peter Mork

According to Wikipedia:

The term was also used to describe Austrailian Aborigines by the Anglo settlers. The first usage of the term Pickaninny was in 1693. The term was used as a word of endearment but now it’s considered as a racist term. BTW in San Bernardino County California there’s a butte named Picaninny Buttes that is located there and there are people who want the name of the butte changed. And in Western Australia there’s a creek called Piccaninny Creek which the Piccaninny Crater was named after. This might considered as racist but this was the 1930’s and thats how the animators thought it was funny along with stereotypical views of the Chinese, Japanese, Jews and many others.

Thanks for the history lesson. I’m not especially concerned with what was acceptable in the 1930s. We watch these old films and make allowances. Now it is 2015. You used a distasteful term which wasn’t even in the film being discussed. I recommend against that.

It’s an antiquated term in the modern day. No one uses it anymore, not even ironically.

Crediting oddity: scene 37 credits “Gerry” and “Ben”, but Geronimi wasn’t one of Ben’s trainees. Maybe Ben animated the gnomes carrying the sack. The next shot credits “Gerry” and “Joe” but no Ben, even though Joe D’Igalo was one of Ben’s trainees.

“Readers may notice that scene 39 of Santa singing his farewell to his gnomes (animated by Eddie Donnelly) is divided into two parts in this cartoon. In the draft, it is only depicted as one shot; however, recent research indicated that the later draft typed after ─ not displayed here─ rectified this change.”

Santa’s movements suggest it was the same piece of animation, pulled out to a wider field, but in the first shot the sleigh and sack are part of the background, and in the second shot they are part of the animation.

According to Shaus Culhane, it was the actual members of the Ethnic groups(save Blacks)who put the Ethnic caricatures in. Maybe the Jewish stereotype was put in by a Jewish artist. (I don’t know, because Culhane was talking about Fleischer, not Disney).