Like Warren Foster, Michael Maltese was born and raised in New York City. Unlike Foster, he was involved in the arts early on in his career. The 1930 NYC Census lists his occupation, at age 22, as an artist, specifically in painting. Maltese first started in the animation industry at Max Fleischer’s studio, as a cel painter, on July 1935. He rose from opaquer to in-betweener by the end of the year. By April 1936, Maltese married Florence “Florrie” Sass, with Warren Foster as his best man.

He wanted to become an assistant animator at Fleischer’s, but the studio wouldn’t allow such a quick progression. Maltese moved to Detroit to work for Jam Handy’s studio, which specialized in commercial and industrial films.

After his two-month stint for Jam Handy, Maltese moved to Hollywood, and was hired at Warners as an in-betweener on May 1937. Similar to Fleischer’s Animated News, the animation department’s in-house magazine, The Exposure Sheet, provided a glimpse into the studio life from the artists’ perspective. Evidently, the front office was fascinated by Maltese’s comic pieces for the newsletter, and he moved to the story department in August 1939.Maltese started in the general pool of story men, designated by two rooms— the “Kansas City Boys” (Ben Hardaway, Jack Miller and Melvin “Tubby” Millar) and a group of younger story artists including Rich Hogan, Cal Howard, Dave Monahan and Tedd Pierce. In You Ought to Be In Pictures (1940), directed by Friz Freleng, Maltese appeared on screen as a studio security guard, albeit with dialogue dubbed by Mel Blanc. Maltese didn’t receive screen credit on a story until 1941’s The Haunted Mouse, directed by Tex Avery, in which his surname misspelled as “Malteze.”

Friz Freleng with Maltese

Maltese and Pierce contributed to other studios’ cartoons, as well; at Columbia’s Screen Gems studio—with Bob Clampett serving as a story editor—assisting on the stories for Boston Beanie and Cockatoos for Two (both released in 1947). Maltese and Pierce—along with Jones and Freleng—were also recruited to enliven the story for UPA’s first theatrical release, Robin Hoodlum, released in 1948. (Though uncredited, Robin Hood’s line in the film, “Good day, good knight!” seems like a Maltese contribution.)

Around the summer of 1946, he left the studio to undergo back surgery. As he recuperated, Maltese wrote a story for Warners, but was compensated as if he were an outside writer. After an anonymous complaint about his payment was reported to producer Eddie Selzer, Maltese thought the source was Pierce, which led to friction between the two. From then on, Maltese worked exclusively with Jones, while Pierce worked with Freleng. As a director, Jones was aware of Maltese’s rich gag sensibilities, giving him complete freedom in putting the stories together. These particular strengths from Jones and Maltese, as they focused on strong character comedy, marked an exceptional oeuvre in the studio’s output during the late ‘40s and early ‘50s.

When Warners’ animation department closed in June 1953, Maltese had already moved to Walter Lantz’s studio, presumably as a freelancer, since he wasn’t on the payroll until January 1954. He wrote for director Paul J. Smith—formerly an animator for Warners—on such films as Real Gone Woody (1954), which featured a teenaged Woody Woodpecker and Buzz Buzzard rivaling against Winnie Woodpecker (in her screen only appearance), and The Legend of Rock-a-Bye Point (1955), directed by Tex Avery.Maltese returned to Warners in August 1954, after Jones negotiated a pay raise.

He continued to write Jones’ theatricals until around October 1958, when he called Joe Barbera at his new studio, which produced cartoons for television, to write for their programs. By December, after he settled in Hanna-Barbera, he became the head of the story department and wrote a significant amount of output for the studio, including the entirety of the Quick Draw McGraw series. He wrote on the Huckleberry Hound Show, The Yogi Bear Show and The Flintstones throughout the early ‘60s.

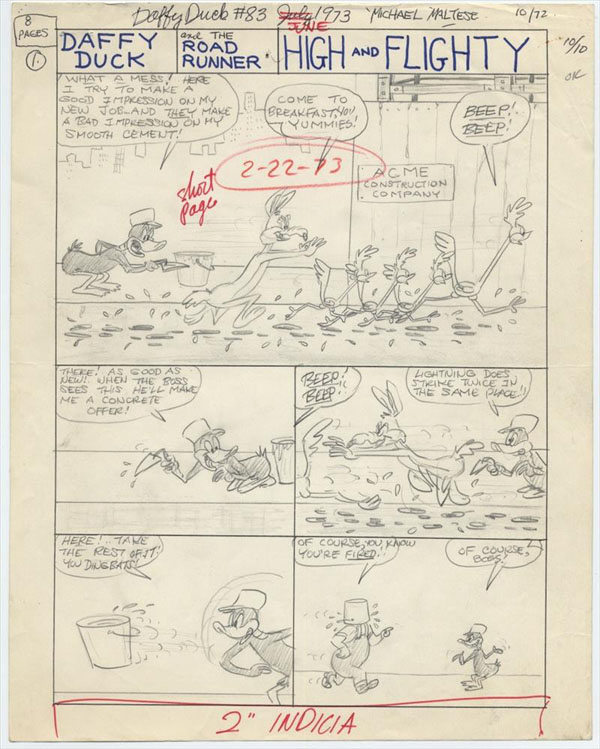

He went to work with Chuck Jones again in August 1963, on a revived series of Tom and Jerry cartoons released by MGM. Two years later, he was back at Hanna-Barbera, working on Secret Squirrel, Wacky Races and its spin-off series, Dastardly and Muttley in Their Flying Machines. During the ‘70s, Maltese wrote for Gold Key comics with Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Beep-Beep the Road Runner (which differed greatly from the screen version), Woody Woodpecker and the Pink Panther, among others. One of his last contributions before his 1981 death was for Jones, co-writing a revival short entitled Duck Dodgers and the Return of the 24 ½ Century, used as part of the 1980 TV special Daffy Duck’s Thanks-for-Giving Special.

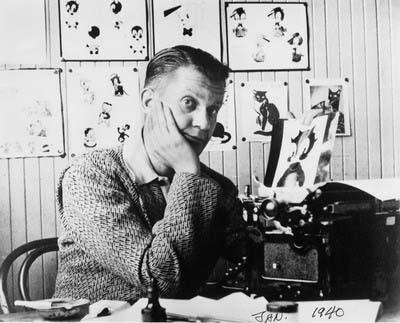

Maltese in 1940

Maltese freelanced in writing “funny animal” comic stories for the Sangor/Davis shop—for Coo Coo, Giggle, Goofy, Ha-Ha and Barnyard Comics—published between 1945-48. Different motifs and character types from the Maltese-written Warners cartoons from this period permeate throughout:

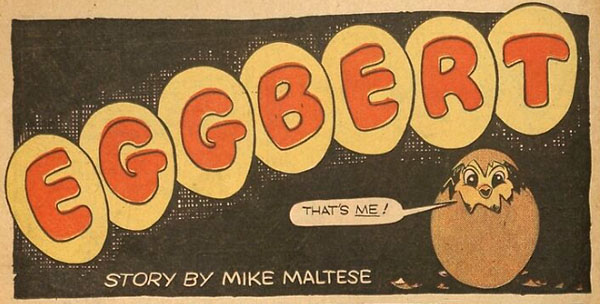

• The street-smart rowdies who torment the newborn baby chick “Eggbert”, in a story published for Coo Coo Comics #17 (May 1945, artist unknown).

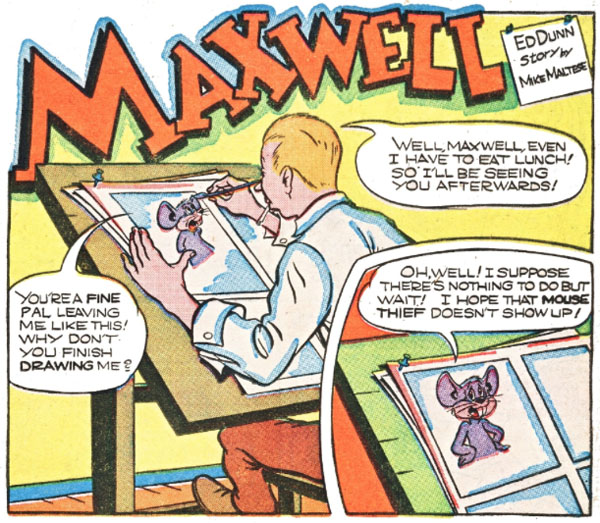

• The small, persecuted creature retaliating against a bigger enemy in his own methods, as “Maxwell” the mouse does, retaliating against the cat after inexplicably turning invisible, in this story from Ha-Ha Comics #28 (April 1946).

• The scheming duo psychologically manipulating a threat bigger than them, in a manner similar to Hubie and Bertie’s mind games against Claude Cat, is a theme used in the “Raymond Goat” story for Coo Coo Comics #31 (January 1947).

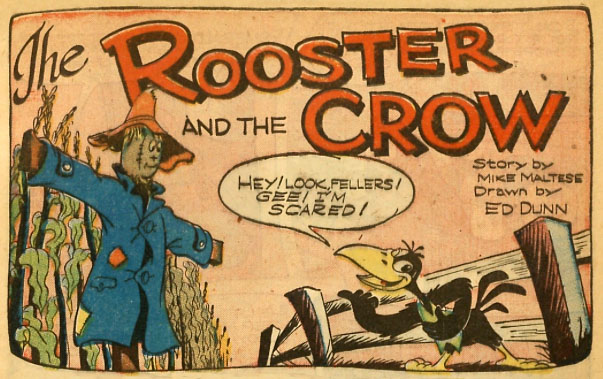

• Swindling cheats who dupe their adversaries by disguise, a staple in other studios’ cartoons, but remains sharp in Maltese’s usages, as it does in “The Rooster and the Crow”, used for Barnyard Comics #10 (February 1947).

• On the subject of disguise, heroes who masquerades themselves to outsmart uncouth characters, such as the feeble donkey who fashions a “dried-up old steer skull” to deceive the robber’s horse, in the “Donkey-Oaty” story from Goofy Comics #24 (February 1948).

The Dell and Gold Key from the ‘60s and ‘70s, presumably written by Maltese, are unsigned but still carry similar earmarks to his unique humor/dialogue. Harvey Eisenberg drew the Quick Draw McGraw story, the Bugs and Daffy stories is drawn by animator Phil DeLara and the Super Goof story by Pete Alvarado, each of whom were veterans in theatrical animation.

• “Stagecoach Magic”—Quick Draw McGraw #4 (October-December 1960).

• “Excess Baggage”—Bugs Bunny #94 (July 1964).

• “Some Ducks Have More Feathers than Friends”—Daffy Duck #40 (March 1965).

• “Blank Deposit”—Super Goof #23 (November 1972)

1972 comic book story by Michael Maltese

(Thanks to Michael Barrier, Yowp and Joe Torcivia for their help.)

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

DEVON BAXTER is a film restoration artist, video editor, and animation researcher/writer currently residing in Pennsylvania. He also hosts a

Anyone know who the letterer is on the Bugs, Daffy, and Quick Draw stories posted here?

I got to talk to Michael Maltese once on the phone. He told me that for the Hanna-Barbera cartoons, he just recycled his old Warner Brothers gags.

I’ve long been curious about Maltese’s methods. The article includes a photo of him behind a typewriter. How much of his work was written at a board and how much was scripted? No one I’ve asked seems to have a sense of it.

Did Mike Maltese ever say what he had done at Jam Handy? A Coach for Cinderella or A Ride for Cinderella could have in production while Maltese was there.

I remember the Road Runner comic books. I noticed that the Road Runner had three nephews that each spoke in rhyme. Wonder if they were capitalizing on the “nephews” trend like in the comics and cartoons like Popeye (he had four then was reduced to three) and of course Donald Duck’s three nephews.

Maltese also wrote an entire Hanna-Barbera series about a certain, veyr famous Bert Lahr./Cowardly Lion obsessed Mountain Lion who always said: Heavens to Murgatroyd….Snagglepuss,even!

It’s amazing how many studios, publishers, and other employment opportunities there were for talented comics artists in those days. Even during the Depression.

The main letterer for the L.A. office of Western Publishing during the time Mike wrote for them was Rome Siemen.

Mike worked at a typewriter sometimes, with a pencil sometimes. I discussed it with him and he had no real explanation why he did it one way on one project and another way on another.

Very clever, funny man.