The heat is on – again, as animated characters from all walks of toondom keep on their toes to avoid the ultimate in hotfoots. More action from the later 30’s, as the sirens continue to blare and the bells sound in alarm. Notably, we’ll continue to deal with the plight of the nearly obsolete fire horse, the subject of two different episodes – and also encounter two films capitalizing on a famous fire of old, recently exploited at the time by a high-grossing live-action feature. Also, we’ll get a bit controversial, with two cartoons whose subject matter is a bit “too hot to handle”, even today, for the tiny tykes.

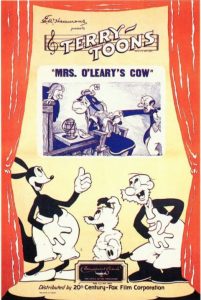

Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow (Terrytoons/Educational, 7/22/38 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.) is nearly a cheater – recycling many scenes and adapting other from several Terry cartoons we’ve seen before. The truncated version presented by CBS cuts into the middle of a trial of the famous bovine, accused of starting the Chicago fire (recently the subject of a successful Fox feature, “In Old Chicago”). The cow admits to recognizing the incriminating lantern, and tells in a flashback how the unfortunate incident occurred, claiming that she was helping Mrs. O’Leary with the laundry chores, when a big bumblebee flew in the window, landing on her nose. Reaching for something to chase it away, she makes the mistake of grabbing the lantern and flinging it across the room, setting the barn on fire. She races out into the street, and performs a marvelous impersonation of a fire siren, her large teeth whirling inside her mouth spirally to simulate the workings of such a device. Now begin the old clips. Hook and ladder trucks curve out of a station house – clipped right out of “Fireman, Save My Child”. A new shot has such a truck take a sharp corner by the rear wheelman pivoting the ladder around the engine cab until it is pointed in the right direction, then the cab taking over to proceed forward again. The everybody-in-town-follows-the-engine shot, reversed right to left, is repeated from Hook and Ladder No. 1. A redrawn version of the lengthy sequence of a fireman rising from bed at the sounds of the engines, going through am extended morning grooming routine, then back to bed again, is repeated from Hook and Ladder No. 1. The shot of engine hitting the curb and launching four ladders up against the building is repeated from Fireman, Save My Child. Finally, we begin to see some new animation, but beginning with two old gags – dog runs up ladder but shoots past the end – he falls back on upper rung, and squirts a fire extinguisher into the window, but the flame grabs it and shoots it back at him.

Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow (Terrytoons/Educational, 7/22/38 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.) is nearly a cheater – recycling many scenes and adapting other from several Terry cartoons we’ve seen before. The truncated version presented by CBS cuts into the middle of a trial of the famous bovine, accused of starting the Chicago fire (recently the subject of a successful Fox feature, “In Old Chicago”). The cow admits to recognizing the incriminating lantern, and tells in a flashback how the unfortunate incident occurred, claiming that she was helping Mrs. O’Leary with the laundry chores, when a big bumblebee flew in the window, landing on her nose. Reaching for something to chase it away, she makes the mistake of grabbing the lantern and flinging it across the room, setting the barn on fire. She races out into the street, and performs a marvelous impersonation of a fire siren, her large teeth whirling inside her mouth spirally to simulate the workings of such a device. Now begin the old clips. Hook and ladder trucks curve out of a station house – clipped right out of “Fireman, Save My Child”. A new shot has such a truck take a sharp corner by the rear wheelman pivoting the ladder around the engine cab until it is pointed in the right direction, then the cab taking over to proceed forward again. The everybody-in-town-follows-the-engine shot, reversed right to left, is repeated from Hook and Ladder No. 1. A redrawn version of the lengthy sequence of a fireman rising from bed at the sounds of the engines, going through am extended morning grooming routine, then back to bed again, is repeated from Hook and Ladder No. 1. The shot of engine hitting the curb and launching four ladders up against the building is repeated from Fireman, Save My Child. Finally, we begin to see some new animation, but beginning with two old gags – dog runs up ladder but shoots past the end – he falls back on upper rung, and squirts a fire extinguisher into the window, but the flame grabs it and shoots it back at him.

An original gag has another dog fireman hook up the hose to hydrant, which as usual is too short to reach the building – so he walks over to the hydrant, and with great effort pushes it through the ground to stretch the plumbing another ten feet closer to the building. When he gets the hose over to the blaze, there is still nothing coming out. “WATER!”, he yells. A deluge of buckets of the stuff pours onto him from people in the upstairs windows. The Chief limbers up against a lamppost as if a prize fighter in his corner before the bell, while a crowd around him chants “Fight those flames!” As a bell sounds, he enters the building, and literally dukes it out with a personified flame-man. The flame gets in a blow on the seat of the chief’s pants, and he runs for his corner, where the other firemen have a waiting bucket of water ready for him to sit in. He enters again with a hose, but the flames merely jog over the top of the stream of water, regroup into a larger flame-man, and give chase once again. Cornering the chief against a wall, the flame playfully tickles the chief’s belly with one fiery finger. “Don’t ever DOOO that”, responds the chief, in his best Joe Penner impression. We lose track of the chief for the remainder of the cartoon, cutting outside for a barrage of furniture and various belongings being thrown out of each window of the building. Below, each fire fighter waits in turn to catch one object or another. One unlucky soul has a cast-iron stove dropped upon him, and pops up from under the stove lids to inquire, “Who thew that?” A leak in the hose has one fireman attempt to plug the same by taking the section of hose in his mouth and clamping down his jaws – only to have water shoot out his ears. A few more old gags and some animation are retreaded, as axe-wielding firemen chop every item removed from the building in two, while four fireman aim hoses at the building from a roof across the street – lifted from “Fireman, Save My Child” – while persons from the building use the water for the old “bridging” gag to get across the street. That’s it for the fire crew, as the police now arrive, and set upon capturing the cow as prime suspect, carting her away in the “Black Maria” paddy wagon. Back in the courtroom, the cow concludes, “And so help me, that’s the honest truth…” With a sweeping gesture of her hoof, she knocks over Exhibit A – the lantern, setting the courtroom floor on fire. “Glory be, I’ve done it again”, she exclaims to the audience, and her teeth once again revert to a siren mode, for the iris out.

An original gag has another dog fireman hook up the hose to hydrant, which as usual is too short to reach the building – so he walks over to the hydrant, and with great effort pushes it through the ground to stretch the plumbing another ten feet closer to the building. When he gets the hose over to the blaze, there is still nothing coming out. “WATER!”, he yells. A deluge of buckets of the stuff pours onto him from people in the upstairs windows. The Chief limbers up against a lamppost as if a prize fighter in his corner before the bell, while a crowd around him chants “Fight those flames!” As a bell sounds, he enters the building, and literally dukes it out with a personified flame-man. The flame gets in a blow on the seat of the chief’s pants, and he runs for his corner, where the other firemen have a waiting bucket of water ready for him to sit in. He enters again with a hose, but the flames merely jog over the top of the stream of water, regroup into a larger flame-man, and give chase once again. Cornering the chief against a wall, the flame playfully tickles the chief’s belly with one fiery finger. “Don’t ever DOOO that”, responds the chief, in his best Joe Penner impression. We lose track of the chief for the remainder of the cartoon, cutting outside for a barrage of furniture and various belongings being thrown out of each window of the building. Below, each fire fighter waits in turn to catch one object or another. One unlucky soul has a cast-iron stove dropped upon him, and pops up from under the stove lids to inquire, “Who thew that?” A leak in the hose has one fireman attempt to plug the same by taking the section of hose in his mouth and clamping down his jaws – only to have water shoot out his ears. A few more old gags and some animation are retreaded, as axe-wielding firemen chop every item removed from the building in two, while four fireman aim hoses at the building from a roof across the street – lifted from “Fireman, Save My Child” – while persons from the building use the water for the old “bridging” gag to get across the street. That’s it for the fire crew, as the police now arrive, and set upon capturing the cow as prime suspect, carting her away in the “Black Maria” paddy wagon. Back in the courtroom, the cow concludes, “And so help me, that’s the honest truth…” With a sweeping gesture of her hoof, she knocks over Exhibit A – the lantern, setting the courtroom floor on fire. “Glory be, I’ve done it again”, she exclaims to the audience, and her teeth once again revert to a siren mode, for the iris out.

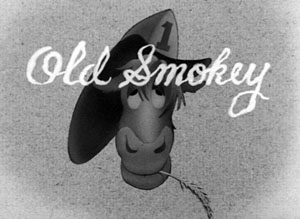

Old Smokey (MGM, Captain and the Kids, 9/3/38 – William Hanna, dir.) – MGM’s ill-fated adaptations of the mock-Germanic comic strip family had a recurring habit of doing things just wrong enough to deprive their projects of either appeal or memorability. This one is something of a case in point. While other directors such as Frank Tashlin were laboring to pack as much action and peril into fire cartoons as possible, the house of Leo somehow finds a way to make almost every gag in this overly-long cartoon come across poky in pacing – something hardly seen in this survey since “Alice the Fire Fighter” in the 1920’s. And what gags we are delivered just aren’t original or creative – practically everything being something we’ve seen before. The scenario isn’t even faithful to the series title, as the “Kids”, Hans and Fritzie, are nowhere to be found in the film, depriving us of any possibility to see how their mischief might have compared to that of Ham and Ex or Scrappy. Cast is thus restricted to the Captain (now changing rank to assume the position of fire chief), the Professor, and Mama – plus a newcomer who is actually an old-timer – a beat up fire horse (whose name isn’t even given except for the title card). The horse is being put out for retirement, upon the Captain’s acquisition of a brand new fire truck. Haven’t we heard this plot idea straight from Scrappy’s “The Fire Plug”? As in the Scrappy cartoon, the old horse is bound for a retirement stable, named “The End of the Trail”. His old pumper wagon is going too, with the Professor charged with the responsibility of seeing to it, sitting in its driver’s seat. “Everything goes but the badge”, says the Captain, removing the shiny number “1″ from the front of the fire horse’s hat, and hanging it upon the radiator of the new engine. The horse weeps, and the Professor controls the reins to slowly prod the horse into the long walk for “the last mile”. The Captain putters for an overly-long time, admiring his new engine, and is just trying out the driver’s seat for size, when the phone rings. It is a call from Mama at home. But it is also a business call, as Mama has somehow set the house on fire, and screams for the Captain to hurry, while black smoke clouds form behind her into humanized shape, and attempt to prevent her call by placing their “hands” over Mama’s mouth to smother her. The Captain starts to sputter, “Well, call the fire departmen….”, before realizing he is the fire department. He climbs back into the engine (with no support crew) and turns the key. As in Scrappy’s “The Fire Plug”, our chief hasn’t bothered to familiarize himself with the machinery, and after gasping and coughing, the engine kicks into gear and barrels out of the station house, with the Captain barely maintaining any control. While Mama beats at the flames with a broom, and is chased out onto the end of a second-story flagpole, where she clings with the flames tickling her rear end, the Captain tries to figure out what lever to pull to have an effect on the engine. He tries the brake handle – and yanks it loose. He finds the gearshift, but is traveling so fast, he passes right by the house as he struggles to change gear. When he finaly does, he shifts into reverse. The engine passes the house again, and rear-ends into a tree. The extension ladder is thrust forward, catching the Captain on its foremost end. The ladder expands with such force, its rungs collide with the metal framework holding the fire bell on the engine hood, so that the framework cuts away every rung of the ladder except the topmost one where the Captain is caught. Then the engine’s machinery aims the ladder straight up, leaving the Captain in the same position as Mickey Mouse and Miny – suspended about a half-dozen floors above the fire, with no visible way down.

Old Smokey (MGM, Captain and the Kids, 9/3/38 – William Hanna, dir.) – MGM’s ill-fated adaptations of the mock-Germanic comic strip family had a recurring habit of doing things just wrong enough to deprive their projects of either appeal or memorability. This one is something of a case in point. While other directors such as Frank Tashlin were laboring to pack as much action and peril into fire cartoons as possible, the house of Leo somehow finds a way to make almost every gag in this overly-long cartoon come across poky in pacing – something hardly seen in this survey since “Alice the Fire Fighter” in the 1920’s. And what gags we are delivered just aren’t original or creative – practically everything being something we’ve seen before. The scenario isn’t even faithful to the series title, as the “Kids”, Hans and Fritzie, are nowhere to be found in the film, depriving us of any possibility to see how their mischief might have compared to that of Ham and Ex or Scrappy. Cast is thus restricted to the Captain (now changing rank to assume the position of fire chief), the Professor, and Mama – plus a newcomer who is actually an old-timer – a beat up fire horse (whose name isn’t even given except for the title card). The horse is being put out for retirement, upon the Captain’s acquisition of a brand new fire truck. Haven’t we heard this plot idea straight from Scrappy’s “The Fire Plug”? As in the Scrappy cartoon, the old horse is bound for a retirement stable, named “The End of the Trail”. His old pumper wagon is going too, with the Professor charged with the responsibility of seeing to it, sitting in its driver’s seat. “Everything goes but the badge”, says the Captain, removing the shiny number “1″ from the front of the fire horse’s hat, and hanging it upon the radiator of the new engine. The horse weeps, and the Professor controls the reins to slowly prod the horse into the long walk for “the last mile”. The Captain putters for an overly-long time, admiring his new engine, and is just trying out the driver’s seat for size, when the phone rings. It is a call from Mama at home. But it is also a business call, as Mama has somehow set the house on fire, and screams for the Captain to hurry, while black smoke clouds form behind her into humanized shape, and attempt to prevent her call by placing their “hands” over Mama’s mouth to smother her. The Captain starts to sputter, “Well, call the fire departmen….”, before realizing he is the fire department. He climbs back into the engine (with no support crew) and turns the key. As in Scrappy’s “The Fire Plug”, our chief hasn’t bothered to familiarize himself with the machinery, and after gasping and coughing, the engine kicks into gear and barrels out of the station house, with the Captain barely maintaining any control. While Mama beats at the flames with a broom, and is chased out onto the end of a second-story flagpole, where she clings with the flames tickling her rear end, the Captain tries to figure out what lever to pull to have an effect on the engine. He tries the brake handle – and yanks it loose. He finds the gearshift, but is traveling so fast, he passes right by the house as he struggles to change gear. When he finaly does, he shifts into reverse. The engine passes the house again, and rear-ends into a tree. The extension ladder is thrust forward, catching the Captain on its foremost end. The ladder expands with such force, its rungs collide with the metal framework holding the fire bell on the engine hood, so that the framework cuts away every rung of the ladder except the topmost one where the Captain is caught. Then the engine’s machinery aims the ladder straight up, leaving the Captain in the same position as Mickey Mouse and Miny – suspended about a half-dozen floors above the fire, with no visible way down.

Here, the film makes its biggest error – abandoning all hope of creative sight and prop gags, by dropping the flame entirely out of the picture, and leaving its two principal characters stranded with nowhere to go. All that is left to finish what little story there is is the Professor and the old horse. At slow and deliberate pace, smoke from the fire extends over the countryside, reaching the nostrils of the horse just as he is about to enter the gates of the retirement stable. The smoke invigorates him with renewed energy, and he even chews upon its aromas and inhales them in corkscrew curves to savor the reminder of his days of old. Giving a whinny, he breaks into a gallop, towing the Professor and the pumper wagon back down the road to the Captain’s house. The horse hooks up a hose to the water system, then manually pumps the engine mechanism, while the Professor lets the pressure build inside the hose’s nozzle end, opening it once the hose has ballooned, to put out the fire throughout the house in one massive gush. But one bit of flame is about to eat away the last support of Mama on the flagpole (shades of Tillie Tiger!). With no particular complications, the Professor and the horse position a safety net under Mama, who lands a bit hard with one bounce off the ground, but comes out okay. Meanwhile, the Captain’s shirt collar is about to rip though, making him need the net too. The horse and Professor tug to get the net out from under plump Mama – and only succeed in pulling loose the net handles, rather than the fabric trampoline in-between. Unaware of their lack of a center, the horse and Professor stand on opposite sides of the new fire engine, thinking they are providing a place for the Captain to land. The Captain falls hard upon the engine itself, driving it into a crater in the ground, just loke a Terrytoons pig. The Captain crawls his way out of the hole, then finds himself followed by the struggling engine, whose headlights and radiator now take on the features of a face. It looks up at the Captain apologetically, needing a hand to climb out of the crater. Instead, the Captain removes the number “1″ shield off the engine radiator, then kicks the vehicle back into the hole, the horse adding the final touch by kicking some dirt in on top of it with his hoofs. The Captain grabs the horse’s hat, replaces the shield upon it, and presents it to the horse, reinstating him to duty. The horse whinnies appreciatively, and licks the Captain’s face, for the iris out.

Here, the film makes its biggest error – abandoning all hope of creative sight and prop gags, by dropping the flame entirely out of the picture, and leaving its two principal characters stranded with nowhere to go. All that is left to finish what little story there is is the Professor and the old horse. At slow and deliberate pace, smoke from the fire extends over the countryside, reaching the nostrils of the horse just as he is about to enter the gates of the retirement stable. The smoke invigorates him with renewed energy, and he even chews upon its aromas and inhales them in corkscrew curves to savor the reminder of his days of old. Giving a whinny, he breaks into a gallop, towing the Professor and the pumper wagon back down the road to the Captain’s house. The horse hooks up a hose to the water system, then manually pumps the engine mechanism, while the Professor lets the pressure build inside the hose’s nozzle end, opening it once the hose has ballooned, to put out the fire throughout the house in one massive gush. But one bit of flame is about to eat away the last support of Mama on the flagpole (shades of Tillie Tiger!). With no particular complications, the Professor and the horse position a safety net under Mama, who lands a bit hard with one bounce off the ground, but comes out okay. Meanwhile, the Captain’s shirt collar is about to rip though, making him need the net too. The horse and Professor tug to get the net out from under plump Mama – and only succeed in pulling loose the net handles, rather than the fabric trampoline in-between. Unaware of their lack of a center, the horse and Professor stand on opposite sides of the new fire engine, thinking they are providing a place for the Captain to land. The Captain falls hard upon the engine itself, driving it into a crater in the ground, just loke a Terrytoons pig. The Captain crawls his way out of the hole, then finds himself followed by the struggling engine, whose headlights and radiator now take on the features of a face. It looks up at the Captain apologetically, needing a hand to climb out of the crater. Instead, the Captain removes the number “1″ shield off the engine radiator, then kicks the vehicle back into the hole, the horse adding the final touch by kicking some dirt in on top of it with his hoofs. The Captain grabs the horse’s hat, replaces the shield upon it, and presents it to the horse, reinstating him to duty. The horse whinnies appreciatively, and licks the Captain’s face, for the iris out.

A rare publicity still from the Cartoon Research Archive – “Little Moths Big Flame” (1938)

Little Moths Big Flame (Mintz/Columbia, Color Rhapsodies, 11/3/38 – Sid Marcus, dir,) A strange entry in the studio’s color output, which didn’t seem to be aimed at the kiddies, but was more fraught with innuendo for the adults, with sugar coating for those youngsters who happened to be in the theater seats. This unusual choice of target audience cost the film a berth in the revivals of Columbia cartoons for the “Totally Tooned In” syndication, where it was passed over for inclusion.

Presumably inspired by Disney’s “Moth and the Flame”, the film takes a quite different approach than Disney. Although both are to some degree stories of seduction, the Disney film kept things at the level of mere flirtation on the part of the female, who seems to remain largely in control of the situation, and knows when to ditch herself of a suitor who tries to go too far. Giving their heroine a little moxie in such manner served to keep Disney’s product squeaky-clean for the kiddies, in the manner of a straight adventure rather than a scandalous affair. Columbia, however, presents a female who is too cutesie for words, overly gullible, and not at all in control of her destiny or her own emotions – easy prey for the wicked wiles of a seducer. The result becomes almost an exploitation film reduced to cartoon form, presenting a moralistic melodramatic tale of a girl gone wrong.

Presumably inspired by Disney’s “Moth and the Flame”, the film takes a quite different approach than Disney. Although both are to some degree stories of seduction, the Disney film kept things at the level of mere flirtation on the part of the female, who seems to remain largely in control of the situation, and knows when to ditch herself of a suitor who tries to go too far. Giving their heroine a little moxie in such manner served to keep Disney’s product squeaky-clean for the kiddies, in the manner of a straight adventure rather than a scandalous affair. Columbia, however, presents a female who is too cutesie for words, overly gullible, and not at all in control of her destiny or her own emotions – easy prey for the wicked wiles of a seducer. The result becomes almost an exploitation film reduced to cartoon form, presenting a moralistic melodramatic tale of a girl gone wrong.

The moth (bearing no resemblance to human form except in structure of arms and legs, and instead drawn in toony “bug” circular style, flutters around a lit window of a house at night, inside of which is a kerosene lantern, and within its glass, a flame (depicted in a single shade of dark red, free-walking rather than dependent upon a wick, and more akin in looks to a devil with fanged teeth rather than a fire). The flame beckons her to “Come in and see my paintings” (suggesting the “Etchings” line traditionally associated with cads as a come-on). Too shy for words, the moth blushes, and hides her face behind a portion of the window frame. The flame slips inside the metal base of the kerosene lamp from which his fire emits, and disappears from view, leaving the room darkened. The girl remains intrigued, and seeing the window slightly ajar at the top, slips inside, then into the glass of the lamp, to investigate and peer down into the metal base. There, she finds a fully-furnished bachelor apartment, where the flame lounges in various positions upon a sofa. The moth enters, barely able to look the camera in the eye, as she descends a staircase to the living room, bashful at being in a man’s apartment. (However, this didn’t stop her from briefly applying powder to her face before entering.) The flame bids her welcome, and places a comfortable pillow close to him on the sofa, inviting her to sit down. Trying to maintain her etiquette, the moth tiptoes over to the opposite end of the sofa, taking a seat as far away from him as she can, and still covering her face to mask her embarrassment. The flame, however, comes equipped for such situations, and pulls a lever on his end of the sofa – compressing the furnishing into a cozy love-seat for two. (Tex Avery would later install similar equipment in the front passenger seat of his “Car of Tomorrow” at MGM.) The moth is startled and screams, and a chase begins around and around the coffee table. The flame stumbles over the obstacle, but the moth is soon cornered in an easy chair. The flame does not yet attack, but tries to place her in a willing mood. “Cigarette”, he offers? ”No, thank you”, replies the girl in a whispery voice, too polite to even speak up for herself at the flame’s previous behavior. “Drink?” offers the flame, pouring out a glass of champagne. Again “No, thank you” – then the girl adds in her weak-hearted juvenile way, “I think I’d better go.

The moth (bearing no resemblance to human form except in structure of arms and legs, and instead drawn in toony “bug” circular style, flutters around a lit window of a house at night, inside of which is a kerosene lantern, and within its glass, a flame (depicted in a single shade of dark red, free-walking rather than dependent upon a wick, and more akin in looks to a devil with fanged teeth rather than a fire). The flame beckons her to “Come in and see my paintings” (suggesting the “Etchings” line traditionally associated with cads as a come-on). Too shy for words, the moth blushes, and hides her face behind a portion of the window frame. The flame slips inside the metal base of the kerosene lamp from which his fire emits, and disappears from view, leaving the room darkened. The girl remains intrigued, and seeing the window slightly ajar at the top, slips inside, then into the glass of the lamp, to investigate and peer down into the metal base. There, she finds a fully-furnished bachelor apartment, where the flame lounges in various positions upon a sofa. The moth enters, barely able to look the camera in the eye, as she descends a staircase to the living room, bashful at being in a man’s apartment. (However, this didn’t stop her from briefly applying powder to her face before entering.) The flame bids her welcome, and places a comfortable pillow close to him on the sofa, inviting her to sit down. Trying to maintain her etiquette, the moth tiptoes over to the opposite end of the sofa, taking a seat as far away from him as she can, and still covering her face to mask her embarrassment. The flame, however, comes equipped for such situations, and pulls a lever on his end of the sofa – compressing the furnishing into a cozy love-seat for two. (Tex Avery would later install similar equipment in the front passenger seat of his “Car of Tomorrow” at MGM.) The moth is startled and screams, and a chase begins around and around the coffee table. The flame stumbles over the obstacle, but the moth is soon cornered in an easy chair. The flame does not yet attack, but tries to place her in a willing mood. “Cigarette”, he offers? ”No, thank you”, replies the girl in a whispery voice, too polite to even speak up for herself at the flame’s previous behavior. “Drink?” offers the flame, pouring out a glass of champagne. Again “No, thank you” – then the girl adds in her weak-hearted juvenile way, “I think I’d better go.

I told Mama I’d be home early.” She climbs out of the chair, and daintily tiptoes her way back to the stairs, in a mood half of fear, half of shame. The flame resorts to never-fail charm number 3 – converting a portion of his fire into the form of a flaming red violin and bow, and luring her with a gypsy serenade. At the sound of the music, the girl stops in her tracks, then turns around, attempting to conceal a smile that is spread coyly across her face. He has found her weakness. Under the spell of the music, the girl begins to flit about like a ballerina, then begins to spin – until the whole room seems to be spinning around her – faster, and faster still. The violin music reaches a crescendo – them the flame lowers the violin entirely, while the girl continues in her dizzy spin. In a move startling for its suddenness, obviously intended to depict the sudden fall into loss of innocence, the flame grabs hold of both of the girl’s outstretched wings – and burns them in a heartbeat to mere charred outlines of their former dimensions, the background color transforming into somber, darkened shade as the burning is completed. The girl stands in shock, and pathetically whimpers, as the flame laughs in evil triumph, and the scene fades to black.

I told Mama I’d be home early.” She climbs out of the chair, and daintily tiptoes her way back to the stairs, in a mood half of fear, half of shame. The flame resorts to never-fail charm number 3 – converting a portion of his fire into the form of a flaming red violin and bow, and luring her with a gypsy serenade. At the sound of the music, the girl stops in her tracks, then turns around, attempting to conceal a smile that is spread coyly across her face. He has found her weakness. Under the spell of the music, the girl begins to flit about like a ballerina, then begins to spin – until the whole room seems to be spinning around her – faster, and faster still. The violin music reaches a crescendo – them the flame lowers the violin entirely, while the girl continues in her dizzy spin. In a move startling for its suddenness, obviously intended to depict the sudden fall into loss of innocence, the flame grabs hold of both of the girl’s outstretched wings – and burns them in a heartbeat to mere charred outlines of their former dimensions, the background color transforming into somber, darkened shade as the burning is completed. The girl stands in shock, and pathetically whimpers, as the flame laughs in evil triumph, and the scene fades to black.

Our story resumes at the crack of dawn, with the rooster crowing along a country road. He looks down and ceases his crowing – instead letting out a whistle at the sight he sees. The weary moth is dragging herself home by foot, unable to fly, and is at the point of near-exhaustion. She weeps bitterly, while an unseen male barbershop chorus sings a melodramatic gay-nineties style song bemoaning her plight, much in the vein of “She Is More To Be Pitied Than Censured.” As she passes a pair of heavily-patched trousers in a farmhouse, the parches roll down like windows, as two old-spinster moths observe her and begin gossiping, “Her wings are burnt.” “No!” Finally collapsing outside another old garment which is her home, the moth wails pathetically for her “Mama!” A father and mother moth answer the call, with father complaining about the improperness of coming home at this hour. Mother is first to discover the burnt wings, and wails, “My poor daughter”, while an outraged Papa demands to know “Who did it?” “The Flame”, weeps the moth. The name of the accused sweeps through the moth community like wildfire, upon everybody’s tongue, until an outraged mob forms, and masses to seek vengeance against the offending fiend. Various mob-style objects for inflicting a beating are carried by the populace, along with a small vat of bubbling tar, and a sack of feathers.

Our story resumes at the crack of dawn, with the rooster crowing along a country road. He looks down and ceases his crowing – instead letting out a whistle at the sight he sees. The weary moth is dragging herself home by foot, unable to fly, and is at the point of near-exhaustion. She weeps bitterly, while an unseen male barbershop chorus sings a melodramatic gay-nineties style song bemoaning her plight, much in the vein of “She Is More To Be Pitied Than Censured.” As she passes a pair of heavily-patched trousers in a farmhouse, the parches roll down like windows, as two old-spinster moths observe her and begin gossiping, “Her wings are burnt.” “No!” Finally collapsing outside another old garment which is her home, the moth wails pathetically for her “Mama!” A father and mother moth answer the call, with father complaining about the improperness of coming home at this hour. Mother is first to discover the burnt wings, and wails, “My poor daughter”, while an outraged Papa demands to know “Who did it?” “The Flame”, weeps the moth. The name of the accused sweeps through the moth community like wildfire, upon everybody’s tongue, until an outraged mob forms, and masses to seek vengeance against the offending fiend. Various mob-style objects for inflicting a beating are carried by the populace, along with a small vat of bubbling tar, and a sack of feathers.

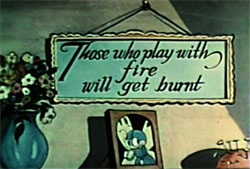

Back at the lamp, the flame seems to be thoroughly enjoying himself in the incongruous setting of a bathtub – seemingly impossible, until we discover the shower is provided from a can of kerosene. There is a knock at the door. Transforming a portion of himself into the shape of a Britisher’s monocle, the flame feigns the voice of an Englishman, telling whoever is outside that he’s in the “bawth” and does not wish to be disturbed. On the other side of the door is Papa, with the mob grouped upon the staircase of the apartment. At a signal, the moths hit the bathroom door like a battering ram, breaking it down. The apartment walls begin to vibrate with the shock waves of an unseen battle within. (One can only wonder what the moths are hitting him with that don’t burn.) A shot from outside the lamp shows the flame trying to escape out the top, but somehow being dragged back in. (How again do the moths do this without being burned themselves?) Once he is back inside the lamp base, the moths emerge from its hole, then pour in the bubbling tar, followed by the sack of feathers – then finally plant a gravestone into the tarred hole, and sprinkle a few flower seeds upon the makeshift grave, which spring up to the tune of the Funeral March. For all their efforts, the flame doesn’t seem to be punished enough to suit the crime, as a last shot inside the apartment reveals him still apparently in one piece (even sealing up the lamp doesn’t snuff him out), covered in tar and attempting to blow away feathers stuck to his face. Seems like he got off lightly. The final shot shows the improbable result of Mama sewing for daughter a new pair of silk wings, stitch bu stitch over an outline framework, while the moth acts like a total juvenile infant, contentedly licking at a lollipop! (If only losses of innocence could be cured so easily in real life.) The camera pans up to a sampler on the wall, providing the obvious moral, “Those who play with fire will get burnt.”

Back at the lamp, the flame seems to be thoroughly enjoying himself in the incongruous setting of a bathtub – seemingly impossible, until we discover the shower is provided from a can of kerosene. There is a knock at the door. Transforming a portion of himself into the shape of a Britisher’s monocle, the flame feigns the voice of an Englishman, telling whoever is outside that he’s in the “bawth” and does not wish to be disturbed. On the other side of the door is Papa, with the mob grouped upon the staircase of the apartment. At a signal, the moths hit the bathroom door like a battering ram, breaking it down. The apartment walls begin to vibrate with the shock waves of an unseen battle within. (One can only wonder what the moths are hitting him with that don’t burn.) A shot from outside the lamp shows the flame trying to escape out the top, but somehow being dragged back in. (How again do the moths do this without being burned themselves?) Once he is back inside the lamp base, the moths emerge from its hole, then pour in the bubbling tar, followed by the sack of feathers – then finally plant a gravestone into the tarred hole, and sprinkle a few flower seeds upon the makeshift grave, which spring up to the tune of the Funeral March. For all their efforts, the flame doesn’t seem to be punished enough to suit the crime, as a last shot inside the apartment reveals him still apparently in one piece (even sealing up the lamp doesn’t snuff him out), covered in tar and attempting to blow away feathers stuck to his face. Seems like he got off lightly. The final shot shows the improbable result of Mama sewing for daughter a new pair of silk wings, stitch bu stitch over an outline framework, while the moth acts like a total juvenile infant, contentedly licking at a lollipop! (If only losses of innocence could be cured so easily in real life.) The camera pans up to a sampler on the wall, providing the obvious moral, “Those who play with fire will get burnt.”

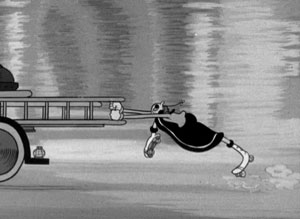

A Date to Skate (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 11/18/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Orestes Calpini, anim.) – Only trouble can occur when Popeye coaxes the gangly Olive Oyl into spending the afternoon in a roller-skating rink – although she doesn’t know the first thing about skating. The idea wasn’t new – Fleischer himself had placed Olive on ice skates in Popeye’s first year, for the Christmas special “Seasons Greetinks”. But setting it amidst the urban sprawl of the big city provides opportunity for a wide variety of new twists. A memorable scene has Olive faced with the difficult question of “What size?” from the attendant at the skate rental booth at the main entrance. “I take a 3 1/2 but an 8 feels so good”, replies Olive. Popeye, referring to her under his breath as a “Flat Foot Floogee”, adds the sum and suggests a 12. Olive’s pratfalls take up most of the cartoon, but eventually, her out-of-control antics roll into the city streets, and amidst crosstown traffic. She both enters and exits a crowded department store, then finally reaches a moment of peace where she appears to be standing still in the street. She attempts to slide over to a nearby lamp post to lean on and rest – but finds no relaxation, as a fast-moving fire engine slips between Olive and the curb, with Olove mistakenly grabbing on to the rear ladder instead of the lamp. The engine careens through the streets, with Olive’s long legs attempting mile-long strides to keep up. Popeye, who has been unsuccessfully pursuing her, reaches into his pocket for his old standby – but finds his pockets empty. “Now, don’t tell me I’m gettin’ old”, remarks Popeye at his own forgetfulness, then resorts to seeking outside help, calling to the theater audience, “Is there any spinach in the house?” “Here y’are, Popeye”, shouts back the silhouette of an attendee in the audience, who tosses a can into the screen. (Seems as though the writers had been watching some old Tex Avery episodes.) Popeye takes off, over the top of traffic, and down a long hill of divided highways and criss-crossing bridges and lanes to keep up with Olive, and finally catches up with her at the loop of a rotary. “Are ya hurt?” asks Popeye. Olive, who is just beginning to like the sport, responds, “Let’s do it again!”

A Date to Skate (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 11/18/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Orestes Calpini, anim.) – Only trouble can occur when Popeye coaxes the gangly Olive Oyl into spending the afternoon in a roller-skating rink – although she doesn’t know the first thing about skating. The idea wasn’t new – Fleischer himself had placed Olive on ice skates in Popeye’s first year, for the Christmas special “Seasons Greetinks”. But setting it amidst the urban sprawl of the big city provides opportunity for a wide variety of new twists. A memorable scene has Olive faced with the difficult question of “What size?” from the attendant at the skate rental booth at the main entrance. “I take a 3 1/2 but an 8 feels so good”, replies Olive. Popeye, referring to her under his breath as a “Flat Foot Floogee”, adds the sum and suggests a 12. Olive’s pratfalls take up most of the cartoon, but eventually, her out-of-control antics roll into the city streets, and amidst crosstown traffic. She both enters and exits a crowded department store, then finally reaches a moment of peace where she appears to be standing still in the street. She attempts to slide over to a nearby lamp post to lean on and rest – but finds no relaxation, as a fast-moving fire engine slips between Olive and the curb, with Olove mistakenly grabbing on to the rear ladder instead of the lamp. The engine careens through the streets, with Olive’s long legs attempting mile-long strides to keep up. Popeye, who has been unsuccessfully pursuing her, reaches into his pocket for his old standby – but finds his pockets empty. “Now, don’t tell me I’m gettin’ old”, remarks Popeye at his own forgetfulness, then resorts to seeking outside help, calling to the theater audience, “Is there any spinach in the house?” “Here y’are, Popeye”, shouts back the silhouette of an attendee in the audience, who tosses a can into the screen. (Seems as though the writers had been watching some old Tex Avery episodes.) Popeye takes off, over the top of traffic, and down a long hill of divided highways and criss-crossing bridges and lanes to keep up with Olive, and finally catches up with her at the loop of a rotary. “Are ya hurt?” asks Popeye. Olive, who is just beginning to like the sport, responds, “Let’s do it again!”

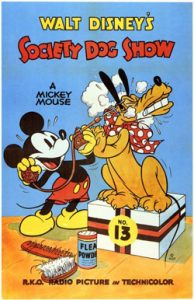

Society Dog Show (Disney, RKO, Mickey Mouse, 2/3/39 – Bill Roberts, dir.) – provides Disney with yet another chance for spectacle. An elite dog show brings out the upper crust of the town to enter their prize pooches – and the riff raff, in the form of Mickey Mouse and Pluto, who arrive in a wooden scooter just one step above a soap box derby racer, using roller skates as wheels. (How did they ever obtain an entry form?) Inside, Mickey attempts to compete with the best of the highbrows in dog grooming, with a roll-out all purpose kit of every brush and polisher known to man, applying combing, perfume, and even shoe polish to Pluto (the latter to make his nose shine). While Mickey attempts to retrieve one item which has rolled below the stage curtains, Pluto strikes up a romantic interest with Fifi (the cocker spaniel usually owned by Minnie in the day, though she is nowhere to be seen in this picture). A call rings out for entry number 13 to report to the judge’s stand. “That’s us”, responds the returning Mickey. He instructs Pluto to turn on the class, and leads him to the reviewing platform. “Why of all the….Is this a dog?”, remarks the pompous judge. Mickey tries to tout Pluto’s good points, but the judge is less than impressed with Pluto’s off-balance point, drooping ears, and wagging tail in the judge’s face. When the judge finally declares him a “mutt”, Pluto snarls, and chases the judge up his own microphone stand. “Throw him out! Throw him out!”, bellows the judge’s voice over the loudspeakers. Ushers rush in, and give Mickey and Pluto the boot, downstairs and back onto the street next to their soap-box scooter. “Don’t worry, Pluto. You’re a better dog than all of ‘em”, Mickey consoles his pet.

Society Dog Show (Disney, RKO, Mickey Mouse, 2/3/39 – Bill Roberts, dir.) – provides Disney with yet another chance for spectacle. An elite dog show brings out the upper crust of the town to enter their prize pooches – and the riff raff, in the form of Mickey Mouse and Pluto, who arrive in a wooden scooter just one step above a soap box derby racer, using roller skates as wheels. (How did they ever obtain an entry form?) Inside, Mickey attempts to compete with the best of the highbrows in dog grooming, with a roll-out all purpose kit of every brush and polisher known to man, applying combing, perfume, and even shoe polish to Pluto (the latter to make his nose shine). While Mickey attempts to retrieve one item which has rolled below the stage curtains, Pluto strikes up a romantic interest with Fifi (the cocker spaniel usually owned by Minnie in the day, though she is nowhere to be seen in this picture). A call rings out for entry number 13 to report to the judge’s stand. “That’s us”, responds the returning Mickey. He instructs Pluto to turn on the class, and leads him to the reviewing platform. “Why of all the….Is this a dog?”, remarks the pompous judge. Mickey tries to tout Pluto’s good points, but the judge is less than impressed with Pluto’s off-balance point, drooping ears, and wagging tail in the judge’s face. When the judge finally declares him a “mutt”, Pluto snarls, and chases the judge up his own microphone stand. “Throw him out! Throw him out!”, bellows the judge’s voice over the loudspeakers. Ushers rush in, and give Mickey and Pluto the boot, downstairs and back onto the street next to their soap-box scooter. “Don’t worry, Pluto. You’re a better dog than all of ‘em”, Mickey consoles his pet.

Then, a new opportunity for competition arises, as the loudspeakers anounce the final event – an exhibition of world-famous trick dogs. “You’re a trick dog”, Mickey remarks to Pluto – then lays eyes upon the roller skates fastened to his scooter – “A trick skating dog!” Mickey grabs hold of Pluto by the tail, and begins tying the skates onto his paws. Inside, an array of balancing, juggling, and dancing dogs poses for a group photo for the papers. Fifi is among them, balanced on top of a large beach ball. “Hold it”, shouts the photographer – but ignites too much flash powder, in close proximity to the curtains above the stage. Poof – the curtains ignite in fast-spreading flame. All the trick dogs scamper in all directions, one knocking Fifi off her ball. Fifi falls sprawled onto the stage, as the microphone stand topples atop her back, pinning her to the floor. Outside, Mickey, unaware of the goings on, pushes Pluto toward the staircase on his new wheels. “Pluto, the Skating Marvel”, Mickey decrees as his new billing. Suddenly, a stampede of dogs, their owners, and the judge himself, stream past our heroes, fleeing to escape the fire. But one has not escaped, as the barks of Fifi are still heard from the stage. Instinctively, Pluto abandons all fear, and despite his awkwardness with the skates tied on his feet, scrambles his way up the stairs, evading the efforts of Mickey to hold him back. Mickey attempts to follow, but burning beams of the building fall from the fast-moving fire, blocking the staircase. Pluto’s on his own, as he rolls into the lobby, and collides head-first with a column hidden by the smoke. A large section of flooring begins to burn out from below, and collapses from under Pluto’s feet, leaving the dog clinging by the roller wheels on his forward paws to the remaining boards of the floor. A lick of flame upon his tail gives Pluto the boost he needs to jump back to the lobby level. There, he rolls closer to an outer wall, which also begins to collapse. Frank Tashlin’s salute to Buster Keaton is revisited, as the wall crashes down around Pluto, neatly framing Pluto in its one window frame to avoid crushing him, and continues in its fall down into the basement, taking away the lobby flooring with it, and leaving Pluto trapped atop a single square of floorboard, supported by only one wooden beam from below. The beam also burns through, snaps, and collapses, tossing Pluto off to one side.

Then, a new opportunity for competition arises, as the loudspeakers anounce the final event – an exhibition of world-famous trick dogs. “You’re a trick dog”, Mickey remarks to Pluto – then lays eyes upon the roller skates fastened to his scooter – “A trick skating dog!” Mickey grabs hold of Pluto by the tail, and begins tying the skates onto his paws. Inside, an array of balancing, juggling, and dancing dogs poses for a group photo for the papers. Fifi is among them, balanced on top of a large beach ball. “Hold it”, shouts the photographer – but ignites too much flash powder, in close proximity to the curtains above the stage. Poof – the curtains ignite in fast-spreading flame. All the trick dogs scamper in all directions, one knocking Fifi off her ball. Fifi falls sprawled onto the stage, as the microphone stand topples atop her back, pinning her to the floor. Outside, Mickey, unaware of the goings on, pushes Pluto toward the staircase on his new wheels. “Pluto, the Skating Marvel”, Mickey decrees as his new billing. Suddenly, a stampede of dogs, their owners, and the judge himself, stream past our heroes, fleeing to escape the fire. But one has not escaped, as the barks of Fifi are still heard from the stage. Instinctively, Pluto abandons all fear, and despite his awkwardness with the skates tied on his feet, scrambles his way up the stairs, evading the efforts of Mickey to hold him back. Mickey attempts to follow, but burning beams of the building fall from the fast-moving fire, blocking the staircase. Pluto’s on his own, as he rolls into the lobby, and collides head-first with a column hidden by the smoke. A large section of flooring begins to burn out from below, and collapses from under Pluto’s feet, leaving the dog clinging by the roller wheels on his forward paws to the remaining boards of the floor. A lick of flame upon his tail gives Pluto the boost he needs to jump back to the lobby level. There, he rolls closer to an outer wall, which also begins to collapse. Frank Tashlin’s salute to Buster Keaton is revisited, as the wall crashes down around Pluto, neatly framing Pluto in its one window frame to avoid crushing him, and continues in its fall down into the basement, taking away the lobby flooring with it, and leaving Pluto trapped atop a single square of floorboard, supported by only one wooden beam from below. The beam also burns through, snaps, and collapses, tossing Pluto off to one side.

Pluto lands upon two parallel cross-beams with no floor remaining above them to support, straddling them with both left skates on one beam and both right skates on the other, producing the effect of riding the tracks of a roller coaster. The crossbeams are becoming well bent by the collapsing of supports all around them, and Pluto is in for the fastest, wildest ride pf his life, as he careens across the hall in rises and falls amidst the threatening flames. The crossbeams fortunately lead directly to the stage, where Fifi remains trapped on a single square of flooring that is also about to give way. In the nick of time, Pluto intersects her path, grabbing her by the collar just as the floor disappears underneath her. Pluto and Fifi continue on their wild coaster ride, which gets wilder as the two crossbeams are reduced to one, Pluto balancing desperately to keep atop his skates. A board of the crossbeam starts to sever atop a vertical beam from below, placing Pluto in a game of teeter-totter, rolling up to the edge of the board as the crossbeam tips downward, then over its top for a jump to the next section of crossbeam. Finally, Pluto and Fifi crash through an upper story window, land upon a drain pipe, and ride it to the ground as it collapses under their weight, folding in sections to compress itself to earth below. Mickey, the judge, and the crowd converge on the dogs to see if they’re okay, and the judge reaches into his pocket for a special medal to present to Pluto – reading “Public Hero No. 1″. The medal is so big, it drags Pluto’s head down under its weight, and Pluto has to crane his neck just to read it. Fifi sidles up appreciatively, and Pluto extends an ear to draw her close to him behind the medal, where they presumably exchange some affectionate smooching, for the iris out.

Pluto lands upon two parallel cross-beams with no floor remaining above them to support, straddling them with both left skates on one beam and both right skates on the other, producing the effect of riding the tracks of a roller coaster. The crossbeams are becoming well bent by the collapsing of supports all around them, and Pluto is in for the fastest, wildest ride pf his life, as he careens across the hall in rises and falls amidst the threatening flames. The crossbeams fortunately lead directly to the stage, where Fifi remains trapped on a single square of flooring that is also about to give way. In the nick of time, Pluto intersects her path, grabbing her by the collar just as the floor disappears underneath her. Pluto and Fifi continue on their wild coaster ride, which gets wilder as the two crossbeams are reduced to one, Pluto balancing desperately to keep atop his skates. A board of the crossbeam starts to sever atop a vertical beam from below, placing Pluto in a game of teeter-totter, rolling up to the edge of the board as the crossbeam tips downward, then over its top for a jump to the next section of crossbeam. Finally, Pluto and Fifi crash through an upper story window, land upon a drain pipe, and ride it to the ground as it collapses under their weight, folding in sections to compress itself to earth below. Mickey, the judge, and the crowd converge on the dogs to see if they’re okay, and the judge reaches into his pocket for a special medal to present to Pluto – reading “Public Hero No. 1″. The medal is so big, it drags Pluto’s head down under its weight, and Pluto has to crane his neck just to read it. Fifi sidles up appreciatively, and Pluto extends an ear to draw her close to him behind the medal, where they presumably exchange some affectionate smooching, for the iris out.

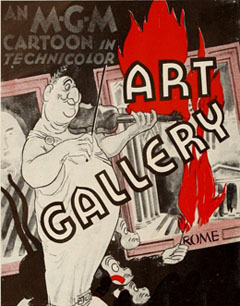

Art Gallery (MGM, 5/13/39 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – The “good little monkeys” once again return for another round of temptation – this time in what would be their final, and perhaps most egregious offense, as they are induced to commit arson by a museum statue of Nero, who comes to life at midnight, and wants to indulge his pyromania by burning a painting of Rome. Although punctuated with some clever and surreal sight gags, it’s a pretty horrendous concept – which some stations refused to show, for good reason. The monkeys enter a still-life painting of a matchbook, lighters, and ash trays, but, despite their adventures in smoking in their previous episode, are clueless how to use them. That is, until they begin to consume from the nozzle of a can of lighter fluid (99 and 44/100’s percent alcohol). Not only do the three monks become thoroughly soused, but as one hiccups, a flame pops out of his open mouth, like a living lighter. Nero shouts words of encouragement, as the lighter-monkey is propped upon the shoulders of another, while the third monkey shoots sprays of fluid from the can through the fire, and over across the hall to the painting of Rome. Nero gets his wish, and the painting erupts in flames. In creepy, fire-lit relief, Nero appears in close-up, shouting in victory to the audience, “I’M BURNING ROME!” The fire quickly spreads to other paintings as well, presenting opportunity for some of the best sight gags. A picture of Mammoth Cave morphs into the open moth of Joe E. Brown for his signature yell, “Hey – y – y – Y – Y!” An Egyptian “siren” transforms into the wailing fire variety. Mrs. O’Leary’s turf is explored again, as a fire engine careens through a painting marked “Old Chicago”. A string of portraits of the English royalty of Henrys screams for help, the last portrait depicting a Model T, marked “Henry 8″. Whistler’s Mother turns into a human steam whistle. Alexander Wolcott, as the town cryer, rings an alarm bell and monotones “Hear ye, Hear ye.” The monkeys begin running from one painting into another and another, one step ahead of the forward edge of the firestorm. They pass through a painting of a cornfield, where all the ears are transformed into popcorn. A painting of a sheep dog becomes a hot dog. The Three Musketeers are somehow reduced by the flame to Groucho, Harpo, and Chico Marx. Three flying cherubs become three black babies singing “Swanee River’. The monkeys manage to escape by diving in a stream in one painting, then coming up from the canals of Venice in another, from which they hop out onto their own pedestal to resume their standard poses (with one hiccup of flame from the one in the middle). Oddly, the last shot shows no sign of the fire or damage at all, as the sun rises outside the museum window, and Nero is forced to freeze into rigid position for the day ahead. Was it all a figment of the statue’s imagination? Or of ours? Certainly not the latter – none of us would have concocted a cartoon this weird.

Art Gallery (MGM, 5/13/39 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – The “good little monkeys” once again return for another round of temptation – this time in what would be their final, and perhaps most egregious offense, as they are induced to commit arson by a museum statue of Nero, who comes to life at midnight, and wants to indulge his pyromania by burning a painting of Rome. Although punctuated with some clever and surreal sight gags, it’s a pretty horrendous concept – which some stations refused to show, for good reason. The monkeys enter a still-life painting of a matchbook, lighters, and ash trays, but, despite their adventures in smoking in their previous episode, are clueless how to use them. That is, until they begin to consume from the nozzle of a can of lighter fluid (99 and 44/100’s percent alcohol). Not only do the three monks become thoroughly soused, but as one hiccups, a flame pops out of his open mouth, like a living lighter. Nero shouts words of encouragement, as the lighter-monkey is propped upon the shoulders of another, while the third monkey shoots sprays of fluid from the can through the fire, and over across the hall to the painting of Rome. Nero gets his wish, and the painting erupts in flames. In creepy, fire-lit relief, Nero appears in close-up, shouting in victory to the audience, “I’M BURNING ROME!” The fire quickly spreads to other paintings as well, presenting opportunity for some of the best sight gags. A picture of Mammoth Cave morphs into the open moth of Joe E. Brown for his signature yell, “Hey – y – y – Y – Y!” An Egyptian “siren” transforms into the wailing fire variety. Mrs. O’Leary’s turf is explored again, as a fire engine careens through a painting marked “Old Chicago”. A string of portraits of the English royalty of Henrys screams for help, the last portrait depicting a Model T, marked “Henry 8″. Whistler’s Mother turns into a human steam whistle. Alexander Wolcott, as the town cryer, rings an alarm bell and monotones “Hear ye, Hear ye.” The monkeys begin running from one painting into another and another, one step ahead of the forward edge of the firestorm. They pass through a painting of a cornfield, where all the ears are transformed into popcorn. A painting of a sheep dog becomes a hot dog. The Three Musketeers are somehow reduced by the flame to Groucho, Harpo, and Chico Marx. Three flying cherubs become three black babies singing “Swanee River’. The monkeys manage to escape by diving in a stream in one painting, then coming up from the canals of Venice in another, from which they hop out onto their own pedestal to resume their standard poses (with one hiccup of flame from the one in the middle). Oddly, the last shot shows no sign of the fire or damage at all, as the sun rises outside the museum window, and Nero is forced to freeze into rigid position for the day ahead. Was it all a figment of the statue’s imagination? Or of ours? Certainly not the latter – none of us would have concocted a cartoon this weird.

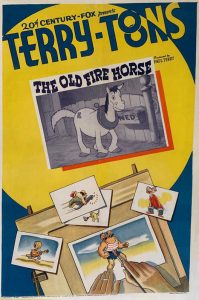

The Old Fire Horse (Terrytoons/Fox, 7/26/39 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.), is considered a “lost” film, having not been included in the CBS manifest (though its elements probably exist at UCLA). However, it is one of those films not censored for content, but simply not used because it was considered to be too close in content to a Technicolor redrawing later issued on 5/25/44, entitled “Smoky Joe” (oddly, crediting Connie Rasinski as director instead of Donnelly), likely using most of the same animation, which continues to have a 1930’s feel. We’ll thus review the color version in its place, out of chronological sequence.

The Old Fire Horse (Terrytoons/Fox, 7/26/39 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.), is considered a “lost” film, having not been included in the CBS manifest (though its elements probably exist at UCLA). However, it is one of those films not censored for content, but simply not used because it was considered to be too close in content to a Technicolor redrawing later issued on 5/25/44, entitled “Smoky Joe” (oddly, crediting Connie Rasinski as director instead of Donnelly), likely using most of the same animation, which continues to have a 1930’s feel. We’ll thus review the color version in its place, out of chronological sequence.

We meet Smoky in an old fire house, as a narrator asks “Just how old are you, Joe?” The horse begins to stamp out the number in taps of his hoof, several times, ending with a rapid “Shave and a haircut” beat. “What?” asks the narrator. Joe throws in the extra “two bits” in two beats, and the narrator responds “Uhh huh.” A telegram arrives for the human fire chief and crew, as usual announcing a new fire truck is coming – “GET RID OF THE HORSE”. The chief and crew celebrate, by picking up a banjo, and strutting around the station house, singing a ditty about “We won’t need the horse any more.” “What are you going to do about it?”, the narrator asks Joe. Vengeful, Joe triggers off the fire alarm, leaps into harness, and takes the responding fire fighters “for a ride”, over hill, down dale, zig zagging through trees, then back to the station with a wild sharp turn at the end, tossing the firemen off the wagon and into the mud of a pig sty. He gives them a horse laugh, back in the comfort of his stall.

The new pumper engine arrives right on schedule, with the fire crew riding it through the town in a parade. Joe, however, is waiting at the door of the station, armed with a fire shovel, and swings it back and forth in threatening manner to keep the engine from entering the station, then shuts himself inside the station and hods the doors shit. The chief and crew decide to break down the door with the truck, then give Joe the bum’s rush, with instruction to leave town. But Joe has other ideas. The narrator observes that Joe had saved his money (I didn’t even know fire horses got pay), and buys a home right next door to the station. The chief has to pass his door each morning, and despite wishing Joe a cordial “Good morning”, is spit at by the frustrated steed. In moments when the engine remains unattended, Joe, slips into the station house, and delivers a kick or two to the engine’s bumper. He receives a surprise, however, when the engine’s headlights and bumper form into a face, and address him verbally, taking the kicks in stride. “You’re all through, Joe”, says the engine. Startled, Joe rushes back to his home porch, as the returning chief rushes past the door to avoid another expectoration.

The new pumper engine arrives right on schedule, with the fire crew riding it through the town in a parade. Joe, however, is waiting at the door of the station, armed with a fire shovel, and swings it back and forth in threatening manner to keep the engine from entering the station, then shuts himself inside the station and hods the doors shit. The chief and crew decide to break down the door with the truck, then give Joe the bum’s rush, with instruction to leave town. But Joe has other ideas. The narrator observes that Joe had saved his money (I didn’t even know fire horses got pay), and buys a home right next door to the station. The chief has to pass his door each morning, and despite wishing Joe a cordial “Good morning”, is spit at by the frustrated steed. In moments when the engine remains unattended, Joe, slips into the station house, and delivers a kick or two to the engine’s bumper. He receives a surprise, however, when the engine’s headlights and bumper form into a face, and address him verbally, taking the kicks in stride. “You’re all through, Joe”, says the engine. Startled, Joe rushes back to his home porch, as the returning chief rushes past the door to avoid another expectoration.

Finally, a fire alarm is received. The engine company takes off – and so does Joe, carrying a fire hose wrapped around his neck, a long ladder, and assorted pails and axes. For a change this time, the mechanical engine is not mishandled by the fire fighters, but appears to break down of its own power – first suffering a flat tire (causing the firemen to carry one corner of the vehicle along on foot), then having most of its body work fall apart. (Where’s the warranty on this thing? I smell a lawsuit.) Joe approaches on the same road, and the firemen extend their thumbs to hitch a ride. But Joe races on right past them, leaving the firemen to race on foot to catch him and hop on the ladder if they want transportation. The group arrive at the fire, and Joe lets the crew unspool the hose from his neck and hook it up to the hydrant, while Joe mans the nozzle end, being shot into the air by the water pressure up to the roof, where he hooks the nozzle over the top of the roof, to flood the fire from above. The horse drops down to a windowsill just below the roof, and pulls open the window. Like Kiko the kangaroo, a flood of the hose water emerges, and Joe has to swim against the current to get inside. As the water subsides, Joe begins battling portions of the blaze inside, while the fire chief races in from below. Joe scoops up much of the blaze by sweeping it into a dust pan, but the chief arrives, and tells him to “Drop that.” Bad move, as the fire immediately spreads on the floor, and chases the chief out the window, out onto the end of a flagpole, where he falls off and dangles by his suspenders. Joe returns to ground level, and races outside, to find the crowd watching the chief’s plight with audible gasps. Joe effects a rescue, taking two fire axes in his hoofs, and chopping hand-over-hand into the wall to use them as climbing spikes, scaling his way up the side of the building. Once on a level with the chief, he chops off the end of the flagpole, and lets the chief fall. The horse then darts into the building, rides like a child down the bannisters of the staircase, and arrives at ground level a split second ahead of the chief to make the catch. The crowd cheers, and the grateful chief, commenting, “What a horse!”, exchanges fire hats with Joe, appointing the horse new chief. The short ends with another parade, as Joe proudly struts through the town, towing the broken down-engine and crew behind.

Finally, a fire alarm is received. The engine company takes off – and so does Joe, carrying a fire hose wrapped around his neck, a long ladder, and assorted pails and axes. For a change this time, the mechanical engine is not mishandled by the fire fighters, but appears to break down of its own power – first suffering a flat tire (causing the firemen to carry one corner of the vehicle along on foot), then having most of its body work fall apart. (Where’s the warranty on this thing? I smell a lawsuit.) Joe approaches on the same road, and the firemen extend their thumbs to hitch a ride. But Joe races on right past them, leaving the firemen to race on foot to catch him and hop on the ladder if they want transportation. The group arrive at the fire, and Joe lets the crew unspool the hose from his neck and hook it up to the hydrant, while Joe mans the nozzle end, being shot into the air by the water pressure up to the roof, where he hooks the nozzle over the top of the roof, to flood the fire from above. The horse drops down to a windowsill just below the roof, and pulls open the window. Like Kiko the kangaroo, a flood of the hose water emerges, and Joe has to swim against the current to get inside. As the water subsides, Joe begins battling portions of the blaze inside, while the fire chief races in from below. Joe scoops up much of the blaze by sweeping it into a dust pan, but the chief arrives, and tells him to “Drop that.” Bad move, as the fire immediately spreads on the floor, and chases the chief out the window, out onto the end of a flagpole, where he falls off and dangles by his suspenders. Joe returns to ground level, and races outside, to find the crowd watching the chief’s plight with audible gasps. Joe effects a rescue, taking two fire axes in his hoofs, and chopping hand-over-hand into the wall to use them as climbing spikes, scaling his way up the side of the building. Once on a level with the chief, he chops off the end of the flagpole, and lets the chief fall. The horse then darts into the building, rides like a child down the bannisters of the staircase, and arrives at ground level a split second ahead of the chief to make the catch. The crowd cheers, and the grateful chief, commenting, “What a horse!”, exchanges fire hats with Joe, appointing the horse new chief. The short ends with another parade, as Joe proudly struts through the town, towing the broken down-engine and crew behind.

The Bookworm (MGM, 8/26/39, I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.), receives mention for an unusual fire sequence. In the first of three films (two at MGM, one at Warner Brothers) which Freleng would direct featuring a raven and a worm, Freleng presents a “midnight in a book store” scenario, allowing the Raven from the cover of Edgar Allen Poe’s masterpiece to offer an assist to the witches’ coven from “Macbeth” with a magic potion, needing a worm as a principal ingredient. He pursues a milquetoast young bookworm through encyclopedias and various shelves of the bookstore, the chase drawing in many classic villains from the “Chamber of Horrors” section of the store, countered by Paul Revere, the Gang Busters, various detectives and cops from the Police Gazette, Napoleon, and old soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg. The worm himself becomes cornered by the raven atop a stack of books, below which waits the trio of witches with their boiling cauldron. Enter a magazine about the Boy Scouts, whose cover opens to reveal a troop of miniature scouts, anxious to effect a rescue at the sounding of a bugle. Their shelf is opposite the table on which the bookworm is stranded atop the book stack, separated by about six feet. Grabbing an ample supply of boy scout matches (of full human size), the miniature scouts begin constructing a suspension bridge of matches to span the chasm to the table. When they are close enough, they encourage the worm to jump, catching him to the surprise of the raven. The scouts retreat with the worm back to the bookshelf, then, as the raven steps out upon the bridge to follow, ignite the matches from the opposite end. The bridge burns out from under the bird, slightly singeing his tail, and dumping him into a wastebasket below. The bird emerges, and closes with a remark from Moran and Mack’s “Two Black Crows” record routine for Columbia records (paraphrases of which would close all three of Freleng’s cartoons in this vein), declaring, “Aw, who wants a worm anyway?”

The Bookworm (MGM, 8/26/39, I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.), receives mention for an unusual fire sequence. In the first of three films (two at MGM, one at Warner Brothers) which Freleng would direct featuring a raven and a worm, Freleng presents a “midnight in a book store” scenario, allowing the Raven from the cover of Edgar Allen Poe’s masterpiece to offer an assist to the witches’ coven from “Macbeth” with a magic potion, needing a worm as a principal ingredient. He pursues a milquetoast young bookworm through encyclopedias and various shelves of the bookstore, the chase drawing in many classic villains from the “Chamber of Horrors” section of the store, countered by Paul Revere, the Gang Busters, various detectives and cops from the Police Gazette, Napoleon, and old soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg. The worm himself becomes cornered by the raven atop a stack of books, below which waits the trio of witches with their boiling cauldron. Enter a magazine about the Boy Scouts, whose cover opens to reveal a troop of miniature scouts, anxious to effect a rescue at the sounding of a bugle. Their shelf is opposite the table on which the bookworm is stranded atop the book stack, separated by about six feet. Grabbing an ample supply of boy scout matches (of full human size), the miniature scouts begin constructing a suspension bridge of matches to span the chasm to the table. When they are close enough, they encourage the worm to jump, catching him to the surprise of the raven. The scouts retreat with the worm back to the bookshelf, then, as the raven steps out upon the bridge to follow, ignite the matches from the opposite end. The bridge burns out from under the bird, slightly singeing his tail, and dumping him into a wastebasket below. The bird emerges, and closes with a remark from Moran and Mack’s “Two Black Crows” record routine for Columbia records (paraphrases of which would close all three of Freleng’s cartoons in this vein), declaring, “Aw, who wants a worm anyway?”

More such films next week, to keep things toasty.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I knew there were a lot of old cartoons on this subject, but half of these are completely new to me! Those MGM cartoons are brilliantly animated and have some good gags, but Lord, do they ever creep along.

I think the fire chief in “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow” is supposed to be a caricature of Groucho Marx, despite his Joe Penner impersonation. Also, I think Fifi is meant to be a Pekingese rather than a cocker spaniel — although if there’s any ambiguity as to her breed, she probably shouldn’t be in a dog show at all.

The cliché of the depraved roué using etchings to seduce innocent young girls originated with one Stanford White, a successful New York architect who collected etchings as a hobby. His other hobby was inviting teenage girls up to his apartment to view his etchings, where he would drug and rape them. After he was murdered by the husband of one of his conquests in 1906, details of White’s sordid personal life were endlessly hashed out in the press coverage of what was called “the trial of the century”. For a lot of men, unfortunately, the main takeaway from this was the idea that etchings were a good way to pick up girls.

The witches of Macbeth do indeed mention a worm of sorts in their famous incantation, when their recipe calls for “Adder’s fork and blind-worm’s sting.” The adder, Great Britain’s only venomous snake, has retractable fangs, which gave rise to the myth that they inject their venom through their forked tongues. As for the blindworm, it’s actually a legless lizard that has no sting at all and is perfectly harmless. Still, it’s probably for the best that the raven wasn’t sent to gather other ingredients for the witches’ cauldron such as “nose of Turk”, “Tartar’s lips”, and “liver of blaspheming Jew.”

Hope there are more surprises in store when you sound the alarm next week!

Mark Kausler mentioned to me a few months ago that Little Moth’s Big Flame was his favorite Sid Marcus story, and I can see why. It is a strangely intense and adult cartoon, one wonder how it ever got produced in the first place. I don’t think any other studio at the time would even dare try making a cartoon where the body was violated like that. The thing that gets me most about Columbia was even if they didn’t always produce the best cartoons, they were willing to try anything, particularly Sid Marcus

I should point out a small correction: Fifi is supposed to be a Pekingese according to official sources and not a Cocker Spainel like the later Miss Lady.

Ewwwwww, not Little Moth’s Big Flame. Don’t know about y’all, but while I like my cartoons weird, the stuff going on in this one is up there on the list of things I could stand not to have in my head. Then again, if the likes of The Exorcist can attain widely-held esteem, and Law & Order: SVU break records in its success, perhaps the readership can handle this, and I myself am not above discussing it either. Still, when the films start achieving novel ways of depicting child sexual abuse with the approval of notoriously prudish Catholic censors, my brain is toast.

No, really. When it comes to the scene of the moth’s reaction to the music, I’m not seeing any concealed smile on her face there, bub. Rather, an initial expression of bewilderment over being, uh, “charmed” in another, apparently more physiological way. Given this character’s evident age, I can see why. And imagine Alfred Kinsey thinking, “that Marcus fellow, I should interview him.”