This week, a holiday screen comeback for an animation pioneer, a Tex Avery laugh-fest, the debut of a world-renowned character who would cause a sort of upheaval in animation styles, a classic Disney one-shot, and a trio of Screen Songs. Not a bad mix as the first days of Fall fall upon us.

We begin with another item out of chronological sequence, overlooked last week. Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (Jam Handy, 11/11/48 – Max Fleischer, dir.), technically qualifies as a commercial film for hire, though few today tend to classify it as such. The character was the holiday invention of an employee of Montgomery Ward department stores. Robert May, who originally wrote the story in rhyme for use on a free coloring book issued by the chain in 1939. By 1946, six million copies were in print. When May hit financial trouble, the store relinquished the rights to the work back to its creator, who continued the work’s life in print form, but also increased the character’s exposure through commissioning of a song, and the aforementioned cartoon. The character would make him a millionaire.

We begin with another item out of chronological sequence, overlooked last week. Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (Jam Handy, 11/11/48 – Max Fleischer, dir.), technically qualifies as a commercial film for hire, though few today tend to classify it as such. The character was the holiday invention of an employee of Montgomery Ward department stores. Robert May, who originally wrote the story in rhyme for use on a free coloring book issued by the chain in 1939. By 1946, six million copies were in print. When May hit financial trouble, the store relinquished the rights to the work back to its creator, who continued the work’s life in print form, but also increased the character’s exposure through commissioning of a song, and the aforementioned cartoon. The character would make him a millionaire.

Montgomery Ward continued to maintain some connection to the character by the time of release of the cartoon, as original prints of the film (a preserved version of which has been made available to the internet by the Library of Congress) include a second card in the titles reading “Christmas Greetings from Montgomery Ward”. It is unknown how the distrinution of the film was handled – whether the film was offered free to theatres as an “added attraction” as with the Chevrolet films of the 1930’s, or possibly shown on the premises of some of the larger stores. The most notable difference, however, between the original release print and those that typically circulate is that the hit song of the same name, recorded by Gene Autry, hadn’t been penned yet – so the credits on both ends of the film are scored by a version of “Silent Night”. The song would not be added to the titles until a 1951 re-release, which probably made theatres, considering that Montgomery Ward’s credit had been removed. In place of it, a new card was added to credit the writer and arrangers of the song. But an interesting artifact of the original release still remains – the inclusion of the word “With” on a small bulb below the main title, intended to lead into the proclaiming of “Christmas Greetings”, but now only leading into “Color by Technicolor”.

Bringing Max Fleischer out of his forced retirement, and placing him in the director’s chair in place of brother Dave, was a surprise. Still, there is something unsettling about the appearance of the final product, making it appear that Max by this time was a little bit rusty, or unable to keep in line a group of possibly unfamiliar animators and inkers. Lacking is the smoothness in execution of a Color Classic, or the fineness in line of either of his feature projects. In fact, the film does not even come close to the technical skill previously exhibited by Jam Handy itself in the Nicky Nome series, more closely resembling that series’ primitive beginnings in “A Coach For Cinderella”. Particularly in close-ups, outlines waver and wobble from cel to cel. Inbetweening work seems rough, and motion far from smooth. There is a tendency to fall back on repeating cycles to save cost or effort – something Max was never known for in his previous films. And animation in some crowd scenes in a public arena at the end of the film is minimal to downright shoddy. While the storytelling is efficient, and the film maintains some definite character charm, there remains something lacking that keeps it from maintaining the status of a classic or near-classic, placing it substantially below the quality of competing studios of the day. To me, it closely resembles the problems of veteran Ted Eshbaugh dealing with an unfamiliar staff and an effort to bring his style up to 1940’s specs, in the unsuccessful short, “Captain Cub”. What causes brought this about may never be precisely known. Still, it makes one wish the project had been given to Max’s old veterans at Famous, who probably would have turned out a competent Noveltoon with much more fluid results.

Bringing Max Fleischer out of his forced retirement, and placing him in the director’s chair in place of brother Dave, was a surprise. Still, there is something unsettling about the appearance of the final product, making it appear that Max by this time was a little bit rusty, or unable to keep in line a group of possibly unfamiliar animators and inkers. Lacking is the smoothness in execution of a Color Classic, or the fineness in line of either of his feature projects. In fact, the film does not even come close to the technical skill previously exhibited by Jam Handy itself in the Nicky Nome series, more closely resembling that series’ primitive beginnings in “A Coach For Cinderella”. Particularly in close-ups, outlines waver and wobble from cel to cel. Inbetweening work seems rough, and motion far from smooth. There is a tendency to fall back on repeating cycles to save cost or effort – something Max was never known for in his previous films. And animation in some crowd scenes in a public arena at the end of the film is minimal to downright shoddy. While the storytelling is efficient, and the film maintains some definite character charm, there remains something lacking that keeps it from maintaining the status of a classic or near-classic, placing it substantially below the quality of competing studios of the day. To me, it closely resembles the problems of veteran Ted Eshbaugh dealing with an unfamiliar staff and an effort to bring his style up to 1940’s specs, in the unsuccessful short, “Captain Cub”. What causes brought this about may never be precisely known. Still, it makes one wish the project had been given to Max’s old veterans at Famous, who probably would have turned out a competent Noveltoon with much more fluid results.

The story is much as one would expect, though said to mirror some elements from the original poem that have not been traditionally maintained in later retellings. Rudolph is not part of the extended family of Santa’s team, but merely a deer in a community populated by such species, asleep in his bed with his stocking hung in anticipation of Santa’s annual arrival. No explanation is provided as to his power to fly, which does not exhibit itself until he is hitched to Santa’s sleigh. So do all reindeer fly naturally, or does the flight power come from the reins of the sleigh? As for Santa himself, the problem he faces is thick fog rather than overall stormy conditions, His team exits Santa’s castle via a pivoting slide-ramp built into the wall, that reminds one of some secret entrance devised for some Superman villain. Santa’s flight efforts before reaching the home of the deer have some unexpected close-encounters, including a crash into some tree limbs, a sprawl atop a pitched roof, and a near-collision with an airplane. (If the fog is that bad, how cone commercial aviation isn’t grounded?) When Santa reaches Rudolph’s room, the light from his nose is visible right through his blanket, and Santa gets the grand idea to have Rudy join his team. (Lucky he has some extra reins to allow for fitting of a ninth reindeer.) Rudolph writes a note to his parents – “Deer Mommy and Daddy”, explaining that he has gone to help Santa. I’ve often wondered at the efficiency of a bright red nose for navigating through fog. Brightness alone isn’t the ticket, as use of high-beams against fog merely causes reflection and glare against the moisture rather than an ability to see through it. Does the red color somehow equate to the qualities of an amber fog light? Oh, well, one shouldn’t overthink a Christmas story. Anyway, Rudolph gets Santa through, and is decorated by Santa in a public arena event, with a medal reading “Commander in Chief.”

The story is much as one would expect, though said to mirror some elements from the original poem that have not been traditionally maintained in later retellings. Rudolph is not part of the extended family of Santa’s team, but merely a deer in a community populated by such species, asleep in his bed with his stocking hung in anticipation of Santa’s annual arrival. No explanation is provided as to his power to fly, which does not exhibit itself until he is hitched to Santa’s sleigh. So do all reindeer fly naturally, or does the flight power come from the reins of the sleigh? As for Santa himself, the problem he faces is thick fog rather than overall stormy conditions, His team exits Santa’s castle via a pivoting slide-ramp built into the wall, that reminds one of some secret entrance devised for some Superman villain. Santa’s flight efforts before reaching the home of the deer have some unexpected close-encounters, including a crash into some tree limbs, a sprawl atop a pitched roof, and a near-collision with an airplane. (If the fog is that bad, how cone commercial aviation isn’t grounded?) When Santa reaches Rudolph’s room, the light from his nose is visible right through his blanket, and Santa gets the grand idea to have Rudy join his team. (Lucky he has some extra reins to allow for fitting of a ninth reindeer.) Rudolph writes a note to his parents – “Deer Mommy and Daddy”, explaining that he has gone to help Santa. I’ve often wondered at the efficiency of a bright red nose for navigating through fog. Brightness alone isn’t the ticket, as use of high-beams against fog merely causes reflection and glare against the moisture rather than an ability to see through it. Does the red color somehow equate to the qualities of an amber fog light? Oh, well, one shouldn’t overthink a Christmas story. Anyway, Rudolph gets Santa through, and is decorated by Santa in a public arena event, with a medal reading “Commander in Chief.”

Doggone Tired (MGM, 7/30/49 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Almost a basic Tom and Jerry setup – and one which had been somewhat explored by the cat and mouse in “Quiet, Please”, and would be re-exploited in reverse in “Sleepy Time Tom”. A hunter and his dog arrive late at night at a hunting cabin. The dog instantly zeroes in on the scent of a rabbit in his hutch, and wants to ferret him out. But the hunter insists it’s too late for hunting, and that they should get a good-night’s sleep, which they will both need in order to blast that bunny in the morning. The rabbit overhears, and sets out to do everything to ensure that the dog will have no rest. Of course, the gags are purely Avery, and run the gamut of ways to disturb slumber. A dripping faucet. A flashing light bulb. An artificial “fly” in the room, using tissue paper and a comb for sound, and a feather for facial contact (then substituting a mallet for a fly swatter). A false fire alarm (while attaching roller skates to the dog’s feet). A candlestick switched with a stick of dynamite. And a fake rainstorm, created with a garden sprinkler, a flashlight, a sheet of aluminum to rattle for thunder, and a phonograph record of “The Storm”, played by the California Sunshine Boys. When 5 o’clock hits, the hunter is raring and ready for the hunt, while the dog can’t maintain energy longer than 3 seconds before falling asleep again. He finally follows his master, carrying a pillow to rest his head on. At the entrance to the rabbit hole, the hunter pulls his pillow away, causing the dog to fall into the hole. He meets up with the rabbit, now equally tired from the night’s workout, about to settle down to sleep in his own bed. The dog snarls fiercely, and appears ready to lunge. But suddenly, there is quiet, and the hunter is left to wonder what’s going on down there. The rabbit and dog have made a peace, both in dire need of rest, and settled down to sleep in the same bed. The rabbit pantomimes to the dog for him to blow out the candle on the end table – resulting in a repeat of the explosion gag that blackened the dog’s nose from the previous substitution of a dynamite stick, for the iris out.

Doggone Tired (MGM, 7/30/49 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Almost a basic Tom and Jerry setup – and one which had been somewhat explored by the cat and mouse in “Quiet, Please”, and would be re-exploited in reverse in “Sleepy Time Tom”. A hunter and his dog arrive late at night at a hunting cabin. The dog instantly zeroes in on the scent of a rabbit in his hutch, and wants to ferret him out. But the hunter insists it’s too late for hunting, and that they should get a good-night’s sleep, which they will both need in order to blast that bunny in the morning. The rabbit overhears, and sets out to do everything to ensure that the dog will have no rest. Of course, the gags are purely Avery, and run the gamut of ways to disturb slumber. A dripping faucet. A flashing light bulb. An artificial “fly” in the room, using tissue paper and a comb for sound, and a feather for facial contact (then substituting a mallet for a fly swatter). A false fire alarm (while attaching roller skates to the dog’s feet). A candlestick switched with a stick of dynamite. And a fake rainstorm, created with a garden sprinkler, a flashlight, a sheet of aluminum to rattle for thunder, and a phonograph record of “The Storm”, played by the California Sunshine Boys. When 5 o’clock hits, the hunter is raring and ready for the hunt, while the dog can’t maintain energy longer than 3 seconds before falling asleep again. He finally follows his master, carrying a pillow to rest his head on. At the entrance to the rabbit hole, the hunter pulls his pillow away, causing the dog to fall into the hole. He meets up with the rabbit, now equally tired from the night’s workout, about to settle down to sleep in his own bed. The dog snarls fiercely, and appears ready to lunge. But suddenly, there is quiet, and the hunter is left to wonder what’s going on down there. The rabbit and dog have made a peace, both in dire need of rest, and settled down to sleep in the same bed. The rabbit pantomimes to the dog for him to blow out the candle on the end table – resulting in a repeat of the explosion gag that blackened the dog’s nose from the previous substitution of a dynamite stick, for the iris out.

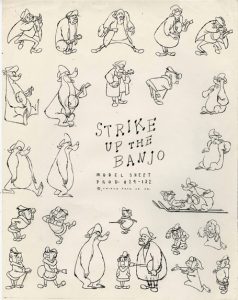

The Ragtime Bear (UPA/Columbia, 9/8/49, John Hubley, dir.) – The first appearance of Mister Magoo and Waldo. Magoo still needed a lot of clean-up in design (much of which would already be in place by his second episode, “Spellbound Hound”), and at times looks downright ugly. Waldo is closer to his typical appearance. They are on a motor jaunt in Magoo’s jalopy to the posh ski resort, Hodge Podge Lodge. Magoo’s nearsightedness is established early, as he crashes his flivver into a tree, awakening a bear sleeping in its limbs. Exiting the car, Magoo is seen standing directly in front of a sign for the lodge, yet turns to the camera, asking an unseen narrator for directions. Jim Backus, in his own normal voice, responds to Magoo, “Can’t you read the sign?” “Well, certainly I can read the sign”, grumbles Magoo – “What does it say?” We know Magoo’s weakness from the start.

The Ragtime Bear (UPA/Columbia, 9/8/49, John Hubley, dir.) – The first appearance of Mister Magoo and Waldo. Magoo still needed a lot of clean-up in design (much of which would already be in place by his second episode, “Spellbound Hound”), and at times looks downright ugly. Waldo is closer to his typical appearance. They are on a motor jaunt in Magoo’s jalopy to the posh ski resort, Hodge Podge Lodge. Magoo’s nearsightedness is established early, as he crashes his flivver into a tree, awakening a bear sleeping in its limbs. Exiting the car, Magoo is seen standing directly in front of a sign for the lodge, yet turns to the camera, asking an unseen narrator for directions. Jim Backus, in his own normal voice, responds to Magoo, “Can’t you read the sign?” “Well, certainly I can read the sign”, grumbles Magoo – “What does it say?” We know Magoo’s weakness from the start.

Inside the lodge, Magoo introduces the bear as his nephew. The nervous desk clerk extends a hand in friendship, and receives a powerful bear hug, leaving him markedly compressed. Carrying the banjo, Magoo ascends a staircase, failing to make a turn at a landing, and slamming back down. The bear regains the instrument and starts playing, to Magoo’s consternation. Magoo carries the banjo to a slope leading to the ski lift, and is about to toss it into a canyon, when he thinks better of the idea, and instead places the instrument in the seat of one of the ascending lift chairs. He chuckles to himself, thinking his troubles at an end, until the musical strains are heard again, far above him. The bear has somehow gotten to the mountaintop, and descends on skis, playing a vigorous bluegrass tune. Magoo just happens to be standing on the ski-jump ramp as the bear’s path intersects his, and collision occurs. Riding on the point of the skis, Magoo gives Waldo a final warning, seizes the banjo, and attempts to step off. He instantly breaks into an endless series of cartwheels down the slope (cleverly matched with the sound effect of banjo strings plucked in ultra-high notes below the tuning bridge), and lands with his head buried in the snow.

The final sequence takes place inside a lodge bedroom at night, while snow outside blankets the general area. (A notable continuity error is that the snowflakes are seen in all exterior long shots, but never through the windows of the bedroom.) Magoo sleeps, with the banjo under his arm, and a shotgun across his chest, to ensure that his nephew will not attempt any further shenanigans. The bear sulks in a bunk near the window, until an idea hatches. Spotting a bearskin rug on the floor, the bear substitutes the rug for himself in the bunk. Then the bear creeps up on Magoo, cautiously assuming the pose of the rug from time to time. He reaches a paw over Magoo’s chest, and pulls the trigger of the shotgun. The blast arouses Magoo, but by this time the bear has assumed his rug-pose on the floor, while the rug and bunk are riddled with buckshot holes. Magoo panics at what he has done to his nephew, then believes he can help the situation with “plenty of hot water”. He runs to the sink for it, leaving the banjo unattended. Just as the bear is about to seize the instrument, the real Waldo appears at the door, finally out of the canyon, and the bear is forced to resume his rug pose. Seeing the bunk, despite its gunshot condition, all exhausted Waldo can think of is sleep, and lies down atop the dilapidated rug. Magoo enters, dousing Waldo with a jug of hot water. “Waldo, you’re alive!” states a relieved Magoo. Apologizing, Magoo returns the banjo to Waldo, as if all is forgiven – but reverts to his old grouchy self by raising the shotgun, and reiterating “And if you play one note, I’ll blast you!” Waldo, not knowing what to make of this, withdraws his hand as far from the banjo as he can, not anxious to arouse his irate uncle’s temper. Behind him springs up the bear, who is not about to let this situation go unresolved – and reaches a paw down over Waldo to begin playing the bluegrass theme. A long shot of the cabin exterior shows us repeated gunshot blasts from within, blowing holes through the windows and log walls, with the figures of Waldo and Magoo exiting the door in silhouette and chasing up and down the hills, punctuated by more gunfire. The music and pursuit continue, as Waldo again falls into the same canyon crevass, while Magoo, unaware his target has disappeared, continues on endlessly into the night with gun blazing, while, back in his original tree, the image of the bear is seen in the limbs above, playing his bluegrass to his heart’s content against the snowfall, for the fade out.

The final sequence takes place inside a lodge bedroom at night, while snow outside blankets the general area. (A notable continuity error is that the snowflakes are seen in all exterior long shots, but never through the windows of the bedroom.) Magoo sleeps, with the banjo under his arm, and a shotgun across his chest, to ensure that his nephew will not attempt any further shenanigans. The bear sulks in a bunk near the window, until an idea hatches. Spotting a bearskin rug on the floor, the bear substitutes the rug for himself in the bunk. Then the bear creeps up on Magoo, cautiously assuming the pose of the rug from time to time. He reaches a paw over Magoo’s chest, and pulls the trigger of the shotgun. The blast arouses Magoo, but by this time the bear has assumed his rug-pose on the floor, while the rug and bunk are riddled with buckshot holes. Magoo panics at what he has done to his nephew, then believes he can help the situation with “plenty of hot water”. He runs to the sink for it, leaving the banjo unattended. Just as the bear is about to seize the instrument, the real Waldo appears at the door, finally out of the canyon, and the bear is forced to resume his rug pose. Seeing the bunk, despite its gunshot condition, all exhausted Waldo can think of is sleep, and lies down atop the dilapidated rug. Magoo enters, dousing Waldo with a jug of hot water. “Waldo, you’re alive!” states a relieved Magoo. Apologizing, Magoo returns the banjo to Waldo, as if all is forgiven – but reverts to his old grouchy self by raising the shotgun, and reiterating “And if you play one note, I’ll blast you!” Waldo, not knowing what to make of this, withdraws his hand as far from the banjo as he can, not anxious to arouse his irate uncle’s temper. Behind him springs up the bear, who is not about to let this situation go unresolved – and reaches a paw down over Waldo to begin playing the bluegrass theme. A long shot of the cabin exterior shows us repeated gunshot blasts from within, blowing holes through the windows and log walls, with the figures of Waldo and Magoo exiting the door in silhouette and chasing up and down the hills, punctuated by more gunfire. The music and pursuit continue, as Waldo again falls into the same canyon crevass, while Magoo, unaware his target has disappeared, continues on endlessly into the night with gun blazing, while, back in his original tree, the image of the bear is seen in the limbs above, playing his bluegrass to his heart’s content against the snowfall, for the fade out.

For those who haven’t seen it, my special edition, with reconstructed end title to replace the “Columbia Favorite” reissue, is included below.

The Big Drip (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 11/25/49 – I. Sparber, dir.) – At the Miracle Weather Bureau (if we guess the weather, it’s a miracle), a stork fires a marble shot inside a pinball machine marked “Weather Calculator”. The ball continually bounces off one of the bumpers, chalking up a score on the “rain” wheel of 40 days. The animals organize a Jungle Ark Project (work now or swim later). An elephant jumps on planks positioned atop the ship’s railing, bending the planks in a U to form the hull braces. A buzzsaw formation of termites is unleashed from a bottle, sawing logs into planks. A cross-eyed hippo assists Buzzy the crow by hammering nails as Buzzy holds them – well, actually, missing the nail, and flattening Buzzy instead. A giraffe serves as crane to hoist deck planks atop the ship, and sawfish cut away the overhanging edges to fit the planks into place. Pelicans serve as paintpots with their pouched bills, for painting the sides of the ship. A Christening ceremony splits the front of the ship on the impact of the bottle – but a convenient zipper zips everything up ship-shape again. Then comes the storm. One cloud installs a water tap on its side to release its load, while the old gag is revisited of a lightning bolt opening up the underside of another cloud like a can opener. A turtle bravely stands his post at the ship’s wheel, every now and then disappearing into his shell to pour out water from within with a bailing pail. The ark opens a giant umbrella over itself to help the situation. Eventually, the clouds wring out the last drop as if from a dish towel, and the sun comes out to lead us in song. An elephant and mouse pull at a rope which we assume is fastened to an anchor, but in reality is tied to a large bathtub stopper in the bed of the sea below. The stopper is pulled, and the flood waters recede, setting the ark dry and rocking atop a mountain peak. The ending, cut from all television prints, is signaled by the notes of the standard Paramount fanfare, indicating that they have landed atop the Paramount mountain. Many efforts have been made to restore this “lost” end title (including disputes over whether the film was produced in Technicolor or Polacolor), and the version embedded below is about as competent a job as any.

The Big Drip (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 11/25/49 – I. Sparber, dir.) – At the Miracle Weather Bureau (if we guess the weather, it’s a miracle), a stork fires a marble shot inside a pinball machine marked “Weather Calculator”. The ball continually bounces off one of the bumpers, chalking up a score on the “rain” wheel of 40 days. The animals organize a Jungle Ark Project (work now or swim later). An elephant jumps on planks positioned atop the ship’s railing, bending the planks in a U to form the hull braces. A buzzsaw formation of termites is unleashed from a bottle, sawing logs into planks. A cross-eyed hippo assists Buzzy the crow by hammering nails as Buzzy holds them – well, actually, missing the nail, and flattening Buzzy instead. A giraffe serves as crane to hoist deck planks atop the ship, and sawfish cut away the overhanging edges to fit the planks into place. Pelicans serve as paintpots with their pouched bills, for painting the sides of the ship. A Christening ceremony splits the front of the ship on the impact of the bottle – but a convenient zipper zips everything up ship-shape again. Then comes the storm. One cloud installs a water tap on its side to release its load, while the old gag is revisited of a lightning bolt opening up the underside of another cloud like a can opener. A turtle bravely stands his post at the ship’s wheel, every now and then disappearing into his shell to pour out water from within with a bailing pail. The ark opens a giant umbrella over itself to help the situation. Eventually, the clouds wring out the last drop as if from a dish towel, and the sun comes out to lead us in song. An elephant and mouse pull at a rope which we assume is fastened to an anchor, but in reality is tied to a large bathtub stopper in the bed of the sea below. The stopper is pulled, and the flood waters recede, setting the ark dry and rocking atop a mountain peak. The ending, cut from all television prints, is signaled by the notes of the standard Paramount fanfare, indicating that they have landed atop the Paramount mountain. Many efforts have been made to restore this “lost” end title (including disputes over whether the film was produced in Technicolor or Polacolor), and the version embedded below is about as competent a job as any.

Snow Foolin’ (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 12/16/49 – T. Sparber, dir.) – On a clear day, a rabbit turns the page of a daily wall calendar to December 21 – the first day of Winter. In a split second, he and the entire forest are covered deep in three feet of snow, as if someone emptied a load from a celestial dump truck. In a reversal of a gag from “Spring Song”, the forest animals return to a fur storage facility, exchanging their human-style duds for their natural fur coats. A fox, however, realizes there is something wrong as he exists. His fur coat barely covers half of him, has an unusual aroma about it – and is black with a white stripe. Along comes a skunk, dressed in the fox’s own red fur. The angry fox yanks the furpiece off of the skunk, tossing the unwanted black one back upon him. Putting on the fur suit, the skunk takes a whiff of his own garment, then comments to the audience in Jerry Colonna style, “Nauseating, isn’t it?” A snowball fight between rival fortresses of cats and some mice ends with a victory for the rodents, who have installed a cannon – consisting of an elephant who swallows snowballs, then takes a paddling on the rear to fire them through its trunk. Some fancy figure skating includes a stork who needs only one skate, alternating his footing between one claw and the other in one-legged stances. Also, fish who skate upside-down underneath the surface of the frozen lake, and an early version of a gag later lifted by Tex Avery for “Daredevil Droopy”, in which one skater tops another’s “figure eight” by skating into the ice a pair of fours, referring to it as “Eight, the hard way.”

Snow Foolin’ (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 12/16/49 – T. Sparber, dir.) – On a clear day, a rabbit turns the page of a daily wall calendar to December 21 – the first day of Winter. In a split second, he and the entire forest are covered deep in three feet of snow, as if someone emptied a load from a celestial dump truck. In a reversal of a gag from “Spring Song”, the forest animals return to a fur storage facility, exchanging their human-style duds for their natural fur coats. A fox, however, realizes there is something wrong as he exists. His fur coat barely covers half of him, has an unusual aroma about it – and is black with a white stripe. Along comes a skunk, dressed in the fox’s own red fur. The angry fox yanks the furpiece off of the skunk, tossing the unwanted black one back upon him. Putting on the fur suit, the skunk takes a whiff of his own garment, then comments to the audience in Jerry Colonna style, “Nauseating, isn’t it?” A snowball fight between rival fortresses of cats and some mice ends with a victory for the rodents, who have installed a cannon – consisting of an elephant who swallows snowballs, then takes a paddling on the rear to fire them through its trunk. Some fancy figure skating includes a stork who needs only one skate, alternating his footing between one claw and the other in one-legged stances. Also, fish who skate upside-down underneath the surface of the frozen lake, and an early version of a gag later lifted by Tex Avery for “Daredevil Droopy”, in which one skater tops another’s “figure eight” by skating into the ice a pair of fours, referring to it as “Eight, the hard way.”

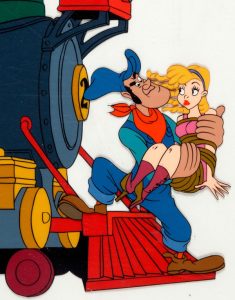

The Brave Engineer (Disney/RKO, 3/3/50 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – Speaking of Jerry Colonna, here’s the genuine article in the flesh, providing spirited narration for the saga of Casey Jones and his famous wreck immortalized in song, also harmonized in vigorous style by The King’s Men. Morning at the railroad yard finds the engines fast asleep – all except Casey’s which is slow asleep. Casey is inside the cab with it, and hastily changes into his engineer’s outfit and blows the whistle that he is ready to go. He takes on a sack of mail for Frisco as cargo. Casey is a mean man behind a throttle, and at a signal, Colonna yells, “They’re off”. How true, as the pants fly off the conductor from the engine’s speed, as does the dress of a sweet damsel standing on the platform. Casey high-balls within the yard, driving the controller in the switch tower into complete panic. He pulls and yanks switch after switch, sending Casey’s train veering at right-angle turns to avoid collision with towers and freight cars, and narrowly steering the train between two other trains just as they separate and pass each other at a junction. The switchman is barely able to pencil-in a jittery “X” on a chart to record departure on time, and collapses in a chair. “Nice day – wasn’t it?”, says Colonna, as the train passes through a dividing line between clear, sunny track and a storm front of torrential rain. Casey finds himself in the midde of a flood zone, where the rain has been coming down for five or six weeks. The entire track, and sometimes the train itself, are underwater, much like the locomotive in Van Buren’s “Wot a Night”.

The Brave Engineer (Disney/RKO, 3/3/50 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – Speaking of Jerry Colonna, here’s the genuine article in the flesh, providing spirited narration for the saga of Casey Jones and his famous wreck immortalized in song, also harmonized in vigorous style by The King’s Men. Morning at the railroad yard finds the engines fast asleep – all except Casey’s which is slow asleep. Casey is inside the cab with it, and hastily changes into his engineer’s outfit and blows the whistle that he is ready to go. He takes on a sack of mail for Frisco as cargo. Casey is a mean man behind a throttle, and at a signal, Colonna yells, “They’re off”. How true, as the pants fly off the conductor from the engine’s speed, as does the dress of a sweet damsel standing on the platform. Casey high-balls within the yard, driving the controller in the switch tower into complete panic. He pulls and yanks switch after switch, sending Casey’s train veering at right-angle turns to avoid collision with towers and freight cars, and narrowly steering the train between two other trains just as they separate and pass each other at a junction. The switchman is barely able to pencil-in a jittery “X” on a chart to record departure on time, and collapses in a chair. “Nice day – wasn’t it?”, says Colonna, as the train passes through a dividing line between clear, sunny track and a storm front of torrential rain. Casey finds himself in the midde of a flood zone, where the rain has been coming down for five or six weeks. The entire track, and sometimes the train itself, are underwater, much like the locomotive in Van Buren’s “Wot a Night”.

Casey has to stand on the engine’s roof, using his coal shovel like a paddle. The slog through the water and mud makes Casey eight hours behind schedule. As his train emerges into daylight again, spouting water out of the smokestack to lighten the load, Casey resolves to “Keep knockin’ at the fire door – Don’t give up yet” in a desperate effort to make schedule. But the path ahead contains a veritable gauntlet of obstacles and interferences. First a cow on the tracks – then a girl tied to the tracks (whom Casey scoops up in his arms while standing on the cowcatcher, then deposits with the station master at the next station on the fly as “she-mail”). An anarchist blows up a trestle ahead with dynamite – but Casey’s engine manages to crawl its way back up the canyon wall onto the track again (with Colonna commenting at the train’s exertion, “Not in condition – smokes too much”). A gang of railroad bandits can’t stop Casey, who vanquishes them with blows from his coal shovel. The obstacles seemingly past. Casey pulls on the throttle to give the engine full steam – and breaks the handle entirely off. Treating the incident like nothing, he casually tosses the handle off the side of the train, and resumes shoveling coal into the boiler as fast as he can. In vivid animation worthy of a Disney feature, the train begins to go berserk.

Casey has to stand on the engine’s roof, using his coal shovel like a paddle. The slog through the water and mud makes Casey eight hours behind schedule. As his train emerges into daylight again, spouting water out of the smokestack to lighten the load, Casey resolves to “Keep knockin’ at the fire door – Don’t give up yet” in a desperate effort to make schedule. But the path ahead contains a veritable gauntlet of obstacles and interferences. First a cow on the tracks – then a girl tied to the tracks (whom Casey scoops up in his arms while standing on the cowcatcher, then deposits with the station master at the next station on the fly as “she-mail”). An anarchist blows up a trestle ahead with dynamite – but Casey’s engine manages to crawl its way back up the canyon wall onto the track again (with Colonna commenting at the train’s exertion, “Not in condition – smokes too much”). A gang of railroad bandits can’t stop Casey, who vanquishes them with blows from his coal shovel. The obstacles seemingly past. Casey pulls on the throttle to give the engine full steam – and breaks the handle entirely off. Treating the incident like nothing, he casually tosses the handle off the side of the train, and resumes shoveling coal into the boiler as fast as he can. In vivid animation worthy of a Disney feature, the train begins to go berserk.

Its smokestack exhaust burns a hole right through the roof of a mountain tunnel as the engine passes through. Its rear cars flip around in the air, unable to maintain their footing on the tracks. The heat and friction from the engine melts tracks and switches along the way. Running out of coal, Casey busts up his coal shovel as additional kindling, and tosses it into the boiler. Gauges on the boiler pop off their mainsprings like so many jack-in-the boxes. The engine itself begins to come apart piece by piece. The smokestack pops off, with Casey re-implanting it upside-sown. The cowcatcher flies off, with Casey dragging it back. The metal support straps for the mounting of the boiler pop off like a fat-man’s over-extended belt, with the boiler frame expanding like a giant red-hot balloon. Casey hammers and pounds everywhere on the engine to keep machinery and fire together. But below, slowly chugging uphill on the same track, is a double-locomotive freight train, hauling a long line of loaded cars. The collision is imminent between an irresistible force and a seemingly immovable object. Casey’s conductor hollers “Here comes a freight”. Unable to hear him properly over the steam of the engine, Casey misinterprets the inquiry, and responds, “We won’t be late.” The conductor finally gets Casey to hear the word “Freight”. “So what?”, inquires Casey disdainfully. “So long” says the conductor, as he jumps ship over the side. The crew of the freight train hastily abandons the other machine, and Casey plows headlong into the freight for the inevitable crash.

Its smokestack exhaust burns a hole right through the roof of a mountain tunnel as the engine passes through. Its rear cars flip around in the air, unable to maintain their footing on the tracks. The heat and friction from the engine melts tracks and switches along the way. Running out of coal, Casey busts up his coal shovel as additional kindling, and tosses it into the boiler. Gauges on the boiler pop off their mainsprings like so many jack-in-the boxes. The engine itself begins to come apart piece by piece. The smokestack pops off, with Casey re-implanting it upside-sown. The cowcatcher flies off, with Casey dragging it back. The metal support straps for the mounting of the boiler pop off like a fat-man’s over-extended belt, with the boiler frame expanding like a giant red-hot balloon. Casey hammers and pounds everywhere on the engine to keep machinery and fire together. But below, slowly chugging uphill on the same track, is a double-locomotive freight train, hauling a long line of loaded cars. The collision is imminent between an irresistible force and a seemingly immovable object. Casey’s conductor hollers “Here comes a freight”. Unable to hear him properly over the steam of the engine, Casey misinterprets the inquiry, and responds, “We won’t be late.” The conductor finally gets Casey to hear the word “Freight”. “So what?”, inquires Casey disdainfully. “So long” says the conductor, as he jumps ship over the side. The crew of the freight train hastily abandons the other machine, and Casey plows headlong into the freight for the inevitable crash.

At Frisco bay, a lonely station master paces back and forth, speculating on the fate of the overdue mail shipment. Ultimately giving up hope, he treads over to a chalk board and begins to erase Casey’s name from the arrival column. But a whistle is heard from up the hill. Miraculously, Casey rolls down the track, with only the front cab wall, the train whistle, and four cracking wheels left of his engine – yet proudly carrying the mail sack. He also holds up his gold pocket watch to the camera, where a mechanism of turning wheels inside displays the words “On Time”, followed by the additional word, “Almost”.

Helter Swelter (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 8/25/50 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – It feels like this one was produced as a companion film to “Snow Foolin’”, beginning again with the calendar, now reading June 21 – the longest day of the year, as depicted by a calendar sheet whose digits extend all the way to the floor. Only a few gags focus on the subject of a summer heat wave. A hen in her chicken coop fans herself and perspires profusely over her nest, then checks on the status of her egg. A cutaway view shows us the chick inside, relaxing comfortably, thanks to an electric fan he has installed within. A turtle is making slower going than usual under the sun’s rays, and retracts his head inside his shell, to look at the controls of an interior automobile-style dashboard. Flicking a switch, he transforms his shell into a foldable convertible top, allowing him to pick up the pace in the cooling air. Even the sun itself carries an ice block on its head to beat the heat, and joins the throngs of New Yorkers at Coney Island beach, guzzling soda pop and eating hot dogs, for the sing-along.

Helter Swelter (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 8/25/50 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – It feels like this one was produced as a companion film to “Snow Foolin’”, beginning again with the calendar, now reading June 21 – the longest day of the year, as depicted by a calendar sheet whose digits extend all the way to the floor. Only a few gags focus on the subject of a summer heat wave. A hen in her chicken coop fans herself and perspires profusely over her nest, then checks on the status of her egg. A cutaway view shows us the chick inside, relaxing comfortably, thanks to an electric fan he has installed within. A turtle is making slower going than usual under the sun’s rays, and retracts his head inside his shell, to look at the controls of an interior automobile-style dashboard. Flicking a switch, he transforms his shell into a foldable convertible top, allowing him to pick up the pace in the cooling air. Even the sun itself carries an ice block on its head to beat the heat, and joins the throngs of New Yorkers at Coney Island beach, guzzling soda pop and eating hot dogs, for the sing-along.

More fun without sun, in ‘51, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Your criticisms of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” are right on the money. I grew up with the Robert L. May storybook, and I loved the illustrations and the verse. When, sometime in the ’90s, I found out that Max Fleischer had made a cartoon out of it, naturally I had high expectations. Years passed before I was finally able to see it, which made the experience all the more disappointing for all the reasons you describe. I don’t know whom to blame either, but there’s no question that the cartoon lacks a certain “Christmas magic” — which cannot be said for he book that inspired it.

“It Ain’t Gonna Rain No Mo'” was a common singalong song at Boy Scout jamborees, especially when it rained, which it usually did. In the version I learned, the chorus ended with the line “How in the heck can I wash my neck if it ain’t gonna rain no mo’?” Because of that heck/neck internal rhyme, I long assumed that the line “How in the world can the old folks tell,” as heard in “The Big Drip”, must have originally been “How in the Hell can the old folks tell….” However, in his original 1923 recording of the song Wendell Hall sang “world” in the chorus every single time. If there ever was any censorship of that song, it must have happened right at the get-go.

Both “It Ain’t Gonna Rain No Mo'” and “Polly Wolly Doodle” contain a verse about a grasshopper sitting on a railroad track. I gather that periodic locust swarm could make the tracks dangerously slippery.

And speaking of sitting on railroad tracks: Some years ago, after having seen countless scenes like the one in “The Brave Engineer” of a villain tying the heroine to the railroad tracks, I started to wonder whether that ever really happened. So I looked into it and discovered that the scenario originated in theatrical melodrama in 1865. It became so widely imitated, so quickly, that it’s impossible now to determine exactly who came up with it in the first place. By the mid-19th century, many people were feeling threatened by the increasing mechanisation of society, so this was the perfect metaphor for the Zeitgeist. If such an incident ever actually occurred, it would have been a case of life imitating art.

Re: Rudolph- all the reindeer walking around on their hind legs really bothered me.

And speaking of melodrama….

“A Cold Romance” (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 10/6/49 — Mannie Davis, dir.) opens in media res with Mighty Mouse battling Oil Can Harry in an Arctic trading post. Outside, the narrator tells us, “it’s raining cats and dogs” — and lo and behold, cats and dogs start falling from the sky, exactly as they did when this gag was used in the original Oil Can Harry melodrama “The Banker’s Daughter” (1933) with Fanny Zilch and J. Leffingwell Strongheart. The narrator then drives home his point by telling us that the rain is coming down in buckets — and so it is, literally, in actual buckets! Ha! Then a fork of lightning pins Mighty Mouse to a tree, and Harry twists the ends of it as though they were wires, leaving the villain free to pursue the heroine Little Nell. Mighty Mouse eventually frees himself by melting the lightning away with energy beams from his eyes, and off he goes to — well, you know.

The heroine doesn’t get tied to the railroad tracks in this cartoon, but she does get trapped on a conveyor belt in an ore refinery, which serves basically the same dramatic purpose.

A bit off topic: The list of shorts for Looney Tunes Collectors Choice volume 2 are available on Dohtem.com, and the Warner Archive Facebook page.

“Anti-Cats” (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 3/50 — Mannie Davis, dir.) begins as two mice carry a third on a stretcher through a raging blizzard. They try to find warmth and shelter inside a house, but the resident cat throws them back out into the snowstorm. Mighty Mouse arrives incognito, disguised in a trench coat and hat, and helps the mice turn the tables on the cat.

The “Rudolph” cartoon benefits from the tendency to get sentimental over cheap or downright tacky stuff at Christmastime. As many other yuletide stories remind us, it’s the thought behind the product, rather than the product itself, that counts. As a piece of animation of its time, “Rudolph” falls short almost even by Terrytoons standards (no wonder that plane almost hits Santa’s sleigh: it has no windows), but it’s like a kitschy Christmas ornament that’s been in the family for years that you can’t quite bring yourself to part with. One of the backgrounds looks like it was left over from “Gulliver’s Travels.” The scene of Santa sitting on Rudolph’s bed, his arms around Rudolph as he says “I need you tonight,” is a little disturbing out of context. According to Fleischerologist Leslie Cabarga, the cartoon was a television perennial until the 1964 Rankin-Bass version took over.

More than one animation book says Max Fleischer was little more than a figurehead at Jam Handy. Charles Solomon’s “Enchanted Drawings” claims that Magoo is a secondary character in “Ragtime Bear,” but that’s obviously not true. It’s a great coffee table book (especially the original version whose dust jacket is made of cel material) and arguably the most satisfying comprehensive history of animation, but from the text you can’t help wondering how many of the cartoons Solomon actually saw.

The Rudolph short was responsible for one of the funniest RiffTrax jokes ever:

“I need you tonight.”

“WHOA!”

The live audience laughed so hard the riffers missed telling THREE jokes.