By the early 1960’s, the old studio system that had nourished Hollywood animation departments was but a memory. Major studios such as Paramount found that they could satisfy the market for cartoons by getting them from just about anybody. Paramount itself supplemented its own cartoons with the product of newcomers sucSh as Al Brodax of King Features Syndicate, William Snyder and Gene Deitch of Rembrandt Films, Hal Seeger, and John Hubley. It must have rankled some of the old timers to see some of these newcomers take their seats at Oscar dinners, and wind up with certificates and gold statuettes while the old regime received no notice whatsoever. Paramount’s releases were all over the map – literally, as we shall see.

Home Sweet Swampy (May, 1962, Comic Kings – Beetle Bailey – executive producer, Al Brodax, Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Paramount’s relation with Brodax, beginning with the King Features Popeye Cartoons, was still pretty good in 1962, when King Features turned their attention to various comic strips under their ownership for adaptation to the screen. Although Paramount failed to attract attention with its pilot episode for the Krazy Kat series (the contract for such episodes instead split between Gene Deitch at Rembrandt Films and Format Films), Paramount landed an exclusive on the production of 49 episodes of Snuffy Smith and Barney Google, and also produced over half of the episodes of Beetle Bailey. To showcase their work, and allow for some public exposure of the series beyond the small screen, several of the Paramount episodes were licensed for inclusion in Paramount’s theatrical release schedule, under the banner “Comic Kings”.

Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey had become the most popular of service comedy comics around, and had front page coverage on the Sunday comics supplement, “Comics Weekly” (no association with the British humour magazine “Puck”) of Hearst Newspapers. It was the first chosen for debut on the big screen. Beetle Bailey and Sergeant Snorkel have both been awarded ten-day furloughs. For Bailey, this is good news. For Snorkel, not so much. The Colonel orders Snorkel to take the furlough. Snorkel doesn’t want to do it, claiming that even going into town to get some spark plugs gets him homesick for Camp Swampy. Snorkel arranges with the platoon hipster Cosmo to keep him apprised of the doings at the camp by way of walkie talkie, as he is marched off the post. No sooner out the gate and in town, Snorkel is already using his contact to find out who’s in the guardhouse, who’s on K.P., etc. On the streets of town they encounter a troop of boy scouts, including a bugler. Sgt. Snorkel makes a request for Mess Call, but the youthful bugler considers the number too square. At a French eatery, Bailey is trying to be sophisticated with the menu, but Snorkel asks for army chow, referring to it as “S.O.S.” (military slang for chipped beef on toast). While Bailey tells the restaurant staff they have to humor the Sarge, they are perplexed as to what “S.O.S.” means. (I’d tell you, but I don’t like to use that kind of language.) Bailey and Snorkel are both bounced from the restaurant. They wind up in the middle of the night back at the gates of Camp Swampy, trying to break in. Sarge leaves a Snorkel-sized hole in the fence. The Colonel catches them, and Snorkel refuses to take the rest of his furlough – so winds up in the guard house for disobeying a direct order. Bailey unwittingly shares Snorkel’s fate, and is saddled with the task of peeling mountains of potatoes. Still, the two spend the time singing the strains of “There’s No Place Like Home”. Song: an original theme song is composed for Beetle Bailey, used throughout the 50 episodes released.

Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey had become the most popular of service comedy comics around, and had front page coverage on the Sunday comics supplement, “Comics Weekly” (no association with the British humour magazine “Puck”) of Hearst Newspapers. It was the first chosen for debut on the big screen. Beetle Bailey and Sergeant Snorkel have both been awarded ten-day furloughs. For Bailey, this is good news. For Snorkel, not so much. The Colonel orders Snorkel to take the furlough. Snorkel doesn’t want to do it, claiming that even going into town to get some spark plugs gets him homesick for Camp Swampy. Snorkel arranges with the platoon hipster Cosmo to keep him apprised of the doings at the camp by way of walkie talkie, as he is marched off the post. No sooner out the gate and in town, Snorkel is already using his contact to find out who’s in the guardhouse, who’s on K.P., etc. On the streets of town they encounter a troop of boy scouts, including a bugler. Sgt. Snorkel makes a request for Mess Call, but the youthful bugler considers the number too square. At a French eatery, Bailey is trying to be sophisticated with the menu, but Snorkel asks for army chow, referring to it as “S.O.S.” (military slang for chipped beef on toast). While Bailey tells the restaurant staff they have to humor the Sarge, they are perplexed as to what “S.O.S.” means. (I’d tell you, but I don’t like to use that kind of language.) Bailey and Snorkel are both bounced from the restaurant. They wind up in the middle of the night back at the gates of Camp Swampy, trying to break in. Sarge leaves a Snorkel-sized hole in the fence. The Colonel catches them, and Snorkel refuses to take the rest of his furlough – so winds up in the guard house for disobeying a direct order. Bailey unwittingly shares Snorkel’s fate, and is saddled with the task of peeling mountains of potatoes. Still, the two spend the time singing the strains of “There’s No Place Like Home”. Song: an original theme song is composed for Beetle Bailey, used throughout the 50 episodes released.

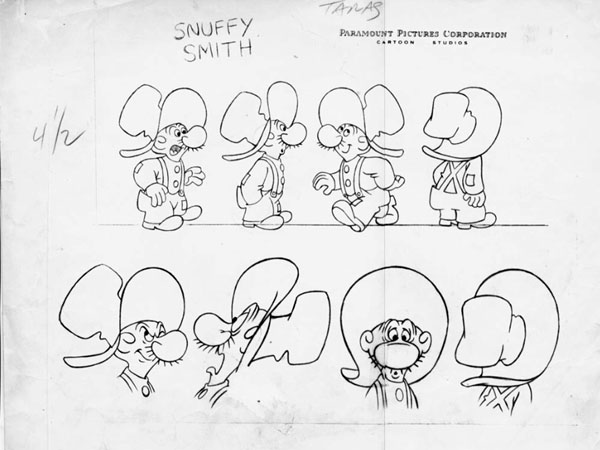

Snuffy’s Song (June, 1962 – Comic Kings (Snuffy Smith and Barney Google) – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Barney Google is visiting at the Smiths’ cabin in the hills. A paper boy delivers the paper with a toss that conks Barney in the head, A headline story relates a “Local Boy Makes Good” success tale of a million-dollar recording contract awarded to a former hog caller. Loweezy recalls that he still is a hog caller – “But they gave him a gee-tar to go with it, and it come out right purty.” Barney begins to develop dollar signs in his eyes, looking for a similar get-rich-quick opportunity. He hears Snuffy singing out in the field, doing his “chores” of chopping wood via a steam powered wood chopper propelled by a fire under an oil drum, while Snuffy himself loafs under a tree. Barney thinks the song and the chopper’s accompaniment are the “new sound”, and envisions Snuffy transformed into a pile of cash. Though Barney talks to Snuffy of millions, Snuffy asks “Is that more than $1.30?” – a sum he wants to buy a new plow, as it tuckers him out to watch Loweezy pull the old one. Barney promises him his $1.30, intending to keep what’s left over for himself.

The family embarks on a trip to Hollywood – hitching on the back end of a public bus. Snuffy asks why they don’t sit inside with the others, and Barney points out the advantages of their “air conditioned” position. They arrive at the “Seymour Stereo” building – a structure that revolves at 33 1/3 rpm like a record player – the only long-play building around, complete with giant record and tone arm on the roof (clearly inspired by the Capitol Tower on Vine Street). Barney, Snuffy, and Loweezy take the wood chopper up to Seymour’s top floor office, amidst his coterie of yes men. Once everything is set up, and Loweezy destroys a Chippendale chair to serve as kindling to fire up the contraption, everybody hears Snuffy sing, and concludes that he is a backwoods Crosby, a cornpone Caruso. Contracts are signed, while the smoke from the oil drum fills the room to blackness. A recording date is set up, with one modification – a gas burner installed under the oil drum to provide the heat. The recording begins, but the machine becomes overheated to overdrive, and skyrockets through the roof into the heavens. Barney’s eyes transform from dollar signs to “No Sale”. Seymour presses a button marked “Instant Revenge”, and three large machines act as bouncers to boot the family out of the tower. A passing newsboy shouts word of an “Extra” about the first oil drum shot into space, with the pentagon puzzled. As the drum passes in orbit in the sky, Barney comments “There goes the sweetest music this side of heaven” (quote of band slogan of Guy Lombardo). Loweezy chimes in with the slogan of the Louis Prima band: “Play pretty for the people.” Song: “Snuffy’s Song”, an original theme song which would be used throughout the series, heard here for the only time in complete form.

The following year, one additional piece of theme music was written for a Paramount television production, which never reached the big screen. In 1963, the “New Casper Cartoon Show” premiered on ABC. A new theme (below) was commissioned from the studio, which provided the animation for the new Casper installments. There were still within its scoring musical stings continuing to quote from the original Casper theme. Winston Sharples, independently of Paramount’s work, would also write or provide performances for the work of related studios of Joe Oriolo and Hal Seeger, including themes for Felix the Cat, Out of the Inkwell, The Mighty Hercules, Milton the Monster, Flukey Luke, and Stuffy Durma.

Poor Little Witch Girl (Modern Madcap introducing “Halfwitch”) (4/1/65) – The pilot episode of what would become the “Honey Halfwitch” series, though a theme song had not yet been composed. Never taking a screen credit for the series, the voice of Halfwitch for all except the last few episodes restyled by Shamus Culhane was provided by ventriloquist par excellence Shari Lewis, who also doubles as the voice of Cousin Maggie (both original voicings, to my knowledge never used in Shari’s puppet performances). Halfwitch lives with her older cousin Maggie, who is going out for a check-up upon her “evil eye” via her broomstick. Maggie tells Halfwitch she can’t ride on a broom until she grows up – which for a witch takes 500 years. Halfwitch is convinced by Fraidy Bat (a Bela Lugosi impersonator who lives upside down in one of the rafters of the cottage) to try a drop of a growth potion Maggie has on an upper shelf. Halfwitch accidentally breaks the bottle, spilling the potion all over her. She suddenly grows through the roof, standing 30 feet tall. Halfwitch is enthralled with her new perspective on life, and sings an original song, “Looka Me, Looka Me”, gracefully trapsing along as best a giantess can, showing off her new maturity. She crosses paths with Maggie, who is angry at her meddling with her potions, but restores her to her normal size. When she finds out that Halfwitch did it only to become old enough for a broom ride, Maggie relents to keep her from mischief, and Halfwitch gets her ride. Maggie complains, however, that next thing you know, Halfwirtch will want to be casting spells. Prophetic words, as Halfwitch accidentally emits sparks from her fingers in waving goodbye to Fraidy Bat, which causes a rabbit to magically appear out of his top hat. Halfwitch whispers a “Shhh” to the audience as the film c;loses, ensuring that we will not let Maggie know.

Poor Little Witch Girl (Modern Madcap introducing “Halfwitch”) (4/1/65) – The pilot episode of what would become the “Honey Halfwitch” series, though a theme song had not yet been composed. Never taking a screen credit for the series, the voice of Halfwitch for all except the last few episodes restyled by Shamus Culhane was provided by ventriloquist par excellence Shari Lewis, who also doubles as the voice of Cousin Maggie (both original voicings, to my knowledge never used in Shari’s puppet performances). Halfwitch lives with her older cousin Maggie, who is going out for a check-up upon her “evil eye” via her broomstick. Maggie tells Halfwitch she can’t ride on a broom until she grows up – which for a witch takes 500 years. Halfwitch is convinced by Fraidy Bat (a Bela Lugosi impersonator who lives upside down in one of the rafters of the cottage) to try a drop of a growth potion Maggie has on an upper shelf. Halfwitch accidentally breaks the bottle, spilling the potion all over her. She suddenly grows through the roof, standing 30 feet tall. Halfwitch is enthralled with her new perspective on life, and sings an original song, “Looka Me, Looka Me”, gracefully trapsing along as best a giantess can, showing off her new maturity. She crosses paths with Maggie, who is angry at her meddling with her potions, but restores her to her normal size. When she finds out that Halfwitch did it only to become old enough for a broom ride, Maggie relents to keep her from mischief, and Halfwitch gets her ride. Maggie complains, however, that next thing you know, Halfwirtch will want to be casting spells. Prophetic words, as Halfwitch accidentally emits sparks from her fingers in waving goodbye to Fraidy Bat, which causes a rabbit to magically appear out of his top hat. Halfwitch whispers a “Shhh” to the audience as the film c;loses, ensuring that we will not let Maggie know.

Shoeflies (10/65) – Honey Halfwitch is polishing her shoes – the non-magical way. She is met by Teeny Meany, another junior witch, who wants her to come out and play. Teeny suggests that Honey should borrow her cousin’s magic wand to speed up the polishing job. Honey does so, and the shoes go wild, treading everywhere with a mind of their own. They intentionally track mud into the house, even up the wall and along the ceiling to Fraidy Bat’s rafter. Fraidy offers advice on how to find the counterspell, while Meany runs off to Cousin Maggie to do a little tattling. Honey and Fraidy successfully put the shoes into reverse (a plot device dating back to Betty Boop’s “Baby Be Good”) and undo all the damage, setting things in order before Maggie arrives. Finding no evidence of wrongdoing, the blame is placed on Meany for telling fibs. Two songs are introduced in this episode – an original for Honey, “I’m Polishing My Shoes”, and the newly-penned “Honey Halfwitch” theme, expanding her name from simply “Halfwitch” in the previous episode.

Drive On, Nudnik (Rembrandt Films, 11/65 – Gene Deitch, dir.) – An import from Rembrandt Films of Prague. We find Nudnik, a pantomime born loser, sleeping in a pothole, which is deep enough that he can be covered and uncovered by the tank treads of construction equipment without fear of getting smushed. He finally winds up trying to drive a modern car, but nothing works right. Nudnik winds up riding in the back end of a police car, heading for a nice safe jail. It seems likely Paramount picked up this series as their attempt to compete with UA’s Pink Panther cartoon pantomimes. This was also the period when the Zagreb Studios was at its height, so Paramount may have felt they were getting some art house cachet. Song: “Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams”, a number which became to the underscore of Nudnik catoons what the Pink Panther Theme was to the Panther – spanning the length of each cartoon. The musicians seem to be familiar with traditional jazz, but intentionally play the theme comedically corny. The tune was introduced in 1931 by Bing Crosby, recorded on Victor. He would re-record it in 1939 for Decca, with an alternate take (below) circulating for decades among Crosby collectors with Bing breaking into musical swearing (”They cut out eight bars, the dirty ba——–“). Other recordings included Milfred Bailey on Brunswick, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers on Victor (their last recording), a Ben Selvin studio group on Harmony, Velvet Tone, and Clarion, another Ben Selvin group on Columbia billed under the name Ted Raph (a trombonist), and Louis Armstrong on Okeh. It became a standard, and was recorded by Eddy Howard on Columbia in 1941, Dean Martin as an album cut on Capitol, Frank Sinatra on Capitol, jazz man Stan Getz on Verve, and others who liked to delve into the Great American Songbook.

Drive On, Nudnik (Rembrandt Films, 11/65 – Gene Deitch, dir.) – An import from Rembrandt Films of Prague. We find Nudnik, a pantomime born loser, sleeping in a pothole, which is deep enough that he can be covered and uncovered by the tank treads of construction equipment without fear of getting smushed. He finally winds up trying to drive a modern car, but nothing works right. Nudnik winds up riding in the back end of a police car, heading for a nice safe jail. It seems likely Paramount picked up this series as their attempt to compete with UA’s Pink Panther cartoon pantomimes. This was also the period when the Zagreb Studios was at its height, so Paramount may have felt they were getting some art house cachet. Song: “Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams”, a number which became to the underscore of Nudnik catoons what the Pink Panther Theme was to the Panther – spanning the length of each cartoon. The musicians seem to be familiar with traditional jazz, but intentionally play the theme comedically corny. The tune was introduced in 1931 by Bing Crosby, recorded on Victor. He would re-record it in 1939 for Decca, with an alternate take (below) circulating for decades among Crosby collectors with Bing breaking into musical swearing (”They cut out eight bars, the dirty ba——–“). Other recordings included Milfred Bailey on Brunswick, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers on Victor (their last recording), a Ben Selvin studio group on Harmony, Velvet Tone, and Clarion, another Ben Selvin group on Columbia billed under the name Ted Raph (a trombonist), and Louis Armstrong on Okeh. It became a standard, and was recorded by Eddy Howard on Columbia in 1941, Dean Martin as an album cut on Capitol, Frank Sinatra on Capitol, jazz man Stan Getz on Verve, and others who liked to delve into the Great American Songbook.

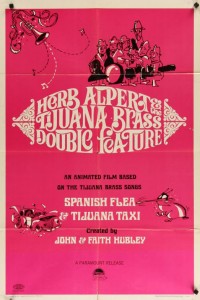

Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass Double Feature (John and Faith Hubley, April, 1966 – John Hubley, dir.) – This surprise Oscar winner was actually more of a triple feature, as the opening and closing credits give us footage of a trumpet-nosed bull charging through the credits and playing an additional early Brass hit, “The Mexican Shuffle” (many will remember this tune for its commercial use on ads for Clark Teaberry Gum). With some notable animation help from the likes of Emery Hawkins and Rod Scribner, this traditionally Hubley-stylized outing is an early-day music video, jamming into its meager 5:12 running time two additional Brass singles hits in complete form: “Spanish Flea” and “Tijuana Taxi”. (I can’t help but suspect that the title “Spanish Flea” was a wordplay on the notorious “Spanish Fly” – a sort of a “Mickey” used for nefarious purposes.) Presented entirely in pantomime, the first half focuses on the misadventures of the flea, as he puts the bite on a country mule and chicken on a vacant lot, until his two targets are chased off by a bulldozer. In a twinkling, the lot is developed into a resort hotel, by a little hotel mogul and his shapely consort. The mogul takes his frail into a cabana to fool around, while the paying guests dance and live it up. The flea only sees a new menu of targets, and gets busy chewing on the mogul, the girl, and the guests alike. The angry mogul barks orders to his crew, and suddenly the construction equipment pushes the whole resort, lock, stock, and barrel, to the next lot. The mule and chicken return, and the flea has his usual dinner upon them, before settling down for a well-earned rest in a flower.

Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass Double Feature (John and Faith Hubley, April, 1966 – John Hubley, dir.) – This surprise Oscar winner was actually more of a triple feature, as the opening and closing credits give us footage of a trumpet-nosed bull charging through the credits and playing an additional early Brass hit, “The Mexican Shuffle” (many will remember this tune for its commercial use on ads for Clark Teaberry Gum). With some notable animation help from the likes of Emery Hawkins and Rod Scribner, this traditionally Hubley-stylized outing is an early-day music video, jamming into its meager 5:12 running time two additional Brass singles hits in complete form: “Spanish Flea” and “Tijuana Taxi”. (I can’t help but suspect that the title “Spanish Flea” was a wordplay on the notorious “Spanish Fly” – a sort of a “Mickey” used for nefarious purposes.) Presented entirely in pantomime, the first half focuses on the misadventures of the flea, as he puts the bite on a country mule and chicken on a vacant lot, until his two targets are chased off by a bulldozer. In a twinkling, the lot is developed into a resort hotel, by a little hotel mogul and his shapely consort. The mogul takes his frail into a cabana to fool around, while the paying guests dance and live it up. The flea only sees a new menu of targets, and gets busy chewing on the mogul, the girl, and the guests alike. The angry mogul barks orders to his crew, and suddenly the construction equipment pushes the whole resort, lock, stock, and barrel, to the next lot. The mule and chicken return, and the flea has his usual dinner upon them, before settling down for a well-earned rest in a flower.

Part two follows the Mexican driver of the Tijuana Taxi, as a visiting band of musicians hurriedly charters the cab to get them to a mountaintop airfield in time to catch a departing flight. The ride is bouncy and fraught with hazards, as the driver careens through narrow roads, twice running over an old man on crutches (a gag Hawkins and Scribner may have remembered from Porky Pig’s “Dog Collared”), through buildings and churches, and even into the middle of the bull ring when the driver follows the wrong route at a fork in the road. The plane’s engines are revving up, but the driver gets stopped at the airport gate by a customs agent, who takes forever to examine everybody’s passport. While the taxi’s passengers shout in frustration, the cab is delayed by the agent long enough that the plane takes off without them. No matter, as the cab driver puts the engine into high-speed idle, causing enough vibration to start the car doors flapping, then ushers all the passengers back in, and takes off from the runway to provide the needed air service to get his passengers to their destination.

All three songs were of course issued by Alpert on A&M Records, which receives screen credit. “Mexican Shuffle”, along with many sound-alike versions on various labels, had a bit of action for Polydor in a cover version by Bert Kaempfert, released here in the states on Decca. Spanish Flea received two cover singles with newly-added vocals – both with different lyrics from each other. In the U.S., it appeared by Frankie Randall on RCA Victor. In England, Decca gave it to Kathy Kirby (her version sets the action in a flea circus, and writes only one verse of lyric). Vocal renditions of all three songs would appear by the Modernaires (calling themselves “The Mods” on a salute album to the TJB on Columbia. Vocal on “Tijuana Taxi” was also recorded on London records by The Cyril Stapleton Singers. Another interesting approach to the songs was performed in big band style by the New Glenn Miller Orchestra on the Columbia album, “Something New”.

“The Plumber”

The Opera Caper (Go Go Toon, 11/67 – Shamus Culhane/Ralph Bakshi, dir.) – A slapstick outing about an attempted kidnapping at the Paris Opera House. A large and a short hoodlum plan to abduct the prima donna star of the performance – but first must gain entry to the theater. A sizeable amount of time is spent attempting to use a teeter-totter to catapult them to the roof. The large one jumps on one end of the board, propelling the other to the roof, carrying a heavy metal weight. Then, the little one drops the weight, with intent for it to land on the board to propel the large hood up. It does, but the little crook fails to catch the big one, who falls back on the teeter-totter, flipping the heavy weight onto his own head. They try again, with the large hood placing the teeter-totter closer to the building – and the whole building closer to the teeter-totter. He only succeeds in smacking his head on an overhanging balcony, then getting clobbered by the counterweight again. Finally, he has the little crook jump back down from the roof together with the counterweight. Their combined weight launches the large crook clear across town and into the river. They finally settle for purchasing tickets, then skulk around the building until they pass through a door – and find themselves outside the stage entrance, with the door closing and locking behind them. Another purchase of tickets. Passing through another dark doorway, the two accidentally find themselves in the spotlight on stage, and improvise a soft-shoe to beat a hasty exit. When they finally track down the singer after her performance, followed by her manager, they enter the dressing room with a large sack, but accidentally kidnap the manager instead. C’est la guerre! Four passages from various operas are included in the soundtrack, two of which I do not recognize, and leave for identification by Paul Groh or any other volunteer. The recognizable ones are the Grand March from Verdi’s “Aida” (heard over the opening credits), and “Caro Nome”, also by Verdi, from “Rigoletto”. Aside from complete versions of each opera, the Aida March was recorded electrically by Creatore’s Band on Victor, then later by Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops, on Victor red seal. The Milan Symphony Orchestra issued a European version on Columbia, and The Columbia Light Symphony Orchestra directed by Howard Barlow issued a version on British Columbia. Caro Nome made the rounds of coloraturas, including A. Michailova on early Victor black seal, Madame Tetrazzini on Gramophone Monarch, Florence Macbeth on Columbia Exclusive Artist, Amelita Galli-Curci on red seal Victor, Marion Talley on red seal Victrola, Maria Gentile on British Columbia, Thea Phillips on British Broadcast Twelve, Lina Pagliughi on Parlophone, and Lily Pons on both Victor red seal and V-Disc, to name a few.

The Opera Caper (Go Go Toon, 11/67 – Shamus Culhane/Ralph Bakshi, dir.) – A slapstick outing about an attempted kidnapping at the Paris Opera House. A large and a short hoodlum plan to abduct the prima donna star of the performance – but first must gain entry to the theater. A sizeable amount of time is spent attempting to use a teeter-totter to catapult them to the roof. The large one jumps on one end of the board, propelling the other to the roof, carrying a heavy metal weight. Then, the little one drops the weight, with intent for it to land on the board to propel the large hood up. It does, but the little crook fails to catch the big one, who falls back on the teeter-totter, flipping the heavy weight onto his own head. They try again, with the large hood placing the teeter-totter closer to the building – and the whole building closer to the teeter-totter. He only succeeds in smacking his head on an overhanging balcony, then getting clobbered by the counterweight again. Finally, he has the little crook jump back down from the roof together with the counterweight. Their combined weight launches the large crook clear across town and into the river. They finally settle for purchasing tickets, then skulk around the building until they pass through a door – and find themselves outside the stage entrance, with the door closing and locking behind them. Another purchase of tickets. Passing through another dark doorway, the two accidentally find themselves in the spotlight on stage, and improvise a soft-shoe to beat a hasty exit. When they finally track down the singer after her performance, followed by her manager, they enter the dressing room with a large sack, but accidentally kidnap the manager instead. C’est la guerre! Four passages from various operas are included in the soundtrack, two of which I do not recognize, and leave for identification by Paul Groh or any other volunteer. The recognizable ones are the Grand March from Verdi’s “Aida” (heard over the opening credits), and “Caro Nome”, also by Verdi, from “Rigoletto”. Aside from complete versions of each opera, the Aida March was recorded electrically by Creatore’s Band on Victor, then later by Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops, on Victor red seal. The Milan Symphony Orchestra issued a European version on Columbia, and The Columbia Light Symphony Orchestra directed by Howard Barlow issued a version on British Columbia. Caro Nome made the rounds of coloraturas, including A. Michailova on early Victor black seal, Madame Tetrazzini on Gramophone Monarch, Florence Macbeth on Columbia Exclusive Artist, Amelita Galli-Curci on red seal Victor, Marion Talley on red seal Victrola, Maria Gentile on British Columbia, Thea Phillips on British Broadcast Twelve, Lina Pagliughi on Parlophone, and Lily Pons on both Victor red seal and V-Disc, to name a few.

Thus ends the last gasps of the studio Max Fleischer founded. It was a long way from Koko to Ralph Bakshi. Yet, there was still a following and a nostalgia for the studio’s early work, as denoted by the continued popularity of the old black-and white Popeyes on TV (even leading Ted Turner to issue color redrawn versions years later to keep them in syndication), and Hal Seeger’s effort to revive the “Out of the Inkwell” series in color in the 1960’s (with minor assist by Max himself). However, the studio’s execs weren’t on board with this interest in recapturing their past, and the sheer choking effect of tightening the purse strings, together with the dwindling market for theatrical product, inevitably tolled the death knell for the once-proud studio. It perhaps deserved a better send-off.

Next time we meet, a new old studio will become our focus. See you then.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

Great wrap up to a great series of posts James!

I can identify the other two passages in “The Opera Caper” for you. Like the two you recognised, they’re both by Verdi. The duet with chorus heard when the crooks enter the opera house is the Brindisi, or drinking song, from the opening of Act I of “La Traviata”, which marks the beginning of the romance between Alfredo and Violeta. (Needless to say, it doesn’t end well.) And the orchestral music we hear at the end of the cartoon is from the Overture to “La Forza del Destino”.

The opera house is obviously meant to be the Palais Garnier in Paris, even though, Paramount cartoons of the mid-1960s being what they were, the background artist was unable to capture all the elaborate detail of the building’s Second Empire style decor.

I really enjoyed this series of columns on the music of the Paramount cartoons, and I can’t wait to find out which studio you’ll be covering next. I won’t try to guess, but I’ve got my fingers crossed!

No mention of “Marvin Digs” and its’ theme song?

Bit surprised to see it not mentioned as well, as the tune itself is quite enjoyable, and the soundtrack of the short as a whole is really fun. Who knew the combination between Winston Sharples and The Life Cycle could work so well?

I was thinking the same thing. Ralph Bakshi may have hated the finished project, but the cartoon, and its music, accurately capture the zeitgeist of the hippie years.

I couldn’t find any information about “The Life Cycle” anywhere.

The Life Cycle was a short-lived band fronted by singer Verna D’Alto and guitarist Gary Wyan Lantz. Both of them were graphic artists as well as musicians, and Ralph Bakshi was a friend of theirs. After a brief career in New York, Lantz returned to his home town of Erie, Pennsylvania, and D’Alto settled in North Carolina. Lantz passed away in 2012, D’Alto in 2018.

And now we know, the rest of the story!

I think you have me confused with some other Paul….

I meant that as a joke.

So did I!

The one common thread of quality in this grab-bag of sub-par cartoons came from Winston Sharples. His music enlivens and distinguishes one cartoon I might have included here: “Sick Transit,” starring Road Hog and Rapid Rabbit (the latter spending nearly the entire picture trying to pass the slow-moving pig in his Batmobile-looking hot rod) and co-written by Bud Sagendorf (the then-current “Popeye” comic strip artist; I never liked his lumpy version of the Thimble Theater characters).

The musical–and arguably artistic–exception, “Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass Double Feature,” showcases a music style iconic to the sixties (never heard before or since) but somehow never recreated in sixties-set movies and TV shows.

Shamus Culhane’s reign–interesting how he still calls the studio “Famous” in his memoirs–resulted in marginally more interesting cartoons, but also some duds like Sir Blur (a blatant rip-off of Mister Magoo). Paramount, he wrote, kept after him to make the cartoons funnier and come up with a wacky character like Bugs Bunny; he might have responded by making a parody of a 1940s screwball cartoon to show why they didn’t work anymore.

The reason why a 1940s “screwball cartoon” wouldn’t “work anymore” is because the budget to make such a cartoon didn’t exist by then (or wouldn’t be allowed) – sadly.