1937 provided another eventful year for cartoon extremes of weather and climate conditions, though not necessarily tracking any similar events in the real world. For many studios, the season was not as flamboyant as may have been presented in the previous year. Van Buren has been squeezed out of existence by Disney’s move to RKO distribution. Lantz and Terrytoons seemed for the moment to have little concern for presenting spectacle, largely resigning themselves to the rigors of merely mass-producing product. Warner, though continuing on occasion to feature storm action in its stories, seemed content with rendering same in more simplified, less detailed form to spare expense on effects, and at times noted below, would even produce films where the weather was more mentioned by reference than visually depicted.

Even the mighty MGM contributed no new entries during this period presenting stormy skies, perhaps in growing budgetary reaction to the excesses of Harman and Ising in the previous season, which would ultimately lead to a nearly-disastrous move to all black-and-white cartoons during most of 1938, all lacking in flash or sparkle and losing the studio’s product several notches in desirability among distributors and the public. The true action during the period of this week’s survey lay with Disney, who continued to perfect realism in animation to a highly-polished degree of fine tuning, and would receive not one but two Oscars for their outstanding efforts and innovations in technology. A few surprises also arise from similar attempts at technical advances from Max Fleischer, and an “added attraction” advertising film produced by unknown artists, which demonstrates that animation may not always be the most truthful means of displaying the alleged merits of your product.

Speaking of the Weather (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 9/4/37 – Frank Tashlin, dir.), does precisely what its title suggests – speak of the weather, rather than doing much to visually depict it. The title song was a Dick Powell specialty from the picture “Gold Diggers of 1937″, which makes some incidental analogies between thunder and the beating of a heart, and lightning in a lover’s eyes. The number is performed in the cartoon by caricatures of the Boswell Sisters, on the cover of Radioland magazine, one of a countless number of magazines depicted in the rack of a drug store, within which nearly all of the action of the film takes place. (The film was part of a trilogy of titles produced by Tashlin utilizing the tried and true “everything-comes-to-life-at-midnight” formula previously exploited by Harman and Ising in such titles as “I Like Mountain Music”, though one can easily notice Tashlin’s improvement on the premise by tighter timing and wittier gags.) The only actual rain seen in the film appears in an introduction to the featured song, depicting a magazine cover picture of Leopold Stokowski, who opens his sheet music to the pages of the Storm segment of the William Tell Overture, upon which a steady stream of raindrops is already falling, causing Leopold to press a button on his music stand to activate a windshield wiper over the pages to keep the notes visible while he conducts. Leopold notably includes motions within his conducting more intended to wring water out of his long hair than to actually lead the unseen orchestra.

Speaking of the Weather (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 9/4/37 – Frank Tashlin, dir.), does precisely what its title suggests – speak of the weather, rather than doing much to visually depict it. The title song was a Dick Powell specialty from the picture “Gold Diggers of 1937″, which makes some incidental analogies between thunder and the beating of a heart, and lightning in a lover’s eyes. The number is performed in the cartoon by caricatures of the Boswell Sisters, on the cover of Radioland magazine, one of a countless number of magazines depicted in the rack of a drug store, within which nearly all of the action of the film takes place. (The film was part of a trilogy of titles produced by Tashlin utilizing the tried and true “everything-comes-to-life-at-midnight” formula previously exploited by Harman and Ising in such titles as “I Like Mountain Music”, though one can easily notice Tashlin’s improvement on the premise by tighter timing and wittier gags.) The only actual rain seen in the film appears in an introduction to the featured song, depicting a magazine cover picture of Leopold Stokowski, who opens his sheet music to the pages of the Storm segment of the William Tell Overture, upon which a steady stream of raindrops is already falling, causing Leopold to press a button on his music stand to activate a windshield wiper over the pages to keep the notes visible while he conducts. Leopold notably includes motions within his conducting more intended to wring water out of his long hair than to actually lead the unseen orchestra.

I Wanna Be a Sailor (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 9/25/37 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir,) – This one goes in for considerably more weather action than the preceding title, though one has to say that the motion of water and waves is presented in rather “toony” form rather than aiming for spectacular realism – so that the animation probably stayed well within budget. A mother parrot in a cage tutors her three offspring in the fine arts of parrotry – mainly, how to say “Polly wants a cracker.” However, her son, a young salt who sports a sailor’s cap, takes after his old man, and wants nothing to do with eating crackers, but longs to lead a life of adventure as captain of a ship, roaming the world in search of fame and fortune. Mother is aghast at this attitude, and recounts the tale of how Pop’s wandering ways broke up the family by his refusing to stay anchored in one harbor for more than five minutes – resulting in him deserting Mom and the brood, never to return. Junior pays this story no mind, and causes Mom to keel over in a faint when he surprisingly reaffirms his wish to be a sailor. Taking advantage of Mom’s temporary incapacity, Junior sets out into the world, finding an old barrel, which he cuts in half to privide the hull for a makeshift pirate ship. A young duck with an unstoppable gift of gab observes the parrot’s construction activities, and volunteers to sign on as crew. The vessel sets sail, powered by a steady breeze caught by a suit of red flannel underwear tied to the spars instead of a canvas sail.

I Wanna Be a Sailor (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 9/25/37 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir,) – This one goes in for considerably more weather action than the preceding title, though one has to say that the motion of water and waves is presented in rather “toony” form rather than aiming for spectacular realism – so that the animation probably stayed well within budget. A mother parrot in a cage tutors her three offspring in the fine arts of parrotry – mainly, how to say “Polly wants a cracker.” However, her son, a young salt who sports a sailor’s cap, takes after his old man, and wants nothing to do with eating crackers, but longs to lead a life of adventure as captain of a ship, roaming the world in search of fame and fortune. Mother is aghast at this attitude, and recounts the tale of how Pop’s wandering ways broke up the family by his refusing to stay anchored in one harbor for more than five minutes – resulting in him deserting Mom and the brood, never to return. Junior pays this story no mind, and causes Mom to keel over in a faint when he surprisingly reaffirms his wish to be a sailor. Taking advantage of Mom’s temporary incapacity, Junior sets out into the world, finding an old barrel, which he cuts in half to privide the hull for a makeshift pirate ship. A young duck with an unstoppable gift of gab observes the parrot’s construction activities, and volunteers to sign on as crew. The vessel sets sail, powered by a steady breeze caught by a suit of red flannel underwear tied to the spars instead of a canvas sail.

The parrot compares this picture to “Mutiny on the County”, playing on Clark Gable’s recent success in the similarly-named MGM feature about the “Bounty”. As the parrot climbs the mast to act as lookout, a black cloud rolls into the skies, then the scene is shattered by a lightning flash, the bolt splitting and reshaping itself in form to spell out the word “BAM.” The parrot panics, running around the deck, and orders the duck to do something. “What for? I like the water”, responds the duck, then rambles on in endless speech about all the fun things he loves to do when it’s wet, only pausing in breath for a moment to turn to the audience and add “Ain’t I the talkingest little guy?” The red flannel sail begins to lose its functionality, as its drop seat is blown open by the storm’s force. The driving rain rocks the ship, and the parrot us unable to keep the ship’s wheel from spinning – and spins around right along with it. The pitching deck has a strange effect on a can of red paint, which topples sideways, spilling its contents out in a downward flow while the ship maintains one extreme degree of listing, then regaining all the paint back into the can whenever the shop tips the other direction. Through all this, the duck struts fearlessly back and forth across the deck. beating his chest and taking deep breaths to obtain the full effect of being in his rainy element, and enjoying himself immensely. The parrot tries to throw out the anchor – but only rips off the stern of the ship to which it is tied to. The barrel begins to sink, and both the duck and the parrot leap into the water. But the parrot doesn’t know how to swim, and cries for help, reaching for and clinging to the duck. The duck socks the parrot in the jaw to render him briefly unconscious and control his fit of fear, then calmly tosses the parrot up upon the shore, adding as he departs, “You big sissy.” Mama parrot, having heard the screams, catches up with Junior, and again asks him, “Now, you don’t want to be a sailor, do you?” Weeping, the parrot seems about to agree with mother, then utters the unexpected response “Yes” again, causing his mother to faint for the second time. But before the film closes, Mom raises her head, and asks the audience, “Now what would you do with a child like that?”

The parrot compares this picture to “Mutiny on the County”, playing on Clark Gable’s recent success in the similarly-named MGM feature about the “Bounty”. As the parrot climbs the mast to act as lookout, a black cloud rolls into the skies, then the scene is shattered by a lightning flash, the bolt splitting and reshaping itself in form to spell out the word “BAM.” The parrot panics, running around the deck, and orders the duck to do something. “What for? I like the water”, responds the duck, then rambles on in endless speech about all the fun things he loves to do when it’s wet, only pausing in breath for a moment to turn to the audience and add “Ain’t I the talkingest little guy?” The red flannel sail begins to lose its functionality, as its drop seat is blown open by the storm’s force. The driving rain rocks the ship, and the parrot us unable to keep the ship’s wheel from spinning – and spins around right along with it. The pitching deck has a strange effect on a can of red paint, which topples sideways, spilling its contents out in a downward flow while the ship maintains one extreme degree of listing, then regaining all the paint back into the can whenever the shop tips the other direction. Through all this, the duck struts fearlessly back and forth across the deck. beating his chest and taking deep breaths to obtain the full effect of being in his rainy element, and enjoying himself immensely. The parrot tries to throw out the anchor – but only rips off the stern of the ship to which it is tied to. The barrel begins to sink, and both the duck and the parrot leap into the water. But the parrot doesn’t know how to swim, and cries for help, reaching for and clinging to the duck. The duck socks the parrot in the jaw to render him briefly unconscious and control his fit of fear, then calmly tosses the parrot up upon the shore, adding as he departs, “You big sissy.” Mama parrot, having heard the screams, catches up with Junior, and again asks him, “Now, you don’t want to be a sailor, do you?” Weeping, the parrot seems about to agree with mother, then utters the unexpected response “Yes” again, causing his mother to faint for the second time. But before the film closes, Mom raises her head, and asks the audience, “Now what would you do with a child like that?”

The Case of the Stuttering Pig (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky Pig), 10/30/37 – Frank Tashlin dir.), uses weather only briefly for appropriate atmospherics, in another tale of haunting adventure and mystery. The grounds of an old walled estate are enveloped in a raging thunderstorm, as lightning flashes regularly change the skies from alternating black shadows to blazing white light. The gates of the estate rattle, and the limbs of leafless trees flail in the wind. Shutters blow open and shut against the window frames, as the storm theme from the William Tell Overture predominates over the opening credits and introductory scenes. Inside, things are, in contrast, almost as quiet as a church, with only the ticking of an old pendulum clock punctuating the silence. A sextet of pigs, including Porky, Petunia, and four heretofore unknown relatives (Patrick, Peter, Percy, and Portus) all sit in chairs, nervously trembling in apprehension of the evening’s events, awaiting the arrival of lawyer Goodwill to read the will of the late Solomon Swine (a portly pig whose picture on the wall bears a striking resemblance to Oliver Hardy). Goodwill blows in the door as if jet-propelled by the storm outside, then reveals the contents of the will, leaving the estate to the six pigs, but with a proviso that in the event of their demise, the entire estate will revert to Goodwill. “But nothing will happen – I hope”, utters Goodwill in tones that lack conviction, and he departs from the premises. Or so it appears, as he waits his chance when no one is looking, to slip around to a cellar door, and enter a secret laboratory hidden in the basement. There, he changes into a black overcoat, then fills a beaker with a goodly dose of Jekyll and Hyde Juice. He downs a swallow of the stuff, then begins breathing heavily as the camera closes in – but nothing! He’s forgotten one step in the chemical process, and places the chemical cocktail into a milk shake machine for thorough mixing. Another swallow has the desired effect, transforming him into a towering, hideous monster. He begins ranting of his intentions to do the pigs in, conversing in break-the-fourth-wall fashion with the audience, and choosing to demonstrate his evil attitude by picking out an unseen theater patron identified as sitting in the third row, and jeering insults at him, such as referring to him as a “cream puff”. Tashlin demonstrates his love of unusual camera angles, animating the villain in camera extremes that nearly make him loom out of the frame with his face eye to eye with the camera kens, as if he is ready to reach out and grab you. The pigs begin to disappear one by one, leaving Porky as last man standing, while the remaining family members are locked in stocks in the laboratory, to await the capture of Porky before Goodwill does them in. Chase and fright gags provide most of the remaining content of the film, one notable scene having Porky attempt to elude the villain by climbing four sets of staircases in super-speed action, only to leap straight into the arms of the villain, already awaiting his arrival on the top floor. Porky eventually discovers the hidden lab, and releases his family from the stocks, only to have Goodwill trap them in a corner, intent on carrying out his threat to bring about their doom. Rescue comes from an unexpected source, as a theater seat is suddenly thrown into the screen from the foreground, knocking the villain backwards to be trapped in the stocks. “Who did that”, ask the pigs. “Me!”, shouts an aggressive, angered voice. “I’m the guy in the third row”, he concludes, as the defeated Goodwill scowls in his imprisoned state, for the iris out.

The Case of the Stuttering Pig (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky Pig), 10/30/37 – Frank Tashlin dir.), uses weather only briefly for appropriate atmospherics, in another tale of haunting adventure and mystery. The grounds of an old walled estate are enveloped in a raging thunderstorm, as lightning flashes regularly change the skies from alternating black shadows to blazing white light. The gates of the estate rattle, and the limbs of leafless trees flail in the wind. Shutters blow open and shut against the window frames, as the storm theme from the William Tell Overture predominates over the opening credits and introductory scenes. Inside, things are, in contrast, almost as quiet as a church, with only the ticking of an old pendulum clock punctuating the silence. A sextet of pigs, including Porky, Petunia, and four heretofore unknown relatives (Patrick, Peter, Percy, and Portus) all sit in chairs, nervously trembling in apprehension of the evening’s events, awaiting the arrival of lawyer Goodwill to read the will of the late Solomon Swine (a portly pig whose picture on the wall bears a striking resemblance to Oliver Hardy). Goodwill blows in the door as if jet-propelled by the storm outside, then reveals the contents of the will, leaving the estate to the six pigs, but with a proviso that in the event of their demise, the entire estate will revert to Goodwill. “But nothing will happen – I hope”, utters Goodwill in tones that lack conviction, and he departs from the premises. Or so it appears, as he waits his chance when no one is looking, to slip around to a cellar door, and enter a secret laboratory hidden in the basement. There, he changes into a black overcoat, then fills a beaker with a goodly dose of Jekyll and Hyde Juice. He downs a swallow of the stuff, then begins breathing heavily as the camera closes in – but nothing! He’s forgotten one step in the chemical process, and places the chemical cocktail into a milk shake machine for thorough mixing. Another swallow has the desired effect, transforming him into a towering, hideous monster. He begins ranting of his intentions to do the pigs in, conversing in break-the-fourth-wall fashion with the audience, and choosing to demonstrate his evil attitude by picking out an unseen theater patron identified as sitting in the third row, and jeering insults at him, such as referring to him as a “cream puff”. Tashlin demonstrates his love of unusual camera angles, animating the villain in camera extremes that nearly make him loom out of the frame with his face eye to eye with the camera kens, as if he is ready to reach out and grab you. The pigs begin to disappear one by one, leaving Porky as last man standing, while the remaining family members are locked in stocks in the laboratory, to await the capture of Porky before Goodwill does them in. Chase and fright gags provide most of the remaining content of the film, one notable scene having Porky attempt to elude the villain by climbing four sets of staircases in super-speed action, only to leap straight into the arms of the villain, already awaiting his arrival on the top floor. Porky eventually discovers the hidden lab, and releases his family from the stocks, only to have Goodwill trap them in a corner, intent on carrying out his threat to bring about their doom. Rescue comes from an unexpected source, as a theater seat is suddenly thrown into the screen from the foreground, knocking the villain backwards to be trapped in the stocks. “Who did that”, ask the pigs. “Me!”, shouts an aggressive, angered voice. “I’m the guy in the third row”, he concludes, as the defeated Goodwill scowls in his imprisoned state, for the iris out.

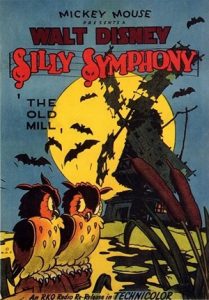

The Old Mill (Disney/RKO, Silly Symphony, 11/5/37, Wilfred Jackson, dir.) – Another Disney Oscar winner, and perhaps one of the most deserved artistically. There is not really a plot, but more a scenario. A chronicle of a 24 hour period at an abandoned windmill, that seems to have done service as a grinding mill in its better days. Now, the mill is old and forgotten, without a human in sight. But it is far from empty, despite its somewhat dilapidated state. An entire ecosystem of animals and birds have taken up residence within its walls. In its nooks and crannies can be found cooing turtle doves, curious field mice, a pair of bluebirds who are tending to a nest of unhatched eggs built into one of the recesses of the mill’s turntable supporting a massive wooden cogwheel, a wise old owl, and a flock of bats who live upside down in the mill’s uppermost rafters. Add to these an incidental exterior sideshow of grazing cattle, ducks gliding on water, a busy web-building spider, and a nighttime of entertainment from conversing frogs, chirping crickets and glowing fireflies. But the real star of the show is Ub Iwerks’ multiplane camera, a device first used in experimental form at Iwerks’ own studio, but now refined into a multi-story tower of layered cel and glass work, to create an amazing perspective depth illusion for actual flat artwork, moved relative to one another in sunchonous perfection to approximate respective distances of objects from the camera. This would be Disney’s first publicly-seen proving ground for the device (it was not ready in time to be utilized in the filming of “Snow White”), and from the opening shot of the film produces startling realism, including the ability for the camera to move through and past a shimmering spider web across the foreground of the shot, the web’s image disappearing from the shot as if softly fading out of the focal range of the camera lens. Original audiences – and the Academy – must have been in awe.

The Old Mill (Disney/RKO, Silly Symphony, 11/5/37, Wilfred Jackson, dir.) – Another Disney Oscar winner, and perhaps one of the most deserved artistically. There is not really a plot, but more a scenario. A chronicle of a 24 hour period at an abandoned windmill, that seems to have done service as a grinding mill in its better days. Now, the mill is old and forgotten, without a human in sight. But it is far from empty, despite its somewhat dilapidated state. An entire ecosystem of animals and birds have taken up residence within its walls. In its nooks and crannies can be found cooing turtle doves, curious field mice, a pair of bluebirds who are tending to a nest of unhatched eggs built into one of the recesses of the mill’s turntable supporting a massive wooden cogwheel, a wise old owl, and a flock of bats who live upside down in the mill’s uppermost rafters. Add to these an incidental exterior sideshow of grazing cattle, ducks gliding on water, a busy web-building spider, and a nighttime of entertainment from conversing frogs, chirping crickets and glowing fireflies. But the real star of the show is Ub Iwerks’ multiplane camera, a device first used in experimental form at Iwerks’ own studio, but now refined into a multi-story tower of layered cel and glass work, to create an amazing perspective depth illusion for actual flat artwork, moved relative to one another in sunchonous perfection to approximate respective distances of objects from the camera. This would be Disney’s first publicly-seen proving ground for the device (it was not ready in time to be utilized in the filming of “Snow White”), and from the opening shot of the film produces startling realism, including the ability for the camera to move through and past a shimmering spider web across the foreground of the shot, the web’s image disappearing from the shot as if softly fading out of the focal range of the camera lens. Original audiences – and the Academy – must have been in awe.

The first half of the film is a camera tour of the mill, its surroundings, and its inhabitants, with little happening in terms of events except the falling of night, and the sounds of nature’s chatterboxes as frogs croak and crickets rub their legs in conversation with one another. A rising wind, however, sends a chill into the air, and causes the insects to disperse, and the frogs to huddle together under the protection of a lily pad in the pond. Rows of bullrushes are bent to tap upon hollow reeds, playing a staccato marimba overture. Intersecting layers of dark clouds from various elevations cross in the sky behind the outline of the mill’s arms. The blades of the windmill’s arms begin to creak, and strain repeatedly to commence turning, only to be repeatedly stopped in their progress, by a thick restraining rope which has been places across the central gears and drive-shaft to keep the blades from purposeless rotation in their present state of idleness. However, this night’s wind is of unusually substantial force, and within the structure, the owl struggles to maintain a perch upon spokes fastened on the inner side of the cogwheel, which keep changing position from partial rotation of the wheel. And the mother bluebird watches from the nest with fear in her eyes, observing the severe strain being placed upon the strands of the restraining rope. Suddenly, the unexpected happens – the rope snaps, setting the machinery of the mill free to do the wind’s bidding. With no braking mechanism in place to establish control, the turntable begins a counterclockwise spin to match the rotation of the vertically-rotating cogwheel. The owl can no longer maintain a footing on the spokes, and is forced to flap his way to the upper rafters, where the bats have temporarily left empty perching areas while out upon their nightly hunting rounds. The mother bluebird remains in peril, as the gear teeth of the cogwheel propel the turntable surface containing her eggs closer and closer to intersection with the path of the cogwheel.

The first half of the film is a camera tour of the mill, its surroundings, and its inhabitants, with little happening in terms of events except the falling of night, and the sounds of nature’s chatterboxes as frogs croak and crickets rub their legs in conversation with one another. A rising wind, however, sends a chill into the air, and causes the insects to disperse, and the frogs to huddle together under the protection of a lily pad in the pond. Rows of bullrushes are bent to tap upon hollow reeds, playing a staccato marimba overture. Intersecting layers of dark clouds from various elevations cross in the sky behind the outline of the mill’s arms. The blades of the windmill’s arms begin to creak, and strain repeatedly to commence turning, only to be repeatedly stopped in their progress, by a thick restraining rope which has been places across the central gears and drive-shaft to keep the blades from purposeless rotation in their present state of idleness. However, this night’s wind is of unusually substantial force, and within the structure, the owl struggles to maintain a perch upon spokes fastened on the inner side of the cogwheel, which keep changing position from partial rotation of the wheel. And the mother bluebird watches from the nest with fear in her eyes, observing the severe strain being placed upon the strands of the restraining rope. Suddenly, the unexpected happens – the rope snaps, setting the machinery of the mill free to do the wind’s bidding. With no braking mechanism in place to establish control, the turntable begins a counterclockwise spin to match the rotation of the vertically-rotating cogwheel. The owl can no longer maintain a footing on the spokes, and is forced to flap his way to the upper rafters, where the bats have temporarily left empty perching areas while out upon their nightly hunting rounds. The mother bluebird remains in peril, as the gear teeth of the cogwheel propel the turntable surface containing her eggs closer and closer to intersection with the path of the cogwheel.

Rather than abandon the nest for her own safety, the brave mother places herself as a shield over the nest, facing head on the approach of the giant gear, in what seems a selfless recipe for suicide and hopeless sacrifice. But a fortunate miracle changes the situation – one of the gear teeth of the cogwheel is missing, and a large open hole remains where the huge wooden peg that previously served as a gear tooth had once been implanted. The mother and nest go under the wheel – but emerge on the other side, unscarred, having just fit into the recess of the peg hole during the cogwheel’s rotation. But will they be so lucky a second time, as the turntable spins another full rotation, and the nest approaches the wheel again. Yes, saints be praised, for it appears that the cogwheel and turntable are engineered with a matching number of gear pegs and turntable holes, so that the nest hits the same open hole upon every revolution. Mama and eggs are physically safe for the moment, though forced to endure a horrendous and dizzying merry-go-round ride. The elements continue to beat down upon the mill’s exterior. Raindrops pelt and bounce off of the tattered roof shingles. Shutters make the sound of cymbal crashes as they alternatingly fly open and slam shut at an upper-story window. The owl attempts to dodge intermittent raindrops falling through the leaking roof, then is thoroughly doused as several shingles break away, his normally puffy feathers reduced to a thin, drooping soggy state clinging to his body, and leaving the noble bird in a mood of considerable embarrassment. The turtle dove huddle together to shield each other from the wind and lightning, while the field mice peer with glowing eyes at the storm outside from the safety of a hole at a lower elevation. Outside, a hollow tree provides a path for wind flow that produces sounds like the singing of a ghostly chorus, while several reeds snap at right-angles, becoming flutes for the breezes to play. The tempo of everything quickens, as the storm grows in intensity. The windmill’s arms accelerate to a violent and fearsome RPM rate, their blades bending and arching into curves approaching the limits of their wooden frames. She shutter is smashed against the window frame, its boards splitting from one another and dropping away to the ground. Shingles fly, rafters rattle, and the inner wheels spin furiously, as if about to fall off their mountings. The wonderfully dramatic music score mounts to a crescendo in volume and pitch, as a montage of views of everything taking place within and without quickens in cuts to shots of less than half a second, yet in well-chosen angles that allow the audience to fully follow the action. Then, with the crash of percussion on the track, the skies virtually transform entirely to electric white, as a massive lightning bolt strikes the roof of the mill. Most of one blade is blasted away from the windmill’s arms, causing an imbalance upon the drive shaft which stop’s the blades from turning when it reaches a point where the wind propulsion will no longer force the defective blade over the top. The mid-level walls of the structure are also cracked, causing the upper portions of the tower to lean backwards, coming to rest in an off-kilter angle roughly resembling a reverse Tower of Pisa. While segments of its walls and roof remain reasonably solid, the mechanisms of the mill are rendered beyond repair, and it is evident that the mill’s blades will never run again.

Rather than abandon the nest for her own safety, the brave mother places herself as a shield over the nest, facing head on the approach of the giant gear, in what seems a selfless recipe for suicide and hopeless sacrifice. But a fortunate miracle changes the situation – one of the gear teeth of the cogwheel is missing, and a large open hole remains where the huge wooden peg that previously served as a gear tooth had once been implanted. The mother and nest go under the wheel – but emerge on the other side, unscarred, having just fit into the recess of the peg hole during the cogwheel’s rotation. But will they be so lucky a second time, as the turntable spins another full rotation, and the nest approaches the wheel again. Yes, saints be praised, for it appears that the cogwheel and turntable are engineered with a matching number of gear pegs and turntable holes, so that the nest hits the same open hole upon every revolution. Mama and eggs are physically safe for the moment, though forced to endure a horrendous and dizzying merry-go-round ride. The elements continue to beat down upon the mill’s exterior. Raindrops pelt and bounce off of the tattered roof shingles. Shutters make the sound of cymbal crashes as they alternatingly fly open and slam shut at an upper-story window. The owl attempts to dodge intermittent raindrops falling through the leaking roof, then is thoroughly doused as several shingles break away, his normally puffy feathers reduced to a thin, drooping soggy state clinging to his body, and leaving the noble bird in a mood of considerable embarrassment. The turtle dove huddle together to shield each other from the wind and lightning, while the field mice peer with glowing eyes at the storm outside from the safety of a hole at a lower elevation. Outside, a hollow tree provides a path for wind flow that produces sounds like the singing of a ghostly chorus, while several reeds snap at right-angles, becoming flutes for the breezes to play. The tempo of everything quickens, as the storm grows in intensity. The windmill’s arms accelerate to a violent and fearsome RPM rate, their blades bending and arching into curves approaching the limits of their wooden frames. She shutter is smashed against the window frame, its boards splitting from one another and dropping away to the ground. Shingles fly, rafters rattle, and the inner wheels spin furiously, as if about to fall off their mountings. The wonderfully dramatic music score mounts to a crescendo in volume and pitch, as a montage of views of everything taking place within and without quickens in cuts to shots of less than half a second, yet in well-chosen angles that allow the audience to fully follow the action. Then, with the crash of percussion on the track, the skies virtually transform entirely to electric white, as a massive lightning bolt strikes the roof of the mill. Most of one blade is blasted away from the windmill’s arms, causing an imbalance upon the drive shaft which stop’s the blades from turning when it reaches a point where the wind propulsion will no longer force the defective blade over the top. The mid-level walls of the structure are also cracked, causing the upper portions of the tower to lean backwards, coming to rest in an off-kilter angle roughly resembling a reverse Tower of Pisa. While segments of its walls and roof remain reasonably solid, the mechanisms of the mill are rendered beyond repair, and it is evident that the mill’s blades will never run again.

Dawn breaks on the scene. The storm has subsided and moved on. The bats return from wherever they had huddled during the night fury of the storm outside. Life begins to return to normal, as the owl adjusts to his new higher perching place, the turtle doves continue tto bill and coo, and below, the bluebirds celebrate the miracle of life, as they go about finding food for their newly-hatched nest of chicks. The camera pulls back to approximately where the episode began, with the image of the old mill, battered, misshapen and bent, but still glowing amidst the amber light of a sunlit sky.

For eight minutes, we have truly known a Disney world in vivid detail like never before. This enchanting masterpiece never ceases to immerse its audiences by transporting them into an encompassing realm of realism crossed with fantasy, and remains a timeless mainstay in defining the Disney brand.

Released on the same day as the precious classic was Columbia’s The Little Match Girl (Color Rhapsodies. 7/5/37 – Art Davis, dir.) This film has been extensively reviewed by other authors, and, because of its sparse use of anything weather-related, will not be elaborated upon heavily here. It is in fact unknown if what appears to be a windstorm is a part of the little girl’s smoke dream, or something that really occurred in her back-alley resting place during the night. Perhaps it is only the reaction of her mind to the drop in heat of the lone match providing her warmth, in its final stages before puffing out. Whatever the cause, just as her dreams of walking with cherubic angels, receiving lovely clothes, a doll, and warming food, build to a height of happiness that brings tears to her eyes, a destructive wind scatters the angels, unwraps and destroys toy boxes, unravels the girl’s doll, and topples marble columns and statuary, leaving nothing but a darkened sky, and the light of a single candle, distanced considerably from the girl. She struggles and stumbles to make her way toward the candle, her hands outstretched to embrace its warmth – but collapses inches short of reaching her goal. The camera dissolves back to the real world, to find her, face down and lifeless in the snow, next to the last burnt-out matchstick. A guardian angel descends from the heavens, lifting the transparent soul of the girl into its arms, and flies her off into a star-studded sky, as bells of the holiday continue to peal for the iris out. An unusual and tragic cartoon, but one which suffers most from its deficiencies in artwork (character design flaws, and an aggravating tendency to fall back on repeating animation cycles to save on budget). It might have turned out much better if the art and directing skills of Disney or MGM could have been coupled with not doctoring the script to provide the “happy ending” such other studios were used to. (Of course, Hugh Harman would demonstrate his skill at tackling a not-so-happy ending a few seasons later with “Peace On Earth”, so perhaps the unlikely combining of his skills with the Columbia project could have produced a more timeless masterpiece.) Oh, well – that can be our smoke dream for some lonely Christmas or New Years’ Eve.

Released on the same day as the precious classic was Columbia’s The Little Match Girl (Color Rhapsodies. 7/5/37 – Art Davis, dir.) This film has been extensively reviewed by other authors, and, because of its sparse use of anything weather-related, will not be elaborated upon heavily here. It is in fact unknown if what appears to be a windstorm is a part of the little girl’s smoke dream, or something that really occurred in her back-alley resting place during the night. Perhaps it is only the reaction of her mind to the drop in heat of the lone match providing her warmth, in its final stages before puffing out. Whatever the cause, just as her dreams of walking with cherubic angels, receiving lovely clothes, a doll, and warming food, build to a height of happiness that brings tears to her eyes, a destructive wind scatters the angels, unwraps and destroys toy boxes, unravels the girl’s doll, and topples marble columns and statuary, leaving nothing but a darkened sky, and the light of a single candle, distanced considerably from the girl. She struggles and stumbles to make her way toward the candle, her hands outstretched to embrace its warmth – but collapses inches short of reaching her goal. The camera dissolves back to the real world, to find her, face down and lifeless in the snow, next to the last burnt-out matchstick. A guardian angel descends from the heavens, lifting the transparent soul of the girl into its arms, and flies her off into a star-studded sky, as bells of the holiday continue to peal for the iris out. An unusual and tragic cartoon, but one which suffers most from its deficiencies in artwork (character design flaws, and an aggravating tendency to fall back on repeating animation cycles to save on budget). It might have turned out much better if the art and directing skills of Disney or MGM could have been coupled with not doctoring the script to provide the “happy ending” such other studios were used to. (Of course, Hugh Harman would demonstrate his skill at tackling a not-so-happy ending a few seasons later with “Peace On Earth”, so perhaps the unlikely combining of his skills with the Columbia project could have produced a more timeless masterpiece.) Oh, well – that can be our smoke dream for some lonely Christmas or New Years’ Eve.

Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves (Fleischer/Paramount, 2 reel “Color Feature”, 11/26/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/George Germanetti/Orestes Calpini, anim.), features a short sequence where Popeye and his friends face the rigors and \ temperature extremes of the desert. Popeye, assigned to Coast Guard duty, maintains a sentry watch at a pier while entertaining his girlfriend Olive with occasional kisses. Popeye’s crew consists of Wimpy, who occupies himself eating hamburgers while on the deck of an exotic flying boat – half ship, half airplane. A radio distress call alerts the boys that Abu Hassan the bandit and his legion of thieves are on a rampage of pillage and destruction, at an undisclosed position somewhere “That-a-way”. Popeye revs up the ship’s engines while Olive, determined not to be left behind, hangs onto the ship’s mooring tope as it takes off into the skies, dragging her along. A shot of the globe shows Popeye aimlessly searching the continents on either side of the Atlantic Ocean, as Popeye mutters about checking “across the street”, and also uses the phrase “Skip the gutter”. Suddenly, the plane/ship’s motor gives out, and Popeye borrows a catch-phrase from bandleader Kay Kyser – “Something is definitely wrong. I’m right, it’s wrong!” The vessel crashes into a sand dune in the middle of an Arabian desert. Our three travelers trudge through the burning sun of the day and on through the dead of night across the endless sands, depicted in realistic detail with three-dimensional models on the turntable camera, an occasional set of bleached animal-skeleton bones passing before the camera in the foreground. Popeye comments that he’d love to make a sand-wich, if he could only find a witch. The famished Wimpy, however, has got it bad from the effects of the heat, and spots what appears to be a table under a shady palm, laden with a banquet. “Food!”, he cries, and leaps for the table – which disappears on cue, being nothing but a mirage. “A bitter disappointment”, grumbles Wimpy. He rejoins his comrades in their aimless trek. It is unclear whether what they see next is another mirage or real, but a giant mechanical stop signal suddenly appears upon the sand ahead. Its glowing light (another 3-D model) changes from green to red. Popeye and company take the opportunity for a rest break on the ground as they wait for the light to change, then proceed ahead when the signal turns green. Olive is the next to suffer, falling flat on her face in complete collapse. Popeye lifts her into a position where she appears to be walking like a quadruped, her back oddly curved as if forming the shape of camel humps. The conversion does not help Olive’s “vitaliky”, and not only she, but Wimpy also, collapse simultaneously. Popeye vows to get them out of this desert somehow, and positions his friends and himself so that the three of them form a loop grasping the ankles of the other, but rather than a wheel, assume the cornered angles of WWI tank treads. “I tank we go now”, quips Popeye, as the three roll over the sand with the clanking sounds of rumbling metal, rolling down a slope to the borders of a walled town, in which Popeye locates a well from which to pump water on his friends to revive them. From here, the well-remembered quest for bandits can go on.

Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves (Fleischer/Paramount, 2 reel “Color Feature”, 11/26/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/George Germanetti/Orestes Calpini, anim.), features a short sequence where Popeye and his friends face the rigors and \ temperature extremes of the desert. Popeye, assigned to Coast Guard duty, maintains a sentry watch at a pier while entertaining his girlfriend Olive with occasional kisses. Popeye’s crew consists of Wimpy, who occupies himself eating hamburgers while on the deck of an exotic flying boat – half ship, half airplane. A radio distress call alerts the boys that Abu Hassan the bandit and his legion of thieves are on a rampage of pillage and destruction, at an undisclosed position somewhere “That-a-way”. Popeye revs up the ship’s engines while Olive, determined not to be left behind, hangs onto the ship’s mooring tope as it takes off into the skies, dragging her along. A shot of the globe shows Popeye aimlessly searching the continents on either side of the Atlantic Ocean, as Popeye mutters about checking “across the street”, and also uses the phrase “Skip the gutter”. Suddenly, the plane/ship’s motor gives out, and Popeye borrows a catch-phrase from bandleader Kay Kyser – “Something is definitely wrong. I’m right, it’s wrong!” The vessel crashes into a sand dune in the middle of an Arabian desert. Our three travelers trudge through the burning sun of the day and on through the dead of night across the endless sands, depicted in realistic detail with three-dimensional models on the turntable camera, an occasional set of bleached animal-skeleton bones passing before the camera in the foreground. Popeye comments that he’d love to make a sand-wich, if he could only find a witch. The famished Wimpy, however, has got it bad from the effects of the heat, and spots what appears to be a table under a shady palm, laden with a banquet. “Food!”, he cries, and leaps for the table – which disappears on cue, being nothing but a mirage. “A bitter disappointment”, grumbles Wimpy. He rejoins his comrades in their aimless trek. It is unclear whether what they see next is another mirage or real, but a giant mechanical stop signal suddenly appears upon the sand ahead. Its glowing light (another 3-D model) changes from green to red. Popeye and company take the opportunity for a rest break on the ground as they wait for the light to change, then proceed ahead when the signal turns green. Olive is the next to suffer, falling flat on her face in complete collapse. Popeye lifts her into a position where she appears to be walking like a quadruped, her back oddly curved as if forming the shape of camel humps. The conversion does not help Olive’s “vitaliky”, and not only she, but Wimpy also, collapse simultaneously. Popeye vows to get them out of this desert somehow, and positions his friends and himself so that the three of them form a loop grasping the ankles of the other, but rather than a wheel, assume the cornered angles of WWI tank treads. “I tank we go now”, quips Popeye, as the three roll over the sand with the clanking sounds of rumbling metal, rolling down a slope to the borders of a walled town, in which Popeye locates a well from which to pump water on his friends to revive them. From here, the well-remembered quest for bandits can go on.

A Ride For Cinderella (Jam Handy, 12/2/37 – credits unknown) – The second in an elaborate series of Technicolor “soft-sell” advertising films paid for by Chevrolet as a means of promoting its tall, blocky sedans that probably got next-to-no gas mileage from their sheer weight in cast-iron (but of course, in a day when gasoline cost pennies a gallon, who cared?) I would love to see animator breakdowns and director credits turn up for these lovely films, which appeared over the course of the series to be the work of diverse hands, likely moonlighting from multiple major studios or between jobs at them. Later installments in the series exhibited strong resemblance to the styles of the abandoned MGM units that had produced “Captain and the Kids” cartoons (“Peg Leg Pedro”) and Walter Lantz (“The Princess and the Pauper”), the latter title also featuring some identifiable work of Jim Tyer between studio gigs. The short here being reviewed gives me the impression of heavy influence from the artists of the former Van Buren studio, benefitting immensely from their retooling in art training under the former direction of Burt Gilette and experience in Technicolor animation, who would have been looking for new work about this time. Many character designs, both of the humans and of the principal “star”, an elf who eventually became known as Nicky Nome, are similar enough in simple line design and rounded cheek features to suggest characters out of “Bold King Cole”, “A Waif’s Welcome”, and the like. But there are also other possible influences about, and some techniques which may be unique to this production. Possible MGM influence may be evidenced by a hound character, who is not too far distant from canines who appeared in MGM’s animation of the redesigned Bruno for the Bosko series, or from canines appearing in “The Pups’ Picnic” or “The Wayward Pups”, suggesting that some of Harman and Ising’s men may have moved on. A witch character is also somewhat MGM-like in design, though one special-effects technique (in a scene where she informs the audience that she even hates herself, demonstrated by delivering a lighting-force right cross to her own jaw) is one that does not appear to be recognizable as a signature effect of any other studio. And a group of cloudy evil spirits from the witch’s brew strongly suggest a cross between old man winter from “To Spring” and the spirits of ammonia from “Bottles”, also potentially giving away ex-MGM handiwork. One other design, of a well-animated female rabbit switchboard operator, is a mystery to place, as she seems a cross between the bunny designs from the girls’ school in Disney’s “The Tortoise and the Hare” and the rabbits in Fleischer’s “Bunny-Mooning”, leaving it anybody’s guess who created her.

A Ride For Cinderella (Jam Handy, 12/2/37 – credits unknown) – The second in an elaborate series of Technicolor “soft-sell” advertising films paid for by Chevrolet as a means of promoting its tall, blocky sedans that probably got next-to-no gas mileage from their sheer weight in cast-iron (but of course, in a day when gasoline cost pennies a gallon, who cared?) I would love to see animator breakdowns and director credits turn up for these lovely films, which appeared over the course of the series to be the work of diverse hands, likely moonlighting from multiple major studios or between jobs at them. Later installments in the series exhibited strong resemblance to the styles of the abandoned MGM units that had produced “Captain and the Kids” cartoons (“Peg Leg Pedro”) and Walter Lantz (“The Princess and the Pauper”), the latter title also featuring some identifiable work of Jim Tyer between studio gigs. The short here being reviewed gives me the impression of heavy influence from the artists of the former Van Buren studio, benefitting immensely from their retooling in art training under the former direction of Burt Gilette and experience in Technicolor animation, who would have been looking for new work about this time. Many character designs, both of the humans and of the principal “star”, an elf who eventually became known as Nicky Nome, are similar enough in simple line design and rounded cheek features to suggest characters out of “Bold King Cole”, “A Waif’s Welcome”, and the like. But there are also other possible influences about, and some techniques which may be unique to this production. Possible MGM influence may be evidenced by a hound character, who is not too far distant from canines who appeared in MGM’s animation of the redesigned Bruno for the Bosko series, or from canines appearing in “The Pups’ Picnic” or “The Wayward Pups”, suggesting that some of Harman and Ising’s men may have moved on. A witch character is also somewhat MGM-like in design, though one special-effects technique (in a scene where she informs the audience that she even hates herself, demonstrated by delivering a lighting-force right cross to her own jaw) is one that does not appear to be recognizable as a signature effect of any other studio. And a group of cloudy evil spirits from the witch’s brew strongly suggest a cross between old man winter from “To Spring” and the spirits of ammonia from “Bottles”, also potentially giving away ex-MGM handiwork. One other design, of a well-animated female rabbit switchboard operator, is a mystery to place, as she seems a cross between the bunny designs from the girls’ school in Disney’s “The Tortoise and the Hare” and the rabbits in Fleischer’s “Bunny-Mooning”, leaving it anybody’s guess who created her.

The film is a direct sequel to the first episode of the series, A Coach for Cinderella. In the preceding cartoon (whose animation was respectable, but can’t hold a candle to the design and detail of this later film), Nicky Nome had filled in by taking on the responsibilities of a fairy godmother, who never appears or is spoken of in this version of the classic tale. Finding Cinderella weeping and alone, crying herself to sleep on the floor after her stepsisters have mistreated her and denied her the chance to go to the ball, Nicky takes measurements of her size from her sleeping form, then hurries atop his trusty steed, referred to as a “horsehopper” – a grasshopper body with a head more resembling a horse – into the woods, to round up a community of gnomes to do a good deed for Cinderella (in return for spoken-of kindnesses she has shown the gnomes in times before the cartoon). In mock-Disney style, forest animals and insects create a gown for Cindy, while the gnomes busy themselves constructing a pumpkin coach, which, at the end of the picture, they roll into a marvelous mechanical device called a “Modernizer”. As Cinderella is brought to the gnomes’ village, she marvels at the coach as it emerges out the other side of the Modernizer – now a 1930’s Chevy!

The film is a direct sequel to the first episode of the series, A Coach for Cinderella. In the preceding cartoon (whose animation was respectable, but can’t hold a candle to the design and detail of this later film), Nicky Nome had filled in by taking on the responsibilities of a fairy godmother, who never appears or is spoken of in this version of the classic tale. Finding Cinderella weeping and alone, crying herself to sleep on the floor after her stepsisters have mistreated her and denied her the chance to go to the ball, Nicky takes measurements of her size from her sleeping form, then hurries atop his trusty steed, referred to as a “horsehopper” – a grasshopper body with a head more resembling a horse – into the woods, to round up a community of gnomes to do a good deed for Cinderella (in return for spoken-of kindnesses she has shown the gnomes in times before the cartoon). In mock-Disney style, forest animals and insects create a gown for Cindy, while the gnomes busy themselves constructing a pumpkin coach, which, at the end of the picture, they roll into a marvelous mechanical device called a “Modernizer”. As Cinderella is brought to the gnomes’ village, she marvels at the coach as it emerges out the other side of the Modernizer – now a 1930’s Chevy!

The present Part 2 finds Nicky and the Chevy outside the palace gates, peering in at the festivities. (The other gnomes curiously make no appearance in this episode.) The party is getting started, and the medieval string trio seems to know how to swing it when they really get going. The prince makes his appearance, and passes up the stepsisters, to ask Cinderella to be his company for the evening. In a strange departure from the classic story’s continuity, and from the continuity of the previous cartoon as well, the stepsisters whisper to each other that if Cinderella is not home by midnight, she’ll lose her gown, coach, slippers – everything. Odd, as these provisos were never uttered by Nicky before, and would not seem inherent in gnome magic or lore. Odder still, how do the stepsisters know this, as they weren’t even present during any of the action where Nicky conducted his preceding handiwork? Anyway, with audience’s memories a bit fuzzy from whatever lapse of time there was between release of film #1 and film #2, the writers assume they can get away with this cheater exposition point. So, the stepsisters exit the ball, and seek out a remote cottage in the woods, which is the home of an old witch, whom they request accomplish the task of keeping Cindy from reaching her home base on time. In rhyming couplets, the witch concocts a cauldron brew, producing a transparent pair of dark spirits resembling in form a storm cloud with a walrus’s head, who pass over Nicky and the horsehopper outside. Nicky had spotted the stepsisters’ early departure from the ball, and followed them to the cottage. Nicky races to a flower, whose petals serve as the digits of a phone’s rotary dial, then speaks into the horn of another bloom to place a call to a forest wire service, where a written message is printed out on a scroll, with the use of the inked feet of a long-legged insect and a corn cob that serves as a typewriter barrel. The message s passed on to a bird, who carries it to Cinderella, advising her to get home by twelve or all is lost. Cindy deserts the prince, and races for her Chevy. The two spirits are tugging at the tires of the vehicle, trying to remove two of the wheels, but are unable to make them budge. Cindy virtually ignores them, climbing in the car from the passenger door, and hitting the accelerator, leaving the spirits in the dust. The prince and a hunting dog emerge from the castle, attempting to track Cinderella, but are unable to spot her, and further unable to attack the spirits, whose transparency allows the dog to leap right through them, and crash headfirst into a stone wall.

The present Part 2 finds Nicky and the Chevy outside the palace gates, peering in at the festivities. (The other gnomes curiously make no appearance in this episode.) The party is getting started, and the medieval string trio seems to know how to swing it when they really get going. The prince makes his appearance, and passes up the stepsisters, to ask Cinderella to be his company for the evening. In a strange departure from the classic story’s continuity, and from the continuity of the previous cartoon as well, the stepsisters whisper to each other that if Cinderella is not home by midnight, she’ll lose her gown, coach, slippers – everything. Odd, as these provisos were never uttered by Nicky before, and would not seem inherent in gnome magic or lore. Odder still, how do the stepsisters know this, as they weren’t even present during any of the action where Nicky conducted his preceding handiwork? Anyway, with audience’s memories a bit fuzzy from whatever lapse of time there was between release of film #1 and film #2, the writers assume they can get away with this cheater exposition point. So, the stepsisters exit the ball, and seek out a remote cottage in the woods, which is the home of an old witch, whom they request accomplish the task of keeping Cindy from reaching her home base on time. In rhyming couplets, the witch concocts a cauldron brew, producing a transparent pair of dark spirits resembling in form a storm cloud with a walrus’s head, who pass over Nicky and the horsehopper outside. Nicky had spotted the stepsisters’ early departure from the ball, and followed them to the cottage. Nicky races to a flower, whose petals serve as the digits of a phone’s rotary dial, then speaks into the horn of another bloom to place a call to a forest wire service, where a written message is printed out on a scroll, with the use of the inked feet of a long-legged insect and a corn cob that serves as a typewriter barrel. The message s passed on to a bird, who carries it to Cinderella, advising her to get home by twelve or all is lost. Cindy deserts the prince, and races for her Chevy. The two spirits are tugging at the tires of the vehicle, trying to remove two of the wheels, but are unable to make them budge. Cindy virtually ignores them, climbing in the car from the passenger door, and hitting the accelerator, leaving the spirits in the dust. The prince and a hunting dog emerge from the castle, attempting to track Cinderella, but are unable to spot her, and further unable to attack the spirits, whose transparency allows the dog to leap right through them, and crash headfirst into a stone wall.

Back at the cauldron, the witch materializes another, larger cloud monster, and instructs him not to fail her. The monster floats on ahead of the cast, down the road leading to Cindy’s and the stepsisters’ home, and knocks into the roadway every shrub, branch, and tree trunk it can fell. Cindy’s car approaches, and, in the falsest piece of advertising ever, is shown continuing down the road without so much as a deceleration, the “knee action” joints of the car’s wheel and spring assemblies allowing the tires to rise independently of one another and roll freely and cleanly over all the downed trunks and branches, barely vibrating the passenger cab! Meanwhile, the stepsisters have forgotten that they will need to travel the same road to get home, and follow in a traditional horse-drawn coach, getting thrown every which way inside the carriage every time they hit a bump. Seeing that her plan is getting nowhere, the old witch produces one more huge cloud, with traditional puffy face instead of walrus head, as the spirit of thunder, lightning, wind and rain. As a sign of his evil, before departing the cottage, the cloud knocks the witch into her own cauldron, we can only assume leading to her finish. The cloud then sets upon the task of striking the car with a thunderbolt, and pelting it with driving rain. Nicky offers no direct help this time, but he and the horsehopper pray to the god of all gnomes to see Cinderella safely through to her destination. He need not have wasted his prayer, as the car seems to be doing fine on its own, surviving the lightning blast without a scratch, and driving on through the rain-soaked road without so much as losing speed or getting plastered with mud. The stepsisters’ coach, however, finds its wheels half-submerged, slogging through the mud, while the coachman’s suit absorbs so much moisture, it shrinks to nearly nothing, exposing his bare pot belly. The storm cloud tries one more means of attack, when it spots an open pivoting glass window at the fore of the door to the passenger cab of the Chevy. Producing a tray full of ice cubes, the cloud inhales them, then produces a blowgun tube, through which he spits the cubes at Cindy like the firing of a machine gun. Chevy, however, was pushing these windows as aerodynamically “air-flow” designed, and the ice cubes are shown entering on one side of the window glass, then performing a turn to exit the car out the other side of the glass pane. The ice shoots back at the cloud monster, hitting him in the forehead, and causing him to cry – but the extra rain again does nothing to slow Cindy’s progress. On the other hand, the stepsisters’ coach finally cracks and splits in two, spilling the sisters out onto the road and into the mud. Cinderella arrives home, and the Chevy does not disappear.

Back at the cauldron, the witch materializes another, larger cloud monster, and instructs him not to fail her. The monster floats on ahead of the cast, down the road leading to Cindy’s and the stepsisters’ home, and knocks into the roadway every shrub, branch, and tree trunk it can fell. Cindy’s car approaches, and, in the falsest piece of advertising ever, is shown continuing down the road without so much as a deceleration, the “knee action” joints of the car’s wheel and spring assemblies allowing the tires to rise independently of one another and roll freely and cleanly over all the downed trunks and branches, barely vibrating the passenger cab! Meanwhile, the stepsisters have forgotten that they will need to travel the same road to get home, and follow in a traditional horse-drawn coach, getting thrown every which way inside the carriage every time they hit a bump. Seeing that her plan is getting nowhere, the old witch produces one more huge cloud, with traditional puffy face instead of walrus head, as the spirit of thunder, lightning, wind and rain. As a sign of his evil, before departing the cottage, the cloud knocks the witch into her own cauldron, we can only assume leading to her finish. The cloud then sets upon the task of striking the car with a thunderbolt, and pelting it with driving rain. Nicky offers no direct help this time, but he and the horsehopper pray to the god of all gnomes to see Cinderella safely through to her destination. He need not have wasted his prayer, as the car seems to be doing fine on its own, surviving the lightning blast without a scratch, and driving on through the rain-soaked road without so much as losing speed or getting plastered with mud. The stepsisters’ coach, however, finds its wheels half-submerged, slogging through the mud, while the coachman’s suit absorbs so much moisture, it shrinks to nearly nothing, exposing his bare pot belly. The storm cloud tries one more means of attack, when it spots an open pivoting glass window at the fore of the door to the passenger cab of the Chevy. Producing a tray full of ice cubes, the cloud inhales them, then produces a blowgun tube, through which he spits the cubes at Cindy like the firing of a machine gun. Chevy, however, was pushing these windows as aerodynamically “air-flow” designed, and the ice cubes are shown entering on one side of the window glass, then performing a turn to exit the car out the other side of the glass pane. The ice shoots back at the cloud monster, hitting him in the forehead, and causing him to cry – but the extra rain again does nothing to slow Cindy’s progress. On the other hand, the stepsisters’ coach finally cracks and splits in two, spilling the sisters out onto the road and into the mud. Cinderella arrives home, and the Chevy does not disappear.

The prince and his pooch finally arrive at Cindy’s home the next morning, the dog following the tire tracks right up to the tires themselves of the vehicle parked outside. The prince, carrying one of Cindy’s slippers, enters the home, places the footwear on his beloved, and asks to marry her. Cindy surprisingly states she cannot, as she has no dowry. The prince responds that what more dowry could he ask but Cindy herself – and her coach! The happy couple and the prince’s dog ride off in the Chevy, while Nicky and the horsehopper shake hands, riding on the rear trunk of the vehicle, for the fade out.

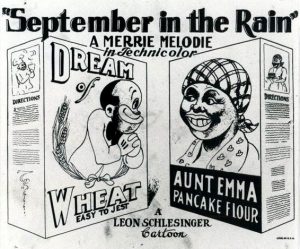

September in the Rain (Warner Merrie Melodies, 12/18/37 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Friz tries his hand at the same formula of a store coming to life at midnight, this time using the packages of various products at a grocery store. Unfortunately, Friz’s rendition does not have nearly the verve or timing of the Tashlin product, and, while smoothly executed in several scenes, is comparatively poky in pacing with the exception of an uptempo rendition of “Nagasaki” at the end, featuring caricatures of Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong, among others. It is another cartoon that sings more about the weather than depicting it, though a few shots leave room for raindrops. A still has surfaced of the original title card, depicting raindrops across it – indicating the titles were animated. The music cue is also evidently the title song, which is still playing when the original footage in the Blue Ribbon reissue kicks in. The Youtube channel of Ortitle Buddy Guddy has performed a remarkable recreation of these animated titles, even replete with a few “leaves of brown tumbling down” across the screen, in animation probably digitally lifted from “Now That Summer Is Gone”. The first shot of animation shows a routine rainstorm taking place outside the grocery store window, but most of the interior shots are dry as a bone. The film is partially a “cheater” with reused animation from several films of the past, including “Billboard Frolics” and “Flowers For Madame”. With product names slightly altered, an artificial “rain” is created as a waterfall on a box of shredded wheat pours down upon the umbrella girl from a Morton Salt cannister below (whose slogan was, and remains, “When it rains, it pours.”)

September in the Rain (Warner Merrie Melodies, 12/18/37 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Friz tries his hand at the same formula of a store coming to life at midnight, this time using the packages of various products at a grocery store. Unfortunately, Friz’s rendition does not have nearly the verve or timing of the Tashlin product, and, while smoothly executed in several scenes, is comparatively poky in pacing with the exception of an uptempo rendition of “Nagasaki” at the end, featuring caricatures of Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong, among others. It is another cartoon that sings more about the weather than depicting it, though a few shots leave room for raindrops. A still has surfaced of the original title card, depicting raindrops across it – indicating the titles were animated. The music cue is also evidently the title song, which is still playing when the original footage in the Blue Ribbon reissue kicks in. The Youtube channel of Ortitle Buddy Guddy has performed a remarkable recreation of these animated titles, even replete with a few “leaves of brown tumbling down” across the screen, in animation probably digitally lifted from “Now That Summer Is Gone”. The first shot of animation shows a routine rainstorm taking place outside the grocery store window, but most of the interior shots are dry as a bone. The film is partially a “cheater” with reused animation from several films of the past, including “Billboard Frolics” and “Flowers For Madame”. With product names slightly altered, an artificial “rain” is created as a waterfall on a box of shredded wheat pours down upon the umbrella girl from a Morton Salt cannister below (whose slogan was, and remains, “When it rains, it pours.”)

A raincoated boy from a Nabisco Uneeda Biscuit box joins the girl in a duet of “By a Waterfall.” A caricature of a blackfaced Al Jolson performs the title song, with one cutaway to a log cabin – a metal can of Log Cabin syrup, which in the days before plastic appeared in a signature can decorated to resemble a cabin. A rain is coming down upon the cabin, and the can develops windshield wipers upon the painted windows. That’s about it for storm action. A mystery remains about this film, as its reissue running time of under six minutes, and two tell-tale fade-outs and fade-ins, suggest that there are two cuts in the continuity. The fade transition had been similarly superimposed in reissue prints of Frank Tashlin’s “You’re an Education” and “Have You Got Any Castles?” to conceal edits, and transitions used in other parts of the surviving animation (consisting of only moving wipes) would suggest that the original film contained no fades to black. So what was in the missing scenes? The outrageousness of the blackface animation currently remaining would suggest that the reissue curs were not the result of censorship, as it is hard to imagine what sort of scenes could be more outrageous that the animation which is left. Warner, however, had exhibited two past uses of edits in other films for specific purposes – removal of celebrity caricatures when someone depicted had died before the cartoon’s reissue (for example, removal of Alexander Woolcott from “Have You Got Any Castles?”, and re-voicing of Elmer Fudd to remove verbal reference to Carole Lombard in “A Wild Hare”), and removal of references to countries which has become enemies of the nation during WWII. So who was the deceased celebrity who might have appeared in the missing scenes? (Woolcott again (who appeared in at least two cartoons for the studio)? Or someone else?) Or, what trademarks might have been excised to remove references to German, Italian, or Japanese foods? No internet source seems to provide speculation on this matter, so any input on this mystery will be appreciated.

A raincoated boy from a Nabisco Uneeda Biscuit box joins the girl in a duet of “By a Waterfall.” A caricature of a blackfaced Al Jolson performs the title song, with one cutaway to a log cabin – a metal can of Log Cabin syrup, which in the days before plastic appeared in a signature can decorated to resemble a cabin. A rain is coming down upon the cabin, and the can develops windshield wipers upon the painted windows. That’s about it for storm action. A mystery remains about this film, as its reissue running time of under six minutes, and two tell-tale fade-outs and fade-ins, suggest that there are two cuts in the continuity. The fade transition had been similarly superimposed in reissue prints of Frank Tashlin’s “You’re an Education” and “Have You Got Any Castles?” to conceal edits, and transitions used in other parts of the surviving animation (consisting of only moving wipes) would suggest that the original film contained no fades to black. So what was in the missing scenes? The outrageousness of the blackface animation currently remaining would suggest that the reissue curs were not the result of censorship, as it is hard to imagine what sort of scenes could be more outrageous that the animation which is left. Warner, however, had exhibited two past uses of edits in other films for specific purposes – removal of celebrity caricatures when someone depicted had died before the cartoon’s reissue (for example, removal of Alexander Woolcott from “Have You Got Any Castles?”, and re-voicing of Elmer Fudd to remove verbal reference to Carole Lombard in “A Wild Hare”), and removal of references to countries which has become enemies of the nation during WWII. So who was the deceased celebrity who might have appeared in the missing scenes? (Woolcott again (who appeared in at least two cartoons for the studio)? Or someone else?) Or, what trademarks might have been excised to remove references to German, Italian, or Japanese foods? No internet source seems to provide speculation on this matter, so any input on this mystery will be appreciated.

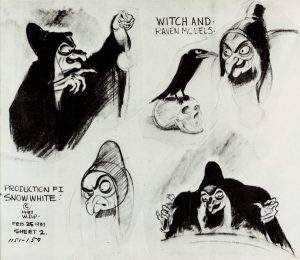

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Disney/RKO, 12/21/37) – For the second time in the season, Disney would prove that a storm could serve as the heightening impetus for drama. Two spots in this classic include incredibly realistic weather action. As a final step toward concocting the brew to transform the wicked queen into the disguise of an old hag, she holds the goblet to the window of the castle, gathering the force of “a blast of wind, to fan my hate”, and then, “a thunderbolt, to mix it well.” These touches superbly reinforce that something evil and sinister is about to happen, and Disney does not fail to deliver, in one of the most memorably frightening sequences ever presented on the animated screen, as the potion is swallowed, the room begins to spin, and the queen nearly collapses from the impact of transformation that whitens her hair, reduces her hands to bony claws, and alters her velvet-toned voice into a fearsome cackle. The climactic point in the classic tale finds the queen-turned-hag triumphant in the dwarfs’ cottage, at having deceived Snow White into biting into the poisoned apple. But the animals of the forest have witnessed her treachery, and race off to the diamond mine to spread the alarm to the seven dwarfs. Grumpy, despite his previous protests against females a “pizen” and “full of wicked wiles”, shows his true feelings for Snow White by leading the charge atop the back of a deer, as the dwarfs form a rescue party to attempt to foil the queen. They arrive just in time to see the hag leaving the cottage, and charge after her, just as lightning flashes though the sky, and a steady downpour of rain blankets the forest, again adding to the dramatic impact. The tension builds as does the storm, as the pursuit leads the queen into entanglements of vines, and up the steep slope of a tall rocky peak, while the dwarfs maintain a hot pursuit, scrambling up the rain-soaked rocks with clubs in hand, as a determined, unstoppable army.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Disney/RKO, 12/21/37) – For the second time in the season, Disney would prove that a storm could serve as the heightening impetus for drama. Two spots in this classic include incredibly realistic weather action. As a final step toward concocting the brew to transform the wicked queen into the disguise of an old hag, she holds the goblet to the window of the castle, gathering the force of “a blast of wind, to fan my hate”, and then, “a thunderbolt, to mix it well.” These touches superbly reinforce that something evil and sinister is about to happen, and Disney does not fail to deliver, in one of the most memorably frightening sequences ever presented on the animated screen, as the potion is swallowed, the room begins to spin, and the queen nearly collapses from the impact of transformation that whitens her hair, reduces her hands to bony claws, and alters her velvet-toned voice into a fearsome cackle. The climactic point in the classic tale finds the queen-turned-hag triumphant in the dwarfs’ cottage, at having deceived Snow White into biting into the poisoned apple. But the animals of the forest have witnessed her treachery, and race off to the diamond mine to spread the alarm to the seven dwarfs. Grumpy, despite his previous protests against females a “pizen” and “full of wicked wiles”, shows his true feelings for Snow White by leading the charge atop the back of a deer, as the dwarfs form a rescue party to attempt to foil the queen. They arrive just in time to see the hag leaving the cottage, and charge after her, just as lightning flashes though the sky, and a steady downpour of rain blankets the forest, again adding to the dramatic impact. The tension builds as does the storm, as the pursuit leads the queen into entanglements of vines, and up the steep slope of a tall rocky peak, while the dwarfs maintain a hot pursuit, scrambling up the rain-soaked rocks with clubs in hand, as a determined, unstoppable army.