Note: There’ll be a pop quiz at the end of next week’s article. How many of the classic animated stars of the theatrical cartoon shorts “tied the knot” in actual (not dreamed) wedlock at some point in their career? Think about it. (No fair posting any answers until next week – our moderator will edit or delete any advance answers submitted this week; we want everyone to get a chance to test their memories.)

Today, we begin a two-part exploration of two different trails, with seemingly converging origins, and reconverging again at various times.

Marriage (and its consequences) have long been targets of comedy – probably since the days of Adam and Eve. It was certainly a staple of the early silent cinema (Keystone Comedies, Laurel & Hardy, Charley Chase, etc.), and undoubtedly of vaudeville before that. Even Shakespeare (lest we forget “The Taming of the Shrew”). So it was of course no surprise that such fare would rub off on the animation industry. But animation could take such themes in directions no live action comedy could afford. Particularly when casts of astronomical proportions were needed to depict prodigious offspring. Especially when they all needed to bear startling resemblance to the star of the piece. And animation seemed to also, more believably than live-action comedy, provide an escape-hatch for such situations – the inevitable awakening from a nightma…that is, dream.

Marriage (and its consequences) have long been targets of comedy – probably since the days of Adam and Eve. It was certainly a staple of the early silent cinema (Keystone Comedies, Laurel & Hardy, Charley Chase, etc.), and undoubtedly of vaudeville before that. Even Shakespeare (lest we forget “The Taming of the Shrew”). So it was of course no surprise that such fare would rub off on the animation industry. But animation could take such themes in directions no live action comedy could afford. Particularly when casts of astronomical proportions were needed to depict prodigious offspring. Especially when they all needed to bear startling resemblance to the star of the piece. And animation seemed to also, more believably than live-action comedy, provide an escape-hatch for such situations – the inevitable awakening from a nightma…that is, dream.

Animation could also take its own slant on the origin of so many marital problems – a certain feathered creature that was the traditional answer to the question “Where do babies come from?” (Unless you choose to follow the school of UPA’s strange 1955 aberration, Baby Boogie.) The “Winged Scourge” of Mr. Stork became a dependable cartoon staple to bring glee to the eyes of a woman – and daggers to the eyes of a man.

While marital comedies frequently took the form of henpecked husbands bullied by the proverbial battle-axe of a spouse armed with a rolling pin (as in early series such as the Katzenjammer Kids and Mutt and Jeff (see, for example, Domestic Difficulties (1916)), and even Felix the Cat and Krazy Kat had their share of spouse trouble (for example, Felix Woos Whoopee (1928), and Krazy’s Sleepy Holler (1929)), our focus for marital mayhem shall be more upon the cautionary tales of multiplicitous reproduction, unions of convenience, or dreams of wedded bliss gone awry – often with our hero or heroine narrowly escaping that inescapable fate. In these departments, animation excelled, achieving through broad brushstrokes of imagination more lasting images to send chills to those facing the altar than any live action film perhaps ever mustered.

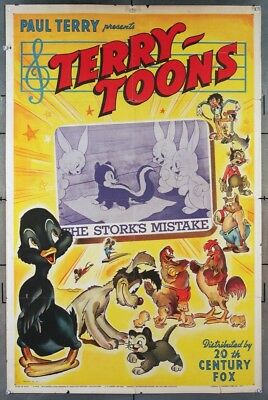

Titles alone from the filmographies of early silent series offer little guidance to locating early warnings about wedlock. However, the output of Paul Terry’s Aesops Fables studio reveals at least one intriguing tidbit of information as to possible origins of the stork legend in animation – a 1923 listing titled, The Stork’s Mistake. Intriguing particularly in that the identical title was used by Terry for a subsequent sound cartoon released by Fox on 5/29/42. A remake? Knowing Terry’s reputation for retreading gags and animated sequences, it’s a possibility. The silent doesn’t appear to be available (information from anyone with trade publications would be most helpful), so, on the leap of faith that the ‘42 version gives us some insight, we’ll review it here out of sequence.

Titles alone from the filmographies of early silent series offer little guidance to locating early warnings about wedlock. However, the output of Paul Terry’s Aesops Fables studio reveals at least one intriguing tidbit of information as to possible origins of the stork legend in animation – a 1923 listing titled, The Stork’s Mistake. Intriguing particularly in that the identical title was used by Terry for a subsequent sound cartoon released by Fox on 5/29/42. A remake? Knowing Terry’s reputation for retreading gags and animated sequences, it’s a possibility. The silent doesn’t appear to be available (information from anyone with trade publications would be most helpful), so, on the leap of faith that the ‘42 version gives us some insight, we’ll review it here out of sequence.

A stork is seen flying overhead with a bundle in its mouth. A hen and her brood of two unhatched eggs run for cover into their coop, and raise a “Detour” sign out of the roof, causing the stork to turn elsewhere. Others of the community race to their rooftops and demolish all chimneys. Only papa rabbit (already with a sizeable family) is caught too late. Though he barricades himself and his offspring inside the house, the stork drops a bundle down the stovepipe. Inexplicably, it’s a mistaken delivery of a baby skunk! The rest is standards Terry fare (obviously updated for sound from the possible original, in the use of a Baby Snooks impersonation between skunk and papa (see column on this website re Fanny Brice in the “Radio Roundup” series)) as the skunk is thrown out but proves himself by saving the family from a trio of hunting hounds. Nevertheless, if this parallels the original, a first foundation has been laid for a subgenre of titles to follow involving mistaken deliveries, as will be seen below.

A notable aside is that there is the remote possibility that live action comedy may have inspired Terry to create this title in the first place. The identical title, The Stork’s Mistake, was used in 1921 for a live-action comedy starring a Baby John Henry, Doreen Turner, and Coy Wilson. No synopsis appears available. While it may be unlikely that an actual stork was depicted in such comedy, it was not unheard of. A real stork, augmented by some puppet animation inserts, appears in a Columbia musical short, Um-Pa, in 1934. We can probably safely surmise, however, that no skunk was involved in the 1921 effort. Still, the film might have given Paul some ideas.

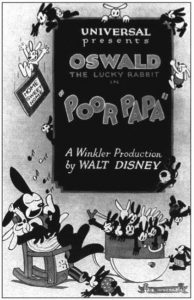

While again the often lost or at least unavailable history of silent animation may not be thoroughly mined for other links for this trail, a reasonable starting point among that which would follow roots from the pens of the fledgling Disney studio. Poor Papa (1927, released 6/11/28), the first produced Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon, is highly prototypical of what was to come. One difference, however, between this early effort and several future re-treatments is that Oswald is really living in a nightmare environment, rather than experiencing it only in a flight of fancy. Rabbits, after all, have a certain reputation for large families. Expectant father Oswald paces the floor outside the bedroom, while on the roof, a flock of storks pours sacks and sacks of kids down the stove-pipe, using a funnel to ensure they hit their target. A doctor comes out of the bedroom, offering Ozzie a congratulatory handshake, then informing him of the number of new arrivals by repeated counts by fives on his fingers – when he gets past fifteen, Oswald holds up a traffic sign reading “STOP”. Glancing in the bedroom, we see mama in the center of a bed wide enough to hold a new wing of little ones on either side. Oswald is knocked rather dizzy. However, we next see him adopting his share of the family chores – by use of conveyor belts to drag the kids through a washing machine wringer and then hang them by their ears on a clothesline to dry.

While again the often lost or at least unavailable history of silent animation may not be thoroughly mined for other links for this trail, a reasonable starting point among that which would follow roots from the pens of the fledgling Disney studio. Poor Papa (1927, released 6/11/28), the first produced Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon, is highly prototypical of what was to come. One difference, however, between this early effort and several future re-treatments is that Oswald is really living in a nightmare environment, rather than experiencing it only in a flight of fancy. Rabbits, after all, have a certain reputation for large families. Expectant father Oswald paces the floor outside the bedroom, while on the roof, a flock of storks pours sacks and sacks of kids down the stove-pipe, using a funnel to ensure they hit their target. A doctor comes out of the bedroom, offering Ozzie a congratulatory handshake, then informing him of the number of new arrivals by repeated counts by fives on his fingers – when he gets past fifteen, Oswald holds up a traffic sign reading “STOP”. Glancing in the bedroom, we see mama in the center of a bed wide enough to hold a new wing of little ones on either side. Oswald is knocked rather dizzy. However, we next see him adopting his share of the family chores – by use of conveyor belts to drag the kids through a washing machine wringer and then hang them by their ears on a clothesline to dry.

More of the kids wreak havoc on both real and personal property, including dancing on the piano, and applying saws, drills, and axes to the furniture. Oswald’s attempts to conduct other household chores such as churning butter are so often interrupted by the tykes that he has to take a fly swatter to ward them off. After a few more mishaps, Oswald decides enough is enough. He climbs up on the roof carrying a shotgun. Pulling out a telescope from his pocket, he spots what he most fears – another aerial armada of storks flying in his direction. Ozzie posts a sign on the rooftop stovepipe reading “No Vacancies.” He then takes aim and commences firing. The first stork gets a bundle through to the stovepipe, but the others are temporarily deterred by Oswald’s gun blasts. One stork gets hit in the tail feathers and drops his bundle – but the kids make it into the stovepipe anyway by using the bundle fabric as a parachute. Determined, Oswald physically ties a knot in the stovepipe, seemingly leaving no point of entry for further deliveries. But the storks are equally determined. They re-route their deliveries to a nearby water tower, with pipe connected to Oswald’s home. Believing himself victorious, Oswald laughs uproariously inside the house, and turns on the tap to refresh himself with a drink of water – but gets a non-stop flow of new kids instead. Ozzie collapses in a dead faint, and we iris out.

In its time, this early effort, despite a solid story premise told well in typical Disney fashion, was probably not very influential. Universal was dissatisfied with the first model for its new character, and demanded a reworking to give Oswald more rounded features and youthful appearance. And they almost didn’t give this cartoon a chance. It was held back in the production line, in favor of Ozzie’s redesigned debut in Trolley Troubles. And still they continued to hold it back for release – well into the next season. It’s possible Universal did not heavily promote the film, but only squeaked it in to meet production quota – almost sweeping it under the rug.

In its time, this early effort, despite a solid story premise told well in typical Disney fashion, was probably not very influential. Universal was dissatisfied with the first model for its new character, and demanded a reworking to give Oswald more rounded features and youthful appearance. And they almost didn’t give this cartoon a chance. It was held back in the production line, in favor of Ozzie’s redesigned debut in Trolley Troubles. And still they continued to hold it back for release – well into the next season. It’s possible Universal did not heavily promote the film, but only squeaked it in to meet production quota – almost sweeping it under the rug.

Possibly the only studio initially influenced to a degree by the Oswald effort was Charles Mintz, first for a silent at Paramount, and not so long thereafter, for a talkie at Columbia. Under the helm of Ben Harrison and Manny Gould, Krazy Kat would have two unexpected visits within a mere few years to the realm of old doc stork, in The Stork Exchange (12/10/27), and The Stork Market (7/20/31) (the latter essentially a sound remake of the first). These may mark animation’s first visit to the stork’s own domain. Similar to Oswald, both films present a large number of babies and assembly-line techniques in their production. However, as it is obvious the babies are not all from the same parentage, these are not truly marital cartoons, but form a second genre without particular cautionary messages to prospective newlyweds. Both titles also share a potential common thread with the Paul Terry above – in both, Krazy winds up misdelivered instead of the real baby.

The latter title embellishes a bit on the assembly line, with one stork stamping approvals on the diapers of several kids – one printed in Chinese for a stereotype baby of such origin, and an obvious Jewish stereotype baby stamped with the Hebrew letters for “Kosher for Passover”. This latter gag and the assembly line form a direct link of material to a 1933 Harman-Ising cartoon, discussed below.

The coincidence of multiple babies on an assembly line occurring in two studios in the same year of 1927 raises some speculation – did Mintz just independently stumble on a similar theme (considering that the Oswald wasn’t officially released until 1928)? Or had Disney “shopped around” his Oswald pilot for distribution, so that the Mintz boys got wind of at least some of its ideas in advance of release and played “kopy kat”? As lighting rarely gets captured in a bottle twice, I’m inclined to believe the second theory. Still, the Mintz products deserve note for creating a new focus from the stork’s point of view rather than the parents.

It is unknown what the message was for the unavailable Max Fleischer Talkartoon, Marriage Wows (1929). No synopsis has appeared on internet sources – not even in vintage trades on early talkie shorts available online, and the only elements are still in the vaults at UCLA Film Archive. (Why doesn’t anybody sponsor a restoration of this film so at least one projectable print can be seen?) Anyone know of any reviews from way back when?

Birth of Jazz (Columbia/Mintz, Krazy Kat, 4/13/32 – Manny Gould, dir.), features a brief, but one of the most flamboyant, entrances for the winged delivery service. Three storks riding upon motorcycles as a police escort skim along the clouds, with three more storks hidden in the horns of their scooters to protrude their heads at intervals and blow a trumpet fanfare. The actual delivery stork brings up the rear (carrying Krazy as the spirit if jazz), but makes his delivery more awkwardly than expected, as his rear end is struck by lightining and he drops the bundle through the clouds.

Spring Is Here (Educational Pictures/Terrytoon, 7/24/32), a plotless assemblage of random gags on the season, offers us a brief glimpse of the stork making a delivery to the small house of Mr. and Mrs. Duck – which he does by pulling out a carton of eggs and depositing the first half of it one by one down a small chimney, then unceremoniously pouring in the rest. That’s all they wrote.

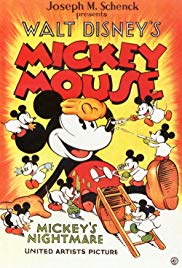

If anyone recognized the influential value of Poor Papa, it was Disney himself. By 1932, he was out of the clutches of Carl Laemmle, and riding on the crest of the wave of popularity for his mega-star Mickey Mouse. Oswald may have been a regrettable reminder not to fall prey to the studio system again, but there was plenty to distract Disney away from such distant memories. Nevertheless, a certain fondness must have lingered for his original pilot, which perhaps Disney felt had been given the bum’s rush by Laemmle. With the aid of his new star, advanced animation techniques, and a much more skilled artist staff, Disney decided that the old idea could be dressed up to be bigger and better than ever. Something to set the industry on its ear. Pulling out all the stops, a new title entered production, to be scheduled as Mickey’s season opener for his new distribution contract with United Artists for the 1932-33 season: Mickey’s Nightmare (8/13/32, David Hand, dir.).

Everything was new and improved. Instead of the bare-background shot of Mickey and Minnie with a grade-school chalkboard to announce the title, Mickey and Minnie were placed in the spotlight of a curtained theater stage. Preceding their joint appearance was the startling entrance (set to the sound of a drum roll and an ascending slide whistle) of a large ethereal floating head of Mickey coming closer and closer to the camera, amidst a circling aura of animated sunbeams – then literally exploding right in our face, revealing out of the blast the theater shot. The first time I ever saw this opening (saved on at least one of the titles on Disney Treasures’ “Mickey Mouse in Black and White” DVD box, though the UA credit on the print had been doctored), I nearly keeled over from the shock. Imagine what theatergoers must have felt. A new end title with the mice still on the theater stage was also added. (From the notable research of David Gerstein in his article, “Mouse Interrupted”, this appears to be the only UA title to feature a Bray-Hurd Patent reference on the end card below the stage, which has been restored via stills from David’s work on several fine reconstructions online.)

Everything was new and improved. Instead of the bare-background shot of Mickey and Minnie with a grade-school chalkboard to announce the title, Mickey and Minnie were placed in the spotlight of a curtained theater stage. Preceding their joint appearance was the startling entrance (set to the sound of a drum roll and an ascending slide whistle) of a large ethereal floating head of Mickey coming closer and closer to the camera, amidst a circling aura of animated sunbeams – then literally exploding right in our face, revealing out of the blast the theater shot. The first time I ever saw this opening (saved on at least one of the titles on Disney Treasures’ “Mickey Mouse in Black and White” DVD box, though the UA credit on the print had been doctored), I nearly keeled over from the shock. Imagine what theatergoers must have felt. A new end title with the mice still on the theater stage was also added. (From the notable research of David Gerstein in his article, “Mouse Interrupted”, this appears to be the only UA title to feature a Bray-Hurd Patent reference on the end card below the stage, which has been restored via stills from David’s work on several fine reconstructions online.)

The feelings of lavishness don’t quit there. Our scene opens to an evening shot, bathed in the lights and shadows of a nightstand candle, of Mickey’s bedroom, as he and Pluto whisper their evening prayers before bedding down for the night. Pluto wants to share Mickey’s comfortable mattress, but Mickey chases him out, sending him to his own doggie bed in the corner. Sighing at a picture of Minnie on one end-table, Mickey takes a statue of Dan Cupid from the other end table, and places it with its arrow pointed at Minnie’s heart. He puts out the candle with one blow of a mallet, changing the room lighting entirely into heavy shadow. (Thatta boy, Walt. Show up all those upstart rivals with your special effects.) He nods off to sleep, but Pluto crawls back in bed and joins him. Pluto affectionately licks Mickey’s face, which Mickey, in a thought cloud appearing over his head, misinterprets as the kiss of Minnie. In his dream, Minnie gives him a few more kisses, then reveals to the audience the reason for her happiness – she is wearing a large engagement ring.

The shot dissolves to an array of pealing wedding bells, then to chapel interior, where Minnie in wedding veil and a jittery Mickey appear before the preacher. As the crucial question is asked of Mickey, Mickey in disoriented fashion stammers in reply, “Y-y-y-y-Yes, M’aam’, to Minnie’s giggles. Shortly, Mickey is seen standing outside a honeymoon cottage, whistling happily and hosing down the lawn with Pluto. His attention is drawn to the skies above, as a stork appears in the sky and drops a bundle down the chimney. Pluto is the first to congratulate Mickey, offering him a paw in handshake while Mickey smiles in slightly embarrassed and humble fashion. But peace is not to remain long. In direct parallel to “Poor Papa”, we see again a much fancier-than-the-original mass delivery of more – and more – and more babies down the chimney, the last one pouring them in by a bucket (in similar fashion to the Oswald funnel).. Mickey is aghast, but Pluto again attempts to offer Mickey his paw in congratulations, only to have Mickey disgustedly reject the offer with a slap to his paw. Mickey races inside, and in another direct remake of the Oswald shot, Minnie is seen in a room-wide bed with dozens of little Mickeys (the origins of who would come to be known as the “orphans” in numerous subsequent episodes – did Mickey ultimately put them up for adoption?) The remainder of the cartoon follows in similar fashion to the first half of “Poor Papa” – the destructive consequences to Mickey’s household of being overrun by children. Piano is again pounded upon, this time by a quartet of mice in multi-hands arrangement.

The shot dissolves to an array of pealing wedding bells, then to chapel interior, where Minnie in wedding veil and a jittery Mickey appear before the preacher. As the crucial question is asked of Mickey, Mickey in disoriented fashion stammers in reply, “Y-y-y-y-Yes, M’aam’, to Minnie’s giggles. Shortly, Mickey is seen standing outside a honeymoon cottage, whistling happily and hosing down the lawn with Pluto. His attention is drawn to the skies above, as a stork appears in the sky and drops a bundle down the chimney. Pluto is the first to congratulate Mickey, offering him a paw in handshake while Mickey smiles in slightly embarrassed and humble fashion. But peace is not to remain long. In direct parallel to “Poor Papa”, we see again a much fancier-than-the-original mass delivery of more – and more – and more babies down the chimney, the last one pouring them in by a bucket (in similar fashion to the Oswald funnel).. Mickey is aghast, but Pluto again attempts to offer Mickey his paw in congratulations, only to have Mickey disgustedly reject the offer with a slap to his paw. Mickey races inside, and in another direct remake of the Oswald shot, Minnie is seen in a room-wide bed with dozens of little Mickeys (the origins of who would come to be known as the “orphans” in numerous subsequent episodes – did Mickey ultimately put them up for adoption?) The remainder of the cartoon follows in similar fashion to the first half of “Poor Papa” – the destructive consequences to Mickey’s household of being overrun by children. Piano is again pounded upon, this time by a quartet of mice in multi-hands arrangement.

A pillow fight with Mickey is interrupted when one of the mice hits him with a “loaded glove” – a pillowcase, inside which Mickey finds the cracked remains of what before the blow was the chamber pot. A paint supply is raided from a workshop pantry, leading to Pluto being painted with tiger stripes, a carpet sweeper reconverted to a paint applicator, and an often-censored scene where a white marble bust is converted to blackface by a spritz of paint from a seltzer bottle. Finally, Mickey is rear-ended by a plunger, driven through the pull cords of some draperies covering a doorway, and tied up in the cords like a hostage on the floor as the mice continue to assault him with the carpet sweeper/paint applicator, a ringing telephone in one ear, and a cuckoo clock in the other ear. The scene dissolves, to find Mickey back in his bed with Pluto, now morning, with the curtain cords replaced by Mickey’s bedsheets knotted around him, the telephone actually being his ringing alarm clock, the cuckoo bird replaced by a crowing rooster perched on the sill of his open window, and the paint applicator replaced by Pluto’s loving morning-kiss slurps. Realizing it was all a dream, Mickey grabs the mallet he used earlier and brings it down soundly on the statue of Dan Cupid, destroying it. He shouts, “Whoopee!!”, tosses his pillow in the air, and he and Pluto dance with joy amidst a shower of pillow feathers, as we iris out. Unlike Oswald, this cartoon would have widespread influence, as we will later see.

Wedding Bells (Columbia/Charles Mintz, Krazy Kat, 1/10/33 – story: Ben Harrison) stands as one of the few animated marriage films in which everything is positive in mood! A fairly straight telling of a cartoon couple’s wedding ceremony, with no cautions. At least when Oswald the Rabbit came up with a similar finale to Five and Dime (Universal/Lantz, 9/18/33), Tex Avery was there to be sure that when the couple reached their honeymoon cottage, Doc Stork was already waiting on the rooftop, at the ready to make his delivery by and by. Both titles fall somewhat off our beaten trail.

Wedding Bells (Columbia/Charles Mintz, Krazy Kat, 1/10/33 – story: Ben Harrison) stands as one of the few animated marriage films in which everything is positive in mood! A fairly straight telling of a cartoon couple’s wedding ceremony, with no cautions. At least when Oswald the Rabbit came up with a similar finale to Five and Dime (Universal/Lantz, 9/18/33), Tex Avery was there to be sure that when the couple reached their honeymoon cottage, Doc Stork was already waiting on the rooftop, at the ready to make his delivery by and by. Both titles fall somewhat off our beaten trail.

Meanwhile, Shuffle Off To Buffalo (Warner, Merrie Melodies (B&W), Hugh Harman/Rudolf Ising, 7/8/33 – “Drawn by” Isadore (Friz) Freleng and Paul Smith) was remembering and paying “homage” to the Krazy Kat stork factory episodes of a few seasons earlier – with far greater elaboration. In a musicale set to Warner’s recent song hit from “42nd Street” (3/11/33 ), a father time-type chief presides over stork headquarters. He processes an order for twins from Nanook of the North by pulling two Eskimo babies out of an icebox and placing them in a double bundle in a waiting stork’s mouth – one bundle marked “upper berth”, the other “lower berth”. A request for a baby written in Hebrew is sent to the stockroom and filled with a Jewish stereotype baby, who sings “Oy Yoy!”, and he again has his diaper stamped with symbols for “Kosher for Passover”. Later scenes include both Chinese and two black babies (billed as the “Gold Dust Twins” – reference to a washing powder of the day using similar stereotypes on its label). Additional celebrity impersonations appear among both babies and “house elves” who tend to them, including views of Maurice Chevalier, Joe E. Brown, Eddie Cantor, and Ed Wynn. But the most elaborate sequence involves a massive conveyor belt system, first delivering the babies from a production room, dousing them in a washing machine, drying them with a restroom roller towel, powdering them through a sieve, flipping them to land in triangular diapers from a paper towel dispenser, and the diapers fastened on with a stapler. (Of course, one baby has an “accident” just after being finished, and is without ceremony carried back to the washing machine and dumped in to begin the process all over again.) This production line would be remembered shortly after for an early 2 strip Technicolor effort by Freleng, and by Bob Clampett in a berserk masterpiece in the 1940’s.

The Pied Piper (Disney/UA, Silly Symphony, 9/16/33, Wilfred Jackson, dir.) – A brief cameo. As the piper pipes the children away from Hamelin, the stork circles over a rooftop, about to make a delivery. Realizing that all the children are leaving, he instead flies after the piper.

Honeymoon Hotel (Warner, Merrie Melodies (2 strip Cinecolor), 2/17/34 – Earl Duvall, dir.) is another rare pro-marriage cartoon. Based on the equally outrageous Busby Berkeley-directed “prologue” (a live musical revue played between pictures in prestigious movie houses) featured in Footlight Parade (1934), one of the few musicals allowing James Cagney to shine, this entertaining and well-paletted cartoon is generally euphoric in mood, following the wedding and wedding night of a ladybug and tumblebug. About the only cautionary message one can read into this cartoon is that when you’re in love, the whole world is watching! Including the house detective, the hotel staff (at keyholes, transoms, and even by periscope), and even the moon itself (causing the lovers to shut out the lights, leaving the moon to demonstrate the two-strip color range as he changes color to match his dialog line, “Is my face red!”) Notably, the moon gag has just this year been elaborated into one of Disney Channel’s new Mickey Mouse episodes, entitled, “Over the Moon”. Only a fire which burns down the remainder of the hotel (apparently sparked by the heat intensity of the lovers’ kiss) leaves the couple, as Greta Garbo would say, “alone”. This being pre-code, they disappear into a Murphy bed together which folds into the wall, revealing a calendar hung on the wall which rises up beneath the bed, depicting a baby-bonneted infant bug, who winks at the camera as we fade out. Never generally included in the A.A.P. Merrie Melodies package to television – either the negatives weren’t available, or A.A.P. may have thought it too racy for the kiddies.

Honeymoon Hotel (Warner, Merrie Melodies (2 strip Cinecolor), 2/17/34 – Earl Duvall, dir.) is another rare pro-marriage cartoon. Based on the equally outrageous Busby Berkeley-directed “prologue” (a live musical revue played between pictures in prestigious movie houses) featured in Footlight Parade (1934), one of the few musicals allowing James Cagney to shine, this entertaining and well-paletted cartoon is generally euphoric in mood, following the wedding and wedding night of a ladybug and tumblebug. About the only cautionary message one can read into this cartoon is that when you’re in love, the whole world is watching! Including the house detective, the hotel staff (at keyholes, transoms, and even by periscope), and even the moon itself (causing the lovers to shut out the lights, leaving the moon to demonstrate the two-strip color range as he changes color to match his dialog line, “Is my face red!”) Notably, the moon gag has just this year been elaborated into one of Disney Channel’s new Mickey Mouse episodes, entitled, “Over the Moon”. Only a fire which burns down the remainder of the hotel (apparently sparked by the heat intensity of the lovers’ kiss) leaves the couple, as Greta Garbo would say, “alone”. This being pre-code, they disappear into a Murphy bed together which folds into the wall, revealing a calendar hung on the wall which rises up beneath the bed, depicting a baby-bonneted infant bug, who winks at the camera as we fade out. Never generally included in the A.A.P. Merrie Melodies package to television – either the negatives weren’t available, or A.A.P. may have thought it too racy for the kiddies.

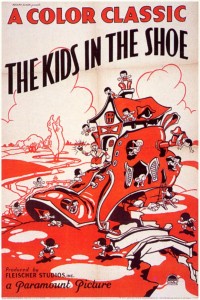

The Kids In the Shoe (Paramount, Fleischer Color Classic (2-strip) – 5/19/35, Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Knietel, Roland Crandall, Animation) – One of the top entries in the Color Classics series, perhaps staying the closest of any of them to the trademark Fleischer house style, as opposed to the “Disneyfied” influence of other episodes. The trials and tribulations of the old woman – fairyland’s poster girl for overpopulation – are vividly depicted. Kids by the dozens cavort on every facet of the shoe, including using the shoestrings as both ladders and slides. The women faces the inevitable daily task of rounding up the kids for dinner and bed. At the dinner table, the kids avoid eating their “broth and bread” by dumping spoonful after spoonful on the floor – but the old woman spots the family cat lapping it up below the table, and sends the kids off to bed without further food. In a series of gags reused years later in “Me Musical Nephews” (1942) for Popeye’s nephews, the kids, at respective sinks and medicine cabinets, avoid tooth brushing by putting toothpaste on the reflection of their teeth in the mirror and brushing the mirror instead of their own teeth. Washing consists of filling a basin, then dabbing only two drops of water on each cheek with a single finger. Eventually, the kids make it to bed, with their cradles linked by a pair of ropes to the old woman’s rocking chair so they are rocked as she rocks.

The Kids In the Shoe (Paramount, Fleischer Color Classic (2-strip) – 5/19/35, Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Knietel, Roland Crandall, Animation) – One of the top entries in the Color Classics series, perhaps staying the closest of any of them to the trademark Fleischer house style, as opposed to the “Disneyfied” influence of other episodes. The trials and tribulations of the old woman – fairyland’s poster girl for overpopulation – are vividly depicted. Kids by the dozens cavort on every facet of the shoe, including using the shoestrings as both ladders and slides. The women faces the inevitable daily task of rounding up the kids for dinner and bed. At the dinner table, the kids avoid eating their “broth and bread” by dumping spoonful after spoonful on the floor – but the old woman spots the family cat lapping it up below the table, and sends the kids off to bed without further food. In a series of gags reused years later in “Me Musical Nephews” (1942) for Popeye’s nephews, the kids, at respective sinks and medicine cabinets, avoid tooth brushing by putting toothpaste on the reflection of their teeth in the mirror and brushing the mirror instead of their own teeth. Washing consists of filling a basin, then dabbing only two drops of water on each cheek with a single finger. Eventually, the kids make it to bed, with their cradles linked by a pair of ropes to the old woman’s rocking chair so they are rocked as she rocks.

But, as the old woman heads upstairs to the master bedroom, believing the kids have settled down for the night, one of the kids produces a guitar from under the bedsheets, another a trumpet, another a “jew’s harp”, and a fourth mans an upright piano – and they break into a raucous country rendition of “Mama Don’t Allow It” (see background on the recording used as underscore in James Parten article “Max Fleischer and Novelty Records” on Needle Drop Notes subchannel, this site), which develops into a pillow fight and the destruction of most of the mattresses. (This musical carousing would also become the central plot point of Me Musical Nephews and its later Technicolor remake, Riot in Rhythm (1950).) The whole shoe starts rocking to the beat, and physically dances several blocks down the street. The old woman is finally aroused, and when the kids won’t stop, she resorts to her secret weapon – a large jug labeled “Castor Oil”. Armed with this and a giant tablespoon, she approaches the kids. The sight is enough to bring terror to any toddler’s eyes, and they all obediently resort to complete quiet and disappear under the bedcovers. When they are all securely in bed where they can’t see, the old woman breaks the fourth wall and shows us that the jug label is a fake, peeling it back to reveal the words, “Sweet Cider”. Her curtain line: “So you see that raising children isn’t very hard to do, if you only take it easy like the woman in the shoe!”, and we iris out while she takes a healthy swig from the jug.

For Better or Worser (Paramount/Fleischer, Popeye, 6/28/35 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.) – The first of a string of Popeye cautionary tales, entirely original, and one of the first to remind caution at considering marriage for the wrong reasons. Popeye is seen in his bachelor apartment, wearing an apron, attempting to make dinner. His cooking skills definitely don’t match his fighting skills – items burn, boil over, and fill the room with smoke. Disgusted, Popeye throws down the apron, and announces, “It’s no use! I have t’ get me a wife.” He walks down the street to a local matrimonial agency (accompanied by the musical cue, “Love is Just Around the Corner”). Coincidently, Bluto has reached the same idea, and is already inside. Photos of available spouses appear on a wall – and of course our two romantically-blind sailors both choose the ugliest one of all – Olive, whose back is turned in the photo. A buzzer is rung by an attendant to an adjoining room, where multiple girls sit dressed in veils at the ready, with Olive’s number (13) coming up on a digital signal board. The delighted Olive flaunts it in the face of the other disappointed wanna-be’s, strutting in front of them and bidding good bye. But before she comes out to her intended, Olive decides to apply a little “insurance” – her handy make-up kit.

For Better or Worser (Paramount/Fleischer, Popeye, 6/28/35 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.) – The first of a string of Popeye cautionary tales, entirely original, and one of the first to remind caution at considering marriage for the wrong reasons. Popeye is seen in his bachelor apartment, wearing an apron, attempting to make dinner. His cooking skills definitely don’t match his fighting skills – items burn, boil over, and fill the room with smoke. Disgusted, Popeye throws down the apron, and announces, “It’s no use! I have t’ get me a wife.” He walks down the street to a local matrimonial agency (accompanied by the musical cue, “Love is Just Around the Corner”). Coincidently, Bluto has reached the same idea, and is already inside. Photos of available spouses appear on a wall – and of course our two romantically-blind sailors both choose the ugliest one of all – Olive, whose back is turned in the photo. A buzzer is rung by an attendant to an adjoining room, where multiple girls sit dressed in veils at the ready, with Olive’s number (13) coming up on a digital signal board. The delighted Olive flaunts it in the face of the other disappointed wanna-be’s, strutting in front of them and bidding good bye. But before she comes out to her intended, Olive decides to apply a little “insurance” – her handy make-up kit.

Unlike Mess Production (1945), where she uses such a kit to transform herself into a living doll, Olive has not yet developed her skills – and manages to transform herself into something of a hideous monster, suitable only for wedding by Mr. Hyde. However, she pulls the veil in front of her face before appearing before the boys. Finding to her surprise that two suitors want her at once, Olive becomes the centerpiece for a tug of war and wild battle between the sailors. Justice of the Peace Wimpy is finally reached by Bluto, Olive in his grip, who demands a ceremony. Just before the vows can be exchanged, a battered Popeye enters behind them, and finally doses on his Spinach secret weapon. Knocking Bluto for the usual loop, Popeye bids the ceremony go on, with himself in Bluto’s place. As Wimpy reaches the crucial moment of asking if he will take Olive, Olive finally pulls back the veil – revealing her horrific makeup. Popeye shouts, “I do NOT!”, and races a hasty exit back to his apartment. Donning his apron, he resumes his cooking, singing, “I yam what I yam an’ I’ll be what I yam”, as the boil-over from a pot floods the room and consumes the entire frame, except his pipe, which toot-toots as we iris out to the anchor end card. Moral of the story appears to be, examine well your goods…or just go and hire a cook!

Dancing on the Moon (Paramount, Fleischer, Color Classic (2 strip Technicolor), 7/12/35 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Knietel, Roland Crandall, Animation), represents a masterpiece in Fleischer’s use of the “patent pending” turntable camera (also used in the dancing shoe scene of “Kids in the Shoe” above), which permitted 3-dimensional models to be shot both in front of and behind 2D drawings. (The actual patent submission can be viewed online – just look up the patent number from any early Superman cartoon and Google it.) Taking the concept of “honeymooning” to its outrageous extreme, several newlywed animal couples book passage on the “Honeymoon Express” – a Buck Rogers style rocket ship to the moon! Ground longshots depict an actual 3D model, while flying scenes include 2D animation. The cartoon is built around a title song that will stay in your head permanently – which the passengers will use as their dancing theme when they reach their destination. Among the passenger list are Mr. and Mrs. Cat – who are a trifle late, and race to make the flight. The combination door/gangplank raises, and Mr. Cat just barely squeaks his way into the hatch – but Mrs. Cat falls outside just as the ship takes off from an inclined ramp. She (voiced by Mae Questal) shouts after her spouse, “You left me on purpose, you alley cat!” The flight progresses, with all the couples happy except Mr. Cat, who bides his time in loneliness by playing card solitaire, then “cat’s cradle”. The man (or is it woman) in the moon greets them with Kate Smith’s standard radio greeting, “Hello, everybody!”.

On the moon, a dancing musicale ensues down a lovers’ lane of moon rocks and craters, with a giraffe couple noting “This is a great place for necking”, and the giraffe missus beckoning her hubby, a la Mae West, to “come up and see me sometime.” Mr. Cat, meanwhile can only listlessly twirl by himself without a dancing partner. Finally, it is time to go. A quick reversal of previous animation gets the spaceship back to earth. As the couples disembark, they look skyward with smiles, as a flock of storks approaches with a baby (it seems) for each couple. (These couples greet the stork favorably? Unusual for a cartoon – but of course, it’s only their firstborn.) As each couple walks away with their new arrivals, Mr. Cat meets the last stork, asking, “Gimme, gimme, gimme.” But the stork is empty-billed, and shakes his head that he has nothing to give. On this scene arrives Mrs. Cat, who, discovering she’s been shortchanged of both the trip and a baby, lays into her husband with punches bearing the sock of Jack Dempsey (good enough under the circumstances – Popeye wasn’t available that day).

The Merry Old Soul (Warner, Merrie Melodies (2 strip Technicolor), 8/17/35 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Directly borrowing from both Fleischer and himself, Freleng invites us to the royal wedding of Old King Cole to the Woman in the Shoe (maybe this is a prequel to the Fleischers’, suggesting that the stress of parenthood might have killed off Cole before the events depicted in the Color Classic above). The wedding goes off reasonably smoothly – but when Cole arrives at the Shoe (how come he doesn’t move her to the palace?), he finds every nook and cranny populated by children, surprising him with shouts of “Daddy!” Obviously, there’s a lot about her past the old woman conveniently “forgot” to tell him! Now, in parallel to Poor Papa, Cole is up to his elbows in household chores, scrubbing laundry, and manning another elaborate baby assembly line. Several gags are straight-lifted from “Shuffle Off to Buffalo”, including the roller towel, the flipover bar, the paper towel diapers and the stapler for a pin. To these, Freleng adds a watering trough to extend the bath, equipped with rotating car-wash style brushes, including two that converge from either side to wash inside the kids’ ears. Balloons are tied on to float them over to diapering station, where they hit a pin to drop the kids into the diapers. And a second flipping bar at the end of the conveyor intersects with a moving clothesline, flipping the kids into their nighties.

The clothesline then drops them into their respective rows of cradles. (The writers have fun finding sets of names to put on consecutive cradles, such as “Wynken”, “Blynken” “and” “Nod”, and “Nip” and “Tuck”). The cradles are powered by a drive shaft mounted into an old-fashioned pedal-driven sewing machine, so that Cole can rock them and sing a lullaby all at once. After one false start, he finally gets the kids to sleep, and settles down in an easy chair. Or so he thinks. Nip and Tuck are still awake, and sneak over to the sewing machine pedal, manipulating it at full speed until all the kids are thrown out of their cradles and onto Cole’s lap and feet. They all cry and wail, and Cole (who roughly resembles Oliver Hardy) can do nothing but break down into a Stan Laurel style cry too, as the camera irises out. No, Cole, it’s not a dream! (For original titles buffs, note that this is the only two-strip Merrie Melodie later edited for “Blue Ribbon” reissue for which the original titles have been recently rediscovered, with a live action opening of a storybook on which the main title and director/animator credits are embossed on the cover – sadly, the print shows substantial image deterioration with seemingly hundreds of blotchy white and blue green dots where emulsion seems to have been eaten away, and contains no end title. I wonder what a good digital cleanup could do for it.)

Don’t Look Now (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 12/30/36 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.), and Cupid Gets His Man (RKO Van Buren, Rainbow Parade, 7/24/36 – Tom Palmer, dir.). offer two more or those scarce and unusual “pro-marriage” viewpoints in a cartoon setting. Both provide nearly the definitive tributes to Valentine’s Day, and end with characters tying the knot/ In Avery’s twisted tale, a clever war of wits develops between Dan Cupid and a look-alike devilish imp, both of whom consider the holiday “My big day” – for romance for the former, mischief for the latter. While Cupid determinedly fires his arrows at pairs of prospective clients, the imp lays obstacles in their marital path, including secretly applying lipstick marks to the face and blonde hairs to the shoulder of a would-be beau, and later bribing several local kids to run to the groom in the middle of a wedding ceremony and yell, “Daddy! Daddy!” But Dan’s arrows seem to have a way of conquering all evils, and finally a well-placed shot hits the devil’s rear end. As the reconciled wedding couple return to the alter and are about to complete their ceremony, everyone is startled and ducks for cover. Coming down the aisle dressed in formal bowler hat is the imp – on his arm, a young female skunk (who was the only one during the cartoon that Cupid couldn’t seem to find a match for), tickled pink that she’s the next in line.

Cupid Gets His Man takes a unique and energetic look at the life of those love-cherubs – revealing that they are actually militarized in the manner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, complete with Dudley-Do-Right style mountie hats and coats, and pride themselves on always getting their man. Their headquarters is also inhabited by doc stork, who receives paperwork on every completed mission and then spins a carnival-style “Wheel of Fortune” which determines if they get a boy, girl, twins, etc. To commander Dan Cupid’s surprise, one cherub returns battered and with a black eye, announcing that he didn’t get his man, “He got me”. The resistant prospective couple turn out to be well-animated caricature counterparts of W. C. Fields and Edna Mae Oliver, who each sneer at the thought of marriage to anyone – especially each other. Dan Cupid himself decides to take charge of the case. Presenting himself to the troublesome two, he announces, “Stop this racket! No more strife. I’m gonna make you man and wife!”, and is appropriately hit in the face with a pie, then pelted with everything the couple can throw at him. But cupid is determined. Mustering his troops, scores of cherubs arise on heart-shaped “flying wing” aircraft armed with machine-gun arrow shooters.

Others rely on their own wings, but find trouble as Edna Mae pins their wings with several well-aimed clothespins shot from her backyard clothesline. The couple put up a vigorous fight in which many cherubs fall – but are ultimately rounded up at arrow-point, and sentenced to a firing squad. Steeling themselves for the shot, both take it – directly in the heart. The scene abruptly changes to a bright path upon the clouds, strewn with falling flower petals, to a castle in the air, with our couple decked out in medievally-formal finery. They finally exchange flowery compliments upon each other (including Edna Mae calling Fields “Romeo”, and Fields calling her “Toots” and “Chickadee”), and disappear down the primrose path together. Returning to headquarters, and proudly repeating his motto to “always get his man”, Cupid turns in his papers to doc stork. The Wheel of Fortune is spun – and comes up with a bell alarm announcing hitting the jackpot – quintuplets! (Recall that the Dionne quintuplets had recently made worldwide headlines.) Stamping the information on the couple’s paperwork, the stork recites aloud, “Boy…Boy…Boy…Boy, oh Boy, oh Boy!” The End.

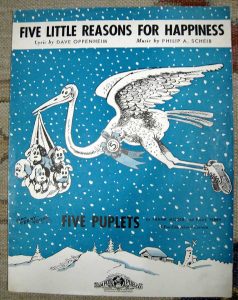

The arrival of the Dionne Quintuplets would be celebrated by several studios over a handful of years. Terrytoons would release Five Puplets (Educational, 5/17/35), one of the only of its episodes to spawn a published song. While a stork appears in its early sequences, he doesn’t even get one gag in making the delivery! The film further rips off nearly verbatim the Freleng conveyor belt from Buffalo and Merry Old Soul above, only adding to it an estra belt for dispensing of milk bottles. Oswald the Rabbit (at Lantz) would have recurring visits with a quintet of ducklings known as Fee, Fi. Fo, Fum, and Fooey (see for example, The Barnyard Five (1936) (with a brief cameo for a non-flying stork serving as a country doctor), Beach Combers (1936), The Birthday Party (1937), and his last black and white, Happy Scouts (1938)). Friz Freleng would feature five identical quints singing Our Old Man in The Coo Coo Nut Grove (Warner, Merrie Melodies,11/29/36).

The arrival of the Dionne Quintuplets would be celebrated by several studios over a handful of years. Terrytoons would release Five Puplets (Educational, 5/17/35), one of the only of its episodes to spawn a published song. While a stork appears in its early sequences, he doesn’t even get one gag in making the delivery! The film further rips off nearly verbatim the Freleng conveyor belt from Buffalo and Merry Old Soul above, only adding to it an estra belt for dispensing of milk bottles. Oswald the Rabbit (at Lantz) would have recurring visits with a quintet of ducklings known as Fee, Fi. Fo, Fum, and Fooey (see for example, The Barnyard Five (1936) (with a brief cameo for a non-flying stork serving as a country doctor), Beach Combers (1936), The Birthday Party (1937), and his last black and white, Happy Scouts (1938)). Friz Freleng would feature five identical quints singing Our Old Man in The Coo Coo Nut Grove (Warner, Merrie Melodies,11/29/36).

And Pluto would give us the most cautionary “tail” of the bunch with Pluto’s Quin-puplets (RKO, 11/26/37). (For title buffs: This was the first episode to be billed as starring Pluto, under the banner title, “Pluto the Pup” – original titles, featuring a unique headshot of the character, have been located on the “Erik” subchannel on YouTube – check ‘em out. Technically, though, this was not Pluto’s first solo, as a previous episode had been slipped into the Silly Symphony release calendar without a series banner, entitled Mother Pluto (UA, 1936).) Pluto, (without the benefit of clergy?) has finally tied the knot with Minnie’s pooch Fifi (previously seen in Puppy Love (1933) and The Dog-Napper (1934), and just this year making her triumphant small-screen return in Mickey Mouse’s short, “You, Me, and Fifi”), changing the sign over his doghouse to read “Mr. and Mrs. Pluto and Family”. Five little ones, all resembling their father, are at their feet. A passing man carrying a basket of sausages attracts their attention – and nostrils. Fifi runs off to see if she can beg them up a dinner, but demonstrates that all is not wedded bliss in her relationship with Pluto, snarlingly chasing him back to take care of the kids while she’s gone. Pluto expends a great deal of thought on how to keep the kids penned up in the doghouse, not realizing one sideboard is loose, allowing the kids an easy escape route. As they follow a worm across the yard, a board they’re walking on shifts loose and tumbles them into the open cellar door. There, they encounter a diabolical menace – a paint sprayer, hooked up to a tank of compressed air.

Pluto discovers their whereabouts, and attempts to attack the sprayer – only to have himself puffed up like a balloon from the disconnected airhose, to deflate when he lets go and be shot across the room, where he hits a wall underneath a shelf containing a jug marked “XXX”. The jug spills, and Pluto, swallowing most of it, is reduced to a drunken stupor. Meanwhile, the loose airhose encounters various paint cans, spraying in turn each of the puppies in a different color or pattern – including checks and polka dots. Fifi finally returns, with a string of sausages clutched in her mouth, only to be greeted by the vibrant Technicolor puppies. Her lips quiver in recoiling disgust, and she lets loose with a series of violent reprimanding yaps, sending the pups scattering. At this moment, a stumbling bumbling Pluto emerges from the basement, nearly as colorful as the pups from the wet paint. He greets Fifi with a hiccup that tells her with one sniff that he’s intoxicated. Her yaps erupt in an even more violent tirade. The scene dissolves to nighttime, with a still grumbling Fifi the only occupant of the doghouse. On the other side of the yard, a groggy Pluto is left to sleep outside in the remains of a half-broken barrel, with the pups on top of him rolling back and forth in the barrel with each of Pluto’s snores. I guess being proverbially “in the doghouse” would have been preferable under these circumstances.

Bunny-Mooning (Paramount, Fleischer Color Classic, 2/12/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Myron Waldman, Edward Nolan, anim.), only deserves glancing honorable mention. Another fairly straight depiction of an animal wedding, in the manner of “Wedding Bells”, above, with no plotline. Basically an assemblage of random gags strongly resembling what Paramount learned to do in their sleep to pad the allotted time for subsequent Technicolor Screen Songs. Neither animation quality nor individual gags distinguish this one, and the only thing anyone seems to remember about it is its theme song, “Heading For a Wedding”, which even so, doesn’t hold a candle to “Dancing On the Moon”.

Swing Wedding (MGM, Hugh Harman-Rudolf Ising, 2/13/37). Two wedding cartoons released only a day apart? And it’s not even spring! This one, far exceeding the previous day’s output, seemingly presents as its only moral, “Faint heart ne’er won fair lady.” In this follow-up to the previous year’s Oscar nominee, “The Old Mill Pond” (1936), an all-frog cast (caricatures of famous black performers of the day) converge to witness Minnie the Moocher’s wedding day (based on the popular song of the same name). The intended groom, Smokey Joe (a caricature of stereotype slowpoke Stepin Fetchit), is in no hurry to get to the ceremony, and seems entirely recalcitrant about the whole thing. While Minnie grows impatient at Joe’s absence, up from the pond rises the frog equivalent of Cab Calloway and his orchestra. Cab’s energy and gyrations entrance Minnie, and when he suggests himself as a spousal substitute, she and her bridesmaids start strutting down the aisle with Calloway on her arm.

Meanwhile, Foghorn (a rotund frog voiced a la Louis Armstrong, complete with cornet, who performs Louis’s hit, “Sweethearts On Parade”), has intercepted Joe, and taking his side of the situation, decides Joe must confront his new rival. As a minister asks if anyone has reason why this couple should not be wed, Foghorn speaks up, bringing “my boy” Joe to the altar. Minnie is unimpressed – until Foghorn decides all that Joe needs is a little inspiration. Blowing hot licks on his cornet to the tune of “Running Wild”, Foghorn drives Joe into an ear-to-ear grin and a fit of eccentric dancing. Calloway knows that he’s licked, and all he can do is spin back to his orchestra and accompany the melee. A wild and destructive musical finale ensues, with most of the instruments shattered to bits in the fury of the music (including an infamous sight gag resembling drug culture mainlining, slipped through so fast the censors never caught it), and Foghorn blows so hard he puffs up like a balloon, then deflates, sweeping him backward into the pond, where he sinks below the waves, exhausted, but happily murmuring, “Swing…..swing…..”

Porky’s Romance (Warner, Looney Tunes, Porky Pig, 4/3/37 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – “Introducing Leon Schlesinger’s new cartoon star, Petunia Pig!” shouts an announcer in the prologue before the titles. Petunia (who appeared in this design only in Tashlin-directed episodes, remaining to be redesigned by Bob Clampett into her present-day form) would actually never achieve much stardom on screen, appearing in only three Tashlin cartoons (including The Case of the Stuttering Pig (1937) and Porky’s Double Trouble (1937)) and a handful of Clampett’s (including Naughty Neighbors (1939) and Porky’s Picnic (1939) – she had been “penciled in” for appearance in the storyboards for Porky’s Party (1938), but was ultimately “erased” from its cast), and would have her stardom mostly in the comic books, and once on record (see Mel Blanc’s “That’s All, Folks” (Capitol F1948), featured on James Parten’s “Needle Drop Notes” article, “Puddy Tats Here…Puddy Tats There” on this site, voiced by Wee Bonnie Baker, former vocalist for the Horace Heidt band). This is one of the more well-known marital cartoons, written extensively upon by Leonard Maltin in his outstanding treatise, “Of Mice and Magic”, for its dynamic editing techniques and clever camera angles.

For our purposes, it follows squarely on the heels of Mickey’s Nightmare, depicting Porky, who has loved from afar and lost, attempting to commit suicide (enter the Cartoon Network censors to try to keep this one from being seen intact) by hangman’s noose suspended to a tree – except he’s too fat for the limb (a lifted gag from Laurel and Hardy’s “The Devil’s Brother” (1933)) and takes it down with him, clunking him on the head. He passes out, dissolving to a wedding sequence with Petunia almost identical to Mickey Mouse’s above, and they honeymoon at the Honeymoon Hotel, which apparently has been rebuilt since 1934 to house larger guests. In a parody of the “March of Time” radio program (a news half-hour sponsored by Time Magazine), the offscreen announcer returns (possibly Billy Bletcher), accompanied by words on screen as he shouts, “TIME MUNCHES ON!” The title lingers on screen for a few beats as we hear loud chewing sounds from off-camera. The letters disappear and we iris in to Petunia, lounging on a sofa with her dog at her feet. Both have bloated up to be big as a house, and are endlessly devouring boxes of candy (set to the background music of a delightfully sarcastic rendition of “Oh, You Beautiful Doll”). In the next room, Porky is observed in apron, attempting to handle all household chores all by himself – washing, ironing, and cooking – and burning both food and holes in clothes in the process, plus breaking all the dishes.

For our purposes, it follows squarely on the heels of Mickey’s Nightmare, depicting Porky, who has loved from afar and lost, attempting to commit suicide (enter the Cartoon Network censors to try to keep this one from being seen intact) by hangman’s noose suspended to a tree – except he’s too fat for the limb (a lifted gag from Laurel and Hardy’s “The Devil’s Brother” (1933)) and takes it down with him, clunking him on the head. He passes out, dissolving to a wedding sequence with Petunia almost identical to Mickey Mouse’s above, and they honeymoon at the Honeymoon Hotel, which apparently has been rebuilt since 1934 to house larger guests. In a parody of the “March of Time” radio program (a news half-hour sponsored by Time Magazine), the offscreen announcer returns (possibly Billy Bletcher), accompanied by words on screen as he shouts, “TIME MUNCHES ON!” The title lingers on screen for a few beats as we hear loud chewing sounds from off-camera. The letters disappear and we iris in to Petunia, lounging on a sofa with her dog at her feet. Both have bloated up to be big as a house, and are endlessly devouring boxes of candy (set to the background music of a delightfully sarcastic rendition of “Oh, You Beautiful Doll”). In the next room, Porky is observed in apron, attempting to handle all household chores all by himself – washing, ironing, and cooking – and burning both food and holes in clothes in the process, plus breaking all the dishes.

A shot of another room (the nursery) reveals a room full of cradles, all marked “Porky Pig Jr.” with identical offspring, all crying. Petunia scolds Porky to shut those kids up. Porky tries rocking them , to no avail, apologetically responding “I’m d-d-d-d-doing the b-b-b-best that I can.” His best is not enough, as Petunia enters with rolling pin, calls him a worm, and starts bashing him over the head, as their offspring watch as a rooting section, chanting in unison, “Give it to heem, mama! Give it to heem!” The scene dissolves away, back to the present. Petunia has found Porky and his suicide note nearby attesting to his love for her. She has relented, and announces that she’s so happy to be with him again, she will marry him. But all that Porky can see in his mind’s eye is images of his dream. He zips out of scene over the horizon – in an afterthought, zips back again, and takes back the box of chocolates he had given her earlier in the cartoon, disappears again – and in a final afterthought, zips back one more time to deliver a swift kick to Petunia’s aggravating dog, then disappears for good.

A sidelight mention is deserved for Clock Cleaners (Disney, RKO, Mickey Mouse, 10/15/37 – Ben Sharpsteen, dir.), featuring one of cartoondom’s only storks who doesn’t give a hoot about delivering babies – he just wants to hole up in the clock tower for a good night’s sleep. But when Mickey tries to evict him, he “delivers” Mickey by grabbing him up by his work pants like a bundle, and abruptly dropping him out the window. (For those who remember collecting 8mm, Disney cheated purchasers for years on this title by snipping out this entire sequence in so-called “complete” editions to save on footage from the long running time of the film – if you have one of the early prints with stork still in, you’re one of the lucky ones.)

Cleaning House (MGM, Captain and the Kids, 2/19/38 – Robert Allen, dir.) – As with many episodes of this series, this film feels cluttered – by more than what the family’s cleaning up. In apparent over-determination to pick up the pace, the fledgling MGM house studio seemed to pile up unnecessary gags and plot points that had the effect of disrupting a coherent narrative. Amidst a tale of Papa Captain playing sick to avoid housework, and Hans and Fritz posing as doctors to “cure” him, we are introduced for no apparent reason to two real doctors – one avian, one human – whose door sign reads “Dr. Stork and Dr. Quak – Cradle to the grave.” Quak is the human one – a caricature of W.C. Fields, who spends his idle time practicing with a ventriloquist dummy voiced like Charlie McCarthy. Stork never speaks – just has an irritating laugh – and though the distress call from Mama is only to aid Papa, Stork seems determined to tag along and deliver a baby without request. Finding none is his present supply, he spends the remainder of the cartoon attempting to deliver to Mama the ventriloquist dummy! Did I tell you? Unnecessary.

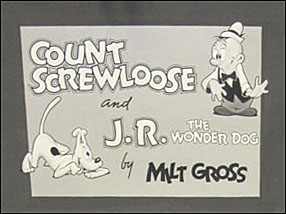

Wanted: No Master (MGM, Count Screwloose & J.R. the Wonder Dog, 3/18/39, Milt Gross, Dir.) -The first of a number of epics to depict the pitfalls of marriage for greed. J.R. is fed up with the Count’s company – as the Count has the aggravating habit of devouring every morsel of food on the breakfast table before J.R. can get it to his lips. As Screwloose reads the inner pages of the morning paper, J.R. notices two items on the outer pages – a want ad by a wealthy widow seeking a husband (except her picture reveals that she is about as homely as Long John Silver from the studio’s preceding “Captain and the Kids” series), and a picture of a Hollywood movie queen. J.R. carefully cuts out the movie star’s picture, then pastes it over the widow’s picture with some pancake syrup. As Screwloose flips the page to read the outer sheet, his eyes bug out and he let’s out with a “Woo Woo!” He’s hooked, line and sinker, into meeting the widow.

Upon arriving at her address, he almost enters the adjoining flat – which, to make things convenient, is occupied by a Justice of the Peace. Finding the right doorbell, Screwloose rings – and is immediately whisked inside as the door is revolving! Inside the door, the Count observes a “Hope Chest”, then to its right, another “Hope Chest”, and finally a third “I Hope I Hope I Hope Chest” (reference to a radio catch-phrase of Al Pearce as country bumpkin salesman Elmer Blurt – see Warner’s Jungle Jitters (1938) for a dead-on caricature). On the opposite wall, the Count sees a row of 11 framed wedding pictures, each depicting the widow – with a different husband. The twelfth frame features the widow (still in bridal gown), all by herself. Screwloose starts to get the idea this isn’t the girl of his dreams from the newspaper photo, and pulls out the paper from his pocket to examine it more closely. Suddenly the 12th photo comes to life – it’s the widow herself in the frame, who looking over the Count’s shoulder, sees the doctored newspaper. Stating, “Of all things!”, she reaches down and peels off the movie star photo, revealing to the Count the true setup. A wild chase ensues, highlighted by: a closet in which Screwloose ducks, rigged with a hole in the door for his head to protrude through when he peeks out and the door is slammed on him by the widow, set up like a beachfront photo studio cutout, painted on the door so that he appears to be wearing a top hat and tuxedo.

Upon arriving at her address, he almost enters the adjoining flat – which, to make things convenient, is occupied by a Justice of the Peace. Finding the right doorbell, Screwloose rings – and is immediately whisked inside as the door is revolving! Inside the door, the Count observes a “Hope Chest”, then to its right, another “Hope Chest”, and finally a third “I Hope I Hope I Hope Chest” (reference to a radio catch-phrase of Al Pearce as country bumpkin salesman Elmer Blurt – see Warner’s Jungle Jitters (1938) for a dead-on caricature). On the opposite wall, the Count sees a row of 11 framed wedding pictures, each depicting the widow – with a different husband. The twelfth frame features the widow (still in bridal gown), all by herself. Screwloose starts to get the idea this isn’t the girl of his dreams from the newspaper photo, and pulls out the paper from his pocket to examine it more closely. Suddenly the 12th photo comes to life – it’s the widow herself in the frame, who looking over the Count’s shoulder, sees the doctored newspaper. Stating, “Of all things!”, she reaches down and peels off the movie star photo, revealing to the Count the true setup. A wild chase ensues, highlighted by: a closet in which Screwloose ducks, rigged with a hole in the door for his head to protrude through when he peeks out and the door is slammed on him by the widow, set up like a beachfront photo studio cutout, painted on the door so that he appears to be wearing a top hat and tuxedo.

The widow pulls up a camera and tripod and poses in front of it with Screwloose. The camera must be an early Polaroid, as she pulls out from the back of the camera, already framed, a self-developing next wedding photo of her and the Count. Screwloose runs to another closet door and opens it – only to find about a dozen kids of various ages, shouting “Hiya, paw!” (Shades of King Cole’s discoveries in “Merry Old Soul” above.) The Count retreats, and ma widow tells the children, “You kids keep outta this!” The justice of the peace enters at intervals, asking if the lovebirds are “ready?”, only to be repeatedly told “not yet” by the prospective bride. On his final entry, the justice opens a door at the opportune time to smash the Count into and through the wall behind it, knocking him cold. The widow now announces she’s “ready”, and the justice peels off a paper roll, in the manner of a roll of paper towels, a certificate of marriage. Back at home, J.R. is laughing himself silly at what he’s done to the Count, and having the place all to himself. The Count’s cook, seen in the original breakfast scene, announces that dinner is served. But just as J.R. is about to dine, there is a knock at the front door. Enter the Count, the new missus, and all the kids, together with their baggage and wardrobes – they’re all moving in with J.R.! As they all scurry to the dinner table to again devour every scrap of food, J.R. stands in front of a mirror and starts punching himself in the face until he falls to the floor – and his reflection reaches out of the mirror and adds a good swift kick in his rear end, as we iris out. Clever and fast paced – the better of the only two cartoons produced in this “series”.

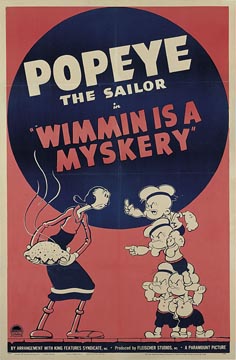

Wimmin Is a Myskery (Paramount/Fleischer, Popeye, 6/7/40 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowshy, Joe d’Igalo, anim.) – Story man Ted Pierce (in a rare departure from Warner Brothers) brings us another tale of marital woe. Popeye has gotten up the nerve again to propose to Olive, who for once is not having makeup troubles. But the usually overanxious Olive is uncharacteristically coy today, and insists on sleeping on it, promising to give the sailor her answer in the morning. In the same manner as Mickey’s Nightmare, she dreams of a rose covered honeymoon cottage, inside which she engages in “washing” the family portraits, scraping suds off a large picture of Popeye, and four smaller frames, each bearing an identical photo of her “little angels – chips off the old blockhead”. The frames reveal their names: Pep-eye, Pup-eye, Pip-eye, and Peep-eye. (These four characters would of course later be retreaded in the guise of Popeye’s “nephews” of unknown origin, with “Pep-eye” rechristened “Poop-eye”.) A crash in the kitchen sends Olive on the run, to find the kitchen interior roughly resembling a war zone. “Who did this?”, she shouts. The boys appear in respective kitchen cabinets, taking pieces of the sentences, “I must” “confess”, “I made” “a mess”. Sending them upstairs, Olive next sees what is to her an all too familiar crack developing in the ceiling plaster. The boys are upstairs raising and lowering a folding Murphy bed, using its foot as a nutcracker. Chased out again, they notice a pie on a windowsill. Olive catches them just before they can steal it, announcing it’s for Popeye’s dinner.

One of the kids comments “It’s pop’s pie!”, giving them an idea. Into a bedroom closet, and out with Popeye’s hat, shirt, and trousers. Two man the shirt, two in the pants, and stacked as a foursome, impersonate their old man, song and all, claiming he is famished for pie. The ruse works – until they cross the living room, reaching a table. Forgetting they’re supposed to be one person, half of them go under the table, half over it. Olive is furious and gives chase. The kids try a retreat out an open window, but Olive slams it shut, catching them while halfway through, and starts tanning their backsides. On the outside the kids’ heads react: “Rats in a trap!” “It’s mutiny!” “This is serious.” “What would pop do?” They all know the answer to that question: “He’d bust out the spinach!” Despite their usual notorious aversion to spinach in later episodes, the four cheerily take their respective doses here. They develop the power of flight, and soar into the air, pulling the window loose from its framing. Entering back into the house like a precision flight team, they swoop and dive at Olive, then confront her. Olive tremulously attempts to avoid her fate, saying “Don’t you touch me. I’m your mother!” The words have no effect. One uses her as a jump rope. Others start tossing her around like a medicine ball. Then they develop a teamwork of throws, passes, sliding her down banisters, etc. that places her in the unwilling role of circus acrobat. She lands exhausted on a couch, and is roused by a bell back to the real world, where Popeye beckons below to find out if she will sail with him on the sea of matrimony. Her answer – not if he was the last man in the world. Left jilted, Popeye sings, “It’s proven through hiskery that wimmin is a myskery, says Popeye the sailor man!” (Later reworked in Technicolor with different, less funny gags, and only two kids, but the same basic premise, in Bride and Gloom (7/2/54 – I Sparber, dir.). If only Popeye’s “real” offspring had had half the feistiness of Olive’s dream kids in the awful Hanna-Barbera TV venture, “Popeye and Son”, years later.

One of the kids comments “It’s pop’s pie!”, giving them an idea. Into a bedroom closet, and out with Popeye’s hat, shirt, and trousers. Two man the shirt, two in the pants, and stacked as a foursome, impersonate their old man, song and all, claiming he is famished for pie. The ruse works – until they cross the living room, reaching a table. Forgetting they’re supposed to be one person, half of them go under the table, half over it. Olive is furious and gives chase. The kids try a retreat out an open window, but Olive slams it shut, catching them while halfway through, and starts tanning their backsides. On the outside the kids’ heads react: “Rats in a trap!” “It’s mutiny!” “This is serious.” “What would pop do?” They all know the answer to that question: “He’d bust out the spinach!” Despite their usual notorious aversion to spinach in later episodes, the four cheerily take their respective doses here. They develop the power of flight, and soar into the air, pulling the window loose from its framing. Entering back into the house like a precision flight team, they swoop and dive at Olive, then confront her. Olive tremulously attempts to avoid her fate, saying “Don’t you touch me. I’m your mother!” The words have no effect. One uses her as a jump rope. Others start tossing her around like a medicine ball. Then they develop a teamwork of throws, passes, sliding her down banisters, etc. that places her in the unwilling role of circus acrobat. She lands exhausted on a couch, and is roused by a bell back to the real world, where Popeye beckons below to find out if she will sail with him on the sea of matrimony. Her answer – not if he was the last man in the world. Left jilted, Popeye sings, “It’s proven through hiskery that wimmin is a myskery, says Popeye the sailor man!” (Later reworked in Technicolor with different, less funny gags, and only two kids, but the same basic premise, in Bride and Gloom (7/2/54 – I Sparber, dir.). If only Popeye’s “real” offspring had had half the feistiness of Olive’s dream kids in the awful Hanna-Barbera TV venture, “Popeye and Son”, years later.

The Henpecked Duck (Warner, Porky and Daffy, 8/30/41, Robert Clampett, dir.) – possibly the only cartoon ever to deal with the dreaded subject of – divorce! In this “simulated session of Divorce Court”, the honorable Judge Porky Pig (did he run for this office or was he a political appointee?) presides over the case of “Duck vs. Duck”. Taking a back seat to the antics of Daffy, Porky listens as Mrs. Duck rants about slaving over a hot nest for the best years of her life, and demands a divorce. Asked to describe her cause, she recounts the day she left Daffy to tend the nest and the egg for their offspring to be, ending her instructions to Daffy with “And if you don’t I’ll wring your fool neck!” Daffy (well henpecked as in the title), only dares talk back to her when he thinks she’s out of earshot – but when she reappears unexpectedly reverts instantly to form, saying only “Yes, m’love.” Left alone, and entirely bored, Daffy improvises a pretend magic show, manipulating the egg between his fingers, then clamping both hands over it and seeming to squeeze it until it disappears from sight. Reciting the magic words, “Hocus pocus, flippity flam, a razz-a-ma-tazz, and alakazam!”, the egg magically reappears between his fingertips. Impressed by his own skill, Daffy tells the audience, “If Major Bowes could only see me now” (reference to the host of a famous radio Amateur Hour, later inherited for television by Ted Mack), and decides to repeat the act, embellishing this time by demonstrating that under the feathers on each arm he has “Nothing up here” and then pointing to his head and continuing “…and nothing up here.”

He repeats the process, recites the magic words – and comes up with an empty hand. He tries again – and again – and again – and still no egg. He continues over and over again in a panic, between crying jags, and asks the audience, “Is there a magician in the house?”, until several hours later, he has almost lost his voice. Hearing “the little woman” approaching, he attempts to fool her by replacing the egg with a doorknob – but the ploy fails to convince. Back in the present, before Porky rules, Daffy finally finds the courage to ask for “just one more chance”. Muttering a prayer under his breath before a hushed courtroom audience, he repeats the incantation one more time – and the egg finally reappears. In the most memorable line of the film, an old hen in the audience (in a vocal impersonation of Zasu Pitts), breaks the fourth wall by stating to us, “Alakazam and you get an egg? Oh dear….And for fifteen years I’ve been doin’ in the hard way!” (This punch line was reused at least once by Robert Mckimson when a trick egg housing Henery Hawk keeps making surprise appearances in Foghorn Leghorn’s Crowing Pains (1947).) The Ducks are reunited, as the egg hatches, with a little black duckling grabbing Porky’s spectacles and gavel, and announcing, “Case dismissed. Step down.”

To be continued. See you next week.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

There is some really good animation in that Count Screwloose cartoon!