Only a few days left until Valentine’s Day. Faint heart never won fair lady. So gather ye rosebuds while ye may, from the dazzling bouquets of animated blooms from Hollywood’s Golden Era discussed below.

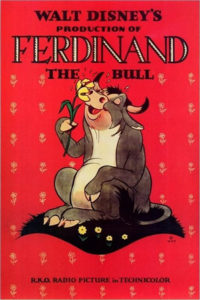

Ferdinand the Bull (Disney/RKO, 11/25/38, Dick Rickard, dir.), Disney’s well-known Oscar-winning adaptation of Munro Leaf’s famous children’s novel, necessarily deserves inclusion in this article for its central focus on flowers as a symbol of pacificism and tranquility. Even the film’s titles, custom-designed rather than billing the film as a Silly Symphony, are modeled directly from the floral wallpaper-like pattern used on the cover of the original book – and to this day on all reprints I’ve seen. Ferdinand is an unusual loner – a bull who sees no point in the other young bulls’ fixation with charging around and butting their heads together. Instead, Ferdinand prefers a peaceful life of loafing all day under a cork tree (comically designed as a tree sprouting already pre-shapen bartender’s corks) and smelling the flowers just quietly. One day five men come to the pasture seeking new contenders for the bullfight arena. While the other bulls vie for attention, the men scoff that none will do. Ferdinand, having no intention of competing, attempts to settle down under his usual tree – but picks this unlucky day to sit on a bumblebee in one of the flowers. Painfully stung, Ferdinand runs around as if mad, knocking other bulls aside as if bowling pins, uprooting trees, etc. – and the five men select him as fierceness incarnate.

Ferdinand the Bull (Disney/RKO, 11/25/38, Dick Rickard, dir.), Disney’s well-known Oscar-winning adaptation of Munro Leaf’s famous children’s novel, necessarily deserves inclusion in this article for its central focus on flowers as a symbol of pacificism and tranquility. Even the film’s titles, custom-designed rather than billing the film as a Silly Symphony, are modeled directly from the floral wallpaper-like pattern used on the cover of the original book – and to this day on all reprints I’ve seen. Ferdinand is an unusual loner – a bull who sees no point in the other young bulls’ fixation with charging around and butting their heads together. Instead, Ferdinand prefers a peaceful life of loafing all day under a cork tree (comically designed as a tree sprouting already pre-shapen bartender’s corks) and smelling the flowers just quietly. One day five men come to the pasture seeking new contenders for the bullfight arena. While the other bulls vie for attention, the men scoff that none will do. Ferdinand, having no intention of competing, attempts to settle down under his usual tree – but picks this unlucky day to sit on a bumblebee in one of the flowers. Painfully stung, Ferdinand runs around as if mad, knocking other bulls aside as if bowling pins, uprooting trees, etc. – and the five men select him as fierceness incarnate.

Built up by advance poster advertising at the bullfight arena, Ferdinand is prodded into a stadium full of fans expecting to see the gorefest of the century. The picadors hide in fright. The matador is scared stiff (literally freezing in motionless rigid pose of terror). But the matador holds in his hand a bouquet of flowers thrown by a lovely señorita – and Ferdinand becomes fixated on the bouquet. Forgetting everything else going on around him, Ferdinand charges into the center of the ring, but lays no blow on the defenseless matador. Instead, as the matador drops the bouquet, Ferdinand sits down quietly next to it – “and smelled.” No amount of begging, pleading, taunting, or making funny faces at Ferdinand will get him to do a thing except “smell”. Breaking his sword in little pieces to vent his frustration, the matador insists that Ferdinand “Do SOMETHING! GIVE IT TO ME!” He tears away his shirt, leaving himself bare-chested and defenseless, so that at least he will die a hero. But on his chest is a tattoo of a large flower, with the matching woman’s name “Daisy”. (Hey Donald – you better keep an eye on your girlfriend.) Transfixed at the lovely sight, Ferdinand finally acts – giving the matador a huge sloppy slurping kiss across his chest and face. Narrator Don Wilson (master of ceremonies for decades on The Jack Benny Program) states in delightful vocal overacting, “The matador was so mad he cried, because he couldn’t show off with his cape and sword”. So Ferdinand is carted home without an incident. “And for all I know, he is still sitting under his favorite cork tree, smelling the flowers just quietly. He is very happy.”

Don Wilson’s narration was obviously enjoyed by Disney, and likely contributed greatly to setting the right mood to gain this film its Oscar. Don’s reward was a string of additional voice-over gigs in the late 1940’s and/or early 1950’s, when Disney signed a deal with Capitol records to create a series of storyteller record sets and singles based on various past Disney successes, with heavy focus upon the Silly Symphonies. No doubt with Walt’s blessing, Don Wilson was selected as the regular narrator for nearly this entire series of recordings – including a record version of “Ferdinand”. His reads continue to exhibit the same charm as the film track – gently aimed toward a child audience – but never to the point of being cloying and condescending, as was the norm for many a children’s radio entertainer during the 1940’s.

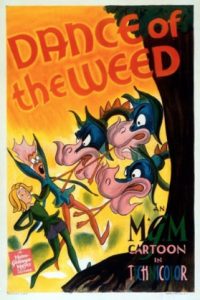

Dance of the Weed (MGM, 1/7/41 – Hugh Harman/Jerry Brewer, dir.), is sort of Scott Bradley’s chance to play Carl Stalling, with a project growing from an idea similar to Stalling’s inspiration to devise the Silly Symphony series at Disney. What if, thought Bradley, a cartoon was created from writing a score first, then setting animation to it, rather than the other way around? The result was this festival of nature, with Bradley taking a pivotal role in idea creation and story development. The inspiration for the film was obviously borrowing another “leaf” from Disney, who had just previously premiered his “Concert Feature”, rechristened “Fantasia”. Though Disney’s film took a while to recoup its investment, it was still regarded as a prestige project within the industry – enough so that Bradley was no doubt anxious to get to write his own little mini-symphony for this work. (Bradley had in fact come even closer to mimicking the Disney masterpiece in a previous project, set to an existing light-classical work, in MGM’s “The Blue Danube” (10/28/39), released in something of a race to premiere ahead of Disney’s feature.)

Dance of the Weed (MGM, 1/7/41 – Hugh Harman/Jerry Brewer, dir.), is sort of Scott Bradley’s chance to play Carl Stalling, with a project growing from an idea similar to Stalling’s inspiration to devise the Silly Symphony series at Disney. What if, thought Bradley, a cartoon was created from writing a score first, then setting animation to it, rather than the other way around? The result was this festival of nature, with Bradley taking a pivotal role in idea creation and story development. The inspiration for the film was obviously borrowing another “leaf” from Disney, who had just previously premiered his “Concert Feature”, rechristened “Fantasia”. Though Disney’s film took a while to recoup its investment, it was still regarded as a prestige project within the industry – enough so that Bradley was no doubt anxious to get to write his own little mini-symphony for this work. (Bradley had in fact come even closer to mimicking the Disney masterpiece in a previous project, set to an existing light-classical work, in MGM’s “The Blue Danube” (10/28/39), released in something of a race to premiere ahead of Disney’s feature.)

Plot focuses on a lonely, gangly and freckle-faced boy weed who longs for a life of romance – or even a casual friend. Other flora treats him as an outsider. Pussy willows snarl at him. Violets shrink from him. Water lilies hide behind marsh leaves, then swim away out of his reach. But as he sadly looks at his reflection in the water, he sees a vision of loveliness next to him. A curious female flower, with shapely stem and delicate orange petals resembling a tutu, is looking over his shoulder. Upon being discovered, she shyly flits away into the forest. The instantly smitten weed follows, and discovered a flowered meadow, where the girl dances as prima ballerina amidst a troupe of other dancing lovelies. A magnificently graceful choreographed ballet follows, representing about the finest animation that any major studio could offer. The weed attempts to join the dance (even using two leaves as props in something of a Sally Rand fan dance), but is ushered aside by the chorus dancers – however, the little star still offers gestures of encouragement, coaxing him in a coy feminine way to remain. She allows him to play a little hide-and-seek with her amidst the mushrooms. But a stiff wind arises, sending her spinning in a spiral – and blowing away her beautiful orange petals.

Embarrassed to be seen in her natural green, she tries to hide, but the weed follows. They are both blown into the air on a leaf, the girl coming down in a strange and mysterious part of the woods, inhabited by the vicious three-headed “snap-dragon”. The weed intervenes to pull the girl out of harm’s way, then comes up with various diversions to slow the snapdragon down, including blowing pollen up its noses, and spraying it with milk from a milkweed. The dragon is finally subdued, as the weed extends spider web between two stems and catches the villain in the net. The girl rewards him with a kiss, and together, they dance their way back to the weed’s marshland home near the stream. But things don’t seem so dull and gloomy there any more, now that his girl has decided to stay. They sit together on the rocks, while the weed pulls down a leaf between the audience and themselves for privacy – but the camera pans to the water surface, where the reflection reveals a glimpse of the weed embracing his girl affectionately, before a blossom falls on the water surface and obscures the view for the fade out.

Embarrassed to be seen in her natural green, she tries to hide, but the weed follows. They are both blown into the air on a leaf, the girl coming down in a strange and mysterious part of the woods, inhabited by the vicious three-headed “snap-dragon”. The weed intervenes to pull the girl out of harm’s way, then comes up with various diversions to slow the snapdragon down, including blowing pollen up its noses, and spraying it with milk from a milkweed. The dragon is finally subdued, as the weed extends spider web between two stems and catches the villain in the net. The girl rewards him with a kiss, and together, they dance their way back to the weed’s marshland home near the stream. But things don’t seem so dull and gloomy there any more, now that his girl has decided to stay. They sit together on the rocks, while the weed pulls down a leaf between the audience and themselves for privacy – but the camera pans to the water surface, where the reflection reveals a glimpse of the weed embracing his girl affectionately, before a blossom falls on the water surface and obscures the view for the fade out.

While not an action cartoon or a belly-laugh getter, there is something serene and pleasantly beautiful about this little mini-masterpiece (though the experiment would never be repeated again at MGM). Catch it when in the right mood for the kind of entertainment it offers, and you will not be disappointed.

Bambi (Disney/RKO, 8/21/42), offers us the iconic moment when Thumper the rabbit attempts to teach the young Bambi to talk, and to discover what a flower is. Showing him a patch of blooms, he teaches Bambi the name, then tells him they’re “purty” and demonstrates by smelling them. Bambi attempts to imitate, but instead of smelling petals, comes nose-to-nose with the most unlikely critter he would want to encounter beneath the floral petals – a young skunk. For lack of a vocabulary, the eager Bambi instantly calls him “Flower!” Thumper nearly dies laughing, doubling over in uncontrollable giggles. He is about to spill the beans as to what the animal is, but “Flower” interrupts him, and in a shy demeanor states, “Oh that’s all right. He can call me a flower if he wants to. I don’t mind.” Later, in the winter, the name starts to fit, as Bambi and Thunper discover Flower bedding down in a hole for a winter’s hibernation. “What’cha doin’ that for?”, they ask him. The skunk replies, “All us flowers sleep in the winter.” By the way, how many people remember that the adult Flower appearing later in the movie was voiced by Disney veteran and character actor Sterling Holloway (Winnie the Pooh), in only his second voice-over role for the studio?

Bambi (Disney/RKO, 8/21/42), offers us the iconic moment when Thumper the rabbit attempts to teach the young Bambi to talk, and to discover what a flower is. Showing him a patch of blooms, he teaches Bambi the name, then tells him they’re “purty” and demonstrates by smelling them. Bambi attempts to imitate, but instead of smelling petals, comes nose-to-nose with the most unlikely critter he would want to encounter beneath the floral petals – a young skunk. For lack of a vocabulary, the eager Bambi instantly calls him “Flower!” Thumper nearly dies laughing, doubling over in uncontrollable giggles. He is about to spill the beans as to what the animal is, but “Flower” interrupts him, and in a shy demeanor states, “Oh that’s all right. He can call me a flower if he wants to. I don’t mind.” Later, in the winter, the name starts to fit, as Bambi and Thunper discover Flower bedding down in a hole for a winter’s hibernation. “What’cha doin’ that for?”, they ask him. The skunk replies, “All us flowers sleep in the winter.” By the way, how many people remember that the adult Flower appearing later in the movie was voiced by Disney veteran and character actor Sterling Holloway (Winnie the Pooh), in only his second voice-over role for the studio?

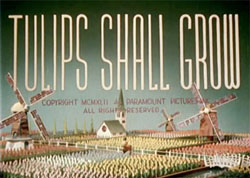

Tulips Shall Grow (George Pal/Paramount, Madcap Models, 1/26/42), is Pal’s masterpiece about Hitler’s invasion of Holland. The tulips do not take on personalities, but serve as a sort of symbolism for the freedom of nature and the way that things used to be in Pal’s native Europe. As we follow the musical romance of Jan and Janette amidst the land of windmills, suddenly the fanciful scene is disrupted entirely by the arrival of the invading “Screwball Army”. The Screwballs, entirely constructed of metal balls, nuts and bolts, had previously appeared in 1941’s “Rhythm in the Ranks” (reviewed in my previous post, “The Invisible Article”), in more traditional and comic form. But this time they take on a darker, more sinister overtone. Led by a goose-stepping general with a chest full of medals, the army pulls out all the stops to invade the peaceful land. Infantry troops trample fields and threaten with bayonets. Eerie planes highlighted in blacklight photography swoop from the darkened skies. Armored divisions are airlifted by the planes and dropped with oversize umbrellas that serve as parachutes, then roll over everything in sight. Jan and Jannette race one step ahead of the onslaught, but become separated. Most of Janette’s windmill is laid in ruins, while a cake Jan had given her as a gift is crumbled in symbolic fashion beneath the tank treads.

Tulips Shall Grow (George Pal/Paramount, Madcap Models, 1/26/42), is Pal’s masterpiece about Hitler’s invasion of Holland. The tulips do not take on personalities, but serve as a sort of symbolism for the freedom of nature and the way that things used to be in Pal’s native Europe. As we follow the musical romance of Jan and Janette amidst the land of windmills, suddenly the fanciful scene is disrupted entirely by the arrival of the invading “Screwball Army”. The Screwballs, entirely constructed of metal balls, nuts and bolts, had previously appeared in 1941’s “Rhythm in the Ranks” (reviewed in my previous post, “The Invisible Article”), in more traditional and comic form. But this time they take on a darker, more sinister overtone. Led by a goose-stepping general with a chest full of medals, the army pulls out all the stops to invade the peaceful land. Infantry troops trample fields and threaten with bayonets. Eerie planes highlighted in blacklight photography swoop from the darkened skies. Armored divisions are airlifted by the planes and dropped with oversize umbrellas that serve as parachutes, then roll over everything in sight. Jan and Jannette race one step ahead of the onslaught, but become separated. Most of Janette’s windmill is laid in ruins, while a cake Jan had given her as a gift is crumbled in symbolic fashion beneath the tank treads.

The second half of the film opens in a bomb-damaged church. A tearful Jan prays for his lost love, and for some way that their land can be rid of this enemy. As if in answer to the prayer, a rainstorm breaks out. Jan observes that its coming brings a note of fear to passing troops outside, who run around in panic. Suddenly, some of the soldiers turn orange-red and freeze in their tracks. Jan realizes that the Screwballs have a weakness after all – “Rust!” Armored units find themselves unable to raise their umbrellas in time, and grind to a halt. Lighting bolts pluck the planes out of the skies and send them crashing in flames. The crippled command tank comes to a stop above a muddy puddle – and sinks below the surface without a trace.

The second half of the film opens in a bomb-damaged church. A tearful Jan prays for his lost love, and for some way that their land can be rid of this enemy. As if in answer to the prayer, a rainstorm breaks out. Jan observes that its coming brings a note of fear to passing troops outside, who run around in panic. Suddenly, some of the soldiers turn orange-red and freeze in their tracks. Jan realizes that the Screwballs have a weakness after all – “Rust!” Armored units find themselves unable to raise their umbrellas in time, and grind to a halt. Lighting bolts pluck the planes out of the skies and send them crashing in flames. The crippled command tank comes to a stop above a muddy puddle – and sinks below the surface without a trace.

Come the dawn, the enemy routed, Jan returns to the remains of Jannette’s old mill. The grounds around it are barren and war-beaten. Jan is surprised to find his old concertina still hooked to a mechanism on the side of the mill, where it weakly plays a few notes of music. He looks at Jannette’s front door, and weeps in memory. But to his surprise, the door flies open, and Jannette has returned. The concertina music rises to full volume, and Jan and Jannette dance happily together down the road. As they do, row upon row of tulips spring like magic from the ground, replenishing the landscape to its original splendor. The mill magically rebuilds itself, and the skies fill with a series of clouds appearing to the notes of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, shaped in the pattern of a victory “V”. The title lettering from the opening shot reappears in the skies, but now it reads, “Tulips Shall Always Grow.”

I recall first seeing this film at UCLA years ago, on the big screen from a perfectly preserved 35mm nitrate. The impact was striking – the way the film really deserves to be seen. This moody and moving wartime drama added to the substantial list of Pal’s screen successes in his short period of under a decade producing for Paramount, and gleaned him a nomination for the Academy Award. It’s a shame it didn’t win. But these were the days of tough competition, and with other contenders like Tex Avery’s The Blitz Wolf and the winning Donald Duck, Der Fuhrer’s Face, the academy went for belly-laughs instead of dramatic impact. Pal’s feelings ultimately probably weren’t too badly hurt, as he would achieve further nominations and Oscar gold at subsequent ceremonies. Check out a 35mm transfer on Arnold Leibovit’s fantastic The Puppetoon Movie.

Book Revue (Warner, Daffy Duck, 1/5/46 – Robert Clampett, dir.) includes a one-shot flower appearance. Daffy Duck engages in an extended impression of comedian Danny Kaye, performing a Russian-flavored rendition of Al Jolson’s “Carolina in the Morning”. When he gets to the lyric, “Where the morning glories twine around the door”, a visual shot on such a ‘glory’ is provided, the flower taking on a feminine face and flirting with Daffy, batting her long eyelashes at him.

Book Revue (Warner, Daffy Duck, 1/5/46 – Robert Clampett, dir.) includes a one-shot flower appearance. Daffy Duck engages in an extended impression of comedian Danny Kaye, performing a Russian-flavored rendition of Al Jolson’s “Carolina in the Morning”. When he gets to the lyric, “Where the morning glories twine around the door”, a visual shot on such a ‘glory’ is provided, the flower taking on a feminine face and flirting with Daffy, batting her long eyelashes at him.

The Wacky Weed (Lantz/Universal, Andy Panda, 12/16/46 – Dick Lundy, dir.), abounds in floral gags and punny wordplay. Opening at the Pete Moss Nursery, an effeminate snooty proprietor provides offscreen narration. He tells of the many choices available to the afficionado planning to start a new garden. Choices include the hibiscus – or for cramped quarters, the lowbiscus – or perhaps the “Seabiscus” (playing on the name of the world-famous race horse). But, as the narrator says, that’s a “horse of a different color”. An example of “terrificus oderus” (or stinkweed to you) displays blossoms resembling miniature skunks. “No cocktail party would be complete without the ice plant”, the narrator tells us, displaying a plant with petals resembling ice tongs, and a cube of ice held in each bloom. Gladiolas are introduced as “Glads”, and break into an endless chain of greetings among each other, “Glad to see ya”, “Glad to know ya”, “Glad you’re back”, etc. Andy Panda makes a purchase of an orange flower with a feminine face, but is warned on the way out to “KEEP THE WEEDS AWAY FROM IT!” He takes it home and plants it in the garden, then waters it. The flowers reacts with scubbing motions as if taking a morning shower. But peeping in through a hole in the fence is a scraggly green growth, for which a sign appears in mid-air in Tex Avery fashion, pointing him out as “Nasty ol’ Weed”. The weed burrows its feet into the soil next to the flower, then exerts a stranglehold on her throat. The agonized choking screams of the flower arouse Andy.

The Wacky Weed (Lantz/Universal, Andy Panda, 12/16/46 – Dick Lundy, dir.), abounds in floral gags and punny wordplay. Opening at the Pete Moss Nursery, an effeminate snooty proprietor provides offscreen narration. He tells of the many choices available to the afficionado planning to start a new garden. Choices include the hibiscus – or for cramped quarters, the lowbiscus – or perhaps the “Seabiscus” (playing on the name of the world-famous race horse). But, as the narrator says, that’s a “horse of a different color”. An example of “terrificus oderus” (or stinkweed to you) displays blossoms resembling miniature skunks. “No cocktail party would be complete without the ice plant”, the narrator tells us, displaying a plant with petals resembling ice tongs, and a cube of ice held in each bloom. Gladiolas are introduced as “Glads”, and break into an endless chain of greetings among each other, “Glad to see ya”, “Glad to know ya”, “Glad you’re back”, etc. Andy Panda makes a purchase of an orange flower with a feminine face, but is warned on the way out to “KEEP THE WEEDS AWAY FROM IT!” He takes it home and plants it in the garden, then waters it. The flowers reacts with scubbing motions as if taking a morning shower. But peeping in through a hole in the fence is a scraggly green growth, for which a sign appears in mid-air in Tex Avery fashion, pointing him out as “Nasty ol’ Weed”. The weed burrows its feet into the soil next to the flower, then exerts a stranglehold on her throat. The agonized choking screams of the flower arouse Andy.

Andy tries to extinguish the weed with a Flit can of weed killer – but as the smoke clears, Andy and his flower are out cold, while the weed confidently wears a gas mask. Using smeling salts to revive the flower, he returns to his stranglehold pose. Andy revives and tries to pull the weed out – only below ground, the weed’s roots cling stubbornly around a buried water pipe. Andy tries to dig the weed our with a shovel – but the shovel only gets stuck below the pipe, and the weed tickles Andy’s foot to make him lose his grip and get clunked on the head by the shovel handle. Andy’s had enough, and resorts to the “big guns” by tying a rope around the weed, then fastening the other end to his old car. The weed, however, slips out of the rope, and hooks it over the plumbing fixture of Andy’s sprinkler system. As Andy floors his accelerator, the plumbing begins to uproot itself from the lawn, then reveal pipes heading back to the house, then finally drag the entirety of Andy’s indoor plumbing outdoors – bathtub, sinks, and all. Andy seizes a lawn mower, and pursues the weed across the garden, scalping or severing many objects in two in the process (such as dissecting a fish pond as if he was parting the Red Sea, with the goldfish looking at each other from opposite halves of the water). The weed is cornered at blade point against the garden fence. As Andy threatens to cut him to ribbons, the weed pleads for another chance. Exerting a promise from the weed not to bother his flower anymore, Andy tells the weed and his flower to shake hands. But, once a nasty ol’ weed, always a nasty ol’ weed – once in contact with the flower, the weed reverts to form, and it’s the same old strangle again. Andy takes off after him again with the lawnmower, the weed screaming as his rear end intermittently makes contact with the whirling blades following close behind him.

Daffydilly Daddy (Paramount/Famous, Little Lulu, 5/25/45 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Lulu’s dad, Mr. Moppet, undergoes quite a personality change in this one. Instead of his usual voicing by Jackson Beck as a boisterous, somewhat overbearing basso, he acquires a delicate prissy voice and personality to match, as he engages in his favorite pastime of grooming his newly-developed bloom, “Gedelia”, for a flower show. He applies final pruning in surgical gown and operating-room conditions. Lulu reminds him that the flower show is in 15 minutes. Knowing he hasn’t even had time to shave yet, Mr. Moppet (who should know better by now) entrusts Lulu to get his creation to the flower show, with intent to meet them there. Demonstrating where his priorities lie, he offers a goodbye kiss to his darling before Lulu parts – but gives the kiss to Gedelia instead of Lulu. Lulu and her dog race the flower to the show in a red wagon marked “armored car” – meaning that the flower rides above surrounded by the metal of a trash can. The wagon hits a dead end, and the flower flies out of the trash can, landing squarely in the flower bed of a nearby home. Lulu retrieves it, but is met with a sign warning do not puck the flowers – held by a vicious bulldog.

Daffydilly Daddy (Paramount/Famous, Little Lulu, 5/25/45 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Lulu’s dad, Mr. Moppet, undergoes quite a personality change in this one. Instead of his usual voicing by Jackson Beck as a boisterous, somewhat overbearing basso, he acquires a delicate prissy voice and personality to match, as he engages in his favorite pastime of grooming his newly-developed bloom, “Gedelia”, for a flower show. He applies final pruning in surgical gown and operating-room conditions. Lulu reminds him that the flower show is in 15 minutes. Knowing he hasn’t even had time to shave yet, Mr. Moppet (who should know better by now) entrusts Lulu to get his creation to the flower show, with intent to meet them there. Demonstrating where his priorities lie, he offers a goodbye kiss to his darling before Lulu parts – but gives the kiss to Gedelia instead of Lulu. Lulu and her dog race the flower to the show in a red wagon marked “armored car” – meaning that the flower rides above surrounded by the metal of a trash can. The wagon hits a dead end, and the flower flies out of the trash can, landing squarely in the flower bed of a nearby home. Lulu retrieves it, but is met with a sign warning do not puck the flowers – held by a vicious bulldog.

Lulu and her dog spend most of the picture devising distractions to occupy the bulldog while they attempt to steal back the flower from under his nose – including at least two sequences loosely reworked from Lulu’s premiere episode, Eggs Don’t Bounce (1943), with her dog impossibly on both ends of activity tossing tambourines to himself from opposite sides of the front gate, and Lulu resorting to blatantly sterotypical blackface disguise as the mansion’s new maid. Finally reaching the flower show one step ahead of Papa, Lulu and her dog stand by as an honor guard to Gedelia. But a hummingbird noses in on the blossoms, and Lulu takes aim at him with her trusty slingshot. The rock misses the bird – but severs the bloom off Gedelia. Having her dog pull Daddy’s top hat down over his eyes to buy time. Lulu grabs a comparable white flower, and dips it in blue paint to match Gedelia’s color, then disposes of the remains of Gedelia in a barrel of nearby plant food. Papa attempts to give Gedelia another affectionate kiss – and gets his hands and face covered in blue paint. As he is about to give Lulu the verbal chewing-out of a lifetime, the barrel of plant food rumbles, and out pops a new Gedelia, now four times its original size. Mr. Moppet wins first prize. However, as the prize is presented, the hummingbird returns. Lulu takes aim again with the slingshot, and before Daddy can stop her, Gedelia is rendered nothing more than a pile of giant petals, with Lulu and her dog looking out at the audience from under the petal pile for the iris out.

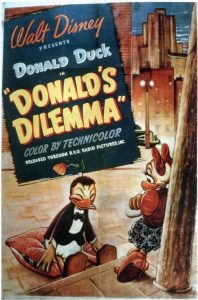

Donald’s Dilemma (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 7/11/47 – Jack King, dir.). The misnomer title (which really should have been “Daisy’s Dilemma”) is a starring vehicle for Daisy Duck, voiced by Gloria Blondell (Joan Blondell’s sister, and remembered as Peg on TV’s “The Life of Riley”). But the exhibitors probably felt Donald’s name was a better drawing-card for the movie posters. Notably, it was written by Roy Williams (the “Big Mooseketeer” of the Mickey Mouse Club), and is probably one of his most moody and unique scripts.

Donald’s Dilemma (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 7/11/47 – Jack King, dir.). The misnomer title (which really should have been “Daisy’s Dilemma”) is a starring vehicle for Daisy Duck, voiced by Gloria Blondell (Joan Blondell’s sister, and remembered as Peg on TV’s “The Life of Riley”). But the exhibitors probably felt Donald’s name was a better drawing-card for the movie posters. Notably, it was written by Roy Williams (the “Big Mooseketeer” of the Mickey Mouse Club), and is probably one of his most moody and unique scripts.

The film is the second act in a sort of trilogy where director Jack King decides to play games and take a hiatus from use of Donald’s usual difficult-to-understand quacking, by providing him with impossibly clear and distinct vocal powers. The first such outing was “Donald’s Double Trouble” (1946), where Donald meets his physical duplicate, but possessing the voice, charm and personality of Ronald Coleman. Donald uses this newcomer to try to patch up his love life with Daisy – until the double can’t resist trying to take over for himself. In the third voice-switch adventure, “Donald’s Dream Voice” (1948). Donald acquires the same Ronald Coleman voice by meas of a box of Ajax Voice Pills, but has to track all over town the last pill which he was saving to propose to Daisy. Jack Kinney would even reunite the Duck with the Coleman voice one more time in “Donald’s Diary’ (1954) as the unexplained “consciousness” voice of the entries in his diary.

The unusual plot uses a potted flower as the central impetus. Opening in a psychiatrist’s office, Daisy tells the story of her plight. On a routine walk through the city with Daisy, Donald is hit on the head by a heavy flower pot toppling from a skyscraper ledge. The impact causes him to hear voices in his head, telling him that he is the world’s greatest singer. He gets up, brushes himself off, and breaks into a crooning rendition of “When You Wish Upon a Star”, sounding as close as the Disney voice artists could get to the style of Frank Sinatra. Daisy is enthralled – until she realizes Donald doesn’t know her anymore. Donald is scooped up by an extended cane out of the office window of a talent agent, and disappears. Daisy can’t find him – until his voice appears on the radio, on records, his picture in magazines and trade publications, and he becomes an overnight star. Daisy keeps the flower from the incident as a remembrance of him over her mantel. But loss of Donald makes her unable to sleep, and drives her into near insanity (pictured by often censored images of her with a hangman’s noose, a bottle of poison, and a revolver pointed at her head, and about to savagely chew her own arm off). Newspaper announcement of Donald’s first public appearance draws her to Radio City theatre – but she is left on the outside looking in behind a sellout crowd.

The unusual plot uses a potted flower as the central impetus. Opening in a psychiatrist’s office, Daisy tells the story of her plight. On a routine walk through the city with Daisy, Donald is hit on the head by a heavy flower pot toppling from a skyscraper ledge. The impact causes him to hear voices in his head, telling him that he is the world’s greatest singer. He gets up, brushes himself off, and breaks into a crooning rendition of “When You Wish Upon a Star”, sounding as close as the Disney voice artists could get to the style of Frank Sinatra. Daisy is enthralled – until she realizes Donald doesn’t know her anymore. Donald is scooped up by an extended cane out of the office window of a talent agent, and disappears. Daisy can’t find him – until his voice appears on the radio, on records, his picture in magazines and trade publications, and he becomes an overnight star. Daisy keeps the flower from the incident as a remembrance of him over her mantel. But loss of Donald makes her unable to sleep, and drives her into near insanity (pictured by often censored images of her with a hangman’s noose, a bottle of poison, and a revolver pointed at her head, and about to savagely chew her own arm off). Newspaper announcement of Donald’s first public appearance draws her to Radio City theatre – but she is left on the outside looking in behind a sellout crowd.

Efforts to sneak in the stage door are either blocked by throngs of autograph hunters, or by the theatre night watchman. Finally encountering Donald by happenstance on the street, she pleads that she’s starving for his love – which Donald, still not knowing her, interprets as a pitch for charity, causing him to toss Daisy a dime. Back in the present, Daisy asks the psychiatrist for his professional advice. “I can help you”, the doctor says, “but first you have a big decision to make. Do want the world to have him and his beautiful golden voice, or do you want him back again for yourself? It’s either the world or you.” Without a second of hesitation, Daisy reverts to Donald’s temperament, smashing a globe in the doctor’s office and shouting, “Me! Me! MEEEEEEEEE!!!” The somewhat anticlimactic ending has Daisy instructed to use the same flower to restore Donald with another blow. Running out of alotted film time, Daisy conveniently finds the theatre night watchman asleep at the stage door, and tiptoes in on Donald’s performance. Climbing to the highest theatre rafters, she drops the pot on Donald. Immediately upon impact (and heard for the firsy time in the entire film), we hear the non-melodious quacking of Donald as we know him – who is ousted from the stage buy an angry populace, and booted out the stage door, where Daisy has placed a pillow at measured distance to break his fall. “Daisy, where have you been?”, a happy Donald shouts, and smothers her with kisses for the iris out.

The best florists usually guarantee that their blooms will last at least a week after delivery. I guarantee more blossoms for at least twice that long, which will be revealed in subsequent weeks. Till then, don’t go to seed, and come back for more fragrant delights next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin. And yet I say unto you, that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.” — Matthew 6:28-29

Of this week’s selection of prize blooms under consideration, I would have to “pick” as my favourite “Dance of the Weed”; Scott Bradley’s Waltz of the Flowers may not be as catchy as Tchaikovsky’s, but it’s a great deal more sophisticated. However, there’s some really arcane stuff going on in “Daffy Dilly Daddy”.

“Gedelia” is a variant spelling of the Hebrew name Gedaliah. Tzom Gedaliah, the fast of Gedaliah, falls two days after Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year, and like most fast days in the Hebrew calendar commemorates the destruction of the Temple of Solomon. Gedaliah, appointed governor of the Babylonian province of Judea by King Nebuchadnezzar, was assassinated by an agent of the king of Ammon, thereby ending Jewish self-rule for the next 2500 years.

Gedelia the flower is clearly a ball dahlia, with a single spherical bloom on the end of a leafy stem. “Dahlia” rhymes with “Gedaliah”, and would have been a terribly clever pun; I can only guess that the variant “Gedelia” was used because it sounds more feminine (and can in fact be a woman’s name). Dahlias are dioecious, having separate male and female flowers, and Lulu’s dad refers to Gedelia as “her”.

However, she is BLUE; and as every dahlia breeder knows, the hundreds of varieties of dahlia come in every shade of every colour EXCEPT blue. It’s just not in the genome. Since the 1800s the Royal Botanical Society of Edinburgh has offered a prize, in the thousands of pounds, for breeding a blue dahlia; it remains unclaimed. Shades of mauve, purple and lilac are as close as anyone has ever got.

No wonder Lulu’s dad is so obsessively protective of his beloved Gedelia. That flower would be worth a fortune!

Perhaps only coinicidentally, by the time “Daffy Dilly Daddy” was released, Paramount had already begun production of “The Blue Dahlia”, a film noir starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake with an original screenplay by Raymond Chandler. But the Blue Dahlia of the title is a nightclub, not a flower.

You really can learn a lot of things from the flowers — and I’m looking forward to next week’s bouquet!

“Donald’s Dilemma” is a really good example of how talented some of Disneys animators were. The level of character acting in that cartoon is astounding.

“Tulips Shall Grow” is also fascinating to me in that many of its scenes seem to anticipate similar setups in George Pal’s “War of the Worlds:” The eerie red lighting during the invasion, the praying in a wrecked church when all seems lost, the slow-motion crashing as the war-machines succumb to “Rust”, just as the Martian war-machines did when the virus took effect.

You seem to have forgotten to mention the Nutcracker Suite segment of Fantasia, with its dancing blossoms, Cossack thistles, dainty milkweed seed ballerinas, and most memorable of all, the Chinese dancing mushrooms.

The Wacky Weed must be one of the only post-Code studio cartoons to display a toilet (even if partially obscured).

Thanks Charles, for your many interesting posts. And by the way it’s Ronald COLMAN, not COLEMAN. Just for future reference.

Are you going to look at Disney’s Robin Hood with fox Robin & Marian walking through Sherwood Forest to the Oscar-nominated song ‘Love’?

A beautiful floral cartoon from this era is “A Day in June” (Fox/Terrytoons, 3/3/44 — Eddie Donnelly, dir.), an animated setting of the famous poem by James Russell Lowell (“And what is so rare as….?”). It’s a pastoral idyll in the same vein as the Silly Symphonies of ten years earlier; as expected, Terry falls short of the standard set by Disney, but surprisingly, not by all that much. The flowers and trees, and the birds and the bees, are beautifully rendered; some of the floral backgrounds are absolutely breathtaking. Best of all, it has perhaps the most beautiful musical score that Philip Scheib ever composed for a cartoon, scored for a traditional orchestra with strings, oboe, English horn, bassoon, and a very prominent harp obbligato — but not a single saxophone! Hooray!

The narrator recites the Lowell poem, which more or less determines the action of the cartoon. Two kinds of flower are mentioned in consecutive lines: “The cowslip startles in meadows green, / The buttercup catches the sun in its chalice.” However, at this moment in the cartoon, we see a field of, not cowslips or buttercups, but tulips! Besides — and this is Lowell’s mistake, not Terry’s — cowslips only bloom in the early spring; it really would be a rare day in June if you were to see one then!