As 1941 progressed, it seemed that America’s worst-kept secret was the possibility of involvement – or even invasion – from the conflicts in Europe and elsewhere. The draft was in full swing, and Americans had to be suspicious of where all that manpower was ultimately heading. Those that believed that its presence alone would be a sheer deterrent to any invader may have been like ostriches burying their head in the sand. By year’s end came the bombshell – in literal terms, which your grade school history training should have made any reader well familiar with. A drastic change in mood and atmosphere of animation would follow – though it is evident in hindsight that productions immediately preceding the outbreak of war were not by any means naive of what the future might have in store, already familiarizing the viewing public with many of the sights and situations which would become commonplace in a later war-torn society.

After rushing to the screen a hasty salute to the Army in “Recruiting Daze”, reviewed last week, it was time for equal-time for the Navy at Lantz studios. Salt Water Daffy (Universal, 6/9/41 – Walter Lantz. dir.) is the companion spot-gag piece, following the fleet on a day’s maneuvers. It features two gags involving aircraft. A small reconnaissance plane takes off from the deck of a ship – but it seems more than one set of eyes are needed for this mission. So the plane carries a tow rope fastened to its tail. As it takes off, it lugs behind the entire battleship it is tied to, the ship rising at the same 45 degree angle as the plane. In a second gag, anti-aircraft target practice is demonstrated. There is no live ammo – instead, an arcade-style screen is fastened on the end of an extension pole just over the side of the ship, depicting a toy plane flying over the horizon, and keeping automatic score when the gunner aims right. While I’m sure some arcade machine must have achieved such a visual by mechanical means, the depiction in the cartoon seems amazingly up to date, as if video games existed in 1941!

Aviation Vacation (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 8/2/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.), is one of the weaker Avery travelogue or spot-gag cartoons, with gags feeling much more random and disconnected than usual, and some material derivative or seeming left over from other films, particularly the ending. Avoiding discussion of the travelogue gags, some of which have been covered in previous articles, the flying sequences are as follows. A flight controller doesn’t know if he’s at an airport or at Santa Anita, announcing on the loudspeaker, “Visibility, clear. Track, fast.” Takeoff is of the old flapping-wings variety. Weather is not what the airport announcer advertised. While a narrator comments that the sun is always shining in sunny California, it is visible only within a small square opening in the sky, surrounded by torrential rain storms. The plane proceeds ahead, bobbing along to the tune of “April Showers”. Paralleling the gag from “Ceiling Hero”, Avery has his plane follow the path of a railroad track instead og a road below. The plane’s shadow approaches a tunnel – and folds in its wings to dart clear through it, disappearing from view for the length of the tunnel, then also dodges a fast freight heading in the opposite direction when it emerges. During the night, the moon dodges out of the way of the passing plane. Next morning, the plane passes its sister ship returning from the Orient. The two planes pass so close, the view out the window is directly into the windows of the other plane, much like the passing of two railway cars. The plane engages in various musical bobbing between sequences, including swaying to “Aloha Oe” when it is time to head home. Reprising the ending setup from “Land of the Midnight Fun”, a dense fog blankets the plane’s home base, and a control tower voice instructs the plane to circle the field. With only the cabin lights of the plane visible, we see the plane engage in several circular revolutions, then the fog suddenly clears. We find the plane has somehow become attached to the cables of a carnival airplane ride in an amusement park, and continues in its tethered round-and-round flight, ad infinitum.

Aviation Vacation (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 8/2/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.), is one of the weaker Avery travelogue or spot-gag cartoons, with gags feeling much more random and disconnected than usual, and some material derivative or seeming left over from other films, particularly the ending. Avoiding discussion of the travelogue gags, some of which have been covered in previous articles, the flying sequences are as follows. A flight controller doesn’t know if he’s at an airport or at Santa Anita, announcing on the loudspeaker, “Visibility, clear. Track, fast.” Takeoff is of the old flapping-wings variety. Weather is not what the airport announcer advertised. While a narrator comments that the sun is always shining in sunny California, it is visible only within a small square opening in the sky, surrounded by torrential rain storms. The plane proceeds ahead, bobbing along to the tune of “April Showers”. Paralleling the gag from “Ceiling Hero”, Avery has his plane follow the path of a railroad track instead og a road below. The plane’s shadow approaches a tunnel – and folds in its wings to dart clear through it, disappearing from view for the length of the tunnel, then also dodges a fast freight heading in the opposite direction when it emerges. During the night, the moon dodges out of the way of the passing plane. Next morning, the plane passes its sister ship returning from the Orient. The two planes pass so close, the view out the window is directly into the windows of the other plane, much like the passing of two railway cars. The plane engages in various musical bobbing between sequences, including swaying to “Aloha Oe” when it is time to head home. Reprising the ending setup from “Land of the Midnight Fun”, a dense fog blankets the plane’s home base, and a control tower voice instructs the plane to circle the field. With only the cabin lights of the plane visible, we see the plane engage in several circular revolutions, then the fog suddenly clears. We find the plane has somehow become attached to the cables of a carnival airplane ride in an amusement park, and continues in its tethered round-and-round flight, ad infinitum.

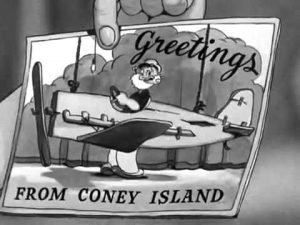

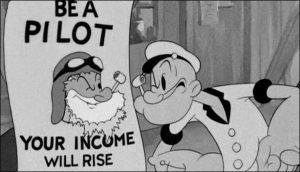

Pest Pilot (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 8/8/41 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Tendlar/Tom Baron, anim.) – Popeye tries a new career, presiding over an “air-conditioned airport” (with a motto sign reading “Airplanes is the safest things on Earth”) as senior pilot. Did I say senior? Well one would-be pilot may not best him in flight hours logged, but certainly exceeds him in years of existence – Poopdeck Pappy. As Popeye hand-whittles a perfect propeller out of a raw board at lightning speed, then bends the propeller shaft with his bare hands into a U-curve to hold it in place, Poopdeck appears at Popeye’s door, imitating the sounds of an aircraft engine. “Ahoy, son”, he asks, “Need a good pilot?” “Nope. Got one”, replies Popeye, referring to himself. Pappy holds up a poster reading “Be a pilot and your income will rise sky high”, and pokes his head through the paper in place of the pilot’s face depicted. “I’m just the type”, he insists. Popeye responds, “You’re not quite young enough yet to fly – but you’re old enough to read!” He points to another poster on the wall: “All prospective pilots must be young, strong, and healthy, see well, and look good.” “That’s me all over”, boasts Pappy, pulling up his shirt, to briefly expand his rickety chest, which looks like the torso of the nursery-rhyme “crooked man”. Popeye delivers a strike three to Pappy’s arguments – “Ya don’t know how ta fly.” Pappy states he does so, and can prove it. He produces two photos from his wallet. One depicts him at grade school age, with caption, “Little Poopdeck, kite flying champion of Public School No. 61″, while the second shows him in a photography studio behind a fake backdrop of a cardboard plane, captioned, “Greetings from Coney Island”.

Pest Pilot (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 8/8/41 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Tendlar/Tom Baron, anim.) – Popeye tries a new career, presiding over an “air-conditioned airport” (with a motto sign reading “Airplanes is the safest things on Earth”) as senior pilot. Did I say senior? Well one would-be pilot may not best him in flight hours logged, but certainly exceeds him in years of existence – Poopdeck Pappy. As Popeye hand-whittles a perfect propeller out of a raw board at lightning speed, then bends the propeller shaft with his bare hands into a U-curve to hold it in place, Poopdeck appears at Popeye’s door, imitating the sounds of an aircraft engine. “Ahoy, son”, he asks, “Need a good pilot?” “Nope. Got one”, replies Popeye, referring to himself. Pappy holds up a poster reading “Be a pilot and your income will rise sky high”, and pokes his head through the paper in place of the pilot’s face depicted. “I’m just the type”, he insists. Popeye responds, “You’re not quite young enough yet to fly – but you’re old enough to read!” He points to another poster on the wall: “All prospective pilots must be young, strong, and healthy, see well, and look good.” “That’s me all over”, boasts Pappy, pulling up his shirt, to briefly expand his rickety chest, which looks like the torso of the nursery-rhyme “crooked man”. Popeye delivers a strike three to Pappy’s arguments – “Ya don’t know how ta fly.” Pappy states he does so, and can prove it. He produces two photos from his wallet. One depicts him at grade school age, with caption, “Little Poopdeck, kite flying champion of Public School No. 61″, while the second shows him in a photography studio behind a fake backdrop of a cardboard plane, captioned, “Greetings from Coney Island”.

Popeye laughs heartily, and calls Pappy nothing but a “picture postcard pilot”. Pappy keeps insisting that Popeye “give this old barnacle-scrapin’ seadog a chance”, but Popeye eventually gets tough, threatening “I’ll make ‘ya FLY1″ He lunges at Pappy, causing him to retreat out the hangar door, while Popeye nails up signs reading “Scram”, “Go home”, “Beat it”, “No trespassing, “This means you”, etc. “I can take a hint”, mutters Pappy. But outside rests a pane which is unattended. Pappy, seeing opportunity to prove he has the stuff, tries to spin the prop, bur can’t get the engine to kick over. About to give up, he gives the propeller blade a backwards kick before departing. The kick is a lucky blow, and the plane starts up. Pappy jumps into the cockpit, looks around until he finds the control stick, pulls back, and is away. He ascends in a zoom past a house, so fast that the force of his passing rips away the walls, reducing the structure to its wooden framework. He zips through a cloud, leaving a watery hole of his silhouette. A dissolve transports us to another location, where passengers stampede as a mob out the exit of an underground subway, followed by Pappy and his plane in pursuit. Another dissolve finds us at a tropical island, where Pappy’s plane skims over the tops of palm trees, giving their fronds a “butch”: haircut. Another dissolve, and we are on the Arctic, where the exhaust of the passing plane melts two Eskimos out of their igloo house and home. Yet another dissolve, and we are back at Popeye’s airport, with the plane performing wild loops just outside the hangar, then heading straight up, with Poopdeck hanging from the tail. Pappy looks down, and sees the entire planet falling farther and farther away. He struggles to climb up the length of the fuselage, and just reaches the control stick, forcing it forward. Now the plane reverses course, heading straight down, and tossing Pappy into the cockpit. The view of the Earth is reversed, looming closer and closer. Pappy seeks in vain any control or lever on the dashboard that might help him, and opens a hatch with a telephone inside. Pappy speaks frantically into the receiver: “Hello! Hello! How d’ya anchor this doggone sloop?” A telephone operator replies, “Sorry, sir. We can’t give you that information.”

Popeye laughs heartily, and calls Pappy nothing but a “picture postcard pilot”. Pappy keeps insisting that Popeye “give this old barnacle-scrapin’ seadog a chance”, but Popeye eventually gets tough, threatening “I’ll make ‘ya FLY1″ He lunges at Pappy, causing him to retreat out the hangar door, while Popeye nails up signs reading “Scram”, “Go home”, “Beat it”, “No trespassing, “This means you”, etc. “I can take a hint”, mutters Pappy. But outside rests a pane which is unattended. Pappy, seeing opportunity to prove he has the stuff, tries to spin the prop, bur can’t get the engine to kick over. About to give up, he gives the propeller blade a backwards kick before departing. The kick is a lucky blow, and the plane starts up. Pappy jumps into the cockpit, looks around until he finds the control stick, pulls back, and is away. He ascends in a zoom past a house, so fast that the force of his passing rips away the walls, reducing the structure to its wooden framework. He zips through a cloud, leaving a watery hole of his silhouette. A dissolve transports us to another location, where passengers stampede as a mob out the exit of an underground subway, followed by Pappy and his plane in pursuit. Another dissolve finds us at a tropical island, where Pappy’s plane skims over the tops of palm trees, giving their fronds a “butch”: haircut. Another dissolve, and we are on the Arctic, where the exhaust of the passing plane melts two Eskimos out of their igloo house and home. Yet another dissolve, and we are back at Popeye’s airport, with the plane performing wild loops just outside the hangar, then heading straight up, with Poopdeck hanging from the tail. Pappy looks down, and sees the entire planet falling farther and farther away. He struggles to climb up the length of the fuselage, and just reaches the control stick, forcing it forward. Now the plane reverses course, heading straight down, and tossing Pappy into the cockpit. The view of the Earth is reversed, looming closer and closer. Pappy seeks in vain any control or lever on the dashboard that might help him, and opens a hatch with a telephone inside. Pappy speaks frantically into the receiver: “Hello! Hello! How d’ya anchor this doggone sloop?” A telephone operator replies, “Sorry, sir. We can’t give you that information.”

Back at the hangar, Popeye, suiting up for a flight in the locker rom, hears an announcement over the airport P.A. system. “Whiskery old man in runaway plane is about to crash.” The microphone of the announcer remains live, as we hear the whistling descent of the plane, and a loud crash that shakes the rafters of the building. The announcer concludes, “That is all.” “That can’t be Pappy”, mutters Popeye, dismissing the importance of the announcement. “Oh, yes it can”, responds the all-knowing announcer. Popeye shouts in terror, “Me Pappy!”, and darts through the locker room door without bothering to open it. Outside, he finds the wreckage, and searches in vain for what has become of his Pop. But a call of “Ahoy” from far above reveals Pappy, safe and sound, hanging by his shirt from a water tower. The tower collapses, but Popeye catches the old sailor before the structure can crash down around him. Learning that Pappy is all right, Popeye’s sympathetic mood changes to anger again, and he orders Pappy to get out. Pappy trudges away, whimpering that he only wanted to be “an ace pilot like you”. Popeye feels complimented, and takes pity on the old coot, placing a pilot’s hat and wing medal upon his Pop, and telling him he can be a pilot after all. But a pilot of what? A large lawn mower, used for trimming the runway. But Pappy is satisfied, and mans his driver’s seat with all the poise of a movie pilot, for the iris out.

Back at the hangar, Popeye, suiting up for a flight in the locker rom, hears an announcement over the airport P.A. system. “Whiskery old man in runaway plane is about to crash.” The microphone of the announcer remains live, as we hear the whistling descent of the plane, and a loud crash that shakes the rafters of the building. The announcer concludes, “That is all.” “That can’t be Pappy”, mutters Popeye, dismissing the importance of the announcement. “Oh, yes it can”, responds the all-knowing announcer. Popeye shouts in terror, “Me Pappy!”, and darts through the locker room door without bothering to open it. Outside, he finds the wreckage, and searches in vain for what has become of his Pop. But a call of “Ahoy” from far above reveals Pappy, safe and sound, hanging by his shirt from a water tower. The tower collapses, but Popeye catches the old sailor before the structure can crash down around him. Learning that Pappy is all right, Popeye’s sympathetic mood changes to anger again, and he orders Pappy to get out. Pappy trudges away, whimpering that he only wanted to be “an ace pilot like you”. Popeye feels complimented, and takes pity on the old coot, placing a pilot’s hat and wing medal upon his Pop, and telling him he can be a pilot after all. But a pilot of what? A large lawn mower, used for trimming the runway. But Pappy is satisfied, and mans his driver’s seat with all the poise of a movie pilot, for the iris out.

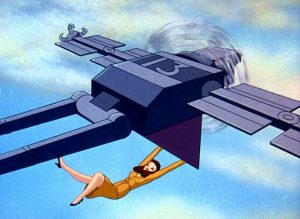

Barely worth a mention for purposes of this article is Max Fleischer’s Superman (Paramount, 9/26/41, Dave Fleischer, dir., Steve Muffati/Frank Endres, anim.), in which Lois Lane wins her wings by proving she can pilot a small plane for a couple of shots to a mad scientist’s lair. One might also question whether to reference the follow-up, The Mechanical Monsters (11/28/41, Dave Fleischer, dir., Steve Muffati/George Germanetti, anim.), in which giant robots transform into flying machines by wing flaps extending ftom their arms, and a propeller ring around their necks.

Barely worth a mention for purposes of this article is Max Fleischer’s Superman (Paramount, 9/26/41, Dave Fleischer, dir., Steve Muffati/Frank Endres, anim.), in which Lois Lane wins her wings by proving she can pilot a small plane for a couple of shots to a mad scientist’s lair. One might also question whether to reference the follow-up, The Mechanical Monsters (11/28/41, Dave Fleischer, dir., Steve Muffati/George Germanetti, anim.), in which giant robots transform into flying machines by wing flaps extending ftom their arms, and a propeller ring around their necks.

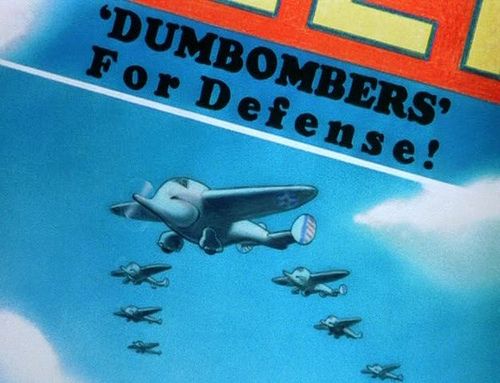

Despite Disney’s usual insistence upon avoiding topical gags to make his films appear “timeless”, his staff couldn’t resist including one in the production of Dumbo (Disney/RKO, 10/22/41) which, while not specifying any specific conflict so that it might pass under any military conditions, depicts a magazine’s feature story on the air force’s answer to Dumbo’s success as the world’s only flying elephant (if we don’t count all those ones at Terrytoons’ gasoline filling stations). Their newest secret weapon – bombing planes, with the nose of each fashioned in the shape of Dumbo’s head – with the caption, “Dumbobombers for defense!”

Rookie Revue (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 10/25/41 – I (Friz) Freleng, dir.), provides our third spot-gag film of the day. Warner’s day with the Army includes a sequence showing how early conscriptees were trained before real equipment was readily available. Gunners practiced machine gun fire with a wooden two-by-four straddled over the top of a sawhorse, while another gunner practices pistol shots in the manner of a three year old child, pointing his bare finger and saying “Bang”. Tank corps are trained with any old jalopy, taxi, or good humor truck, bearing a paper label reading “Tank”. The most impractical substitution is made, however, by the parachute corps, which sends a sky trooper jumping out the door of a real plane in flight. He pulls his ripcord, only to have another paper sign emerge, reading, “Parachute”, as he falls helplessly to his oblivion. A second aviation gag has two pursuit planes engage in “aerial games”.- as they draw in skywriting contrails a double pair of intersecting crosses in the sky, then skywrite “X”s and “O”s for a game of tic-tac-toe.

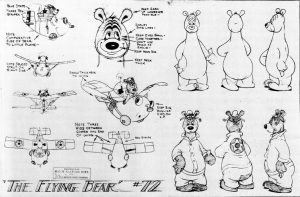

The Flying Bear (MGM, Barney Bear, 11/1/41 – Robert Allen/Rudolf Ising, dir.) – At a U.S. Army air base, we find loveable lummox Barney Bear, working away in the repair shop as a mechanic. The subject of his efforts is the smallest plane on the base, a little pipsqueak which is barely larger than the wheels of the other planes, which Barney appears to have adopted as his own “pet” project for restoration. The coloration on the little plane gives some indication of its age, bearing markings and colors of planes in use by the air corps since the early 1930’s (an olive green fuselage, yellow wings and tail, and red, white and blue stripes on the rudder resembling the American flag, as well as red, white and blue star insignia on the wings). In contrast, all the other planes on the field are predominantly unpainted and silver in color, as was the norm for modern trainers of the day. With the exception of a miniature pusher-prop engine attached above the wing, Barney’s diminutive plane bears strong resemblance to a plane actually used by the air corps during the 1930’s and into the early ‘40’s, which was the smallest plane accepted for a government production-line contract – the Boeing P-26, affectionately known as the “Peashooter”. Designed as a compact fighter, the plane over the years became outclassed in speed by newer, larger models, and as space capacity for larger makes expanded in several applications such as use aboard naval vessels, the plane fell out of favor, and saw little use when serious war broke out. It may have been this “forgotten man” quality that caused Rudolf Ising to sentimentally devote this episode to the “little guy in a big world” theme, providing a built-in personality for the little plane, and a wonderful opportunity for elaborate and meticulous character animation.

Barney’s first chore is to get the engine running on his little “friend”. He accomplishes this by mixing a strange “cocktail” in a pair of pails, consisting of motor oil, gasoline, and every stray nut, bolt, screw, or gear he has hanging around the hangar. He is also a conscientious bartender, ensuring conditions are sanitary by fishing out a fly from the caustic mess before shaking well, then pouring the concoction into the engine chamber. With a bit of a burp and a hiccup, the little plane pops to life. We now see why Ising redesigned the plane with an above-wing pusher engine – such move allowing the nose of the plane to be animated in freeform, with headlights that become eyes, engine crank instead of a propeller shaft to serve as a nose, and a mouth drawn around the lower front of the fuselage. The plane turns out to be affectionate and eager to please, almost in the manner of a puppy dog seeking approval from his master. As we will see, however, its obedience level has a limit, and a streak of personal pride tends to arouse its anger at inopportune times – a sure-fire recipe for developing trouble.

Barney’s first chore is to get the engine running on his little “friend”. He accomplishes this by mixing a strange “cocktail” in a pair of pails, consisting of motor oil, gasoline, and every stray nut, bolt, screw, or gear he has hanging around the hangar. He is also a conscientious bartender, ensuring conditions are sanitary by fishing out a fly from the caustic mess before shaking well, then pouring the concoction into the engine chamber. With a bit of a burp and a hiccup, the little plane pops to life. We now see why Ising redesigned the plane with an above-wing pusher engine – such move allowing the nose of the plane to be animated in freeform, with headlights that become eyes, engine crank instead of a propeller shaft to serve as a nose, and a mouth drawn around the lower front of the fuselage. The plane turns out to be affectionate and eager to please, almost in the manner of a puppy dog seeking approval from his master. As we will see, however, its obedience level has a limit, and a streak of personal pride tends to arouse its anger at inopportune times – a sure-fire recipe for developing trouble.

Barney seats himself in the cockpit, as the plane happily wags its “tail” and exchanges periodic conspiratorial eyewinks with Barney to prove they are pals, on the same side of the fence against the big old disparaging world. The plane put-puts its way out of the hangar, with Barney giving automobile-style hand signals to make a right turn past another plane’s massive wheels. As they pass it, the larger plane emits a brief belch of black exhaust at them from its tail pipe. The small plane is offended, and kicks with its wheels at the runway surface, as a dog would truing to bury the smell of its daily duties, then flips up its tail disdainfully. Another belch of black exhaust from the big plane ends the confrontation, Barney and the little plane deciding its time to just continue on their way. Taxiing out to the main runway, Barney’s plane revs up its engine, and begins to roll along at increasing speed in preparation for takeoff. Suddenly, its advancement is stopped cold, as the roar of an approaching motor sends Barney and the plane into a cowering huddle under the protection of the plane’s wings, and four large training planes barely miss them, coming in for a landing on the same runway. When the coast is finally clear, the little plane tries again, adding a little gallop with its tires to get Barney and itself airborne. The plane begins to soar gracefully, but only for a moment, as another fighter takes off from behind them and overtakes them in speed, narrowly buzzing underneath the little plane’s belly as it passes. The little plane’s temper is rising and it is on the verge of doing something about it, when a bigger hazard suddenly removes all thought of retaliation for the first humiliation. With reaction of shock, the little plane finds it is being pursued, by the largest plane on the base – and perhaps in the whole air force – a giant behemoth bomber, bristling with machine guns and cannon, labeled “Flying Fortress”. This was again a reference to a real-life plane, the recognized nickname of the Boeing B-17 heavy bomber. (Interesting that the same aircraft company would have a reputation for both the Army’s smallest plane and for one of its largest.) Barney is briefly ejected from the cockpit at the giant bomber sends the little plane into a series of flips, yet returns to his plane through sheer will and frantic clawing at air. The plane’s temper is really being tested, and it raises its wheels in the manner of the gloved hands of a boxer, putting up its dukes. But Barney, playing the arbiter of all squabbles, taps the plane on the “head” and wig-wags a cautioning finger of disapproval at the little plane’s combative attitude. Not wanting to displease its master, the little plane backs down, and resumes its original smile.

Barney seats himself in the cockpit, as the plane happily wags its “tail” and exchanges periodic conspiratorial eyewinks with Barney to prove they are pals, on the same side of the fence against the big old disparaging world. The plane put-puts its way out of the hangar, with Barney giving automobile-style hand signals to make a right turn past another plane’s massive wheels. As they pass it, the larger plane emits a brief belch of black exhaust at them from its tail pipe. The small plane is offended, and kicks with its wheels at the runway surface, as a dog would truing to bury the smell of its daily duties, then flips up its tail disdainfully. Another belch of black exhaust from the big plane ends the confrontation, Barney and the little plane deciding its time to just continue on their way. Taxiing out to the main runway, Barney’s plane revs up its engine, and begins to roll along at increasing speed in preparation for takeoff. Suddenly, its advancement is stopped cold, as the roar of an approaching motor sends Barney and the plane into a cowering huddle under the protection of the plane’s wings, and four large training planes barely miss them, coming in for a landing on the same runway. When the coast is finally clear, the little plane tries again, adding a little gallop with its tires to get Barney and itself airborne. The plane begins to soar gracefully, but only for a moment, as another fighter takes off from behind them and overtakes them in speed, narrowly buzzing underneath the little plane’s belly as it passes. The little plane’s temper is rising and it is on the verge of doing something about it, when a bigger hazard suddenly removes all thought of retaliation for the first humiliation. With reaction of shock, the little plane finds it is being pursued, by the largest plane on the base – and perhaps in the whole air force – a giant behemoth bomber, bristling with machine guns and cannon, labeled “Flying Fortress”. This was again a reference to a real-life plane, the recognized nickname of the Boeing B-17 heavy bomber. (Interesting that the same aircraft company would have a reputation for both the Army’s smallest plane and for one of its largest.) Barney is briefly ejected from the cockpit at the giant bomber sends the little plane into a series of flips, yet returns to his plane through sheer will and frantic clawing at air. The plane’s temper is really being tested, and it raises its wheels in the manner of the gloved hands of a boxer, putting up its dukes. But Barney, playing the arbiter of all squabbles, taps the plane on the “head” and wig-wags a cautioning finger of disapproval at the little plane’s combative attitude. Not wanting to displease its master, the little plane backs down, and resumes its original smile.

Now, the plane settles into some graceful aerial acrobatics, bobbing in waltz tempo to strains of “The Man on the Flying Trapeze”, tiptoeing over clouds and performing spins atop them on its wingtip. A close shot on Barney’s face depicts a look that can only be described as believing he is in 7th Heaven. But the playful plane is still looking for a little excitement – and spots it in the form of a slow-flying pelican. While Barney isn’t paying notice, the plane creeps up behind the pelican, then startles it with a honk of its horn to make way. The frightened bird dodges upward, as the little plane proceeds ahead, taking the bird’s place in the sky lanes. The pelican also has a temper, and is miffed at being passed. It speeds up, zips under the plane’s belly, and bucks like a bronco to give the plane a few jolts in the tummy, then darts forward to resume its place ahead of the plane, deliberately slowing down to its original speed to frustrate the plane’s progress. Barney has become aware what is going on, and wig-wags a disapproving finger at the plane again. But the plane will have no part of Barney’s cautionings – he instead has a personal score to settle. Now the plane performs an under-the-belly pass of the pelican, but positions its propeller to buzz-cut and remove a large chunk of the bird’s belly feathers as he passes. The bird flaps mightily, then pulls in its wings for streamlining to gain speed, striking a beak blow directly into the plane’s tail, which glows a bright red from the throbbing at the point of impact. Time to take off the gloves for some bare-knuckle brawling, as plane and bird mix it up in a blur of fisticuffs. Suddenly, to its surprise, the plane finds itself alone in the sky, flailing its fighting wheels at no one. It looks all around to see what has become of the bird, and reacts in panic to find that the bird has climbed to a higher elevation to gain strategic position, and is now descending directly upon the plane in a high-speed power dive. The impact sends a shower of nuts and bolts from Barney’s engine “cocktail” spewing everywhere from a cloud of black smoke, and when the smoke clears, the bird is hovering victorious, wearing on its beak the still-spinning remains of the little plane’s propeller.

Now, the plane settles into some graceful aerial acrobatics, bobbing in waltz tempo to strains of “The Man on the Flying Trapeze”, tiptoeing over clouds and performing spins atop them on its wingtip. A close shot on Barney’s face depicts a look that can only be described as believing he is in 7th Heaven. But the playful plane is still looking for a little excitement – and spots it in the form of a slow-flying pelican. While Barney isn’t paying notice, the plane creeps up behind the pelican, then startles it with a honk of its horn to make way. The frightened bird dodges upward, as the little plane proceeds ahead, taking the bird’s place in the sky lanes. The pelican also has a temper, and is miffed at being passed. It speeds up, zips under the plane’s belly, and bucks like a bronco to give the plane a few jolts in the tummy, then darts forward to resume its place ahead of the plane, deliberately slowing down to its original speed to frustrate the plane’s progress. Barney has become aware what is going on, and wig-wags a disapproving finger at the plane again. But the plane will have no part of Barney’s cautionings – he instead has a personal score to settle. Now the plane performs an under-the-belly pass of the pelican, but positions its propeller to buzz-cut and remove a large chunk of the bird’s belly feathers as he passes. The bird flaps mightily, then pulls in its wings for streamlining to gain speed, striking a beak blow directly into the plane’s tail, which glows a bright red from the throbbing at the point of impact. Time to take off the gloves for some bare-knuckle brawling, as plane and bird mix it up in a blur of fisticuffs. Suddenly, to its surprise, the plane finds itself alone in the sky, flailing its fighting wheels at no one. It looks all around to see what has become of the bird, and reacts in panic to find that the bird has climbed to a higher elevation to gain strategic position, and is now descending directly upon the plane in a high-speed power dive. The impact sends a shower of nuts and bolts from Barney’s engine “cocktail” spewing everywhere from a cloud of black smoke, and when the smoke clears, the bird is hovering victorious, wearing on its beak the still-spinning remains of the little plane’s propeller.

Now, without prop or engine, Barney and the plane fall helplessly through the sky. They land, of all places, in the pilot and passenger seat of a huge two-seated fighter plane just readied for takeoff. Feeling someone within, the big plane quickly taxis, and soars off with its new flight crew into the blue. Barney, despite his mechanic’s training, has no idea how one of these new-fangled contraptions works, and stares with gaping jaw at the maze of controls on the dashboard. He jabs at buttons randomly, then tugs at the steering column. They don’t make these new planes like they used to, and the steering wheel breaks off in Barney’s hands. Without control, Barney “bear”ly averts head-on collision with another fighter. More button pushing, and the fighter does a few upward loops past the hangars, then a steep vertical climb, nearly straight up. The Earth begins to disappear below them, as Barney watches the altimeter climb to nearly the limits of its numeric readouts. Meanwhile, the thermometer is dropping to sub-zero, and the mercury is soon frozen within an icicle surrounding the lower thermometer. Outside, the wings are icing up to a nearly solid sheet. Barney’s teeth chatter uncontrollably, and he looks back to see how his co-passenger is doing The little plane is now solidly frozen inside a block of ice. Barney lets oy a vain yell for help, but is quick-frozen into his own ice block in mid-yell. Suddenly, the fighter’s progress is stopped “cold”, as the plane hits a solid sheet of ice across the sky, labeled “Ceiling Zero – Zero – Zero – Zero -….”. Gravity taking hold, the fighter falls in a dizzying descent, as the wings break off from the intense force of the air speed. The ice thaws away, releasing the little plane and Barney from their frozen sleep. But the fighter continues to disintegrate, its metal surfaces peeling away, until all that is left is Barney, the little plane, and the fighter’s powerful engine dragging them to Earth. The little plane clings terrified to Barney, but, realizing they are at least together, presses its cheek to Barney’s in an embrace and smiles a puppy-dog smile, leading Barney to give a disgruntled look to the camera as if to say “Oh, brother.” The inevitable crash occurs, and as the smoke clears, we find the camera has already transported us to the rooms of a field hospital. In a semi-private room, Barney and his plane are now bunkmates in twin hospital beds, completely laid up in traction. Barney can only shoot a disparaging glance at the plane, who still behaves like a happy puppy despite its wings and engine being bound up in bandages and casts, and wags its tail and honks its horn with a happy smile to Barney for the iris out.

Now, without prop or engine, Barney and the plane fall helplessly through the sky. They land, of all places, in the pilot and passenger seat of a huge two-seated fighter plane just readied for takeoff. Feeling someone within, the big plane quickly taxis, and soars off with its new flight crew into the blue. Barney, despite his mechanic’s training, has no idea how one of these new-fangled contraptions works, and stares with gaping jaw at the maze of controls on the dashboard. He jabs at buttons randomly, then tugs at the steering column. They don’t make these new planes like they used to, and the steering wheel breaks off in Barney’s hands. Without control, Barney “bear”ly averts head-on collision with another fighter. More button pushing, and the fighter does a few upward loops past the hangars, then a steep vertical climb, nearly straight up. The Earth begins to disappear below them, as Barney watches the altimeter climb to nearly the limits of its numeric readouts. Meanwhile, the thermometer is dropping to sub-zero, and the mercury is soon frozen within an icicle surrounding the lower thermometer. Outside, the wings are icing up to a nearly solid sheet. Barney’s teeth chatter uncontrollably, and he looks back to see how his co-passenger is doing The little plane is now solidly frozen inside a block of ice. Barney lets oy a vain yell for help, but is quick-frozen into his own ice block in mid-yell. Suddenly, the fighter’s progress is stopped “cold”, as the plane hits a solid sheet of ice across the sky, labeled “Ceiling Zero – Zero – Zero – Zero -….”. Gravity taking hold, the fighter falls in a dizzying descent, as the wings break off from the intense force of the air speed. The ice thaws away, releasing the little plane and Barney from their frozen sleep. But the fighter continues to disintegrate, its metal surfaces peeling away, until all that is left is Barney, the little plane, and the fighter’s powerful engine dragging them to Earth. The little plane clings terrified to Barney, but, realizing they are at least together, presses its cheek to Barney’s in an embrace and smiles a puppy-dog smile, leading Barney to give a disgruntled look to the camera as if to say “Oh, brother.” The inevitable crash occurs, and as the smoke clears, we find the camera has already transported us to the rooms of a field hospital. In a semi-private room, Barney and his plane are now bunkmates in twin hospital beds, completely laid up in traction. Barney can only shoot a disparaging glance at the plane, who still behaves like a happy puppy despite its wings and engine being bound up in bandages and casts, and wags its tail and honks its horn with a happy smile to Barney for the iris out.

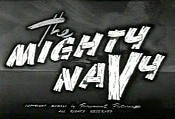

The Mighty Navy (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 11/14/41 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Abner Matthews, anim,) – For the first time in Popeye’s career, the modern navy is depicted (with animation skill greatly improved by the experience the animators were receiving in training for the realistic animation of Superman). The biggest change is the enlistment (we presume, as he was probably over draft age) of Popeye, causing a complete change of uniform, into his now familiar navy whites that would appear throughout the rest of his theatrical and early television career. At morning roll call, Popeye stands out like a sore thumb – the shortest of the young recruits, with the scrawniest build, and curiously peering around the ship, trying to figure out where the sails are at. The captain can’t believe his eyes, and picks up Popeye as if he was inspecting a rifle, looking straight into his eyeball as if checking the cleanliness of the barrel of a gun. “So, you want to be a sailor”, he states condescendingly. Popeye is insulted. “I yam a sailor. I was born a sailor, an’ there’s nothin’ wat I doesn’t know about a ship because I’m Popeye the sailor man (toot toot)!” The captain puts his knowledge to the test, first with assignment to hoist anchor. Ignoring a control panel for motorized hauling-in, Popeye takes hold of the anchor chain with his mighty muscles, and begins tugging the chain aboard bodily. However, the anchor is stuck on a rock on the bottom, and so Popeye drags the entire bow of the ship underwater, drenching the Captain. Popeye’s next test is to aim a battleship gun turret. By the time Popeye is through trying to figure out which button to push and wheel to spin, the four gun barrels are wound together in a braid. Test no. 3 is to see if Popeye can fly a plane off a launching catapult. Popeye observes that the plane is labeled “dive bomber” – and gets the wrong idea. He gets the engine started, taxis to the end of the deck, then leaps off its edge as if a diving board. The plane rises a short distance, then bends downward, executing a series of dives which Popeye verbally describes: “Jack knife, swan, twist,…and belly flopper”, as the plane sinks into the sea. “Get that man below”, shouts the furious Captain.

The Mighty Navy (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 11/14/41 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Abner Matthews, anim,) – For the first time in Popeye’s career, the modern navy is depicted (with animation skill greatly improved by the experience the animators were receiving in training for the realistic animation of Superman). The biggest change is the enlistment (we presume, as he was probably over draft age) of Popeye, causing a complete change of uniform, into his now familiar navy whites that would appear throughout the rest of his theatrical and early television career. At morning roll call, Popeye stands out like a sore thumb – the shortest of the young recruits, with the scrawniest build, and curiously peering around the ship, trying to figure out where the sails are at. The captain can’t believe his eyes, and picks up Popeye as if he was inspecting a rifle, looking straight into his eyeball as if checking the cleanliness of the barrel of a gun. “So, you want to be a sailor”, he states condescendingly. Popeye is insulted. “I yam a sailor. I was born a sailor, an’ there’s nothin’ wat I doesn’t know about a ship because I’m Popeye the sailor man (toot toot)!” The captain puts his knowledge to the test, first with assignment to hoist anchor. Ignoring a control panel for motorized hauling-in, Popeye takes hold of the anchor chain with his mighty muscles, and begins tugging the chain aboard bodily. However, the anchor is stuck on a rock on the bottom, and so Popeye drags the entire bow of the ship underwater, drenching the Captain. Popeye’s next test is to aim a battleship gun turret. By the time Popeye is through trying to figure out which button to push and wheel to spin, the four gun barrels are wound together in a braid. Test no. 3 is to see if Popeye can fly a plane off a launching catapult. Popeye observes that the plane is labeled “dive bomber” – and gets the wrong idea. He gets the engine started, taxis to the end of the deck, then leaps off its edge as if a diving board. The plane rises a short distance, then bends downward, executing a series of dives which Popeye verbally describes: “Jack knife, swan, twist,…and belly flopper”, as the plane sinks into the sea. “Get that man below”, shouts the furious Captain.

Popeye is assigned the lowest of tasks – peeling onions in the ship’s galley. A series of explosions outside call Popeye’s attention to the porthole, where he spies a fleet of battleships launching broadsides at his ship, one carrying a flag which falls just short of placing the U.S. at official war with anybody, reading “Enemy (Name Your Own).” On deck, a pair of specially skilled gunmen attempt to aim a large gun by the book, calling out coordinates for elevation, azimuth, etc., but taking so long, no shots are being fired. As Popeye sticks his head out the porthole, and avoids enemy fire in the manner of a “dodger” dodging baseballs at a carnival, an enemy shell zeroes in on the porthole, causing Popeye to duck back in, open a porthole on the opposite side of the deck, and let the shell out again. “That’s all I can stands, I can’t stands no more”, shouts the sailor. Climbing to the main deck, Popeye spies the gunners still fussing over their mathematics. “Gimme dat peashooter”, yells our hero, yanking the gun from its mounting, and holding it like he was firing a giant pistol. He scores hit after hit on the enemy fleet as if they were ducks in a shooting gallery. An aircraft carrier launches its entire armada of fighter planes at him. As the planes take off one by one, Popeye follows the etiquette of a skeet shooting match, calling for each target with the call of “Pull”, then blasting each plane from the sky. The carrier skedaddles away with the audible whimpers of a wounded dog. But the enemy has one more weapon up its sleeve – its largest of battleships, towering three times over the others, and filled to the railings with blasting cannon. Popeye knows just how to address the situation. He thrusts himself into a torpedo launcher, eats his can of spinach, revs up his feet like a torpedo propeller, and launches himself directly at the firing ship. Holding his mighty fist out before him, he scores a direct hit on the ship’s bow, reducing the vessel to a bare metal framework, which sinks below the waves. The final scene finds Popeye back on board his ship, with an assembly of crew and officers surrounding him, for a presentation. “For your exceptional performance under fire, the Navy is proud to honor you with this reward.” The Captain hands Popeye what looks like a scroll, which Popeye unrolls, revealing an illustration of himself in his old uniform, delivering a sock with his fist. “Me picture in a circle. What’s it for?”, asks the curious sailor. “The official insignia of the Navy’s bomber squadron.” The final scene shows the insignia proudly worn upon a squadron of bombers (they may be of Consolidated B-24 class), sailing through the skies on a mission, as we fade out. (Unfortunately, while this seemed to commemorate a genuine official act of the services of which the Fleischer studios could be proud, it may have only been wishful thinking. Although there are real-life instances where Popeye’s image appeared as insignia for small squadrons or on random nose imagery of bombers or fighters, and even one featuring Poopdeck Pappy. I can find no record on the internet of this insignia ever receiving official use, nor of any Navy bomber squadron associated with it. The very fact that no identifying number of a squadron is referenced in the film may provide confirmation that the award is a fake – something that Little Lulu might have been anxious to point out to Popeye a few years later.)

Popeye is assigned the lowest of tasks – peeling onions in the ship’s galley. A series of explosions outside call Popeye’s attention to the porthole, where he spies a fleet of battleships launching broadsides at his ship, one carrying a flag which falls just short of placing the U.S. at official war with anybody, reading “Enemy (Name Your Own).” On deck, a pair of specially skilled gunmen attempt to aim a large gun by the book, calling out coordinates for elevation, azimuth, etc., but taking so long, no shots are being fired. As Popeye sticks his head out the porthole, and avoids enemy fire in the manner of a “dodger” dodging baseballs at a carnival, an enemy shell zeroes in on the porthole, causing Popeye to duck back in, open a porthole on the opposite side of the deck, and let the shell out again. “That’s all I can stands, I can’t stands no more”, shouts the sailor. Climbing to the main deck, Popeye spies the gunners still fussing over their mathematics. “Gimme dat peashooter”, yells our hero, yanking the gun from its mounting, and holding it like he was firing a giant pistol. He scores hit after hit on the enemy fleet as if they were ducks in a shooting gallery. An aircraft carrier launches its entire armada of fighter planes at him. As the planes take off one by one, Popeye follows the etiquette of a skeet shooting match, calling for each target with the call of “Pull”, then blasting each plane from the sky. The carrier skedaddles away with the audible whimpers of a wounded dog. But the enemy has one more weapon up its sleeve – its largest of battleships, towering three times over the others, and filled to the railings with blasting cannon. Popeye knows just how to address the situation. He thrusts himself into a torpedo launcher, eats his can of spinach, revs up his feet like a torpedo propeller, and launches himself directly at the firing ship. Holding his mighty fist out before him, he scores a direct hit on the ship’s bow, reducing the vessel to a bare metal framework, which sinks below the waves. The final scene finds Popeye back on board his ship, with an assembly of crew and officers surrounding him, for a presentation. “For your exceptional performance under fire, the Navy is proud to honor you with this reward.” The Captain hands Popeye what looks like a scroll, which Popeye unrolls, revealing an illustration of himself in his old uniform, delivering a sock with his fist. “Me picture in a circle. What’s it for?”, asks the curious sailor. “The official insignia of the Navy’s bomber squadron.” The final scene shows the insignia proudly worn upon a squadron of bombers (they may be of Consolidated B-24 class), sailing through the skies on a mission, as we fade out. (Unfortunately, while this seemed to commemorate a genuine official act of the services of which the Fleischer studios could be proud, it may have only been wishful thinking. Although there are real-life instances where Popeye’s image appeared as insignia for small squadrons or on random nose imagery of bombers or fighters, and even one featuring Poopdeck Pappy. I can find no record on the internet of this insignia ever receiving official use, nor of any Navy bomber squadron associated with it. The very fact that no identifying number of a squadron is referenced in the film may provide confirmation that the award is a fake – something that Little Lulu might have been anxious to point out to Popeye a few years later.)

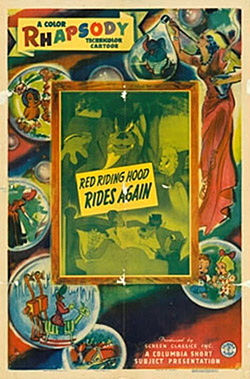

December 8, 1941, arrived – the date on which President Roosevelt announced a state of war existed between the U.S. and Japan. Animators of course couldn’t instantly adapt their product to full-scale war, production time being needed to create new material. So a few military-related but not yet wartime cartoons continued to flow down the distribution pipeline, while the studios geared up for an all-out war effort. One of the first was Red Riding Hood Rides Again (Columbia/Screen Gems, Color Rhapsody, 12/25/41 – Sid Marcus, dir.) – an updated version of the old tale, with all the modern conveniences. Red put-puts her way through the forest on a pint-sized motor scooter. The wolf (with the usual type-cast voicing of Billy Bletcber), tries to “Turn on the old poisonality” by donning masks of various movie stars and trying to thumb for a ride, including caricatures of Clark Gable, Mickey Rooney, Groucho Marx, Lionel Barrymore, and George Raft. Red is not taken in by any of the masks, but likes the wolf’s real face when she sees it, thinking he is a police dog. But an owl pops out of a hatch in the side of a tree, giving out a warning in police-broadcast style that the “doggie: is a wolf. “Are you gonna eat my Grandma?” asks the naive Red. In actuality, her comment puts the idea into the wolf’s head for the first time. While denying intentions to do such a foul deed, he whips out a whittling knife, and carves wood shavings off the side of a tree into a box marked “Toothpicks”. The wolf, out of mock sheer curiosity, asks where “the old girl” lives. Red gives complex road directions, which the wolf takes down in shorthand on a miniature wrist-typewriter fastened to his shirt cuff. The wolf then feigns sleepiness, and settles down for a nap while Red proceeds on her way. The minute she is gone, the wolf produces from nowhere a sporty yellow plane, streamlined for speed, and soars like a comet across the forest to the general vicinity of Grandma’s house. He looks around for what Red described as a cottage “hidden deep in the woods”. It doesn’t take a Sherlock Holmes to track it down – as “Grandma’s House” appears on a bright neon sign on a nearby cottage’s roof, with added readouts of “Come and Get It”, and “Blue Plate Dinners 35 cents”. Within a few moments, the wolf is liberally shaking salt and pepper over the sleeping Grandma. But a phone call arouses the old lady, who calmly tells the wolf to hold on while she takes the call. It is from a friend, informing her that Jimmy Dorsey’s band is in town. Grandma immediately gussies up to “Cut a rug”, and exits for a night on the town, leaving the frustrated wolf with the words, “Don’t wait up for me.” But along cones Red – substitute meat on the table. The usual “What a big _______ you have” bit is played fairly straightforwardly, with some mild sight-gag assist. But just as the wolf gets to the “eat you” part, there is a knock at the front door. Ir is a telegram for the wolf, advising him of his draft notice, and to report immediately for training. A drill sergeant appears from nowhere, slapping upon the wolf an army hat, uniform, and full backpack. “Forward march!” yells the sergeant, as the wolf is marched off with a full military band escort, and even a surprise fly-through the cottage of a B-19 bomber, for the iris out.

December 8, 1941, arrived – the date on which President Roosevelt announced a state of war existed between the U.S. and Japan. Animators of course couldn’t instantly adapt their product to full-scale war, production time being needed to create new material. So a few military-related but not yet wartime cartoons continued to flow down the distribution pipeline, while the studios geared up for an all-out war effort. One of the first was Red Riding Hood Rides Again (Columbia/Screen Gems, Color Rhapsody, 12/25/41 – Sid Marcus, dir.) – an updated version of the old tale, with all the modern conveniences. Red put-puts her way through the forest on a pint-sized motor scooter. The wolf (with the usual type-cast voicing of Billy Bletcber), tries to “Turn on the old poisonality” by donning masks of various movie stars and trying to thumb for a ride, including caricatures of Clark Gable, Mickey Rooney, Groucho Marx, Lionel Barrymore, and George Raft. Red is not taken in by any of the masks, but likes the wolf’s real face when she sees it, thinking he is a police dog. But an owl pops out of a hatch in the side of a tree, giving out a warning in police-broadcast style that the “doggie: is a wolf. “Are you gonna eat my Grandma?” asks the naive Red. In actuality, her comment puts the idea into the wolf’s head for the first time. While denying intentions to do such a foul deed, he whips out a whittling knife, and carves wood shavings off the side of a tree into a box marked “Toothpicks”. The wolf, out of mock sheer curiosity, asks where “the old girl” lives. Red gives complex road directions, which the wolf takes down in shorthand on a miniature wrist-typewriter fastened to his shirt cuff. The wolf then feigns sleepiness, and settles down for a nap while Red proceeds on her way. The minute she is gone, the wolf produces from nowhere a sporty yellow plane, streamlined for speed, and soars like a comet across the forest to the general vicinity of Grandma’s house. He looks around for what Red described as a cottage “hidden deep in the woods”. It doesn’t take a Sherlock Holmes to track it down – as “Grandma’s House” appears on a bright neon sign on a nearby cottage’s roof, with added readouts of “Come and Get It”, and “Blue Plate Dinners 35 cents”. Within a few moments, the wolf is liberally shaking salt and pepper over the sleeping Grandma. But a phone call arouses the old lady, who calmly tells the wolf to hold on while she takes the call. It is from a friend, informing her that Jimmy Dorsey’s band is in town. Grandma immediately gussies up to “Cut a rug”, and exits for a night on the town, leaving the frustrated wolf with the words, “Don’t wait up for me.” But along cones Red – substitute meat on the table. The usual “What a big _______ you have” bit is played fairly straightforwardly, with some mild sight-gag assist. But just as the wolf gets to the “eat you” part, there is a knock at the front door. Ir is a telegram for the wolf, advising him of his draft notice, and to report immediately for training. A drill sergeant appears from nowhere, slapping upon the wolf an army hat, uniform, and full backpack. “Forward march!” yells the sergeant, as the wolf is marched off with a full military band escort, and even a surprise fly-through the cottage of a B-19 bomber, for the iris out.

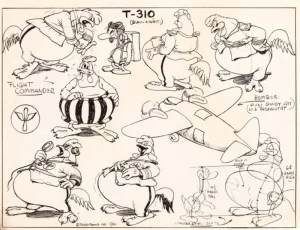

Another presumably pre-Pearl Harbor production was Flying Fever (Terrytoons/Fox, Gandy Goose, 12/26/41 – Mannie Davis, dir.). The film opens with what appears to be an aerial dogfight in progress, with planes criss-crossing all over the skies, and some being periodically shot down in flames. The camera pulls back to reveal they ate all toys, being thrown Into the air by animals of the barnyard, with Gandy Goose manning a toy machine gun for target practice in his effort to maintain home defense. Strutting along in a heavy obese walk comes Captain Rudy Rooster. One of the planes dips and swoops in a circular flight path around his midriff. Rudy’s head turns and follows to see where it goes. Suddenly, Gandy’s gun is heard from behind him, and Rudy gets peppered in the tail. He confronts the trigger-happy goose. “Did you do that?”, pointing to his ruffled feathers. Gandy replies, “Oh, it was just a lucky shot.” Rudy at first appears miffed – but surprisingly changes attitude. “Lucky, nothing. It was a GREAT shot. How would you like to join the air force?” Gandy, consistent with his earlier appearance in “The Goose Flies High”, again confesses it’s been his lifelong ambition to become a pilot. Rudy escorts Gandy to a training field, where Gandy is blindfolded, provided with a toy donkey’s tail from a “pin the tail on the donkey” game, then is placed in the latest in testing apparatus – a barrel-shaped chamber, mounted into a large rotating gyroscope, which spins and pivots the goose every which way. Gandy stumbles out as the unseen world spins around him , and attempts to walk forward toward a donkey poster Rudy has hung on a fence. He fastens the tail to the donkey’s snout. Determined to do better, Gandy climbs back in for another barrel spin, and tries again. Rudy is busy laughing at Gandy’s first shot, and fails to see the goose reapproaching – allowing Gandy to stick the pin into Rudy’s own tail. A camera wipe, and Gandy is told he is ready for his solo. “Solo?” inquires Gandy, and clears his throat, then begins emitting ear-splitting vocal cadenzas in operatic style. “Not that!” shouts Rudy, and gets Gandy straightened out, by tossing him into the cockpit of a small plane. At a command of “Contact”, Gandy is off. Rudy radios Gandy to relax. Gandy takes the instruction quite literally, leaning back in his seat and putting his feet up on the dashboard. The plane starts to swerve uncontrollably, and steers Gandy right unto a rainstorm. As Gandy hits a crosswind, he open an umbrella with one hand over his head. The wind-driven rain flies upwards into the inner curve of the umbrella fabric, and a pair of passing ducks land upside down to make use of the water as an inverted duck pond. Gandy lets go of the umbrella, and it falls, ducks, water, and all, toward the field. “It’s raining up here” radios Gandy to Rudy. “A little water never hurt anybody”, responds Rudy, just as the water-filled umbrella drenches him in a direct hit from above. Gandy attempts to throw out an anchor, but winds up dangling behind the plane with it from its mooring rope. He cuts the rope, allowing the anchor to fall in a near miss of Rudy. The plane then dives and buzzes Rudy, reducing him to his underwear. Gandy crashes through a hangar, emerging in his cockpit seat but minus his plane. One of his plane’s tires flies into the air, making a “ringer” around the goose’s neck. Gandy falls back to earth, running over Rudy with the tire, before the wheel deflates, depositing Gandy on the ground.

Another presumably pre-Pearl Harbor production was Flying Fever (Terrytoons/Fox, Gandy Goose, 12/26/41 – Mannie Davis, dir.). The film opens with what appears to be an aerial dogfight in progress, with planes criss-crossing all over the skies, and some being periodically shot down in flames. The camera pulls back to reveal they ate all toys, being thrown Into the air by animals of the barnyard, with Gandy Goose manning a toy machine gun for target practice in his effort to maintain home defense. Strutting along in a heavy obese walk comes Captain Rudy Rooster. One of the planes dips and swoops in a circular flight path around his midriff. Rudy’s head turns and follows to see where it goes. Suddenly, Gandy’s gun is heard from behind him, and Rudy gets peppered in the tail. He confronts the trigger-happy goose. “Did you do that?”, pointing to his ruffled feathers. Gandy replies, “Oh, it was just a lucky shot.” Rudy at first appears miffed – but surprisingly changes attitude. “Lucky, nothing. It was a GREAT shot. How would you like to join the air force?” Gandy, consistent with his earlier appearance in “The Goose Flies High”, again confesses it’s been his lifelong ambition to become a pilot. Rudy escorts Gandy to a training field, where Gandy is blindfolded, provided with a toy donkey’s tail from a “pin the tail on the donkey” game, then is placed in the latest in testing apparatus – a barrel-shaped chamber, mounted into a large rotating gyroscope, which spins and pivots the goose every which way. Gandy stumbles out as the unseen world spins around him , and attempts to walk forward toward a donkey poster Rudy has hung on a fence. He fastens the tail to the donkey’s snout. Determined to do better, Gandy climbs back in for another barrel spin, and tries again. Rudy is busy laughing at Gandy’s first shot, and fails to see the goose reapproaching – allowing Gandy to stick the pin into Rudy’s own tail. A camera wipe, and Gandy is told he is ready for his solo. “Solo?” inquires Gandy, and clears his throat, then begins emitting ear-splitting vocal cadenzas in operatic style. “Not that!” shouts Rudy, and gets Gandy straightened out, by tossing him into the cockpit of a small plane. At a command of “Contact”, Gandy is off. Rudy radios Gandy to relax. Gandy takes the instruction quite literally, leaning back in his seat and putting his feet up on the dashboard. The plane starts to swerve uncontrollably, and steers Gandy right unto a rainstorm. As Gandy hits a crosswind, he open an umbrella with one hand over his head. The wind-driven rain flies upwards into the inner curve of the umbrella fabric, and a pair of passing ducks land upside down to make use of the water as an inverted duck pond. Gandy lets go of the umbrella, and it falls, ducks, water, and all, toward the field. “It’s raining up here” radios Gandy to Rudy. “A little water never hurt anybody”, responds Rudy, just as the water-filled umbrella drenches him in a direct hit from above. Gandy attempts to throw out an anchor, but winds up dangling behind the plane with it from its mooring rope. He cuts the rope, allowing the anchor to fall in a near miss of Rudy. The plane then dives and buzzes Rudy, reducing him to his underwear. Gandy crashes through a hangar, emerging in his cockpit seat but minus his plane. One of his plane’s tires flies into the air, making a “ringer” around the goose’s neck. Gandy falls back to earth, running over Rudy with the tire, before the wheel deflates, depositing Gandy on the ground.

Another camera wipe, and Gandy is certified for parachute jumping with full equipment. Carrying a rifle, grenades, and other assorted ammunition, he is hoisted by Rudy into a waiting bomber. Rudy is by now actually hoping for the worst for Gandy, sending him off with the farewell of “I’ll see you in China.” The plane rises, to elevations of 10,000, 15,000, and 20,000 feet. Gandy peers out the open door of the bomber, seeing the entire globe as a small circle below him. Rudy radios a repeated reminder to count to ten slowly before pulling the ripcord. “Geronimo” hesitantly utters Gandy – but a mechanical boot mounted in the cabin wall behind him gives him added incentive to jump, kicking him forcefully out of the plane. Gandy embellishes on the counting, adding the verses of the old nursery rhyme, “One, two, button my shoe. Three, four, shut the door…” His counting is so slow that he slams into Rudy below before he is even halfway through the count. True to Rudy’s premonition, Gandy and the rooster forcefully burrow into the ground, through the entire planet, and come up upside down in China. Seated on the ground, Gandy finally reaches the line, “Nine, ten, a big fat hen – and pull the cord.” Rudy lunges for him, but the opening parachute billows and lifts Gandy away, out of the film. All that is left is the falling weaponry from Gandy’s backpack, which explodes around Rudy, leaving the battered and disheveled rooster to drum his fingers on the ground in frustration, for the iris out.

Another camera wipe, and Gandy is certified for parachute jumping with full equipment. Carrying a rifle, grenades, and other assorted ammunition, he is hoisted by Rudy into a waiting bomber. Rudy is by now actually hoping for the worst for Gandy, sending him off with the farewell of “I’ll see you in China.” The plane rises, to elevations of 10,000, 15,000, and 20,000 feet. Gandy peers out the open door of the bomber, seeing the entire globe as a small circle below him. Rudy radios a repeated reminder to count to ten slowly before pulling the ripcord. “Geronimo” hesitantly utters Gandy – but a mechanical boot mounted in the cabin wall behind him gives him added incentive to jump, kicking him forcefully out of the plane. Gandy embellishes on the counting, adding the verses of the old nursery rhyme, “One, two, button my shoe. Three, four, shut the door…” His counting is so slow that he slams into Rudy below before he is even halfway through the count. True to Rudy’s premonition, Gandy and the rooster forcefully burrow into the ground, through the entire planet, and come up upside down in China. Seated on the ground, Gandy finally reaches the line, “Nine, ten, a big fat hen – and pull the cord.” Rudy lunges for him, but the opening parachute billows and lifts Gandy away, out of the film. All that is left is the falling weaponry from Gandy’s backpack, which explodes around Rudy, leaving the battered and disheveled rooster to drum his fingers on the ground in frustration, for the iris out.

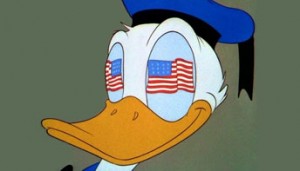

Due to its sheer volume of footage, and the fact that not all of it has probably yet been located and/or declassified, this article series will not attempt to comprehensively catalog all training, bond, and propaganda films from Disney studios in which planes appeared (including a string of bond commercials released in Canada only). It will instead feature only selected shorts among the vast output, focusing on those that probably had the widest screening audiences. The New Spirit (Disney, public service film, 1/23/42 – Wilfred Jackson/Ben Sharpsteen, dir.) is a good representative example. It was among the first animated products to make it to the screen, identifying by name the foes with which we were at war, and attempting to rally patriotic spirit in support of the war effort. Billed as a “special attraction” on theater posters, unsuspecting audiences were led to believe they would be viewing a new entertaining Donald cartoon as a bonus extra to the standard theater schedule. While there are some entertaining moments and a few laughs, it becomes quickly obvious that this film has an agenda and ulterior purpose – get the public to pay their income taxes, to support general armament. Gone is the usual distributing credit to RKO – instead, a special indicia appears under the standard headshot of Donald’s face, reading, “This film distributed and exhibited under the auspices of the War Activities Committee, Motion Picture Industry”.

Due to its sheer volume of footage, and the fact that not all of it has probably yet been located and/or declassified, this article series will not attempt to comprehensively catalog all training, bond, and propaganda films from Disney studios in which planes appeared (including a string of bond commercials released in Canada only). It will instead feature only selected shorts among the vast output, focusing on those that probably had the widest screening audiences. The New Spirit (Disney, public service film, 1/23/42 – Wilfred Jackson/Ben Sharpsteen, dir.) is a good representative example. It was among the first animated products to make it to the screen, identifying by name the foes with which we were at war, and attempting to rally patriotic spirit in support of the war effort. Billed as a “special attraction” on theater posters, unsuspecting audiences were led to believe they would be viewing a new entertaining Donald cartoon as a bonus extra to the standard theater schedule. While there are some entertaining moments and a few laughs, it becomes quickly obvious that this film has an agenda and ulterior purpose – get the public to pay their income taxes, to support general armament. Gone is the usual distributing credit to RKO – instead, a special indicia appears under the standard headshot of Donald’s face, reading, “This film distributed and exhibited under the auspices of the War Activities Committee, Motion Picture Industry”.

It is uncertain which director should receive credit for which half of the film, but the mood and style of part one and part two are decidedly different from one another. The film opens with a theme song, sung with all the patriotic fervor he can muster by a now familiar voice to Disney fans – Cliff Edwards (the voice of Jiminy Cricket). A quartet of identical Donald Ducks parade in unison against a silvery, indistinct background. Then the camera pulls back to reveal the real Donald Duck, dancing to the tune in front of a four-panel folding dressing mirror. He marches away to one side, while all but one of the reflected ducks follow, the fourth one being out of step, and only responding in delayed fashion as he attempts to exit in the wrong direction. The theme song finishes, emitting from a large floor-model radio, with lighted dials and speaker fashioned to resemble a giant face. Donald’s eyes transform into images of an American flag being hoisted into position on a flagpole, moved by the song’s message. An announcer declares – “Yes, there is a new spirit…of a free people, united again in a common cause to stamp tyranny from the earth.” Already, we know this isn’t your daddy’s Donald Duck cartoon. “Our very shores have been attacked” continues the announcer, arousing the Donald temper that generally no one would want to voluntarily arouse. “That is not right” complains Donald, slamming his hat on the ground. “Your whole country is mobilizing for total war” continues the voice. “Your country needs you.” Patriotism aroused, Donald disappears for a moment, returning wearing everything from his closet that resembles a weapon or a military uniform (seemingly forgetting he is already wearing a sailor suit), and stands ready to enlist. But the announcer insists there’s something else important that he can do. “You won’t get a medal for doing it”, he says. Modest Donald replies, “Oh, that’s all right.” The announcer continues to arouse Donald’s curiosity as to the assignment, until Donald is literally pleading with the radio to tell him what to do. “Pay your income taxes.” With a look of utter deflation, Donald falls into a grumbling heap on the floor – possibly the biggest laugh in the film.

It is uncertain which director should receive credit for which half of the film, but the mood and style of part one and part two are decidedly different from one another. The film opens with a theme song, sung with all the patriotic fervor he can muster by a now familiar voice to Disney fans – Cliff Edwards (the voice of Jiminy Cricket). A quartet of identical Donald Ducks parade in unison against a silvery, indistinct background. Then the camera pulls back to reveal the real Donald Duck, dancing to the tune in front of a four-panel folding dressing mirror. He marches away to one side, while all but one of the reflected ducks follow, the fourth one being out of step, and only responding in delayed fashion as he attempts to exit in the wrong direction. The theme song finishes, emitting from a large floor-model radio, with lighted dials and speaker fashioned to resemble a giant face. Donald’s eyes transform into images of an American flag being hoisted into position on a flagpole, moved by the song’s message. An announcer declares – “Yes, there is a new spirit…of a free people, united again in a common cause to stamp tyranny from the earth.” Already, we know this isn’t your daddy’s Donald Duck cartoon. “Our very shores have been attacked” continues the announcer, arousing the Donald temper that generally no one would want to voluntarily arouse. “That is not right” complains Donald, slamming his hat on the ground. “Your whole country is mobilizing for total war” continues the voice. “Your country needs you.” Patriotism aroused, Donald disappears for a moment, returning wearing everything from his closet that resembles a weapon or a military uniform (seemingly forgetting he is already wearing a sailor suit), and stands ready to enlist. But the announcer insists there’s something else important that he can do. “You won’t get a medal for doing it”, he says. Modest Donald replies, “Oh, that’s all right.” The announcer continues to arouse Donald’s curiosity as to the assignment, until Donald is literally pleading with the radio to tell him what to do. “Pay your income taxes.” With a look of utter deflation, Donald falls into a grumbling heap on the floor – possibly the biggest laugh in the film.

One can only imagine what Hugh Harman must have thought, seeing his medium turned around and inside out to incite the exact opposite emotions and thinking from his own masterpiece, Peace on Earth. The Motion Picture Academy was likewise as fickle. Once praising by nomination Harman’s work, they now nominated the Donald short in the category of “Best Documentary” for its own certificate. What changes politics, current events, and the dropping of bombs can arouse in a populace in a scant two years.

Next Time: America flies on.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

That rotoscoped Irish tenor in “Aviation Vacation” is hideous! He looks like something out of “Old Glory”!

Before “Flying Fever”, Gandy Goose took to the skies in two cartoons featuring the overstuffed rooster officer, in which he signed up for two other branches of the military. In “The Home Guard” (Terrytoons/Fox, 7/3/41 — Mannie Davis, dir.), Gandy takes off in a homemade airplane similar to those in “Plane Goofy” — just a box with a propeller, wheels, and a broom for a tail — as he battles a couple of “Fifth Columnists”: two vultures he found hiding literally inside one of five columns holding up the portico of a Greek Revival-style building.

And in “The One-Man Navy” (5/9/41 — Mannie Davis, dir.), Gandy is in a rowboat on the ocean laying mines: that is, explosive eggs laid by hens to whom he has fed sticks of dynamite. The hens sit four abreast in an apparatus consisting of a long, narrow box with a network of chutes. But when a submarine manned by enemy pirates attacks the rowboat, the chickens flap their wings and take Gandy into the wild blue yonder, where he “shells” the sub into submission with exploding eggs.

Both of these cartoons end with Gandy receiving the congratulations of his commanding officer and a kiss from his girlfriend — who, curiously, is named “Jenny” in the first cartoon, but “Agnes” in the second!

You’ve identified one of the masks worn by the Wolf in RED RIDING HOOD RIDES AGAIN as Lionel Barrymore – that is incorrect. The actor is William Powell from the THIN MAN series.

Re “Dumbombers for Defense,” in an example of life imitating art, “Dumbo” became the military nickname for US Navy flying boats used for air-sea rescue.

“Uncle Joey” (Terrytoons/Fox, 18/4/41 — Mannie Davis, dir.) is another example of a by now familiar scenario, in which the mice in a toy store fend off a cat with all the toy weapons at their disposal — including an airborne assault by a squadron of toy airplanes.

In “Cinderella Goes to a Party” (Columbia Color Rhapsody, 1942), a WWII take on the story, Cinderella goes to a USO party not in a coach, but in a “B19 1/2” plane that the Fairy Godmother makes from metal pots and pans “on the priority list.” At the end of the short, she flies away with the Prince in a similar plane. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKsDuwof1fg

In “The Hungry Goat” (Famous Studios, 1943), a pilotless plane takes Popeye for a ride by getting his clothing snagged on a bomb hanging from the plane. https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2z1m4k

Popeye’s white uniform would become better fitting over the years as his character gradually deteriorated. At least he’s still got his moxie at this point.

To me, it’s glaringly obvious that Famous/Paramount was late to the game with color-I wonder how much better the Popeye shorts would’ve looked had Famous sprung the extra $$$ for Technicolor?

Amusingly, a couple of days ago TCM ran SALT WATER DAFFY. Not the cartoon, but a 1933 two-reeler with Jack Haley, Shemp Howard and Lionel Stander. The usual nonsense about two goofballs accidentally enlisting and running afoul of a mean non-com.