It’s amazing how diametrically opposite two words can get with just one change of a vowel. Each of these words is something to think about, as we begin to emerge from over a year of COVID-induced hibernation or hermitage. A lucky few of us have maintained and monitored their weight. A good deal more are probably noting bulges and flaps where flat and tight skin once reigned. Oh, how those gym memberships will likely become hot commodities again, as new or returning clients labor in feeble hope of reviving their sagging metabolisms.

Under these circumstances, it may serve as a refreshing inspiration to see how our animated favorites have dealt in the past (or fallen prey to) their own weighty problems, and the various “quick fix” methods they have endeavored to employ to return to their formerly svelte physiques. To present both sides of the picture, we’ll smatter our survey with some memorable instances of characters who revel in their obesity, content to pile on the pounds to uphold the noble cause of pure gluttony.

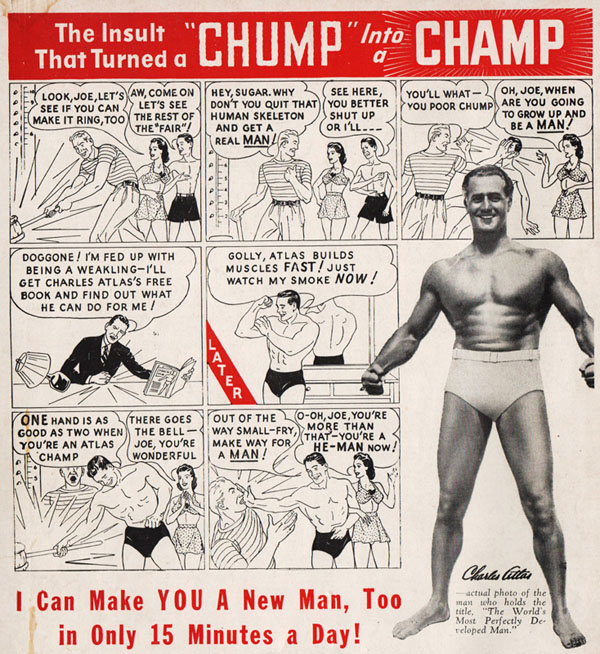

It’s hard to know from where the idea of formal exercise first sprung. Although one would presume that various military units of ancient days had some forms of training programs for qualification, and the early Olympic games and other athletic competitions certainly would have presented incentive for honing one’s physical skills, it is my guess that for the average serf or peasant, there would have been little need to worry about weight-watching. The standards of living and grueling hours of labor required of an average worker would have made the challenge be to amass enough free time or calorie-loaded food to be able to gain weight, with normal life activities relentlessly burning the poundage off and famines and lack of finances depriving the average Joe of ability to replenish what was lost. It’s hard to say whether early housewives, lacking the super-strenuous activities that their male counterparts often endured, would have been in the same position as the male population (though they would have undoubtedly shared in their spouse’s poverty). Certainly, in early cartoons and in the comic strips, it became quite the stereotype to depict wives as three times the size of their pipsqueak husbands, often rolling in fat they sought desperately to conceal with the latest fashions at the expense of their husband’s pocketbook. There may perhaps have been a grain of truth in this early imagery, as, until the advent of the industrial revolution began to lighten the load for the male worker, the little woman at home would seem to have greater opportunities for moments of physical idleness, and thus be more prone to flare-ups of weight gain over the years as metabolic processes diminished in capacity. It is perhaps from these factors that a degree of interest in obtaining forms of exercise seems to have developed somewhere around the 1920’s.

Several new inventions also appear to have contributed to the popularity of exercise at about these times. The proliferation of radio sets brought new human voices into the home, allowing “inspirational” speakers to impress upon the public their thoughts and ideas both on fashion and in how the “ideal” human being should appear and conduct himself/herself. Amidst these utterances upon various forms of self-improvement, someone hit upon the idea of encouraging exercise through the medium of radio. The idea appears to have taken off rapidly, with those persons spending time around the house setting aside periods of the day to follow what must at the time have seemed like the modern equivalent of personalized coaching, through a commanding (or at times merely patronizing) instructional voice over the airwaves. The concept of the morning exercise show over many a broadcast station was thus born. At about this same time, a new product also appears on the shelves at your local record dealer – the exercise record training program. Album sets of 78 rpm records would assert that following along with the simple instructions on the discs would guarantee melting away of the pounds and building up of muscle tone. While actual sales figures for such records are likely undocumented, the facts that some of such sets still show up from time to time in collector’s circles indicates that at least some were lured by the promises into belief that they could take home their instructor to assist them at a more convenient time of the day or in the event they slept through the morning broadcast, potentially with at least the same results as the live announcements of the A.M. schedule. Of course, a wrinkle these consumers probably didn’t reckon on until they actually tried the courses at home was the sheer shortness of playing time of the records themselves, requiring a new side to be placed upon the turntable every three or so minutes, and preventing any one exercise from continuing for more than a three minute time allotment.

It would be genuinely surprising if taking a mere four to eight repetitive movements of any kind during the course of such playing time would provide any measurable benefit to the listener, and instead would seem to have provided insufficient opportunity to even break into a sweat. Once in a while, the usefulness of an exercise would be further hampered by the sheer amount of time which would have been necessary to effectively prepare for it, becoming literally impossible to perform together with the record in the meager time allotment the recording provided. (I own an unintendedly hilarious example of this, where a record instructs the listener to perform situps by means of bracing one’s legs and ankles under a piece of heavy furniture. This is the last exercise on the side, and one can comically envision someone trying to dive for the nearest bureau or chest of drawers to get their feet properly planted in place before the announcer, knowing how quickly the record will run out of groove space. Inevitably the announcer would beat the listener to the draw, leaving him or her to hear needle scratch before being quite ready to even begin. The fad for pre-recorded voice thus does not appear to have caught on sufficiently to replace the need for a live announcer, who could at least space apart his exercise routines with a pause for an anecdote or commercial to let his listeners catch up with him (or at least catch their breath), and who could choose to continue an exercise for virtually as long as deemed necessary to actually burn off a few calories. Yet, the recorded voice would achieve a resurgence of interest many years later, in the form of long play albums such as Jane Fonda’s Workout, or instructional VHS tapes which could provide up to a two hour session of meaningful exercise, accompanied by music and the inspirational visuals of watching others sweat it out, yet seem to do it effortlessly.

It would be genuinely surprising if taking a mere four to eight repetitive movements of any kind during the course of such playing time would provide any measurable benefit to the listener, and instead would seem to have provided insufficient opportunity to even break into a sweat. Once in a while, the usefulness of an exercise would be further hampered by the sheer amount of time which would have been necessary to effectively prepare for it, becoming literally impossible to perform together with the record in the meager time allotment the recording provided. (I own an unintendedly hilarious example of this, where a record instructs the listener to perform situps by means of bracing one’s legs and ankles under a piece of heavy furniture. This is the last exercise on the side, and one can comically envision someone trying to dive for the nearest bureau or chest of drawers to get their feet properly planted in place before the announcer, knowing how quickly the record will run out of groove space. Inevitably the announcer would beat the listener to the draw, leaving him or her to hear needle scratch before being quite ready to even begin. The fad for pre-recorded voice thus does not appear to have caught on sufficiently to replace the need for a live announcer, who could at least space apart his exercise routines with a pause for an anecdote or commercial to let his listeners catch up with him (or at least catch their breath), and who could choose to continue an exercise for virtually as long as deemed necessary to actually burn off a few calories. Yet, the recorded voice would achieve a resurgence of interest many years later, in the form of long play albums such as Jane Fonda’s Workout, or instructional VHS tapes which could provide up to a two hour session of meaningful exercise, accompanied by music and the inspirational visuals of watching others sweat it out, yet seem to do it effortlessly.

Animation’s first encounters with exercise (to the extent presently known, owing again to the drastic shortage of available silent animation for study) thus centers upon the popularity of the radio morning exercise program. Radio Riot (Fleischer/Paramount, 2/13/30, Dave Fleischer, dir.), spends about a third of its footage on the subject, in a series of spot gags covering a typical broadcast day from a woodland radio station, presided over by a frog (with breath so bad he wilts the microphone, which in turn spritzes him with mouthwash). The frog begins broadcasting instructions for morning calisthenics, with a radio receiver in someone’s home performing the stretching exercises itself. The table on which the set is standing gets into the act, bouncing on its legs, then doing a reverse backflip as the radio set balances on top. Then, as the announcer voice begins to transform into the voice of veteran comic recording star Billy Murray, a goldfish in a bowl responds to the instruction to “put a wiggle on”, and performs a serpentine maneuver around and around inside its bowl. Miraculously, the fish somehow wiggles itself right through the glass side of the bowl without breaking it – then, finding himself in mid-air, attempts to re-enter the bowl but is unable to re-penetrate the glass, and falls to expire on the table. The exercises continue as a large spider, snoring in bed, is awakened by his alarm clock to catch the broadcast. Now Mr. Murray gets to shine with a tongue-in-cheek description of the next exercise: “Open the window. Place your teeth on the dresser. Rest the left knee on the right hip, and twist both ankles around the neck several times.” It’s too bad the animators didn’t try to give us a visual depiction of this maneuver – but our brains paint a pretty picture anyway.

Animation’s first encounters with exercise (to the extent presently known, owing again to the drastic shortage of available silent animation for study) thus centers upon the popularity of the radio morning exercise program. Radio Riot (Fleischer/Paramount, 2/13/30, Dave Fleischer, dir.), spends about a third of its footage on the subject, in a series of spot gags covering a typical broadcast day from a woodland radio station, presided over by a frog (with breath so bad he wilts the microphone, which in turn spritzes him with mouthwash). The frog begins broadcasting instructions for morning calisthenics, with a radio receiver in someone’s home performing the stretching exercises itself. The table on which the set is standing gets into the act, bouncing on its legs, then doing a reverse backflip as the radio set balances on top. Then, as the announcer voice begins to transform into the voice of veteran comic recording star Billy Murray, a goldfish in a bowl responds to the instruction to “put a wiggle on”, and performs a serpentine maneuver around and around inside its bowl. Miraculously, the fish somehow wiggles itself right through the glass side of the bowl without breaking it – then, finding himself in mid-air, attempts to re-enter the bowl but is unable to re-penetrate the glass, and falls to expire on the table. The exercises continue as a large spider, snoring in bed, is awakened by his alarm clock to catch the broadcast. Now Mr. Murray gets to shine with a tongue-in-cheek description of the next exercise: “Open the window. Place your teeth on the dresser. Rest the left knee on the right hip, and twist both ankles around the neck several times.” It’s too bad the animators didn’t try to give us a visual depiction of this maneuver – but our brains paint a pretty picture anyway.

Instead, the spider performs some multi-hand maneuvers with Indian clubs (sort of weighted bowling pins), takes his morning shower, brushes his teeth, then goes right back to bed again. A final exercise has two mice using a cat’s whiskers for pulling exercises resembling a gym’s rope-pull weight lifts, until the cat objects, and offscreen, presumably chalks up a two-course dinner. (Though off the subject of this article, stick around for the ending of this film, as Billy Muttay reappears again as the narrator of a children’s bedtime story program just before sign-off, in a hilariously overplayed tale of a monstrous creature that devours children from one to ten, guaranteed to give his listeners goose pimples and a double case of insomnia until next morning.) One final note regarding this production is that this film nearly didn’t survive the years to present itself to television audiences, being another Paramount negative that, in addition to one nitrate deterioration flash on the visual, suffered major damage to the soundtrack element. Inspection of the track issued to 16mm reveals that, while the breaks are well re-cemented together so that no audible pops are detected, the master must have broken in at least seven places at the beginnings of various shots (original splices presumably having severed, and frames of silence lost at the beginning of each scene), with the result that the film grows more and more progressively out of sync starting from about a quarter of the way along, placing Murray’s extended bedtime story several seconds out of sync by the end of the film. I and another poster on YouTube have expended considerable time to repair the gaps and restore the film to proper synchronization. The current YouTube resync came out about as good as my own, so I let such video stand for itself in the embed below.

Instead, the spider performs some multi-hand maneuvers with Indian clubs (sort of weighted bowling pins), takes his morning shower, brushes his teeth, then goes right back to bed again. A final exercise has two mice using a cat’s whiskers for pulling exercises resembling a gym’s rope-pull weight lifts, until the cat objects, and offscreen, presumably chalks up a two-course dinner. (Though off the subject of this article, stick around for the ending of this film, as Billy Muttay reappears again as the narrator of a children’s bedtime story program just before sign-off, in a hilariously overplayed tale of a monstrous creature that devours children from one to ten, guaranteed to give his listeners goose pimples and a double case of insomnia until next morning.) One final note regarding this production is that this film nearly didn’t survive the years to present itself to television audiences, being another Paramount negative that, in addition to one nitrate deterioration flash on the visual, suffered major damage to the soundtrack element. Inspection of the track issued to 16mm reveals that, while the breaks are well re-cemented together so that no audible pops are detected, the master must have broken in at least seven places at the beginnings of various shots (original splices presumably having severed, and frames of silence lost at the beginning of each scene), with the result that the film grows more and more progressively out of sync starting from about a quarter of the way along, placing Murray’s extended bedtime story several seconds out of sync by the end of the film. I and another poster on YouTube have expended considerable time to repair the gaps and restore the film to proper synchronization. The current YouTube resync came out about as good as my own, so I let such video stand for itself in the embed below.

Terrytoons was reasonably quick to follow with its own tribute to over-the-air broadcasting, Radio Girl (Terrytoons/Educational, 4/17/32) again spends approximately a third of its running length in a parody of the morning exercise program. Inside the studio, we see a behing-the-scenes glimpse of the healthy specimen who is providing the instruction – a 70 year old bewhiskered geezer in a wheelchair! His listeners are as avid fitness buffs as those of Fleischer’s broadcast. Atop a building, a cock rooster from a metal weather vane comes to life and performs hops from one directional pointer of the vane to another. A dog re-barks the musical rhythm count of the broadcast to a quartet of cats on a fence who perform the stretching exercise. A waterfront skyline view of the city depicts every tall tower and skyscraper of the city joining in the rhythmic stretching, also accompanied by a rising and lowering drawbridge, and a hopping sun at the horizon level. At the stock exchange, a bull and a bear ride a teeter-totter, using a ticker-tape machine as a fulcrum. Each one rises and falls to the verbal instructions, “Up. Down.” In perhaps the best line of the film, the elderly instructor breaks off from his counting, and states as if ad-libbing, “Is this a racket, I ask you?” A further shot at the stock exchange shows a squad of mice filing away transaction orders in a large filing cabinet bearing index tabs reading “Poor fish”. The show host appropriately changes the melody of his instruction to a parady of the old sing-song “Hi Lee, Hi Lo”, reworded, “Buy low. Sell High.” Back at the studio, as he rocks on a pair of crutches, the instructor tells the listeners to “Open the window, and throw out your chest.” The listeners get the wrong idea, and begin ejecting from every window in town their respective chests of drawers.

Terrytoons was reasonably quick to follow with its own tribute to over-the-air broadcasting, Radio Girl (Terrytoons/Educational, 4/17/32) again spends approximately a third of its running length in a parody of the morning exercise program. Inside the studio, we see a behing-the-scenes glimpse of the healthy specimen who is providing the instruction – a 70 year old bewhiskered geezer in a wheelchair! His listeners are as avid fitness buffs as those of Fleischer’s broadcast. Atop a building, a cock rooster from a metal weather vane comes to life and performs hops from one directional pointer of the vane to another. A dog re-barks the musical rhythm count of the broadcast to a quartet of cats on a fence who perform the stretching exercise. A waterfront skyline view of the city depicts every tall tower and skyscraper of the city joining in the rhythmic stretching, also accompanied by a rising and lowering drawbridge, and a hopping sun at the horizon level. At the stock exchange, a bull and a bear ride a teeter-totter, using a ticker-tape machine as a fulcrum. Each one rises and falls to the verbal instructions, “Up. Down.” In perhaps the best line of the film, the elderly instructor breaks off from his counting, and states as if ad-libbing, “Is this a racket, I ask you?” A further shot at the stock exchange shows a squad of mice filing away transaction orders in a large filing cabinet bearing index tabs reading “Poor fish”. The show host appropriately changes the melody of his instruction to a parady of the old sing-song “Hi Lee, Hi Lo”, reworded, “Buy low. Sell High.” Back at the studio, as he rocks on a pair of crutches, the instructor tells the listeners to “Open the window, and throw out your chest.” The listeners get the wrong idea, and begin ejecting from every window in town their respective chests of drawers.

On board an ocean liner crossing the sea, the return to commands of “Up. Down”, is responded to by a group of seasick passengers, heaving their internal lunches over the rail. At another location, a tipsy drunkard is returning home at the crack of dawn, witnessing from his intoxication the ground and a lamppost rising and falling (much in the manner of the more famous sequence from Harman-Ising’s “You Don’t Know What You’re Doin’”). He reaches his door, only to be clunked on the head by his wife’s rolling pin, and stays “Down.” Time being up for the program, the old man is yanked away from the studio microphone by a vaudeville theatre “hook”. Then, a dignified announcer enters, and asks the listeners to let them know how you liked the program. The audience respnds, by tossing tomatoes into the horns of their radio sets, which all emerge out the microphone of the announcer to pepper him in the face. “Thank you”, he politely responds, as a last tomato knocks him out of the room.

On board an ocean liner crossing the sea, the return to commands of “Up. Down”, is responded to by a group of seasick passengers, heaving their internal lunches over the rail. At another location, a tipsy drunkard is returning home at the crack of dawn, witnessing from his intoxication the ground and a lamppost rising and falling (much in the manner of the more famous sequence from Harman-Ising’s “You Don’t Know What You’re Doin’”). He reaches his door, only to be clunked on the head by his wife’s rolling pin, and stays “Down.” Time being up for the program, the old man is yanked away from the studio microphone by a vaudeville theatre “hook”. Then, a dignified announcer enters, and asks the listeners to let them know how you liked the program. The audience respnds, by tossing tomatoes into the horns of their radio sets, which all emerge out the microphone of the announcer to pepper him in the face. “Thank you”, he politely responds, as a last tomato knocks him out of the room.

Warner Brothers gets into the same vibe with I’ve Got to Sing a Torch Song (Merrie Melodies (B&W), 9/23/33 – Tom Palmer, dir.). This odd cartoon, the only directing credit for Palmer at WB, feels almost as if it should have been animated at any studio in Hollywood other than Warner, or of course Disney. It has a different feel that perhaps most closely resembles Charles Mintz, or the studio with which Palmer would next strike up an association – Van Buren. Another random spot gag tribute to the universal appeal of radio, it includes strange concepts such as, instead of introducing a montage of international gags with a visual reference to “third world” countries, for no apparent reason showing us repeated views of seven globes spinning in space – please explain, if anyone can. The broadcast day of course begins again with the exercise program, except in this case, the listening audience has no idea that the program is not even being presided over by a live instructor. Instead, it is one of those phonograph records I was telling you about, being played by a studio executive who has fallen fast asleep during its play. We see in a typical American home an unflattering view of a whole family doing bending exercises in only their underwear, wth heavy emphasis on their overweight derrieres. Another home shows us a man who appears to be pulling upon ropes held back by suspended weights – but in actuality, the cords are the laces of his hefty wife’s garters, which he is desperately but unsuccessfully trying to tighten around her. Another man rhythmically rocks back and forth in his own form of exercise – rocking with each outstretched arm twin cradles for two pairs of infant twins (their names on the cradles read “Topsy and Eva” – references to characters of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, and “Mike and Ike” – reference to a well known candy, still in production to ths day). Another stock market reference appears with a stockbroker doing hus “up/down” bobbing while reading the latest numbers off the ticker tape. We add a few international listeners – first, Mussolini of Italy, riding atop a hobby horse and performing “Il Duce” hand salutes to the announcer’s cues. Then, what appears to be George Bernard Shaw, for some reason getting in punching-bag training upon a bag painted to resemble the globe, only to have the bag smack him in the face. And the film continues into the broadcast day, getting ,ore bizarre by the minute, and climaxing with the title number performed by the impossible trio of Greta Garbo, Zasu Pitts, and Mae West!

Warner Brothers gets into the same vibe with I’ve Got to Sing a Torch Song (Merrie Melodies (B&W), 9/23/33 – Tom Palmer, dir.). This odd cartoon, the only directing credit for Palmer at WB, feels almost as if it should have been animated at any studio in Hollywood other than Warner, or of course Disney. It has a different feel that perhaps most closely resembles Charles Mintz, or the studio with which Palmer would next strike up an association – Van Buren. Another random spot gag tribute to the universal appeal of radio, it includes strange concepts such as, instead of introducing a montage of international gags with a visual reference to “third world” countries, for no apparent reason showing us repeated views of seven globes spinning in space – please explain, if anyone can. The broadcast day of course begins again with the exercise program, except in this case, the listening audience has no idea that the program is not even being presided over by a live instructor. Instead, it is one of those phonograph records I was telling you about, being played by a studio executive who has fallen fast asleep during its play. We see in a typical American home an unflattering view of a whole family doing bending exercises in only their underwear, wth heavy emphasis on their overweight derrieres. Another home shows us a man who appears to be pulling upon ropes held back by suspended weights – but in actuality, the cords are the laces of his hefty wife’s garters, which he is desperately but unsuccessfully trying to tighten around her. Another man rhythmically rocks back and forth in his own form of exercise – rocking with each outstretched arm twin cradles for two pairs of infant twins (their names on the cradles read “Topsy and Eva” – references to characters of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, and “Mike and Ike” – reference to a well known candy, still in production to ths day). Another stock market reference appears with a stockbroker doing hus “up/down” bobbing while reading the latest numbers off the ticker tape. We add a few international listeners – first, Mussolini of Italy, riding atop a hobby horse and performing “Il Duce” hand salutes to the announcer’s cues. Then, what appears to be George Bernard Shaw, for some reason getting in punching-bag training upon a bag painted to resemble the globe, only to have the bag smack him in the face. And the film continues into the broadcast day, getting ,ore bizarre by the minute, and climaxing with the title number performed by the impossible trio of Greta Garbo, Zasu Pitts, and Mae West!

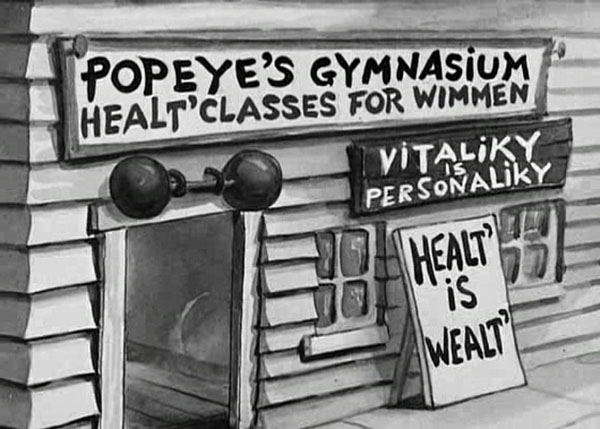

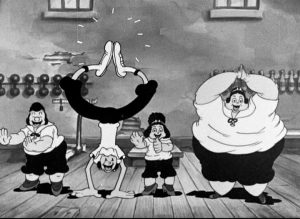

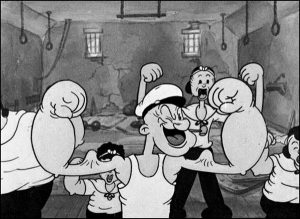

Vim, Vigor, and Vitaliky (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 1/3/36 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.), takes the field of exercise out of the domestic parlor, and into more formal surroundings. Popeye, who seems to have finally realized that his superhuman (if not visibly buffed) muscles give him sex appeal extending beyond the eyes of scrawny Olive Oyl, has embarked upon a new business venture – a women’s gymnasium. He promotes it with advertsising slogans. “Vitaliky is personaliky. Helth is welth.” (At least one blogger marvelled at the fact that he is somehow able to spell “Gymnasium” right!). Next door, Bluto runs a cabaret, where business is dying, with all the frails heading for Popeye’s competing establishment. He attempts to block Olive’s entrance into the gym, telling her, “Gettin’ healthy is the bunk. C’mon with me and have a good time.” “Sc-ram”, replies Olive, using her extended skinny limbs to step right over Bluto into the door. As Olive joins Popeye’s morning calisthenics session, Bluto gets an idea to upset the apple cart, and invasdes the empty ladies’ locker room. There, he acquires an extra-large size of the class’s exercise uniform, and mixes up in a sink a strong cup of shaving lather. Acquiring a razor, for once he manages to give himself a fairly clean shave in a mirror, then produces from nowhere a half-wig of bang-curls to hang from his own hairy head – to impersonate a woman. Bluto enters the gym, stating to Popeye “her” desire tio join the class. Popeye marvels at the already intensely-developed size of Bluto’s forearm muscles. “Ya looks pretty strong,” he observes. “I’m even stronger than you”, Bluto claims in fake effeminate giggle. “There ain’t any woman that’s a better man than I am”, says Popeye.

Vim, Vigor, and Vitaliky (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 1/3/36 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.), takes the field of exercise out of the domestic parlor, and into more formal surroundings. Popeye, who seems to have finally realized that his superhuman (if not visibly buffed) muscles give him sex appeal extending beyond the eyes of scrawny Olive Oyl, has embarked upon a new business venture – a women’s gymnasium. He promotes it with advertsising slogans. “Vitaliky is personaliky. Helth is welth.” (At least one blogger marvelled at the fact that he is somehow able to spell “Gymnasium” right!). Next door, Bluto runs a cabaret, where business is dying, with all the frails heading for Popeye’s competing establishment. He attempts to block Olive’s entrance into the gym, telling her, “Gettin’ healthy is the bunk. C’mon with me and have a good time.” “Sc-ram”, replies Olive, using her extended skinny limbs to step right over Bluto into the door. As Olive joins Popeye’s morning calisthenics session, Bluto gets an idea to upset the apple cart, and invasdes the empty ladies’ locker room. There, he acquires an extra-large size of the class’s exercise uniform, and mixes up in a sink a strong cup of shaving lather. Acquiring a razor, for once he manages to give himself a fairly clean shave in a mirror, then produces from nowhere a half-wig of bang-curls to hang from his own hairy head – to impersonate a woman. Bluto enters the gym, stating to Popeye “her” desire tio join the class. Popeye marvels at the already intensely-developed size of Bluto’s forearm muscles. “Ya looks pretty strong,” he observes. “I’m even stronger than you”, Bluto claims in fake effeminate giggle. “There ain’t any woman that’s a better man than I am”, says Popeye.

Of course, another test of feats of strength ensues. Bluto perfoms several chin-ups from a bar. Popeye’s feet never leave the floor, as he merely compresses the steel rods holding the bar in place, casing the bar to descend to his chin. Bluro’s somersault flips from a trapeze bar are matched by Popeye swinging no-hands style by his nose. Popeye alse excels at rope climbing, pulling himself up by one arm, and using the other to bend the rope under himself to provide his rear-end with a place to sit. Finally, Bluto starts flinging a medicine ball around. As Popeye takes pounding blows to the chest, he cautions, “Ya knows I can’t be rough with a woman. Take it easy.” This is all the encouragement Bluto needs to give his strongest throw, flattening Popeye. Bluto adds crowning blows with weight rope-pulls, pulling the weights completely off the pulleys and bashing them over Popeye’s head. “He can’t take it, girls”, Bluto says to the astounded class. Bluto passes under a conveniently-placed hook which happens to be dangling from the ceiling, snagging his wig off his head in the process. “It’s a man”, cries Olive. She tells Bluti to go, but Bluto grabs her outstetched hand and tries to drag her back to the cabaret. Olive’s feet catch on s pair of exercise rings suspended from the ceiling, and Bluto plays tug of war, stretching Olive notably in attempt to jar her feet loose. Popeye finally comes to, realizing “She’s a he!”. and rolls a dimbbell across the floor to the opposite wall, where it rolls up an exercise mat to collide with the bottom of a firsf aid cabinet, inside of which is – Popeye’s spinach, which neatly rolls back to him. The climactic fight is on. Popeye swings from a trapeze, grabbing Bluto away from Olive. He socks a large punching bag into Bluto, deflating it and covering Bluto in sawdust. Bluto pitches Indian clubs at Popeye, but Popeye neatly catches and returns each club to bounce off Bluto’s head and land in a neat row back in the wall rack. Popeye yells, “Get up, ya woman imperculator”, and gives Bluto a final blow, sending him soaring throgh a basketball net for a final two points. The class peacefully resumes. “The way to be wealthy is always keep healthy with Popeye the sailor man”, they sing for the iris out.

Of course, another test of feats of strength ensues. Bluto perfoms several chin-ups from a bar. Popeye’s feet never leave the floor, as he merely compresses the steel rods holding the bar in place, casing the bar to descend to his chin. Bluro’s somersault flips from a trapeze bar are matched by Popeye swinging no-hands style by his nose. Popeye alse excels at rope climbing, pulling himself up by one arm, and using the other to bend the rope under himself to provide his rear-end with a place to sit. Finally, Bluto starts flinging a medicine ball around. As Popeye takes pounding blows to the chest, he cautions, “Ya knows I can’t be rough with a woman. Take it easy.” This is all the encouragement Bluto needs to give his strongest throw, flattening Popeye. Bluto adds crowning blows with weight rope-pulls, pulling the weights completely off the pulleys and bashing them over Popeye’s head. “He can’t take it, girls”, Bluto says to the astounded class. Bluto passes under a conveniently-placed hook which happens to be dangling from the ceiling, snagging his wig off his head in the process. “It’s a man”, cries Olive. She tells Bluti to go, but Bluto grabs her outstetched hand and tries to drag her back to the cabaret. Olive’s feet catch on s pair of exercise rings suspended from the ceiling, and Bluto plays tug of war, stretching Olive notably in attempt to jar her feet loose. Popeye finally comes to, realizing “She’s a he!”. and rolls a dimbbell across the floor to the opposite wall, where it rolls up an exercise mat to collide with the bottom of a firsf aid cabinet, inside of which is – Popeye’s spinach, which neatly rolls back to him. The climactic fight is on. Popeye swings from a trapeze, grabbing Bluto away from Olive. He socks a large punching bag into Bluto, deflating it and covering Bluto in sawdust. Bluto pitches Indian clubs at Popeye, but Popeye neatly catches and returns each club to bounce off Bluto’s head and land in a neat row back in the wall rack. Popeye yells, “Get up, ya woman imperculator”, and gives Bluto a final blow, sending him soaring throgh a basketball net for a final two points. The class peacefully resumes. “The way to be wealthy is always keep healthy with Popeye the sailor man”, they sing for the iris out.

Betty Boop and Little Jimmy (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 3/26/36 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Hicks Lokey/Myron Waldman, anim.). Little Jimmy was the third newspaper character to be given a tryout in Betty Boop productions of this period (the others being in Betty Boop and Henry, the Funniest Living American and Betty Boop and the Little King) – all of which proved unsuccessful and less than memorable. Little Jimmy garnered his name from cartoonist Jimmy Swinnerton (also the creator of the “Canyon Kiddies” series which produced the graphic inspiration for Chuck Jones’s Mighty Hunters for Warner in 1940). The Little Jimmy strip was long running in the King Features Syndicate, lasting from 1904 through 1958. As I would still have been in a cradle during its final year of run, I missed the strip altogether, and myself knew nothing of its legacy until researching this article, so I can’t speak for the strip’s popularity or quality. Suffice it to say that the character makes no stunning breakthroughs from his entry into a new medium through this film, and sadly comes across bland and nearly without personality.

Betty Boop and Little Jimmy (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 3/26/36 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Hicks Lokey/Myron Waldman, anim.). Little Jimmy was the third newspaper character to be given a tryout in Betty Boop productions of this period (the others being in Betty Boop and Henry, the Funniest Living American and Betty Boop and the Little King) – all of which proved unsuccessful and less than memorable. Little Jimmy garnered his name from cartoonist Jimmy Swinnerton (also the creator of the “Canyon Kiddies” series which produced the graphic inspiration for Chuck Jones’s Mighty Hunters for Warner in 1940). The Little Jimmy strip was long running in the King Features Syndicate, lasting from 1904 through 1958. As I would still have been in a cradle during its final year of run, I missed the strip altogether, and myself knew nothing of its legacy until researching this article, so I can’t speak for the strip’s popularity or quality. Suffice it to say that the character makes no stunning breakthroughs from his entry into a new medium through this film, and sadly comes across bland and nearly without personality.

By the time Jimmy finds his way back to Boop’s attic, he breaks the disappointing news to Betty that he “couldn’t find a musician.” Fortunately by this point, he’s solved the problem himself, by tripping over the machine’s electric cord and disconnecting it from its power source. As the machimery slows and stops, Betty is revealed to have been over-reduced to pencil-thin skeletal form. As Jimmy presents her with a mirror to view herself, Betty breaks out into hystrical laughter at the sight. Jimmy doubles up with laughter also, and adds a line to Betty’s original song, expressing a completely unexplainable and mysteriously “convenient” law of cartoon phusics – laughter is allegedly a cure for thinness, and makes you grow fat. Betty and Jimmy continue to laugh without control, contagiously spreading laughter into various inanimate objects within the attic, until the two of them are rolling about the floorr as inflated roly-polys, for the iris out. So what’s next? Another dose of the exercise belt machine, I suppose, in hopes they time it right in deciding when to shut it off. This could take a while.

More Pep (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 6/19/36 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Dave Hoffman/Thomas Johnson, anim.). One of the many later Boop titles to “feature” a supporting player in essentially a starring role, this cartoon is billed as a feature vehicle for Betty’s puppy, Pudgy. However, the pup, usually mild-mannered and anything other than a star-struck show off, curiously finds himself in an unexpected situation. In a return to the format of Fleischer’s “Out of the Inkwell” cartoons of the teens and twenties, the hand (supposedly of Max) paints in a background of a theatrical stage, including props for a daredevil act. An announcer (certainly not Max himself) provides the alleged voice of the studio head, delivering a high-intensity introduction in the manner of a circus ringmaster, describing the feat to be performed by “that daring, breathtaking, exciting exponent of wizardry in the air” – Pudgy! On the stage, Pudgy is to climb a platform, leap from it onto a trampoline, bounce onto a slide and perform a double loop-de-loop, then sail through a ring stuffed with razor-sharp knives without being injured. What did Pudgy do to Max to deserve this treatment? Introductions completed, the spotlight and camera turn to the stage wings, from which emerges out star – disinterested, drooping, and half-asleep, in no mood to be a daredevil. His eyelids drop and he attempts to curl up for a siesta twice before even crossinh the stage, and has to be prodded on by the insistent call of Max. He finally mounts the first platform, but his eyelids sag again. He now views the trampoline as a perfect hammock, and softly plops himself into its center, nodding off into a sound sleep.

Not exactly what this Boop cartoon is advocating…. but Kelloggs PEP had been around since 1923, a long-running rival to Wheaties.

Porky’s Pet (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky Pig), 7/11/36 – Jack King, dir.) provides some of animation’s first glimpses in support of the opposing position that there is little or no purpose in spending the day watching what you eat – just close your eyes, and swallow it. The vehicle for this philosophy is a pet ostrich (Lulu), which Porky Pig uses as a performing partner in a vaudeville act. He receives a telegram of an opening in a show, but must show up in New York to claim the job. This requires that he and the ostrich obtain passage at the local railway terminal, but the conductor insists, “No buzzards allowed on this train”. Porky eventually smuggles the bird aboard by having him wait further down the tracks for the train to come, then painfully snagging the bird’s neck with his hand outstretched from the train window as the train passes. Once the bird is inside the train, director King presents a series of shots depicting that the ostrich eats anything, as she devours the wig from a bald man’s head, a child’s toy flying airplane which cause her head to whiz around as if itself in flight, and a musical concertina that expands and contracts its bellows inside her neck once swallowed, producing notes sure to rouse the attention of the conductor. From these simple, almost throwaway ideas, King would later fashion the nucleus for an extended and elaborately-animated plot for the first series-banner Donald Duck solo film for Disney and RKO in 1937, to be discussed next week, and also provide inspiration for a subsequent Friz Freleng Technicolor outing for Warner in similar vein.

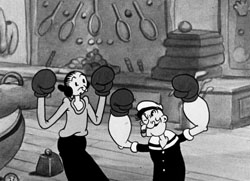

Never Kick a Woman (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 8/28/36 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.). A mere few months after Popeye’s gymnastics experience, under the same directors and animators as the previous episode, Popeye is giving instruction again, this time in exclusive lessons to Olive Oyl on the healthy art of self-defense. String-bean Olive isn’t exactly built for the task of her own preservation, but they see a new sporting-goods store where a well-developed (in more ways than one!) blonde female boxer demonstrates her stuff with a punching roly-poly in the store window, then hangs out signs inviting the public to come in and try the equipment. In an original song, “Learn the Art of Self-Defense”, Popeye demonstrates various swings to win any argument, causing Olive to reflexively “feint” her way backwards into the store. There, they (or perhaps it is only Popeye to whom it is directed) are greeted by the boxer, who has the spoken demeanor of Mae West. To Popeye, she comments in admiration, “You’re not an oil painting, but you’re a fascinatin’ monster.” “Get her”, Olive jealously reacts. “I’ll bet she says that to all the fascinatin’ monsters”, responds Popeye. Popeye sets Olive up with an inverted punching bag, suspended atop a spring-based pole mounted in the floor. Popeye demonstrates a series of blows on the bag, topping it with his “twisker punch”. The bag springs back, getting one blow in on Popeye. “That didn’t count”, Popeye announces in disclaimer. Olive steps up, scared to death of the contraption, and gives it a hesitant nudge, quickly hiding her face behind her boxing gloves. The bag bobbles back into position without causing any damage. Olive begins to rise to the occasion, and with a girlish giggle, taps the bag again, playfully calling out, “Bang.” This time, the back socks her back, squarely on the jaw. As Olive attempts to fight back, her rubbery limbs tying themselves into pretzel knots, the lady boxer breaks into laughter at Olive’s ineptness – then, considering Olive no competition, begins an open flirtation with Popeye. “Why don’t’cha come up and see me sometime?” “I’m practically there”, responds a blushing Popeye.

Never Kick a Woman (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 8/28/36 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/Roland Crandall, anim.). A mere few months after Popeye’s gymnastics experience, under the same directors and animators as the previous episode, Popeye is giving instruction again, this time in exclusive lessons to Olive Oyl on the healthy art of self-defense. String-bean Olive isn’t exactly built for the task of her own preservation, but they see a new sporting-goods store where a well-developed (in more ways than one!) blonde female boxer demonstrates her stuff with a punching roly-poly in the store window, then hangs out signs inviting the public to come in and try the equipment. In an original song, “Learn the Art of Self-Defense”, Popeye demonstrates various swings to win any argument, causing Olive to reflexively “feint” her way backwards into the store. There, they (or perhaps it is only Popeye to whom it is directed) are greeted by the boxer, who has the spoken demeanor of Mae West. To Popeye, she comments in admiration, “You’re not an oil painting, but you’re a fascinatin’ monster.” “Get her”, Olive jealously reacts. “I’ll bet she says that to all the fascinatin’ monsters”, responds Popeye. Popeye sets Olive up with an inverted punching bag, suspended atop a spring-based pole mounted in the floor. Popeye demonstrates a series of blows on the bag, topping it with his “twisker punch”. The bag springs back, getting one blow in on Popeye. “That didn’t count”, Popeye announces in disclaimer. Olive steps up, scared to death of the contraption, and gives it a hesitant nudge, quickly hiding her face behind her boxing gloves. The bag bobbles back into position without causing any damage. Olive begins to rise to the occasion, and with a girlish giggle, taps the bag again, playfully calling out, “Bang.” This time, the back socks her back, squarely on the jaw. As Olive attempts to fight back, her rubbery limbs tying themselves into pretzel knots, the lady boxer breaks into laughter at Olive’s ineptness – then, considering Olive no competition, begins an open flirtation with Popeye. “Why don’t’cha come up and see me sometime?” “I’m practically there”, responds a blushing Popeye.

Olive gets madder and madder, repeating each flirtation aloud, and finally socks the bag with enough impact to knock the sawdust out of it. Olive feels ready for a fray, and confronts Popeye to ignore the amazon and continue with her lessons. “He’s goin’ my way” says the boxer, tossing Popeye backwards over her shoulder, out of Olive’s reach. “Get the number of that truck”, replies Popeye as man in the middle. Confronting Olive the boxer says, “Take it easy, skinny, you’ll last longer”, as she dons her gloves and lands a blow to Olive’s nose. “Don’t call me skinny”, calls Olive, and a bell sounds from nowhere to begin round 1. Olive attempts to hold the boxer out of reach by extending one of her long, skinny arms against the boxer’s forehead. The pair lift a maneuver from the Three Stooges, as the boxer brings her fist down vertically upon Olive’s glove, but only succeeds in rotating olive’s arm like a propeller, causing her glove to come back down after one revolution upon the boxer’s head. “What happened?”. mutters a puzzled Olive. The boxer revives, and starts to connect with her blows. Olive takes a series of hits right in the face, each blow completely rearranging her hair, into Pocahontas braids, Marge Simpson bouffant, and Little Lulu spit-curls. Popeye is enjoying the spectacle. “Oh, boy, what a fight. C’mon, goils, mix it up!” Two more well placed blows leave Olive prone on the floor. The boxer returns to her overtures to Popeye, calling him “tall dark and handsome”. Popeye mutters. “I’m not so tall, but the rest of it goes” (a line that would be paraphrased later for “Aladdin and his Wonderful Lamp”). A bedraggled Olive crawls along the floor up to Popeye’s feet, and reaches out for a visible spinach can in Popeye’s hip pocket. Olive gets to consume the spinach, and fights again for her man. She is transformed into a howling, arch-backed cat, to commence a real “cat fight”. A short series of powerful blows sends the boxer into a spiral, and a final wallop lands her back in the store window, crumpled in a heap. “Nice work, Olive”, Popeye comments with approval. But Olive is not so forgiving, and pummels Popeye, too, finally causing his hat and pipe to be knocked off, landing upon her own head. Olive performs the final singing and pipe toot, as Popeye, realizing he deserved it, just weakly smiles.

Olive gets madder and madder, repeating each flirtation aloud, and finally socks the bag with enough impact to knock the sawdust out of it. Olive feels ready for a fray, and confronts Popeye to ignore the amazon and continue with her lessons. “He’s goin’ my way” says the boxer, tossing Popeye backwards over her shoulder, out of Olive’s reach. “Get the number of that truck”, replies Popeye as man in the middle. Confronting Olive the boxer says, “Take it easy, skinny, you’ll last longer”, as she dons her gloves and lands a blow to Olive’s nose. “Don’t call me skinny”, calls Olive, and a bell sounds from nowhere to begin round 1. Olive attempts to hold the boxer out of reach by extending one of her long, skinny arms against the boxer’s forehead. The pair lift a maneuver from the Three Stooges, as the boxer brings her fist down vertically upon Olive’s glove, but only succeeds in rotating olive’s arm like a propeller, causing her glove to come back down after one revolution upon the boxer’s head. “What happened?”. mutters a puzzled Olive. The boxer revives, and starts to connect with her blows. Olive takes a series of hits right in the face, each blow completely rearranging her hair, into Pocahontas braids, Marge Simpson bouffant, and Little Lulu spit-curls. Popeye is enjoying the spectacle. “Oh, boy, what a fight. C’mon, goils, mix it up!” Two more well placed blows leave Olive prone on the floor. The boxer returns to her overtures to Popeye, calling him “tall dark and handsome”. Popeye mutters. “I’m not so tall, but the rest of it goes” (a line that would be paraphrased later for “Aladdin and his Wonderful Lamp”). A bedraggled Olive crawls along the floor up to Popeye’s feet, and reaches out for a visible spinach can in Popeye’s hip pocket. Olive gets to consume the spinach, and fights again for her man. She is transformed into a howling, arch-backed cat, to commence a real “cat fight”. A short series of powerful blows sends the boxer into a spiral, and a final wallop lands her back in the store window, crumpled in a heap. “Nice work, Olive”, Popeye comments with approval. But Olive is not so forgiving, and pummels Popeye, too, finally causing his hat and pipe to be knocked off, landing upon her own head. Olive performs the final singing and pipe toot, as Popeye, realizing he deserved it, just weakly smiles.

Classes resume here again next week.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I have to say, your Animation Trails are going from strength to strength!

I guess most people today don’t realise that George Bernard Shaw was a great boxing enthusiast, having taken up the sport in his youth. (He really was as scrawny as he’s depicted in the cartoon, so I’m guessing… bantamweight?) In fact he was very close friends with world heavyweight champion Gene Tunney for many years. Sportswriters at the time were always cracking jokes about the well-read Tunney hanging out with eggheads like Shaw and Thornton Wilder, which was common knowledge then. The cartoon takes a well-placed jab at Shaw’s celebrated vanity by showing his room decorated with his own likeness, as well as a floral arrangement that he sent to himself.

“I’ve Got to Sing a Torch Song” is probably the only cartoon I’ve ever seen containing a caricature of Greta Garbo that didn’t make fun of her supposedly enormous feet.

I can’t help but wonder how much sexier the boxer in “Never Kick a Woman” would be if Grim Natwick had stayed at the studio.

The problem with Radio Riot isn’t missing frames from the soundtrack. Something went wrong when the track was reduced to 16mm or otherwise duplicated, such that the entire track runs a bit too fast. On my end I simply slowed down the track a little, which made it more or less properly in sync (bearing in mind the studio was still getting the hang of sound synchronization at this time). I could post my version if desired.

Doesn’t the singing fly sound just like Olive Oyl?

Another Talkartoon with a similar problem in the N.T.A. version I have is Teacher’s Pest, but in this case the sound begins drifting out of sync about a third of the way in and seems to increasingly speed up, making a corrected version difficult to achieve.

“I’ve Got to Sing a Torch Song” was not Tom Palmer’s only directing credit at Warners. He had one other, the first Buddy cartoon “Buddy’s Day Out.”

I’ve always viewed the seven spinning globes as radio dials.

“Cros Bingsby” in the bathtub with a microphone? Don’t try that at home.

Tom Palmer did two cartoons in his brief stay with Schlesinger – the other being BUDDY’S DAY OUT, which did Palmer’s resume no favors. Watching these two head-scratchers leaves no doubt about the reason for his quick exit to Van Beuren.

One fitness orientated castoon I hope you’ll look at is the 1953 Robert McKimson-directed Daffy Duck cartoon The Muscle Tussle.

Are you including cartoons that show exercise as part of the training regimen of professional athletes? In “Gym Gems” (Educational Pictures/Pat Sullivan, Felix the Cat, 8/8/26 — Otto Messmer, dir.), Felix finds himself at a boxer’s training camp; while in “The Rasslin’ Match” (Van Beuren/RKO, Amos and Andy, 5/1/34 — George Stallings, dir.), Andy prepares for his upcoming wrestling match against Bullneck Mooseface with a program of weight training, shadow boxing, and cross-country running under the tutelage of the mighty Brother Hercules.

I might possibly include one or two, but mostly, I’ll be saving the ones on dedicated prize fights for a possible trail on that genre of films in the future.

Excellent, educationally healthy article.

Gardner: Miscellaneous note to sport, but there’s a gag in “Radio Girl” cut for television, probably because toilet jokes were suggestively taboo for CBS: You can see it here, in a silent French home release: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ITGLdu4WBA

At 1:10, clothes are hopping up and down as a cat sits in a port-a-john. The cat gets freaked out at the clothes in rhythm, then runs off.

The early silent cartoon “The Phable of the Phat Woman” (International Film Service/Hearst-Vitagraph News Pictorial, 18/1/16 — Tom E. Powers, story; animated by Raoul Barre), just two and a half minutes long, deserves mention here. A corpulent woman steps on the scale and, alarmed at the result, embarks on a program of diet and exercise. We see her touching her toes, running, doing leg exercises while standing on her head, roasting in a sweat box, and turning down dessert at dinner. (All the while a number of little sprites in the foreground, representing “joy” and “gloom”, give an account of her changing moods.) At the end of three months, she weighs herself — and finds that she’s gained so much weight, the scale breaks. The film is in the collection of the Library of Congress, which has posted it online.

In “Irish Sweepstakes” (Terrytoons/Educational, 27/7/34 — Frank Moser and Paul Terry, dirs.), the horses prepare for the big race by getting in shape at the Training Camp. We see them using the rowing machine, pedalling a stationary tandem bicycle, working out with a punching bag, and skipping rope, none of which I ever would have expected racehorses to do. But when the moustachioed villain knocks out the favourite Danny Boy by putting sleeping powder in his oats, the hero rides his sweet Fanny’s ass — that is, his girlfriend’s donkey — to victory.