“Innocent until proven guilty” is a standard maxim of jurisprudence. Sometimes it takes a great deal of proving to convict a toon, and a great deal of effort after that to make the sentence stick. This week’s roster of line-mileage litigants chalk up a substantial score for the defense attorneys, and even some of the convictions entered on the books are followed by brief moments of escape, forcing authorities to round them up all over again. Perhaps the Toontown District Attorney’s office could use a bit of a political shake-up. (Can we get Wilby Daniels to run again, from the animated credits of The Shaggy D.A.?)

Speaking of the Weather (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 9/4/37 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) is presented out of chronological sequence, to pair up with its subsequent reworking by Bob Clampett discussed below. A drug store’s magazine rack comes to life, spotlighting many radio and film caricatures as well as an array of newcomers from the covers of the pulp publications. Amidst various spot gags and musical production numbers, a thug from “Gang” magazine attempts to open a safe upon the cover of a publication on Wall Street with a blowtorch, but is stopped by Charlie Chan from the cover of Detective magazine. Playing cleverly upon the name of a real publication, the police obtain an admission of guilt from the thug on the cover of “True Confessions” magazine – a publication which actually dealt with romantic confessions and scandal, not crimes. The prisoner is brought up before the cover of “Judge” magazine (a humor magazine of the period, with a reputation for political cartoons). Based upon the confession, the judge on the cover sentences the hoodlum to confinement in the next magazine on the rack – “LIFE”, whose cover depicts a barred jail cell window in a rock wall. The prisoner struggles against the bars to no avail, then gets an idea. Stepping back from the bars, the prisoner disappears from camera view, and apparently travels inside the pages of the magazines to another cover a few publications down the rack. This cover depicts an identical jail cell, but from another window. The thug is now able to easily bend the iron bars and squeeze his way out the window – as this is the cover of “Liberty” magazine (a general interest magazine published from 1924 to 1950). It takes everyone from the boy scouts, to the Thin Man and Asta (from the William Powell pictures for MGM), to a tripping by the humongous feet of Greta Garbo, to land the thug upon the playing surface of the drug store’s pinball machine (animation essentially recycled from Sunday Fo To Meetin’ Time, reviewed last week), and finally bounced by the bumpers onto an actual hardbound novel which was made into a feature, “Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing”.

Speaking of the Weather (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 9/4/37 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) is presented out of chronological sequence, to pair up with its subsequent reworking by Bob Clampett discussed below. A drug store’s magazine rack comes to life, spotlighting many radio and film caricatures as well as an array of newcomers from the covers of the pulp publications. Amidst various spot gags and musical production numbers, a thug from “Gang” magazine attempts to open a safe upon the cover of a publication on Wall Street with a blowtorch, but is stopped by Charlie Chan from the cover of Detective magazine. Playing cleverly upon the name of a real publication, the police obtain an admission of guilt from the thug on the cover of “True Confessions” magazine – a publication which actually dealt with romantic confessions and scandal, not crimes. The prisoner is brought up before the cover of “Judge” magazine (a humor magazine of the period, with a reputation for political cartoons). Based upon the confession, the judge on the cover sentences the hoodlum to confinement in the next magazine on the rack – “LIFE”, whose cover depicts a barred jail cell window in a rock wall. The prisoner struggles against the bars to no avail, then gets an idea. Stepping back from the bars, the prisoner disappears from camera view, and apparently travels inside the pages of the magazines to another cover a few publications down the rack. This cover depicts an identical jail cell, but from another window. The thug is now able to easily bend the iron bars and squeeze his way out the window – as this is the cover of “Liberty” magazine (a general interest magazine published from 1924 to 1950). It takes everyone from the boy scouts, to the Thin Man and Asta (from the William Powell pictures for MGM), to a tripping by the humongous feet of Greta Garbo, to land the thug upon the playing surface of the drug store’s pinball machine (animation essentially recycled from Sunday Fo To Meetin’ Time, reviewed last week), and finally bounced by the bumpers onto an actual hardbound novel which was made into a feature, “Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing”.

Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow (Terrytoons/Fox, 7/22/38 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.), may mark one of animation’s only prosecutions on a count of arson. Our title character is brought up on charges for starting the historic fire that devastated early Chicago (which had recently been the subject of a major feature from Fox, the distributors of the cartoon, “In Old Chicago” starring Tyrone Power, Alice Faye, and Don Ameche – if MGM could devastate San Francisco with an earthquake, Fox could bring down Chicago in a blaze). The cow admits under cross-examination to having seen the lantern that legendarily ignited the inferno. She tearfully confesses in her Irish brogue that, while helping Mrs. O’Leary with washday chores in the barn, a large bumblebee flew in the window and menaced her. The lantern being the only sizeable object nearby to use as a weapon, the cow grabs the lantern up, and flings it at the bee. Its kerosene spills, setting the hay and the barn alight. Grabbing up the lantern, the cow races outside, as flames shoot out the structure’s windows and roof. With no fire alarm around, the cow improvises her own, making siren sounds with her large mouth, her tongue whirling like the internal mechanisms of such a device. The next several minutes lapse into a typical but rapidly timed epic of animated fire fighting, with personified flames chasing the fire fighters and turning hoses on them, ladders that won’t reach, hydrants that won’t squirt water (a fireman’s call for water is answered by six buckets being dumped out upon him from a boarding house’s windows), daring escapes across moving jets of water from the next building, and other fire fighters chopping every item rescued from the homes with their axes. The cow is spotted on the street by the local police, and lassoed with a rope, then dragged into custody inside a “Black Maria” paddy wagon. The scene dissolves back to the courtroom, where the cow pounds the desk for emphasis as she insists that what she’s said is the honest truth. Her last pound knocks over the lantern, setting the courtroom on fire. “Glory be! I’ve done it again”, the cow says, her mouth again turning into a siren as the scene irises out.

Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow (Terrytoons/Fox, 7/22/38 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.), may mark one of animation’s only prosecutions on a count of arson. Our title character is brought up on charges for starting the historic fire that devastated early Chicago (which had recently been the subject of a major feature from Fox, the distributors of the cartoon, “In Old Chicago” starring Tyrone Power, Alice Faye, and Don Ameche – if MGM could devastate San Francisco with an earthquake, Fox could bring down Chicago in a blaze). The cow admits under cross-examination to having seen the lantern that legendarily ignited the inferno. She tearfully confesses in her Irish brogue that, while helping Mrs. O’Leary with washday chores in the barn, a large bumblebee flew in the window and menaced her. The lantern being the only sizeable object nearby to use as a weapon, the cow grabs the lantern up, and flings it at the bee. Its kerosene spills, setting the hay and the barn alight. Grabbing up the lantern, the cow races outside, as flames shoot out the structure’s windows and roof. With no fire alarm around, the cow improvises her own, making siren sounds with her large mouth, her tongue whirling like the internal mechanisms of such a device. The next several minutes lapse into a typical but rapidly timed epic of animated fire fighting, with personified flames chasing the fire fighters and turning hoses on them, ladders that won’t reach, hydrants that won’t squirt water (a fireman’s call for water is answered by six buckets being dumped out upon him from a boarding house’s windows), daring escapes across moving jets of water from the next building, and other fire fighters chopping every item rescued from the homes with their axes. The cow is spotted on the street by the local police, and lassoed with a rope, then dragged into custody inside a “Black Maria” paddy wagon. The scene dissolves back to the courtroom, where the cow pounds the desk for emphasis as she insists that what she’s said is the honest truth. Her last pound knocks over the lantern, setting the courtroom on fire. “Glory be! I’ve done it again”, the cow says, her mouth again turning into a siren as the scene irises out.

Frozen Feet (Terrytoons/Fox (Phoney Baloney), 2/24/39 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – I believe this was the second appearance of Phoney Baloney – a tall-tale telling Irishman whose exotic exploits rival the “whoppers” of Willie Whopper or Baron Munchausen. Phoney had the distinction of being the only Terrytoons character besides Farmer Al Falfa discontinued from production for a time following the 1930’s, then reintroduced without change for several more adventures in Technicolor in the mid 1950’s.

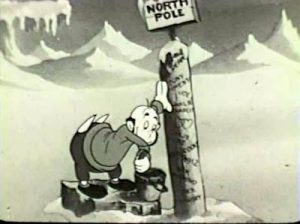

No complete print of this film has as yet surfaced, and it is obvious from the abrupt start of the CBS edit that we are entering right in the middle of things. So a little surmising as to what is probably missing is in order. From the continuity of the last sequences of the episode, it appears that Phoney’s tale of woe begins with a shot of him floating down an icy river, imprisoned except for his head in a large frozen ice cube. Breaking the fourth wall, Phoney speaks directly to the audience as first person narrator, informing us of how he came to be in this predicament. For reasons unknown, the adventurous spirit of Phoney has caused him to take on a daring and perilous challenge – to be the first person to reach the North Pole, and properly paint it in the red and white stripes of a barber pole! For this purpose, Phoney acquires a ship, complete with a first and second cook – one stereotypic black, the other stereotypic Chinese. (It is possible the presence of these characters accounts for the lopping off of one or two minutes of the beginning of this film. Then again, however, so much of them still remains in the present edit which couldn’t be cut around and leave a cognizable storyline, that it is just possible the omitted scenes were no worse than what still exists, and that the cut was made purely for time.) The CBS print curs directly into one of Phoney’s lines, as the ship arrives in the frozen North, and Phoney proudly holds up his paint bucket and brush to embark on his expedition to “paint the pole”. His descent of the gangplank is hastened by a sheet of ice that has quickly built up on the board, sliding him swiftly to the bottom, followed by the reluctant cooks. The Southern-dialect black cook suggests that no one would know if he chose not to paint the pole, causing Phoney to angrily remark, “That’s not the point!” The black cook continues to complain about getting his feet all cold and wet, until a living snowman taps him on the back, and asks “Are you from the South?” The cook takes off in fright, announcing, ‘Carolina, here I come”, and is never seen again. The Chinese cook continues to follow Phoney, until a road sign indicating proximity of the pole causes the cook to jump up and down in excitement – breaking through the ice below him to disappear into the waters below. Phoney pursues his mission alone, and, becoming hungry, hits upon an idea to blend inconspicuously among the local animal community. Spotting a walrus brushing his teeth (which turn out to be a removable set of tusk dentures), Phoney swipes the dentures away when the walrus’s back is turned, and inserts them into his own equally large jaws. Now appearing to be one of the communnity, Phoney is able to join another walrus at the ice’s edge for a little fishing, dropping in a line and quickly hooking a huge fish. To his surprise, his catch includes an added bonus, the Chinaman, whose voice can be heard from inside the fish. However, the Chinaman will have no part of the North, and, despite being pulled out by Phoney from the fish’s gullet, the Chinaman leaps right back in, freeing the fish and diving still encased in the fish’s stomach back into the icy waters.

No complete print of this film has as yet surfaced, and it is obvious from the abrupt start of the CBS edit that we are entering right in the middle of things. So a little surmising as to what is probably missing is in order. From the continuity of the last sequences of the episode, it appears that Phoney’s tale of woe begins with a shot of him floating down an icy river, imprisoned except for his head in a large frozen ice cube. Breaking the fourth wall, Phoney speaks directly to the audience as first person narrator, informing us of how he came to be in this predicament. For reasons unknown, the adventurous spirit of Phoney has caused him to take on a daring and perilous challenge – to be the first person to reach the North Pole, and properly paint it in the red and white stripes of a barber pole! For this purpose, Phoney acquires a ship, complete with a first and second cook – one stereotypic black, the other stereotypic Chinese. (It is possible the presence of these characters accounts for the lopping off of one or two minutes of the beginning of this film. Then again, however, so much of them still remains in the present edit which couldn’t be cut around and leave a cognizable storyline, that it is just possible the omitted scenes were no worse than what still exists, and that the cut was made purely for time.) The CBS print curs directly into one of Phoney’s lines, as the ship arrives in the frozen North, and Phoney proudly holds up his paint bucket and brush to embark on his expedition to “paint the pole”. His descent of the gangplank is hastened by a sheet of ice that has quickly built up on the board, sliding him swiftly to the bottom, followed by the reluctant cooks. The Southern-dialect black cook suggests that no one would know if he chose not to paint the pole, causing Phoney to angrily remark, “That’s not the point!” The black cook continues to complain about getting his feet all cold and wet, until a living snowman taps him on the back, and asks “Are you from the South?” The cook takes off in fright, announcing, ‘Carolina, here I come”, and is never seen again. The Chinese cook continues to follow Phoney, until a road sign indicating proximity of the pole causes the cook to jump up and down in excitement – breaking through the ice below him to disappear into the waters below. Phoney pursues his mission alone, and, becoming hungry, hits upon an idea to blend inconspicuously among the local animal community. Spotting a walrus brushing his teeth (which turn out to be a removable set of tusk dentures), Phoney swipes the dentures away when the walrus’s back is turned, and inserts them into his own equally large jaws. Now appearing to be one of the communnity, Phoney is able to join another walrus at the ice’s edge for a little fishing, dropping in a line and quickly hooking a huge fish. To his surprise, his catch includes an added bonus, the Chinaman, whose voice can be heard from inside the fish. However, the Chinaman will have no part of the North, and, despite being pulled out by Phoney from the fish’s gullet, the Chinaman leaps right back in, freeing the fish and diving still encased in the fish’s stomach back into the icy waters.

Phoney eventually gets to paint the pole, which can use a good covering, as its expanse bears the whittled etchings of many a name and various graffiti. (Print detail is poor on existing 16mm copies, but I believe one name etched on it is Charlie Chaplin – possibly a reference to his famous Yukon epic, The Gold Rush.) But just as Phoney is taking bows before the animal onlookers, the toothless walrus catches up with him, and hauls Phoney off to stand trial before a “Good Will Court”, where prosecutor and jury consist entirely of penguins. (Why do animators consistently insist on placing penguins at the North Pole?) The walrus shows the court his empty gums, and points at the tusks in Baloney’s mouth. Phoney fails to draw sympathry, falling prey to a temptation which testifying witnesses are frequently advised to avoid – making faces at an opponent in front of the jury. Phoney flips his false tusks around, so that one minute they are pointing up, then down, then one up and the other down. The irritated prosecutor points an incriminating flipper at him, and squawks accusations, then turns the case over to the jury. Entering an igloo jury room from one side, the penguins just as quickly exit out the other, and return to the court. (A budget cut makes for a curious continuity inconsistency, as 12 penguins are shown in the court scenes, yet only four enter and exit the igloo.) A unanimous guilty verdict allows the walrus to seize back his teeth, while Phoney declares, “You can’t do this to me.” Oh yes they can, as the animals surround him, fling him around, balance him on a seals nose, then flip him off the seal’s tail. Phoney is dunked into freezing ice water, emerging in the ice cube in which he began the picture, and cast off a cliff into the river. The scene dissolves back to the present, as Phoney, literally speaking from the theater screen, implores the audience to be so kind as to place a call to the Northwest Mounted Police. An excited lady in the audience rises from her seat, hurrying up the theater aisle to find a phone (with Phoney calling out directions to the booth from the screen). The mounties are called, and retrieve Phoney with a set of ice tongs mounted on an extender. As Phoney is towed back to civilization, he thanks the lady in the audience, and advises her to stay for the Bingo tonight – “I hope you win.”

Phoney eventually gets to paint the pole, which can use a good covering, as its expanse bears the whittled etchings of many a name and various graffiti. (Print detail is poor on existing 16mm copies, but I believe one name etched on it is Charlie Chaplin – possibly a reference to his famous Yukon epic, The Gold Rush.) But just as Phoney is taking bows before the animal onlookers, the toothless walrus catches up with him, and hauls Phoney off to stand trial before a “Good Will Court”, where prosecutor and jury consist entirely of penguins. (Why do animators consistently insist on placing penguins at the North Pole?) The walrus shows the court his empty gums, and points at the tusks in Baloney’s mouth. Phoney fails to draw sympathry, falling prey to a temptation which testifying witnesses are frequently advised to avoid – making faces at an opponent in front of the jury. Phoney flips his false tusks around, so that one minute they are pointing up, then down, then one up and the other down. The irritated prosecutor points an incriminating flipper at him, and squawks accusations, then turns the case over to the jury. Entering an igloo jury room from one side, the penguins just as quickly exit out the other, and return to the court. (A budget cut makes for a curious continuity inconsistency, as 12 penguins are shown in the court scenes, yet only four enter and exit the igloo.) A unanimous guilty verdict allows the walrus to seize back his teeth, while Phoney declares, “You can’t do this to me.” Oh yes they can, as the animals surround him, fling him around, balance him on a seals nose, then flip him off the seal’s tail. Phoney is dunked into freezing ice water, emerging in the ice cube in which he began the picture, and cast off a cliff into the river. The scene dissolves back to the present, as Phoney, literally speaking from the theater screen, implores the audience to be so kind as to place a call to the Northwest Mounted Police. An excited lady in the audience rises from her seat, hurrying up the theater aisle to find a phone (with Phoney calling out directions to the booth from the screen). The mounties are called, and retrieve Phoney with a set of ice tongs mounted on an extender. As Phoney is towed back to civilization, he thanks the lady in the audience, and advises her to stay for the Bingo tonight – “I hope you win.”

The Trial of Mr. Wolf (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 4/26/41 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – This may mark a rare instance where a Warner cartoon stole a basic plot premise from a Terrytoon! In 1938, Terry produced “The Wolf’s Side of the Story”, which (although falling short of inclusion in this article due to never making it to the courtroom, but instead having the wolf’s viewpoint told in the context of his statements to the police while being given the third degree) presents the Big Bad Wolf’s version of “Little Red Riding Hood”, painting himself as the innocent and Red and Granny as the real criminals. Friz’s version feels like it follows in a nearly identical vein, merely moving the action from the police station into the courtroom. (Notably, the Terrytoon may be said to have continued roots for a much later feature production, “Hoodwinked’, where the same idea of differing viewpoints of the “Red” story is built upon to present a multi-party array of perspectives for a full-blown police procedural.)

The Trial of Mr. Wolf (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 4/26/41 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – This may mark a rare instance where a Warner cartoon stole a basic plot premise from a Terrytoon! In 1938, Terry produced “The Wolf’s Side of the Story”, which (although falling short of inclusion in this article due to never making it to the courtroom, but instead having the wolf’s viewpoint told in the context of his statements to the police while being given the third degree) presents the Big Bad Wolf’s version of “Little Red Riding Hood”, painting himself as the innocent and Red and Granny as the real criminals. Friz’s version feels like it follows in a nearly identical vein, merely moving the action from the police station into the courtroom. (Notably, the Terrytoon may be said to have continued roots for a much later feature production, “Hoodwinked’, where the same idea of differing viewpoints of the “Red” story is built upon to present a multi-party array of perspectives for a full-blown police procedural.)

Friz may not be as familiar with courtroom procedure as some directors – or simply gets things hopelessly mixed-up in the opening sequences – as the film begins with a major continuity error. A wise old owl judge (whose robe bears advertising on the back like that of a prize fighter, reading “Supreme Court Golden Gloves 1901″) calls the case of “The Big Bad Wolf v. Little Red Riding Hood”. Normally, this would indicate from the order of the names presented that the wolf is the Plaintiff seeking damages, and Red the Defendant. This seems the case from the mood of the characters, as the Wolf is smiling and confident (Why not? His attorney has done a wonderful job in jury selection (Voir Dire), choosing a panel of all wolves and one skunk), while Red is somber, apologetic, and pleading her innocence. Then Friz confuses everything, by having the judge state to the wolf’s counsel, “Defense attorney. Present your case.” What is going on here? If he was a defense attorney, not only would the order of names on the case caption be wrong, but he would never get the chance to speak first, as that role always goes to the prosecutor! Your guess from here on is as good as mine whether the wolf is presenting a case for damages, or pleading his own defense. To make things even more strange, the case name would indicate that this is a mere civil suit for money, rather than a criminal prosecution – as the latter situation would normally be captioned “The People of v. The Big Bad Wolf”. If it is merely civil, then why hasn’t Red filed a cross-complaint (her own counter-claim) for money damages) against the wolf for what really happened? Friz, I hope you never had to sit for a bar examination. Your score would have been terrible.

Friz may not be as familiar with courtroom procedure as some directors – or simply gets things hopelessly mixed-up in the opening sequences – as the film begins with a major continuity error. A wise old owl judge (whose robe bears advertising on the back like that of a prize fighter, reading “Supreme Court Golden Gloves 1901″) calls the case of “The Big Bad Wolf v. Little Red Riding Hood”. Normally, this would indicate from the order of the names presented that the wolf is the Plaintiff seeking damages, and Red the Defendant. This seems the case from the mood of the characters, as the Wolf is smiling and confident (Why not? His attorney has done a wonderful job in jury selection (Voir Dire), choosing a panel of all wolves and one skunk), while Red is somber, apologetic, and pleading her innocence. Then Friz confuses everything, by having the judge state to the wolf’s counsel, “Defense attorney. Present your case.” What is going on here? If he was a defense attorney, not only would the order of names on the case caption be wrong, but he would never get the chance to speak first, as that role always goes to the prosecutor! Your guess from here on is as good as mine whether the wolf is presenting a case for damages, or pleading his own defense. To make things even more strange, the case name would indicate that this is a mere civil suit for money, rather than a criminal prosecution – as the latter situation would normally be captioned “The People of v. The Big Bad Wolf”. If it is merely civil, then why hasn’t Red filed a cross-complaint (her own counter-claim) for money damages) against the wolf for what really happened? Friz, I hope you never had to sit for a bar examination. Your score would have been terrible.

Anyway, the wolf, with such a favorably picked jury, receives immediate applause from his peers (despite the fact that in leaning over to take a bow, a knife, pistol, and hand grenade fall out of his vest pockets). The wolf’s attorney insists that Red has guilt written all over her face, and a view of Red depicts just that – the word penned in cursive handwriting everywhere. (Years later, Robert McKimson would embellish this gag in Daffy Duck’s The Super Snooper, having “The Body” attempt to cover up these telltale signs by applying a bit of facial powder.) Wolf’s counsel implores the jurors that they all know Red’s side of the story – now it’s time to hear the wolf’s side – and turns over the presentation to the wolf himself. (Another cinematic piece of procedural nonsense. Rarely if ever is a witness, especially in a civil case, permitted, or allowed by his/her own counsel, to testify in his/her own words. Proper procedure is question and answer between counsel and client or defendant – allowing the attorney to hopefully keep the scope of inquiry within the bounds of relevancy, and most importantly, keeping the witness in line so that he does not inadvertently blurt something out detrimental to his case – the proverbial situation of a “loose cannon”.)

Anyway, the wolf, with such a favorably picked jury, receives immediate applause from his peers (despite the fact that in leaning over to take a bow, a knife, pistol, and hand grenade fall out of his vest pockets). The wolf’s attorney insists that Red has guilt written all over her face, and a view of Red depicts just that – the word penned in cursive handwriting everywhere. (Years later, Robert McKimson would embellish this gag in Daffy Duck’s The Super Snooper, having “The Body” attempt to cover up these telltale signs by applying a bit of facial powder.) Wolf’s counsel implores the jurors that they all know Red’s side of the story – now it’s time to hear the wolf’s side – and turns over the presentation to the wolf himself. (Another cinematic piece of procedural nonsense. Rarely if ever is a witness, especially in a civil case, permitted, or allowed by his/her own counsel, to testify in his/her own words. Proper procedure is question and answer between counsel and client or defendant – allowing the attorney to hopefully keep the scope of inquiry within the bounds of relevancy, and most importantly, keeping the witness in line so that he does not inadvertently blurt something out detrimental to his case – the proverbial situation of a “loose cannon”.)

The Wolf begins, describing himself as coming home from “the pool hall – I mean, Sunday School.” The scene dissolves to a visual rendition of his testimony. The Wolf skips effeminately though fields of flowers, picking a boquet for his dear old mother. His outfit is a curious nod to the Disney shop, as from the waist up, he wears an outfit identical to Donald Duck’s sailor suit, while from the waist down, he wears a blue version of Mickey Mouse’s pants and Mickey-style shoes. What, they couldn’t find a place for Goofy’s suspenders? The Wolf “converses with nature”, saying hello to a bluebird, who shouts back in Mel’s “Spacely” shout, “Go on, ya jerk! Act your own age!” But, the Wolf claims, behind his back there was “sabota-gee”. Red appears, using her cape to full advantage to skulk like a melodrama villain. She pretends to weep, leaning against a tree, but sticks her foot out to trip the Wolf as he passes. The chivalrous wolf offers assistance. “Why doth thou weep, Toots? – Er, Fair Maid?” Red claims to have lost her way to Grandmother’s. The Wolf pulls out his own custom compass to get his bearings – with pointer markings not only indicating directions to Grandma’s, but the three pigs, three bears, and the house that Jack built. As the Wolf prepares to “lead the way”, Red does the leading for him, scooping the Wolf up in the sidecar of a motorcycle, and speeding both of them off to Grandma’s. Painted and neon signs on the house advertise the establishment as “Grandma Furrier – wolf furs a specialty.” Oblivious to these tell-tale warnings, the Wolf accompanies red to the door. Inside, an all-but-feeble Grandma practices dancing lessons to a conga record, until a warning signal flashes on the wall – “Jiggers, the Wolf”. Stashing away various coats on display under her her bed, Grandma jumps under the bedcovers and feigns moans of pain. Outside Red explains, “She has a terrific hangover – – that is, she’s very, very ill” and invites the Wolf in to cheer her up. The “invite” cosists of pushing the Wolf through the doorway, then bolting five doors and locks behind him to prevent an escape.

The Wolf begins, describing himself as coming home from “the pool hall – I mean, Sunday School.” The scene dissolves to a visual rendition of his testimony. The Wolf skips effeminately though fields of flowers, picking a boquet for his dear old mother. His outfit is a curious nod to the Disney shop, as from the waist up, he wears an outfit identical to Donald Duck’s sailor suit, while from the waist down, he wears a blue version of Mickey Mouse’s pants and Mickey-style shoes. What, they couldn’t find a place for Goofy’s suspenders? The Wolf “converses with nature”, saying hello to a bluebird, who shouts back in Mel’s “Spacely” shout, “Go on, ya jerk! Act your own age!” But, the Wolf claims, behind his back there was “sabota-gee”. Red appears, using her cape to full advantage to skulk like a melodrama villain. She pretends to weep, leaning against a tree, but sticks her foot out to trip the Wolf as he passes. The chivalrous wolf offers assistance. “Why doth thou weep, Toots? – Er, Fair Maid?” Red claims to have lost her way to Grandmother’s. The Wolf pulls out his own custom compass to get his bearings – with pointer markings not only indicating directions to Grandma’s, but the three pigs, three bears, and the house that Jack built. As the Wolf prepares to “lead the way”, Red does the leading for him, scooping the Wolf up in the sidecar of a motorcycle, and speeding both of them off to Grandma’s. Painted and neon signs on the house advertise the establishment as “Grandma Furrier – wolf furs a specialty.” Oblivious to these tell-tale warnings, the Wolf accompanies red to the door. Inside, an all-but-feeble Grandma practices dancing lessons to a conga record, until a warning signal flashes on the wall – “Jiggers, the Wolf”. Stashing away various coats on display under her her bed, Grandma jumps under the bedcovers and feigns moans of pain. Outside Red explains, “She has a terrific hangover – – that is, she’s very, very ill” and invites the Wolf in to cheer her up. The “invite” cosists of pushing the Wolf through the doorway, then bolting five doors and locks behind him to prevent an escape.

Grandma initiates the “My what a you have” routine, getting to a comment on the Wolf’s “beautiful fur coat”, with as aside to the audience that it should bring about $35.00. The Wolf replies that he tries to be tidy. Then grandma produces her first weapon. “My what a big mallet you have!” observes the wolf. Pretense is over, and the chase is on. Friz hasn’t been working in the same studio as Tex Avery for nothing, and copycats an Avery technique of having the characters run so fast, they do laps arount the walls. Then, he initiates a sequence of his own, with a series of surprise doors, upon the opening of which Granny is revealed, with increasingly bigger and more lethal weapons – a dagger, a machine gun, and a cannon. (The gag would be repeated with similar weaponry a few years later by Frank Tashlin as Daffy tries to escape from spy Hata Mari in Plane Daffy.) Finally, the Wolf reaches the real exit of the cottage (What happened to the five locked doors?), but takes only one step outward before receiving a resounding conk from Grandma’s original mallet outside. Grandma pounces on the Wolf, and grips him in a stranglehold, as the scene dissolves back to the courtroom, and the Wolf concludes without detail that only by a miracle did he escape with his life. To his surprise, a shot of the jury receals that his improbable story has entirely lost him his receptive audience, who mutter derogatory comments among themselves, and impatiently drum their fingers. In a last ditch attempt to sustain his credibility, the Wolf adds, “And if that ain’t the truth, I hope I get run over by a streetcar.” On cue, a real streetcar derails and plows through the wall of the courtroom, flattening the Wolf (a gag which Freleng would reuse as an ending about a decade later in His Hare-Raising Tale). Apologetically, the Wolf concludes, “Well, maybe I did exaggerate just a little bit”, as a stray brick falls on his head for the iris out.

Grandma initiates the “My what a you have” routine, getting to a comment on the Wolf’s “beautiful fur coat”, with as aside to the audience that it should bring about $35.00. The Wolf replies that he tries to be tidy. Then grandma produces her first weapon. “My what a big mallet you have!” observes the wolf. Pretense is over, and the chase is on. Friz hasn’t been working in the same studio as Tex Avery for nothing, and copycats an Avery technique of having the characters run so fast, they do laps arount the walls. Then, he initiates a sequence of his own, with a series of surprise doors, upon the opening of which Granny is revealed, with increasingly bigger and more lethal weapons – a dagger, a machine gun, and a cannon. (The gag would be repeated with similar weaponry a few years later by Frank Tashlin as Daffy tries to escape from spy Hata Mari in Plane Daffy.) Finally, the Wolf reaches the real exit of the cottage (What happened to the five locked doors?), but takes only one step outward before receiving a resounding conk from Grandma’s original mallet outside. Grandma pounces on the Wolf, and grips him in a stranglehold, as the scene dissolves back to the courtroom, and the Wolf concludes without detail that only by a miracle did he escape with his life. To his surprise, a shot of the jury receals that his improbable story has entirely lost him his receptive audience, who mutter derogatory comments among themselves, and impatiently drum their fingers. In a last ditch attempt to sustain his credibility, the Wolf adds, “And if that ain’t the truth, I hope I get run over by a streetcar.” On cue, a real streetcar derails and plows through the wall of the courtroom, flattening the Wolf (a gag which Freleng would reuse as an ending about a decade later in His Hare-Raising Tale). Apologetically, the Wolf concludes, “Well, maybe I did exaggerate just a little bit”, as a stray brick falls on his head for the iris out.

The Henpecked Duck (Warner, Looney Tunes, Porky and Daffy, 8/30/41 – Robert Clampett, dir.), the only Hollywood cartoon to ever enter the halls of a divorce court, has been extensively reviewed in my previous article, “Holy Matrimony! And a Stack of storks (Part 1)” on this website, to which the reader is directed for full detail. Not much thought-out courtroom strategy here. Mrs. Daffy is purely bombastic, repeatedly shouting “I want a divorce!” and attempting to keep Daffy from getting a word in. Daffy is unusually apologetic, with no effort to blow up or backtalk wife or judge – truly henpecked as the title implies. Daffy saves himself from Judge Porky’s alimony decree by finally figuring out how to reverse a magic trick gone wrong in which he caused Mrs. Duck’s egg to accidentally disappear. The classic comeback is from a member of the audience – an old chicken, who remarks in Zazu Pitts style, “Alakazam and you get an egg? Oh dear. And for 15 years, I’ve been doin’ it the hard way.”

The Henpecked Duck (Warner, Looney Tunes, Porky and Daffy, 8/30/41 – Robert Clampett, dir.), the only Hollywood cartoon to ever enter the halls of a divorce court, has been extensively reviewed in my previous article, “Holy Matrimony! And a Stack of storks (Part 1)” on this website, to which the reader is directed for full detail. Not much thought-out courtroom strategy here. Mrs. Daffy is purely bombastic, repeatedly shouting “I want a divorce!” and attempting to keep Daffy from getting a word in. Daffy is unusually apologetic, with no effort to blow up or backtalk wife or judge – truly henpecked as the title implies. Daffy saves himself from Judge Porky’s alimony decree by finally figuring out how to reverse a magic trick gone wrong in which he caused Mrs. Duck’s egg to accidentally disappear. The classic comeback is from a member of the audience – an old chicken, who remarks in Zazu Pitts style, “Alakazam and you get an egg? Oh dear. And for 15 years, I’ve been doin’ it the hard way.”

The Hams That Couldn’t Be Cured (Lantz/Universal, Swing Symphony, 3/4/42 – Walter Lantz, dir.), actually doesn’t directly involve the courtroom – but the aftermath of trial, as sentence is about to be carried out. In Lantz’s answer to “The Trial of Mr. Wolf”, Big Bad (formally named here as “Mr. Algenon Wolf”), now up on charges for cruelty and abuse to the three little pigs, has received the ultimate penalty – a death sentence by hanging. “Before we drop you out of the picture”, says the sheriff, he offers the Wolf the opportunity for a few last words. In the voice of Edward G. Robinson, the Wolf insists he’s been framed – sabotaged by “those three fugitives from a football factory.” “Do I look like a killer?” he asks. “You said it, brother”, reply the onlooking pigs. The Wolf, transforming his voice to that of a mild-mannered Milquetoast, tells what really happened, and who huffed and puffed whose house down. In his little rose covered cottage, the Wolf earns a meager living as a music teacher. He busies himself with such peaceful activities as dusting the goldfish in a bowl, and crocheting a new bathtub – when along comes an insistent knock at the door. As the Wolf attempts to open it, the door is abruptly knocked off its hinges, flattening the Wolf, as the three pigs strut in aggressive fashion through the doorway. I’m not sure who used this gag first, as it was a little early for Avery – but the Wolf reappears from under the door as if climbing out of a basement staircase that had not before existed. Asking what he can do for the pigs, the pigs respond in “little tough guy” voices, “We want youse ta loin us to play music.” “Shoot da tune to us, goon.”

This cel and BG from “The Hams That Couldn’t Be Cured” is coincidentally up for auction on eBay this week.

The Herring Murder Mystery (Screen Gems/Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 1/20/44 – Dun Roman, dir.). A mild-mannered little fellow works into the late hours of the night in a cannery, in charge of packaging marinated herring. We watch the process, as a live herring screams pitifully before being dunked forcibly by the man into a barrel of marinade, held down in the mixture until limp, then placed and sealed in a can. The man is not proud of his deeds, and addresses the audience, recognizing that he’s nothing but “a common murder – What a way to make a living.” Later that night, as he attempts to walk home along the docks in a foggy mist, he is sure he hears footsteps following him, and a little fancy footwork quickly confirms his suspicions that many of the footfalls heard are not his own. Running into a patch of fog, he collides with someone in the dark, then falls into a trash can. A voice asks him if he has a match, and when the man lights one, he finds himself face to face with a huge fish, human sized and walking on its tail fins, dressed in the manner of Sherlock Holmes. “Aren’t you afraid being out so late in the dark?”, asks the fish. Stammering, the man answers, “N-n–no. Why?” “The Marinator”, responds the fish, handing the man his business card, “Sherlock Shad – homicide division. “Don’t you read the papers? 500 cases of marinated herring this week, and all in this vicinity.” The little man trembles in the trash can from fear of being discovered, a nice touch being the shot of his hand holding the business card, quivering with fright until he can’t hold it steady. His fears are quickly realized, as several additional fish dressed as policemen surround the can, one of them clamping a lid over the man. The fish lift the can and, with the man inside, drop the can off the dock into the bay.

The Herring Murder Mystery (Screen Gems/Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 1/20/44 – Dun Roman, dir.). A mild-mannered little fellow works into the late hours of the night in a cannery, in charge of packaging marinated herring. We watch the process, as a live herring screams pitifully before being dunked forcibly by the man into a barrel of marinade, held down in the mixture until limp, then placed and sealed in a can. The man is not proud of his deeds, and addresses the audience, recognizing that he’s nothing but “a common murder – What a way to make a living.” Later that night, as he attempts to walk home along the docks in a foggy mist, he is sure he hears footsteps following him, and a little fancy footwork quickly confirms his suspicions that many of the footfalls heard are not his own. Running into a patch of fog, he collides with someone in the dark, then falls into a trash can. A voice asks him if he has a match, and when the man lights one, he finds himself face to face with a huge fish, human sized and walking on its tail fins, dressed in the manner of Sherlock Holmes. “Aren’t you afraid being out so late in the dark?”, asks the fish. Stammering, the man answers, “N-n–no. Why?” “The Marinator”, responds the fish, handing the man his business card, “Sherlock Shad – homicide division. “Don’t you read the papers? 500 cases of marinated herring this week, and all in this vicinity.” The little man trembles in the trash can from fear of being discovered, a nice touch being the shot of his hand holding the business card, quivering with fright until he can’t hold it steady. His fears are quickly realized, as several additional fish dressed as policemen surround the can, one of them clamping a lid over the man. The fish lift the can and, with the man inside, drop the can off the dock into the bay.

The can descends into the waters, its progress slowed by an octopus who seizes it in its tentacles and acts as a drag chute, then empties the man out before reaching the bottom, landing him in the testifying chair of an undersea courtroom. The audio ambience changes notably at this point, developing a studio-style reverb as if from a broadcast, as the entire mood of the episode transforms for a noir-detective spoof to a full blown parody of the then-popular radio quiz show, “Information, Please.” The show’s premise was a celebrity panel who are fielded various questions by a moderator from submissions mailed in by the listening audience (with a recurring gimmick of multi-part questions where the panel was expected to get at least “two out of three” or the like, and “musical: questions” using a song as a clue), and submitters who stumped the panel were frequently awarded copies of the Encyclopedia Brittanica. All these buttons are pushed in the course of the cartoon (including adding an impression of one of the show’s actual panelists, who found any excuse at the drop of a hat to toss in an anecdote about his personal love, baseball). The judge (a fish), and the prosecuting attorney (a shark), are both voiced by John McLeish (Goofy’s “How To” narrator). The trial is a comic travesty of utter nonsense, with the charges proclaimed by the panel of experts in the form of an “answer three out of four” question. The prosecutor himself announces the charge of “marinating with a barrel of vinegar”, and pointedly addresses the accused with “You know all about that, don’t you?” “Yes – – I mean no!” responds the little man. Hearing this incriminating response, the jurors break into a musical jingle – “There’s something on the end of the hook – but it’s shad roe, shad roe, shad roe to me.” To make matters clear, the judge looks up “shad roe’ in one of his own encyclopedias, finding it defined as “a lot of baloney”. (Note to radio buffs: I have actually encountered on at least one old broadcast a real sound-alike to the “Shad Roe” jingle, complete with a metallic clunk heard at the end which is also included in the cartoon, but cannot now for the life of me remember if it was actually used on “Information Please” or some other show, and what product it promoted. Can anyone provide this missing information?)

The can descends into the waters, its progress slowed by an octopus who seizes it in its tentacles and acts as a drag chute, then empties the man out before reaching the bottom, landing him in the testifying chair of an undersea courtroom. The audio ambience changes notably at this point, developing a studio-style reverb as if from a broadcast, as the entire mood of the episode transforms for a noir-detective spoof to a full blown parody of the then-popular radio quiz show, “Information, Please.” The show’s premise was a celebrity panel who are fielded various questions by a moderator from submissions mailed in by the listening audience (with a recurring gimmick of multi-part questions where the panel was expected to get at least “two out of three” or the like, and “musical: questions” using a song as a clue), and submitters who stumped the panel were frequently awarded copies of the Encyclopedia Brittanica. All these buttons are pushed in the course of the cartoon (including adding an impression of one of the show’s actual panelists, who found any excuse at the drop of a hat to toss in an anecdote about his personal love, baseball). The judge (a fish), and the prosecuting attorney (a shark), are both voiced by John McLeish (Goofy’s “How To” narrator). The trial is a comic travesty of utter nonsense, with the charges proclaimed by the panel of experts in the form of an “answer three out of four” question. The prosecutor himself announces the charge of “marinating with a barrel of vinegar”, and pointedly addresses the accused with “You know all about that, don’t you?” “Yes – – I mean no!” responds the little man. Hearing this incriminating response, the jurors break into a musical jingle – “There’s something on the end of the hook – but it’s shad roe, shad roe, shad roe to me.” To make matters clear, the judge looks up “shad roe’ in one of his own encyclopedias, finding it defined as “a lot of baloney”. (Note to radio buffs: I have actually encountered on at least one old broadcast a real sound-alike to the “Shad Roe” jingle, complete with a metallic clunk heard at the end which is also included in the cartoon, but cannot now for the life of me remember if it was actually used on “Information Please” or some other show, and what product it promoted. Can anyone provide this missing information?)

As the trial progresses, the jingle becomes a regular earache to all concerned, every time the man makes a suspect statement. The judge mildly remarks that it’s a “lovely thing”, but that if he hears it once more he’ll toss the jury out on their ears. A decidedly off-the-wall (or should I say “off the screen”?) moment comes as the little man attempts to answer a question, but no sound is heard from his lips. “Is anything wrong with the sound track?”. asks the judge, looking off to camera left. The screen image shifts to reveal the film sprocket holes, and a wiggly soundtrack line between picture and holes. The soundtrack line bends, angling into outline profile of a human face, which speaks up to the judge – “No, there’s nothing wrong with the sound track!”, then addresses the little man – “Just speak a little more distinctly, stupid!” Finally, the prosecutor offers to re-enact the crime, using the little man as the herring to force into the barrel. The jury breaks into the “Shad Roe” song again, and the little man offers a full confession – anything, provided the jury stop singing that song. But before the confession is entered on the record by the octopus court reporter, a shout is heard to let the man go. The voice comes from Exhibit “A” – one of the herring cans – from the herring inside of it, who’s not dead after all. Though not explained by the film with crystal clarity, it appears the inference of the herring’s testimony equates “marinated” with mere intoxication, and the herring likes it The judge acknowledges that he likes it too, and pronounces, “Case dismissed.” But the jury’s not finished, and starts to sing the “Shad Roe” song yet again. The judge has had enough, and flips over the surface of the judge’s bench, under which rests a sardine can, into which the judge leaps, rolling closed the can lid behind him, upon which are printed the words, “The End.”

As the trial progresses, the jingle becomes a regular earache to all concerned, every time the man makes a suspect statement. The judge mildly remarks that it’s a “lovely thing”, but that if he hears it once more he’ll toss the jury out on their ears. A decidedly off-the-wall (or should I say “off the screen”?) moment comes as the little man attempts to answer a question, but no sound is heard from his lips. “Is anything wrong with the sound track?”. asks the judge, looking off to camera left. The screen image shifts to reveal the film sprocket holes, and a wiggly soundtrack line between picture and holes. The soundtrack line bends, angling into outline profile of a human face, which speaks up to the judge – “No, there’s nothing wrong with the sound track!”, then addresses the little man – “Just speak a little more distinctly, stupid!” Finally, the prosecutor offers to re-enact the crime, using the little man as the herring to force into the barrel. The jury breaks into the “Shad Roe” song again, and the little man offers a full confession – anything, provided the jury stop singing that song. But before the confession is entered on the record by the octopus court reporter, a shout is heard to let the man go. The voice comes from Exhibit “A” – one of the herring cans – from the herring inside of it, who’s not dead after all. Though not explained by the film with crystal clarity, it appears the inference of the herring’s testimony equates “marinated” with mere intoxication, and the herring likes it The judge acknowledges that he likes it too, and pronounces, “Case dismissed.” But the jury’s not finished, and starts to sing the “Shad Roe” song yet again. The judge has had enough, and flips over the surface of the judge’s bench, under which rests a sardine can, into which the judge leaps, rolling closed the can lid behind him, upon which are printed the words, “The End.”

Book Revue (Warner, Daffy Duck, 1/5/46 – Robert Clampett, dir.), has been encountered briefly on previous trails. Clampett modernizes the traditional 1930’s “midnight in a store” settings, taking Tashlin’s “Speaking of the Weather” setup from magazine rack to book store. The film again features a brief courtroom scene, embellishing on Tashlin’s. The Big Bad Wolf is picked up and arrested by a mile long blue-coated arm from the book, “Long Arm of the Law”. He is again placed before a copy of “Judge” magazine, where the presiding judge issues his verdict in song, set to the tune of the Sextet from the opera, “Lucia Di Lammermoor”: “You are guilty, and the sentence is…” (You guessed it) “…LIFE!” In typical Rod Scribner animated overacting, the Wolf pleads “No!”, and the Judge insists “Yes!” As the Wolf is thrown into a jail cell depicted on the cover of the magazine, he concludes the aria with the couplet, “You can’t do this to me! I’m a citizen, see!” He of course immediately escapes, but is tripped up by Jimmy Durante’s nose from the book “So Big”, slides down “Skid Row”, and straight into “Dante’s Inferno” (after a quick dose of swoon induced by the crooning of Frank Sinatra).

Book Revue (Warner, Daffy Duck, 1/5/46 – Robert Clampett, dir.), has been encountered briefly on previous trails. Clampett modernizes the traditional 1930’s “midnight in a store” settings, taking Tashlin’s “Speaking of the Weather” setup from magazine rack to book store. The film again features a brief courtroom scene, embellishing on Tashlin’s. The Big Bad Wolf is picked up and arrested by a mile long blue-coated arm from the book, “Long Arm of the Law”. He is again placed before a copy of “Judge” magazine, where the presiding judge issues his verdict in song, set to the tune of the Sextet from the opera, “Lucia Di Lammermoor”: “You are guilty, and the sentence is…” (You guessed it) “…LIFE!” In typical Rod Scribner animated overacting, the Wolf pleads “No!”, and the Judge insists “Yes!” As the Wolf is thrown into a jail cell depicted on the cover of the magazine, he concludes the aria with the couplet, “You can’t do this to me! I’m a citizen, see!” He of course immediately escapes, but is tripped up by Jimmy Durante’s nose from the book “So Big”, slides down “Skid Row”, and straight into “Dante’s Inferno” (after a quick dose of swoon induced by the crooning of Frank Sinatra).

Daffy Doodles (Warner, Porky and Daffy, 4/5/46 – Robert McKimson, directorial debut), presents an unusual story premise which does not appear to have been exploited by any other cartoon – the manhunt for a “moustache fiend” – who doodles moustaches on all the billboards and advertisements! The fiend turns out to be Daffy Duck, who leads Officer Porky Pig on a merry chase through six minutes of the cartoon (while at the same time finding numerous excuses to apply generous helpings of black paint to Porky’s upper lip). Finally captured, Daffy pleads his case before a level-headed judge. “Don’t send me to Sing Sing…Sing…Sing… Be magnanimous! You might be a fiend yourself someday!” (Not a recommended line to say to any to any judicial officer!) The judge turns the decision over to a jury – consisting of an entire panel of look-alike Jerry Colonnas, each with the comedian’s trademark gigantic handlebar moustache. “Ah yes…NOT GUILTY!”, they find in unison. Happy at regaining his liberty, Daffy swears to the judge, “Never again will I paint another moustache……I’m doin’ BEARDS now!” For the final shot, he whips out his paintbrush, draws a beard on the judge, then plasters paint in broad strokes over the camera lens to black out the view for the final fade in of the Warner rings. (Or was it still a Porky Pig drum in the original release?)

Daffy Doodles (Warner, Porky and Daffy, 4/5/46 – Robert McKimson, directorial debut), presents an unusual story premise which does not appear to have been exploited by any other cartoon – the manhunt for a “moustache fiend” – who doodles moustaches on all the billboards and advertisements! The fiend turns out to be Daffy Duck, who leads Officer Porky Pig on a merry chase through six minutes of the cartoon (while at the same time finding numerous excuses to apply generous helpings of black paint to Porky’s upper lip). Finally captured, Daffy pleads his case before a level-headed judge. “Don’t send me to Sing Sing…Sing…Sing… Be magnanimous! You might be a fiend yourself someday!” (Not a recommended line to say to any to any judicial officer!) The judge turns the decision over to a jury – consisting of an entire panel of look-alike Jerry Colonnas, each with the comedian’s trademark gigantic handlebar moustache. “Ah yes…NOT GUILTY!”, they find in unison. Happy at regaining his liberty, Daffy swears to the judge, “Never again will I paint another moustache……I’m doin’ BEARDS now!” For the final shot, he whips out his paintbrush, draws a beard on the judge, then plasters paint in broad strokes over the camera lens to black out the view for the final fade in of the Warner rings. (Or was it still a Porky Pig drum in the original release?)

A short recess, and more testimony next week.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

That violin exercise familiar to fans of the Jack Benny program is the second in the book of 42 etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, or Kreutzer #2 for short. Kreutzer was a French violinist and composer (his German-born father was a musician in the court orchestra of Louis XIV) who was appointed the first professor of violin at the Paris Conservatoire when it was founded in 1795. As such he was one of the most influential violin teachers in history, and his book of etudes is an important part of the training of every violinist and violist in the world. The first etude in the set, an exercise in bow control at a very slow tempo, is actually quite difficult; hence students invariably begin with #2.

I still have my Kreutzer book from my student days (and in fact I worked my way through it again last year to keep in shape after the pandemic cancelled my entire concert schedule). #2 is only half a page long, but it is provided with a full page of thirty bowing and rhythmic variations, as well as others that my viola teacher penciled in the margins. Since my teacher always wrote down the date of the assignment on the music, I can see that I spent no less than five weeks working on Kreutzer #2. Every week he would time me with a stopwatch to see how fast I could play it without making a mistake, and over those five weeks I brought my time down from 57″ to 43″.

The Kreutzer etudes are not for beginners, but for intermediate to advanced students. I was a senior in high school when I worked on them. The joke always was that Jack Benny practised #2 week after week, year after year, without making any progress. But if you have a teacher who can show you how to approach it creatively, it’s a very useful study.

Darryl Calker’s jazzy variation on Kreutzer #2 is quite clever. The etude turns up in other cartoons, usually in a pedagogical setting: for example, Baby Bear practises it at the beginning of “The Three Bears” (Terrytoons, 1939). I know I’ve heard it in another Terrytoon, accompanying a chase scene, but I can’t offhand remember which one. And of course, there’s “The Mouse That Jack Built”, starring Jack Benny himself. “Who’s this guy Isaac Stern?” He’s a guy who diligently practised his Kreutzer etudes, I can tell you that!

I just wanna extend my personal thanx to Charles Gardner for yet another excellent and informative posting. Your research and presentations are greatly appreciated. I look forward to more of the same in the future.

A little late for your timeline (wish I’d remembered it last week), but Oswald the Lucky Rabbit was put on trial for the murder of Cock Robin in somewhat misleadingly titled “The Detective” (9/22/1930). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVZO0yRIWzY

What cartoon was Phony Baloney in before “Frozen Feet”? I only know of his two later Technicolor cartoons from the fifties, in which he’s depicted as being of much smaller stature, almost leprechaun-like.

Those Arctic penguins always bothered me too, to say nothing of all the African tigers and South Sea Island gorillas one finds in old cartoons. Say what you will of the great animators of yore, biogeography wasn’t their strong suit. When “Life Begins for Andy Panda”, presumably in a Chinese bamboo forest, his birth is attended by such North American species as skunks, raccoons, beaver, moose and mockingbirds, not to mention a kangaroo and a tribe of topknotted pygmies. And in “Devil May Hare”, we see a deer, moose, bighorn sheep, monkey, ostrich, polar bear and lion all stampede through the Tasmanian bush! But they’re still visually arresting and very entertaining cartoons.

That said, I’d love it if all those North Polar Penguins had been replaced with… puffins! And as far as Arctic animals go, what about narwhals? Think of the corkscrew gags!

The “Information Please” spoof is well-observed, and a number of the individuals are recognizable. The sportswriter John Kieran (the baseball expert) is the jug-eared sea creature seen briefly, and Oscar Levant (as the darker fish) is seen twice (though he was NOT the baseball expert). The joshing of Clifton Fadiman is especially well done, in my view. Odd that F.P. Adams wasn’t shown, since he was quite recognizable.