Merry Christmas! But then, probably every other column this week is saying that. Our attention is still in a looking-forward mode to the new decade just around the corner. As the announcer in many a Goofy sports cartoon has observed, “The seconds are rapidly disappearing.” So, we continue our survey of clocks as central figures in animation history, and of Father Time’s periodic visits to keep things in sync. We further highlight a series of timely tales by Friz Freleng using a recurring pattern of dramatic buildup. And I also include a special bonus “Christmas present” – some neat time-related children’s audio recordings by a batch of animation veterans, which should properly have become cartoons in their own right.

Friz Freleng found recurring instances where he could use a clock to major advantage to heighten suspense and urgency in a cartoon by a progressive “countdown” until some anticipated adverse event was supposed to happen to a principal character. This vehicle of storytelling was perhaps adapted from a couple of nearly-twin earlier storylines from other studios which utilized an impending time deadline but didn’t play it up to quite such a degree. The better of the two prior examples was Mickey’s Service Station (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 3/16/35 – Ben Sharpsteen, dir.), where gangster Peg Leg Pete gives Mickey, Donald and Goofy just ten minutes to remove a squeak from his car – or makes a gesture that he’ll slit their throats. A cut back to a clock chiming the appointed hour at the end of the cartoon has its face morph into Pete’s, repeating the throat-slitting gesture. Popeye’s Service With a Guile (Paramount/Famous, 4/19/46 – Bill Tytla, dir.) repeats almost the same situation as the Mickey, with the owner of the car being the admiral wanting a tire changed by a time deadline (which is actually not emphasized visually by cutaways to clocks but only verbally referenced).

Freleng’s first notable use of the story device occurred in Slick Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 11/1/47). At the Mocrumbo restaurant in Hollywood (Dinner $600.00. Small Down Payment. No Co-signors Necessary), waiter Elmer Fudd receives an order for fried rabbit from patron Humphrey Bogart. Despite Elmer informing Mr. Bogart that they’re “fwesh outta wabbit”, Bogie demands rabbit within 20 minutes, or else (producing a Tommy gun on the table). A distraught Elmer finds hope in the kitchen, in the form of a stowaway inside a just-delivered crate of carrots – Bugs Bunny, of course. The chase which follows is well punctuated by celebrity cameos and additional bad celebrity impersonations by Bugs – topped with an elaborate latin dance as Bugs provides an impromptu follow-up act after Carmen Miranda. But all the while the clock keeps ticking. As Bogie gives Elmer a final five minute warning, the kitchen clock rapidly whirls around – but Bugs is nowhere to be found. The clock hits the appointed time, and chimes with a deafening array of bells, whistles, and sirens, and a light-up display below reading “Time’s up”. Elmer pleads to Bogart how he “twied and twied”, and cringes as Bogart reaches into his lapel pocket. But instead of producing his “heater”, Bogart merely pulls out a handkerchief and mops his brow, saying “Baby will just have to have a ham sandwich instead.” “Baby?” shouts Bugs, appearing from inside a pot. Outside at the table sits Mrs. Bogart – Lauren Bacall. Bugs zooms to the table, placing himself squarely on a dinner plate before her, and hollering to Elmer, “Remember, Garcon, the customer is always right. If it’s rabbit Baby wants, rabbit Baby gets!” The scene irises out while Bugs impresses Mrs. Bogart with a series of howls and whistles rivaling Tex Avery’s wolf’s usual reactions to Red Hot Riding Hood.

Freleng’s first notable use of the story device occurred in Slick Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 11/1/47). At the Mocrumbo restaurant in Hollywood (Dinner $600.00. Small Down Payment. No Co-signors Necessary), waiter Elmer Fudd receives an order for fried rabbit from patron Humphrey Bogart. Despite Elmer informing Mr. Bogart that they’re “fwesh outta wabbit”, Bogie demands rabbit within 20 minutes, or else (producing a Tommy gun on the table). A distraught Elmer finds hope in the kitchen, in the form of a stowaway inside a just-delivered crate of carrots – Bugs Bunny, of course. The chase which follows is well punctuated by celebrity cameos and additional bad celebrity impersonations by Bugs – topped with an elaborate latin dance as Bugs provides an impromptu follow-up act after Carmen Miranda. But all the while the clock keeps ticking. As Bogie gives Elmer a final five minute warning, the kitchen clock rapidly whirls around – but Bugs is nowhere to be found. The clock hits the appointed time, and chimes with a deafening array of bells, whistles, and sirens, and a light-up display below reading “Time’s up”. Elmer pleads to Bogart how he “twied and twied”, and cringes as Bogart reaches into his lapel pocket. But instead of producing his “heater”, Bogart merely pulls out a handkerchief and mops his brow, saying “Baby will just have to have a ham sandwich instead.” “Baby?” shouts Bugs, appearing from inside a pot. Outside at the table sits Mrs. Bogart – Lauren Bacall. Bugs zooms to the table, placing himself squarely on a dinner plate before her, and hollering to Elmer, “Remember, Garcon, the customer is always right. If it’s rabbit Baby wants, rabbit Baby gets!” The scene irises out while Bugs impresses Mrs. Bogart with a series of howls and whistles rivaling Tex Avery’s wolf’s usual reactions to Red Hot Riding Hood.

Golden Yeggs (Warner, Daffy Duck, 8/5/50) marks the first appearance of Freleng favorite, the little mobster kingpin known as “Rocky”. At Porky Pig’s barnyard, the poultry can’t stop clucking about the discovery of a golden egg in one of the nests. “W-w-who did this?”, asks Porky. The real goose who laid it isn’s about to take the credit, remembering the ill fate that befell the goose that laid the golden egg in the storybooks – and instead points the finger of implication to Daffy Duck. Daffy (obviously less than familiar with the old story) can’t resist the lure of fame – and plays along with the gag. The press is called in, and newspaper and magazine headlines herald Porky’s good fortune. Rocky, reading such story in a sleazy apartment, tells his strongarm henchmen, “That’s better than the numbers racket”, and announces, “We’re goin’ into the poultry business.” Porky is “persuaded” to sell the duck – by means of a shovel broken over his head. Taken to the crooks’ apartment, Daffy is told to get busy and make with the eggs. Knowing he’s a fraud, Daffy stalls for time, insisting he needs inspiration as an artist, insisting on beautiful surroundings. The gangsters oblige for a while, installing Daffy in a floating nest in a swimming pool. But when Daffy further stalls, one of the hoods uses a special torpedo-launching pistol to blast Daffy out of the water.

Golden Yeggs (Warner, Daffy Duck, 8/5/50) marks the first appearance of Freleng favorite, the little mobster kingpin known as “Rocky”. At Porky Pig’s barnyard, the poultry can’t stop clucking about the discovery of a golden egg in one of the nests. “W-w-who did this?”, asks Porky. The real goose who laid it isn’s about to take the credit, remembering the ill fate that befell the goose that laid the golden egg in the storybooks – and instead points the finger of implication to Daffy Duck. Daffy (obviously less than familiar with the old story) can’t resist the lure of fame – and plays along with the gag. The press is called in, and newspaper and magazine headlines herald Porky’s good fortune. Rocky, reading such story in a sleazy apartment, tells his strongarm henchmen, “That’s better than the numbers racket”, and announces, “We’re goin’ into the poultry business.” Porky is “persuaded” to sell the duck – by means of a shovel broken over his head. Taken to the crooks’ apartment, Daffy is told to get busy and make with the eggs. Knowing he’s a fraud, Daffy stalls for time, insisting he needs inspiration as an artist, insisting on beautiful surroundings. The gangsters oblige for a while, installing Daffy in a floating nest in a swimming pool. But when Daffy further stalls, one of the hoods uses a special torpedo-launching pistol to blast Daffy out of the water.

Back in the hoods’ apartment, Daffy is given just five minutes to lay an egg, or Blam, Blam, Blam. Daffy insists on privacy – which he uses to attempt to sneak out. But the gangsters beat him to every source of an exit – posing in place of escape doors by merely holding a doorknob in their hand; having Daffy delivered back to them from a dive in the laundry chute as folded laundry; and waiting at the end of a string of tied bedsheets Daffy drops out the window. At each failure, Rocky announces a “countdown” – “Four minutes”….”Three minutes”…..and even holding up a sign reading “One minute”. In the same manner as “Slick Hare”, a clock on the wall rapidly counts down the seconds with a sweep second hand, then goes off with whistles and sirens when time runs out (Daffy this time trying to “shush” the clock, then taking a mallet to it to bust it open). But the crooks have heard, and on finding no egg, Rocky points his gun at Daffy, stating, “So long, pal.” He fires, taking the scalp off of Daffy’s brow. But simultaneous with the shot, a “boink” is heard on the soundtrack. Daffy turns around – and a golden egg rests on the floor! Daffy nervously remarks, “You don’t know what you can do until you’ve got a gun against your head.” Assuming he has satisfied his end of the bargain, Daffy attempts to leave. But Rocky blocks his path with pistol still at the ready, and points to a closet. Inside rests a tall pyramid of empty egg crates. “Fill ‘em up”, orders Rocky. “Oh, my aching back!”, moans Daffy, and faints on the spot.

Back in the hoods’ apartment, Daffy is given just five minutes to lay an egg, or Blam, Blam, Blam. Daffy insists on privacy – which he uses to attempt to sneak out. But the gangsters beat him to every source of an exit – posing in place of escape doors by merely holding a doorknob in their hand; having Daffy delivered back to them from a dive in the laundry chute as folded laundry; and waiting at the end of a string of tied bedsheets Daffy drops out the window. At each failure, Rocky announces a “countdown” – “Four minutes”….”Three minutes”…..and even holding up a sign reading “One minute”. In the same manner as “Slick Hare”, a clock on the wall rapidly counts down the seconds with a sweep second hand, then goes off with whistles and sirens when time runs out (Daffy this time trying to “shush” the clock, then taking a mallet to it to bust it open). But the crooks have heard, and on finding no egg, Rocky points his gun at Daffy, stating, “So long, pal.” He fires, taking the scalp off of Daffy’s brow. But simultaneous with the shot, a “boink” is heard on the soundtrack. Daffy turns around – and a golden egg rests on the floor! Daffy nervously remarks, “You don’t know what you can do until you’ve got a gun against your head.” Assuming he has satisfied his end of the bargain, Daffy attempts to leave. But Rocky blocks his path with pistol still at the ready, and points to a closet. Inside rests a tall pyramid of empty egg crates. “Fill ‘em up”, orders Rocky. “Oh, my aching back!”, moans Daffy, and faints on the spot.

Years later, without the visual use of a clock to build the suspense, Freleng’s later studio (or more precisely, his writing staff and a group of Barcelona animators to whom the project was handed on a “loan-out” basis), would revisit the “countdown” storytelling vehicle in close resemblance to Golden Yeggs in Hoot Kloot’s The Badge and the Beautiful (DePatie-Freleng/UA, 4/17/74 – Bob Balsar, dir.). Ornery female behemoth Calamatous Jane rides into town in a whip-snapping mood and terrorizes the local saloon. Sheriff Hoot rushes in to impose disturbing the peace charges, with his usual threat that she’s in “a heap o’ trouble”. One look at Hoot, and Calamatous is smitten, and unilaterally decides that Hoot is matrimonial material. Hoot telles the audience, “She ain’t in a heap o’ trouble. I am!” After several whip cracks at him, Hoot’s clothes are torn away, reducing him to long underwear. Capturing him, Calamatous buys him a suitable wedding “trousseau” and installs him in the bridal suite of the local hotel, giving him the trademark Freleng “five minutes” to get dressed. Hoot’s first escape attempt is a direct lift of the bedsheets-out-the-window sequence from Golden Yeggs. Four minutes finds him attempting to jump out the window onto his horse Fester – only to have Fester take a whip snap in the rear from Calamatous to place him out of position while Hoot smashes into the ground. Three minutes has Kloot retrieve the key to the hotel room from Calamatous’s blouse-front below by way of a magnet, but get caught in the elevator while making his escape. Two minutes has Kloot race down the stairs into the cellar, then attempt to tunnel to freedom, only to find Calamatous already waiting for him in the newly-excavated tunnel. One minute has Kloot borrow an escape route from Warner’s Porky Pig’s Feat (1943), swinging a rope to catch a flagpole on the next building, then tying off the rope to attempt a tightrope walk. (If he had the rope, why did he use the bedsheets on the first escape attempt?) But the other end of the rope descends, sliding Hoot downward – right into the door or the Justice of the Peace. As the “I do”s are exchanged, all that saves Kloot from a fate worse than death is the timely arrival of Calamatous’s real fiancé, Butch Casualty, to stop the wedding.

Years later, without the visual use of a clock to build the suspense, Freleng’s later studio (or more precisely, his writing staff and a group of Barcelona animators to whom the project was handed on a “loan-out” basis), would revisit the “countdown” storytelling vehicle in close resemblance to Golden Yeggs in Hoot Kloot’s The Badge and the Beautiful (DePatie-Freleng/UA, 4/17/74 – Bob Balsar, dir.). Ornery female behemoth Calamatous Jane rides into town in a whip-snapping mood and terrorizes the local saloon. Sheriff Hoot rushes in to impose disturbing the peace charges, with his usual threat that she’s in “a heap o’ trouble”. One look at Hoot, and Calamatous is smitten, and unilaterally decides that Hoot is matrimonial material. Hoot telles the audience, “She ain’t in a heap o’ trouble. I am!” After several whip cracks at him, Hoot’s clothes are torn away, reducing him to long underwear. Capturing him, Calamatous buys him a suitable wedding “trousseau” and installs him in the bridal suite of the local hotel, giving him the trademark Freleng “five minutes” to get dressed. Hoot’s first escape attempt is a direct lift of the bedsheets-out-the-window sequence from Golden Yeggs. Four minutes finds him attempting to jump out the window onto his horse Fester – only to have Fester take a whip snap in the rear from Calamatous to place him out of position while Hoot smashes into the ground. Three minutes has Kloot retrieve the key to the hotel room from Calamatous’s blouse-front below by way of a magnet, but get caught in the elevator while making his escape. Two minutes has Kloot race down the stairs into the cellar, then attempt to tunnel to freedom, only to find Calamatous already waiting for him in the newly-excavated tunnel. One minute has Kloot borrow an escape route from Warner’s Porky Pig’s Feat (1943), swinging a rope to catch a flagpole on the next building, then tying off the rope to attempt a tightrope walk. (If he had the rope, why did he use the bedsheets on the first escape attempt?) But the other end of the rope descends, sliding Hoot downward – right into the door or the Justice of the Peace. As the “I do”s are exchanged, all that saves Kloot from a fate worse than death is the timely arrival of Calamatous’s real fiancé, Butch Casualty, to stop the wedding.

Although also not using clocks, and not even technically counting time, honorable mention should also be made of Freleng’s Satan’s Waitin’ (Warner, Tweety and Sylvester; 8/7/54), previously reviewed in my prior article Go To Hades (pt. 2), in which a countdown (of Sylvester’s remaining nine lives) is used as the plot vehicle throughout the cartoon. There was even a “countup”of sorts with Yosemite Sam, giving Bugs fewer and fewer seconds to stop his train – and fewer and fewer seconds for Yosemite to meet disaster – in Wild and Wooly Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/1/59).

At least two more Freleng episodes use a clock as a gag point. In Ain’t She Tweet? (Warner, Tweety and Sylvester, 6/21/52), Sylvester’s attempt to sneak across Granny’s front yard (chock full of vicious sleeping bulldogs) is disrupted by Tweety triggering an alarm clock near his cage. As the off-screen mauling gets underway, Tweety delivers the curtain line, “Now who do you suppose would want to disturb dose doggies so early in the morning?” The same gag is revisited, out of historical context, in Roman Legion-Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 11/12/55), as Bugs lowers an alarm clock on a string into a pit full of sleeping lions while Yosemite Sam is crossing it.

A Bear For Punishment (Warner, Looney Tunes (Three Bears), 10/20/51, Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.), the ultimate in disastrous celebrations of Father’s Day, includes a memorable opening. Junior Bear (a behemoth lummox lovingly voiced by Stan Freberg) can’t wait for the big day for Papa, and makes sure he’s not going to miss it – by setting up a table next to his bed with about forty alarm clocks, all set to go off at 4:30 a.m. The tintinnabulation of their simultaneous din jars Papa out of a sound sleep with his eyes transformed into alarm clock faces. Papa flies over to the table of clocks, and furiously tries to shut them down, but nothing seems to phase them. “How do you turn these blasted things off?”. he snarls to Junior. Junior calmly lifts one finger to his lips, and says, “Shhhh.” The clocks instantly fall silent, except for one small one that sneaks in a quiet little ring before stopping. Father turns to give the camera a blank stare that both registers total puzzlement and at the same time communicates, “Only my kid could do something this stupid” – then smashes one of the clocks into Junior’s face, its back flying open to create a sort of face out of the loose springs and gears.

A Bear For Punishment (Warner, Looney Tunes (Three Bears), 10/20/51, Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.), the ultimate in disastrous celebrations of Father’s Day, includes a memorable opening. Junior Bear (a behemoth lummox lovingly voiced by Stan Freberg) can’t wait for the big day for Papa, and makes sure he’s not going to miss it – by setting up a table next to his bed with about forty alarm clocks, all set to go off at 4:30 a.m. The tintinnabulation of their simultaneous din jars Papa out of a sound sleep with his eyes transformed into alarm clock faces. Papa flies over to the table of clocks, and furiously tries to shut them down, but nothing seems to phase them. “How do you turn these blasted things off?”. he snarls to Junior. Junior calmly lifts one finger to his lips, and says, “Shhhh.” The clocks instantly fall silent, except for one small one that sneaks in a quiet little ring before stopping. Father turns to give the camera a blank stare that both registers total puzzlement and at the same time communicates, “Only my kid could do something this stupid” – then smashes one of the clocks into Junior’s face, its back flying open to create a sort of face out of the loose springs and gears.

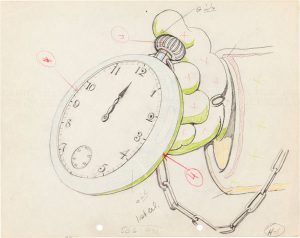

Alice in Wonderland (Disney/RKO, 7/26/51) gives its writers, and Mad Hatter Ed Wynn and March Hare Jerry Colonna, a chance to shine, in some original interpolation into Alice’s adventures at the mad tea party. A frustrated Alice, who just can’t get her message across to the demented duo amidst their nonsensical escapades at the tea table, prepares to leave in a huff, stating “I just haven’t the time” for such nonsense. Aghast, Colonna shouts to anyone who might hear, “The time! The time! Who’s got the time?” The only one with same is the passing White Rabbit, carrying his trademark pocket watch, and still complaining at how late he is. As he passes, the Hatter grabs hold of his watch and drags the rabbit to the table. “Well no wonder you’re late! Why this clock is exactly two days slow!” (A hilarious line in 1951, when calendar watches were uncommon, as being “exactly” two days slow would in fact mean the watch was telling completely accurate time.) The Hatter opens the watch, inspecting its interior by using a salt shaker instead of a jeweler’s glass, and concludes that the problem is that it’s “full of wheels”. Ad-libbing in typical Ed Wynn style, the Hatter applies his own methods of repair, with the March Hare passing ingredients – a slather of butter, half a pot of tea, a heaping glob of jam, two spoons of sugar (including jamming in the spoons themselves) – but draws the line when the March Hare suggests mustard. “Don’t let’s be silly! Lemon, now that’s different…” Slamming the watch closed, and cutting away all the ingredient spillage, the Hatter announces, “That should do it.” It does, all right, as the watch’s alarm goes off, it flies into the air, and bounces around the table out of control. Colonna lapses into his screaming mode while the eyes of the March Hare seem to pivot independently of each other, shouting “MAD WATCH! MAD WATCH!!” Pulling a huge mallet from nowhere, the Hare declares, “There’s only one way to stop a mad watch,” and clobbers the watch flat against the table (in a terrific touch, all color is simultaneously smashed out of the shot by the force of the blow). Entirely calm, the Hatter slides the flattened mess back to the White Rabbit, summing up the situation: “Two days slow, that’s what it is,”

Alice in Wonderland (Disney/RKO, 7/26/51) gives its writers, and Mad Hatter Ed Wynn and March Hare Jerry Colonna, a chance to shine, in some original interpolation into Alice’s adventures at the mad tea party. A frustrated Alice, who just can’t get her message across to the demented duo amidst their nonsensical escapades at the tea table, prepares to leave in a huff, stating “I just haven’t the time” for such nonsense. Aghast, Colonna shouts to anyone who might hear, “The time! The time! Who’s got the time?” The only one with same is the passing White Rabbit, carrying his trademark pocket watch, and still complaining at how late he is. As he passes, the Hatter grabs hold of his watch and drags the rabbit to the table. “Well no wonder you’re late! Why this clock is exactly two days slow!” (A hilarious line in 1951, when calendar watches were uncommon, as being “exactly” two days slow would in fact mean the watch was telling completely accurate time.) The Hatter opens the watch, inspecting its interior by using a salt shaker instead of a jeweler’s glass, and concludes that the problem is that it’s “full of wheels”. Ad-libbing in typical Ed Wynn style, the Hatter applies his own methods of repair, with the March Hare passing ingredients – a slather of butter, half a pot of tea, a heaping glob of jam, two spoons of sugar (including jamming in the spoons themselves) – but draws the line when the March Hare suggests mustard. “Don’t let’s be silly! Lemon, now that’s different…” Slamming the watch closed, and cutting away all the ingredient spillage, the Hatter announces, “That should do it.” It does, all right, as the watch’s alarm goes off, it flies into the air, and bounces around the table out of control. Colonna lapses into his screaming mode while the eyes of the March Hare seem to pivot independently of each other, shouting “MAD WATCH! MAD WATCH!!” Pulling a huge mallet from nowhere, the Hare declares, “There’s only one way to stop a mad watch,” and clobbers the watch flat against the table (in a terrific touch, all color is simultaneously smashed out of the shot by the force of the blow). Entirely calm, the Hatter slides the flattened mess back to the White Rabbit, summing up the situation: “Two days slow, that’s what it is,”

Land of Lost Watches (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon, 5/4/51 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.), the third and last in a series of cartoons based on the “Land of the Lost” children’s radio series about an undersea kingdom where every object on Earth that gets lost winds up, is unfortunately perhaps the least creative and most melodramatic of the three. As with all episodes, stock footage is used at the beginning and end to bring two kids from a fishing boat to the undersea land, through a guide fish named Red Lantern who gives each child magic seaweed to put in their pockets so that they can breathe underwater. (I’ve never heard one of the radio shows, but if the cartoons mirror them, yes, this was the cheesy caliber of children’s mass media entertainment in those days.) The boy (Billy – was every boy in Paramount cartoons named Billy?) asks if their Daddy’s pocket watch has turned up. At the palace of King Find-All (a walrus), he indeed is among the newly found lost objects awaiting “distribution”. As with all objects in the series, he has taken on a human-like personality, and developed hands, feet, and a “face” instead of just numbers and clock hands. However, he has met a shapely “golden gal” in the form of Rosita Wrist Watch, who is also about to be sorted. When called by King Find-All, she somersaults her way to the throne, and a turtle clerk reveals that she belonged to a lady acrobat. The king decides that she should go into show business – the “Big Time”. The pocket watch requests to go there too to stay with her – but the turtle notes that the Daddy that owned him was a doctor. King Find-All thus chooses to assign him to the Watch-pital. Billy intervenes, telling him that the watch’s timing was always perfect, and that he should be given a chance in Big Time. Find-All agrees to give him a tryout.

Land of Lost Watches (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon, 5/4/51 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.), the third and last in a series of cartoons based on the “Land of the Lost” children’s radio series about an undersea kingdom where every object on Earth that gets lost winds up, is unfortunately perhaps the least creative and most melodramatic of the three. As with all episodes, stock footage is used at the beginning and end to bring two kids from a fishing boat to the undersea land, through a guide fish named Red Lantern who gives each child magic seaweed to put in their pockets so that they can breathe underwater. (I’ve never heard one of the radio shows, but if the cartoons mirror them, yes, this was the cheesy caliber of children’s mass media entertainment in those days.) The boy (Billy – was every boy in Paramount cartoons named Billy?) asks if their Daddy’s pocket watch has turned up. At the palace of King Find-All (a walrus), he indeed is among the newly found lost objects awaiting “distribution”. As with all objects in the series, he has taken on a human-like personality, and developed hands, feet, and a “face” instead of just numbers and clock hands. However, he has met a shapely “golden gal” in the form of Rosita Wrist Watch, who is also about to be sorted. When called by King Find-All, she somersaults her way to the throne, and a turtle clerk reveals that she belonged to a lady acrobat. The king decides that she should go into show business – the “Big Time”. The pocket watch requests to go there too to stay with her – but the turtle notes that the Daddy that owned him was a doctor. King Find-All thus chooses to assign him to the Watch-pital. Billy intervenes, telling him that the watch’s timing was always perfect, and that he should be given a chance in Big Time. Find-All agrees to give him a tryout.

That evening, at an all-clock vaudeville theater, the pocket watch tries to perform a dancing act. He stumbles and falls on the stage during his entrance. Rosita encourages him, but his steps are uncoordinated. “Faster, dance faster”, Rosita coaches him from the wings. But setting his speed control in back faster just renders him out of control, and he gets a tomato in the face and is dragged off by a theatrical “hook” to the Watch-pital. Rosita remains to answer her cue, and performs a tight-wire act. For no apparent reason except storytelling convenience, she misses her step and falls to the stage, with a tiny glass tinkle heard. She is taken to the emergency room of the Watch-pital, where two older clocks shake their heads, noting that she has stopped ticking. Between them enters the pocket watch. “Stand back! I’m a doctor’s watch,” The film here borrows heavily from the idea of Van Buren’s Grandfather’s Clock, discussed earlier in these articles, as, taking charge of the situation, the pocket watch opens Rosita’s back, and performs an emergency operation, replacing jewels, mainspring, and finally, balance wheel (again shaped like a heart as in Van Buren’s cartoon). The wheel goes back and forth a few times, but stops. “Tick to me, tick to me”, he cries. As he is about to give up hope, a faint tick is heard – and Rosita revives. She plants a grateful kiss on the pocket watch, and everyone cheers. The film abruptly ends with stock wraparound footage to get the kids back to the surface – never resolving how the romance is going to survive if Rosita’s still in the Big Time and the pocket watch still in the Watch-pital. Write your own ending.

Disney’s Peter Pan (Disney/RKO, 2/5/53) features, without much in the way of unusual plot complications, another time bomb, planted by Captain Hook in Peter Pan’s hideout at Hangman’s Tree and disguised as a surprise package from Wendy. Tinker Bell, who was tricked by Hook into revealing Peter’s hiding place, nearly sacrifices herself to save Peter, flying the bomb away from him as it explodes. The film also of course features the short iconic shot of Pan, Wendy and her brothers getting their bearings on their trip to Never Land while standing on the hands of Big Ben.

Sock-a-Doodle Do (Warner, Foghorn Leghorn, 5/10/52 – Robert McKimson, dir.), features one surprise gag involving a clock. A champion fighting bantam rooster (voiced by (Sheldon Leonard) has wandered into the barnyard world of Foghorn and his arch rival, Barnyard Dawg. The little champ is quite punchy, and at the sound of any kind of bell comes out fighting – a trait which both Foggy and the Dawg learn to use to full advantage – against each other. At one point, Dawg presents the bantam with a gift-wrapped package to take over to Foghorn. Hearing that the package from Dawg is intended as a gift for him, Foghorn pushes the bantam away from the package, saying “Stand back, boy! Ir’s probably a booby trap!” Cautiously pulling away the wrapping, the contents of the package are revealed to be a Tyrolean clock, with an animated figure in lederhosen who emerges carrying a little bell – which he strikes with a hammer. The bantam instantly springs into action, socking Foghorn so hard, his head submerges into his abdomen, with only his beak visible. “I was right”, Foghorn attests weakly, “It was a booby trap.”

Sock-a-Doodle Do (Warner, Foghorn Leghorn, 5/10/52 – Robert McKimson, dir.), features one surprise gag involving a clock. A champion fighting bantam rooster (voiced by (Sheldon Leonard) has wandered into the barnyard world of Foghorn and his arch rival, Barnyard Dawg. The little champ is quite punchy, and at the sound of any kind of bell comes out fighting – a trait which both Foggy and the Dawg learn to use to full advantage – against each other. At one point, Dawg presents the bantam with a gift-wrapped package to take over to Foghorn. Hearing that the package from Dawg is intended as a gift for him, Foghorn pushes the bantam away from the package, saying “Stand back, boy! Ir’s probably a booby trap!” Cautiously pulling away the wrapping, the contents of the package are revealed to be a Tyrolean clock, with an animated figure in lederhosen who emerges carrying a little bell – which he strikes with a hammer. The bantam instantly springs into action, socking Foghorn so hard, his head submerges into his abdomen, with only his beak visible. “I was right”, Foghorn attests weakly, “It was a booby trap.”

The Clockmaker’s Dog (Terrytoons/Fox, January, 1956 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – A well made and atmospheric Terrytoon, cross-pollenating some obvious influences from Disney’s “Pinocchio” with additional influences from MGM’s “Little Caesario” (8/30/41). The opening sequence plays like some leftover shots from the Gepetto clock sequence of Disney’s epic, animated about as well as Terry’s budgetary constraints could permit. A first clock opens curtains on a ballerina figure, with two ardent observers watching the performance from respective balconies – the time is chimed in by her high kicks, which catch each of the balcony boys square in the chin. A second clock lifts an idea from a set of mechanical figures used in Donald Duck/Chip ‘n’ Dale’s Christmas classic, Toy Tinkers (1950) – a pair of gentlemen with dueling pistols, each with a flag that says “Bang”, alternate shooting each other down. A third clock has a fat lady emerge from a windmill and bend over to pick a flower, while a goat emerges behind her and butts her every time she bends. The clocks vanish from center stage for a while, focusing on the clockmaker’s pet Fritzie, who, despite being small in size, wants to join the alpine St. Bernards. He sneaks out one day, and attempts to try out at the monastery – but can’t even handle the brandy barrels, which are almost bigger that Fritzie himself. Meanwhile (in another inspiration from “Pinocchio”, mirroring the scene of Gepetto searching for the puppet, the clockmaker looks for lost Fritzie in the hills – and stumbles off a ledge, suspended only by his mountain climbing pick. The St. Bernards answer the rescue call on skis, while Fritzie makes his own small skis out of slats of his broken brandy barrel. Fritzie manages to trip-up on a ski jump and start rolling into a snowball, getting ahead of the St. Bernards and intersecting the path of his master just as he falls from the ledge. The snowball slowly rolls to a stop and splits down the middle, releasing the clockmaker and Fritzie for a happy reunion. Fritzie is decorated by the St. Bernards for his valor. And the clockmaker wins first prize for a new clock design – framed by St. Bernards, with a splitting snowball, inside which a mechanical version of his little dog pours brandy down the throat of his rescued master.

Calling All Cuckoos (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 9/24/56 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – A typical assortment of overly broad, brash, and often quite predictable Paul Smith violence gags served up in heaping proportions, on an odd premise. Herr Spring, a Germanic clockmaker, labors in his Black Forest workshop on a new cuckoo clock, amidst several walls full of his past creations. 9:00 chimes, and he applies earplugs while cuckoo birds emerge in noisy chorus. The odd part is that while all the other cuckoo birds look identical and mechanical, Herr clockmaker gets the notion to hunt for a live cuckoo to inhabit his latest clock. Flimsy storytelling, what? But then, most Smith episodes were mere setups for gags rather than real stories (with rare exceptions such as The Flying Turtle (1953)). In another weak plot point, Woody Woodpecker is drawn into the hunt, masquerading as a cuckoo without any more motivation for same than sheer boredom and to have fun with a “nut”. Story man Homer Brightman is probably equally to blame, falling back on what became a repetitious formula for many of his Lantz scripts – the recurring appearance of some third character as either a figure of authority or of threat to menace the hero’s adversary. This time, such figure appears in the form of a bear, who Woody repeatedly draws into the festivities to be a fall guy for Herr Spring’s cuckoo traps. The bear has only one reaction – grab the nearest club, and bash the clockmaker repeatedly in the head – a gag that gets tired fast.

To make matters short, Woody is eventually put to work in a clock – with no supper, yet. Of course, this doesn’t stop him from appearing on the hour, and swiping the clockmaker’s hamburger. Woody does the old, appear-randomly, and simultaneously, inside of every clock routine, with the clockmaker turning every clock face to the hour to try to get him out. Every emergence is another violent gag – mallets falling, cymbals smashing, tubas blasting, fire hoses squirting, and even a stray chicken placed in one clock to lay an egg on him (just like this whole cartoon is doing). Finally, 12:00 approaches, and clockmaker runs for the earplugs again. But Woody pushes the sleeping bear into the room, with no earplugs. The rude awakening prompts the bear to finally abandon his trusty club, and smash a cuckoo clock over the clockmaker’s head. Woody emerges on its cuckoo platform for a “Ha-Ha-Ha-Cuckoo!” final fadeout.

A few historical notes. In a case of being a poor judge of horseflesh, Lantz made the tasteless decision to submit this film for consideration for the Academy Awards (covered in an extensive series of past Cartoon Research articles under the “Animation History” banner on this website), even though, unlike Marlon Brando’s famous line, Lantz should have known that this film never “coulda been a contender”. The film was further oddly kept alive for years in the Castle Films home movie catalog, which, in view of already being flooded with a variety of Woody Woodpecker titles, made no reference to Woody being in the picture at all – instead marketing the film under the series banner “Pierre Bear” (a generic category Castle used to include any miscellaneous Lantz cartoon in which a bear appeared, despite the fact that the real Pierre only appeared in one Woody short, After the Ball (1956)). But this was the kind of short Castle loved, particularly for use in its 50 foot “Headliner” editions – lots of short gags in rapid fire succession, so it looked like you were cramming a lot of action into a two-and-a-half minute reel.

A few historical notes. In a case of being a poor judge of horseflesh, Lantz made the tasteless decision to submit this film for consideration for the Academy Awards (covered in an extensive series of past Cartoon Research articles under the “Animation History” banner on this website), even though, unlike Marlon Brando’s famous line, Lantz should have known that this film never “coulda been a contender”. The film was further oddly kept alive for years in the Castle Films home movie catalog, which, in view of already being flooded with a variety of Woody Woodpecker titles, made no reference to Woody being in the picture at all – instead marketing the film under the series banner “Pierre Bear” (a generic category Castle used to include any miscellaneous Lantz cartoon in which a bear appeared, despite the fact that the real Pierre only appeared in one Woody short, After the Ball (1956)). But this was the kind of short Castle loved, particularly for use in its 50 foot “Headliner” editions – lots of short gags in rapid fire succession, so it looked like you were cramming a lot of action into a two-and-a-half minute reel.

Though the prop itself was never played to provide its own sight gag, a time clock provided a central and recurring theme throughout Chuck Jones’ Sam Sheepdog and Ralph Wolf series (the sort of second cousins to Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner). Throughout the run of these films, Sam and Ralph were depicted as blue-collar workers who took their respective “professions” highly seriously – and punched in right on time as all dedicated workers do on the clock. Amazingly, off the clock, they were usually cast as casual friends – but when the 9:00 whistle blew, they would spend the entire work day as mortal enemies. Though we never knew precisely who they were working for (as no “boss” ever appeared), Sam and Ralph were presumably on payroll from someone, so made a point to keep their regular hours. Sometimes not knowing who employed them could add to the humor. In some cases, each punched in on a different time clock – suggesting that there must be a wolf denizen’s corporation to rival the sheep protective society presumably employing Sam. In other instances, both would punch in on the same clock – suggesting the even funnier idea that one organization would spend money to raise sheep while simultaneously employing carnivores to eat them!

Sometimes Sam and Ralph appeared to be the only employees. Other times, they would be part of a larger crew, with another sheepdog and wolf punching in at the end of their shift to pick up taking a beating where the first two had left off at the five o’clock whistle. The whistle for quitting time would sometimes be a negative factor for Ralph – such as preventing him from getting the chance to detonate a circle of missiles and explosive devices around Sam, leaving Sam to comment “Better luck next time.” Other times, it would be a saving grace, as where Ralph has just discovered a hidden firecracker within a sheep costume, but before it goes off, Sam extinguishes it, saying “It’s too close to quitting time. We’ll pick it up there in the morning”, then wishes his pal “Pleasant dreams” as he departs – dreams no doubt, of being blown up come the dawn. Possibly the oddest ending of all had the two of them heading home after punching out, with Ralph battered and limping, while Sam remarks, “You’ve been working too hard, Ralph. Why don’t you take tomorrow off? I can handle both jobs.” We can only imagine the spectacle of watching Sam inflicting grievous bodily harm upon himself for the entire 9 to 5 shift.

Sometimes Sam and Ralph appeared to be the only employees. Other times, they would be part of a larger crew, with another sheepdog and wolf punching in at the end of their shift to pick up taking a beating where the first two had left off at the five o’clock whistle. The whistle for quitting time would sometimes be a negative factor for Ralph – such as preventing him from getting the chance to detonate a circle of missiles and explosive devices around Sam, leaving Sam to comment “Better luck next time.” Other times, it would be a saving grace, as where Ralph has just discovered a hidden firecracker within a sheep costume, but before it goes off, Sam extinguishes it, saying “It’s too close to quitting time. We’ll pick it up there in the morning”, then wishes his pal “Pleasant dreams” as he departs – dreams no doubt, of being blown up come the dawn. Possibly the oddest ending of all had the two of them heading home after punching out, with Ralph battered and limping, while Sam remarks, “You’ve been working too hard, Ralph. Why don’t you take tomorrow off? I can handle both jobs.” We can only imagine the spectacle of watching Sam inflicting grievous bodily harm upon himself for the entire 9 to 5 shift.

Many storyteller children’s records were adapted for use as soundtracks for a limited-animation series of television shorts around 1960 knowm as Mel-o-Toons. As a Christmas treat, I can’t resist bringing up two records that somehow missed the cut for this series, yet sounded for all purpose like ready-made soundtracks in search of a cartoon. Tickety Tock (the Clock That Couldn’t Tell Time) (Capitol EAS 3016), featured story by Warner veterans Warren Foster and Tedd Pierce, narration by Knox Manning (frequent narrator for Warner Brothers live action shorts and Columbia serials), and character voicing by Arthur Q. Bryan (voice of Elmer Fudd) and Pinto Colvig (voice of Goofy, Practical Pig, Gabby, etc.) A little alarm clock disrupts nightly “orchestra” practice among clocks in a clock store by ringing at inopportune moments during a “Clock Symphony” – because he’s never learned how to tell time, and his alarm goes off at random uncontrollably. Part of the problem is that a little boy once took him apart with a screwdriver, and didn’t quite reassemble him right. An unknowing farmer purchases him one day, and sets Tickety to wake him early in the morning. Tickety ponders how to figure when to ring, coming up with a complex mathematical calculation of how many ticks will be needed between now and morning, and starts counting his ticks. But one of his uncontrollable rings comes on hours before schedule. The frustrated farmer tosses the “no-good” contraption out the window. As Tickety lays in the field, he spots a red glow coming from the farmer’s barn – a fire breaking out. Realizing his alarm could finally be of use, Tickety sprains his mainsprings with all his might, until he finally feels another ring about to burst forth. The ringing rouses the farmer in the nick of time to look out the window, and ultimately save the barn. As a reward, the farmer has Tickety professionally repaired, and with his new found mathematical abilities, Tickety assumes a position of honor as the farmer’s dependable timekeeper.

The Clock That Went Tock-Tick (Admiral K-206 A), was a recording that made the rounds, reissued several times on Peter Pan, Rocking Horse, Tinkerbell, and possibly even Coral records. With some anonymous help from a secondary voice as a grandfather’s clock, the story is almost entirely performed and narrated by animation veteran and on-camera comedian Arnold Stang (Herman the Mouse, Top Cat). A similar plotline to “Tickety Tock” has Stang as a newcomer clock to a clock store – except he’s got his ticks and his tocks mixed up, so he runs backwards. He hears the other clocks, and thinks they’re the ones that are confused. He attempts to stand up to their chorus of “tick tocks” by attempting to drown them out with the loudest “tock ticks” possible, causing a commotion in the store. The grandfather’s clock takes charge, putting Stang in his place, and announcing that if he doesn’t stop it, grandfather will see that they get an electric clock to take his place. The thought of such replacement sends shivers of fright through the little clock – who develops a case of nervous hiccups. Finding himself saying “Hic-tock” instead of “tock tick”, Stang starts running forwards – and catches up on time with the other clocks. With a little practice, he converts his “hic-tocks” to tick-tocks”, and becomes so dependable that he gets the job as the clock in the President’s office (though occasionally he still lapses into a random hiccup instead of a tick).

Both such records were a genuine delight, and entertained me frequently in my youth. They deserve rediscovery. Though of more marginal relationship to the subject of this article, a later recording, “James Bomb” (Hanna-Barbera Records HLP-2036 (1966)), plays like a prime-time special for Super Snooper and Blabber Mouse, featuring Daws Butler and Don Messick in their prime, as the cat-and-mouse detectives get unwittingly recruited as messengers for a time bomb, and team up with an ersatz Agent 007 to foil the nefarious plans of Dr. Oh No and Gold Pinky. I often wished H-B had remembered this script, one of the best of their record projects, when they started producing movie length vehicles for some of their animated superstars in the 1980’s, and found a way to commit it to film. It’d be tempting to storyboard it, as I’ve seen it so many times in my own “theater of the mind.”

Though we’re all about time here, I’ll take the liberty of reviewing one item out of chronological order – since it’s just in time for the Christmas season. Rankin-Bass’s Twas the Night Before Christmas (12/8/74). Keeping the budget down a bit by producing this half-hour special in 2D cel animation rather than stop-motion, the studio gets to marshal its assets for some reasonable writing, a few decent songs, and a solid voice cast including Joel Grey (“Cabaret”), Tammy Grimes (“The Unsinkable Molly Brown”), and master of underplayed comedy George Gobel (who we only wish had been allowed to cut loose in his own personal style instead of having to stick to a script. Oh, well, he needed the work.) The plot, which eventually leads up to a four-minute or so retelling of the famous poem, is a bit unusual, in that (without any actual opportunity to explore the character’s motivations and temperament from a personal firsthand view) we are apparently presented with a Santa with a somewhat vengeful streak – willing to place a whole town on the naughty list until he receives an appropriate apology. All over town, every letter the townsfolk sent to Santa this year is being returned by the post office, stamped, “Not accepted by Addressee.” No one knows why, until a mouse clockmaker’s assistant (Gobel) calls long distance to a switchboard station at the North Pole, and gets a tip that it has something to do with a “letter to the editor” that recently published in the local paper.

A denouncing letter is located in the back issues, declaring Santa to be a fraud and a hoax that no one believes in, anonymously signed by “All of Us.” The writing style’s use of “long words” seems all too familiar to Gobel – who tracks down the culprit right in his own home – his overly-educated “brain-boy” of a son (Tammy Grimes), who has taken it upon himself to act as the self-appointed “voice of wisdom” to debunk the Santa Claus myth. Gobel’s human boss, the clockmaker (Grey) also has a family of kids facing disappointment. Realizing independently that Santa’s angry at something, Grey designs a special tower clock which he proposes to the City Counsel to build before Christmas, with a massive loudspeaker mechanism to play a song of greeting and apology at precisely midnight on Christmas Eve when Santa is in the air, in hopes that Santa can be coaxed to place the town back into his good graces. The city approves the plan. Meanwhile, Gobel tries to show his son the unhappiness he’s spread by forcing his beliefs upon everyone, and that other people feel differently and should be entitled to different opinions and hope for the holidays. Grimes begins to soften and understand. Gobel points out how his boss is doing everything to make amends to Santa, and tells Grimes of the clock tower construction. Grimes’ inner braniac is intrigued with a desire ti see how this invention operates firsthand.

A denouncing letter is located in the back issues, declaring Santa to be a fraud and a hoax that no one believes in, anonymously signed by “All of Us.” The writing style’s use of “long words” seems all too familiar to Gobel – who tracks down the culprit right in his own home – his overly-educated “brain-boy” of a son (Tammy Grimes), who has taken it upon himself to act as the self-appointed “voice of wisdom” to debunk the Santa Claus myth. Gobel’s human boss, the clockmaker (Grey) also has a family of kids facing disappointment. Realizing independently that Santa’s angry at something, Grey designs a special tower clock which he proposes to the City Counsel to build before Christmas, with a massive loudspeaker mechanism to play a song of greeting and apology at precisely midnight on Christmas Eve when Santa is in the air, in hopes that Santa can be coaxed to place the town back into his good graces. The city approves the plan. Meanwhile, Gobel tries to show his son the unhappiness he’s spread by forcing his beliefs upon everyone, and that other people feel differently and should be entitled to different opinions and hope for the holidays. Grimes begins to soften and understand. Gobel points out how his boss is doing everything to make amends to Santa, and tells Grimes of the clock tower construction. Grimes’ inner braniac is intrigued with a desire ti see how this invention operates firsthand.

At the unveiling of the new clock tower, Grey, after a ribbon-cutting ceremony, attempts to demonstrate the clock in action. Instead of music, the clock starts emitting sprung springs and popped gears, and completely malfunctions. Grey is disgraced, and the mayor bans him from even touching the clock to attempt repairs. Gobel suspects something, and questions his boy. Sure enough, his son couldn’t resist curiosity, and had gotten into the clock tower before the unveiling, accidentally disrupting the mechanisms. Grimes is finally truly repentant, and while Gobel states it’s all too late to do anything now to save the holiday, Grimes retrieves a book about Copernicus – the father of clockwork – and insists that he’ll use it to find a way to right his wrong. As the hour of midnight approaches, Grimes sneaks inside the clock tower again and works feverishly amidst the massive gears. Gobel confesses to Grey his son’s involvement in the unveiling fiasco, and informs him that his son is trying to make amends. They wait…and wait…and a clock in the room chimes twelve – but no song outside. As they are about to give up hope – half a minute late – the music rings out! Santa, almost past the town, but hears the music at last, relents, and turns his team around to deliver presents to the town’s children. Inside the clock tower, Grimes cavorts in happy glee among the gears, and, together with the rest of the townsfolk, discovers the joy of greeting the real Santa. Not a bad storyline. While directing could have been stronger, animation was reasonably good for a Rankin-Bass production (with the exception of Santa, who would have been much better if they’d just retained the old model sheet from “Frosty the Snowman”). Not Rankin-Bass’s most classic production, but certainly far from its worst.

Time is running out! One week left for the old year – and this topic. We’ll compress time to cover the television era from the 60‘s through the 90’s – as well as highlight theatrical timepieces appearing in the last theatrical shorts and a high-tech feature. Plus some brief interludes for those time=keepers that don’t reside on a wall or in a tower. Happy Holidays, and thanks for spending the time to be with us.

NEXT WEEK: 5 – – 4 – – 3 – – 2 – – 1……………….

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

In discussing Peter Pan, you forgot the one clock taken from the original novel and play – the one inside the crocodile who is always after Captain Hook, making his presence known by the tic-toc that provides the rhythm section for Frank Churchill’s leitmotif “Never Smile at a Crocodile”. Both Hook’s face and the croc’s eyes twitch in time to the clock for an amusing running gag. Of note is the scene near the end when Hook escapes being swallowed and comes out with the clock in his hands, only to throw it back at the croc, who swallows it yet again.

Those are some charming stories, and I especially like the “Clock Symphony”. (One of Haydn’s symphonies, No. 101 in D major, is nicknamed “The Clock” for its constant ticking rhythm in the second movement.) But I find Arthur Q. Bryan’s rhotacism as the uncontwowabwy winging awawm quock — that is, the uncontrollably ringing alarm clock — just a little distracting.

I have a vivid recollection of a suspenseful countdown in an Astro Boy episode that I have not seen in at least half a century. Astro Boy had just sixty seconds to save the day; we were continually reminded of this because Dr. Pachydermus J. Elefun kept announcing how much time was left. There was even a ticking clock suspended over his head, or possibly even growing out of it, to heighten the suspense. I also recall that those sixty seconds occupied about half the episode in real time, and the ticking seconds got longer and longer as they went by; Astro Boy still had about half a minute to defeat the whatevers after Dr. Elefun shouted “One second left!” Thus time passed more slowly the longer it dragged on. I would later notice this phenomenon in school, church, visits to elderly relatives, etc.

Perhaps this would be more appropriate in next week’s post about the TV era; but, knowing your antipathy toward superhero cartoons, I fear it might get overlooked. If any readers have additional info on this Astro Boy episode, or better still a link to it, I will be most grateful!

A sort-of cartoon clock: As I recollect, “Rescuers Down Under” and “Mickey’s Christmas Carol” were released together with a ten-minute “Intermission” connecting them. The intermission show was a piece of a clock face, the hand moving after each one-minute instrumental of an old Disney song.

You may be thinking of Mickey’s The Prince and The Pauper, which ran with Rescuers Down Under. When I went to see it in the theater, they didn’t ran the intermission clock.

I didn’t see it, but when the first two Toy Story movies were rereleased in 3-D, there was an intermission. Anyone saw that, and was there a clock there too?

Love these themed cartoon posts! I’m sure it will be mentioned, but one clock-related gag in a TV cartoon is, of course, Bullwinkle’s recitation of “Hickory-Dickory-Dock”, with the little mouse out to foil the moose and the rhyme at every turn. I won’t give away the terrific punchline. Christmas is coming to a close here, and I wish you all a terrific and emphatically prosperous New Year. We need good news on classic cartoons in 2020, even though there will only be 100th birthdays to some silent cartoons. Hey, these need restoration most of all!! Good luck to us all in the forthcoming years ahead.

I hadn’t actually included any discussion of “Bullwinkle’s Corner” bits, as I’ve forgotten a lot of them and tend to think of them as interstitials. I looked up your suggestion and remembered it after seeing it again. It fits. But there’s another one I ran across you didn’t mention: “Grandfather’s Clock”, in which Bullwinkle explains to Rocky that the clock didn’t really stop running when Grandfather died – it only stopped yesterday when Grandfather went missing – but that doesn’t rhyme so good! Rocky suggests opening the clock, and they find Grandfather stuck inside it. Bullwinkle laughs at how anyone can get stuck in a clock, and Grandpa shows him how – by kicking him right through it. “Now there’s something you don’t see everyday”, Gramps tells Rocky, “A clock with a face on both sides.”

Also, don’t forget Bullwinkle’s wrist-hourglass at the end of the show, which he compares with Rocky’s big one, with interchangeable dialog lines, “Mine must be a little slow” or “Just enough left to tell them who the sponsor was.”

Even Hoppity Hooper had a clock ending, where he’d hop over to a cuckoo clock and say “Looks like it’s time for us to go.” Filmore Bear pops his head out of the clock and blows his bugle. Hoppity, in disgust, says to the audience, “Now I’m sure it is!”

Hi there! I just discovered your remarkable website. So many interesting reads. Can you, or perhaps one of your readers, tell me the name of a cartoon I’ve been hunting for? I believe it was a vintage Tom & Jerry, but I could be mistaken. Jerry Mouse falls in love with the little Swiss figurine from a cuckoo-like clock. Any leads would be most appreciated!

I’m afraid I can’t think of any cartoon that exactly matches your description. There are several Tom and Jerry cartoons that feature cuckoo clocks, notably “Dog Trouble” (1942) but also “Designs on Jerry” (1955) and “The A-Tom-inable Snowman” (1966). However, those clocks don’t have any love interests for Jerry, only cuckoos.

There’s a chance you may be thinking of “Mouse Trouble” (1944), in which Tom baits Jerry with a cute mechanical girl mouse who utters Mae West’s catchphrase “Come up and see me sometime!” Jerry is instantly smitten, and he and his date walk arm in arm to the façade of a hotel, behind which Tom is hiding. But when Jerry, ever the gentleman, allows his girl to enter first, Tom swallows her instead. At the end of the cartoon, when Tom, having blown himself up with his own explosives, is in Heaven with a halo and harp, the mechanical mouse is still repeating “Come up and see me sometime!” from inside his stomach — and he’s not happy about it at all!

The theme of Tom using a clockwork girlfriend to seduce Jerry would be repeated in “New Mouse in the House” (1980) from Filmation’s New Adventures of Tom and Jerry, which is really terrible, and “Hi, Robot” (2007) from Warner Bros.’ Tom and Jerry tales, which is actually pretty good. Both times, of course, the scheme backfires on Tom.

Then again, you might be remembering the scene in “Pinocchio” where Jiminy Cricket flirts with the mechanical Swiss girl in a cuckoo clock in Geppetto’s workshop….