1942 is our subject year. Many films from this period keep their self-referential elements on the brief side, so some of the discussions below are a little briefer than usual also, providing light reading this week. As Tex Avery was in transition between studios, his work appears only once in this latest survey. However, his influence on breaking the fourth wall and characters being aware of their screen existence continues to overflow to other studios, particularly inspiring an entry by Walter Lantz appearing below. Also, another rare live-action animation crossover from Warner Brothers, and a double-dose of Bugs Bunny, continuing to demonstrate he is well aware of who he is talking to when he shares with us his seven minutes or so on the screen.

Fleets of Stren’th (Famous/Paramount, Popeye, 3/13/42 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Al Eugster/Tom Golden, anim.) – As previously documented in earlier article of this trail, Popeye was from the beginning conscious of his screen existence and co-existence in the medium of print. He begins this episode by showing he is also conscious of and closely following the competition in both mediums. In his new outfit of navy white, as a member of the enlisted services of WWII, he scrubs the deck of a battleship, while simultaneously secretly passing the time reading the comics of Superman. (This move was obviously an instance of shameless cross-promotion of Fleischer’s new film franchise – but perhaps may also have served the dual purpose of answering the obvious question that may have arisen from various Popeye fan clubs, what with Fleischer having two supernaturally-strong characters on his batting card. What would Popeye think of Superman, and which of the characters was the strongest? Popeye answers these inquiries with under-the breath mumbling to himself as he reads Superman’s adventure. “That Superman is pretty good. Well, I can’t be as strong as Superman and handsome, too.” A call of “Attention” from the Captain snaps Popeye to his feet, as he quickly folds up the comic with some fancy footwork into a tight packet to avoid its discovery by the Captain.

Fleets of Stren’th (Famous/Paramount, Popeye, 3/13/42 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Al Eugster/Tom Golden, anim.) – As previously documented in earlier article of this trail, Popeye was from the beginning conscious of his screen existence and co-existence in the medium of print. He begins this episode by showing he is also conscious of and closely following the competition in both mediums. In his new outfit of navy white, as a member of the enlisted services of WWII, he scrubs the deck of a battleship, while simultaneously secretly passing the time reading the comics of Superman. (This move was obviously an instance of shameless cross-promotion of Fleischer’s new film franchise – but perhaps may also have served the dual purpose of answering the obvious question that may have arisen from various Popeye fan clubs, what with Fleischer having two supernaturally-strong characters on his batting card. What would Popeye think of Superman, and which of the characters was the strongest? Popeye answers these inquiries with under-the breath mumbling to himself as he reads Superman’s adventure. “That Superman is pretty good. Well, I can’t be as strong as Superman and handsome, too.” A call of “Attention” from the Captain snaps Popeye to his feet, as he quickly folds up the comic with some fancy footwork into a tight packet to avoid its discovery by the Captain.

The remainder of the film has no particular cartoon self-awareness, but is a moderately spectacular action-adventure, as Popeye fights impossible odds, virtually single-handed. The Captain insists that the Navy requires discipline, and puts Popeye through a grueling close-order drill, then leaves him with a final command that freezes Popeye standing at stiff attention. Suddenly, an aerial attack begins, as a carrier fighter plane begins strafing the deck and dropping payloads of bombs on and around the ship. Popeye continues to follow the last command, rigidly standing as the deck vibrates from explosions, and a bomb drops inches from Popeye’s toes, blasting the sailor to the top of the mainmast, where he still stands at attention. The Captain finally relieves him, with a shout of “What are you standing there for? Get that plane”. “She’s as good as got”, responds Popeye, swinging down the ship’s rigging, and taking off after the plane in a machine-gun armed mosquito boat. A seemingly endless armada of planes begins to rise from the deck of a carrier. One catches Popeye’s feet in its propeller blades, while Popeye desperately tries to hang onto the ship’s wheel, twisting him around in a braid. Another dives so low, Popeye has to jump and run over the top of the plane to avoid collision. A third alternates between high and low tracer fire with its machine guns, causing Popeye to impossibly compress himself to stay between the lines of fire. Then, a series of planes passes over him, dipping their tails down to bash Popeye in the head with their elevator and rudder panels. Yet another plane, with remarkably flexible pontoon landing gear, grabs hold of Popeye’s mosquito boat between its pontoons, and crushes the vessel like it was a matchbox, dumping Popeye into the ocean. Two planes approach from either side, both dropping torpedoes in Popeye’s direction. Popeye is contemplating his spinach, but doesn’t have time to open the can, instead ducking under the water to let the torpedoes collide with each other.

The remainder of the film has no particular cartoon self-awareness, but is a moderately spectacular action-adventure, as Popeye fights impossible odds, virtually single-handed. The Captain insists that the Navy requires discipline, and puts Popeye through a grueling close-order drill, then leaves him with a final command that freezes Popeye standing at stiff attention. Suddenly, an aerial attack begins, as a carrier fighter plane begins strafing the deck and dropping payloads of bombs on and around the ship. Popeye continues to follow the last command, rigidly standing as the deck vibrates from explosions, and a bomb drops inches from Popeye’s toes, blasting the sailor to the top of the mainmast, where he still stands at attention. The Captain finally relieves him, with a shout of “What are you standing there for? Get that plane”. “She’s as good as got”, responds Popeye, swinging down the ship’s rigging, and taking off after the plane in a machine-gun armed mosquito boat. A seemingly endless armada of planes begins to rise from the deck of a carrier. One catches Popeye’s feet in its propeller blades, while Popeye desperately tries to hang onto the ship’s wheel, twisting him around in a braid. Another dives so low, Popeye has to jump and run over the top of the plane to avoid collision. A third alternates between high and low tracer fire with its machine guns, causing Popeye to impossibly compress himself to stay between the lines of fire. Then, a series of planes passes over him, dipping their tails down to bash Popeye in the head with their elevator and rudder panels. Yet another plane, with remarkably flexible pontoon landing gear, grabs hold of Popeye’s mosquito boat between its pontoons, and crushes the vessel like it was a matchbox, dumping Popeye into the ocean. Two planes approach from either side, both dropping torpedoes in Popeye’s direction. Popeye is contemplating his spinach, but doesn’t have time to open the can, instead ducking under the water to let the torpedoes collide with each other.

The explosion blows Popeye high into the air, where a plane zeroes in with its machine gun fire. Now Popeye gets the spinach can open, by letting the bullets do the work for him, cutting into the can lid like an opener. His pipe spinning and arms outstretched, Popeye zooms through the air, momentarily transformed into the image of a four engine heavy fighter. As the enemy plane continues to shoot, Popeye catches the bullets in his bare hands, swallows them, then shoots them out his mouth, carving away the enemy’s prop to send it into a crash dive. Popeye grabs the tails of two more planes and ties them together, so that their engines pull each other’s fabric off, exposing the planes’ bare metal framework. Popeye next performs a trapeze act from one plane’s landing gear to another to another, removing the props off two of them, and turning the third upside down. Standing on the belly of the inverted plane, Popeye performs a juggling act with three aerial bombs dropped to him, then tosses the bombs back for direct hits on the planes that threw them, set to the notes of the NBC chimes. A new round of ten fighters launches from the flight deck, and Popeye repeats his old bit from “Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves”, taking a spare aerial bomb, pitching it through the air, and scoring a bowling strike on the squadron. These last planes fall back to the deck of the carrier, engulfing the ship in black explosion clouds. The final shot shows Popeye using a mast as a giant rowing oar, aboard the bow of the bombed-out hulk of the carrier, rowing it back to his ship as a war prize, with visible holes in the front bow in the shape of a V and a dot dot dot dash, synonymous with the key notes of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony that became a call for victory throughout the wartime years.

The explosion blows Popeye high into the air, where a plane zeroes in with its machine gun fire. Now Popeye gets the spinach can open, by letting the bullets do the work for him, cutting into the can lid like an opener. His pipe spinning and arms outstretched, Popeye zooms through the air, momentarily transformed into the image of a four engine heavy fighter. As the enemy plane continues to shoot, Popeye catches the bullets in his bare hands, swallows them, then shoots them out his mouth, carving away the enemy’s prop to send it into a crash dive. Popeye grabs the tails of two more planes and ties them together, so that their engines pull each other’s fabric off, exposing the planes’ bare metal framework. Popeye next performs a trapeze act from one plane’s landing gear to another to another, removing the props off two of them, and turning the third upside down. Standing on the belly of the inverted plane, Popeye performs a juggling act with three aerial bombs dropped to him, then tosses the bombs back for direct hits on the planes that threw them, set to the notes of the NBC chimes. A new round of ten fighters launches from the flight deck, and Popeye repeats his old bit from “Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves”, taking a spare aerial bomb, pitching it through the air, and scoring a bowling strike on the squadron. These last planes fall back to the deck of the carrier, engulfing the ship in black explosion clouds. The final shot shows Popeye using a mast as a giant rowing oar, aboard the bow of the bombed-out hulk of the carrier, rowing it back to his ship as a war prize, with visible holes in the front bow in the shape of a V and a dot dot dot dash, synonymous with the key notes of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony that became a call for victory throughout the wartime years.

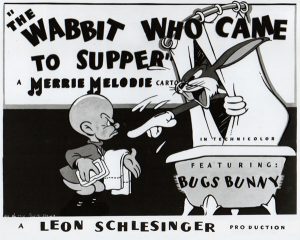

The Wabbit Who Came To Supper (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 3/28/42 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – A basic plot setup which would soon be borrowed and embellished upon by Hanna and Barbera a mere few years later in “The Million Dollar Cat”. In the middle of a rabbit hunt, Elmer Fudd receives a telegram (amazing how these messenger boys can track him down in the middle of the woods). The message indicates Elmer’s Uncle Louie is leaving him three million dollars in his will – “But you don’t get one cent if you harm any animals – especially rabbits.” The hunt is immediately called off, but Bugs isn’t about to ignore a setup like this. Before you know it, he’s moved in on the Fudd abode, taking full advantage of the bathroom facilities (including a suspect cel which has been frame-grabbed on several sites, possibly showing Bugs with more between his legs than just a bath towel), and demanding to be waited on for dinnaer. Elmer pulls a fast one, opening a door and inviting Bugs to “Step wight this way”. Bugs walks through, finding it is an exit to the porch, and has the door slammed behind him. Bugs pounds on the door, demanding to be let back in – then changes tactics, lapsing into a fake death scene reminiscent of the finale of “A Wild Hare”, claiming that he is dying of pneumonia from the night air. In the midst of his coughs and pathetic gasps for air, Bugs breaks the fourth wall, addressing the audience: “Hey, this scene ought to get me the Academy Award!” As Bugs gasps, “Say goodbye to Uncle Louie for me”, the door flies open, and Elmer realizes he is trapped by the rabbit’s game. Bugs is carried back in, and even rocked to sleep with a lullaby (in swing tempo) in Elmer’s arms. (Note this and other scenes for multiple backgrounds in which Freleng engages for possibly the first time in a game he and his crew would indulge in as a lark from time to time, to see just how much could be slipped past the censors without notice – the placement of various “art nudes” in frames on the wall, often in backgrounds that would linger for a considerable length of time on the screen. In some later productions, Freleng had to be slightly more subtle in pulling this off, choosing to place the paintings in backgrounds that rapidly panned across the screen, so that the images were only visible for a few frames at a time.) A telegram arrives at the front door. Uncle Louie has kicked the bucket – but an inventory of taxes has devoured the entire inheritance, and exceeded it, “Which leaves you owing us $1.98. PLEASE REMIT.” After a chase, Bugs is quickly ousted – followed by another messenger delivery. From an unknown sender comes a giant “Easter greetings” in the form a huge egg. The egg pops open, revealing contents of several dozen rabbits, slightly smaller than Bugs, who greet Elmer in a unison, “Eh, what’s up, doc?”, and proceed to hop all over the place, taking over Elmer’s home once again.

The Wabbit Who Came To Supper (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 3/28/42 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – A basic plot setup which would soon be borrowed and embellished upon by Hanna and Barbera a mere few years later in “The Million Dollar Cat”. In the middle of a rabbit hunt, Elmer Fudd receives a telegram (amazing how these messenger boys can track him down in the middle of the woods). The message indicates Elmer’s Uncle Louie is leaving him three million dollars in his will – “But you don’t get one cent if you harm any animals – especially rabbits.” The hunt is immediately called off, but Bugs isn’t about to ignore a setup like this. Before you know it, he’s moved in on the Fudd abode, taking full advantage of the bathroom facilities (including a suspect cel which has been frame-grabbed on several sites, possibly showing Bugs with more between his legs than just a bath towel), and demanding to be waited on for dinnaer. Elmer pulls a fast one, opening a door and inviting Bugs to “Step wight this way”. Bugs walks through, finding it is an exit to the porch, and has the door slammed behind him. Bugs pounds on the door, demanding to be let back in – then changes tactics, lapsing into a fake death scene reminiscent of the finale of “A Wild Hare”, claiming that he is dying of pneumonia from the night air. In the midst of his coughs and pathetic gasps for air, Bugs breaks the fourth wall, addressing the audience: “Hey, this scene ought to get me the Academy Award!” As Bugs gasps, “Say goodbye to Uncle Louie for me”, the door flies open, and Elmer realizes he is trapped by the rabbit’s game. Bugs is carried back in, and even rocked to sleep with a lullaby (in swing tempo) in Elmer’s arms. (Note this and other scenes for multiple backgrounds in which Freleng engages for possibly the first time in a game he and his crew would indulge in as a lark from time to time, to see just how much could be slipped past the censors without notice – the placement of various “art nudes” in frames on the wall, often in backgrounds that would linger for a considerable length of time on the screen. In some later productions, Freleng had to be slightly more subtle in pulling this off, choosing to place the paintings in backgrounds that rapidly panned across the screen, so that the images were only visible for a few frames at a time.) A telegram arrives at the front door. Uncle Louie has kicked the bucket – but an inventory of taxes has devoured the entire inheritance, and exceeded it, “Which leaves you owing us $1.98. PLEASE REMIT.” After a chase, Bugs is quickly ousted – followed by another messenger delivery. From an unknown sender comes a giant “Easter greetings” in the form a huge egg. The egg pops open, revealing contents of several dozen rabbits, slightly smaller than Bugs, who greet Elmer in a unison, “Eh, what’s up, doc?”, and proceed to hop all over the place, taking over Elmer’s home once again.

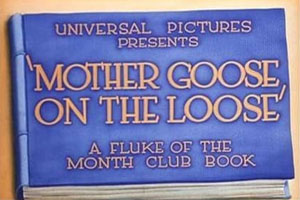

Mother Goose on the Loose (Lantz/Universal, 4/15/42 – Walter Lantz, dir.) – Lantz studios was far from above lifting the Tex Avery style of narrated one-shot for its own productions. A three-episode mini-series called “Crackpot Cruises” would begin it, mimicking the Avery travelogue spoofs such as “The Isle of Pingo Pongo.” Others would follow in Technicolor, including “Hysterical Highspots In American History”, and “Fair Today”, often featuring brief verbal interchanges between onscreen character and narrator. “Hysterical Highspots” even featured a moment in the credits where an animated army sergeant peers through an iris at the audience, calling for an inductee who hasn’t reported for military service by his draft number. But “Mother Goose” goes one step farther, lifting an Avery gag dating back to “Cinderella Meets Fella” in its finale. The film’s visuals are provided from the pages of a storybook, its cover proudly proclaiming it to be a choice of the “Fluke-Of-the Month Club’. Animator credits are displayed on page 2 in childlike scrawl, using childish nicknames for the personnel, including “Pictures drawed by ‘Muggsy’ Tipper”, “Story thunk up by ‘Buggsy’ Hardaway”, and “Music patter writ by ‘Boogie Woogie’ Calker”. The film is full of typical 40’s updates on old nursery rhymes (for example, Little Jack Horner pulling out a plum, splashing plum filling all over his face and hand, and remarking in Jerry Colonna impersonation, “Ah, yes. Messy things, aren’t they?”, and a girl who reacts to a kiss from Georgie Porgie with a Martha Raye yell of “Oh, Boy!”). And there’s plenty of shapely girls scattered about in every feminine role, to please the servicemen (though animation is rather rough around the edges compared to beauties who would appear in later productions such as “The Greatest Man in Siam”).

Mother Goose on the Loose (Lantz/Universal, 4/15/42 – Walter Lantz, dir.) – Lantz studios was far from above lifting the Tex Avery style of narrated one-shot for its own productions. A three-episode mini-series called “Crackpot Cruises” would begin it, mimicking the Avery travelogue spoofs such as “The Isle of Pingo Pongo.” Others would follow in Technicolor, including “Hysterical Highspots In American History”, and “Fair Today”, often featuring brief verbal interchanges between onscreen character and narrator. “Hysterical Highspots” even featured a moment in the credits where an animated army sergeant peers through an iris at the audience, calling for an inductee who hasn’t reported for military service by his draft number. But “Mother Goose” goes one step farther, lifting an Avery gag dating back to “Cinderella Meets Fella” in its finale. The film’s visuals are provided from the pages of a storybook, its cover proudly proclaiming it to be a choice of the “Fluke-Of-the Month Club’. Animator credits are displayed on page 2 in childlike scrawl, using childish nicknames for the personnel, including “Pictures drawed by ‘Muggsy’ Tipper”, “Story thunk up by ‘Buggsy’ Hardaway”, and “Music patter writ by ‘Boogie Woogie’ Calker”. The film is full of typical 40’s updates on old nursery rhymes (for example, Little Jack Horner pulling out a plum, splashing plum filling all over his face and hand, and remarking in Jerry Colonna impersonation, “Ah, yes. Messy things, aren’t they?”, and a girl who reacts to a kiss from Georgie Porgie with a Martha Raye yell of “Oh, Boy!”). And there’s plenty of shapely girls scattered about in every feminine role, to please the servicemen (though animation is rather rough around the edges compared to beauties who would appear in later productions such as “The Greatest Man in Siam”).

Best animation error is a closeup on Old King Cole, where someone can’t tell Cole’s hair from the furpiece providing the lapel of his royal robes, and thus draws animal spots in his hairdo for a cel or two. An extended “House That Jack Built” sequence is presented as if a slide show, with the slide projectionist getting the images totally confused (upside down, sideways, etc.), unable to keep up with the rapid-fire recitation of the narrator. But the running gag of the film is Simple Simon, seen fishing in a pail. The narrator informs him repeatedly that he can’t catch anything in a pail. “No? Oh”, responds Simon dimly, then keeps right on fishing anyway. On his third appearance in the film, Simon is seen in a view with the camera pulled back to reveal his image on a theater screen, with the stage and a portion of the theater seats and aisle visible in the foreground. The narrator gives Simon his final warning, but shuts up quick, when there is a tug on Simon’s line. Simon lifts his fishing pole to reveal a shapely mermaid. The maid poses provocatively, then dives back into the pail. Simon quickly follows, disappearing from view into the pail. The narrator (a vocal impersonation of Frank Morgan (“The Wizard of Oz”)) doesn’t want to miss out on this action, and calls out “Hey, Simple, wait for me.” The narrator’s shadow passes across the theater screen as he struggles his way across a row of seats, and he appears in the aisle (conventional animation rather than live-action overlay), climbing to the stage and diving into the pail on the screen – only to get stopped cold by the shallow depth of the pail, with only his head stuck in the water and unable to follow the others, while the book cover closes upon him for the ending.

Best animation error is a closeup on Old King Cole, where someone can’t tell Cole’s hair from the furpiece providing the lapel of his royal robes, and thus draws animal spots in his hairdo for a cel or two. An extended “House That Jack Built” sequence is presented as if a slide show, with the slide projectionist getting the images totally confused (upside down, sideways, etc.), unable to keep up with the rapid-fire recitation of the narrator. But the running gag of the film is Simple Simon, seen fishing in a pail. The narrator informs him repeatedly that he can’t catch anything in a pail. “No? Oh”, responds Simon dimly, then keeps right on fishing anyway. On his third appearance in the film, Simon is seen in a view with the camera pulled back to reveal his image on a theater screen, with the stage and a portion of the theater seats and aisle visible in the foreground. The narrator gives Simon his final warning, but shuts up quick, when there is a tug on Simon’s line. Simon lifts his fishing pole to reveal a shapely mermaid. The maid poses provocatively, then dives back into the pail. Simon quickly follows, disappearing from view into the pail. The narrator (a vocal impersonation of Frank Morgan (“The Wizard of Oz”)) doesn’t want to miss out on this action, and calls out “Hey, Simple, wait for me.” The narrator’s shadow passes across the theater screen as he struggles his way across a row of seats, and he appears in the aisle (conventional animation rather than live-action overlay), climbing to the stage and diving into the pail on the screen – only to get stopped cold by the shallow depth of the pail, with only his head stuck in the water and unable to follow the others, while the book cover closes upon him for the ending.

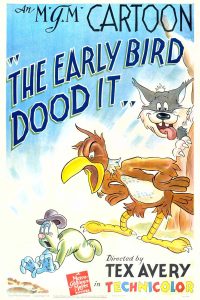

The Early Bird Dood It (MGM, 4/29/42 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Avery’s second film for MGM certainly was not the spectacular that “Blitz Wolf” aspired to be and achieved, but was perhaps more akin to one-shots at Warner such as “The Crackpot Quail.” It is basically a typical chase cartoon, requiring only three characters (and a one-scene walk-on by a mouse), but dressed up with fast-paced and surprising gags, and a few newly-minted ideas that would become Avery trademarks. There is the possibility that this subject matter was chosen as a beginning to Avery’s reactionism to the early “cute” style of Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising (whose names had not yet completely vanished from the credits of MGM cartoons), in that H-I had already produced a previous, more-or-less “straight” version of the early bird story, “The Early Bird and the Worm”. Avery himself had produced an essentially “cute” variant of the tale, “The Early Worm Gets the Bird” for Warner, but such version, taking a slant in casting its characters with Southern black dialect, bears virtually no resemblance to this MGM version. Instead, Avery frames a vicious triangle, as a derby-hatted worm (attempting an impression of Lou Costello) tries to double-cross a persistent early bird who wants him for breakfast, by befriending a stupid cat and convincing him to lie in wait for the bird the next morning.

The Early Bird Dood It (MGM, 4/29/42 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Avery’s second film for MGM certainly was not the spectacular that “Blitz Wolf” aspired to be and achieved, but was perhaps more akin to one-shots at Warner such as “The Crackpot Quail.” It is basically a typical chase cartoon, requiring only three characters (and a one-scene walk-on by a mouse), but dressed up with fast-paced and surprising gags, and a few newly-minted ideas that would become Avery trademarks. There is the possibility that this subject matter was chosen as a beginning to Avery’s reactionism to the early “cute” style of Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising (whose names had not yet completely vanished from the credits of MGM cartoons), in that H-I had already produced a previous, more-or-less “straight” version of the early bird story, “The Early Bird and the Worm”. Avery himself had produced an essentially “cute” variant of the tale, “The Early Worm Gets the Bird” for Warner, but such version, taking a slant in casting its characters with Southern black dialect, bears virtually no resemblance to this MGM version. Instead, Avery frames a vicious triangle, as a derby-hatted worm (attempting an impression of Lou Costello) tries to double-cross a persistent early bird who wants him for breakfast, by befriending a stupid cat and convincing him to lie in wait for the bird the next morning.

From the first shot of the film, an Avery standard gag is born. We pan across an early dawn landscape, with not a sound heard on the track, as the camera passes a sign, reading “Quiet, isn’t it?” Signs and lettering continue to play a role throughout the cartoon. The worm shows the cat a diagram of his master plan on a blueprint. Each of four illustrations takes special care to identify the position of the “Bird” by the printed word and a large white arrow. The final illustration shows the same word and arrow, not pointing to a picture of the bird, but to a bulge in the cat’s stomach, indicating the bird is inside. The worm transitions the scene by pulling upon a curtain ring, lowering a curtain over the shot with the words printed upon it, “Next Morning”. When the curtain rises, a large paw emerges from behind a tree, holding a sign reading “Cat”, and pointing to the feline behind the tree. The cat leaps out as the bird arrives, covering the bird’s eyes with his paws to ask “Guess who?” “Well, offhand, I’d say the cat” responds the bird without hesitation. The cat reacts with frustration at having his surprise spoiled, and accuses the bird of cheating and having peeked. The bird whacks the cat with a club, leading to another word gag, as the cat visibly mouths a barrage of angry words, while the soundtrack goes silent, and the words “Censored dialogue” appear superimposed upon the screen. But the most surprising sign gag is an off-the-wall self-promotion of the very cartoon we are presently watching. The bird and worm pass before a large roadside billboard, containing a movie ad for the feature “Mrs. Minimum” (spoof upon the MGM feature “Mrs. Miniver”), with a small image in the corner plugging the short subject playing with it – “The Early Bird Dood It”, with image duplicating the title card we have already seen. The characters pause to read the ad, and the bird remarks, “Hey. I hear that’s a pretty funny cartoon.” “Well, I hope it’s funnier than this one”, responds the worm. The cat and bird eventually plunge off a cliff, and the worm soulfully begins to play “Taps” on a small trumpet in memoriam of them – then switches the tune to a happy jazzy riff at their demise. (This identical gag was stolen by Famous studios a decade later for the Noveltoon, “The Oily Bird”.) The worm returns to his hole, happy at last to be rid of the bird. But no sooner does he descend into the hole, than the sound of loud swallowing is heard. From within the hole emerges the very-live early bird, wearing the worm’s derby, and emitting a Lou Costello whistle. The happy bird disappears behind a tree trunk – and we hear another loud swallow. Now, the head of the cat emerges from around the tree, wearing the derby, and repeating the Costello whistle. The cat ends the film by reaching behind the tree, and pulling out a sign to display to the audience – introducing another trademark Avery sign gag, reading “Sad ending, ain’t it?”

From the first shot of the film, an Avery standard gag is born. We pan across an early dawn landscape, with not a sound heard on the track, as the camera passes a sign, reading “Quiet, isn’t it?” Signs and lettering continue to play a role throughout the cartoon. The worm shows the cat a diagram of his master plan on a blueprint. Each of four illustrations takes special care to identify the position of the “Bird” by the printed word and a large white arrow. The final illustration shows the same word and arrow, not pointing to a picture of the bird, but to a bulge in the cat’s stomach, indicating the bird is inside. The worm transitions the scene by pulling upon a curtain ring, lowering a curtain over the shot with the words printed upon it, “Next Morning”. When the curtain rises, a large paw emerges from behind a tree, holding a sign reading “Cat”, and pointing to the feline behind the tree. The cat leaps out as the bird arrives, covering the bird’s eyes with his paws to ask “Guess who?” “Well, offhand, I’d say the cat” responds the bird without hesitation. The cat reacts with frustration at having his surprise spoiled, and accuses the bird of cheating and having peeked. The bird whacks the cat with a club, leading to another word gag, as the cat visibly mouths a barrage of angry words, while the soundtrack goes silent, and the words “Censored dialogue” appear superimposed upon the screen. But the most surprising sign gag is an off-the-wall self-promotion of the very cartoon we are presently watching. The bird and worm pass before a large roadside billboard, containing a movie ad for the feature “Mrs. Minimum” (spoof upon the MGM feature “Mrs. Miniver”), with a small image in the corner plugging the short subject playing with it – “The Early Bird Dood It”, with image duplicating the title card we have already seen. The characters pause to read the ad, and the bird remarks, “Hey. I hear that’s a pretty funny cartoon.” “Well, I hope it’s funnier than this one”, responds the worm. The cat and bird eventually plunge off a cliff, and the worm soulfully begins to play “Taps” on a small trumpet in memoriam of them – then switches the tune to a happy jazzy riff at their demise. (This identical gag was stolen by Famous studios a decade later for the Noveltoon, “The Oily Bird”.) The worm returns to his hole, happy at last to be rid of the bird. But no sooner does he descend into the hole, than the sound of loud swallowing is heard. From within the hole emerges the very-live early bird, wearing the worm’s derby, and emitting a Lou Costello whistle. The happy bird disappears behind a tree trunk – and we hear another loud swallow. Now, the head of the cat emerges from around the tree, wearing the derby, and repeating the Costello whistle. The cat ends the film by reaching behind the tree, and pulling out a sign to display to the audience – introducing another trademark Avery sign gag, reading “Sad ending, ain’t it?”

Tricky Business (Terrytoons/Fox, Gandy Goose), 5/1/42 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.) – Gandy astounds Sourpuss, with a box of 50 assorted magic tricks he has just picked up from a magic store. They range from cards that shuffle in aerial loops and defy gravity, to a magic hoop that transforms persons that go through it from one species to another (a gag ripped off from Disney’s 1937 “Magician Mickey”). Gandy takes the curious Sourpuss to the store by way of a disappearing and reappearing magic carpet. The store’s doorbell is a rigged booby trap, first squirting water in Sourpuss’s face, then hitting him with a boxing glove. Gandy gains entry unscathed, and, as a voice answers the question “Is anybody here?” with a resounding “No”, Gandy and Sourpuss have the place to themselves to look around. Wouldn’t you know it that one of the items for sale is a magic pencil – straight out of the previous picture of the same title. Gandy picks it up, using it to draw on the wall a drinking glass and a jug. The jug tips to fill the glass with an unknown brew, then disappears, leaving only the filled glass. “Here’s to your health”, says Gandy, downing the drink. Sourpuss wants his turn, and draws on another wall a beer tap, and a mug. He presses the tap handle, filling the mug with cold beer. “Here’s to your health”, Sourpuss repeats, and swigs down the drink. But the brew has a strange effect upon him, and quickly causes him to spit out a dozen rabbits. Sourpuss trues to rub out the rabbits with a rifle, but the rabbits retaliate, producing a dozen daggers out of a bulls-eye target, temporarily pinning Sourpuss to a wall. “Don’t touch anything”, warns a frustrated Sourpuss. But Gandy demonstrates a magic egg, placing it atop his head, pounding upon it, and having the orb disappear from his head, and roll out intact from his mouth. Sourpuss repeats the action on his own head, but merely squashes the egg all over his face. Gandy stuffs a cigar in Sourpuss’s lips, which promptly explodes – followed by another exploding cigar emerging from the cat’s mouth, and another, and another, on and on. The explosions produce little anthropomorphic flames, who hop into Sourpuss’s pants. Sourpuss extinguishes the blaze with water from a magic water pitcher, but can’t get the water flow from the pitcher to shut off. He hurls the pitcher at the wall, producing a flood from the hole made in the wall, which washes him and Gandy out of the store. The cat has taken all he can stand, and rants for Gandy to never mention magic or tricks to him again, or he will sue – while cards, rabbits, wands, and other assorted magic bric-a-brac fly from his coat and flailing sleeves.

Tricky Business (Terrytoons/Fox, Gandy Goose), 5/1/42 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.) – Gandy astounds Sourpuss, with a box of 50 assorted magic tricks he has just picked up from a magic store. They range from cards that shuffle in aerial loops and defy gravity, to a magic hoop that transforms persons that go through it from one species to another (a gag ripped off from Disney’s 1937 “Magician Mickey”). Gandy takes the curious Sourpuss to the store by way of a disappearing and reappearing magic carpet. The store’s doorbell is a rigged booby trap, first squirting water in Sourpuss’s face, then hitting him with a boxing glove. Gandy gains entry unscathed, and, as a voice answers the question “Is anybody here?” with a resounding “No”, Gandy and Sourpuss have the place to themselves to look around. Wouldn’t you know it that one of the items for sale is a magic pencil – straight out of the previous picture of the same title. Gandy picks it up, using it to draw on the wall a drinking glass and a jug. The jug tips to fill the glass with an unknown brew, then disappears, leaving only the filled glass. “Here’s to your health”, says Gandy, downing the drink. Sourpuss wants his turn, and draws on another wall a beer tap, and a mug. He presses the tap handle, filling the mug with cold beer. “Here’s to your health”, Sourpuss repeats, and swigs down the drink. But the brew has a strange effect upon him, and quickly causes him to spit out a dozen rabbits. Sourpuss trues to rub out the rabbits with a rifle, but the rabbits retaliate, producing a dozen daggers out of a bulls-eye target, temporarily pinning Sourpuss to a wall. “Don’t touch anything”, warns a frustrated Sourpuss. But Gandy demonstrates a magic egg, placing it atop his head, pounding upon it, and having the orb disappear from his head, and roll out intact from his mouth. Sourpuss repeats the action on his own head, but merely squashes the egg all over his face. Gandy stuffs a cigar in Sourpuss’s lips, which promptly explodes – followed by another exploding cigar emerging from the cat’s mouth, and another, and another, on and on. The explosions produce little anthropomorphic flames, who hop into Sourpuss’s pants. Sourpuss extinguishes the blaze with water from a magic water pitcher, but can’t get the water flow from the pitcher to shut off. He hurls the pitcher at the wall, producing a flood from the hole made in the wall, which washes him and Gandy out of the store. The cat has taken all he can stand, and rants for Gandy to never mention magic or tricks to him again, or he will sue – while cards, rabbits, wands, and other assorted magic bric-a-brac fly from his coat and flailing sleeves.

Hold the Lion, Please (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 6/6/42 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.). receives an honorable mention. Though not quite indicating the characters know they are in a cartoon, the film definitely ends with some first-person addressing of the audience by Bugs, and a visual prompt also intended to unmistakably cue in the audience on a character’s identity. For the most part, the film is another of Jones’s early slow-paced efforts, with very little plot. A lion is getting on in years, and is the subject of gossip among his jungle subjects, who believe he is nothing but a “has-been”, too weak and weak-minded to even catch prey such as a – rabbit? The king of beasts overhears, and insists that he can so catch a rabbit, so goes off looking for Bugs. There are few if any standout gags, until the very end, when the lion, about to do Bugs in, receives a telephone call from his wife, who insists that he come home right away, and drop what he is doing. The lion can’t get a word of protest in edgewise, and meekly apologizes to Bugs, “Sorry I can’t stay and kill ‘ya”, but suggests that maybe they can take it up again another time. As the henpecked lion exits the cartoon, Bugs reacts with disdain at the lion’s personal life, addressing the audience directly. “How do ya’ like that? The guy wants to be king of the jungle, and he ain’t even master in his own home. Now ain’t dat rich. Now me, I wear the pants in my family.” Suddenly, another rabbit appears behind him – a twin in appearance, but wearing a dress. The hand of some unknown stagehand holds out a sign behind the second rabbit’s head, reading “Mrs. Bugs Bunny”. “Eh, what’s up, doc, dear?”, she asks Bugs. Without a word, Bugs shuts up, and slinks into his rabbit hole. “Eh, who wears the pants in this family?”, says Mrs. Bugs, also addressing the audience, as she quickly raises the hemline of her dress, revealing a full pair of blue trousers worn underneath, for the iris out.

Hold the Lion, Please (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 6/6/42 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.). receives an honorable mention. Though not quite indicating the characters know they are in a cartoon, the film definitely ends with some first-person addressing of the audience by Bugs, and a visual prompt also intended to unmistakably cue in the audience on a character’s identity. For the most part, the film is another of Jones’s early slow-paced efforts, with very little plot. A lion is getting on in years, and is the subject of gossip among his jungle subjects, who believe he is nothing but a “has-been”, too weak and weak-minded to even catch prey such as a – rabbit? The king of beasts overhears, and insists that he can so catch a rabbit, so goes off looking for Bugs. There are few if any standout gags, until the very end, when the lion, about to do Bugs in, receives a telephone call from his wife, who insists that he come home right away, and drop what he is doing. The lion can’t get a word of protest in edgewise, and meekly apologizes to Bugs, “Sorry I can’t stay and kill ‘ya”, but suggests that maybe they can take it up again another time. As the henpecked lion exits the cartoon, Bugs reacts with disdain at the lion’s personal life, addressing the audience directly. “How do ya’ like that? The guy wants to be king of the jungle, and he ain’t even master in his own home. Now ain’t dat rich. Now me, I wear the pants in my family.” Suddenly, another rabbit appears behind him – a twin in appearance, but wearing a dress. The hand of some unknown stagehand holds out a sign behind the second rabbit’s head, reading “Mrs. Bugs Bunny”. “Eh, what’s up, doc, dear?”, she asks Bugs. Without a word, Bugs shuts up, and slinks into his rabbit hole. “Eh, who wears the pants in this family?”, says Mrs. Bugs, also addressing the audience, as she quickly raises the hemline of her dress, revealing a full pair of blue trousers worn underneath, for the iris out.

Bats In the Belfry (MGM, 7/4/42 – Jerry Brewer, dir.) – This entire cartoon addresses the audience in the first person, as three bats act as our tour guides through the world of their church belfry, and their “dippy in the dome” way of life. The camera pans up to a rafter, where the three bats hang by their feet, asleep. The camera pivots to turn the image of the bats right-side up. The largest of the three sleepily opens his eyes, notices us, and begins to say hello – then is taken suddenly aback in shock. “You’re upside down”, he nervously observes. He tilts his head at various angles, trying to understand what he is seeing, then looks “up” and “down” from his viewpoint to get an idea of his own position. His expression changes, and he chuckles sheepishly, “Shucks, I’m upside down”. He calls out into the darkness to the proprietor of our local theater, shouting “Turn the theater over”. With a creaking groan sounding like the bending of a wooden foundation, the camera once again pivots 180 degrees, placing the bats in upside-down position again. The large bat hops down from the rafter, then yanks off the rafter his two companions. “We got an audience”, he informs them. The two smaller bats retract backwards, clinging in terror to the sides of the large bat for protection. The large bat tears them away, and begins out tour, explaining that a belfry has for years and years been a bat’s traditional home, and the ringing of the bells is responsible for a bat’s reputation of being nuts, jangling their brains somewhat out of whack. The bats sing a song about themselves, musically itemizing all the kinds of bells that can have an effect on them – even a “Southern Belle” from whom they receive a phone call from a belfry down in Birmingham, Alabam. They quarrel over who has the right to claim the title of biggest bat, in the course of which their smallest member (Brickbat) is knocked off a rafter and falls. Yet suddenly, he reappears behind the others, unharmed. “Didn’t it hurt?” asks the large bat. With the sounds of loose marbles rattling around in his skull, Brickbat shakes his head no. “Do it to me”, requests the large bat, and the others gladly push him from the beam, resulting in the sound of terrific crashes below. The middle-size bat chews his fingernails off from nervousness at their deed, while Brickbat tosses a dustpan and broom to whoever may be below to sweep up the pieces. But the large bat returns, dazed and staggering, but conscious enough to give Brickbat a few good whacks on the head. The brief finale has the bats awaiting the chiming of twelve o’clock – the hour guaranteed to drive them insane. Unfortunately, the climax is a big disappointment, as it is lacking in punch and exceptionally brief, as the bats ride the clapper of one of the swinging bells, then race at the camera as the iris out closes upon Brickbat. As there was no real plot, they could have at least built up the payoff to make our eight-minute journey feel more worthwhile.

Bats In the Belfry (MGM, 7/4/42 – Jerry Brewer, dir.) – This entire cartoon addresses the audience in the first person, as three bats act as our tour guides through the world of their church belfry, and their “dippy in the dome” way of life. The camera pans up to a rafter, where the three bats hang by their feet, asleep. The camera pivots to turn the image of the bats right-side up. The largest of the three sleepily opens his eyes, notices us, and begins to say hello – then is taken suddenly aback in shock. “You’re upside down”, he nervously observes. He tilts his head at various angles, trying to understand what he is seeing, then looks “up” and “down” from his viewpoint to get an idea of his own position. His expression changes, and he chuckles sheepishly, “Shucks, I’m upside down”. He calls out into the darkness to the proprietor of our local theater, shouting “Turn the theater over”. With a creaking groan sounding like the bending of a wooden foundation, the camera once again pivots 180 degrees, placing the bats in upside-down position again. The large bat hops down from the rafter, then yanks off the rafter his two companions. “We got an audience”, he informs them. The two smaller bats retract backwards, clinging in terror to the sides of the large bat for protection. The large bat tears them away, and begins out tour, explaining that a belfry has for years and years been a bat’s traditional home, and the ringing of the bells is responsible for a bat’s reputation of being nuts, jangling their brains somewhat out of whack. The bats sing a song about themselves, musically itemizing all the kinds of bells that can have an effect on them – even a “Southern Belle” from whom they receive a phone call from a belfry down in Birmingham, Alabam. They quarrel over who has the right to claim the title of biggest bat, in the course of which their smallest member (Brickbat) is knocked off a rafter and falls. Yet suddenly, he reappears behind the others, unharmed. “Didn’t it hurt?” asks the large bat. With the sounds of loose marbles rattling around in his skull, Brickbat shakes his head no. “Do it to me”, requests the large bat, and the others gladly push him from the beam, resulting in the sound of terrific crashes below. The middle-size bat chews his fingernails off from nervousness at their deed, while Brickbat tosses a dustpan and broom to whoever may be below to sweep up the pieces. But the large bat returns, dazed and staggering, but conscious enough to give Brickbat a few good whacks on the head. The brief finale has the bats awaiting the chiming of twelve o’clock – the hour guaranteed to drive them insane. Unfortunately, the climax is a big disappointment, as it is lacking in punch and exceptionally brief, as the bats ride the clapper of one of the swinging bells, then race at the camera as the iris out closes upon Brickbat. As there was no real plot, they could have at least built up the payoff to make our eight-minute journey feel more worthwhile.

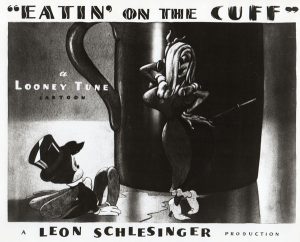

Eatin’ on the Cuff (or the Moth Who Came To Dinner) (Warner, Looney Tunes, 8/14/42 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Another Warner film shot partially in live-action with a silent camera, with human voice dubbed by Mel Blanc. A live pianist (Leo White) introduces a story about a moth engaged to a honeybee, the moth donning tuxedo in preparation for their impending wedding day. Unfortunately, on his way to the church, the moth is sidetracked by the irresistible attraction of a line of men standing at the bar in a local saloon, wearing long tasty trousers – with pre-war cuffs. In a matter of seconds, the zooming moth has reduced the entire row of men to their boxer shorts. The moth sits with full belly on a shelf, but has to spit out one of those aggravating zippers. He is spotted by a man-chasing Black Widow Spider, who talks like a cross between Marjorie Main and Brenda and Cobina from the Bob Hope radio show. She is ugly as a mud fence with a large protruding nose, but styles her hair like Veronica Lake (with her nose poking through) to attempt attractiveness. She soon discovers that it is easier to attract a moth with a flame, which she produces from a cigarette lighter. The moth is soon her virtual prisoner in her lair, being pursued wildly by her. But to the moth’s rescue arrives the honeybee, who’s been waiting at the church for her beau. She battles the spider in a fierce duel, winning with her secret weapon. As the widow proclaims, “Confidentially, she stings!” As the lovers embrace, the scene returns to the live-action pianist, who completes his song, but confides to the audience that he still can’t understand what the bee could possibly have seen in the silly moth. The moth himself appears, sitting upon a key of the piano keyboard, and remarks in anger “Oh, yeah?” The moth repeats his old trick, zipping around the pianist’s legs until he is reduced to stockings, garters, and plaid shorts. The pianist screams “Woo woo!”, and in super speed makes an exit off the stage and into the sound stage wings, knocking over furniture and props everywhere he goes.

Eatin’ on the Cuff (or the Moth Who Came To Dinner) (Warner, Looney Tunes, 8/14/42 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Another Warner film shot partially in live-action with a silent camera, with human voice dubbed by Mel Blanc. A live pianist (Leo White) introduces a story about a moth engaged to a honeybee, the moth donning tuxedo in preparation for their impending wedding day. Unfortunately, on his way to the church, the moth is sidetracked by the irresistible attraction of a line of men standing at the bar in a local saloon, wearing long tasty trousers – with pre-war cuffs. In a matter of seconds, the zooming moth has reduced the entire row of men to their boxer shorts. The moth sits with full belly on a shelf, but has to spit out one of those aggravating zippers. He is spotted by a man-chasing Black Widow Spider, who talks like a cross between Marjorie Main and Brenda and Cobina from the Bob Hope radio show. She is ugly as a mud fence with a large protruding nose, but styles her hair like Veronica Lake (with her nose poking through) to attempt attractiveness. She soon discovers that it is easier to attract a moth with a flame, which she produces from a cigarette lighter. The moth is soon her virtual prisoner in her lair, being pursued wildly by her. But to the moth’s rescue arrives the honeybee, who’s been waiting at the church for her beau. She battles the spider in a fierce duel, winning with her secret weapon. As the widow proclaims, “Confidentially, she stings!” As the lovers embrace, the scene returns to the live-action pianist, who completes his song, but confides to the audience that he still can’t understand what the bee could possibly have seen in the silly moth. The moth himself appears, sitting upon a key of the piano keyboard, and remarks in anger “Oh, yeah?” The moth repeats his old trick, zipping around the pianist’s legs until he is reduced to stockings, garters, and plaid shorts. The pianist screams “Woo woo!”, and in super speed makes an exit off the stage and into the sound stage wings, knocking over furniture and props everywhere he goes.

NEXT WEEK: Glory be – its ‘42 and ‘43!

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the MeTV cartoons channel adopted a program of cartoons that would last possibly for an hour or so that contained cartoons with similar themes, kind of a TV version of these posts on cartoon research. Actually passed combinations of posts in this area could act as influenced to the show each week. Another great lineup of cartoons here! I especially like the all too rare GANDY GOOSE AND SOURPUSS cartoon because it seems that in this series, there is more attention paid to the characters as cartoon characters. So they are very aware of themselves as drawings, and there’s a lot of characters morphing into different things! This cartoon is no exception, with the strangest image being sourpuss, spitting out little rabbits! I also appreciated the outline of the Avery cartoon from MGM. I remember seeing the “censored“ gag and really believing that the television station was censoring the cartoon. I remember wondering “what is that cat screaming?” Little did I know that this was part of the actual cartoon itself. Very funny stuff here. Always appreciate these posts.

“Let me have men about me that are fat,

Sleek-headed men, and such as sleep a-nights.” — Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene ii

“…They’re men. To them, something intellectually stimulating is comparing today’s Elmer Fudd with the original, fatter Fudd.” — Peggy Bundy, “Married… with Children

Julius Caesar would have loved the portly Elmer Fudd of “The Wabbit Who Came to Supper” — and it looks as if Bugs is really happy to see him, too! Either that, or maybe Bugs just caught a glimpse of the nude paintings on the wall, though the bottle of “Sissy Stuff” on the bathroom shelf is certainly suggestive.

I first saw “Mother Goose on the Loose” as a teenager and was keenly conscious of the protuberant nipples beneath the material of Mary’s and Little Bo Peep’s blouses. Not even Red at her raciest showed that much. As I watch the cartoon now, however, what I notice is how much Mary’s little lamb looks like Andy Panda.

Some of the rhyming verse in “Bats in the Belfry” recalls “The Bells” by Edgar Allan Poe, in which “the tintinnabulation that so musically wells” starts out pleasantly enough but ultimately descends into madness and despair.

In “Fleets of Stren’th”, as in other wartime Popeye cartoons made contemporaneously with the Superman series, notably “The Mighty Navy”, Popeye’s shipmates bear an uncanny resemblance to the Man of Steel. Maybe the artists just used the same model sheets. I guess scrap metal wasn’t the only thing being recycled for the war effort.