1943 continued to abound in self-conscious cartoons, ever aware of their theatrical venue, and eager to draw the audience into the storylines through direct reference. Characters also continue to comment upon their own medium and other companion media as well, and one of them even turns animator. It was no wonder that personalities of characters were becoming so entrenched into the consciousness of the average movie-goer, when you could almost believe that these ink and paint images shared their very thoughts and ideas with you as if they were best friends, and might just exit the screen to take a seat beside you to enjoy the show.

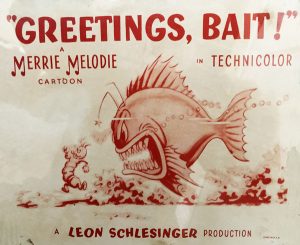

Greetings, Bait (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 5/15/43 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Friz Freleng seemed to hop through the late thirties and early forties from one worm picture to another, each progressing from the last. First was The Bookworm, produced during his stint at MGM, with a raven and a title character who, like a real worm, was armless and legless. Next, the direct sequel, The Bookworm Turns for MGM, where the bookworm acquired limbs to make his poses more human-like. When Friz returned to Warner Brothers, he brought along his raven, but was afraid to reuse the bookworm character, both since ownership rights might be claimed by MGM, and as Chuck Jones already had a bookworm character appearing in the Sniffles the Mouse series. Freleng thus reinvented the worm as a mustached tenor, singing and speaking in the style of Jerry Colonna, for The Wacky Worm. Finally, the title presently to be discussed was produced, dropping the raven, and allowing the Colonna worm to appear in a starring vehicle on his own. It would prove the last of Freleng’s worm cycle, but it would have the distinction of gleaning a nomination for an Academy Award.

Greetings, Bait (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 5/15/43 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Friz Freleng seemed to hop through the late thirties and early forties from one worm picture to another, each progressing from the last. First was The Bookworm, produced during his stint at MGM, with a raven and a title character who, like a real worm, was armless and legless. Next, the direct sequel, The Bookworm Turns for MGM, where the bookworm acquired limbs to make his poses more human-like. When Friz returned to Warner Brothers, he brought along his raven, but was afraid to reuse the bookworm character, both since ownership rights might be claimed by MGM, and as Chuck Jones already had a bookworm character appearing in the Sniffles the Mouse series. Freleng thus reinvented the worm as a mustached tenor, singing and speaking in the style of Jerry Colonna, for The Wacky Worm. Finally, the title presently to be discussed was produced, dropping the raven, and allowing the Colonna worm to appear in a starring vehicle on his own. It would prove the last of Freleng’s worm cycle, but it would have the distinction of gleaning a nomination for an Academy Award.

Today finds the Colonna worm engaged in a fishing excursion – as bait. However, the clever worm isn’t about to be speared on a hook to be offered to the piscatorial community as fish food. Instead, he is the avid “fisherman’s helper”, working in close cooperation with an unseen human fisherman on a lake in a boat. He descends into the water on a line rigged with a platter and cover similar to what one might see in a restaurant to bring food to the table. Below the surface, the worm engages in multiple “clever ruses” to acquire catches for his human master. He strings a series of neon signs to the line, advertising dinner at Joe’s below, then arranges two slices of beread and a lettuce leaf as a mattress on the plate to lay himself in, adding a sign on a toothpick reading “Today’s special”. When the fish tries to take a bite, the worm leaps out, and slaps the metal lid closed upon him. The worm tugs on the line to be returned to the surface (though pausing halfway in his ascent to substitute an even bigger fish under the lid), then deposits the catch into his master’s fish bag on board the boat. A goofy-looking fish is too dumb to take the bait, but is nevertheless caught when the worm poses as a circus acrobat, spinning on a spinner below the hook by gripping it with his teeth. He convinces the fish to try performing the same stunt, allowing the dummy to be quickly reeled in by his master.

A third fish is coaxed onto the plate by the worm disguising as a seductive mermaid. “Sea wolf” comments the worm as the love-crazed fish dives into the trap. The worm tugs to be pulled back to the boat, bit finds that the line is reeled in not by the fisherman, but by a crab leaning out from a nearby ledge, taking hold of the fishing line with its claws. To Freleng’s credit, the crab design does not follow that traditional to Disney and MGM since “Hawaiian Holiday”, but is a bug-eyed monster, with its eyes extending far from its shell on the ends of individual, independently-moving antennae. This leads to a great sight gag, as each eye antenna reaches around a submerged barrel, to spot the worm behind it from different directions. A split-screen shows us vision from the crab’s point of view, as the worm moves away from one eye and toward the other, facing the camera on one side of the screen, yet running from it on the other screen. The worm finally grabs both eye antennae, and knots them together, causing a severely twisted and distorted knotted-view in the eyes of the crab. The worm continues his attempts to escape, even resorting to impersonating a sea horse, until he gets fed up with the chasing. Confronting the crab, the worm challenges, “You wouldn’t be so brave, knave, if you didn’t have that shell to protect you.” The crab demonstrates his courage, opening hatch doors in his shell, and emerging in a bare, semi-skeletal form. “Puny, isn’t he?”, observes the worm to the audience. Before the battle begins, the worm offers an extended warning to the audience. “Ladies and gentlemen. The following scenes will be so brutal and horrifying, that for the benefit of those with faint hearts, weak stomachs, and 4F ratings, we will return you to the surface, while I reduce this upstart to crab meat.” The camera indeed returns to the lake surface, where the placid water is suddenly disturbed by violent shock waves from below. A tug at the line finally cues the fisherman to reel in the platter. As the metal lid is lifted, we see revealed not the crab, but the worm, heavily bandaged and lying on a stretcher. “I could be wrong, you know”, remarks the worm to the camera. The camera’s view pans upwards, finally revealing the full face of the fisherman – a caricature of none other than the real-life Jerry Colonna, who responds to the worm with a variant of his catch-phrase: “Ah, yes – Embarrassing, isn’t it?”

A third fish is coaxed onto the plate by the worm disguising as a seductive mermaid. “Sea wolf” comments the worm as the love-crazed fish dives into the trap. The worm tugs to be pulled back to the boat, bit finds that the line is reeled in not by the fisherman, but by a crab leaning out from a nearby ledge, taking hold of the fishing line with its claws. To Freleng’s credit, the crab design does not follow that traditional to Disney and MGM since “Hawaiian Holiday”, but is a bug-eyed monster, with its eyes extending far from its shell on the ends of individual, independently-moving antennae. This leads to a great sight gag, as each eye antenna reaches around a submerged barrel, to spot the worm behind it from different directions. A split-screen shows us vision from the crab’s point of view, as the worm moves away from one eye and toward the other, facing the camera on one side of the screen, yet running from it on the other screen. The worm finally grabs both eye antennae, and knots them together, causing a severely twisted and distorted knotted-view in the eyes of the crab. The worm continues his attempts to escape, even resorting to impersonating a sea horse, until he gets fed up with the chasing. Confronting the crab, the worm challenges, “You wouldn’t be so brave, knave, if you didn’t have that shell to protect you.” The crab demonstrates his courage, opening hatch doors in his shell, and emerging in a bare, semi-skeletal form. “Puny, isn’t he?”, observes the worm to the audience. Before the battle begins, the worm offers an extended warning to the audience. “Ladies and gentlemen. The following scenes will be so brutal and horrifying, that for the benefit of those with faint hearts, weak stomachs, and 4F ratings, we will return you to the surface, while I reduce this upstart to crab meat.” The camera indeed returns to the lake surface, where the placid water is suddenly disturbed by violent shock waves from below. A tug at the line finally cues the fisherman to reel in the platter. As the metal lid is lifted, we see revealed not the crab, but the worm, heavily bandaged and lying on a stretcher. “I could be wrong, you know”, remarks the worm to the camera. The camera’s view pans upwards, finally revealing the full face of the fisherman – a caricature of none other than the real-life Jerry Colonna, who responds to the worm with a variant of his catch-phrase: “Ah, yes – Embarrassing, isn’t it?”

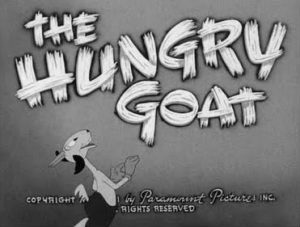

The Hungry Goat {Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 6/25/43 – Dan Gordon, dir.) – Popeye’s first year without Fleischer was a year of experimentation, with efforts both to break away from the standard love triangles and spinach themes, and to keep up with the increasong zaniness of rival studios. We’ve seen “Me Musical Nephews” as an example of such trends last week. Another primary example is this episode, in which the fourth wall is again broken clean through, and the entire story seems to unfold on two planes of existence at once. Learning in large doses from Avery, Famous borrows the concept of the opening titles gag from “Tortoise Beats Hare”, having its titular guest star, a talking goat named Billy the Kid, meander past the screen in front of the title card, and onto another background, while singing a lyric revision of the current pop hit, “Jingle Jangle Jingle”, referring to his favorite meal of tin cans in his tummy as doing the jangling. He suddenly stops, recollecting what was written on the title, and wonders if his eyes deceived him. He calls out in the direction of the theater projection booth, “Operator, will you run this picture back to the title, please?” The movement of the images slows and freezes, and we see the shadow of a projector shutter appear across part of the frame, then reverse in spinning direction, as the animation attains normal speed in reverse, and the sound is even played backwards. The goat returns to a position in front of the title card, reading it aloud. “How do you like that. I gotta be hungry, and me about to die from hunger now”, complains the goat. The cartoon finally commences, the goat roaming the streets in search of tin cans. He calls out to the theater crowd, “Is there a tomato can in the house?” Suddenly, a pot of gold appears, in the form of a stash of empty tin cans piled high on the sidewalk. The goat’s front tooth converts to the shape of a can opener in Swiss Army knife fashion, and he charges the pile. But the clamshell bucket of a crane grabs away the entire stack before the goat can dive into it, dumping the load into the bed of a truck labeled “Scrap metal drive”. Finding nothing more, and with wartime priorities in place, the goat finds himself at the docks. Seeing the situation as hopeless, he decides to “take a powder” and end it all. He braces himself, then charges to fling himself off one of the piers into the ocean. His plan is thwarted when he collides headfirst into the side of a battleship docked near the wharf. The goat moans that a guy can’t even commit suicide these days – but his eyes bug out as he views the ship in a different light. From his POV, the ship looks like a floating equivalent of giant tin cans. Food at last!

The Hungry Goat {Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 6/25/43 – Dan Gordon, dir.) – Popeye’s first year without Fleischer was a year of experimentation, with efforts both to break away from the standard love triangles and spinach themes, and to keep up with the increasong zaniness of rival studios. We’ve seen “Me Musical Nephews” as an example of such trends last week. Another primary example is this episode, in which the fourth wall is again broken clean through, and the entire story seems to unfold on two planes of existence at once. Learning in large doses from Avery, Famous borrows the concept of the opening titles gag from “Tortoise Beats Hare”, having its titular guest star, a talking goat named Billy the Kid, meander past the screen in front of the title card, and onto another background, while singing a lyric revision of the current pop hit, “Jingle Jangle Jingle”, referring to his favorite meal of tin cans in his tummy as doing the jangling. He suddenly stops, recollecting what was written on the title, and wonders if his eyes deceived him. He calls out in the direction of the theater projection booth, “Operator, will you run this picture back to the title, please?” The movement of the images slows and freezes, and we see the shadow of a projector shutter appear across part of the frame, then reverse in spinning direction, as the animation attains normal speed in reverse, and the sound is even played backwards. The goat returns to a position in front of the title card, reading it aloud. “How do you like that. I gotta be hungry, and me about to die from hunger now”, complains the goat. The cartoon finally commences, the goat roaming the streets in search of tin cans. He calls out to the theater crowd, “Is there a tomato can in the house?” Suddenly, a pot of gold appears, in the form of a stash of empty tin cans piled high on the sidewalk. The goat’s front tooth converts to the shape of a can opener in Swiss Army knife fashion, and he charges the pile. But the clamshell bucket of a crane grabs away the entire stack before the goat can dive into it, dumping the load into the bed of a truck labeled “Scrap metal drive”. Finding nothing more, and with wartime priorities in place, the goat finds himself at the docks. Seeing the situation as hopeless, he decides to “take a powder” and end it all. He braces himself, then charges to fling himself off one of the piers into the ocean. His plan is thwarted when he collides headfirst into the side of a battleship docked near the wharf. The goat moans that a guy can’t even commit suicide these days – but his eyes bug out as he views the ship in a different light. From his POV, the ship looks like a floating equivalent of giant tin cans. Food at last!

Of course, among the crew is Popeye, who doesn’t take kindly to the goat making a first tasty tidbit out of the bucket he is using to swab the decks. The goat rigs a booby-trapped hatch for Popeye to fall into, followed by the dropping upon his head of about ten cannonballs. Popeye’s arms emerge from a ventilation funnel, armed with a large mallet – but he is aimed above the wrong target, and almost smashes the Admiral of the fleet over the head. Billy provides the Admiral with warning of the danger, so that Popeye does not face court marshall. Instead, the Admiral befriends Billy, and orders Popeye not to let harm befall him. Meanwhile, the Admiral announces he is going to the movies, asserting the powers of his rank over Popeye by uttering a childish “Nyah” in his face. The Admiral calls for a taxi (which instantly appears on deck – great service from these drivers), and is off to the show. Popeye resumes his chase of the goat, but the goat halts him with a word of caution. “You know what the Admiral said. He said he was goin’ to the movies. For all you know, he may be out there watching us right now.” How true, as the shadow of the Admiral passes in front of the theater screen at out local movie house, and he takes a seat. “There he is now”, observes the goat from the screen. “Hiya, Admiral!”, calls the goat. Popeye stands at attention and salutes, and the Admiral’s shadow rises from his seat, to return the salute. From here, the goat has the edge on Popeye, who is hesitant to take his full vengeance out upon the goat in front of the Admiral. The goat runs Popeye ragged, smacking him with the hook from the ship’s crane, knocking him overboard, then setting him aloft, hooked to the wheel of the ship’s catapult plane. To ensure the progress of his eating objectives, the goat slips a large projection slide onto the screen, reading, “Calling Admiral Kurry in a hurry to the phone in the lobby.” The Admiral’s shadow again rises to hastily take the call. Then the goat reveals to the audience what he is doing – munching holes in the hull, downing small cannons wrapped in steel plates like a hot dog on a bun, and smacking on the barrels of the larger artillery pieces until they look like Swiss cheese. When the Admiral returns to his seat, a kid in the next seat alerts him to the real picture by his laughter, “He’s eatin’ the boat.” The Admiral reacts in a panicked frenzy, and excuses himself from the crowd, hastily departing across the row of seats. Soon, the taxi is driving up the gangplank as the Admiral returns on deck. He orders Popeye to come down, and Popeye finally gets loose from the plane, landing on deck standing at attention. “Where is that goat?”, demands the Admiral. Hilarious laughter is heard from within the theater, as Popeye and the Admiral turn to look out at the audience. The goat has taken the Admiral’s seat, and laughs himself silly in the foreground at the frustrated sailors, as their image fades from the screen, and the Paramount mountain fades in – still with the goat laughing just ahead of us in the foreground seats.

Of course, among the crew is Popeye, who doesn’t take kindly to the goat making a first tasty tidbit out of the bucket he is using to swab the decks. The goat rigs a booby-trapped hatch for Popeye to fall into, followed by the dropping upon his head of about ten cannonballs. Popeye’s arms emerge from a ventilation funnel, armed with a large mallet – but he is aimed above the wrong target, and almost smashes the Admiral of the fleet over the head. Billy provides the Admiral with warning of the danger, so that Popeye does not face court marshall. Instead, the Admiral befriends Billy, and orders Popeye not to let harm befall him. Meanwhile, the Admiral announces he is going to the movies, asserting the powers of his rank over Popeye by uttering a childish “Nyah” in his face. The Admiral calls for a taxi (which instantly appears on deck – great service from these drivers), and is off to the show. Popeye resumes his chase of the goat, but the goat halts him with a word of caution. “You know what the Admiral said. He said he was goin’ to the movies. For all you know, he may be out there watching us right now.” How true, as the shadow of the Admiral passes in front of the theater screen at out local movie house, and he takes a seat. “There he is now”, observes the goat from the screen. “Hiya, Admiral!”, calls the goat. Popeye stands at attention and salutes, and the Admiral’s shadow rises from his seat, to return the salute. From here, the goat has the edge on Popeye, who is hesitant to take his full vengeance out upon the goat in front of the Admiral. The goat runs Popeye ragged, smacking him with the hook from the ship’s crane, knocking him overboard, then setting him aloft, hooked to the wheel of the ship’s catapult plane. To ensure the progress of his eating objectives, the goat slips a large projection slide onto the screen, reading, “Calling Admiral Kurry in a hurry to the phone in the lobby.” The Admiral’s shadow again rises to hastily take the call. Then the goat reveals to the audience what he is doing – munching holes in the hull, downing small cannons wrapped in steel plates like a hot dog on a bun, and smacking on the barrels of the larger artillery pieces until they look like Swiss cheese. When the Admiral returns to his seat, a kid in the next seat alerts him to the real picture by his laughter, “He’s eatin’ the boat.” The Admiral reacts in a panicked frenzy, and excuses himself from the crowd, hastily departing across the row of seats. Soon, the taxi is driving up the gangplank as the Admiral returns on deck. He orders Popeye to come down, and Popeye finally gets loose from the plane, landing on deck standing at attention. “Where is that goat?”, demands the Admiral. Hilarious laughter is heard from within the theater, as Popeye and the Admiral turn to look out at the audience. The goat has taken the Admiral’s seat, and laughs himself silly in the foreground at the frustrated sailors, as their image fades from the screen, and the Paramount mountain fades in – still with the goat laughing just ahead of us in the foreground seats.

Porky Pig’s Feat (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky and Daffy), 7/17/43 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – Porky and Daffy’s last appearance in black and white – and one of their best. A substantial hotel bill faces our heroes at the Broken Arms Hotel, where the manager waits for payment. Porky informs him that “My partner, Daffy Duck, is out c-c-cashing a check.” But the money from such instrument is not lasting long, as Daffy is rolling for the works in a crap game with the hotel’s elevator operator. Daffy’s last roll is described by the Rochester-like voice of the operator. “Oh Oh. Snake eyes. Too bad. You is a dead duck, duck.” Typical madness ensues as Daffy and Porky attempt to escape the hotel without paying, but are ever-thwarted by the determined manager. The film is full of unusual signature camera angles, Tashlin-style. Daffy and Porky scamper down a corridor in low-angle perspective, carrying a tower of their luggage, to an elevator door at the far end of the corridor. Then the camera zooms to the elevator, watching the floor indicator mark its floor-by-floor descent – only to spring back to our floor within a split second, knocking gears and springs out of the mechanism, as the door opens and the camera tracks backwards up the corridor to Porky’s room, our heroes being marched back to starting point by the manager right behind them. A recurring gag has the manager sent falling down a seemingly-endless spiral staircase, seen bouncing from one stair to another in vertical perspective looking down at him circling within circles. An extreme close-up on Daffy’s and Porky’s eyes reflects the manager bouncing in his fall, from one iris of the boys to the next and the next. A perspective swing on a rope to the next building only results in a reverse swing picking up the manager as an additional passenger, and a nailing-up of the window by him upon their return to the hotel room.

Porky Pig’s Feat (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky and Daffy), 7/17/43 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – Porky and Daffy’s last appearance in black and white – and one of their best. A substantial hotel bill faces our heroes at the Broken Arms Hotel, where the manager waits for payment. Porky informs him that “My partner, Daffy Duck, is out c-c-cashing a check.” But the money from such instrument is not lasting long, as Daffy is rolling for the works in a crap game with the hotel’s elevator operator. Daffy’s last roll is described by the Rochester-like voice of the operator. “Oh Oh. Snake eyes. Too bad. You is a dead duck, duck.” Typical madness ensues as Daffy and Porky attempt to escape the hotel without paying, but are ever-thwarted by the determined manager. The film is full of unusual signature camera angles, Tashlin-style. Daffy and Porky scamper down a corridor in low-angle perspective, carrying a tower of their luggage, to an elevator door at the far end of the corridor. Then the camera zooms to the elevator, watching the floor indicator mark its floor-by-floor descent – only to spring back to our floor within a split second, knocking gears and springs out of the mechanism, as the door opens and the camera tracks backwards up the corridor to Porky’s room, our heroes being marched back to starting point by the manager right behind them. A recurring gag has the manager sent falling down a seemingly-endless spiral staircase, seen bouncing from one stair to another in vertical perspective looking down at him circling within circles. An extreme close-up on Daffy’s and Porky’s eyes reflects the manager bouncing in his fall, from one iris of the boys to the next and the next. A perspective swing on a rope to the next building only results in a reverse swing picking up the manager as an additional passenger, and a nailing-up of the window by him upon their return to the hotel room.

The scene changes to winter, the boys now held prisoner in the hotel room until they pay up. Porky and Daffy wear balls and chains upon their ankles. Porky remarks, “Gosh, if Bugs Bunny was only here.” “Yeah, Bugs Bunny, my hero. He can get out of any spot”, observes Daffy Porky recalls seeing Bugs outwit a hunter in a Leon Schlesinger cartoon. Daffy races to a wall telephone, to call up the wabbit for advice. The voice of Bugs answers on the other end of the line. Daffy informs him of the “palooka manager” who has them locked up, and asks how to get out. Bugs asks, “Did you try the elevator? Throw him down the stairs? Swing across on a rope?” “We tried all those ways”, responds Daffy. A door to the next hotel room swings open, to reveal inside none other than Bugs (in one of his few appearances in black and white), talking on a second wall phone, with a ball and chain around his ankle. Looking through the doorway at Daffy and Porky, Bugs remarks in somewhat Jerry Colonna-style, “Ah, don’t work, do they?”

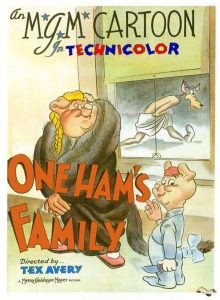

One Ham’s Family (MGM. 8/14/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – An Avery-style sequel to the Three Little Pigs, with a holiday theme. The big bad wolf as usual can’t blow the brick house down, but vows he will find a way in – if it takes until Christmas. Christmas finally comes, but with some changes in Practical Pig’s life, as the mailbox changes to “Mr. and Mrs.”, and an additional smaller mailbox sprouts reading “Jr.”. Pinto Colvig, reprising the voice of Practical, tells Junior (fashioned as a personification of Red Skelton’s “mean widdle kid” character from radio) all about Santa Claus. When mom and pop are asleep, Junior (after making sure they are sleeping soundly by testing them with the sounds of shotgun fire) heads downstairs to intercept Santa at the fireplace. The wolf, peering through a window, gets the idea, and quickly dons a Santa suit, entering the home through an elevator conveniently installed in the chimney, and luring Junior into a sack for his present. But Junior is not fooled at all, and is already out of the sack as the wolf reaches the front door, bidding him, “Good night, mister wolf”. The wolf doesn’t catch on until already outside, then examines the contents of his sack, finding inside a giant lollipop, on which appears the word “Sucker”. Regaining entry to the home, a merry chase is on, leaving destruction in its wake. Avery paraphrases a signature dialogue line from “Tortoise Beats Hare” – “I bang and bash him like this all through the picture.” Junior appears at the front door, disguised as a messenger delivering a telegram to the wolf. The message reads, “Don’t look now, but your tail is on fire. Love, Jr. P.S. Sucker!!” Sure enough, the message is right. The wolf scrambles to the sink to fill a bucket of water, but before he can sit in it, Junior substitutes a bucket of gasoline. BOOM!! The wolf disappears from sight through a hole in the roof. Turning to the camera, Junior observes, “Well, I cannot heckle the wolf any more ‘till he gets back. I might as well heckle you people out there.” Junior pulls into the shot a blackboard, on the shelf of which rests a large stick of chalk. He uses the chalk to produce ear-piercing scrapes as he drags it across the chalkboard, then closes the thought with “Oh, I sure is a mean little kid, ain’t I?” The final sequence has Avery lifting from Freleng’s “Greetings, Bait”, as the wolf and Junior disappear into a darkened room, the wolf wielding an axe. Before the camera can follow, Junior appears at the doorway, holding a flagman’s “STOP” sign. “Don’t come in here. This will be entirely too brutal to witness. Keep your distance. Get back!” The camera pulls back, as Junior is yanked into the room by the wolf’s hand, and the sounds of a raging battle are heard inside. The clatter awakens mom and dad, who hurry downstairs, only to find Junior calmly waiting in the doorway of the semi-wrecked room, wishing his parents “Merry Christmas”. “Junior, you’ve got a whipping coming to you”, says Momma Pig. “And you’ve got a present coming to you”, says Junior, presenting Mom with a large box. She opens it to find “A fur coat”. But a fur suspiciously recognizable, including a tail still heavily bandaged from the previous fire. “This is just what I need”, remarks Mama, modeling the fur. “You and me both, sister”, bellows the voice of the wolf, reduced to underwear and a towel, grabbing away the fur, and hustling out the front door, which closes to reveal a sign posted on its interior side: “Corny ending, isn’t it?”

One Ham’s Family (MGM. 8/14/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – An Avery-style sequel to the Three Little Pigs, with a holiday theme. The big bad wolf as usual can’t blow the brick house down, but vows he will find a way in – if it takes until Christmas. Christmas finally comes, but with some changes in Practical Pig’s life, as the mailbox changes to “Mr. and Mrs.”, and an additional smaller mailbox sprouts reading “Jr.”. Pinto Colvig, reprising the voice of Practical, tells Junior (fashioned as a personification of Red Skelton’s “mean widdle kid” character from radio) all about Santa Claus. When mom and pop are asleep, Junior (after making sure they are sleeping soundly by testing them with the sounds of shotgun fire) heads downstairs to intercept Santa at the fireplace. The wolf, peering through a window, gets the idea, and quickly dons a Santa suit, entering the home through an elevator conveniently installed in the chimney, and luring Junior into a sack for his present. But Junior is not fooled at all, and is already out of the sack as the wolf reaches the front door, bidding him, “Good night, mister wolf”. The wolf doesn’t catch on until already outside, then examines the contents of his sack, finding inside a giant lollipop, on which appears the word “Sucker”. Regaining entry to the home, a merry chase is on, leaving destruction in its wake. Avery paraphrases a signature dialogue line from “Tortoise Beats Hare” – “I bang and bash him like this all through the picture.” Junior appears at the front door, disguised as a messenger delivering a telegram to the wolf. The message reads, “Don’t look now, but your tail is on fire. Love, Jr. P.S. Sucker!!” Sure enough, the message is right. The wolf scrambles to the sink to fill a bucket of water, but before he can sit in it, Junior substitutes a bucket of gasoline. BOOM!! The wolf disappears from sight through a hole in the roof. Turning to the camera, Junior observes, “Well, I cannot heckle the wolf any more ‘till he gets back. I might as well heckle you people out there.” Junior pulls into the shot a blackboard, on the shelf of which rests a large stick of chalk. He uses the chalk to produce ear-piercing scrapes as he drags it across the chalkboard, then closes the thought with “Oh, I sure is a mean little kid, ain’t I?” The final sequence has Avery lifting from Freleng’s “Greetings, Bait”, as the wolf and Junior disappear into a darkened room, the wolf wielding an axe. Before the camera can follow, Junior appears at the doorway, holding a flagman’s “STOP” sign. “Don’t come in here. This will be entirely too brutal to witness. Keep your distance. Get back!” The camera pulls back, as Junior is yanked into the room by the wolf’s hand, and the sounds of a raging battle are heard inside. The clatter awakens mom and dad, who hurry downstairs, only to find Junior calmly waiting in the doorway of the semi-wrecked room, wishing his parents “Merry Christmas”. “Junior, you’ve got a whipping coming to you”, says Momma Pig. “And you’ve got a present coming to you”, says Junior, presenting Mom with a large box. She opens it to find “A fur coat”. But a fur suspiciously recognizable, including a tail still heavily bandaged from the previous fire. “This is just what I need”, remarks Mama, modeling the fur. “You and me both, sister”, bellows the voice of the wolf, reduced to underwear and a towel, grabbing away the fur, and hustling out the front door, which closes to reveal a sign posted on its interior side: “Corny ending, isn’t it?”

Cartoons Ain’t Human (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 9/3/43 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Another Famous Studios experiment, and the last black and white title produced by the studio. This one directly harkens back to “Mutt and Jeff on Strike”, with a dash of influence from “Porky’s Preview”, being the first cartoon in quite some time about the task of actual animation. Popeye has taken up the hobby of cartooning for home movies, following a checklist of supplies needed: drawing board, pencils, erasers, pen and ink, tacks, and TONS OF PAPER. Popeye settles in at his animation desk, holds his hand poised to begin his first drawing, but stops – realizing you can’t make a picture without an idea. Looking around at objects in his studio, he spies a wall calendar depicting the stage act of Dipsy Glee Hotcha (likely intended to suggest burlesque queen Gypsy Rose Lee). Popeye brightens, spurs his pencil into action, and produces a drawing which he lifts from the board to admire, we the audience only seeing the blank side of the sheet from our view. A live hand enters the frame, carrying a rubber stamp, with which the hand inks onto the back of Popeye’s drawing, “Censored”. Popeye puts down his masterpiece, then finally gets an idea that’ll keep it clean, and whips out an ever-growing stack of drawings in nothing flat.

Cartoons Ain’t Human (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 9/3/43 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Another Famous Studios experiment, and the last black and white title produced by the studio. This one directly harkens back to “Mutt and Jeff on Strike”, with a dash of influence from “Porky’s Preview”, being the first cartoon in quite some time about the task of actual animation. Popeye has taken up the hobby of cartooning for home movies, following a checklist of supplies needed: drawing board, pencils, erasers, pen and ink, tacks, and TONS OF PAPER. Popeye settles in at his animation desk, holds his hand poised to begin his first drawing, but stops – realizing you can’t make a picture without an idea. Looking around at objects in his studio, he spies a wall calendar depicting the stage act of Dipsy Glee Hotcha (likely intended to suggest burlesque queen Gypsy Rose Lee). Popeye brightens, spurs his pencil into action, and produces a drawing which he lifts from the board to admire, we the audience only seeing the blank side of the sheet from our view. A live hand enters the frame, carrying a rubber stamp, with which the hand inks onto the back of Popeye’s drawing, “Censored”. Popeye puts down his masterpiece, then finally gets an idea that’ll keep it clean, and whips out an ever-growing stack of drawings in nothing flat.

The scene changes to an evening in Popeye’s home, where Olive and Popeye’s nephews attend the premiere of the sailor’s masterpiece. Popeye acts both as projectionist and one-man-band and sound-effects department, providing live underscore for the home movie film, apparently shot silent. The film is, as in Mutt and Jeff’s creation, a melodrama, entitled “Wages of Sin (less 20%)”. Popeye and Olive appear as its stars, but drawn with slightly exaggerated heads, torsos that resemble a flexible stick of chewing gum, and stick-figure arms and legs (except for Popeye’s forearms, which remain bulging). Backgrounds are bare outlines against solid gray. Popeye engages in some cheats, having a rooster crow by playing shadow-puppets with his hands in front of the projection lens. Olive, a poor farm lass, weeps as Popeye leaves the farm to seek his fortune. But Popeye is too shy – or is it chicken – to kiss Olive goodbye, viewing her puckered lips as transforming her face into that of a fish. Enter the villain and his equally sinister horse. They react to the nephews’ hisses and boos by hissing right back at them from the screen, quieting the nephews to silence, as halos appear above their heads. “Marry me and I shall tear up this mortgage”, says the villain to Olive, unrolling a document he thinks is the mortgage, but which is actually a “Burlesk” poster, the semi-clad woman thereon uttering a scream and hiding herself. (Popeye just couldn’t get away from the original idea from the wall calendar.) The villain drags Olive away by the hair, but Olive, long before cell phones, somehow has a phone wire connection to telephone Popeye, who is working for Newt’s Zoot Suits carrying a sandwich-sign board down the street, to come a-running to save her. Olive’s usual screams take an underplayed moment, as in the middle of her call for distress, she calmly takes time-out to powder her nose with a make-up kit. Popeye uses an array of transportation modes to reach the scene of Olive’s plight, including a taxi, a rowboat, riding a turtle bareback, a jeep, and inside the pouch of a kangaroo. Olive meanwhile evades bloodhounds in Little Eva style, wearing large ice blocks strapped to her ankles to ford a river, while the bloodhounds pursue by paddleboat. Finally, the villain resorts to the old wheeze of tying Olive to the railroad tracks. “Blood-curdling, isn’t it?” he remarks to the home audience. As the train approaches (lifting a gag straight out of “Porky’s Preview”, where the train rises and falls on a hill-and-dale track – and keeps rising and falling even when the track runs out), Popeye begins to gain on it, now riding a bull, which intersects the train in a tunnel, with only Popeye emerging after the train passes, to hang a sign on the tunnel reading “Fresh Hamburgers” (Where is Wimpy when you eed him?) One of Popeye’s nephews gets so excited with the action, he swings one hand in the air wildly, and flicks a switch on the movie projector, doubling its projection speed. The projector vibrates forward at the increased tempo, then dangles from its cord just off the projection table edge, so that the vibrations cause the film images to flash everywhere around the room. Olive and the kids hustle out of their seats, trying to keep up with the moving images to see how the picture ends. They climb walls, hang from the chandelier upside down, and even take a turn gazing out the window at the moon, when the projector aims its images to flash off the moon’s surface. In the end, the projector focuses its images in a close-up on Olive’s nose, where we see the animated Popeye reach the tracks, eat his spinach, transform into a rotating wheel of clam-digger shovels, and carve a tunnel under the few feet of track to which Olive is tied, letting the train pass them harmlessly, as the animated Popeye and Olive kiss, and a small curtain is pulled over their embrace, reading “The End.”

The scene changes to an evening in Popeye’s home, where Olive and Popeye’s nephews attend the premiere of the sailor’s masterpiece. Popeye acts both as projectionist and one-man-band and sound-effects department, providing live underscore for the home movie film, apparently shot silent. The film is, as in Mutt and Jeff’s creation, a melodrama, entitled “Wages of Sin (less 20%)”. Popeye and Olive appear as its stars, but drawn with slightly exaggerated heads, torsos that resemble a flexible stick of chewing gum, and stick-figure arms and legs (except for Popeye’s forearms, which remain bulging). Backgrounds are bare outlines against solid gray. Popeye engages in some cheats, having a rooster crow by playing shadow-puppets with his hands in front of the projection lens. Olive, a poor farm lass, weeps as Popeye leaves the farm to seek his fortune. But Popeye is too shy – or is it chicken – to kiss Olive goodbye, viewing her puckered lips as transforming her face into that of a fish. Enter the villain and his equally sinister horse. They react to the nephews’ hisses and boos by hissing right back at them from the screen, quieting the nephews to silence, as halos appear above their heads. “Marry me and I shall tear up this mortgage”, says the villain to Olive, unrolling a document he thinks is the mortgage, but which is actually a “Burlesk” poster, the semi-clad woman thereon uttering a scream and hiding herself. (Popeye just couldn’t get away from the original idea from the wall calendar.) The villain drags Olive away by the hair, but Olive, long before cell phones, somehow has a phone wire connection to telephone Popeye, who is working for Newt’s Zoot Suits carrying a sandwich-sign board down the street, to come a-running to save her. Olive’s usual screams take an underplayed moment, as in the middle of her call for distress, she calmly takes time-out to powder her nose with a make-up kit. Popeye uses an array of transportation modes to reach the scene of Olive’s plight, including a taxi, a rowboat, riding a turtle bareback, a jeep, and inside the pouch of a kangaroo. Olive meanwhile evades bloodhounds in Little Eva style, wearing large ice blocks strapped to her ankles to ford a river, while the bloodhounds pursue by paddleboat. Finally, the villain resorts to the old wheeze of tying Olive to the railroad tracks. “Blood-curdling, isn’t it?” he remarks to the home audience. As the train approaches (lifting a gag straight out of “Porky’s Preview”, where the train rises and falls on a hill-and-dale track – and keeps rising and falling even when the track runs out), Popeye begins to gain on it, now riding a bull, which intersects the train in a tunnel, with only Popeye emerging after the train passes, to hang a sign on the tunnel reading “Fresh Hamburgers” (Where is Wimpy when you eed him?) One of Popeye’s nephews gets so excited with the action, he swings one hand in the air wildly, and flicks a switch on the movie projector, doubling its projection speed. The projector vibrates forward at the increased tempo, then dangles from its cord just off the projection table edge, so that the vibrations cause the film images to flash everywhere around the room. Olive and the kids hustle out of their seats, trying to keep up with the moving images to see how the picture ends. They climb walls, hang from the chandelier upside down, and even take a turn gazing out the window at the moon, when the projector aims its images to flash off the moon’s surface. In the end, the projector focuses its images in a close-up on Olive’s nose, where we see the animated Popeye reach the tracks, eat his spinach, transform into a rotating wheel of clam-digger shovels, and carve a tunnel under the few feet of track to which Olive is tied, letting the train pass them harmlessly, as the animated Popeye and Olive kiss, and a small curtain is pulled over their embrace, reading “The End.”

Falling Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 10/23/43 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Bugs is more audience-conscious than usual in this one, beginning the film on the airstrip at a top secret military installation (where everything on the signboard intended to identify the field is censored – especially “What Men Think of Top Sergeant”). Bugs’ rabbit hole happens to be just underneath one of the large bombers being prepared for a run, where Bugs lounges atop an aerial bomb, reading a copy of the book “Victory Through Hare Power” (another jab by Clampett at the Disney legacy, Walt’s feature film having premiered only months before). Bugs begins chuckling, then belly-laughing, as he turns the book’s pages to us, remarking, “Get a load of this, folks.” He displays a page depicting a constant menace to aviation – the Gremlin, who destroys planes with diabolical sabotage. “Oh, mur-derr! Little men”, guffaws Bugs – until a sharp vibration below him startles him out of his humorous mood. The impacts he feels are from the large hammer of a miniature little man-like creature, whose head-coloring resembles a pilot’s helmet, protruding ears resemble wings, and tail is in the shape of a plane’s rudder and elevators. Bugs asks what’s all the hubbub, bub? “These blockbuster bombs don’t go off unless you hit them just right”, responds the little creature. Helpful Bugs responds, “Let me take a whack at it.” Handing the little man his carrot, Bugs takes up the hammer, and spins back to give the warhead a solid blow. A fraction of an inch before impact, Bugs’ hands stop in their tracks. “WHAT AM I DOING??”, shrieks Bugs. He turns to give the little man a piece of his mind, but only finds his carrot hovering in mid-air, the man disappeared. “Gasp”, utters Bugs. Addressing the audience again, Bugs inquires. “Do you suppose that coulda been – – a gremlin?” The little man reappears from behind Bugs’s head, screaming at the top of his lungs into Bugs’s ear, “IT AIN’T WENDELL WILKIE!!”

Falling Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 10/23/43 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Bugs is more audience-conscious than usual in this one, beginning the film on the airstrip at a top secret military installation (where everything on the signboard intended to identify the field is censored – especially “What Men Think of Top Sergeant”). Bugs’ rabbit hole happens to be just underneath one of the large bombers being prepared for a run, where Bugs lounges atop an aerial bomb, reading a copy of the book “Victory Through Hare Power” (another jab by Clampett at the Disney legacy, Walt’s feature film having premiered only months before). Bugs begins chuckling, then belly-laughing, as he turns the book’s pages to us, remarking, “Get a load of this, folks.” He displays a page depicting a constant menace to aviation – the Gremlin, who destroys planes with diabolical sabotage. “Oh, mur-derr! Little men”, guffaws Bugs – until a sharp vibration below him startles him out of his humorous mood. The impacts he feels are from the large hammer of a miniature little man-like creature, whose head-coloring resembles a pilot’s helmet, protruding ears resemble wings, and tail is in the shape of a plane’s rudder and elevators. Bugs asks what’s all the hubbub, bub? “These blockbuster bombs don’t go off unless you hit them just right”, responds the little creature. Helpful Bugs responds, “Let me take a whack at it.” Handing the little man his carrot, Bugs takes up the hammer, and spins back to give the warhead a solid blow. A fraction of an inch before impact, Bugs’ hands stop in their tracks. “WHAT AM I DOING??”, shrieks Bugs. He turns to give the little man a piece of his mind, but only finds his carrot hovering in mid-air, the man disappeared. “Gasp”, utters Bugs. Addressing the audience again, Bugs inquires. “Do you suppose that coulda been – – a gremlin?” The little man reappears from behind Bugs’s head, screaming at the top of his lungs into Bugs’s ear, “IT AIN’T WENDELL WILKIE!!”

Eventually, the gremlin lures Bugs into the bomber above them, spins the props, gives the tires a push, and gets the plane aloft, with the gremlin at the controls. Bugs has some harrowing scrapes where he repeatedly faces falling out of the plane, with a trail of banana peels left in his path leading to the side door, bomb bay doors opened under him, etc. One great gag has Bugs clinging to the outside of the door of the plane, his heart beating so hard, it protrudes from his chest fur, bearing the numbers of the army classification, “4F”. Bugs finally takes the controls of the plane, turning the vehicle sideways to narrowly slip between two buildings in its path. The plane rises to a dizzying height, then turns 180 degrees into a steep nose-dive. Clampett rivals Avery’s endless fall in “The Heckling Hare”, as the wings of the plane snap off, leaving the bomber falling helplessly through space. The gremlin is calmly nonchalant about his work, standing in the frame of one of the cabin windows, biding his time by playing with a yo-yo. Bugs meanwhile withers to a gelatinous form, sliding in a faint off of the pilot’s seat, as flat as a pancake. The numbers of the air speed readout on the instrument panel spiral wildly, ever upwards, then stop spinning entirely, displaying a new readout, in the words “Incredible, ain’t it?”. Just as the ground looms up for impending doom, a sputter is heard from the engines. (Interesting, as all the motors already broke off with the wings.) A few belches of black smoke puffs, and the plane comes to a complete stop in mid-air, only a few feet above the ground. Again addressing the audience person-to-person, both the gremlin and Buhs offer explanation. “Sorry, folks. We ran oitta gas”, says the gremlin. “Yeah”, adds Bugs, pointing to a gas rationing insignia now visible on the outer frame of the cockpit, “You know how it is with these “A” cards.”

Eventually, the gremlin lures Bugs into the bomber above them, spins the props, gives the tires a push, and gets the plane aloft, with the gremlin at the controls. Bugs has some harrowing scrapes where he repeatedly faces falling out of the plane, with a trail of banana peels left in his path leading to the side door, bomb bay doors opened under him, etc. One great gag has Bugs clinging to the outside of the door of the plane, his heart beating so hard, it protrudes from his chest fur, bearing the numbers of the army classification, “4F”. Bugs finally takes the controls of the plane, turning the vehicle sideways to narrowly slip between two buildings in its path. The plane rises to a dizzying height, then turns 180 degrees into a steep nose-dive. Clampett rivals Avery’s endless fall in “The Heckling Hare”, as the wings of the plane snap off, leaving the bomber falling helplessly through space. The gremlin is calmly nonchalant about his work, standing in the frame of one of the cabin windows, biding his time by playing with a yo-yo. Bugs meanwhile withers to a gelatinous form, sliding in a faint off of the pilot’s seat, as flat as a pancake. The numbers of the air speed readout on the instrument panel spiral wildly, ever upwards, then stop spinning entirely, displaying a new readout, in the words “Incredible, ain’t it?”. Just as the ground looms up for impending doom, a sputter is heard from the engines. (Interesting, as all the motors already broke off with the wings.) A few belches of black smoke puffs, and the plane comes to a complete stop in mid-air, only a few feet above the ground. Again addressing the audience person-to-person, both the gremlin and Buhs offer explanation. “Sorry, folks. We ran oitta gas”, says the gremlin. “Yeah”, adds Bugs, pointing to a gas rationing insignia now visible on the outer frame of the cockpit, “You know how it is with these “A” cards.”

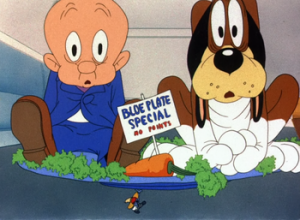

An Itch in Time (Warner, Elmer Fudd, 11/20/43 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – A Clampett classic qualifies for discussion by reason of Elmer Fudd self-promotionally spending the day reading Looney Tunes comics, with prominent images of Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig on the cover. The real story, however, centers upon the war of nerves between Elmer’s pet dog, and one A. Flea, a visiting hillbilly hobo seeking out new territory for a home – and a square meal. One observation is first in order before the story – the casting of Elmer in the plot. Elmer had not seen a starring role except with the “wabbit” for several years at this time. His role in the film would have seemed quite natural, and a likely choice on the original storyboard, for Porky Pig. (In fact, Porky and Elmer roles would be proven to be rather interchangeable years later by Friz Freleng, when a Porky vehicle, “Notes To You”, was remade in color with Elmer instead as Back Alley Oproar.) So why was Elmer chosen for the final film? Hard to say. One thought might be that the script was so good, Clampett may have wanted to ensure it would appear in color, while Porky was more closely associated with black-and-white. But Porky by this time had already been making crossovers into color films for about a year, so there’s no real reason why Clampett couldn’t as easily have produced a color Porky. Maybe Clampett was just getting tired of the pig in general. But then, thus didn’t stop him from featuring Porky in subsequent films like Baby Bottleneck and Kitty Kornered. So, your guess is as good as mine. It is further of note that this would mark Clampett’s first depiction of Elmer in a slimmed-down streamlined form, as opposed to his own “super-fat” model, unlike any of the model-sheets of his other fellow directors, which he had used since Wabbit Twouble. The slimmer depiction almost emphasizes the dimensional similarity with Porky, making one feel the pig could have easily been drawn into any of the poses which finally appeared on the screen.

An Itch in Time (Warner, Elmer Fudd, 11/20/43 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – A Clampett classic qualifies for discussion by reason of Elmer Fudd self-promotionally spending the day reading Looney Tunes comics, with prominent images of Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig on the cover. The real story, however, centers upon the war of nerves between Elmer’s pet dog, and one A. Flea, a visiting hillbilly hobo seeking out new territory for a home – and a square meal. One observation is first in order before the story – the casting of Elmer in the plot. Elmer had not seen a starring role except with the “wabbit” for several years at this time. His role in the film would have seemed quite natural, and a likely choice on the original storyboard, for Porky Pig. (In fact, Porky and Elmer roles would be proven to be rather interchangeable years later by Friz Freleng, when a Porky vehicle, “Notes To You”, was remade in color with Elmer instead as Back Alley Oproar.) So why was Elmer chosen for the final film? Hard to say. One thought might be that the script was so good, Clampett may have wanted to ensure it would appear in color, while Porky was more closely associated with black-and-white. But Porky by this time had already been making crossovers into color films for about a year, so there’s no real reason why Clampett couldn’t as easily have produced a color Porky. Maybe Clampett was just getting tired of the pig in general. But then, thus didn’t stop him from featuring Porky in subsequent films like Baby Bottleneck and Kitty Kornered. So, your guess is as good as mine. It is further of note that this would mark Clampett’s first depiction of Elmer in a slimmed-down streamlined form, as opposed to his own “super-fat” model, unlike any of the model-sheets of his other fellow directors, which he had used since Wabbit Twouble. The slimmer depiction almost emphasizes the dimensional similarity with Porky, making one feel the pig could have easily been drawn into any of the poses which finally appeared on the screen.

Clampett introduces A. Flea hopping through the plush carpet of Elmer’s home as a small dot, carrying a bindle stick. Much as Tex Avery had introduced an electric eel with someone holding up a sign in front of the camera for explanation in “Porky’s Duck Hunt”, Clampett repeats the business, with a hand-held sign appearing before the camera, reading “It’s a flea, folks”, followed by a second sign, reading “Teeny, ain’t he?” In a close-up, we finally see things from flea POV, as the flea pulls from his bindle stick a telescope far too large to fit inside, and surveys the terrain. A close shot is revealed on Elmer’s dog’s sizeable rear. “T-BONE!”, yells the flea in celebration, then begins the catchy ditty that permeates the entire score of the film, “There’ll Be Food Around the Corner For Me”. He hops upon the dog by bouncing off his rubbery nose, but quickly puts him back to sleep by singing a lullaby in his ear. Settling in to the dog’s fur, the flea tests the lay of the “land” by feeling for a tender spot, then slapping mustard, ketchup, and two slices of bread around it, and chowing down. The dog howls in pain, and responds with a little toothwork of his own, pursuing the flea through his own fur. The flea pauses, to hold up another tender patch of the dog’s own skin in the path of the pursuing teeth, allowing the dog to inflict another bite upon himself. The dog leaps into Elmer’s arms, whimpering. Elmer produces a can of flea powder, sprinkling it liberally over the dog’s person. It has no effect, as A. Flea uses the white stuff to perform ice-skating moves amidst the dog’s fur. Elmer issues the ultimate threat – one more scratch from the dog, and it’s bathtime. The dog envisions this as the world’s worst fate, and promises to be good, a halo appearing around his head. But the flea is relentless, bringing out armloads of heavy excavating equipment, chalking out a dotted line on the dog’s skin like a meat-cutter’s chart, and labeling the encircled area “Rump Roast”, then attacking the skin with pick axe, drill, and jack-hammer. The dog tries every means to resist his scratching instinct – even resorting to assaulting the family cat, just so the feline will respond with an attack of defensive scratching. But when A. Flea employs TNT, disappearing for safety into a door in one of the dog’s strands of fur marked “Hair Raid Shelter”, the fireworks display that erupts from the dog’s rear is more than he can stand. Elmer is finally aroused from his comics when the dog darts madly around the living room, dragging his flaming rear across the carpet (only to pause for a dialogue line Clampett tossed in for fun to test the censors: “Hey, I better cut this out. I may get to like it.”). Elmer drags the whimpering dog toward the bath bucket, but stops cold, realizing A. Flea has now changed targets, hopping on him. As Elmer kicks and scratches, the happy dog decides Elmer needs a bath. He thus carries Elmer bodily toward the bath tub. Unfortunately, the dog slips on a soap bar, depositing both characters into the suds. They come out with lather coatings that make them resemble Santa Claus and a reindeer – but just as suddenly are lifted out of the water, on a large platter. A. Flea carries the dish with both of them upon it, Elmer and the dog now surrounded by vegetable garnishments, and a sign on the platter reading “Blue Plate Special”, as the flea changes his lyric to “There’ll Be No More Meatless Tuesdays.” A commonplace Clampett gag, often excised by television censors, closes the film, as the cat views the scene in shock, remarks, “Well, now I’ve seen everything”, and with no thrills left to live for, pulls out a revolver, and blows his brains out.

Clampett introduces A. Flea hopping through the plush carpet of Elmer’s home as a small dot, carrying a bindle stick. Much as Tex Avery had introduced an electric eel with someone holding up a sign in front of the camera for explanation in “Porky’s Duck Hunt”, Clampett repeats the business, with a hand-held sign appearing before the camera, reading “It’s a flea, folks”, followed by a second sign, reading “Teeny, ain’t he?” In a close-up, we finally see things from flea POV, as the flea pulls from his bindle stick a telescope far too large to fit inside, and surveys the terrain. A close shot is revealed on Elmer’s dog’s sizeable rear. “T-BONE!”, yells the flea in celebration, then begins the catchy ditty that permeates the entire score of the film, “There’ll Be Food Around the Corner For Me”. He hops upon the dog by bouncing off his rubbery nose, but quickly puts him back to sleep by singing a lullaby in his ear. Settling in to the dog’s fur, the flea tests the lay of the “land” by feeling for a tender spot, then slapping mustard, ketchup, and two slices of bread around it, and chowing down. The dog howls in pain, and responds with a little toothwork of his own, pursuing the flea through his own fur. The flea pauses, to hold up another tender patch of the dog’s own skin in the path of the pursuing teeth, allowing the dog to inflict another bite upon himself. The dog leaps into Elmer’s arms, whimpering. Elmer produces a can of flea powder, sprinkling it liberally over the dog’s person. It has no effect, as A. Flea uses the white stuff to perform ice-skating moves amidst the dog’s fur. Elmer issues the ultimate threat – one more scratch from the dog, and it’s bathtime. The dog envisions this as the world’s worst fate, and promises to be good, a halo appearing around his head. But the flea is relentless, bringing out armloads of heavy excavating equipment, chalking out a dotted line on the dog’s skin like a meat-cutter’s chart, and labeling the encircled area “Rump Roast”, then attacking the skin with pick axe, drill, and jack-hammer. The dog tries every means to resist his scratching instinct – even resorting to assaulting the family cat, just so the feline will respond with an attack of defensive scratching. But when A. Flea employs TNT, disappearing for safety into a door in one of the dog’s strands of fur marked “Hair Raid Shelter”, the fireworks display that erupts from the dog’s rear is more than he can stand. Elmer is finally aroused from his comics when the dog darts madly around the living room, dragging his flaming rear across the carpet (only to pause for a dialogue line Clampett tossed in for fun to test the censors: “Hey, I better cut this out. I may get to like it.”). Elmer drags the whimpering dog toward the bath bucket, but stops cold, realizing A. Flea has now changed targets, hopping on him. As Elmer kicks and scratches, the happy dog decides Elmer needs a bath. He thus carries Elmer bodily toward the bath tub. Unfortunately, the dog slips on a soap bar, depositing both characters into the suds. They come out with lather coatings that make them resemble Santa Claus and a reindeer – but just as suddenly are lifted out of the water, on a large platter. A. Flea carries the dish with both of them upon it, Elmer and the dog now surrounded by vegetable garnishments, and a sign on the platter reading “Blue Plate Special”, as the flea changes his lyric to “There’ll Be No More Meatless Tuesdays.” A commonplace Clampett gag, often excised by television censors, closes the film, as the cat views the scene in shock, remarks, “Well, now I’ve seen everything”, and with no thrills left to live for, pulls out a revolver, and blows his brains out.

Way Down Yonder in the Corn (Screen Gems/Columbia, Fox and Crow, 11/25/43 – Bob Wickersham, dir.) – Displaying some simple but stylistic backgrounds foretelling some of the later work of UPA, this installment of the Fox and Crow series exhibits not only awareness of audience, but consciousness of being performers for our benefit. In a theme somewhat appropriate for the Halloween season, Farmer Fox shares with the audience, in the same manner as Bugs Bunny, his reading material from a volume entitled “How to Fox Crows”. The page turned to us informs that “Crows are allergic to scarecrows.” The camera pans up to Crow’s treehouse, where Crow also addresses us directly. “That’s right. They give me the creeps.” Fox immediately posts a sign on his property, advertising “Scarecrow wanted.” Crow hopes none will answer the ad, but then decides to take his own measures to ensure such result. Darting into his closet, Crow rummages among old Halloween costumes, retrieving a witch’s hat, a black robe, and a red fright wig. He covers his eyes as he approaches a mirror while wearing the material, then almost jumps to the ceiling at viewing his own image. Crow applies for the ad, leaping upon a pole and making an ugly face. Fox removes the sign, having found his man – but then the bickering begins about wages. Crow begins to walk out at Fox’s first offer, making panicky Fox bid against himself to ultimately increase the wage to 25 cents per hour plus overtime. Calling Crow a highway robber at his pay demands, Fox leaves Crow in charge of the crops, disappearing for a few moments into his foxhole apartment underground. As soon as Fox disappears, Crow helps himself to feasting on the entire field, saving for dessert the Fox’s favorite – a vine of luscious grapes. The elevator to Fox’s hole begins to rise, leaving Crow no time to devour the grapes, which he instead stuffs under his hat. Fox is horrified to find nearly all his crops gone, and zips back into the hole to retrieve an axe to swing at the scarecrow. Crow stands his ground, telling Fox to watch who he swings axes at. “Help’s gettin’ scarce. Where ya gonna get another scarecrow these days?” And besides, adds Crow, displaying the grapes, “Look what I saved for ya.” Fax is pacified at still retaining his beautiful grapes, but insulted Crow threatens to walk out again. Fox suggests they talk things over – over lunch. “Lunch?” – the magic word for Crow. Crow disappears down the foxhole elevator first, and by the time Fox can follow, Crow has raided the pantry, devouring everything in sight, but still demanding something for dessert. The grapes seem to be the only thing left, and Fox cautiously hides them behind his back. Fox eyes a steel safe with a combination lock, and mutters to himself, “He can’t have them” He creeps over to the safe, kneeling to twirl the dial to the combination. But Crow is on to him, and just as silently creeps up behind Fox, swapping for the grapes a lit stick of TNT. Fox places the dynamite stick in the safe, then Crow kicks him into the safe as well, slamming the door behind him. Crow enjoys his dessert, then settles down to sleep in Fox’s bed, as the dynamite fuse grows shorter and shorter, for a loud KABOOM that shakes the entire apartment.

Way Down Yonder in the Corn (Screen Gems/Columbia, Fox and Crow, 11/25/43 – Bob Wickersham, dir.) – Displaying some simple but stylistic backgrounds foretelling some of the later work of UPA, this installment of the Fox and Crow series exhibits not only awareness of audience, but consciousness of being performers for our benefit. In a theme somewhat appropriate for the Halloween season, Farmer Fox shares with the audience, in the same manner as Bugs Bunny, his reading material from a volume entitled “How to Fox Crows”. The page turned to us informs that “Crows are allergic to scarecrows.” The camera pans up to Crow’s treehouse, where Crow also addresses us directly. “That’s right. They give me the creeps.” Fox immediately posts a sign on his property, advertising “Scarecrow wanted.” Crow hopes none will answer the ad, but then decides to take his own measures to ensure such result. Darting into his closet, Crow rummages among old Halloween costumes, retrieving a witch’s hat, a black robe, and a red fright wig. He covers his eyes as he approaches a mirror while wearing the material, then almost jumps to the ceiling at viewing his own image. Crow applies for the ad, leaping upon a pole and making an ugly face. Fox removes the sign, having found his man – but then the bickering begins about wages. Crow begins to walk out at Fox’s first offer, making panicky Fox bid against himself to ultimately increase the wage to 25 cents per hour plus overtime. Calling Crow a highway robber at his pay demands, Fox leaves Crow in charge of the crops, disappearing for a few moments into his foxhole apartment underground. As soon as Fox disappears, Crow helps himself to feasting on the entire field, saving for dessert the Fox’s favorite – a vine of luscious grapes. The elevator to Fox’s hole begins to rise, leaving Crow no time to devour the grapes, which he instead stuffs under his hat. Fox is horrified to find nearly all his crops gone, and zips back into the hole to retrieve an axe to swing at the scarecrow. Crow stands his ground, telling Fox to watch who he swings axes at. “Help’s gettin’ scarce. Where ya gonna get another scarecrow these days?” And besides, adds Crow, displaying the grapes, “Look what I saved for ya.” Fax is pacified at still retaining his beautiful grapes, but insulted Crow threatens to walk out again. Fox suggests they talk things over – over lunch. “Lunch?” – the magic word for Crow. Crow disappears down the foxhole elevator first, and by the time Fox can follow, Crow has raided the pantry, devouring everything in sight, but still demanding something for dessert. The grapes seem to be the only thing left, and Fox cautiously hides them behind his back. Fox eyes a steel safe with a combination lock, and mutters to himself, “He can’t have them” He creeps over to the safe, kneeling to twirl the dial to the combination. But Crow is on to him, and just as silently creeps up behind Fox, swapping for the grapes a lit stick of TNT. Fox places the dynamite stick in the safe, then Crow kicks him into the safe as well, slamming the door behind him. Crow enjoys his dessert, then settles down to sleep in Fox’s bed, as the dynamite fuse grows shorter and shorter, for a loud KABOOM that shakes the entire apartment.

After a fade in, we visit the Fox abode on another day. Fox lies laid up in traction, while Crow still controls the bedroom. Somehow, in the cartoon world, word spreads fast of comic mishaps, and a radio broadcast gives an account of a local farmer whose scarecrow has raided his food and stolen his bed – and who is really the crow all the time. “What?”, screams Fox, leaping from his bandages in instant cure, grabbing up a shotgun. The savvy radio announcer also seems aware that Fox is listening to the very broadcast, and suggests, “Killing is too good for him. Why don’t you scare him to death?” So, Fox dresses up in a costume identical to Crow’s , dubbing himself “Sidney Scarecrow”, and enters the bedroom, carrying the axe. Crow’s willies kick in, and no amount of explaining seems likely to pacify the intruder anxious to rid the world of the imposter. Crow runs to the property end of Fox’s underground tunnels, and, having no more paths to follow, makes his own, by tunneling madly. Fox follows in hot pursuit, and a lengthy trek through various climates and terrain is chronicled by means of above-ground panning shots following the digging sounds below, punctuated by periodic pops up to the surface by our two stars, who each dive back into their holes upon spotting each other, for more digging. When they run out of land, they bob through the ocean like porpoises, Crow commenting, “Sidney, this is ridiculous.” Finally, they reach an amusement park, and pop up in the darkness of the Tunnel of Love of a massive roller coaster. Fox reaches out as the car emerges into daylight, about to place a stranglehold on Crow. But Crow transforms himself out of character, into his professional mode, observing the situation for what it really is. “This picture is just about over. Let’s stop this bickering and quarreling. I really like you. You’re a good straight man. Let’s be friends. Let’s make up.” Fox finally extends his hand in friendship, just as the roller coaster car reaches a near-vertical drop. In a neat perspective shot, the car plunges down the track, heading straight at the camera lens, and our stars crash through it, shattering the screen image into shards, and revealing behind it the Columbia logo for the ending.

NEXT WEEK: Still More for ‘43 and ‘44.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Ah, “The Hungry Goat”. When we first embarked upon this Animation Trail, that was the first cartoon that popped into my head. What a scream! It really stood out from all the other Popeye cartoons I first encountered in the television syndication package years ago, and not just because Popeye only has three lines in it, two of them “Aye aye, sir!” With “The Hungry Goat”, Famous not only kept up with the screwball zaniness of the rival studios, it surpassed them by leaps and bounds. The wildest thing about it is that here’s a wartime cartoon, a genre that’s supposed to boost morale on the home front, and the title character makes monkeys out of our men in uniform and sabotages the war effort, yet he totally gets away with it! It ends with Billy the Kid laughing it up with the audience in the movie theatre, having reduced Popeye and the admiral to the status of a Dimwit or a Meathead. As violations of the Production Code go, this goes way beyond any risqué pictures of burlesque dancers that Popeye might have drawn. But the cartoon’s extreme self-consciousness probably went a long way to mitigate its more subversive elements. After all, “it’s only a cartoon.”

Unfortunately Billy the Kid didn’t survive the studio’s relocation back to New York, and “The Hungry Goat” remains his one and only film appearance. But maybe some of Billy’s anarchic spirit lives on in Blackie — though as catchphrases go, Billy’s “I’m normal, ain’t I?” is hands down better than Blackie’s “Are you kiddin’?”

A greetings-gated, Colonna-saturated post this week, isn’t it? My mother liked a lot of radio comedians like Jerry Colonna, Joe Penner and Eddie Cantor when she was young, and she was able to identify them for me when they were caricatured in old cartoons. But when she tried to explain what exactly made them funny, I just didn’t get it. What’s funny about asking someone if they want to buy a duck? Then again, I’d probably run into the same wall if I tried to tell a young person why Steve Martin was such a popular stand-up back in the day that he sold out stadiums. “He was hilarious! He was a wild and crazy guy who put tuna fish sandwiches in his armpits, said “Excuse me,” and sang a song about King Tut!” “Oh, Grandpa….”

I’ve always thought the crews behind Cartoons Ain’t Human and Porky’s Preview kinda whizzed on their own joke by providing professional smooth animation to the supposedly crude stick-figure characters in the films-within-the-films. The premise should have been pushed to the hilt and featured jerky, stilted movement to accentuate the amateurishness and ineptitude of our heroes’ homemade productions. Not only would this have been truer to both cartoon’s concept, I believe it would have made them even funnier. Maybe producers feared audiences weren’t sophisticated enough to “get it”, and would feel cheated. At any rate, Porky and Popeye are apparently truly talented animators.

When the camera pans across the garden to show how Crow has devoured it all, we see the stripped-bare bones of a cow (and see them again on the return trip). Is it just me, or would that have been pushing it?

Dan Gordon left Famous Studios shortly after the Paramount takeover. Other than that fact, I don’t know much about him. Makes me wonder whether if he had stayed, Paramount cartoons would not have descended into mediocrity. “The Hungry Goat” contains several innovations: Besides what is mentioned in the article, there is a sequence of stills alternating between Popeye and the goat.

It is a popular misconception that goats eat tin cans. They are browsers and like to sample food before they eat it. They enjoy the labels and the glue on tin cans, and will lick them clean, but won’t eat the metal.

An Itch in Time and Porky Pig’s Feat are two of my favorites, while I hate Greetings, Bait. Rare I can say that about a Freleng!