Tis’ almost St. Patrick’s Day – the time of year when it is said everyone becomes Irish. The day that leads good men to consume great quantities of food-colored beer, or dream of turning green swimming in the waters of the Chicago River. While cartoons have abounded in various forms of Irish expression – including a plethora of heavily-brogued policemen in traditional stereotype fashion – the most lasting animated imagery for the season has to be the sight of those little wee men who never moved off the gold standard – the leprechauns! With a tip o’ me hat, I present the first in a series of articles paying tribute to these diminutive mischief makers.

While elves, dwarfs, and pixies found periodic recurring roles in early animation, not so for the leprechaun. One has to wonder why. Despite the Irish being neither an uncommon nor unpopular immigrant population in depictions either on stage or in film in Western culture, was the mythos surrounding the leprechaun originally viewed as too ethnic or inaccessible to the average viewer? True, it is unlikely that a rank and file moviegoer of the bygone days would have instantly recognized what a banshee was (considering that Disney had to build up considerable explanation for the concept even in 1959‘s Darby O’Gill and the Little People). But as popular culture today stands, it seems almost hard to conceptualize a world where a leprechaun may have been an unknown commodity. Still, animation, traditionally happy in depicting fanciful and mythical creatures, seems to have kept its distance from the subject until considerably late in the game.

An unknown entry is 1930’s “Irish Stew” from the newly formed Terrytoons studio, which was not included in the CBS distribution package and for which no plot description is as yet known. Anyone with information on this film is encouraged to contribute.

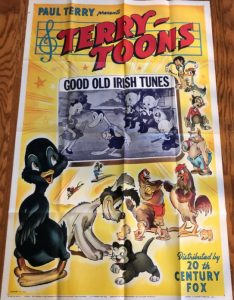

Still, whether said early Terrytoon was the first or no, the Terry studio does appear to get the credit for what may be animation’s first foray with leprechauns – at least debatably. The original version of the film, however, was another title excluded from the CBS television manifest – this time assumably because it was too identical in content to a Technicolor remake. Thus we fast-forward to Songs of Erin (Terryroons/Fox, Gandy Goose, 2/25/51 – Connie Rasinski, dir.), the color remake of Good Old Irish Tunes (6/27/41). While constituting another of Gandy Goose’s many fanciful dreams, this one is a bit more interesting than most for being fashioned more as a mood piece than a surreal laugh provoker, and benefits from lush atmospheric backgrounds and the invention of symbolic screen emblems and tropes of the Emerald Isle that would set the bar for many future productions from larger rival studios.

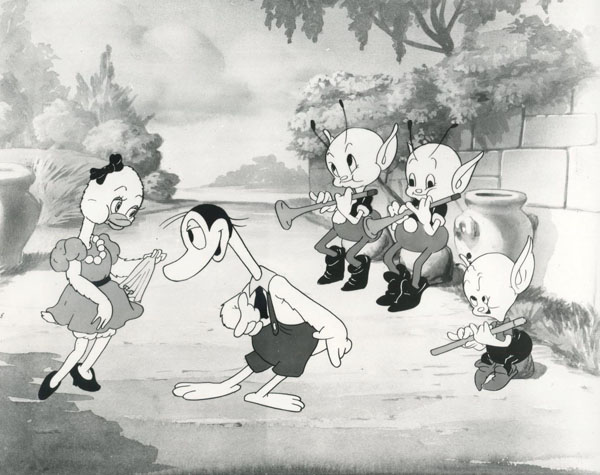

Gandy listens to old records on his phonograph while mopping up around the living room. The musical program begins with “Come Back to Erin”, then segues to an Irish jig. For no apparent reason except to serve as typical Terrytoon-style window dressing, a male and female mouse dance atop the spinning record. A parrot joins in on his perch. Gandy also pantomimes a dance with his mop, bowing to it at the end of the song (only to have the mop handle fall and bop him on the head). Flipping the record over, Gandy falls asleep in a rocking chair to a soprano rendition of “Those Endearing Young Charms” (Bugs Bunny’s old favorite). As his dream begins, Gandy’s chair transforms into a large flying harp, which wafts Gandy over the sea to an Irish castle on Erin soil. He makes a bit of a rough landing, with the harp popping a few strings. Enter a group of wee men from amongst the petals of some nearby flowers. They are not drawn as leprechauns in the traditional green garb and hats, but are designed more like elves, with small antennae, pointed ears, pinkish skin, and red one-piece outfits with little pointed shoes. It appears Rasinski preferred to come up with his own design for these creatures, instead of following any particular model (if any there was at the time) more akin to later traditional cartoon concepts of the characters. Yet, as they have no wings (so are not fairies), this group arguably constitutes cartoons’ first leprechauns. They borrow a feature from the little men who had recently populated a gigantic box-office success from a rival studio (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), in incorporating a comic relief leprechaun shorter and more awkward than the others, roughly paralleling Dopey. While the leprechauns commence a musical accompaniment to Gandy’s dreamy dancing, the little leprechaun constantly tries to join in – but sings off-key so that he is pushed away by the others, and is apparently equally inept at playing the flute, as his companions repeatedly pull the instrument out of his hands before he can blow a note. Gandy meanwhile dances with a “Sweet Irish Rose” – a large flower who transforms into a pretty female goose.

Gandy listens to old records on his phonograph while mopping up around the living room. The musical program begins with “Come Back to Erin”, then segues to an Irish jig. For no apparent reason except to serve as typical Terrytoon-style window dressing, a male and female mouse dance atop the spinning record. A parrot joins in on his perch. Gandy also pantomimes a dance with his mop, bowing to it at the end of the song (only to have the mop handle fall and bop him on the head). Flipping the record over, Gandy falls asleep in a rocking chair to a soprano rendition of “Those Endearing Young Charms” (Bugs Bunny’s old favorite). As his dream begins, Gandy’s chair transforms into a large flying harp, which wafts Gandy over the sea to an Irish castle on Erin soil. He makes a bit of a rough landing, with the harp popping a few strings. Enter a group of wee men from amongst the petals of some nearby flowers. They are not drawn as leprechauns in the traditional green garb and hats, but are designed more like elves, with small antennae, pointed ears, pinkish skin, and red one-piece outfits with little pointed shoes. It appears Rasinski preferred to come up with his own design for these creatures, instead of following any particular model (if any there was at the time) more akin to later traditional cartoon concepts of the characters. Yet, as they have no wings (so are not fairies), this group arguably constitutes cartoons’ first leprechauns. They borrow a feature from the little men who had recently populated a gigantic box-office success from a rival studio (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), in incorporating a comic relief leprechaun shorter and more awkward than the others, roughly paralleling Dopey. While the leprechauns commence a musical accompaniment to Gandy’s dreamy dancing, the little leprechaun constantly tries to join in – but sings off-key so that he is pushed away by the others, and is apparently equally inept at playing the flute, as his companions repeatedly pull the instrument out of his hands before he can blow a note. Gandy meanwhile dances with a “Sweet Irish Rose” – a large flower who transforms into a pretty female goose.

Gandy pursues her down the lane and into a castle, the leprechauns and harp following. Gandy briefly loses her in the castle halls, but she reappears on an upper balcony for a rendition of “Danny Boy”. Gandy floats upon the harp upwards to her, then pulls aside the strings like the gate on an old freight elevator to let the girl step on board and take her back to ground level. There, the leprechauns break into a jig tune, allowing Gandy and the girl to engage in some sprightly dancing. Even the fireplace irons dance with a pair of anthropomorphized flames. The castle’s whole structure rocks and sways to the tune, whose notes attract the attention of a local mountain. The mountain trembles and quakes, and out of its boulders appears a rock giant! (An original of Rasinski’s? Or does this creature have any place in Irish folklore?) Seeming only to want to join in the festivities, the giant nevertheless scares the leprechauns into hiding or running. Gandy and the girl flee also, staying one step ahead of the giant’s huge feet. But Gandy’s dream starts to disintegrate, as the leprechauns disappear, and so does the girl. Gandy leaps off the edge of a cliff, and the playful giant does too – but surreally disappears in mid-air. Gandy lands head-first in a shallow stream at the bottom of the cliff – then the scene transforms back to Gandy’s home, where his head is really in his mopping bucket. Coming to, Gandy says, “Boy, what a dream!”, and is joined by the mice and parrot to sing the last line, “It’s those good old Irish tunes!” (A dead giveaway of the original title of the film in the 1941 version.)

Paramount’s Famous Studios, taking the reins following the undermining of the regime of Max Fleischer, seems to have been at the forefront in spearheading the use of the leprechaun as a starring character. The timing of this move may be somewhat telling as to the studio’s motivations. Despite various varieties of animated ectoplasm appearing on the screen from other studios for well in excess of a decade, Famous had achieved a surprise reaction in 1943 with a one-shot cartoon entitled The Friendly Ghost, featuring a spook named Casper who doesn’t want to scare anybody. While the film didn’t instantly bear progeny, taking a few years to develop into stray follow-ups and ultimately to launch a series, the concept of finding star potential in fanciful beings no doubt hit home with the Paramount writers (and would in fact remain with them even when the rights to Casper were taken away from them in the late 1950’s, leading to the creation of the “substitute” character of Goodie the Gremlin), But it appears that Paramount’s first thoughts of other enchanted creatures to capitalize upon turned to the legends of Ireland’s little men.

Paramount made some effort to do its homework, coming up with both fanciful backdrops and an atmosphere of other enchanted creatures in the surroundings to set the scene for its inaugural episode, The Wee Men (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon. 8/8/47 – Bill Tytla, dir.). Released a few short months before Paramount would re-christen their “follow the bouncing ball” sing-alongs under their original series name “Screen Songs” with The Circus Comes to Clown, this film begins by introducing the number which would become the theme song for all subsequent Screen Songs – “Start the Day With a Song”. (Paramount’s publishing houses had a recurring habit of publishing sheet music for themse from their various cartoons – Does anyone know whether there was sheet music issued for this theme?) Of course, being from Famous Studios, the first gag is a pun – the Emerald Isle depicted as an actual giant emerald jewel. Also, a “moon-kissed blarney stone” receives a real lunar smooch. Misty shores, and a night sky filled with glowing fairies complete the picture, as the camera investigates a small door at the base of a tree. There, we find the home of the leprechauns, busily singing and working at making shoes for the poor. While all the other leprechauns wear white beards, one smaller one still has a short red beard and hair. He helps with the shoemaking by pogo-sticking with a leather “cookie cutter” to stamp out soles from a sheet of leather, and shining shoes on an assembly line with the seat of his pants. A clock strikes midnight, and its calendar mechanism changes the date to March 17. This happens to be the 121st birthday of the young leprechaun, Paddy. Today he is a man. Paddy is presented with his first pipe – but has a bit of trouble figuring out how to light it, setting fire to his beard instead. Paddy also wants the honor of getting to deliver the shoes under the full moon – but first has to be filled in on some leprechaun traditions. He is shown for the first time in the woods the burying place of their ancestral crock o’ gold, and informed that any leprechaun captured is honor-bound to lead the capturer to the crock – so don’t get caught.

Paddy carries a knapsack of shoes to various houses which leave their old shoes on the doorstep. But nearby is the house of an old miser (who squeezes coins so tight, the eagles fly off the coins in pain). The miser is nicely animated in typical Bill Tytla menacing fashion – and no doubt the reason for his assignment to this project. He claims to have the gold of everyone – except the leprechauns. Seeing the full moon, and knowing that is when leprechauns deliver shoes, he put a pair of his own on the doorstep – and slips into Paddy’s knapsack while he is making the shoe swap. Paddy is captured, and promises to lead the miser to the crock. But not without a few detours. Paddy crawls through a log, and the miser follows – but as he comes out the other end, he is being pecked on top of the head by a woodpecker. Paddy crawls between a mule’s legs, while the miser takes a swift kick from trying the same thing. Paddy runs through a swamp, and the miser falls into a patch of deep water. Finally, after nearly running the miser ragged with a final burst of speed, Paddy claims they’re at the spot, and that it’s buried under an old tree stump. The miser claws at the dirt with his bare hands, but Paddy suggests he’ll need a shovel. The miser prepares to go back to his house to fetch one, but leaves his hat and coat on branches protruding from the old stump as a marker, making the leprechaun promise he won’t move the clothes. Back the miser runs retracing his path – and even leaping over the moon just appearing on the horizon. When he returns, he shovels dirt madly – but finds nothing. And no wonder – Paddy has placed identical hats and coats on about 50 identical looking forest stumps. The miser collapses in a dead faint into the hole he just dug, while Paddy plants a lily on his chest. Paddy returns to the laughs and cheers of the other leprechauns – and tumbles down the stairs to land on a large birthday cake they have prepared for him. Amidst the frosting, Paddy discovers his beard on fire again from one of the candles, and the other leprechauns smother it out with slaps of their hands as Paddy sheepishly smiles for the iris out.

Paddy carries a knapsack of shoes to various houses which leave their old shoes on the doorstep. But nearby is the house of an old miser (who squeezes coins so tight, the eagles fly off the coins in pain). The miser is nicely animated in typical Bill Tytla menacing fashion – and no doubt the reason for his assignment to this project. He claims to have the gold of everyone – except the leprechauns. Seeing the full moon, and knowing that is when leprechauns deliver shoes, he put a pair of his own on the doorstep – and slips into Paddy’s knapsack while he is making the shoe swap. Paddy is captured, and promises to lead the miser to the crock. But not without a few detours. Paddy crawls through a log, and the miser follows – but as he comes out the other end, he is being pecked on top of the head by a woodpecker. Paddy crawls between a mule’s legs, while the miser takes a swift kick from trying the same thing. Paddy runs through a swamp, and the miser falls into a patch of deep water. Finally, after nearly running the miser ragged with a final burst of speed, Paddy claims they’re at the spot, and that it’s buried under an old tree stump. The miser claws at the dirt with his bare hands, but Paddy suggests he’ll need a shovel. The miser prepares to go back to his house to fetch one, but leaves his hat and coat on branches protruding from the old stump as a marker, making the leprechaun promise he won’t move the clothes. Back the miser runs retracing his path – and even leaping over the moon just appearing on the horizon. When he returns, he shovels dirt madly – but finds nothing. And no wonder – Paddy has placed identical hats and coats on about 50 identical looking forest stumps. The miser collapses in a dead faint into the hole he just dug, while Paddy plants a lily on his chest. Paddy returns to the laughs and cheers of the other leprechauns – and tumbles down the stairs to land on a large birthday cake they have prepared for him. Amidst the frosting, Paddy discovers his beard on fire again from one of the candles, and the other leprechauns smother it out with slaps of their hands as Paddy sheepishly smiles for the iris out.

The Emerald Isle (Paramount/famous, Screen Song, 2/25/49 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.), is a more plotless Screen Song than usual. Its first two minutes consist of the usual array of visual puns – “The Rocky Road to Dublin” depicted as elevated on the frameworks of rocking chairs; a slice of steak sweeps a counter, announcing that he’s the “Irish Sweepstakes”; etc. The entire clan of leprechauns from “The Wee Men” make a cameo reappearance for about two and a half minutes of the film as an Irish band – mostly playing, with very little in the way of sight gags. A tuba playing leprechaun runs out of wind and substitutes a bicycle pump. Little Paddy performs his flute solo dodging the performance of cymbals and a trombone. And (in a few scenes I should have included in my “Hearts and Flowers” articles, they are accompanied in dance by a chorus line of shamrocks and a “wild Irish rose”. Nothing much else – in fact, they can’t even come up with a closing gag, but just ride out the ending having them finish a chorus of “MacNamara’s Band.”

Leprechaun’s Gold (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon, 10/14/49 – Bill Tutla, dir.) gives the feeling of being a retread of “The Wee Men”, with less action and ideas. The same cast returns, with several introductory shots and many backgrounds reused from the first film. This time, the opening sequence is occupied by a ceremony of “washing their gold” under a full moon. Why it needs washing is never explained – it’s not even buried, but kept in a secret compartment below the floor. The little leprechaun Paddy reaffirms his resemblance to Dopey by a scene in which the wash water sloshes around in his head, directly resembling the washing scene in “Snow White”, and flashing gold coins in his mouth instead of teeth (resembling Dopey’s placing of diamonds in his eyes in the Disney feature). We get a repeat to Paddy of the leprechaun code requiring the gold to be given as a ransom for any leprechaun captured. And, nearly identically to “The Wee Men”, Paddy is sent out for his first venture to collect potatoes left for them on a widow’s doorstep, with the warning to not get caught. This time, however, Paddy encounters the same old miser, but not at his own home. Instead, the miser is foreclosing on the widow, ordering her out by morning if the mortgage cant be paid. Paddy feels sorry for the widow, and gets the idea that the leprechauns’ gold supply would do her good. The widow’s daughter Molly (who looks for all the world like Little Audrey without her hair ribbon) is at a window, and Paddy offers willingly to surrender himself to her capture. But Molly doesn’t believe he’s a leprechaun, calling his story “blarney”.

So Paddy tries a different method – faking that he fell off the window and can’t walk, and needs help to be hobbled home. The Paramount writers can’t resist retreading another gag here, having the waiting leprechauns mistake a passing pig for Paddy (instead of a skunk similarly seen in “The Wee Men”). But Paddy finally returns, assisted by Molly, and Paddy announces that she captured him – then darts inside the leprechauns’ tree, emerging with the crock of gold in a wheelbarrow. The amazed Molly thanks Paddy, and sets off for home to tell mother the good news. The other leprechauns are saddened, but take heart that the gold will go to a good cause. Meanwhile, dawn is breaking, and the miser emerges from his home to set out to complete the foreclosure. En route, he spies Molly and the pot of gold. He confronts her, pulls out the mortgage, and tears it up, announcing that the matter is all settled – but that the price went up to a full pot of gold – and makes off with the pot and wheelbarrow. Molly protests that that’s stealing. Paddy appears from nowhere, and reassures her that everything will be all right, taking her to the window of the miser’s home. He tells her that leprechaun gold never stays with those who steal it. Inside, as the miser runs his hands through the pot’s contents, the coins suddenly transform into a swarm of unidentified but hostile insects, who drive the miser out of his house and away for good; then, the insects return to coins again. The mortgage settled, Molly returns the wheelbarrow and the gold crock to the leprechauns, announcing she won’t need it. And for good measure, Paddy appears from under the coins with a full bag of “spuds” for everyone.

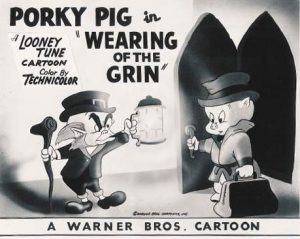

The Wearing of the Grin (Warner, Porky Pig, 7/14/51 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir,), is perhaps the true masterpiece of the genre, and the first to depict leprechauns in a somewhat more sinister fashion. Out scene opens on a stormy night on a spooky mountain road, with a rain-drenched sign reading, “Sure, and it’s still 12 miles to Dublin town”. Traveling salesman Porky Pig realizes he’ll never make it in the storm, and tries a “quaint old castle” as a hopeful prospect for an evening’s lodging. But a foreboding sign on the pathway states, “Beware the leprechauns”. Porky scoffs at the warning as nonsense, and raps at the front door with a shamrock-shaped knocker. When no one answers, he peeps in – and spies a mysterious shadowy figure. But the figure lights a candle, and appears harmless enough, introducing himself as Shamus O’Toole, castle caretaker. Again comes a word of warning, as O’Toole explains the castle has been empty for many years, with not a living thing but – the leprechauns. Porky’s in no mood for this blarney – and insists on being taken to a room, slamming rhe huge front door behind him. The impact of the door closing causes a heavy steel mace to fall from a mounting above the door – directly on Porky’s head, knocking him unconscious. As soon as Porky’s out like a light, a transformation takes place in the old caretaker – who splits in two at the waist. O’Toole – whose’s real name is O’Pat – is only half the height we first saw, and has been standing on the shoulders of another wee man – O’Mike – in one caretaker suit. (The names O’Pat and O’Mike may perhaps be a backhanded reference to the Spencer Tracy/Kathryn Hepburn feature “Pat and Mike” (1952), which was presumably currently in production.) O’Pat is chief of the leprechauns, and while O’Mike worries himself silly that the stranger will find their pot of gold (hidden under O’Mike’s hat), O’Pat insists that he alone with determine how to deal with the likes of this intruder. Returning to their totem-pole positions in the caretaker costume, they revive Porky, and escort him to a room.

The Wearing of the Grin (Warner, Porky Pig, 7/14/51 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir,), is perhaps the true masterpiece of the genre, and the first to depict leprechauns in a somewhat more sinister fashion. Out scene opens on a stormy night on a spooky mountain road, with a rain-drenched sign reading, “Sure, and it’s still 12 miles to Dublin town”. Traveling salesman Porky Pig realizes he’ll never make it in the storm, and tries a “quaint old castle” as a hopeful prospect for an evening’s lodging. But a foreboding sign on the pathway states, “Beware the leprechauns”. Porky scoffs at the warning as nonsense, and raps at the front door with a shamrock-shaped knocker. When no one answers, he peeps in – and spies a mysterious shadowy figure. But the figure lights a candle, and appears harmless enough, introducing himself as Shamus O’Toole, castle caretaker. Again comes a word of warning, as O’Toole explains the castle has been empty for many years, with not a living thing but – the leprechauns. Porky’s in no mood for this blarney – and insists on being taken to a room, slamming rhe huge front door behind him. The impact of the door closing causes a heavy steel mace to fall from a mounting above the door – directly on Porky’s head, knocking him unconscious. As soon as Porky’s out like a light, a transformation takes place in the old caretaker – who splits in two at the waist. O’Toole – whose’s real name is O’Pat – is only half the height we first saw, and has been standing on the shoulders of another wee man – O’Mike – in one caretaker suit. (The names O’Pat and O’Mike may perhaps be a backhanded reference to the Spencer Tracy/Kathryn Hepburn feature “Pat and Mike” (1952), which was presumably currently in production.) O’Pat is chief of the leprechauns, and while O’Mike worries himself silly that the stranger will find their pot of gold (hidden under O’Mike’s hat), O’Pat insists that he alone with determine how to deal with the likes of this intruder. Returning to their totem-pole positions in the caretaker costume, they revive Porky, and escort him to a room.

On the way up, however, O’Pat separates from O’Mike, the former climbing the staircase railing while the latter uses the regular stairs. While the seemingly headless O’Mike takes Porky’s hat and coat, the legless O’Pat enters from the other side of the room, asking if Porky’s seen the other half of him. “It’s right back there, Shamus”, Porky calmly directs him, noting “Some people just can’t keep track of their other halves.” Then comes the wild shock take, as Porky looks again. The two parts of Shamus stand side by side, as the head asks, “Now isn’t this sight enough to set the heart crossways in you?” “L-l-l-l-l-LEPRECHAUNS”, shrieks Porky, and dives under the covers of the bed. It’s a Murphy bed, and folds into the wall, dropping Porky into a hidden tunnel in the wall. Porky falls deep into the dungeons of the castle, landing in a large witness chair beside a judge’s bench. O’Mike appears as bailiff, announcing the case of the Little People v. Porky Pig, for attempting to steal the pot of gold. Judge O’Mike, in powdered wig, takes the bench, and before taking a word of testimony, enters verdict: “Guilty as the day is long.” Porky attempts to protest, but is kept quiet by well placed shillelagh blows from O’Mike. O’Pat sentences Porky to the wearing of the Green Shoes. O’Mike returns with same – emerald green, which O’Mike laces to Porky’s feet. Porky is a bit taken aback, as the shoes look appealing. “I’m afraid I had you fellas all wrong. Why they’re the nicest shoes I ever – – I ever – -“ His voice trails off to an “I – yi – yi – yi -yi – -“ as the shoes begin dancing an Irish jig under their own power, carrying their hapless wearer with them. The two leprechauns howl with laughter, as Porky dances helplessly over a surreal dream-like Irish countryside. He passes a giant crock of gold, from which huge coins fall, nearly flattening him, with faces of the two leprechauns on them still laughing. Porky grabs his ankles and manages to pry the shoes off, throwing them behind him. But the shoes aren’t giving up that easily, and chase him in a hot pursuit. In more surreal imagery, Porky leaps off a landing railed with Irish harps, while the shoes also leap and chase him in mid-air. Porky falls into the mouthpiece of a giant leprechaun pipe, and is blown out the other end as a smoke puff, materializing into himself. He lands on the ground, and runs straight at the camera toward some vertical lines suggesting bars, trying to break through.

On the way up, however, O’Pat separates from O’Mike, the former climbing the staircase railing while the latter uses the regular stairs. While the seemingly headless O’Mike takes Porky’s hat and coat, the legless O’Pat enters from the other side of the room, asking if Porky’s seen the other half of him. “It’s right back there, Shamus”, Porky calmly directs him, noting “Some people just can’t keep track of their other halves.” Then comes the wild shock take, as Porky looks again. The two parts of Shamus stand side by side, as the head asks, “Now isn’t this sight enough to set the heart crossways in you?” “L-l-l-l-l-LEPRECHAUNS”, shrieks Porky, and dives under the covers of the bed. It’s a Murphy bed, and folds into the wall, dropping Porky into a hidden tunnel in the wall. Porky falls deep into the dungeons of the castle, landing in a large witness chair beside a judge’s bench. O’Mike appears as bailiff, announcing the case of the Little People v. Porky Pig, for attempting to steal the pot of gold. Judge O’Mike, in powdered wig, takes the bench, and before taking a word of testimony, enters verdict: “Guilty as the day is long.” Porky attempts to protest, but is kept quiet by well placed shillelagh blows from O’Mike. O’Pat sentences Porky to the wearing of the Green Shoes. O’Mike returns with same – emerald green, which O’Mike laces to Porky’s feet. Porky is a bit taken aback, as the shoes look appealing. “I’m afraid I had you fellas all wrong. Why they’re the nicest shoes I ever – – I ever – -“ His voice trails off to an “I – yi – yi – yi -yi – -“ as the shoes begin dancing an Irish jig under their own power, carrying their hapless wearer with them. The two leprechauns howl with laughter, as Porky dances helplessly over a surreal dream-like Irish countryside. He passes a giant crock of gold, from which huge coins fall, nearly flattening him, with faces of the two leprechauns on them still laughing. Porky grabs his ankles and manages to pry the shoes off, throwing them behind him. But the shoes aren’t giving up that easily, and chase him in a hot pursuit. In more surreal imagery, Porky leaps off a landing railed with Irish harps, while the shoes also leap and chase him in mid-air. Porky falls into the mouthpiece of a giant leprechaun pipe, and is blown out the other end as a smoke puff, materializing into himself. He lands on the ground, and runs straight at the camera toward some vertical lines suggesting bars, trying to break through.

Original background painting from WEARING OF THE GRIN

The camera pulls back to reveal the lines are strings of a giant harp – and the golden harp framework suddenly shrinks around Porky’s hands, trapping them as if in handcuffs. The shoes sneak up behind him, and deliver a swift kick, flipping Porky into the air – and his feet right back into the shoes. With his hands now restrained, Porky can no longer remove the shoes, which dance him off a cliff. He lands in a pot of molten gold, and flounders around – until a dissolve brings us back to reality, and we find Porky back in the main hall of the castle, floundering in a puddle of water Shamus has just dumped on him to revive him. As Porky comes to, one look at Shamus is enough to send him screaming and leaping to the mounts above the hall door from which the mace fell. “L-l-leave me alone, you old leprechauns. I d-d-don’t want your pot of gold!”, he shouts. “Leprechaun, sir? Pot of gold, sir?”, questions Shamus. “D-didn’t you sentence me to wear the green shoes?”, a puzzled Porky asks. “No sir. Why would I be after doing such a daft thing?”, responds Shamus, who asks him to come down so Shamus can find him a soft bed. Porky tells him to never mind, tremulously picks up his baggage, and insists he’s late for an appointment – “w-w-with my psychiatrist!” Porky streaks off over the hills. But was it all a dream? Hardly, as “Shamus” O’Pat reaches down for the extra hand of O’Mike from his trousers, shaking it in a handshake of victory, while the scene irises out to green with a shamrock-shaped iris. (Original title fans’ note: At least one fellow fan of restoring titles on the internet appears to be on to something. The ending of this cartoon in present prints abruptly cuts from the green screen after the iris out to a black screen from which fade in the closing Warner rings. But the rings are not in the right color for the season of this cartoon’s release, and actually come from the year of its Blue Ribbon reissue. The original rings were for a Looney Tune, most likely in orange with black center. So how was the transition handled in the original footage? One restorer suggests that the green background stayed on the screen rather than changing to black, then dissolved to the orange rings. It looks so right, I believe him wholeheartedly. Judging from past studio experience, I believe a similar ending had been planned by Frank Tashlin for the missing footage of The Stupid Cupid, which abounds in irises to red in several transitional shots.)

Spooking With a Brogue (Paramount/Famous, Casper. 5/27/55, Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Having already largely run out of ideas for their leprechaun troupe, the Paramount writers settle for a sort of half-sequel, adapting their theme to the Casper series and retaining the miser. Casper’s having his usual run of rotten luck making friends, saying hi to a sailor but walking through several objects in the process to scare him silly. He sees a travel agency poster about Ireland – the land of friendly people – and ocean-hops to the Emerald Isle (with the usual repeats of the island as a green jewel, and a truly “rocky” road to Dublin). The miser makes his reappearance, foreclosing on a widow and son. The little boy (standard model Billy with a brogue) determines to make things right by catching a leprechaun and claiming his crock of gold. Unfortunately, the boy knows as much about leprechauns as Henery Hawk knows about chickens – and captures Casper instead. Casper can see the kid is a bit off-the-deep-end, but tries to humor him, finding various substitutes for gold. Corn kernels (which the birds eat right out of Billy’s hand). A pot from the bottom of a lake – full of goldfish. A dozen eggs with gold paint – all of which crack into baby chicks. Billy keeps persisting that Casper lead him to the real gold – and passes under the window of the miser. Hearing Billy talk of leprechauns and gold, the miser appears with a sack, and throws it over Casper, carrying him back inside his house and locking Billy out. Inside, the miser dumps Casper out of the sack and also demands the gold. Casper gets up, trying to explain he was only playing leprechaun – and passes right through the miser’s hand. The miser heads for the hills, leaving behind his already large gold stockpile, yelling, “Keep the gold! I don’t want it!” Casper and Billy thus head for Billy’s home, with a wheelbarrow of real gold for the widow, borrowing Chuck Jones’s shamrock-shaped green iris out.

Droopy Leprechaun (MGM, Droopy, 7/4/58 – Michael Lah, dir.), may mark one of the least inspired leprechaun cartoons of the genre – possibly accounting for it being Droopy’s swan song, as his last theatrical appearance until “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” Droopy is a tourist, on a stopover between flights at Dublin. Approximately a minute and a half of the film passes without a laugh, as Droopy uses the time for sightseeing, intending to see Shillelagh Castle, and en route purchasing a souvenir leprechaun hat. Lingering on a street corner is Spike, who upon seeing Droopy pass, jumps to the conclusion that he’s “A real live leprechaun! It’s the first one I’ve ever seen – the first one anybody’s ever seen!” (If this is so, Irishman, then how did the lore get started in the first place?) A travel brochure tells Droopy that Shillelagh Castle is supposed to be haunted by the ghost of the Mad Duke (who is an exact double for Spike in a suit of armor). Of course, Spike follows Droopy to the castle, and hides in just such a suit of armor. Double mistaken identity drives the remainder of the film – Spike convinced that Droopy is a leprechaun – a droopy one at that, even rarer – and Droopy convinced Spike is the Mad Duke. Most gags are cliche (such as Spike using a magnet to attract a metal helmet that has fallen on Droopy – but instead dragging in every other suit of armor in the hallway) or forced in their execution (as in Spike announcing his intention to hide and surprise Droopy as he passes by, but ducking into a clearly spear-studded Iron Maiden and closing it upon himself).

Droopy Leprechaun (MGM, Droopy, 7/4/58 – Michael Lah, dir.), may mark one of the least inspired leprechaun cartoons of the genre – possibly accounting for it being Droopy’s swan song, as his last theatrical appearance until “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” Droopy is a tourist, on a stopover between flights at Dublin. Approximately a minute and a half of the film passes without a laugh, as Droopy uses the time for sightseeing, intending to see Shillelagh Castle, and en route purchasing a souvenir leprechaun hat. Lingering on a street corner is Spike, who upon seeing Droopy pass, jumps to the conclusion that he’s “A real live leprechaun! It’s the first one I’ve ever seen – the first one anybody’s ever seen!” (If this is so, Irishman, then how did the lore get started in the first place?) A travel brochure tells Droopy that Shillelagh Castle is supposed to be haunted by the ghost of the Mad Duke (who is an exact double for Spike in a suit of armor). Of course, Spike follows Droopy to the castle, and hides in just such a suit of armor. Double mistaken identity drives the remainder of the film – Spike convinced that Droopy is a leprechaun – a droopy one at that, even rarer – and Droopy convinced Spike is the Mad Duke. Most gags are cliche (such as Spike using a magnet to attract a metal helmet that has fallen on Droopy – but instead dragging in every other suit of armor in the hallway) or forced in their execution (as in Spike announcing his intention to hide and surprise Droopy as he passes by, but ducking into a clearly spear-studded Iron Maiden and closing it upon himself).

One somewhat more clever gag has Droopy holding Spike at bay at the point of a cannon barrel. Spike tries to sweet talk Droopy into friendship as a fellow kinsman – but Droopy fires anyway, the cannonball burrowing deep in Spike’s belly and bulging out his backside, as Spike comments, “Why the dirty double-crosser.” Spike pins Droopy’s hat to the wall of an open gate with a crossbow shot, but Droopy loosens the slip-knot on the rope holding up the portcullis, which smashes on top of Spike’s head, bounces off, then repeatedly falls and bounces off Spike again and again, driving him into the ground. Droopy catches his flight out in the nick of time, and Spike is left running down the runway, screaming for them to bring back his leprechaun. His commotion attracts the local Paddy Wagon, where he is locked up as a lunatic. Inside the wagon, Spike complains at his own countrymen not believing him, and bemoans having had his fortune in the palm of his hand. But next to him, in an aura of green, is a real leprechaun listening to his story. Spike goes gaga again, claiming that his fortune’s made. But perhaps, Spike is the only one who can perceive things this way, as the Paddy Wagon continues with no loss of speed toward its destination, the sanitarium.

His Better Elf (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker, 5/19/58 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – has been previously written upon in my article, Go To Hades (Pt. 2). In brief re-summary, Woody, in a tumbledown shack and swamped with bills, finds a four leaf clover growing out of the floorboards, which transforms into a leprechaun woodpecker (a miniature green twin to himself, speaking with a brogue). He grants Woody three wishes, and Woody wishes for “Gold, gold, GOLD!”, and finds it at the end of a rainbow, not realizing he’s landed inside a bank vault. The cops are on Woody’s heels, and while the leprechaun intervenes with various pranks including numerous firecrackers, transforming into a lion, and putting a shark as a booby-trap in a small puddle, Woody is captured and cuffed. Woody uses his second wish to get out of the mess, with the leprechaun substituting a skunk in place of Woody in the cuffs. Back at home, Woody uses his final wish on the leprechaun – “GO TO BLAZES!!” The leprechaun descends into Hades, a place where he’s been many times before, receiving a “Welcome back” from the devil.

His Better Elf (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker, 5/19/58 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – has been previously written upon in my article, Go To Hades (Pt. 2). In brief re-summary, Woody, in a tumbledown shack and swamped with bills, finds a four leaf clover growing out of the floorboards, which transforms into a leprechaun woodpecker (a miniature green twin to himself, speaking with a brogue). He grants Woody three wishes, and Woody wishes for “Gold, gold, GOLD!”, and finds it at the end of a rainbow, not realizing he’s landed inside a bank vault. The cops are on Woody’s heels, and while the leprechaun intervenes with various pranks including numerous firecrackers, transforming into a lion, and putting a shark as a booby-trap in a small puddle, Woody is captured and cuffed. Woody uses his second wish to get out of the mess, with the leprechaun substituting a skunk in place of Woody in the cuffs. Back at home, Woody uses his final wish on the leprechaun – “GO TO BLAZES!!” The leprechaun descends into Hades, a place where he’s been many times before, receiving a “Welcome back” from the devil.

Next time: Hanna-Barbera and Paramount “mine” for old gold in the television era, hoping their leprechauns will let them hit the jackpot once again. In the meantime, have a Happy St. Patrick’s Day!

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Famous did put all of its ex-Disney animators to work on “The Wee Men” and at almost 10 minutes, the cartoon’s exceptionally long, even for a 1940s effort before the budget cutting hit, and the results are pretty impressive, as the miser’s animation creates the required menace to justify the longer story. It’s also an example of the shorts the studio periodically tried to do that weren’t straight-out comedies, which was sort of a holdover from the old Fleischer Color Classic days, when they studio tried to mimic the Disney story style.

“Leprechauns’ Gold” manages to be even longer, but was a perfect example of the rut the studio would fall into at the end of the decade, in taking a cartoon that worked, and then simply running that idea into the ground via repetition (they’d do the same thing with the “Land of the Lost Jewels” sequels, let alone the 50s cartoons with the continuing characters). It probably works better if you haven’t seen the first cartoon.

Jones and Maltese liked doing nightmarish dream sequences — “Hypo-Condri-Cat” and “Fresh Airedale” were two previous examples, but the one in “Wearing of the Grin” is the most extended and the best, and since it features Porky, definitely recalls the weirdness of Clampett’s “Porky in Wackyland” — even the backgrounds here look like a sparser version of the ones done for the color remake, “Dough for the Do-Do” (Clampett had used the four-leaf clover iris out earlier, in “We the Animals Squeak”, though it had zero to do with leprechauns — the Korean redrawn actually did color it green, while the computer colorized one just left it black. It may have been one of the few colorizing choices that was better the first time around).

Faith and bejabbers, ’tis a “magically delicious” post ye’ve written, me boyo, to be sure! The blessings of St. Patrick upon ye!

There was a whole genre of jokes in the early 20th century that began with the line: “Two Irishmen, Pat and Mike, were walking along Broadway….” Irishmen were always Pat and Mike, just as Germans were always Hans und Fritz, Poles were always Yash and Stash, and Russians were always Mischa and Grischa.

The appearance of leprechauns varied depending on the region of Ireland, but prior to the 20th century they were normally depicted as wearing red, not green. As for the rock giant, there’s a rock formation in Northern Ireland called the Giant’s Causeway, a vast area of interlocking six-sided basalt pillars. It’s a natural formation, but because of the size of the pillars and the regularity of the hexagonal pattern it was long thought to have been constructed by giants. The Vikings controlled much of Ireland for centuries, and giants of various kinds (e.g., rock, frost, fire) figure prominently in Norse mythology. So Connie Rasinski was right on the money on both counts. Never underestimate the intellectual subtext of early Terrytoons!

Leprechauns may have made an appearance in two lost silent cartoons. One is “Felix the Cat at the Rainbow’s End” (Educational Pictures, 13/12/25 — Pat Sullivan, dir.). What could Felix possibly have found at the rainbow’s end, other than a leprechaun’s pot of gold?

In the lengthy filmography of Mutt and Jeff cartoons, there is an entry titled “Mutt and Jeff in Iceland” (1920). However, I have a very strong suspicion that this is a typo, and that the setting of the cartoon was actually Ireland. Iceland — the most remote, inaccessible, sparsely populated country in Europe — did not even have an airport until the U.S. military built one during WWII; even worse, in 1920 the country, like the U.S., was under Prohibition — and the ban on beer would not be repealed until 1989! Obviously these early cartoons were not meant to be realistic travelogues, but it’s hard to imagine what sort of jokes an Icelandic setting might have inspired; whereas when it comes to Ireland (if the feeble efforts of the Famous gag men are any indication), the jokes pretty much write themselves. Iceland might have served as a generic Arctic setting — except that Mutt and Jeff had already been to “The Frozen North” the previous year (1919), and would return to “The Far North” a year later (1921). Besides, a glance at the titles alone shows that during their adventures in the silent era, the mismatched duo had traveled to Scotland, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Russia, the Balkans, Mexico, Argentina, Egypt, “Darkest” Africa, the Far East, the South Seas, and even Mars and Hell. Are we to believe that their odyssey could somehow have bypassed the Emerald Isle? Saints presarve us!

Of course, we’ll never know for certain unless some intrepid collector, digging through ancient film canisters in some long-forgotten archive, brings these lost films to light — and we’ll all have cause to celebrate if that should ever happen. But I’ll bet you shekels to shamrocks that I’m right.

It should be noted that “Pat and Mike” cross-talk jokes were a staple of stage comedians and magazine cartoons for generations before “Wearing of the Grin” was made, in no small measure because Padraig (paw-rig) and Micheal (mee-hawl) were for a very long time two of the most common names for males in Ireland, owing to a tradition of naming boys for saints.

Fun article, CEG! My brother’s name is Mike and his wife’s name is Pat. Double Ironiy: Neither are Irish (he’s and I am Greek, she’s Hispanic.:O))

A beautiful post, again! Thank YOO! I am amazed thst Famous actually “o.d.’ed” on their leprechaunitis! Lol

No mention of the color swap on “the Red Shoes”?

One can make a case that the elves in “Make Believe Revue” (Columbia/Screen Gems, Color Rhapsodies, 22/3/35 — Ben Harrison, story; no director credited) are actually leprechauns.

A young boy, transported by Mother Goose to the two-component Technicolor world of Make-Believe, takes in a show at the Music Box Theatre. The musicians in the orchestra, and the other members of the audience, are tiny bearded elves wearing red hats and jackets. A series of musical numbers featuring dolls, toy soldiers, and bubbles leads into the grand finale, sung by the elfin chorus: “Come on and mix up all your colors so gay, / And color the dark clouds away!” The elves dip a paintbrush into a large bucket of “Rainbow paint” and spread an arc containing all the colours of the two-component spectrum: red, blue, another shade of red, another shade of blue, black, and white. At the end of this rainbow, glory be, is a pot of gold coins.

Granted, the elves don’t sing with Irish accents, and they don’t wear green because there isn’t any green anywhere in this universe. But if that pot of gold at the end of the rainbow doesn’t prove they’re leprechauns, then I’ll be O’Monkey’s uncle.